Abstract

Isolated posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries are relatively rare and PCL injuries most commonly occur in the setting of multiligamentous knee injuries. PCL injuries can be treated with primary repair, which has the advantages of preserving the native tissue, maintaining proprioception, and minimal invasive surgery when compared with reconstruction surgery. Historically, primary repair of PCL injuries was performed in all tear types using an open approach, and, although the subjective outcomes were relatively good, patients often had residual laxity. Modern advances and increasing knowledge could improve the outcomes of PCL repair. With magnetic resonance imaging patients with proximal tears and sufficient tissue quality can be selected, and with arthroscopy and suture anchors minimal invasive surgery with direct fixation can be performed. Furthermore, with suture augmentation the healing of the repaired PCL can be protected and the residual laxity can be prevented. In this Technical Note, we describe the surgical technique of arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears with suture anchors and suture augmentation. The goal of arthroscopic primary repair is the preservation of the native PCL using a minimally invasive method and subsequent protection of this repair using suture augmentation.

Posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) injuries have been reported to occur in 1% to 40% of all acute knee injuries, of which most injuries (94% to 97%) occur in the setting of multiligamentous knee injuries.1 The treatment of PCL injuries these days depends on the location of the tear: proximal avulsion tears can be treated with arthroscopic primary repair,2, 3, 4 distal bony avulsion can be treated with internal fixation,5 whereas midsubstance tears are generally treated with PCL reconstruction.6

Historically, open primary repair was the preferred treatment of PCL injuries.7, 8, 9, 10 Despite the excellent subjective outcomes and return to recreational sports that has been reported after open primary PCL repair, it is often noted that a 1+ or 2+ posterior drawer is present postoperatively.7, 8, 9, 10 This can be explained by the gravity pulling the tibia posteriorly leading to increased stress on the repaired PCL and preventing optimal healing.9 These results of inadequately restoring tibial station and preventing posterior tibial translation led to a shift towards PCL reconstruction in patients with PCL injuries.1

With the modern advancements of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for better patient selection, arthroscopy for minimally morbid surgery, and suture anchors for direct fixation, a resurgence of interest has been noted in arthroscopic primary PCL repair.2, 3, 4 Also recently, a suture augmentation has been developed that prevents sagging of the tibia posteriorly, can protect the ligament during the healing process, and prevents attenuation of the repaired PCL.11 With these developments, there is a role for arthroscopic primary PCL repair with suture augmentation for patients with proximal tears. In this Technical Note, we describe the surgical technique of arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears with suture anchors and suture augmentation. The goal of arthroscopic primary repair is the preservation of the native PCL using a minimally invasive method and subsequent protection of this repair using suture augmentation.

Patient Selection

Arthroscopic primary PCL repair with suture augmentation can be performed in patients with proximal soft tissue avulsion tears and sufficient tissue quality. Although preoperative MRI can be used to assess the PCL tear location and the eligibility for primary repair, the final decision is always made during arthroscopy. Ligament remnants that can be reapproximated to the femoral wall and have sufficient tissue quality to withhold sutures will be treated with primary repair with suture augmentation, whereas ligament remnants with insufficient tissue length or tissue quality will be treated with PCL reconstruction. Patients of all ages and activity levels can be treated with this technique including pediatric patients and patients with multiligamentous injured knees. Surgeons should be aware of this type of injury because it is relatively common: 94% to 97% of all PCL injuries occur in multiligamentous injured knees1 and 46% of these PCL injuries have been described to be proximal avulsion type tears.12

Surgical Technique

General Preparation

The patient is placed in the supine position, and the operative leg is prepped and draped in a sterile fashion with a tourniquet around the thigh. Anteromedial and anterolateral portals are created, and a general inspection of the knee joint is performed. A malleable passport cannula (Arthrex, Naples, FL) is placed in the anteromedial portal for suture management. Using arthroscopy the ligament is inspected, and the tear location and tissue quality are assessed (Fig 1A, Video 1). The distal remnant of the PCL is then mobilized toward the femoral footprint using a grasper to assess if sufficient tissue length is present (Fig 1B). An anterior drawer force can be performed during the length assessment, because the tibia is sometimes subluxed posteriorly, which can lead to the false assessment that the distal remnant is too short for repair (Table 1).

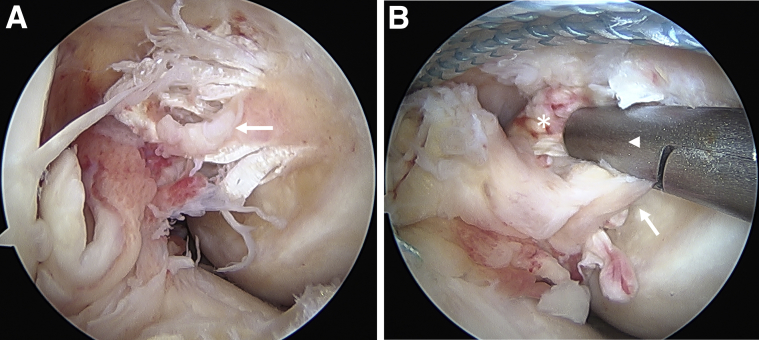

Fig 1.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is avulsed from the femoral insertion with only a few fibers remaining on the femoral wall (arrow). (B) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The PCL remnant (asterisk) is mobilized with a grasper (arrowhead) toward the femoral PCL footprint (arrow) to assess if sufficient tissue length is present. An anterior drawer force is usually performed to prevent false assessment of a too short ligament.

Table 1.

Surgical Pearls and Pitfalls of Arthroscopic Primary Posterior Cruciate Ligament Repair With Suture Augmentation

| Pearls | Pitfalls |

|---|---|

| Use MRI to identify proximal tears preoperatively | Increased resistance with the SuturePasser could indicate a previously placed stitch |

| Assess tissue quality for eligibility of primary repair | Not deploying the suture anchor deep enough at the tibia can cause hardware irritation |

| Use a cannula for better suture management | |

| Use an accessory portal for docking sutures | |

| Perform anterior drawer force to reduce the tibia to the anatomic position before anchor fixation | |

| Load the anterolateral suture anchor with a suture augmentation | |

| Use a posteromedial portal for direct visualization of the tibial PCL footprint |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament.

Suturing of Both PCL Bundles

First, the anterolateral and posteromedial bundles of the PCL are identified. Oftentimes, a single draw stitch is placed in the substance of the PCL using a self-retrieving SuturePasser (Arthrex) to place traction on the ligament and facilitate deeper bites. Then, a No. 2 FiberWire suture is passed through the anterolateral bundle starting distally as close to the tibial insertion as possible. Then the SuturePasser is reloaded, and each subsequent stitch is passed more proximally in the opposite direction, thus creating an alternating-interlocking Bunnell pattern toward the avulsed proximal end. Using multiple stitches will increase the pullout strength, and starting distally ensures that the sutures also rely on the distal part that has the best tissue quality. If resistance is experienced with a pass, the SuturePasser should be repositioned to avoid cutting of a previously placed suture. Then, the same process is repeated for the posteromedial bundle using No. 2 TigerWire sutures (Fig 2A). The sutures of both bundles are then guided outside the knee via an additional accessory portal just above the anteromedial portal. Although the sutures and the PCL are protected via the accessory portal, the femoral footprint is roughened with a burr or shaver.

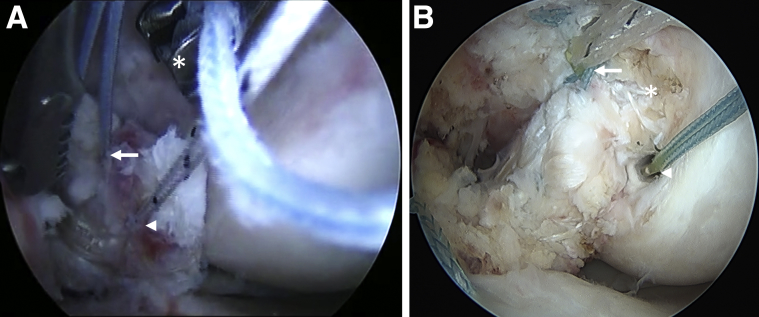

Fig 2.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. A suture passer (asterisk) is used to pass FiberWire sutures (arrow) to the posteromedial part of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). A TigerWire suture (arrowhead) is used to keep the PCL anteriorly and visible. (B) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The PCL is reapproximated toward the femoral PCL footprint (asterisk) using both the anterolateral (arrow) and posteromedial (arrowhead) suture anchors. The suture augmentation, consisting of TigerTape, exits the anterolateral suture anchor (arrow).

Suture Fixation

The arthroscope is now switched to the anteromedial portal to enable suture anchor management from the anterolateral portal, because this provides a better angle. With the knee at 90° of flexion, coming through the anterolateral portal, a suture hole is tapped, drilled, or punched (depending on the bone density) at the anterolateral origin of the PCL footprint. The sutures of the anterolateral bundle are then passed through the eyelet of a 4.75-mm Vented Biocomposite SwiveLock suture anchor, which is preloaded with a No. 2 FiberTape that will function as the suture augmentation. After an anterior drawer force is applied to restore the tibia to its anatomic position, the suture anchor is deployed and the anterolateral bundle is reapproximated to the footprint. Then, the same process is repeated for the posteromedial bundle using a suture anchor that is not preloaded with FiberTape. If a small gap exists between the PCL and the footprint, a core stitch from one of the suture anchors can be passed through the PCL from medial to lateral, and tied down with a Knot pusher (Arthrex) toward the femoral wall to compress the PCL back to the footprint (Fig 2B). After both bundles are reapproximated to the medial femoral condyle, the core stitches are removed, and the repair stitches are cut flush to the wall. The FiberTape is now docked via the accessory portal.

Suture Augmentation

For the distal fixation of the suture augmentation, a posteromedial portal is created under direct visualization using a spinal needle for localization. The arthroscope is then placed in the posteromedial portal. Although the tibial PCL footprint is visualized from posterior, a curved tibial guide is placed from the anteromedial portal down to the tibial PCL insertion. A cannulated drill is then used to drill up from the anteromedial cortex of the tibia to the tibial PCL footprint. The drill is retrieved, and a Micro SutureLasso (Arthrex) is passed up to the tibial PCL footprint. After the SutureLasso is retrieved through the anteromedial portal, the FiberTape is also retrieved through the anteromedial portal, and the FiberTape is passed through the SutureLasso. Then, the SutureLasso is retrieved distally through the knee joint and the tibial drill hole. The suture augmentation runs now from the anterolateral suture anchor down along the repaired PCL (Fig 3A) through the tibial and exits at the anteromedial tibial cortex. The FiberTape is tensioned, whereas an anterior drawer force is placed on the tibia with the knee at 90° of flexion, and fixed into the anteromedial tibial cortex using a 4.75-mm Vented Biocomposite suture anchor. The repair with suture augmentation is now complete (Fig 3B), and the knee stability is tested using the posterior drawer test.

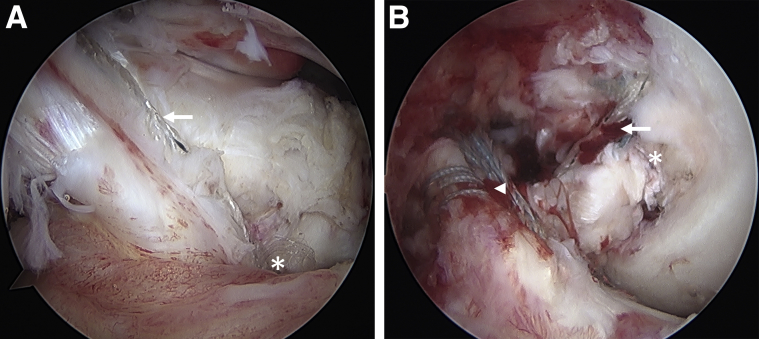

Fig 3.

(A) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the posteromedial portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The TigerTape suture augmentation (arrow) runs along the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) and runs through the tibial footprint of the PCL (asterisk) to the anteromedial tibial cortex. (B) Arthroscopic view of a right knee, viewed from the anterolateral portal with the patient supine and the knee in 90° flexion. The primary repair of the PCL is complete (asterisk) and the TigerTape suture augmentation runs along the PCL distally (arrow). In this patient, a primary repair of the anterior cruciate ligament with a suture augmentation (arrowhead) was also performed.

Rehabilitation

The main goals of rehabilitation are controlling edema and regaining range of motion (ROM), while preventing quadriceps atrophy. The exact rehabilitation program depends on the other ligamentous injuries, because PCL injuries most often occur with other ligamentous injuries. Generally, patients leave the operating room with a hinged knee brace locked in extension, which is worn for 4 weeks. If volitional quadriceps has returned, the brace can be unlocked for ambulation. Patients are allowed to weight bear as tolerated, again depending on the concomitant injury pattern, and can start ROM exercises the first day after surgery. Patients are advanced slowly to strengthening and a standard knee ligament protocol after 4 to 6 weeks, when also closed chain hamstring exercises are started. Muscle strength and ROM generally return quickly after the procedure, due to the minimal invasive nature of the surgery, and the preservation of the native tissue and proprioception. Gradual return to sports is generally indicated around 6 months postoperatively.

Discussion

In the 1980s and 1990s, several studies reported on outcomes of open primary PCL repair. It should be noted that it is difficult to review outcomes of PCL treatment due to the often heterogeneous populations with regard to concomitant injuries. Hughston et al.7 were the first to report on 29 patients undergoing primary PCL repair in 1980, of whom 55% had proximal tears. At minimum 5-year follow-up, they found that 90% of patients were scored subjectively as good, whereas 65% of patients were scored objectively as good. A few years later, in 1984, Strand et al.8 reported their outcomes of 32 PCL injuries at 4-year follow-up. They noted, despite good or excellent outcomes in 81% of patients, that 56% of patients had 1+ posterior drawer or more. Pournaras et al.9 reported on their outcomes of 20 patients treated with open primary repair in 1991, and they noted that all patients had a 1+ to 2+ posterior drawer sign postoperatively and a posterior tibial sag. They stated that “it seems that sutures alone are not strong enough to resist the forces applied on the repaired PCL, which ultimately fails and cannot provide static stability.”9

With the modern advances of MRI and arthroscopy, better patient selection (proximal tears), and less invasive surgery, studies in the 21st century have focused on outcomes of arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears. Wheatley et al.10 were the first to report on arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears in 11 patients, and reported excellent outcomes at 4-year follow-up with a mean Lysholm score of 95.4, and all patients returning to preinjury level of activity including 2 professional football athletes. However, they still noted that 6 patients (55%) had posterior translation of 3 to 5 mm on clinical examination. Recently, some technical studies have reported on using suture anchors for arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears, but studies reporting outcomes are lacking.2, 3, 4 With the outcomes in the open primary repair studies and in the study of Wheatley et al., it can, however, be expected that residual posterior stability remains after primary repair.

The advantages of primary repair compared with reconstruction are the preservation of native tissue and proprioception. Furthermore, the procedure is relatively quick, minimally invasive (no grafts are harvested or large tunnels are drilled), and recovery is dramatically faster due to the minimal invasive surgery and avoidance of quadriceps atrophy. The theoretical advantages of the suture augmentation technique are that the ligament is protected during the healing phase, and that the posterior drawer sign and posterior sagging of the tibia would not occur. The disadvantage of this technique is that it can only be performed in patients with proximal tears, and in the acute or subacute setting, because the tissue quality is generally not sufficient in the chronic stage (generally within 1 month) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Indications and Contraindications of Arthroscopic Primary Posterior Cruciate Ligament Repair With Suture Augmentation

| Indications | Absolute Contraindications |

| Proximal soft-tissue avulsion tear | Midsubstance tears |

| Good tissue quality | Poor tissue quality |

| Also in patients with open physes | Chronic tears in which tissue quality is insufficient or tissue is reabsorbed |

| Also in patients with multiligamentous injured knees | |

| Relative Contraindications | |

| Surgical experience | |

| Fair tissue quality |

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Arthroscopic Primary Posterior Cruciate Ligament Repair With Suture Augmentation

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Compared with PCL reconstruction | |

| Preservation of native tissue and proprioception | Only in patients with proximal tears and sufficient tissue quality |

| Quick procedure | Only in acute or subacute setting |

| No graft harvesting complications | |

| No large tunnels drilled | |

| No problems with future PCL reconstruction | |

| Faster recovery | |

| Prevention of quadriceps atrophy | |

| Physeal sparing approach in children | |

| No conflict with other tunnels in patients with concomitant ACL injury | |

| Compared with primary PCL repair without a suture augmentation | |

| Protection of ligament during healing phase | Surgeon should be able to perform posterior knee arthroscopy |

| No posterior sag or posterior tibial translation | Additional small incision over the tibial cortex |

ACL, anterior cruciate ligament; PCL, posterior cruciate ligament.

In conclusion, we present the surgical technique of arthroscopic primary repair of proximal PCL tears with suture augmentation. The advantages of this procedure are the minimal invasive nature of the procedure, quick recovery, and prevention of quadriceps atrophy. Furthermore, the native tissue and proprioception are preserved with primary PCL repair. Because historical results have shown that residual laxity often occurs after primary PCL repair, the suture augmentation is added to this technique to protect the ligament during the early phases of healing.

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: G.S.D. is a consultant for Arthrex; and has received grants from Arthrex. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Step-by-step surgical technique video of arthroscopic primary posterior cruciate ligament repair with suture augmentation. This is an arthroscopic video of a patient with a right knee injury in a supine position with the knee in 90° flexion. Most of the video is filmed from the anterolateral portal, although some parts are filmed from the anteromedial or posteromedial portal. The exact portal use is explained in the video before each section.

References

- 1.Fanelli G.C., Beck J.D., Edson C.J. Current concepts review: The posterior cruciate ligament. J Knee Surg. 2010;23:61–72. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1267466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiFelice G.S., van der List J.P. Arthroscopic primary repair of posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2015;23:307–314. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosso F., Bisicchia S., Amendola A. Arthroscopic repair of “peel-off” lesion of the posterior cruciate ligament at the femoral condyle. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3:e149–e154. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiFelice G.S., Lissy M., Haynes P. Surgical technique: When to arthroscopically repair the torn posterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:861–868. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2034-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen S.Y., Cheng C.Y., Chang S.S. Arthroscopic suture fixation for avulsion fractures in the tibial attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:1454–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.04.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LaPrade C.M., Civitarese D.M., Rasmussen M.T., LaPrade R.F. Emerging updates on the posterior cruciate ligament: A review of the current literature. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:3077–3092. doi: 10.1177/0363546515572770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughston J.C., Bowden J.A., Andrews J.R., Norwood L.A. Acute tears of the posterior cruciate ligament. Results of operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:438–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strand T., Molster A.O., Engesaeter L.B., Raugstad T.S., Alho A. Primary repair in posterior cruciate ligament injuries. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:545–547. doi: 10.3109/17453678408992956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pournaras J., Symeonides P.P. The results of surgical repair of acute tears of the posterior cruciate ligament. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;267:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheatley W.B., Martinez A.E., Sacks T. Arthroscopic posterior cruciate ligament repair. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:695–702. doi: 10.1053/jars.2002.32836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackay G.M., Blyth M.J., Anthony I., Hopper G.P., Ribbans W.J. A review of ligament augmentation with the InternalBrace: The surgical principle is described for the lateral ankle ligament and ACL repair in particular, and a comprehensive review of other surgical applications and techniques is presented. Surg Technol Int. 2015;26:239–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twaddle B.C., Bidwell T.A., Chapman J.R. Knee dislocations: Where are the lesions? A prospective evaluation of surgical findings in 63 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 2003;17:198–202. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Step-by-step surgical technique video of arthroscopic primary posterior cruciate ligament repair with suture augmentation. This is an arthroscopic video of a patient with a right knee injury in a supine position with the knee in 90° flexion. Most of the video is filmed from the anterolateral portal, although some parts are filmed from the anteromedial or posteromedial portal. The exact portal use is explained in the video before each section.