Abstract

Maternal immune activation (MIA) contributes to behavioral abnormalities relevant to schizophrenia in adult offspring, although the molecular mechanisms underlying MIA-induced behavioral changes remain unclear. Here we demonstrated that dietary intake of glucoraphanin (GF), the precursor of a natural antioxidant sulforaphane, during juvenile and adolescent stages prevented cognitive deficits and loss of parvalbumin (PV) immunoreactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) of adult offspring after MIA. Gene set enrichment analysis by RNA sequencing showed that MIA caused abnormal expression of centrosome-related genes in the PFC and hippocampus of adult offspring, and that dietary intake of GF improved these abnormal gene expressions. Particularly, MIA increased the expression of suppressor of fermentation-induced loss of stress resistance protein 1 (Sfi1) mRNA in the PFC and hippocampus of adult offspring, and dietary intake of GF prevented the expression of Sfi1 mRNA in these regions. Interestingly, we found altered expression of SFI1 in the postmortem brains and SFI1 mRNA in hair follicle cells from patients with schizophrenia compared with controls. Overall, these data suggest that centrosome-related genes may play a role in the onset of psychosis in offspring after MIA. Therefore, dietary intake of GF-rich vegetables in high-risk psychosis subjects may prevent the transition to psychosis in young adulthood.

Introduction

The onset of schizophrenia, a chronic and severe mental disorder, usually occurs in young adulthood1,2. Among three major symptoms (e.g. positive symptom, negative symptom, cognitive impairment), cognitive impairment is the core symptom of schizophrenia3–5. Interestingly, cognitive impairment can be detected before the onset of schizophrenia6,7. Therefore, there are increasing interests in the potential benefit of early intervention by nutritional antioxidants in schizophrenia since oxidative stress plays a role in the prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia8–14.

The transcription factor Nuclear factor (erythroid 2-derived)-like 2 (Nrf2) and Keap1 (Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived protein with CNC homology [ECH]-associated protein 1) system plays a central role in cellular defense against oxidative stress15,16. Thus, the Keap1–Nrf2 system is involved in attenuating oxidative stress-associated pathogenesis of a number of disorders15,16. The potent antioxidant and naturally occurring compound sulforaphane (SFN; 1-isothiocyanato-4-methylsulfinylbutane) is an organosulfur compound derived from a glucosinolate precursor glucoraphanin (GF) (Fig. 1a), which is found in cruciferous vegetables such as broccoli17,18. We reported that SFN could attenuate behavioral abnormalities in mice after the administration of a psychostimulant methamphetamine19 or N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antagonist phencyclidine (PCP)20. Furthermore, we reported that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellet during juvenile and adolescent stages could prevent the onset of cognitive deficits after repeated PCP administration21. These findings suggest that SFN (or GF) may have prophylactic and therapeutic effects on cognitive impairment and psychosis in psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia.

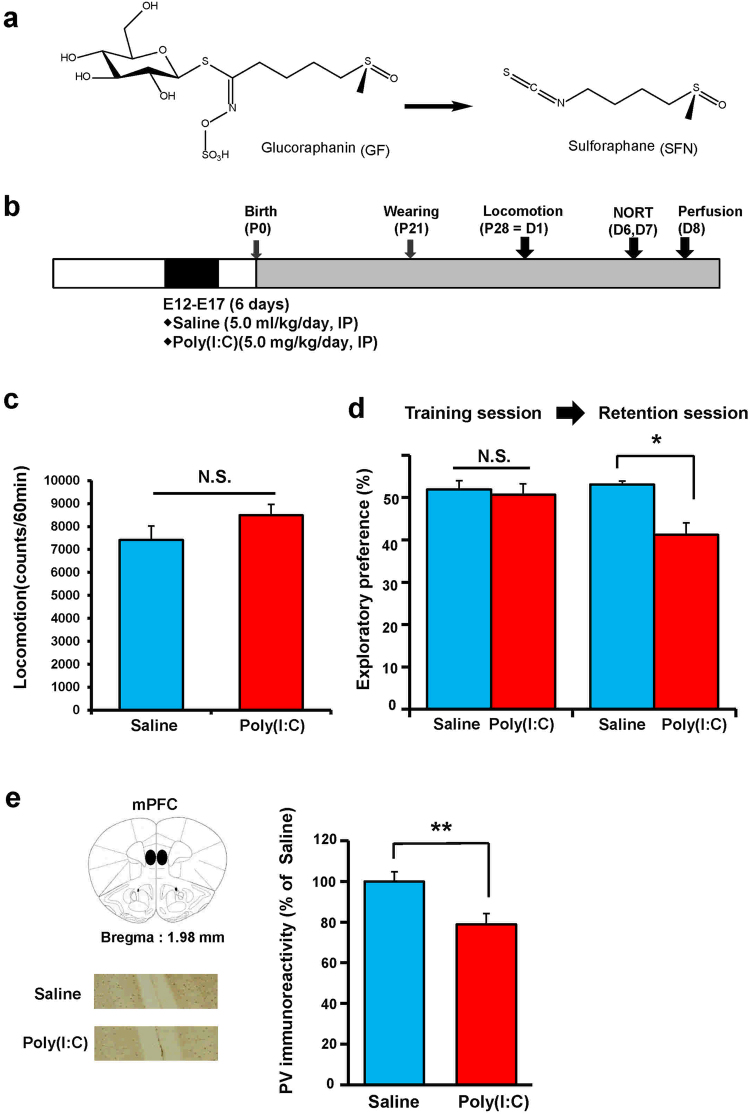

Figure 1.

Cognitive deficits in the juvenile offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure. (a) Chemical structure of sulphoraphane (SFN) and its precursor glucoraphanin (GF). (b) Schedule of treatment and behavioral tests. Saline (5.0 ml/kg/day) or poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day from E12 to E17) was injected into pregnant mice. Behavioral tests including locomotion (LMT: P28 = D1) and novel object recognition test (NORT: D6 and D7) were performed. Brain samples for immunohistochemistry were collected at D8. (c) Locomotion: There was no difference (P = 0.908) between ploy(I:C) group and saline-treated group. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8). (d) NORT: There was no difference (P = 0.282) between the two groups in the training session. In the retention session, the exploratory preference of poly(I:C) group was significantly (P = 0.048) lower than saline-treated group. *P < 0.01 compared with saline-treated group. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8). (e) Brain atlas of medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and representative data of PV-immunoreactivity in the mPFC of juvenile offspring after MIA: The PV-immunoreactivity in the mPFC of poly(I:C)-treated group was significantly (P = 0.005) lower than that of saline-treated group. **P < 0.01, compared with saline-treated group. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8).

Emerging epidemiologic data state that gestational exposure to infection contributes to the etiology of schizophrenia22–24. Maternal immune activation (MIA) using polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidilic acid [(poly(I:C)], a Toll-like receptor 3 agonist, has been widely used as a neurodevelopmental animal model for schizophrenia25–32. MIA contributes to behavioral abnormalities relevant to schizophrenia in adult offspring, although the molecular mechanisms underlying MIA-induced behavioral changes remain unclear26,27.

The present study aimed to examine whether dietary intake of GF food pellets during juvenile and adolescent stages could prevent the onset of behavioral abnormalities relevant to schizophrenia in adult offspring after MIA. Furthermore, we examined the molecular mechanisms of GF’s beneficial effects in MIA model using RNA-sequencing and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA).

Results

Behavioral data and PV-immunohistochemistry of juvenile offspring after MIA

First, we performed behavioral tests (locomotion and NORT) and parvalbumin (PV) immunohistochemistry in juvenile offspring after MIA because the reduction of PV immunoreactivity in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) might be related with cognitive impairment and psychosis28,33,34. Behavioral tests of juvenile offspring were performed at P28–P35 after prenatal poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day from E12 to E17) injections (Fig. 1b). In the open field test, there was no difference between the control and poly(I:C)-treated groups (Fig. 1c). In NORT, there was no difference between the two groups during the training session (Fig. 1d). However, during the retention session, the exploratory preference of the poly(I:C)-treated group was significantly lower than that of the control group (Fig. 1d). PV-immunoreactivity (PV-IR) in the mPFC of juvenile offspring of the poly(I:C)-treated group was significantly lower than that in the saline-treated (control) group (Fig. 1e). These findings suggest that juvenile offspring of prenatal poly(I:C)-treated mice showed the reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC, resulting in cognitive deficits.

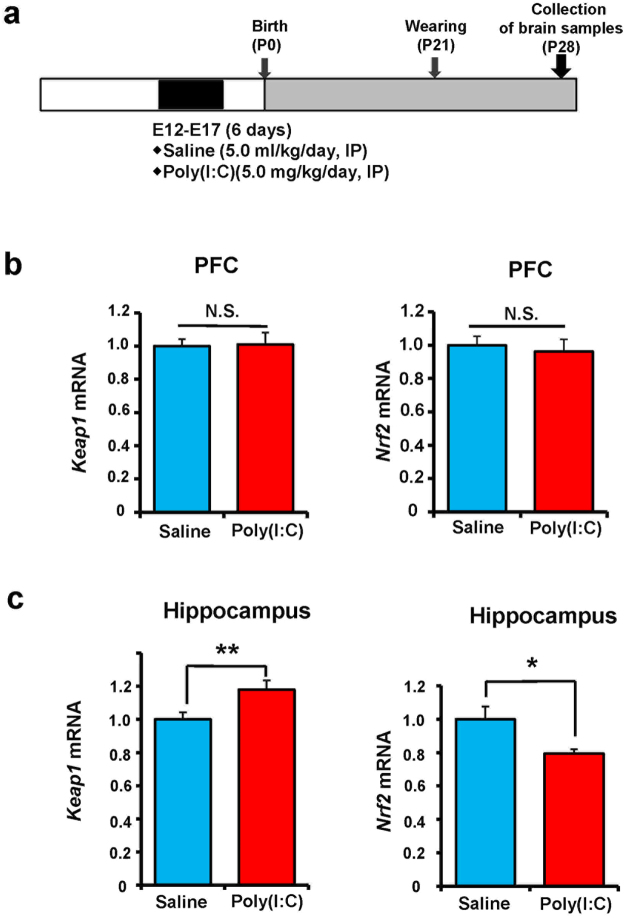

Gene expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus from juvenile offspring after MIA

We measured Keap1 and Nrf2 gene expressions in the PFC and hippocampus of juvenile offspring (4-week-old) after MIA (Fig. 2a). The expressions of these two genes in the PFC were not different between the two groups (Fig. 2b). However, Keap1 mRNA expression in the hippocampus was significantly higher, whereas Nrf2 mRNA expression in the poly(I:C)-treated group was significantly lower than that of control group (Fig. 2c). These findings suggest that abnormalities in Keap1–Nrf2 signaling in the hippocampus may play a role in the behavioral abnormality of juvenile offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) injections.

Figure 2.

Gene expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the PFC and hippocampus of juvenile offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure. (a) Schedule of treatment and collection of brain samples. (b) There were no changes for gene expression of Keap1 (P = 0.903) and Nrf2 (P = 0.794) in the PFC. (c) There were significant changes for gene expression of Keap1 (P = 0.012) and Nrf2 (P = 0.023) in the hippocampus. Data represent the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 10 for saline-treated group, n = 14 for poly(I:C) group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared with saline-treated group. NS: not significant.

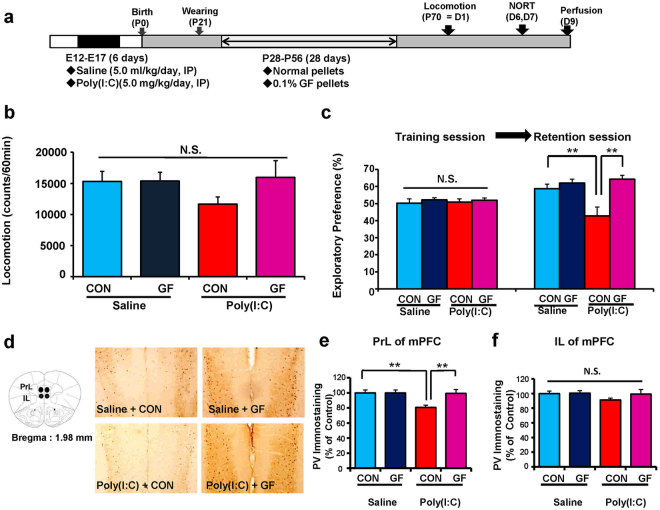

Effects of dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets during juvenile and adolescent stages on cognitive deficits and reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC of adult offspring after MIA

We examined whether dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets during juvenile and adolescent stages could prevent cognitive deficits and reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC of adult offspring after MIA. Offspring (4-week-old) were divided into normal food pellet and 0.1% GF-containing food pellet groups. The mice were given free access to water and both the food pellets that were specifically designed for mice for 4 weeks (P28–P56). Subsequently, normal food pellets were given to both the groups. Behavioral tests of adult offspring were performed during adulthood (P70–P84) after prenatal poly(I:C) injections (Fig. 3a). In the open field test, locomotion was unchanged among the four groups (Fig. 3b). There was no difference among the four groups in NORT training sessions. However, in the retention session of NORT, the exploratory preference of the poly(I:C) + GF group was significantly higher than that of the poly(I:C) + control group (Fig. 3c). These findings suggest that dietary intake of 0.1% GF pellets from P28 to P56 improved cognitive deficits in adult offspring after MIA.

Figure 3.

Effects of dietary intake of 0.1% GF on cognitive deficits in the adult offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure. (a) Schedule of treatment and behavioral tests. Saline (5 ml/kg/day) or poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day from E12 to E17) was injected into pregnant mice. Normal food pellets or 0.1% GF food pellets were given to juvenile offspring from D28 to D56. Subsequently, normal food pellets were given to all mice for 14 days (D57-). Brain samples were collected at D70. (b) Locomotion: There was no difference (poly(I:C): F1,29 = 0.7555, P = 0.3919; GF: F1,29 = 1.515, P = 0.2282; interaction: F1,29 = 1.434, P = 0.2408) among the four groups. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8 for saline + control pellet group, n = 8 for saline + GF pellet group, n = 9 for poly(I:C) + control pellet group, n = 8 for poly(I:C) + GF pellet group). (c) NORT: There was no difference (poly(I:C): F1,29 = 0.019, P = 0.891; GF: F1,29 = 0.891, P = 0.390; interaction: F1,29 = 0.057, P = 0.812) among the four groups in the training session. In the retention session, the exploratory preference of poly(I:C) + GF pellet group was significantly (poly(I:C): F1,29 = 3.346, P = 0.048; GF: F1,29 = 10.943, P = 0.003; interaction: F1,29 = 5.832, P = 0.022) higher than poly(I:C) + control pellet group. **P < 0.01 compared with poly(I:C) + control pellet group. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8 for saline + control pellet group, n = 8 for saline + GF pellet group, n = 9 for poly(I:C) + control pellet group, n = 8 for poly(I:C) + GF pellet group). (d) Brain atlas of PrL and IL regions of mPFC and representative data of PV-immunoreactivity in the mPFC of juvenile offspring. (e) The PV-immunoreactivity in the PrL of mPFC of poly(I:C) + GF pellet group was significantly (poly(I:C): F1,29 = 5.798, P = 0.023; GF: F1,29 = 4.992, P = 0.033; interaction: F1,29 = 4.992, P = 0.033) higher than that of poly(I:C) + control pellet group. **P < 0.01, compared with poly(I:C) + control pellet group. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8). (f) The PV-immunoreactivity in the IL of mPFC was not different (poly(I:C): F1,29 = 1.597, P = 0.216; GF: F1,29 = 1.113, P = 0.300; interaction: F1,29 = 0.8391, P = 0.367) among the four groups. The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 8).

Furthermore, we performed PV immunohistochemistry at adulthood (10 weeks) (Fig. 3d and e). PV-IR in the PrL (not IL) of the mPFC of the poly(I:C) + GF group was significantly higher than that in the poly(I:C) + control group (Fig. 3e). These findings suggest that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets from P28 to P56 prevented the reduction of PV-IR in the PrL of the mPFC in adult offspring after MIA.

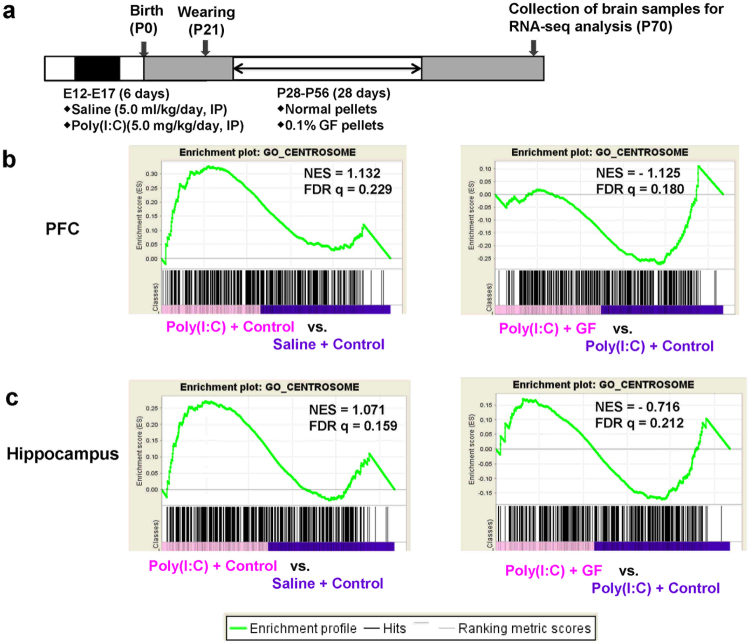

RNA-sequencing and GSEA

To study the molecular targets for the beneficial effects of dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets, we performed RNA sequencing of the PFC and hippocampus from the four groups of adult offspring. The most important finding using gene set enrichment analysis was that centrosome-related genes played a key role in the molecular mechanisms underlying the beneficial effects of GF dietary intake in the MIA model (Fig. 4a–c). The centrosome is involved in many different cell processes, particularly cell division, cell migration, and differentiation. Accumulating evidence suggests a central role of centrosome at late stages of neuronal development35. Among the centrosome genes, we found a significant change in suppressor of fermentation-induced loss of stress resistance 1 (Sfi1) expression, which is localized in the centriole and involved in cell division36,37. We measured the expression of Sfi1 mRNA and SFI1 levels in subsequent experiments. The expression of Sfi1 mRNA in the PFC and hippocampus of adult offspring was significantly increased by prenatal poly(I:C) injection, whereas dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets significantly blocked the increase in this gene expression (Figs. 5a–c).

Figure 4.

RNA-sequencing analysis and GSEA of brain samples from adult offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure. (a) Schedule of treatment and behavioral tests. Saline (5 ml/kg/day) or poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day from E12 to E17) was injected into pregnant mice. Normal food pellets or 0.1% GF food pellets were given to juvenile offspring from D28 to D56. Subsequently, normal food pellets were given to all mice for 14 days (D57-). Brain samples were collected at D70, and RNA-sequencing analysis was performed. (b,c) The GSEA (gene set enrichment analysis) plots showing enrichment of centrosome-related gene sets in the PFC (b) and Hippocampus (c). The normalized enrichment scores (NES) and false discovery rate q value (FDR q) were indicated.

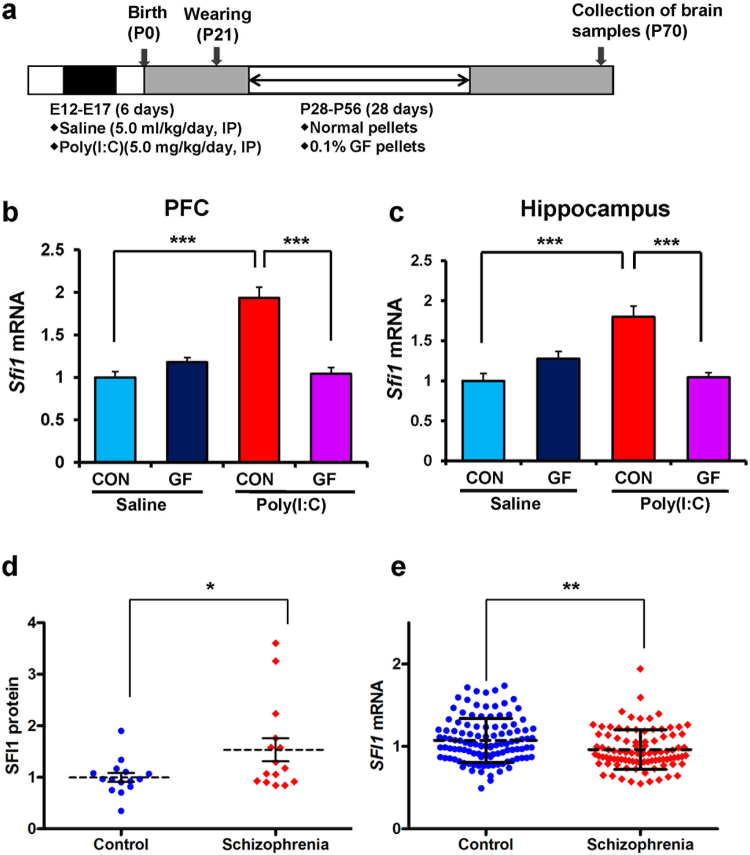

Figure 5.

Expression of Sfi1 mRNA in the PFC and hippocampus from the adult offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure and expression of SFI1 protein and SFI1 mRNA in schizophrenia. (a) Schedule of treatment and behavioral tests. Saline (5 ml/kg/day) or poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day from E12 to E17) was injected into pregnant mice. Normal food pellets or 0.1% GF food pellets were given to juvenile offspring from D28 to D56. Subsequently, normal food pellets were given to all mice for 14 days (D57-). Brain samples were collected at D70. (b): Sfi1 mRNA in the PFC: There was significant effects (poly(I:C): F1,22 = 25.39, P < 0.001; GF: F1,22 = 20.28, P < 0.001; interaction: F1,22 = 45.97, P < 0.001). (c) Sfi1 mRNA in the hippocampus: There was significant effects (poly(I:C): F1,22 = 9.29, P = 0.006; GF: F1,22 = 6.65, P = 0.017; interaction: F1,22 = 31.01, P < 0.001). The value is expressed as the mean ± S.E.M. (n = 5–7). ***P < 0.001 compared to poly(I:C) + control group. (d) Expression of SFI1 protein in the parietal cortex from patients (n = 15) with schizophrenia was significantly (P = 0.034) higher than that of controls (n = 15). The value is expressed as the mean ± S.D. *P < 0.05 compared to control group. (e) Expression of SFI1 mRNA in the hair-follicle from patients (n = 94) with schizophrenia was significantly (P = 0.002) lower than that of controls (n = 117). The value is expressed as the mean ± S.D. **P < 0.01 compared to control group.

Measurements of SFI1 protein in the postmortem brain samples and SFI1 mRNA in hair follicle cells from schizophrenia

Western blot analysis showed that SFI1 expression in the parietal cortex of patients with schizophrenia (Table 1) was significantly higher than that of controls (Fig. 5d). To test whether the expression of SFI1 mRNA is associated with the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, we measured SFI1 mRNA expression in hair follicle cells from schizophrenic and healthy control subjects (Table 2)33,34. The SFI1 mRNA expression in the hair follicle cells of patients with schizophrenia was significantly lower than that of healthy controls (Fig. 5e). Correlation analyses demonstrated no significant effects of age, dose of antipsychotics, or duration of illness on SFI1 mRNA expression.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the postmortem samples from Neuropathology Consortium of the Stanley Medical Research Institute.

| Characteristics | Control (n = 15) | Schizophrenia (n = 15) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at death (years) | 48.1 ± 10.7 (29–68) | 44.5 ± 13.1 (25–62) | 0.425a |

| Gender (male/female) | 9/6 | 9/6 | 1.000b |

| PMI (hrs) | 23.7 ± 9.95 | 33.7 ± 14.6 | 0.038a |

| Brain pH | 6.27 ± 0.24 | 6.16 ± 0.26 | 0.250a |

| Brain hemispheres (right/left) | 7/8 | 6/9 | 0.713b |

| Brain weight (g) | 1501.0 ± 164.1 | 1471.7 ± 108.2 | 0.568a |

| Storage days | 338.2 ± 234.2 | 621.1 ± 233.1 | 0.003a |

| Age of onset (years) | 23.2 ± 8.0 | ||

| Duration of disease (years) | 21.3 ± 11.4 | ||

| Fluphenazine equivalent (mg) | 52267 ± 62062 (1 never) |

The data are shown the mean ± S.D. PMI: postmortem interval. aUnpaired t-test, bx2 test for independence.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the hair-follicle samples from control and schizophrenia.

| Characteristics | Control (n = 117) | Schizophrenia (n = 94) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 43.9 ± 13.1 (21–73) | 50.5 ± 11.8 (21–72) | <0.001a |

| Gender (male/female) | 50/67 | 49/45 | 0.174b |

See the ref.24. The data are shown the mean ± S.D. aUnpaired t-test, bx2 test for independence.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellets during the juvenile and adolescent stages of offspring after MIA prevented cognitive deficits and reduction of PV-IR in the PrL of the mPFC at adulthood after MIA. Furthermore, centrosome signaling via Sfi1 might play a role in the development of behavioral abnormalities in adult offspring after MIA, as well as in the beneficial effects of 0.1% GF dietary intake. Finally, we found altered expressions of SFI1 in the parietal cortex and SFI1 mRNA in hair follicle cells of patients with schizophrenia, suggesting that abnormal expression of SFI1 plays a role in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. These all findings suggest that altered centrosome signaling through Sfi1 might play a role in the development of behavioral abnormalities after MIA as well as in the beneficial effects of GF dietary intake. Therefore, it is likely that supplementation with GF-rich food in subjects with a high-risk for psychosis has prophylactic effects on the psychotic behaviors relevant to schizophrenia and related disorders in adulthood.

We found cognitive deficits of juvenile offspring from poly(I:C)-treated mice, consistent with previous reports28,29. Since cognitive impairment is seen in adolescent and young adult with a high risk for psychosis6,7, it seems that the juvenile offspring after MIA may be at the prodromal stage for psychosis28,29. Furthermore, we found reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC at juvenile offspring after MIA, which is consistent with the previous study28. It is well known that reduction of PV-IR in the PFC may contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia33,34. Therefore, it is likely that reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC may play a crucial role in the cognitive deficits of juvenile offspring after MIA.

Furthermore, we found abnormal expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 genes in the hippocampus of juvenile offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure, although expression of these genes in the PFC remained the same. Thus, it seems that abnormalities in the Keap1-Nrf2 system in the hippocampus might play a role in the cognitive deficits seen in juvenile offspring after MIA. Recently, we reported decreased gene expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor subtypes, Grin1, Grin2a, and Grin2b in the hippocampus (but not PFC) of juvenile offspring after prenatal poly(I:C) exposure29. Taken together, it is likely that MIA can interfere with Keap1-Nrf2 system and NMDA receptor in the hippocampus during brain development, resulting in cognitive deficits in juvenile and adult offspring. A recent study showed that the expressions of Keap1 and Nrf2 in the parietal cortex from patients with schizophrenia were lower than those of controls, suggesting that Keap-Nrf2 signaling may play a role in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia38. Nonetheless, further detailed studies on how prenatal poly(I:C) exposure induces the Keap1-Nrf2 system and behavioral abnormalities in juvenile and adulthood are needed.

We found reduction of PV-IR in the PrL, but not IL, of mPFC at adult offspring after MIA, consistent with the previous findings28,39. Reduction of PV-IR cells in the PFC is suggested to contribute to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia33,34. Interestingly, we found that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellet at 4–8 weeks of age (similar to juvenile and adolescent stages in human) in poly(I:C) offspring could treat or prevent cognitive deficits and reduction of PV-IR at adulthood after MIA. Prenatal infection may contribute to the onset of neurodevelopmental disorders in their offspring40, and alterations in the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in the hippocampus may play a role in MIA-induced abnormal brain neurodevelopment. Previously, we reported that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellet might prevent the onset of cognitive deficits and reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC after repeated PCP administration21. Furthermore, we also reported that dietary intake of 0.1% GF food pellet could prevent the onset of depression-like phenotype in mice after chronic social defeat stress41 or inflammation42. Taken together, it is likely that early intervention with GF (or SFN)-rich foods during juvenile and adolescent stages might have prophylactic and therapeutic effects on abnormal behaviors in psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia and depression21,41,42.

The centrosome is the main microtubule organizer in mammalian cells, participating in a variety of processes from cell polarization to cell division35. In this study, SFI1 mRNA expression in the hair follicle cells of patients with schizophrenia was lower than that of healthy controls although SFI1 protein expression in the parietal cortex from patients with schizophrenia was higher than that of controls. The reasons underlying this discrepancy are currently unclear, the findings are similar to the previous report (FABP4 mRNA in hair follicle and postmortem brain)43. Mutations in genes encoding centrosomal components are associated with several neurological and psychiatric disorders, such as schizophrenia. For example, mutations in the centrosomal genes lissencephaly 1 (LIS1) and doublecortin (DCX), have been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders35, while the centrosome gene disrupted-in-schizophrenia-1 (DISC1) is a candidate susceptibility gene for schizophrenia44. A recent study demonstrated that DISC1 regulates Ndel1’s kinetochore attachment, but not its centrosome localization, during mitosis, and that disrupting DISC1/Ndel1 complex formation prolongs mitotic length and interferes with cell cycle progression in human cells45. Furthermore, alterations in the expression of Sfi1 in the striatum and hippocampus of 39,XY*O mice, a genetic model of neurodevelopmental disorder have been reported46. Moreover, copy number variants encompassing SFI1 on chromosome 22q12.2 have been identified in neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD)47–49. It is noteworthy that beneficial effects of SFN have been shown in young subjects with ASD50.

Adolescence is more vulnerable to psychiatric disorders since adolescence is a critical period of brain neurodevelopment1,51. The study also supports for the deleterious effects of early brain insult on abnormalities in brain neurodevelopment21,28,52. Furthermore, it is known that adolescence is the peak time for the onset of a number of psychiatric disorders. Therefore, it seems that cognitive impairment at adolescence may present prodromal symptoms for later onset of these disorders28–30. Therefore, it is likely that early intervention by the nutritional antioxidants in young peoples at high risk for psychosis might play a crucial role in preventing the onset of psychosis.

This paper has some limitations: Postmortem interval (PMI) and storage days of postmortem brain samples were significantly different from the two groups. Furthermore, age from the hair-follicle samples was significantly different from the two groups. These parameters may affect the expression of SFI1 protein and SFI1 mRNA in the human samples. Further study using controls with matched for these parameters will be needed.

In conclusion, the present data suggest that abnormal modulation of centrosome-related genes plays a role in the behavioral abnormality and reduction of PV-IR in the mPFC of offspring after MIA. Interesting, through the centrosome modulation, dietary intake of 0.1% GF during juvenile and adolescent stage could prevent the onset of psychosis in the adult offspring after MIA. Finally, supplementation of SFN (or GF)-rich vegetables in young peoples at high risk for psychosis may prevent the transition to actual psychosis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Pregnant ddY mice (embryo at the 5th day (E5), 9–10 weeks old) were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). Pregnant mice in each clear polycarbonate cage (22.5 × 33.8 × 14.0 cm) one by one were under a controlled 12/12 h light–dark cycle (lights on from 07:00 a.m. to 07:00 p.m.), with room temperature at 23 ± 1 °C and humidity at 55 ± 5%. The mice were kept free access to water and pellets. The experimental procedure using animals was approved by the Chiba University Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health, USA.

The study using postmortem brain samples was approved by Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University. The study using the samples of scalp hair-follicle was also approved by the Ethics Committees of RIKEN and all participating institutes43,53. This study was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. All subjects gave written, informed consent to participate in the study after the study protocols and objectives were explained43,53.

Administration of poly(I:C) into pregnant mice

The schedule of poly(I:C) treatment was performed as reported previously25,28–30. The pregnant mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) for six consecutive days from E12 to E17 with poly(I:C) (5.0 mg/kg/day, Sigma-Aldrich Co. Ltd., St. Louis, MO, USA) dissolved in physiological saline, or an equivalent volume (5 ml/kg) of saline. The male offspring were separated from their mothers after 3 weeks, and mice were caged each three or five in the groups.

Preparation of 0.1% glucoraphanin (GF) food pellets

Food pellets (CE-2; Japan CLEA, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) containing 0.1% glucoraphanin (GF) were prepared as reported previously20,41,42. Basically, broccoli sprout extract powder containing GF (a precursor of SFN) was industrially produced by KAGOME CO., LTD (Nasushiobara, Tochigi, Japan). In brief, broccoli sprout was grown from specially selected seeds (Brassica Protection Products LLC., Baltimore, MD, USA) for 1 day after the germination. On the 1st day broccoli sprout was plunged into boiling water and maintained at 95 °C for 30 minutes, and the sprout residues was removed by filtration. The boiling water extract was mixed with a waxy corn starch dextrin and then spray dried to yield the broccoli sprout extract powder containing 135 mg (approx. 0.31 mmol) of GF per gram. For preparing the animal diet containing 0.1% GF (approx. 2.3 mmol GF per 1 kg-diet), the extract powder was mixed with a basal diet CE-2, and then pelletized at a processing facility (Oriental Yeast Co., ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The GF content in the diet was determined by high performance liquid chromatography as previously described21,41,42.

Behavioral analysis

Locomotion and the novel object recognition test (NORT) were performed as reported previously20,28,29. Locomotor Activity: Both horizontal and rearing activity were monitored by an infrared ray passive sensor system (SCANET-SV10, Melquest Ltd., Toyama, Japan), and activity was integrated every minute. Individual mice were placed in activity chambers and allowed 1 hour of free exploration as spontaneous activity.

Novel Object Recognition Test (NORT): Mice were habituated for 10 minutes in the box for 3 straight days. At 4th day, two objects (differing in shape and color but of similar size) were placed in the box 35.5 cm apart (symmetrically), and each animal was allowed to explore in the box for 5 minutes. The animals were considered to be exploring the object when the head of the animal was both facing and within 2.54 cm of the object or when any part of the body, except for the tail was touching the object. The time that mice spent exploring each object was recorded. After training, mice were immediately returned to their home cages, and the box and objects were cleaned with 75% ethanol, to avoid any possible instinctive odorant cues. Retention tests were carried out at one-day intervals, following the respective training. During the retention test, each mouse was reintroduced into their original test box, and one of the training objects was replaced by a novel object. The mice were then allowed to explore freely for 5 minutes, and the time spent exploring each object was recorded. Throughout the experiments, the objects were counter-balanced, in terms of their physical complexity and emotional neutrality. A preference index, that is, the ratio of time spent exploring either of the two objects (training session) or the novel object (retention test session) over the total time spent exploring both objects, was used.

Gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR

Nrf2 (Nfe2l2) and Keap1 mRNA: At juvenile (P28) stage, mice were sacrificed, and their brains were removed for quantification of gene expression of Nrf2 (Nfe2l2) and Keap1. The frontal cortex and hippocampus were quickly dissected on ice from whole brain. A quantitative RT-PCR system (Step One Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan) was used to measure mRNAs. The specific mRNA transcripts were quantified by TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). Expression levels of Nfe2l2 (Mm00477784_m1), and Keap1 (Mm00497268_m1) were measured. Total RNA was extracted by use of an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purity of total RNA was assessed by Bio photometer plus (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The RNA samples were used in the first strand cDNA synthesis with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (#4368813 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). All samples were tested in triplicate and average values were used for quantification. The average values were normalized to Vic-labeled Actb mRNA (#4352341E: pre-developed TaqMan Assay Reagents, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan).

Sfi1 mRNA: The expression levels of mouse Sfl1 (Mm03039570_m1) were measured. Total RNA was extracted by use of an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The purity of total RNA was assessed by Bio photometer plus (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The RNA samples were used in the first strand cDNA synthesis with High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (#4368813 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). All samples were tested in triplicate and average values were used for quantification. The average values were normalized to Vic-labeled Actb mRNA (#4352341E: pre-developed TaqMan Assay Reagents, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan).

Immunohistochemistry for Parvalbumin (PV)

Immunohistochemistry of PV was performed as reported previously28. Mice were anesthetized with 5% isoflurane and sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), and perfused transcardially with 10 mL of physiological saline, followed by 40 mL of ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). Brains were removed from the skulls and post fixed overnight at 4 °C in the same fixative. For the immunohistochemical analysis, 50 μm-thick serial, coronal sections of brain tissue were cut in ice-cold 0.01 M phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.5) using a vibrating blade microtome (VT1000s, Leica Microsystems AG, Wetzlar, Germany). Free-floating sections were treated with 0.3% H2O2 in 50 mM Tris-HCl saline (TBS) for 30 min and ware blocked in TBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (TBST) and 1.5% normal serum for 1 h at room temperature. The samples are then incubated for 24 h at 4 °C with rabbit polyclonal anti-parvalbumin (PV) antibody (1:5,000, Swant, Bellin zona, Switzerland). The sections were washed three times in TBS and then processed using the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method (Vectastain Elite ABC, Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Sections ware incubated for 3 min in a solution of 0.25 mg/mL DAB containing 0.01% H2O2. Then, sections were mounted on gelatinized slides, dehydrated, cleared, and cover slipped under Permount® (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). The sections were imaged, and the staining intensity of PV immunoreactivity in the inflalimbic (IL) and prelimbic (PrL) regions of mPFC was analyzed using a light micro-scope equipped with a CCD camera (Olymups IX70, Tokyo, Japan) and the SCION IMAGE software package. Images of sections within mPFC region were captured using a 100× objective with a Keyence BZ-X700 microscope (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan).

RNA-sequencing and gene ontology analysis

Total RNA from prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampus were isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After RNA quality check (average of RIN values = 8) with RNA nano kit (Agilent Technologies) on Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies), 4 μg of pooled total RNA (5 samples in each group) were used for preparing cDNA libraries with the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation Kit v2 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The derived cDNA libraries were analyzed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer with DNA 1000 kit and quantified by qPCR using KAPA Library Quantification Kit (KAPA Bio systems, Wilmington, MA, USA). Twelve libraries with a unique barcode were pooled in three lanes and clusters were generated on a cBot (Illumina) to obtain 100 bp single reads in a HiSeq. 2500 sequencer (Illumina). Generation of demultiplexed fastq files was performed using bcl2fastq ver. 2.17 (Illumina) and 414 million sequence reads were obtained in total. Filtering, mapping, and differential expression analysis were performed using CLC Genomics Workbench software ver. 8.5 (Qiagen). The raw sequence reads were filtered to exclude adapter sequences, ambiguous nucleotides, and low-quality sequences and the retained sequences were aligned against the mouse genome (mm10). Analysis of the biological functions was performed using Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, Ingenuity, Redwood City, CA, USA)(http://www.ingenuity.com) and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)(http://software.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp). RNA sequencing data have been deposited to the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (DRA) and are available at the accession number DRA006055.

Western blot of SFI1 protein in the postmortem brain samples from schizophrenia

Postmortem brain samples (n = 15) from schizophrenia and controls (n = 15)(Table 1) were obtained from the Neuropathology Consortium of the Stanley Medical Research Institute (MD, USA)54,55. Basically, the tissue samples were homogenized in Laemmli lysis buffer. Aliquots (50 μg for human samples) of protein were measured using a DC protein assay kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and incubated for 5 min at 95 °C with an equal volume of a mixture of 125 mM Tris/HCl, pH 6.8, 20% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 10% β-mercaptoethanol, and 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, then and subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, using 10% mini-gels (Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Gel; Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes using a Trans Blot Mini Cell (Bio-Rad). For immunodetection, the blots were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in TBST (Tris-buffered saline + 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature (RT), and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used: SFI1 (Cat#: 13550–1-AP, 1: 1,000, Proteintech Japan, Tokyo, Japan). The next day, the blots were washed three times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:5000) for 1 hour at RT. After three final washes with TBST, the bands were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence plus the Western Blotting Detection system (GE Healthcare Bioscience). The blots then were washed three times with TBST and incubated with a primary antibody against β-actin. Images were captured with a Fuji LAS3000-mini imaging system (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan) and immunoreactive bands were quantified.

RT-qPCR of SFI1 mRNA in the hair follicle samples from patients with schizophrenia

All samples (Table 2) of scalp hair-follicle were used as described in the previous work43,53. As described, expression levels of SFI1 gene (Hs01564965_m1) were measured. Total RNA was extracted by use of an RNAqueous-Micro kit (Ambion, Grand Island, New York). The RNA samples were used in the first strand cDNA synthesis with SuperScript VILO Master Mix (#11755050 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan). All samples were tested in triplicate and average values were used for quantification based on the standard curve method. The average values were normalized to GAPDH mRNA (Hs02758991_g1: VIC-labeled TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Yokohama, Japan).

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) for animal data and mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) for human data. The data of locomotion, NORT, PV-immunostaining at juvenile stage, postmortem human brain and hair-follicle samples were analyzed by Student’s t-test. The data of locomotion, NORT, and PV-immunostaining at adult stage were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed post-hoc Bonferroni test. Significance for results was set at P < 0.05. Significance for the GSEA was set at the false discovery rate (FDR) q < 0.25.

Acknowledgements

We thank to The Stanley Medical Research Institution (MD, USA) for providing the postmortem tissue samples. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to S.K., 24116008, T.Y., 24116002, & K.H., 24116006), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (to K.H., 17H04243), the Strategic Research Program for Brain Sciences from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (to M.M., JP17dm0107129, T.Y., JP17dm0107083, & K.H., JP17dm0107119), and SENSHIN Medical Research Foundation, Japan (to K.H.).

Author Contributions

K.H. designed the study and wrote the protocol. A.M., T.I., Y.F., and M.I. performed the experiments. Y.I., M.M., M.T., and T.Y. performed gene expression in the hair follicle cells from schizophrenia patients and controls. S.H., R.K.-M., and S. K. performed RNA-seq analysis. Y.U. and H.S. provided GF-including food pellet. A.M. and T.I. undertook the statistical analysis. A.M. and K.H. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:947–957. doi: 10.1038/nrn2513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin O. Developmental timing and critical windows for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Nat Med. 2016;22:1229–1238. doi: 10.1038/nm.4225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Millan MJ, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:141–168. doi: 10.1038/nrd3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kahn RS, Keefe RS. Schizophrenia is a cognitive illness: time for a change in focus. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:1107–1112. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gur RC, et al. Neurocognitive growth charting in psychosis spectrum youths. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:366–374. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fusar-Poli P, et al. Cognitive functioning in prodromal psychosis: a meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;69:562–571. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bora E, Murray RM. Meta-analysis of cognitive deficits in ultra-high risk to psychosis and first-episode psychosis: do the cognitive deficits progress over, or after, the onset of psychosis? Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:744–755. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahadik SP, Pillai A, Joshi S, Foster A. Prevention of oxidative stress-mediated neuropathology and improved clinical outcome by adjunctive use of a combination of antioxidants and omega-3 fatty acids in schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:119–131. doi: 10.1080/09540260600581993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do KQ, Conus P, Cuenod M. Redox dysregulation and oxidative stress in schizophrenia: nutrigenetics as a challenge in psychiatric disease prevention. J Nutrigenet Nutrigenomics. 2010;101:131–153. doi: 10.1159/000324366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabungcal JH, et al. Juvenile antioxidant treatment prevents adult deficits in a developmental model of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2014;83:1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawa A, Seidman LJ. Is prophylactic psychiatry around the corner? combating adolescent oxidative stress for adult psychosis and schizophrenia. Neuron. 2014;83:991–993. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto K. Targeting of NMDA receptors in new treatments for schizophrenia. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2014;18:1049–1053. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.934225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarris J, et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:271–274. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steullet P, et al. Redox dysregulation, neuroinflammation, and NMDA receptor hypofunction: A “central hub” in schizophrenia pathophysiology? Schizophr Res. 2016;176:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ma Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2013;53:401–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki T, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Toward clinical application of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2013;34:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Talalay P, Cho CG, Posner GH. A major inducer of anticarcinogenic protective enzymes from broccoli: isolation and elucidation of structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2399–2403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fahey JW, et al. Stabilized sulforaphane for clinical use: Phytochemical delivery efficiency. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61:4. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, et al. Protective effects of the antioxidant sulforaphane on behavioral changes and neurotoxicity in mice after the administration of methamphetamine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222:37–45. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirai Y, Fujita Y, Hashimoto K. Effects of the antioxidant sulforaphane on hyperlocomotion and prepulse inhibition deficits in mice after phencyclidine administration. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2012;10:97–98. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2012.10.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirai Y, et al. Dietary intake of sulforaphane-rich broccoli sprout extracts during Juvenile and adolescence can prevent phencyclidine-induced cognitive deficits at adulthood. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown AS, Derkits EJ. Prenatal infection and schizophrenia: a review of epidemiologic and translational studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:261–280. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09030361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43:239–257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weber-Stadlbauer U. Epigenetic and transgenerational mechanisms in infection-mediated neurodevelopmental disorders. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1113. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozawa K, et al. Immune activation during pregnancy in mice leads to dopaminergic hyperfunction and cognitive impairment in the offspring: a neurodevelopmental animal model of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer U. Prenatal poly(I:C) exposure and other developmental immune activation models in rodents systems. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;75:307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Estes ML, McAllister AK. Maternal immune activation: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science. 2016;353:772–777. doi: 10.1126/science.aag3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Han M, et al. Intake of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone during juvenile and adolescent stages prevents onset of psychosis in adult offspring after maternal immune activation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36087. doi: 10.1038/srep36087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujita Y, Ishima T, Hashimoto K. Supplementation with D-serine prevents the onset of cognitive deficits in adult offspring after maternal immune activation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:37261. doi: 10.1038/srep37261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han M, Zhang JC, Huang XF, Hashimoto K. Intake of 7,8-dihydroxyflavone from pregnancy to weaning prevents cognitive deficits in adult offspring after maternal immune activation. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;267:479–483. doi: 10.1007/s00406-017-0802-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lombardo, M. V. et al. Maternal immune activation dysregulation of the fetal brain transcriptome and relevance to the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry 2017 Mar 21. 10.1038/mp.2017.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Money KM, et al. Gestational diabetes exacerbates maternal immune activation effects in the developing brain. Mol Psychiatry 2017 Sep 26. 10.1038/mp.2017.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lewis DA, Curley AA, Glausier JR, Volk DW. Cortical parvalbumin interneurons and cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez-Burgos G, Cho RY, Lewis DA. Alterations in cortical network oscillations and parvalbumin neurons in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuijpers M, Hoogenraad CC. Centrosomes, microtubules and neuronal development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;48:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilmartin JV. Sfi1p has conserved centrin-binding sites and an essential function in budding yeast spindle pole body duplication. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:1211–1221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinez-Sanz J, Assairi L. New insights into the interaction of centrin with Sfi1. Biochim Biophy Acta. 2016;1864:319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang JC, et al. Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway confers resilience versus susceptibility to inescapable electric stress. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2017 Nov 8. 10.1007/s00406-017-0848-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Piontkewitz Y. Effects of risperidone treatment in adolescence on hippocampal neurogenesis, parvalbumin expression, and vascularization following prenatal immune activation in rats. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:353–363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khandaker GM, Zimbron J, Lewis G, Jones PB. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systemic review of population-based studies. Psychol Med. 2013;43:239–257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yao W, et al. Role of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling in depression and dietary intake of glucoraphanin confers stress resilience in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30659. doi: 10.1038/srep30659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang JC, et al. Prophylactic effects of sulforaphane on depression-like behavior and dendritic changes in mice after inflammation. J Nutri Biochem. 2017;39:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maekawa M, et al. Utility of scalp hair follicles as a novel source of biomarker genes for psychiatric illnesses. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishizuka K, Paek M, Kamiya A, Sawa A. A review of Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia-1 (DISC1): neurodevelopment, cognition, and mental condistions. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1189–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ye F, et al. DISC1 regulates neurogenesis via modulating kinetochore attachment of Ndel1/Nde1 during mitosis. Neuron. 2017;96:1041–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trent S, Fry JP, Ojarikre OA, Davies W. Altered brain gene expression but not steroid biochemistry in a genetic mouse model of neurodevelopmental disorder. Mol Autism. 2014;5:21. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van der Zwaag B, et al. Gene-network analysis identifies susceptibility genes related to glycobiology in autism. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenfeld JA, et al. Copy number variations associated with autism spectrum disorders contribute to a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders. Genet Med. 2010;12:694–702. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f0c5f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griswold AJ, et al. Evaluation of copy number variations reveals novel candidate genes in autism spectrum disorder-associated pathways. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3513–3523. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh K, et al. Sulforaphane treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:15550–15555. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416940111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Selemon LD, Zecevic N. Schizophrenia: a tale of two critical periods for prefrontal cortical development. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e623. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGrath JJ, Feron FP, Burne TH, Mackay-Sim A, Eyles DW. The neurodevelopmental hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review of recent developments. Ann Med. 2003;35:86–93. doi: 10.1080/07853890310010005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maekawa M, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acid deficiency during neurodevelopment in mice models the prodromal state of schizophrenia through epigenetic changes in nuclear receptor genes. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1229. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Torrey EF, Webster M, Knable M, Johnston N, Yolken RH. The Stanley Foundation Brain Collection and Neuropathology Consortium. Schizophr Res. 2000;44:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang, B., Ren, Q., Zhang, J. C., Chen, Q. X. & Hashimoto, K. Altered expression of BDNF, BDNF pro-peptide and their precursor proBDNF in brain and liver tissues from psychiatric disorders: rethinking the brain-liver axis. Tranl Psychiatry7, e1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]