Abstract

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) was significantly up-regulated in colorectal cancer (CRC), while the potential relevance to radiation resistance of this phenomenon is still elusive. Relative expressions of target genes were quantified by real-time PCR. The protein level was determined by Western blot. The regulatory effect of miR-149 on WFDC2 (gene encoding HE4 protein) expression was analyzed by luciferase reporter assay. The response to radiation was evaluated by clonogenic assay in vitro and xenograft growth in vivo. WFDC2 was aberrantly up-regulated and miR-149 was down-regulated in CRC. MiR-149 repressed WFDC2 expression via directly targeting its 3’UTR region. The ectopic expression of miR-149 significantly sensitized CRC to radiation both in vitro and in vivo. Likewise, we further demonstrated that WFDC2-deficiency remarkably improved the radiation resistance in CRC. Simultaneously, WFDC2 rescue completely abolished the radiation sensitivity imposed by miR-149. Our data suggested that miR-149 sensitized CRC to radiation via directly inhibiting WFDC2/HE4, which would hold great promise for future therapeutic exploitations.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, miR-149, WFDC2, radiation resistance, xenograft

Introduction

Colorectal cancer situates as the third most common malignancy worldwide and accounts for about 10% of all cases [1]. It’s estimated that 1.4 million new cases have been diagnosed and 694,000 deaths were claimed by CRC in 2012 [2]. The risk factors identified to be associated with CRC so far include old age, obesity, lack of physical exercises, unhealthy lifestyle such as diet and smoking, and underlying genetic disorders [3]. The inflammatory bowel diseases have been increasingly recognized as causal factors in tumorigenesis of CRC [4]. The diagnosis of CRC is usually performed by biopsy of colon during a sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, which is frequently followed by medical imaging to evaluate the malignant degree [3]. The population-based screening is effective in prevention and reducing the CRC-related mortality [5]. Currently, the clinical treatments for colorectal cancer include the combination of surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy [6]. The outcome of CRC may be greatly improved by appropriate therapeutics based on the individual pathological and health conditions.

Radiation therapy is widely applied clinically to treat a variety of human cancers and is one of the beneficial remedy for the comprehensive therapy of CRC [7]. However, the therapeutic effect of individual radiation is greatly limited in clinical practice of CRC due to the hypersensitivity of the normal colon to radiation, which imposes strict requirement on the radiation dose and duration to mitigate the severe injury to normal tissues, which compromises the efficacy of radiotherapy [8]. Despite of numerous academic endeavors invested into exploitations of novel strategies to alleviate the side effects and to improve the sensitivity of CRC to radiation, until now the clinical efficacy is still unsatisfactory [9,10].

The WFDC2 gene encodes a protein called HE4 (human epididymis protein 4), which belongs to the WFDC domain family and features the WAP signature motif consisting of eight cysteine-formed disulfide bonds [11]. HE4 is physiologically secreted into the blood where it functions as a protease inhibitor potentially involved in sperm maturation [12]. Recently, a number of studies demonstrated that HE4 was up-regulated in a variety of human cancers. Most notably, Kemal et al. reported that HE4 was significantly positive in advanced CRC patients and corelated with relative content of carbohydrate antigen 19-9, the most common biomarker for CRC [13]. However, the potential relevance of high HE4 in CRC with radiation resistance has not been addressed yet, which prompted us to clarify this possibility.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-coding RNAs with an average length of 22 nucleotides and exist in a wide range of organisms [14]. MiRs have been characterized with diverse physiological functions through post-transcriptional regulation of mRNAs. Accumulative evidences suggested miRs are involved in an array of human diseases such as heart diseas, kidney disease, nervous disease, obesity and especially cancer [15]. MiR-149 has recently been identified as a tumor suppressor gene, which is susceptible to methylation regulation and has potential therapeutic and prognostic value in CRCs [16-18]. However, whether miR-149 is involved in radiation resistance of CRC is still to be elucidated. Therefore, here we set out to investigate the radiotherapy resistance of CRC along this direction both in vitro and in vivo and attempted to understand the underlying molecular mechanism.

Materials and methods

Patient samples

A total of 16 CRC tumor samples with corresponding adjacent benign tissues were collected from The First Hospital of Quanzhou Affiliated to Fujian Medical University. The protocol for human research was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Quanzhou Affiliated to Fujian Medical University. The written informed consents were obtained from all the patients involved in the donation.

Cell culture

CCD-18Co, HT29 and SW948 cells were obtained and authenticated by the America Type Culture Collection (ATCC, USA). The immortalized CCD-18Co cell was employed as normal control in this study. All cells were maintained in PRMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, USA) and 1% PSG (penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine, Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). The cells were cultured in 37°C incubator with 5% CO2.

qRT-PCR

The relative expression of transcripts was determined by q-PCR using the commercial PowerUp SYBRTM Green Master Mix (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) in according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, the total RNA was extracted from the indicated cells with Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The quality and quantity of RNA samples were determined by BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). 1 μg total RNA was reversely transcribed using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis SuperMix (ThermoFisher, USA) following the manufacturer’s guide. The real-time PCR was performed with the PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mixs (ThermoFisher, USA) in according to the provider’s instruction. The relative expression was calculated using the 2-ΔΔCt method and normalized to GAPDH. The primers were listed as below: WFDC2-Forward: 5’-GCTGGCCTCCTACTAGGGTT-3’; WFDC2-Reverse: 5’-AACACACAGTCCGTAATTGGTT-3’; GAPDH-Forward: 5’-GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT-3’; GAPDH-Reverse: 5’-GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG-3’.

MicroRNA assays

MystiCq microRNA assay (MIRAP00193; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to measure expression of miR-149-3p, normalized against RNU6 control microRNA assay (MIRCP00001; Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The Mission miRNA lentiviral mimic for miR-149-3p (HLMIR0241; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and negative control (NCLMIR001; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were packaged for transduction to create stable cell lines.

Western blot

The cell lysates were prepared in RIPA lysis buffer and protein concentration was determined by the BCA Protein System Kit. The equal amount of protein was resolved by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred onto PVDF membrane on ice. The membrane was briefly blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST buffer and subjected to primary antibody (anti-HE4, Abcam, ab24480, 1:1,000; anti-β-actin, Abcam, ab8226, 1:1,000) hybridization at 4°C overnight. After rigorous wash with TBST for 5 min by 6 times, the PVDF membrane was incubated with secondary antibody (anti-mouse, Abcam, ab6789, 1:5,000; anti-rabbit, Abcam, ab6721, 1:5,000) at room temperature for one hour. The bands were visualized using the Enhanced Chemiluminescence kit (ECL, Millipore, USA) as instructed by the manufacturer.

Luciferase reporter assay

Either wild-type or putative seed region-mutated 3’UTR of WFDC2 was cloned into pGL-3 luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) by double-digestion method. The indicated reporter plasmid was transfected into either scramble or miR-149 expressed stable cell line and allowed for 48 h consecutive culture. Relative luciferase activity was measured with Bright-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

Xenograft mouse model

The immunodeficiency NPG mice of 4~6 weeks old were purchased from Vitalstar, China and housed in the pathogen-free environment for acclimatization for one week. All the animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The First Hospital of Quanzhou Affiliated to Fujian Medical University. The indicated single-cell suspension (106 cells/100 μL) was prepared and mixed with equal volume of Basement Membrane Extracts (R&D System, USA) on ice. The mixture was cautiously subcutaneously inoculated into both lower flanks to establish xenograft tumor. Tumor diameters are measured with digital calipers, and the tumor volume was calculated by the formula: Volume (mm3) = (width)2 × length/2.

Irradiation (IR)

The 500 indicated cells were seeded into 60-mm petri dishes and allowed for attachment for 4 h, which were then radiated with different dosage (0, 5 and 10 Gy) with a 210 kV X-ray source at 2.16 Gy/min (RS-2000 Biological irradiator, Rad Source Technologies, USA). The cells were cultured in 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator for 14 days, and survived colonies were visualized by crystal violet staining and the survival fractions (SF) were calculated. CRC cells stably expressing negative control or miR-149-3p mimic were inoculated into 10 mice in each experimental group on day 0, followed by 10 Gy of irradiation treatment on day 15 and 20 after inoculation. The xenograft tumor growth was monitored as described before.

shRNA knockdown and overexpression of WFDC2 mRNA

The exponentially growing cells were seeded into 6-well plate and infected with lentivirus packaged either WFDC2 shRNA or cDNA. After 24 h, the cells were transferred to 100 mm petri dish for resistance selection. The knockdown or overexpression efficiency was validated by both real-time PCR and western blotting.

Statistical analysis

All results presented in this study were acquired from at least three independent experiments. The data analysis was performed with SPSS 23.0 software, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Turkey’s multiple comparisons test was employed for statistical comparison. The statistical significance was calculated as p value, and P<0.05 was considered as significantly different.

Results

Upregulation of WFDC2 and downregulation of miR-149-3p in CRC

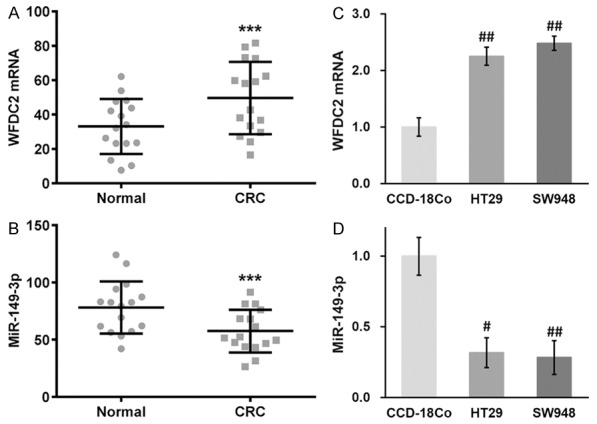

Here we first set out to determine the expressions of both WFDC2 and miR-149 in colorectal cancer in vivo and in vitro. Our results obtained from real-time PCR unambiguously demonstrated that WFDC2 transcripts were significantly increased in CRC patient samples (Figure 1A). In sharp contrast, the expression of miR-149 was dramatically suppressed in CRC in comparison with adjacent benign samples (Figure 1B), which implicated the potential regulatory role of miR-149 on WFDC2 transcripts. Next, we sought to examine the relative expression of WFDC2 and miR-149 in the CRC cell lines. Consistent with our in vivo data, we confirmed the high expression of WFDC2 and low level of miR-149 in HT29 and SW948 CRC cell lines in comparison to the immortalized normal colon cell line CCD-18Co (Figure 1C, 1D). Therefore, we employed these two cell lines for our further investigation with respect to the expression profile of WFDC2 and miR-149.

Figure 1.

Expression profiles of WFDC2 mRNA and miR-149-3p in CRC patient tissues and cell lines. (A, B) Expressions of WFDC2 mRNA (A) and miR-149-3p (B) were examined in CRC patient tumor samples and adjacent normal tissues. (C, D) Expressions of WFDC2 mRNA (C) and miR-149-3p (D) were examined in human normal colon cell line CCD-18Co, as well as human CRC cell lines HT29 and SW948. Values are mean ± SD. ***P<0.001 compared to normal tissues. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 compared to CCD-18Co.

MiR-149-3p directly recognizes the 3’-UTR of WFDC2 mRNA and inhibits its protein expression in CRC cells

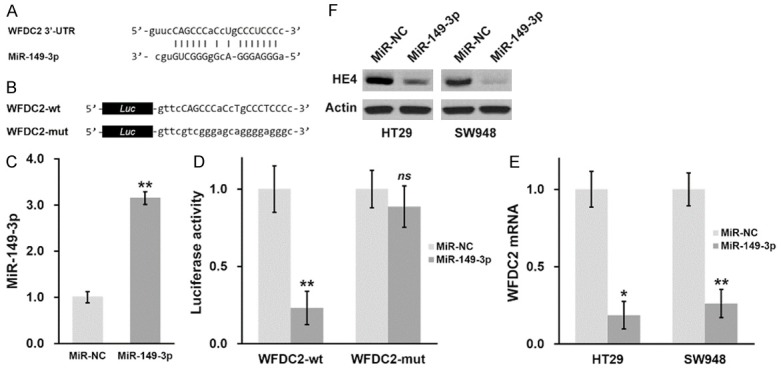

Our previous data suggested the potential regulatory effect of miR-149 on WFDC2 expression. Close inspection of the 3’UTR region had identified a putative target motif of miR-149, as shown in Figure 2A. To experimentally validate that miR-149 regulated expression of WFDC2 via direct binding to the 3’-UTR, here we constructed 3’-UTR-fused luciferase reporter plasmids. Both wild type and the mutated putative region of WFDC2 were illustrated in Figure 2B. At the same time, we established the stable cell lines expressing either miR-149 or negative control mimics, and the relative expression of miR-149 was confirmed by real-time PCR (Figure 2C). Wild-type WFDC2 3’UTR-fused luciferase displayed significantly low activity in miR-149 expressing CRC cells, while no difference was observed between cell hosts transfected with mutated luciferase construct (Figure 2D). To exclude any possible artifact in luciferase reporter system, here we further evaluated endogenous expression of WFDC2 in HT29 and SW948 cells, and our results demonstrated that ectopic introduction of miR-149 remarkably inhibited WFDC2 (Figure 2E), which consolidated our observations from luciferase assay. Consistently, the protein levels of HE4 in HT29 and SW948 cells were markedly decreased in response to forced expression of miR-149 (Figure 2F). Our data clearly indicated that WFDC2 was the target of miR-149 in our system, which might be intimately involved in the cancer biology of CRC.

Figure 2.

MiR-149-3p directly recognizes the 3’-UTR of WFDC2 mRNA and inhibits its protein expression in CRC cells. (A) Predicted miR-149-3p targeting sequence on the 3’-UTR of WFDC2 mRNA. (B) Wild type (WFDC2-wt) targeting sequence of miR-149-3p on 3’-UTR of WFDC2 mRNA, and the mutated version (WFDC2-mut), were cloned at the downstream of the luciferase open reading frame (Luc). (C) MiR-149-3p levels were examined in CRC cells stably expressing negative control (miR-NC) or miR-149-3p mimic. (D) Luciferase activities of WFDC2-wt or WFDC2-mut constructs were examined in CRC cells stably expressing miR-NC or miR-149-3p, respectively. (E, F) WFDC2 mRNA (E) and HE4 protein (F) levels were examined in CRC cells stably expressing miR-NC or miR-149-3p, respectively. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, ns not significant, compared to miR-NC.

MiR-149-3p sensitized CRC cells to radiation both in vitro and in vivo

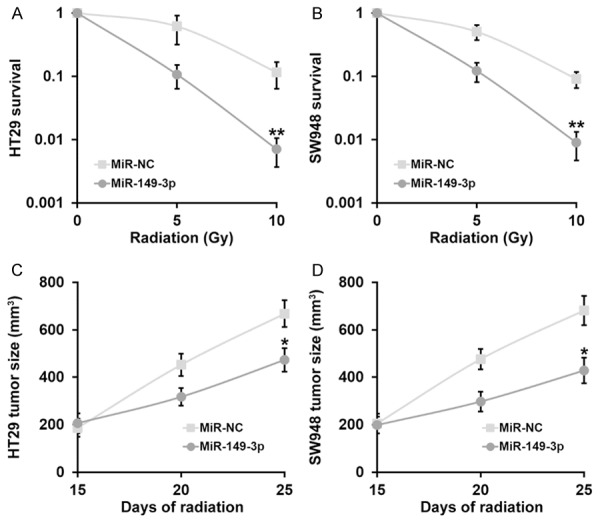

Next, we sought to investigate whether miR-149 contributed to the sensitivity of CRC to radiation via inhibiting the expression of WFDC2. To this purpose, here we first employed the stable cell lines expressing either miR-149 mimic or negative control and challenged them with radiation in vitro. The cell survival was determined by the clonogenic assay following radiation exposure. As shown in Figure 3A and 3B, the survival fraction was significantly decreased in the miR-149 expressing HT29 and SW948 cells in comparison to negative control, which indicated a great improvement with respect to the radiation resistance in both cell lines. We further explored this influence in vivo in the xenograft mouse model. Consistent with our cell line results, miR-149 remarkably suppressed xenograft growth after receiving radiation therapy (Figure 3C, 3D). Taken together, here we demonstrated that miR-149 sensitized CRC to radiation both in vitro and in vivo.

Figure 3.

MiR-149-3p sensitizes CRC cells to radiation both in vitro and in vivo. (A, B) Viability of CRC cell lines HT29 (A) and SW948 (B) stably expressing negative control (miR-NC) or miR-149-3p mimic, after treatment with radiation dose as indicated, was evaluated by clonogenic assay. (C, D) Animals (n=10 each) were subjected to 10 Gy of radiation on day 15 and 20 after inoculation, and sizes of HT29 (C) and SW948 (D) xenograft tumors were evaluated examined on day 15, 20 and 25 after inoculation. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to miR-NC.

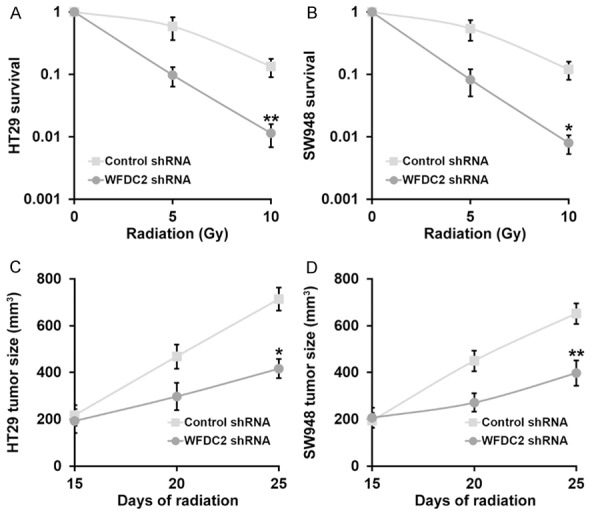

Stable WFDC2 shRNA knockdown sensitizes CRC cells to radiation both in vitro and in vivo

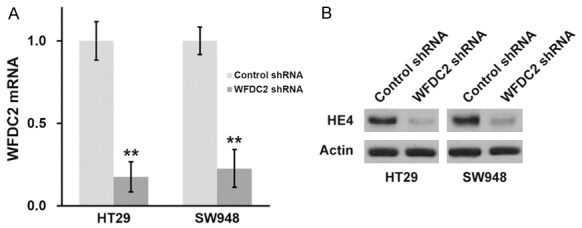

To further elucidate the crucial role of WFDC2 in radiation resistance of CRC, here we established WFDC2-deficient HT29 and SW948 cell lines using shRNAs. The effective knockdown of WFDC2 in both cell lines was validated by both real-time PCR and immunoblotting as shown in Figure 4A and 4B. Next, the response to radiation was determined in vitro via clonogenic assay. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, the cell viability was markedly compromised by radiation challenge in the WFDC2-deficient cells in comparison with control. The subcutaneous inoculation of WFDC2-knockdown cells manifested favorable response to radiation therapy as well (Figure 5C and 5D). Similar to the results acquired from miR-149 ectopic expression, here we further demonstrated straightforward that WFDC2 significantly contributed to the radiation resistance in CRC.

Figure 4.

Establishing stable WFDC2 shRNA knockdown CRC cell lines. Expressions of WFDC2 mRNA (A) and HE4 protein (B) were examined in CRC cells stably transduced with control or WFDC2 shRNA. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, compared to control shRNA.

Figure 5.

Stable WFDC2 shRNA knockdown sensitizes CRC cells to radiation both in vitro and in vivo. (A, B) Viability of CRC cell lines HT29 (A) and SW948 (B) stably transduced with with control or WFDC2 shRNA, after treatment with radiation dose as indicated, was evaluated by clonogenic assay. (C, D) Animals (n=10 each) were subjected to 10 Gy of radiation on day 15 and 20 after inoculation, and sizes of HT29 (C) and SW948 (D) xenograft tumors were evaluated examined on day 15, 20 and 25 after inoculation. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to control shRNA.

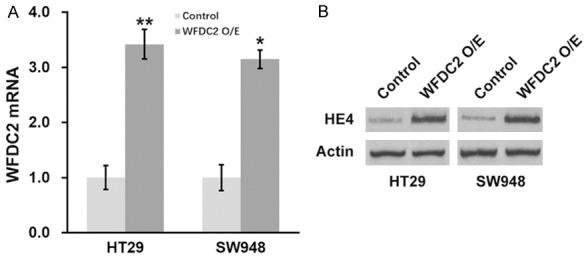

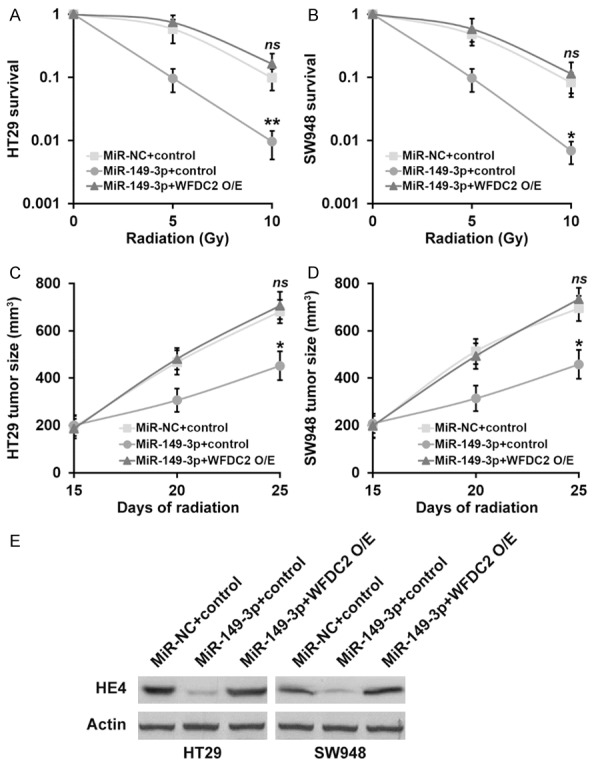

MiR-149-3p sensitizes CRC cells to radiation by inhibiting WFDC2

Although we previously demonstrated that either forced expression of miR-149 or direct knockdown of WFDC2 sensitized CRC to radiation, we still need to exclude the potential possibility that these effects functioned independent of each other. To this purpose, we established stable cell line with simultaneous overexpressions of both miR-149 and WFDC2 to conclude whether miR-149 contributed to radiation sensitivity via inhibiting WFDC2 expression. The success in establishment of double overexpression cell lines was confirmed at both transcription and translation levels (Figure 6A, 6B). Despite of the significant improvement with respect to the radiation resistance by ectopic introduction of miR-149, forced expression of WFDC2 nearly completely abolished this effect and restored the survival fractions post-radiation in both HT29 and SW948 cells (Figure 7A, 7B). The similar observations manifested in xenograft tumors, as the growth suppression imposed by radiation in miR-149-proficient cells was completely impaired in response to WFDC2 expression (Figure 7C, 7D). Furthermore, at the end of day 25, protein levels of HE4 from xenograft tumors of all experimental groups were analyzed by Western blot to confirm that HE4 protein expression was indeed regulated by miR-149-3p and WFDC2 expressions as expected (Figure 7E). Our data suggested that miR-149 sensitized CRC to radiation via directly suppression the WFDC2 expression.

Figure 6.

Establishing stable WFDC2 overexpressing CRC cell lines. Expressions of WFDC2 mRNA (A) and HE4 protein (B) were examined in CRC cells stably expressing control or WFDC2. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, compared to control.

Figure 7.

MiR-149-3p sensitizes CRC cells to radiation by inhibiting WFDC2. (A, B) Viability of CRC cell lines HT29 (A) and SW948 (B) stably expressing miR-NC or miR-149-3p mimic, as well as control and WFDC2 overexpression, after treatment with radiation dose as indicated, was evaluated by clonogenic assay. (C, D) Animals (n=10 each) were subjected to 10 Gy of radiation on day 15 and 20 after inoculation, and sizes of HT29 (C) and SW948 (D) xenograft tumors were evaluated examined on day 15, 20 and 25 after inoculation. Values are mean ± SD. **P<0.01, *P<0.05, compared to both miR-NC+control and miR-149-3p+WFDC2 O/E. ns not significant, compared to miR-NC+control. (E) At the end of day 25, protein levels of HE4 from xenograft tumors of all experimental groups were analyzed by Western blot.

Discussion

In this study, we first consolidated the previous observations of aberrant up-regulation of HE4 and down-regulation of miR-149 in CRC at both mRNA and protein levels in vitro and in vivo. We further experimentally demonstrated that miR-149 modulated WFDC2 expression via direct targeting its 3’UTR region, and identified its recognition sequence. The exogenous introduction of miR-149 markedly sensitized CRC to radiation both in vitro and in vivo. Likewise, direct abolishment of WFDC2 expression significantly improved the radiation resistance of CRC cells to comparable extent as miR-149 overexpression. However, simultaneous introduction of both miR-149 and WFDC2 completely abrogated the re-sensitization imposed by ectopic expression of miR-149 and subsequent suppression of endogenous WFDC2. Our data unambiguously demonstrated that the miR-149-WFDC2 signal axis critically contributed to the radiation sensitivity of CRC. Therefore, exogenous administration of miR-149 mimic in combination with radiotherapy might hold great promise with respect to CRC treatment clinically, which warranted further investigations and clinical trials.

Assembling data have suggested the tumor suppressive role of miR-149 in CRC. For instance, Wang et al. demonstrated that miR-149 was epigenetically silenced in CRC, and down-regulation of miR-149 was associated with hypermethylation of the neighboring CpG island, which intimately correlated with cancer progression and unfavorable prognosis [16]. The authors further identified the Specificity Protein 1, a potential oncogenic factor, as a target of miR-149 via microarray screening and other experimental validations. Bodil et al. reported that miR-149 was down-regulated in colorectal carcinoma tissues and inversely correlated to SRPX2 expression, which was further up-regulated by non-CpG promoter hypomethylation and consequently contributed to oncogenesis of CRC [17]. Xu et al. suggested that low miR-149 significantly correlated with lymph node or distant metastasis and advanced TNM stage of CRC patients, and supplement of miR-149 remarkably inhibited growth, migration and invasion of CRC cells via targeting FOXM1 [18]. In agreement with these observations, here we confirmed the aberrant down-regulation of miR-149 in CRC both in vivo and in vitro. Moreover, we further demonstrated that miR-149 positively correlated with radiation sensitivity of CRC via direct inhibiting WFDC2 expression besides its previously established involvement in tumorigenesis and progression. Our data indicated that miR-149 was a multifaceted tumor suppressor in CRC with a variety of target genes. Notably, the tumor suppressive role of miR-149 has been uncovered in other human malignancies.

As a protease inhibitor, HE4 has been increasingly recognized to be involved in cancer biology, and deregulation of HE4 has been characterized in a wide range of tumors. For example, Drapkin et al. demonstrated that the secreted HE4 was overexpressed by serous and endometrial ovarian carcinomas [19]. Hellstrom et al. identified high expression of HE4 in ovarian carcinoma as well, and proposed HE4 as a biomarker [20]. Huhtinen et al. suggested that serum HE4 concentration could differentiate malignant ovarian tumors from ovarian endometriotic cysts [21]. Lee et al. further demonstrated that HE4 associated with chemo-resistance and unfavorable prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer [22]. Zeng et al. showed that serum HE4 might be the better biomarker for early lung cancer diagnosis [23]. The recombinant HE4 significantly promoted proliferation of pancreatic and endometrial cancer cell lines [24]. Ribeiro et al. demonstrated that HE4 promoted collateral resistance to cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer cell [25]. Most recently, Kemal et al. observed high expression of HE4 in CRC patients, which correlated with tumor progression for the first time and proposed HE4 as a useful biomarker for particular stage III-IV patients [13]. Consistently, our results from both in vitro and in vivo models supported the up-regulation of HE4 in CRC. Furthermore, our data for the first time suggested that aberrant expression of HE4, which was directly subjected to miR-149 regulation, was closely related to radiotherapy resistance. Based on our results, both suppression of HE4 and exogenous introduction of miR-149 manifested great potential in restoring radiation sensitivity, which preliminarily provided a novel strategy to circumvent the intrinsic resistance to radiotherapy of CRC patients.

Notably, the regulatory mechanism underlying the low expression of endogenous miR-149 in CRC has not been addressed in this study. In view of the previous reports with respect to the critical role of epigenetic modification in regulating the expression of miR-149, here we hypothesize that the fundamental epigenetic reprogramming in CRC, especially with microsatellite instability, might suppress miR-149 expression, which in turn alleviates the inhibitory effect on WFDC2 and up-regulates HE4, and consequently contributes to the radiation resistance occurrence. Our data demonstrated that HE4 was a downstream target of miR-149, which significantly highlighted the critical importance of miR-149-WFDC2 axis underlying the sensitivity of CRC to radiotherapy and offered a promising target for therapeutic exploitations.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner H, Kloor M, Pox CP. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1490–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, Lynch HT, Minsky B, Nordlinger B, Starling N. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375:1030–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jawad N, Direkze N, Leedham SJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and colon cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;185:99–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-03503-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He J, Efron JE. Screening for colorectal cancer. Adv Surg. 2011;45:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein A, Atanackovic D, Bokemeyer C. Current standards and new trends in the primary treatment of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47(Suppl 3):S312–314. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(11)70183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nesseler JP, Peiffert D, Vogin G, Nickers P. [Cancer, radiotherapy and immune system] . Cancer Radiother. 2017;21:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shadad AK, Sullivan FJ, Martin JD, Egan LJ. Gastrointestinal radiation injury: prevention and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:199–208. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andreassen CN, Grau C, Lindegaard JC. Chemical radioprotection: a critical review of amifostine as a cytoprotector in radiotherapy. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2003;13:62–72. doi: 10.1053/srao.2003.50006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasanna PG, Stone HB, Wong RS, Capala J, Bernhard EJ, Vikram B, Coleman CN. Normal tissue protection for improving radiotherapy: Where are the Gaps? Transl Cancer Res. 2012;1:35–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chhikara N, Saraswat M, Tomar AK, Dey S, Singh S, Yadav S. Human epididymis protein-4 (HE-4): a novel cross-class protease inhibitor. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47672. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Kirchhoff C, Habben I, Ivell R, Krull N. A major human epididymis-specific cDNA encodes a protein with sequence homology to extracellular proteinase inhibitors. Biol Reprod. 1991;45:350–357. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod45.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemal YN, Demirag GN, Bedir AM, Tomak L, Derebey M, Erdem DL, Gor U, Yucel I. Serum human epididymis protein 4 levels in colorectal cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol. 2017;7:481–485. doi: 10.3892/mco.2017.1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calin GA, Croce CM. MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7390–7394. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang F, Ma YL, Zhang P, Shen TY, Shi CZ, Yang YZ, Moyer MP, Zhang HZ, Chen HQ, Liang Y, Qin HL. SP1 mediates the link between methylation of the tumour suppressor miR-149 and outcome in colorectal cancer. J Pathol. 2013;229:12–24. doi: 10.1002/path.4078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oster B, Linnet L, Christensen LL, Thorsen K, Ongen H, Dermitzakis ET, Sandoval J, Moran S, Esteller M, Hansen TF, Lamy P, group Cs, Laurberg S, Orntoft TF, Andersen CL. Non-CpG island promoter hypomethylation and miR-149 regulate the expression of SRPX2 in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:2303–2315. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu K, Liu X, Mao X, Xue L, Wang R, Chen L, Chu X. MicroRNA-149 suppresses colorectal cancer cell migration and invasion by directly targeting forkhead box transcription factor FOXM1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;35:499–515. doi: 10.1159/000369715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drapkin R, von Horsten HH, Lin Y, Mok SC, Crum CP, Welch WR, Hecht JL. Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) is a secreted glycoprotein that is overexpressed by serous and endometrioid ovarian carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2162–2169. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellstrom I, Raycraft J, Hayden-Ledbetter M, Ledbetter JA, Schummer M, McIntosh M, Drescher C, Urban N, Hellstrom KE. The HE4 (WFDC2) protein is a biomarker for ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3695–3700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huhtinen K, Suvitie P, Hiissa J, Junnila J, Huvila J, Kujari H, Setala M, Harkki P, Jalkanen J, Fraser J, Makinen J, Auranen A, Poutanen M, Perheentupa A. Serum HE4 concentration differentiates malignant ovarian tumours from ovarian endometriotic cysts. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1315–1319. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S, Choi S, Lee Y, Chung D, Hong S, Park N. Role of human epididymis protein 4 in chemoresistance and prognosis of epithelial ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43:220–227. doi: 10.1111/jog.13181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng Q, Liu M, Zhou N, Liu L, Song X. Serum human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) may be a better tumor marker in early lung cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2016;455:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu Q, Chen H, Senkowski C, Wang J, Wang X, Brower S, Glasgow W, Byck D, Jiang SW, Li J. Recombinant HE4 protein promotes proliferation of pancreatic and endometrial cancer cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2016;35:163–170. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ribeiro JR, Schorl C, Yano N, Romano N, Kim KK, Singh RK, Moore RG. HE4 promotes collateral resistance to cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer cells. J Ovarian Res. 2016;9:28. doi: 10.1186/s13048-016-0240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]