Abstract

AIM

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a significant health problem for women. Treatments employing muscle derived stem cells (MDSCs) may be a promising approach to this prevalent, bothersome condition, but these treatments are invasive and require collection of cells from one site for injection into another. It is also unknown whether or not these cells establish themselves and function as muscle cells in the target tissues. Alternatively, low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (Li-ESWT) is non-invasive and has shown positive outcomes in the treatment of multiple musculoskeletal disorders, but the biological effects responsible for clinical success are not yet well understood. The aim of this study is to explore the possibility of employing Li-ESWT for activation of MDSCs in situ and to further elucidate the underlying biological effects and mechanisms of action in urethral muscle.

METHODS

Urethral muscle derived stem cells (uMDSCs) were harvest from Zucker Lean (ZUC-LEAN) (ZUC-Leprfa 186) rats and characterized with flow cytometry. Li-ESWT (0.02mJ/mm2, 3Hz, 200 pulses) and GSK2656157, an inhibitor of PERK pathway, were applied to L6 rat myoblast cells. To assess for myotube formation, we used immunofluorescence staining and western blot analysis in uMDSCs and L6 cells.

RESULTS

The results indicate that uMDSCs could form myotubes. Myotube formation was significantly increased by the Li-ESWT as was the expression of muscle heavy chain (MHC) and myogenic factor 5 (Myf5) in L6 cells in vitro. Li-ESWT activated protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) pathway by increasing the phosphorylation levels of PERK and eukaryotic initiation factor 2a (eIF2α) and by increasing activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4). In addition, GSK2656157, an inhibitor of PERK, effectively inhibited the myotube formation in L6 rat myoblast cells. Furthermore, GSK2656157 also attenuated myotube formation induced by Li-ESWT.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this experiment reveals that rat uMDSCs can be isolated successfully and can form myotubes in vitro. PERK/ATF4 pathway was involved in myotube formation, and L6 rat myoblast cells were activated by Li-ESWT to form myotubes. These findings suggest that PERK/ATF4 pathway is activated by Li-ESWT. This study elucidates one of the biochemical pathways responsible for the clinical improvements seen after Li-ESWT. It is possible that this information will help to establish Li-ESWT as an acceptable treatment modality and may help to further refine the use of Li-ESWT in the clinical practice of medicine.

Keywords: Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave treatment, myogenesis, PERK/ATF4 pathway, urethral muscle derived stem cells

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a significant health problem for women affecting more than 13 million women in the United States and profoundly impacting their quality of life1. UI can be classified into stress UI (SUI), urge UI (UUI) and a mixed form of the two, mixed UI(MUI)2. SUI is the most common type of UI affecting 50–86% of incontinent women either alone or in combination with UUI (36%). Risk factors for female SUI include pregnancy, childbirth, obesity, surgery to the pelvic floor, and aging. The prevalence of SUI increases with age and reaches a maximal level around the age of 50 years3.

Anatomically, the urinary continence control system can be divided into two systems: the urethral sphincteric closure system and the urethral supportive system4. The sphincteric closure system is normally provided by the urethral striated muscles, the urethral smooth muscles, and the vascular elements within the submucosa. Striated muscles are most prominent around the middle urethra and may play a role in sphincteric function for the bulk of the entire urethra5,6. The predominant factor associated with SUI is loss of maximal urethral closure pressure more often than loss of urethral support7. When current therapies such as sling or artificial urinary sphincter fail to cure or improve SUI, the application of regeneration-competent urethral striated muscle cells may be an alternative therapeutic approach.

Skeletal muscle is a form of striated muscle composed of multinucleated contractile muscle cells, also called myofibers. During development, myofibers are formed by fusion of mesoderm progenitors called myoblasts, originating from the satellite cells. Satellite cells, which are referred to by many as muscle stem cells, play an essential role in muscle regeneration and recovery as they have the intrinsic ability to generate a large number of new myofibers8,9. Currently in the literature, there are no reports regarding urethral striated muscle stem cells/satellite cells. Understanding the biological characteristics of urethral striated muscle cell will likely expand understanding of urethral anatomy and enhance options for treatment of SUI.

Major research efforts are now focused on achieving expansion of satellite cells in vitro and in vivo to modulate muscle regeneration. Recent research has suggested the possibility that skeletal muscle is sensitive to physical and physiological stressors, including hypoxia, glucose deprivation, anabolic stimulation, imbalances in calcium homeostasis and exercise which trigger the unfolded protein response (UPR). Therefore, it is possible that the UPR may be involved in modulating skeletal muscle regeneration during physiologically challenging conditions.

Currently, Li-ESWT is utilized to induce neovascularization, improve blood supply, and promote tissue regeneration. Very recently, Zissler et al. reported that Li-ESWT stimulates regeneration of skeletal muscle tissue and accelerates repair processes10. In addition, we previously demonstrated that Li-ESWT can ameliorate SUI by promoting angiogenesis, progenitor cells recruitment, and urethral sphincter regeneration in a rat model of SUI induced by vaginal balloon dilation (submitted separately). However, the exact mechanisms responsible for these biological effects remain unknown. The effect of Li-ESWT on endogenous stem cells has been explored by our team 11 and by other research groups12,13. Defocused low-energy shock wave has been shown to activate adipose tissue-derived stem cells in vitro via multiple signaling pathways12. In our previous study, Li-ESWT enhanced the expression of BDNF through activation of PERK/ATF4 signaling pathway14.

With the purpose to further explore the possibility of utilizing Li-ESWT to stimulate urethral myogenesis and to define mechanisms of action, we isolated and characterized urethral striated muscle stem cells, explored the relationship between PERK/ATF4 pathway and myogenesis in vitro, and defined the specific biological effects of Li-ESWT.

Materials and Methods

Isolation of urethral striated muscle derived stem cells and characterization

Zucker Lean (ZUC-LEAN) (ZUC-Leprfa 186) (ZL) rats were used for isolating uMDSCs. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of University of California, San Francisco. In brief, the entire urethra was harvested and immediately transferred to Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The tissue was treated with enzymatic dissociation (0.2% collagenase II and 0.04 u/mL dispase ) for 90 min, after which non-muscle tissue and the striated muscle were gently separated under a dissection microscope. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70 μm nylon filter (Falcon) and incubated with the following biotinylated antibodies: CD45, CD11b, CD31 and Sca1. Streptavidin beads were then added to the cells together with the following antibodies: alexa647-anti-CD34 and phycoerythrin-anti-α7, after which magnetic depletion of biotin-positive cells was performed. The (CD45−CD11b−CD31−Sca1−) CD34+ integrin-α7+ population was then fractionated twice by flow cytometry. The cells were then cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, 1% ascorbic acid, and cell viability was assessed with LIVE/DEAD® Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kits (Life Technologies, NY, USA). Cells were used in the 5th–10th passage.

Characterizing Cellular Markers of uMDSC With Flow Cytometry and Immunostaining

Cell surface markers associated with the MDSC phenotype, either in the quiescent or activated state, have not been well established although several candidates have been reported. Recent characterization of MDSCs has identified the expression of CD13 and MHC-1 and to a lesser extent CD10 and CD56; also noted is the lack of hematopoietic marker expression, including CD45. Therefore, we checked a series of cellular markers with flow cytometry as we previously reported15, including CD34, Int-7α, CD56, Myf5, pax7, and CD1059,16. In brief, the cells were incubated with primary antibodies described above in 50 μL wash buffer (PBS containing 1% FBS and 0.1% Na3N) for 30 min on ice followed by another incubation with FITC conjugated secondary antibody. The cells were then rinsed twice with wash buffer, fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and analyzed by a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACSVantage SE System, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data was analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Experimental Design

To check the myotube formation, we used uMDSCs from 2 groups. (1) Control group: cells treated with 15% FBS. (2) HS group: cells treated with 2% horse serum (HS). In order to explore the effect of Li-ESWT on myogenesis and the possible mechanism, we used rats L6 cells in 4 groups. (1) Veh group: cells treated with 2%HS induction medium as vehicle control (Veh). (2) Li-ESWT group: cells treated with 2%HS induction medium and Li-ESWT (0.02mJ/mm2, 3Hz, 300 pulses) every 3 days for 2 weeks. (3) GSK group: cells cultured with 2%HS induction medium containing GSK2656157 (final concentration was 100nM/ml). (4) GSK and Li-ESWT group: cells cultured with 2%HS induction medium containing GSK2656157 (100nM) and Li-ESWT (0.02mJ/mm2, 3Hz, 200 pulses) every 3 days for 2 weeks. Li-ESWT was administered to the L6 cells when the cell confluence reached 70–80%. The probe was positioned under the cell culture plate with standard commercial ultrasound gel applied between plate and probe. The GSK2656157 was purchased from Vibrant Pharma (Cat No VPI-COA-610) and stored in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). All experiments were repeated in triplicate on cells from each subject, and all data were presented as the average of three independent experiments.

Myogenesis Assay and Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining

With stimulation from trigger factors, myoblast cells differentiate into myocytes then the myotube forms from the fusion of myocytes. This biological process is termed myogenesis. To study myogenesis in vitro, the cells were seeded into six-well plate until 70–80% confluence in DMEM with 10% FBS and antibiotics. In the Li-ESWT and GSK+Li-ESWT groups, cells were treated with Li-ESWT every 3 days with or without GSK in the medium for 2 weeks. We used IF staining to check for myotube formation in the L6 cells after treatment. The cells were fixed with ice-cold methanol for 8 minutes, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 for 5 minutes, and blocked with 5% normal HS in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Next, they were incubated with goat anti-MHC antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After washing with PBS three times, the cells were incubated with DexRed-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, the cells were stained with 4′,6- diamidino-2-phenylindole (for nuclear staining) for 5 minutes. Finally, the IF slides were examined under a fluorescence microscope and photographed.

Protein Isolation and Western Blot Analysis

The cellular protein samples were prepared by homogenization of cells in a lysis buffer containing 1% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium docecyl sulfate, aprotinin (10 mg/mL), leupeptin (10 mg/ mL), and PBS. Cell lysates containing 20 ug of protein were electrophoresed in sodium docecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore Corp, Bedford, MA, USA). The membrane was stained with Ponceau S to verify the integrity of the transferred proteins and to monitor the unbiased transfer of all protein samples. Detection of target proteins on the membranes was performed with an electrochemiluminescence kit (Amersham Life Sciences Inc, Arlington Heights, IL, USA) with the use of primary antibodies for MHC, myf5, p-elf2a, and elf2a (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), p-PERK, and PERK (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), ATF4 and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). After the hybridization of secondary antibodies, the resulting images were analyzed with ChemiImager 4000 (Alpha Innotech) to determine the integrated density value of each protein band.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed according to the Primer of Biostatistics, 5th edition (Glantz SA, McGraw-Hill, Inc, New York, NY, USA). Data were expressed as means standard deviation. Analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by paired T-test was used to determine differences between groups. Statistical significance was set at P≤0.05.

Results

1. Characterization of uMDSCs and myotube formation from uMDSCs

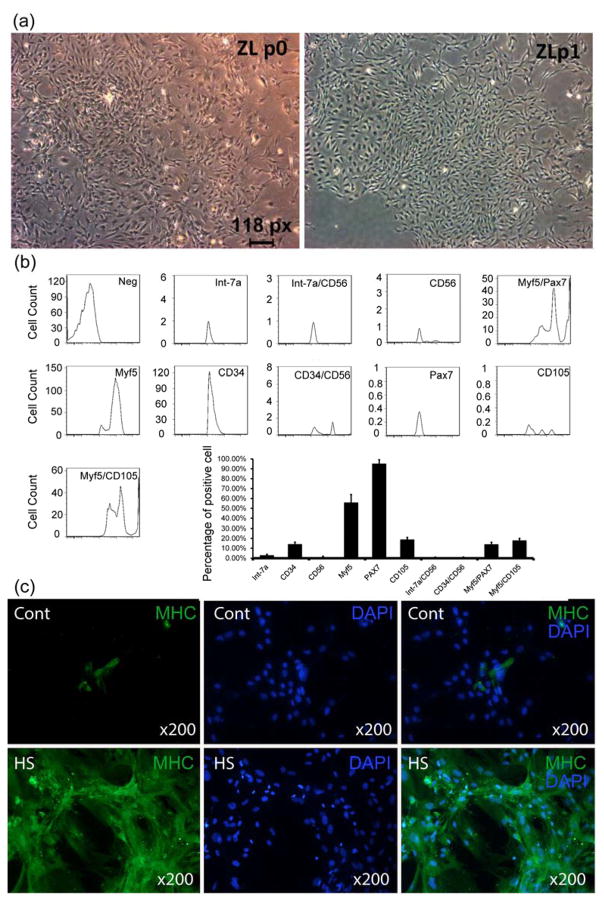

Freshly isolated uMDSCs were of insufficient number and thus required expansion through one passage (P1) of culturing (Fig. 1a). To ensure consistency, a small portion of each P1 cell preparation was examined by flow cytometry. The results indicated the expression of cell surface antigens in a pattern (Fig. 1b) similar to most previous studies. The results showed that CD34 was expressed in 14.2% of cells, Int-7α 0.029%, CD56 0.03%, Myf5 56.65%, pax7 95.3%, CD105 13.4%, Int-7α/CD56 0%, CD34/CD56 0.137%, Myf5/pax7 14.5%, and Myf5/CD105 18.3%.

Figure 1. Characterization of uMDSCs and myotube formation.

(a) Image of uMDSCs from P0 to P1 under microscope. (b) Flow cytometry analysis of uMDSCs surface markers revealed expression of CD34, Int-7α, CD56, Myf5, pax7, CD105, Int-7α/CD56, CD34/CD56, Myf5/pax7, and myf5/CD105. (c) Two groups of uMDSCs were immunostained using MHC for myotube formation. (cont=control, HS=2% horse serum)

In medium supplemented with 15% FBS, few myotubes formed from uMDSCs. However, in medium containing 2% horse serum (induction medium), large numbers of myotubes staining positive for MHC were noted (Fig. 1c).

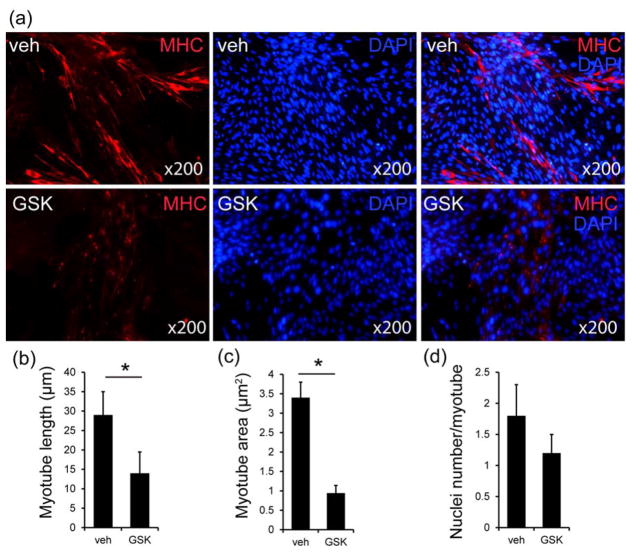

2. Myotube formation was inhibited by GSK2656157 in L6 rat myoblast cells

In medium supplemented with 15% FBS, the L6 cells propagated without differentiation or myotube formation. In medium containing 2% HS (induction medium), the L6 cells formed myotubes staining positive for MHC and myogenin (Fig. 2). The results revealed that the L6 cells could form a certain number of myotubes in vitro in the induction medium (Fig. 2). GSK2656157, a known PERK inhibitor, significantly reduced the formation of myotubes from L6 cells. The length of the myotube of each group was measured, and quantitative analysis showed that myotube length of the GSK2656157 group was significantly shorter than Veh group (p<0.05, Figure 2b). An analysis of the myotube area showed that the area of the myotube was smaller in the GSK2656157 treated L6 cells (p<0.05, Figure 2c). Nuclei were counted in each myotube; we found that the Veh group contained almost the same nuclei per myotube compared to GSK2656157 group (Figure 2d).

Figure 2. Myotube formation was inhibited by GSK2656157 in L6 cells.

(a) Two groups of L6 cells were immunostained using an anti-muscle heavy chain (MHC) antibody and secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (b) Average myotube length. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 300 myotubes in each group (*p<0.05). (C) The average myotube area. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 300 myotubes in each group (*p<0.05). (d) The average number of nuclei per myotube. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 100 myotubes in each group. (Veh=vehicle, GSK=GSK2656157)

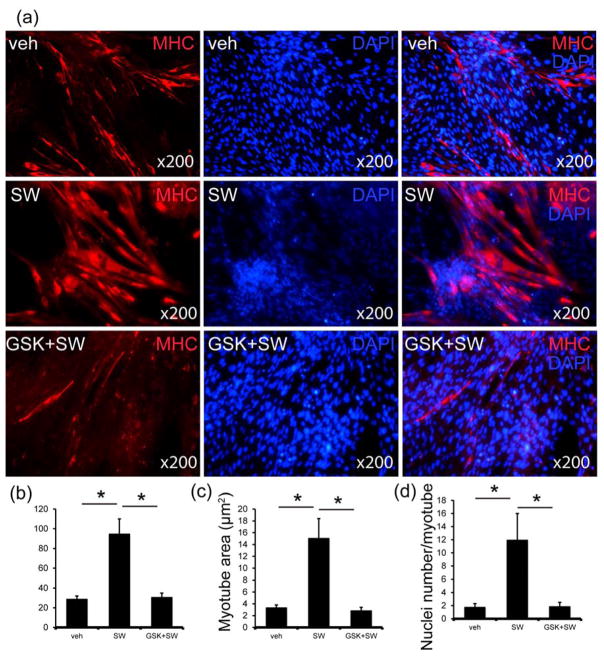

3. Li-ESWT promotes in vitro myotube formation from L6 rat myoblasts, and this could be attenuated by GSK2656157

To test our hypothesis that Li-ESWT can induce muscle regeneration, we examined the effect of Li-ESWT on rat myotube formation in vitro. Compared to induction medium- induced myotube formation, Li-ESWT-induced myotubes grew larger (Fig. 3a). The L6 rat myoblast cells which were treated by Li-ESWT (0.02 mJ/mm2, 200 pulses at 3 Hz) every 3 days for 2 weeks expressed more MHC protein and formed more myotubes. These myotubes were denser, wider, and longer than the myotubes formed with induction medium only (Fig. 3). Interestingly, this effect could be inhibited by GSK2656157 (100nM). The myotubes were fewer, slimmer, and shorter compared with those in the Li-ESWT group. Quantitative analysis showed that myotube length in the Li-ESWT group was significantly longer than in all other groups (p<0.05, Fig. 3b). An analysis of the myotube area showed that the area of the myotube was also bigger in the Li-ESWT group (p<0.05, Figure 3c). Nuclei were counted in each myotube; Li-ESWT groups contained more nuclei per myotube than the other groups (p<0.05, Fig. 3d).

Figure 3. Li-ESWT promotes myogenesis in vitro.

(a) Three groups of L6 Cells (Veh, SW and GSK+SW) were immunostained using an anti-muscle heavy chain (MHC) antibody and secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 (red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). (b) Average myotube length. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 300 myotubes in each group (*p<0.05). (C) The average myotube area. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 300 myotubes in each group (*p<0.05). (d) The average number of nuclei per myotube. The values are the means ± standard deviation for 100 myotubes in each group (*p<0.05). (Veh=vehicle, SW=Li-ESWT, GSK+SW= GSK2656157+Li-ESWT)

Western blot results showed that MHC and Myf5 proteins were significantly enhanced in the Li-ESWT groups (*p<0.05) compared the vehicle group. This effect could be attenuated by GSK2656157 in both GSK and GSK/SW groups (Fig. 4) (*P<0.05). This data indicates that PERK signaling could be responsible for the Li-ESWT induced formation of myotubes in L6 cells.

Figure 4. Li-ESWT increased the expression of MHC and Myf5 in L6 cells, and this response was attenuated by GSK2656157.

(a) Expression of MHC and Myf5 with usage of Li-ESWT and GSK2656157 (n=3 in triplicates). (b) The expression level of MHC increased significantly with Li-ESWT and could be blocked by GSK2656157 (*p<0.05). Intensity ratios depicted in corresponding bar graphs were calculated using MHC and β-actin expression and normalized to the untreated controls. (c) The expression level of Myf5 increased significantly with Li-ESWT and could be blocked by GSK2656157 (*p<0.05). Intensity ratios depicted in corresponding bar graphs were calculated using Myf5 and β-actin expression and normalized to the untreated controls.

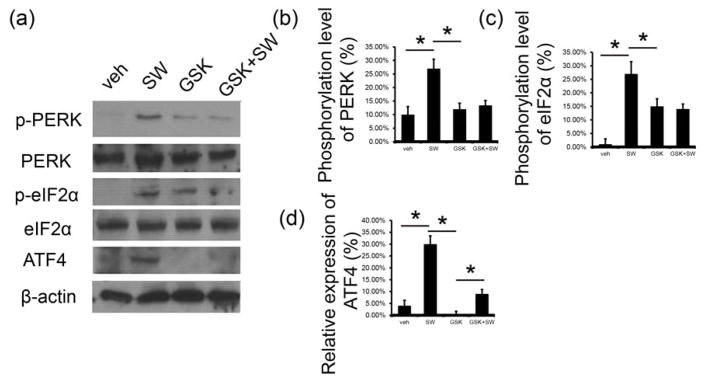

4. Li-ESWT promotes myogenesis through PERK signaling pathway in vitro

As noted above, in vitro myogenesis induced by Li-ESWT could be attenuated by PERK inhibitor GSK2656157. The PERK pathway was evaluated in following experiment. In this study, phosphorylation level of p-PERK, p-eIF2a, and expression of ATF4 were significantly elevated by Li-ESWT (p<0.05, Fig. 5a). GSK2656157, a known PERK inhibitor, was used, and it was found that phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2a were attenuated sharply in both GSK and GSK/SW group, as well as expression level of ATF4 (p<0.05, Fig. 5a, b, c, d).

Figure 5. Li-ESWT activated PERK/ATF4 pathway in L6 cells in vitro.

(a) Expression of p-PERK, PERK, p-eIF2α, eIF2α, and ATF4 with usage of Li-ESWT and GSK2656157 (n=3 in triplicates). (b) The phosphorylation level of PERK increased significantly with Li-ESWT and could be blocked by GSK2656157 (*p<0.05). Intensity ratios depicted in corresponding bar graphs were calculated using phosphorylated (p-) and total protein expression and normalized to the untreated controls. (c) Phosphorylation level of eIF2α increased significantly with Li-ESWT and could be blocked by GSK2656157 (*p<0.05). Intensity ratios depicted in corresponding bar graphs were calculated using phosphorylated (p-) and total protein expression and normalized to the untreated controls. (d) Expression of ATF4 increased significantly with Li-ESWT and could be blocked by GSK2656157 (*p<0.05). Intensity ratios depicted in corresponding bar graphs were calculated using ATF4 and β-actin expression and normalized to the untreated controls.

Discussion

MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of cells that actively produce two populations of cells: a population of cells for immediate muscle repair and a quiescent population for future muscle repair. The satellite cells reside between the basal lamina and the plasma membrane of skeletal muscle fibers. Most previous studies have shown that MDSCs can be isolated from hind limb17. There is no previous report about the urethral striated muscle stem cells. In this study, the MDSCs were harvested from the rat urethra.

Satellite cells are capable of self-renewal and of generating muscle; however, they are considered to be committed to the myogenic lineage16. Satellite cells exhibit a quiescent state and an activated proliferative state during skeletal muscle turnover. Each state can be identified with specific stage markers. Both quiescent and activated satellite cells express a stem cell-specific transcriptional factor, Pax718. Pax7 is regarded as a signal of MDSCs’ commitment to the myogenic lineage because Pax7 knockout mice completely lack satellite cells but contain a normal size population of MDSCs19. Quiescent satellite cells are Pax7-positive but are negative for myogenic Myf5 and MyoD. In contrast, activated satellite cells co-express Myf5 and MyoD together with Pax720. In our first experiment, Pax7 expression was relatively high (95.3%) in uMDSCs according to the flow cytometry, while the expression of Myf5 was 56.65%, which meant that most satellite cells were activated cells. In our subsequent study, the uMDSCs treated with 2% horse serum induction medium formed many myotubes (Fig. 1). In our pilot studies, we have noted that the L6 cells (immortalized rat skeletal myoblast cells) which can be purchased from commercial sources, also form myotubes, therefore, in our next experiments we utilized L6 cells.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) responds to the burden of unfolded proteins by activating intracellular signal transduction pathways, collectively called them Unfolded Protein Response (UPR). Together, at least three mechanistic branches of the UPR regulate the expression of the numerous genes that maintain homeostasis in the ER or induce apoptosis. These are activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6), inositol requiring protein-1 (IRE1), and protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK) 21. PERK is an important branch that is responsible for the attenuation of the overload of misfolded proteins, therefore alleviating ER stress. Recent research has suggested the possibility that skeletal muscle is sensitive to the physiological stressors that trigger the UPR. ER stress and UPR signaling might play roles in myogenesis. It has been demonstrated that high-intensity exercise training resulted in increased mitochondrial biogenesis and low level of ATF4 in the skeletal muscle tissue of rats22. In our current study, we checked the effect of PERK/ATF4 pathway in myotube formation. We applied PERK inhibitor GSK2656157 to interfere with PERK/ATF4 pathway during the myogenesis, and the results demonstrated that myogenesis of L6 cells was inhibited significantly. These data indicate that the PERK/ATF4 pathway participates in the formation of myotubes and thus myogenesis.

ESWT has been utilized in medicine for approximately 40 years 23. Currently, Li-ESWT is prominently used as a therapeutic modality for treatment of musculoskeletal disorders24, erectile dysfunction 25 and certain muscular degeneration issue, such as muscle atrophy of limbs and even acute myocardial ischemia. The proposed mechanism of Li-ESWT in muscle regeneration is to induce neovascularization, improve blood supply and activate the biological factors related to angiogenesis, such as endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). This neovascularization is proposed to increase cell proliferation and eventually induce tissue regeneration. Recently, Zissler, et al. reported that ESWT could accelerate muscle regeneration after acute skeletal muscle injury10. It has been demonstrated that Li-ESWT significantly increased the number of pax7-positive satellite cells and enhanced the expression of myoD and myogenin. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms of ESWT still remain largely unclear. In our study, we applied Li-ESWT to treat L6 rat myoblast cells. We found that Li-ESWT induced myotubes grew larger (Fig. 3). The myotube length in the Li-ESWT group was significantly longer than vehicle group, and the myotube area in the Li-ESWT group was bigger. Moreover, we found that the myotubes in the Li-ESWT groups contained more nuclei per myotube than in the vehicle group. These data suggest that satellite cell myogenic differentiation was a possible mechanism for Li-ESWT therapeutic effects. Li-ESWT could stimulate L6 cells to express more MHC and Myf5 proteins. The increase of MHC and Myf5 implied that L6 cells began to differentiate from myoblast to myocyte. More myocytes contribute to the formation of the myotube as a sequence (Fig. 3). In contrast, the expression of MHC and Myf5 were attenuated sharply by PERK pathway inhibitor, which implies that PERK/ATF4 might be responsible for this biological effect.

To further elucidate the cellular and molecular changes after Li-ESWT and to clarify the mechanisms of Li-ESWT-induced muscle regeneration, we assessed the effect of Li-ESWT on PERK/ATF4 pathway, one branch of the UPR. We found that Li-ESWT increased the phosphorylation level of PERK, eIF2a, and enhanced ATF4 expression. In addition, western blot results confirmed that GSK2656157 effectively attenuated the effect of Li-ESWT on the phosphorylation of PERK, eIF2a, and downstream ATF4 expression.

Conclusion

Striated muscle derived stem cells could be isolated from urethra successfully and could form myotubes. The PERK/ATF4 pathway was involved in the myotube formation. Myogenesis of L6 rat myoblast cells could be activated by Li-ESWT, and activation of the PERK/ATF4 pathway appears to be the underlying mechanism of action of Li-ESWT.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIDDK of the National Institutes of Health under award number R56DK105097 and 1R01DK105097.

References

- 1.Melville JL, Katon W, Delaney K, et al. Urinary incontinence in US women: a population-based study. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165:537–42. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demaagd GA, Davenport TC. Management of urinary incontinence. P T. 2012;37:345–61H. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fritel X, Ringa V, Quiboeuf E, et al. Female urinary incontinence, from pregnancy to menopause: a review of epidemiological and pathophysiological findings. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2012;91:901–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashton-Miller JA, Howard D, DeLancey JO. The functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor and stress continence control system. Scandinavian journal of urology and nephrology Supplementum. 2001:1–7. doi: 10.1080/003655901750174773. discussion 106–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lim SH, Wang TJ, Tseng GF, et al. The distribution of muscles fibers and their types in the female rat urethra: cytoarchitecture and three-dimensional reconstruction. Anatomical record. 2013;296:1640–9. doi: 10.1002/ar.22740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang L, Lin G, Lee YC, et al. Transgenic animal model for studying the mechanism of obesity-associated stress urinary incontinence. BJU international. 2017;119:317–24. doi: 10.1111/bju.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeLancey JO, Trowbridge ER, Miller JM, et al. Stress urinary incontinence: relative importance of urethral support and urethral closure pressure. J Urol. 2008;179:2286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.098. discussion 90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charge SB, Rudnicki MA. Cellular and molecular regulation of muscle regeneration. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:209–38. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deasy BM, Jankowski RJ, Huard J. Muscle-derived stem cells: characterization and potential for cell-mediated therapy. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:924–33. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.2001.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zissler A, Steinbacher P, Zimmermann R, et al. Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Accelerates Regeneration After Acute Skeletal Muscle Injury. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0363546516668622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin G, Reed-Maldonado AB, Wang B, et al. In Situ Activation of Penile Progenitor Cells With Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu LN, Zhao Y, Wang MW, et al. Defocused low-energy shock wave activates adipose tissue-derived stem cells in vitro via multiple signaling pathways. Cytotherapy. 2016;18:1503–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rohringer S, Holnthoner W, Hackl M, et al. Molecular and Cellular Effects of In Vitro Shockwave Treatment on Lymphatic Endothelial Cells. Plos One. 2014:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang B, Ning H, Reed-Maldonado AB, et al. Low-Intensity Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Enhances Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Expression through PERK/ATF4 Signaling Pathway. International journal of molecular sciences. 2017:18. doi: 10.3390/ijms18020433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin G, Garcia M, Ning H, et al. Defining Stem and Progenitor Cells within Adipose Tissue. Stem cells and development. 2008;17:1053–63. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X, Wang S, Chen B, et al. Muscle-derived stem cells: isolation, characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;340:549–67. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0978-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovanecz I, Vernet D, Masouminia M, et al. Implanted Muscle-Derived Stem Cells Ameliorate Erectile Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes, but Their Repair Capacity Is Impaired by Their Prior Exposure to the Diabetic Milieu. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2016;13:786–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urish K, Kanda Y, Huard J. Initial failure in myoblast transplantation therapy has led the way toward the isolation of muscle stem cells: Potential for tissue regeneration. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;68:263. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)68009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zammit P, Beauchamp J. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: stem cell or son of stem cell? Differentiation; research in biological diversity. 2001;68:193–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujimaki S, Hidaka R, Asashima M, et al. Wnt protein-mediated satellite cell conversion in adult and aged mice following voluntary wheel running. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7399–412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.539247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim K, Kim YH, Lee SH, et al. Effect of Exercise Intensity on Unfolded Protein Response in Skeletal Muscle of Rat. Korean J Physiol Pha. 2014;18:211–6. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2014.18.3.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haupt G. Use of extracorporeal shock waves in the treatment of pseudarthrosis, tendinopathy and other orthopedic diseases. J Urol. 1997;158:4–11. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199707000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ioppolo F, Rompe JD, Furia JP, et al. Clinical application of shock wave therapy (SWT) in musculoskeletal disorders. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;50:217–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H, Matheu MP, Sun F, et al. Low-energy Shock Wave Therapy Ameliorates Erectile Dysfunction in a Pelvic Neurovascular Injuries Rat Model. The journal of sexual medicine. 2016;13:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]