Abstract

The aim of this work was to study the genetic basis of the backfat expression of lipid-related genes associated with meat quality traits in pigs. We performed a genome-wide association study with the backfat gene expression measured in 44 genes by qPCR and the PorcineSNP60 BeadChip genotypes in 115 Iberian x Landrace backcross animals. A total of 193 expression-associated SNPs located in 19 chromosomal regions were associated with expression levels of ACSM5, ELOVL6, FABP4, FADS2, and SLC27A4 genes. Three expression quantitative trail loci (eQTLs) corresponding to ACSM5, FABP4, and FADS2 were classified as cis-acting eQTLs, whereas the remaining 16 eQTLs have trans-regulatory effects. Remarkably, a SNP in the ACSM5 promoter region and a SNP in the 3′UTR region of FABP4 were the most associated polymorphisms with the ACSM5 and FABP4 expression levels, respectively. Moreover, relevant lipid-related genes mapped in the trans-eQTLs regions associated with the ACSM5, FABP4, FADS2, and SLC27A4 genes. Interestingly, a trans-eQTL hotspot on SSC13 regulating the gene expression of ELOVL6, ELOLV5, and SCD, three important genes implicated in the elongation and desaturation of fatty acids, was identified. These findings provide new data to further understand the functional regulatory mechanisms implicated in the variation of fatty acid composition in pigs.

Introduction

Pork meat is an appreciated, all-purpose lean meat, and represents one of the main sources of animal meat for humans1. Fat and fatty acids (FAs), are fundamental to various aspects of meat quality and play a crucial role to meat nutritional value, both in adipose tissue (backfat, BF) and muscle (intramuscular fat2). It is demonstrated that FA composition is dependent on physiological status, nutrition conditions2,3, and genetic factors4.

In the last few years, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have been performed in attempts to uncover the genetic basis of FA composition traits. Studies of our group and others have benefited from this approach and have identified genomic regions significantly associated with intramuscular fatty acid (IMFA) composition by using different experimental and commercial populations5–9. However, in most cases, the GWAS approach only allows the detection of genetic variants that explain a modest proportion of the total heritability of the analyzed traits10. In addition, the way from the genomic statistical association to the identification of true causal genetic variants is plagued of difficulties. Hence, it has become evident the necessity to integrate new approaches to better understand the biological significance of GWAS findings. Recently, the association between genetic variants and gene expression levels has been described and used to identify expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs). The eQTLs regulating the transcript abundance of the mRNAs can be identified systematically using high-throughput technologies and have recently been proposed as a good strategy to deepen the study of the genetic architecture of complex traits11,12.

Liver, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue are three of the most important tissues involved in FA metabolism13. Adipose tissue, one of the main energy reserves in animals, is composed of adipocytes embedded in a matrix of connective tissue with a highly developed vascular system. The adipocytes are dynamic cells that play a relevant role in energy balance and overall body homeostasis. Their main metabolic functions are to accumulate lipids, by synthesis of triacylglycerols, and lipid mobilization, through hydrolysis of triacylglycerols14.

Previous studies in our group have identified genomic regions, candidate regulators and regulatory polymorphisms in the liver and muscle tissues of individuals of an Iberian x Landrace backcross population (BC1_LD15,16). Furthermore, a RNA-Seq transcriptome study of the adipose tissue of two groups of pigs with phenotypically extreme IMFA composition in the BC1_LD animals identified metabolic pathways differentially modulated between groups controlling lipid and FA metabolism17. Taking into account the relevant role of adipose tissue in the regulation of lipid metabolism, the goals of the present work were (1) to study the expression of candidate genes related with lipid metabolism in the adipose tissue of BC1_LD animals and (2) to analyze the chromosomal regions significantly associated with the gene expression levels to characterize the regulatory mechanisms influencing gene expression phenotypes. With these results we aim to increase our knowledge of the regulation of key genes determining FA composition in pigs in adipose tissue.

Results and Discussion

Selection of genes related with lipid metabolism in the adipose tissue

Using the information generated in previous studies of our group, strong candidate genes affecting FA composition of BF and intramuscular fat in the BC1_LD generation were identified by GWAS, RNA-Seq and co-association network approaches5,17–21 (Supplementary Table S1). A total of 44 candidate genes related with lipid metabolism were selected to study their expression pattern in BF. Fourteen of them (ARNT, CYP2U1, EGF, ELOVL6, FABP4, FABP5, FADS1, FADS2, FADS3, NFKB1, PLA2G12A, PLCB2, PLPP1, and USF1) are functional and positional candidate genes related with lipid metabolism which were identified in GWAS analyses for BF and IMFA composition in the BC1_LD animals5,21. We also included two candidate genes differentially-expressed (ELOVL6 and SCD) in a RNA-Seq analysis of the adipose tissue of two phenotypically extreme groups of animals for IMFA composition in the BC1_LD cross17. Lipid metabolism genes identified in gene co-association networks for FA composition (ACSM5, ANK2, ARNT, FABP4, FABP5, MGLL, and PPARG)19 were also included; two of which, ARNT and PPARG, were also identified in gene co-association networks for fatness and growth traits20. In addition, in order to complete the set of genes, we included genes which have been described in the literature to play different roles in lipid metabolism such as transporters (RBP4, SCAP, SLC27A1, and SLC27A4), enzymes (AGPAT2, CPT1A, CROT, DGAT1, DGAT2, ELOVL5, LIPC, LPIN1, PEX2, and PNPLA2) and transcriptional factors, cofactors or nuclear receptors (CD36, ESRRA, MLXIPL, NR1H3, POU2F1, PPARA, PPARD, PPARGC1A, RXRG, and SREBF1). Finally, we added the ADIPOQ gene, which encodes an important adipokine of white fat tissue, exerting multiple biological processes on carbohydrate and lipid metabolism (review in Shehzad et al.22). Although this gene is not annotated in the current Sscrofa10.2 assembly, it has been mapped to the SSC13q36-41 interval23.

Four reference genes (ACTB, B2M, HPRT, and TBP) were also selected as reference controls.

Expression genome-wide association analysis

In the present study, the adipose tissue expression of 48 genes (44 target and four reference genes) was measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) in 115 BC1_LD animals. For the PPARGC1A gene, a poor PCR efficiency was obtained and it was discarded for further analysis. Expression GWAS (eGWAS) were performed with the gene expression values of the 43 remaining target genes and the genotypes of 40,460 SNPs of the PorcineSNP60 BeadChip (Illumina) that passed the quality control (see Methods section).

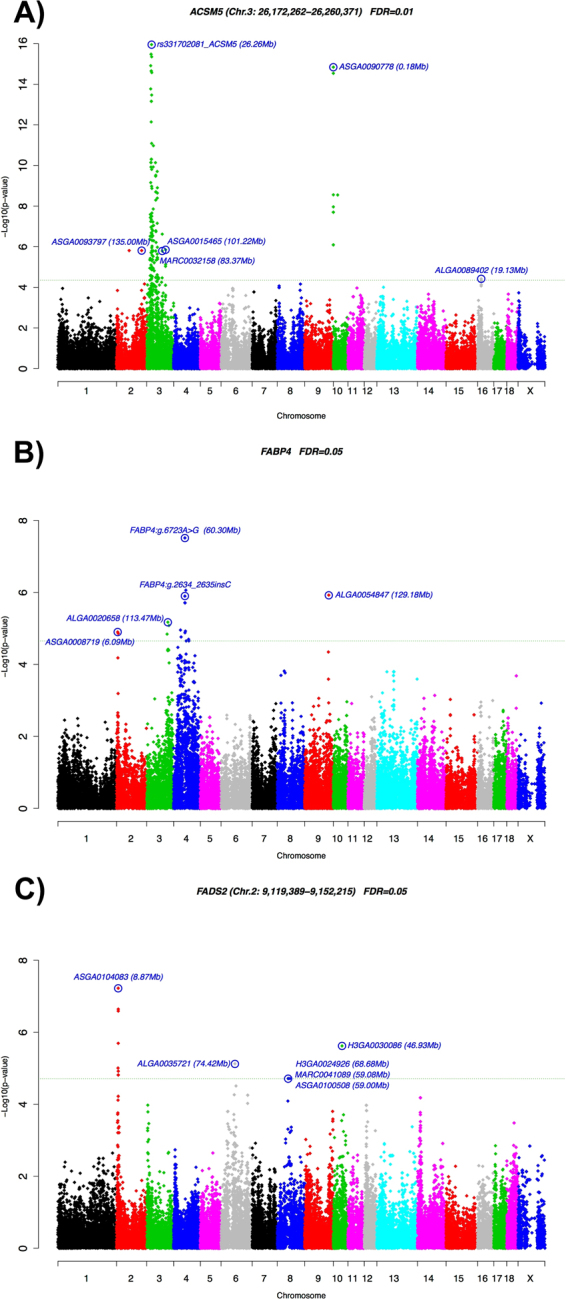

At whole genome level (q-value ≤ 0.05), significant association signals in five of the analyzed genes were detected (Table 1, Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1): ACSM5, ELOVL6, FABP4, FADS2, and SLC27A4. The ACSM5, FABP4, FADS2, and SLC27A4 genes presented more than one associated eQTL (Table 1). Three out of 19 eQTLs were identified as cis-acting for the ACSM5, FABP4, and FADS2 gene expression (Fig. 1), suggesting the presence of proximal polymorphisms regulating the expression of these genes. These results showed a difference in the ratio of cis- and trans-eQTLs. In general, studies performed in animals have identified regulatory trans-eQTLs in a higher ratio than those performed in humans12,24. Accordingly, previously eGWAS analyses performed in muscle15 and liver16 of BC1_LD animals identified a prevalence of porcine trans-eQTLs compared wih cis-eQTLs.

Figure 1.

GWAS plot of ACSM5, FABP4, and FADS2 gene expression in adipose tissue. The X-axis represents chromosome positions in Mb relative to Sscrofa10.2 assembly of the pig genome and the Y-axis shows the –log10 (p-value). Horizontal dashed lines indicate the genome-wide significance level. Plot of eGWAS for (A) ACSM5, (B) FABP4, and (C) FADS2 gene expression in backfat.

Table 1.

Significant eQTL identified.

| Interval | Chr | Position Mb Start-Enda,b | Size (Mb) | SNP Start | SNP End | No. SNPsc | Associated Gene | Type of eQTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | 2 | 134.99 | ASGA0093797 | 1 | ACSM5 | trans | ||

| I2 | 3 | 16.47–63.25 | 46.78 | ASGA0089930 | ALGA0111911 | 133 | ACSM5 | cis/trans |

| I3 | 3 | 83.37 | MARC0032158 | 1 | ACSM5 | trans | ||

| I4 | 3 | 100.91–101.46 | 0.55 | ALGA0020206 | ASGA0098441 | 3 | ACSM5 | trans |

| I5 | 10 | 0.05–0.20 | 0.15 | H3GA0055101 | ASGA0095156 | 8 | ACSM5 | trans |

| I6 | 16 | 19.13 | ALGA0089402 | 1 | ACSM5 | trans | ||

| I7 | 13 | 6.89 | ASGA0055780 | 1 | ELOVL6 | trans | ||

| I8 | 2 | 6.10–9.00 | 2.90 | ASGA0008719 | MARC0018949 | 2 | FABP4 | trans |

| I9 | 3 | 109.40–119.74 | 10.34 | ASGA0015643 | ASGA0016181 | 3 | FABP4 | trans |

| I10 | 4 | 36.73 | ALGA0024527 | 1 | FABP4 | trans | ||

| I11 | 4 | 60.57–65.25 | 4.68 | ALGA0025158 | ALGA0025337 | 5 | FABP4 | cis (FABP5)d |

| I12 | 9 | 129.18 | ALGA0054847 | 1 | FABP4 | trans | ||

| I13 | 2 | 7.85–9.22 | 1.37 | ASGA0008845 | ASGA0008874 | 8 | FADS2 | cis |

| I14 | 6 | 74.42 | ALGA0035721 | 1 | FADS2 | trans | ||

| I15 | 8 | 59.00–68.68 | 9.68 | ASGA0100508 | H3GA0024926 | 3 | FADS2 | trans |

| I16 | 10 | 46.93 | H3GA0030086 | 1 | FADS2 | trans | ||

| I17 | 9 | 20.18–20.20 | 0.02 | MARC0034587 | ASGA0041925 | 2 | SLC27A4 | trans |

| I18 | 14 | 88.90–92.43 | 3.53 | ASGA0064787 | ALGA0079407 | 16 | SLC27A4 | trans |

| I19 | 15 | 137.05–137.37 | 0.32 | ASGA0070790 | MARC0050960 | 2 | SLC27A4 | trans |

aChromosomal location is given according to Sscrofa10.2 assembly coordinates.

bGene annotation was performed including one additional Mb at the start and at the end of the trans eQTL regions. For the cis eQTLs only the analyzed gene was considered.

cNumber of significant SNPs within the eQTL interval.

dThe known mapped FABP5 gene (SSC4: 60.31 Mb) was used in order to define cis/trans eQTLs for the unmapped FABP4 gene.

The eGWAS identified 193 expression-associated SNPs located in 19 chromosomal regions on pig chromosomes SSC2-SSC4, SSC6, SSC8-SSC10 and SSC13-SSC16 (Table 1).

From the associated SNPs, and according to the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) of Ensembl (Sscrofa10.2 annotation release 84), 49.2% (95 SNPs) were located in intergenic regions. The remaining 50.8% (98 SNPs) mapped within a total of 68 genes: 66 in introns, 11 in 5′ upstream and 16 in 3′ downstream gene regions, three in the 3′UTR region, and two in the coding region of a gene determining synonymous mutations (Supplementary Table S2). A total of 86 SNPs (44.6%) were located inside the cis-acting eQTLs, whereas 107 SNPs (55.4%) were in trans-eQTLs (Supplementary Table S2).

In the following sections, the SNPs and genes mapped in the eQTL regions associated with the expression phenotypes of ACSM5, ELOVL6, FABP4, FADS2, and SLC27A4 are discussed in detail. The selection of genes in the eQTLs was performed by: (1) extracting the annotated genes from the eQTL intervals including an additional Mb at each end, (2) selecting genes with a lipid-related function and (3) expressed in adipose tissue. Table 2 summarizes all the relevant lipid-related genes mapped in the trans-eQTL regions.

Table 2.

Candidate genes annotated in trans-eQTLs related with lipid metabolism functions.

| Gene | Chr | Interval | Candidate gene within eQTL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACSM5 | 2 | I1 | ALDH7A1, MARCH3 |

| 3 | I3 | MDH1 | |

| 3 | I4 | PIGF, PRKCE | |

| 10 | I5 | COG7, GGA2, NDUFAB1 | |

| FABP4 | 2 | I8 | BSCL2, DAGLA, EHD1, FADS1, FADS2, FADS3, LGALS12, PLA2G16, SF1, TM7SF2 |

| 3 | I9 | CYP1B1, EHD3, EPT1, GALNT14, GCKR, HADHA, HADHB, LCLAT1, PLB1, PPP1CB, RBKS, SNX17, SPAST | |

| 9 | I12 | RFWD2 | |

| FADS2 | 6 | I14 | CDC42, ECE1, FUCA1, GALE, HMGCL, KDM1A |

| 8 | I15 | IGFBP7 | |

| 10 | I16 | CUBN | |

| SLC27A4 | 9 | I17 | PRCP |

| 15 | I19 | FARSB, MOGAT1 |

The ACSM5 gene

The most significant cis-SNPs (p-value = 1.11 × 10−17) for the Acyl-CoA Synthetase Medium-Chain Family Member 5 (ACSM5) gene expression were located between 23.44 Mb and 27.94 Mb on SSC3, covering a total of 25 SNPs (Supplementary Table S2), in a region where these SNPs have a high linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 = 0.42–0.99). Recently, the polymorphism ACSM5:g.26260422 G>A (rs331702081), located at the proximal promoter region of the ACSM5 gene, has been described as the most associated with the expression of ACSM5 in Longissimus dorsi muscle of BC1_LD animals15. Hence, the ACSM5:g.26260422 G>A SNP was genotyped in the 115 BC1_LD animals and included in the eGWAS study, showing that is one of the SNPs located in the 23.44–27.94 Mb block with the lowest p-value (p-value = 1.11 × 10−17; Fig. 1A). Consequently, this SNP may be a strong candidate to explain the mRNA variation of the ACSM5 gene in BF and muscle. Even so, the correlation value between the ACSM5 gene expression in BF and muscle is of r = 0.60 (p-value = 3.0 × 10−12), suggesting that other factors than the SSC3 cis-eQTL may be differentially regulating the expression of ACSM5 in both tissues.

The effect of ACSM5:g.26260422 G>A SNP on the binding of transcription factors (TFs) was determined by the LASAGNA-Search version 2.0 software25. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT) gene (TF ID = M00236 and M00539) and the signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) gene (TF ID = M00500) were identified to bind only when the A allele is present. ARNT gene plays an important role in the regulation of hepatic lipogenesis and gluconeogenesis26,27, and was identified as one of the most central genes in a liver co-expression network analysis of IMFA composition in pigs19. STAT6 gene has been described to interact with the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma gene (PPARG), and the cooperative binding of the two genes led to an increase response of PPARG28. The importance of PPARG gene lies on its regulation of adipocyte differentiation and glucose homeostasis, and it was identified as a major regulator for growth and fatness related traits in a co-association network in muscle of BC1_LD individuals20. Different transcription binding sites for PPARG in the ACSM5 proximal promoter region were also predicted by LASAGNA (Supplementary Table S3).

Five chromosomal regions (Table 1) were also associated in trans with the ACSM5 gene expression. Likewise, two of these regions on SSC3 (100.91–101.46 Mb) and SSC10 (0.05–0.20 Mb) have been recently associated with the mRNA expression of the ACSM5 gene in the Longissimus dorsi muscle of BC1_LD animals (SSC3: 100.35 Mb; SSC10: 0.17 Mb)15. These results, together with the cis-eQTL identification for the ACSM5 expression, further confirm the existence of common regulatory mechanisms implicated in the expression of ACSM5 in BF and muscle. No strong candidate genes exerting a known lipid metabolism function were detected in the trans-eQTL identified on SSC16 for ACSM5. Conversely, a list of lipid-related genes identified on SSC2, SSC3 and SSC10 ACSM5-trans associated regions is showed in Table 2.

The ELOVL6 gene

In the present study, previously described ELOVL6 polymorphisms (three in the promoter region, one in exon 4 and two in the 3′UTR region)18,29 were genotyped in the 115 BC1_LD animals and incorporated in the eGWAS. The obtained results were consistent with our previous studies on SSC818, showing a chromosome level significant region associated with ELOVL6 mRNA expression in BF (Supplementary Fig. S2). The most significant peak was for two SNPs with the same p-value (ALGA0049135 and ALGA0049139; p-value = 4.60 × 10−5; â = 0.563), located in an intron of ANK2, at 2.4 Mb to the ELOVL6 gene. In contrast the ELOVL6:c.-533C>T and ELOVL6:c.-394G>A polymorphisms, which were in full LD and also showed high association (p-value = 6.42 × 10−04; â = 0.460), did not achieve statistical significance after multiple testing corrections (q-value ≤ 0.05; Supplementary Fig. S2). This observed discrepancy could be due to the different animals used between the two studies (94 samples overlapping between the two studies) and to the subtle differences observed between the two methods used for mRNA quantification (Pearson correlation coefficient, r = 0.91).

Interestingly, ANK2 is one of the most central genes in an adipose co-expression network related with IMFA composition in the BC1_LD19. In a recent study, knockin mice expressing ANK2 genes with human nonsynonymous mutations showed altered glucose homeostasis contributing to increased adiposity. This phenotype was caused by the reduction in ANK2 protein levels which produce an elevation of cell surface GLUT4 and increased glucose uptake in skeletal muscle and fat30. Thus, we cannot discard an association of this gene with the mRNA expression levels of ELOVL6. Further analyses are necessary to corroborate this hypothesis.

Regarding the trans-associated regions with the BF mRNA ELOVL6 expression, Corominas et al.18 did not identify any region at whole genome level (q-value ≤ 0.05), in contrast with the trans-eQTL on SSC13 identified in the present study. No genes related to lipid metabolism function were identified in the SSC13 trans-eQTL. However, we have to highlight that the same region on SSC13 was associated at chromosome level with the expression of the ELOVL5 and SCD genes. ELOVLs and SCD genes are implicated in the elongation and desaturation of FAs in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane. These metabolic functions are essential to the maintenance of lipid homeostasis (reviewed in Guillou et al.31). Moreover, it has been reported that the expression of these genes are primarily regulated at transcriptional level (reviewed in Guillou et al.31). In this study, highly significant Pearson’s correlations (p-value = 2.22 × 10−16) among the mRNA expression of these genes were obtained (rELOVL5-ELOVL6 = 0.90; rELOVL5-SCD = 0.84; rELOVL6-SCD = 0.86), supporting the involvement of common elements regulating their mRNA expression. In addition, we found high correlations with the genes coding for the TFs SREBF1 and PPARs (rELOVL5-PPARG = 0.75, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rELOVL5-SREBF1 = 0.74, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rELOVL5-PPARA = 0.65, p-value = 1.02 × 10−14; rELOVL6-PPARG = 0.68, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rELOVL6-SREBF1 = 0.70, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rELOVL6-PPARA = 0.69, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rSCD-PPARG = 0.59, p-value = 1.01 × 10−11; rSCD-SREBF1 = 0.63, p-value = 8.48 × 10−14; rSCD-PPARA = 0.51, p-value = 1.03 × 10−8) which contribute to the regulation of these genes17,31,32. High correlation values were also found between the mRNA expression of DGAT1 and DAGT2 genes with ELOVLs and SCD genes (rDGAT1-ELOVL5 = 0.72, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rDGAT1-ELOVL6 = 0.70, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rDGAT1-SCD = 0.59, p-value = 3.89 × 10−12; rDGAT2-ELOVL5 = 0.81, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rDGAT2-ELOVL6 = 0.74, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16; rDGAT2-SCD = 0.76, p-value = 2.22 × 10−16). This result agrees with the interrelated function of these genes which are implicated in lipogenesis (ELOVLs and SCD) and triglyceride (TG) synthesis (DGAT1 and DGAT2), the main function of adipose tissue14.

ELOVL6 and SCD genes were over-expressed in the adipose tissue transcriptome (RNA-Seq) of BC1_LD animals with higher content of intramuscular monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and saturated fatty acids (SFA), when compared with animals having more polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA)17 supporting the relevance of these genes in the determination of FA composition in the BC1_LD.

The FABP4 gene

The Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4 (FABP4) gene is not annotated in the current Sscrofa10.2 assembly. Nevertheless, radiation hybrid (RH) and linkage maps located FABP4 gene close to FABP5 on SSC433,34, in agreement with the human comparative map. For this reason, we used the position of the annotated FABP5 gene (SSC4: 60.31 Mb) in order to define cis/trans eQTLs for FABP4 gene. Recently, an indel located in the intron 1 of FABP4 (FABP4:g.2634_2635insC) was identified as the most associated polymorphism with the FABP4 mRNA levels in BF35. In the present study, this indel, which was genotyped in the 115 BC1_LD animals and included in the eGWAS study, was one of the most significant associated polymorphisms (p-value = 1. 27 × 10−6; â = −0.219) (Fig. 1B), but the most significant cis-SNP (ALGA0025337; p-value = 8.67 × 10−7; â = 0.328) was located in an intergenic region (Supplementary Table S2).

Taking into account the highly polymorphic nature of the porcine FABP4 gene36 and a possible regulatory role of miRNAs in the FABP4 gene expression37, the 3′UTR of the FABP4 gene was amplified and sequenced using 10 animals with extreme values of FABP4 mRNA expression in BF. A polymorphism in the 3′UTR (FABP4:g.6723 A>G) was identified and genotyped in the 115 BC1_LD animals. The association analysis with the FABP4 mRNA expression values revealed that the SNP in the 3′UTR region has the lowest p-value (p-value = 3.07 × 10−8; â = −0.260) (Fig. 1B).

Interestingly, FABP4:g.6723 A>G SNP was inside a putative miRNA binding site for the putative human miRNA hsa-miR-3182 and it is predicted to bind only when FABP4:g.6723 G allele is present. However, we did not find the homologous Sus scrofa miR-3182 in the current assembly (Sscrofa10.2) of the pig genome. Although the 3′UTR SNP (FABP4:g.6723 A>G) is a clear candidate to explain the differences of FABP4 mRNA levels among animals, we cannot discard also a role of the indel (FABP4:g.2634_2635insC) in the FABP4 gene regulation. Indeed, the indel polymorphism was predicted to be located in a target binding site for PPARG and NR4A2 TFs35. In our analysis the correlation between the mRNA expression of PPARG and FABP4 was r = 0.51 (p-value = 9.27 × 10−9). Further functional analyses are needed to test the role of these polymorphisms in the FABP4 gene regulation and besides in the determination of IMFA composition.

The eGWAS performed for the FABP4 gene also revealed four trans-eQTLs on SSC2, SSC3, SSC4, and SSC9 (Table 1); where several genes involved in lipid metabolism were mapped (Table 2).

It is noteworthy to highlight some genes identified in the trans-eQTLs, such as the Berardinelli-Seip Congenital Lipodystrophy 2 (Seipin) (BSCL2) gene located on SSC2. Although the function of this gene is still being investigated, its relationship with adipogenesis, with the genesis of lipid droplets and the regulation of the metabolism of phospholipids and triacylglycerides has been established38. Liu et al.39 performed an adipose-specific Seipin knockout mice with FABP-mediated BSCL2 deletion exhibiting decreased lipolysis in response to β-adrenergic receptors agonists in vivo. In this chromosomal region we also identified the Lectin Galactoside Binding Soluble 12 (LGALS12) gene, an intracellular galectin preferentially expressed in adipocytes which regulates lipolysis and whole-body energy metabolism40. Furthermore, FABP4 and LGALS12 genes were identified in the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway in an expression analysis performed in human adipose-derived stem cells41. Finally, the Phospholipase A2 Group XVI (PLA2G16) gene, which encodes the most abundant PLA2 in the adipose tissue42, was also identified on SSC2. PLA2G16 has been described an important regulator of the rate of adipose tissue lipolysis via the production of eicosanoid mediators42. On SSC3, we identified the Cytochrome P450 Family 1 Subfamily B Member 1 (CYP1B1) gene. Liu et al.43 have demonstrated that the reduction in body weight gain and white adipose tissue in CYP1B1 deficient mice exhibited coordinated decreases in FA synthesis (regulated by FABP4, among others) when compared with wild type ones.

The FADS2 gene

The most significant cis-SNP for FADS2 gene expression (ASGA0104083; p-value = 5.98 × 10−8; â = 0.466) was located less than 0.23 Mb upstream of the FADS2 gene (Fig. 1C). FADS2 cluster together with FADS1 and FADS3 in a region on SSC244. In liver, a high correlation between the mRNA expression levels of FADS1 and FADS2 has been observed (rFADS1-FADS2 = 0.92; p-value = 1.11 × 10−17) and a common trans-associated chromosomal region was identified on SSCX16. Hence, these results pointed to common regulatory mechanisms controlling the mRNA expression of both desaturases in liver16. Conversely, in BF the correlation between the mRNA expression levels of FADS1 and FADS2 was lower (rFADS1-FADS2 = 0.63; p-value = 8.26 × 10−14) and only the cis-acting element associated with the FADS2 mRNA expression was identified. Altogether these results suggest that common and specific elements are regulating the expression of desaturases in BF.

Conversely, the low correlation observed between FADS2 mRNA levels in BF and liver (r = 0.23; p-value = 1.91 × 10−2) suggests a different mechanism of regulation in both tissues. In addition, the FADS2 gene was differentially-expressed between sexes depending on the tissue. Whereas in adipose tissue the FADS2 gene showed a higher expression in males, in liver the expression was higher in females16. Similar results have also been shown in rats, where the mRNA expression of FADS2 is higher in the liver of females than males45. To find polymorphisms which may modulate FADS2 expression a search of polymorphisms was performed by the analysis of whole-genome sequence data from seven founders of the IBMAP population with IGV46. Three polymorphisms were identified at positions g9118843C>T (rs331050552), g9118813G>A (rs321384923), and g9118721G>A (rs336076510) according to the Ensembl ENSSSCG00000013072 sequence. The most proximal 5′ mutation (g9118843C>T) was genotyped in the BC1_LD animals and included in the eGWAS analysis. However, no significant association was found between this mutation and the FADS2 mRNA expression. Further analyses are necessary to find new candidate cis-acting polymorphisms implicated in the regulation of FADS2 gene expression.

Three regions on SSC6, SSC8, and SSC10 were associated in trans with FADS2 gene expression where several lipid-related genes were identified (Table 2), highlighting the Lysine Demethylase 1A (KDM1A) gene, also known as LSD1, located on SSC6. This gene has been recently identified as a novel regulator of lipid metabolism as it is required for the expression of SREBF1 and for the efficient binding of SREBF1 to their target gene promoters47. Remarkably, SREBF1 regulates the expression of desaturases48, suggesting the KDM1A gene as a potential candidate regulator of FADS2 gene expression. Supporting this hypothesis, a transcription binding site for SREBF1 in the FADS2 proximal promoter region was predicted by LASAGNA (Supplementary Table S4).

The most associated SNP for FADS2 trans-eQTL on SSC8 was an intronic polymorphism (MARC0041089; p-value = 1.93 × 10−5; â = 0.516) in the Insulin Like Growth Factor Binding Protein 7 (IGFBP7) gene (Supplementary Table S2). This gene encodes a member of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein and through their regulation of IGFs and insulin may influence the metabolism of adipocytes, having implications in the development of obesity and insulin resistance49.

The SLC27A4 gene

The SLC27A4 (Solute Carrier Family 27 (Fatty Acid Transporter), Member 4) gene expression GWAS revealed three trans-eQTL on SSC9, SSC14, and SSC15 (Supplementary Fig. S1B). On SSC9, the Prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP) gene was located. It is an important regulator of energy and glucose homeostasis50. For the SSC14 trans-eQTL, no strong candidate genes related to lipid metabolism could be detected. Finally, on SSC15, Phenylalanyl-tRNA Synthetase Beta Subunit (FARSB) and Monoacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1 (MOGAT1) lipid-related genes were also identified.

Sex effect on gene expression in the adipose tissue

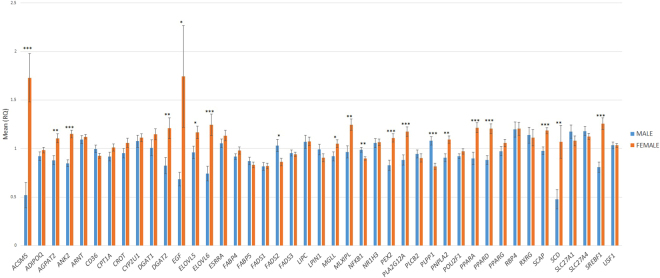

The control of FA homeostasis has been described to have a pronounced sexual dimorphism51. In agreement, sex differences in the control of gene expression have been identified in different tissues like muscle, liver, adipose tissue and brain in mice52,53. In the present work, a significant sex effect (p-value ≤ 0.05) on gene expression levels was detected in 20 out of the 43 genes analyzed (47%): ACSM5, AGPAT2, ANK2, ATGL, DGAT2, EGF, ELOVL5, ELOVL6, FADS2, MGLL, MLXIPL, NFKB1, PEX2, PLA2G12A, PLPP1, PPARA, PPARD, SCAP, SCD, and SREBF1 (Fig. 2). Overall, a higher number of genes were more expressed in females. Conversely, only three genes (FADS2, NFKB1, and PLPP1) showed a higher expression in males (Supplementary Table S6). Among them, some key regulators of lipid metabolism such as PPARA, SCD, and SREBF1 which may be determining the bias observed in the female over-expressed genes. In accordance, lipogenic genes such as SCD and SREBF1 were also more expressed in females in the Longissimus dorsi muscle15 and liver16 of pigs. However, we observed a different pattern of expression for PPARA, showing a higher expression level in females in liver and adipose tissue and a higher expression in males in muscle15,16. Finally, for ACSM5, AGPAT2, MLXIPL, EGF, ELOVL5, PEX2, and SCAP the same female-biased gene expression as in pig liver tissue16 was observed. This agree with the results observed in mice, in which the analysis of genes differentially expressed between sexes in liver, adipose, muscle, and brain revealed common functionalities of steroid and lipid metabolism among the sexually dimorphic genes between liver and adipose tissues. Furthermore, the overlap of sexually dimorphic genes was higher between adipose and liver tissues (22.9%) than between adipose and muscle tissues (6.6%;52). The highest rate of coincidence of female-biased gene expression among liver and adipose tissue may suggest common regulatory mechanisms in both tissues associated with sex differences.

Figure 2.

Comparison between males and females of gene expression levels of 43 lipid-related genes in adipose tissue. Data represent means ± standard error of the means (SEM). Significant differences between sexes are indicated as *p-value ≤ 0.05, **p-value ≤ 0.01 and ***p-value ≤ 0.001.

Fatty acid composition and gene expression in the adipose tissue

To explore the relationship between gene expression levels and FA composition percentages in BF and muscle, Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed. In general moderate correlations were identified for BF (Supplementary Fig. S3) and muscle (Supplementary Fig. S4).

For the FA composition percentages in BF, the CD36 gene, which may function as a regulator of FA transport54, showed a negative correlation with palmitoleic acid (C16:1(n-7)) (r = −0.31; p-value = 9.04 × 10−4). Palmitoleic acid (C16:1(n-7)) has been identified as a lipokine involved in the maintenance of systemic metabolic homeostasis55. In addition, a negative correlation between PLPP1 gene expression and palmitic acid (C16:0) (r = −0.35; p-value = 1.46 × 10−4) was found. This gene is a member of the phosphatidic acid phosphatase (PAP) family and participates in the synthesis of glycerolipids. Moreover, PLPP1 gene expression showed moderate correlations with the percentage of cis-7 hexadecenoic (C16:1(n-9)) (r = 0.32; p-value = 5.40 × 10−4) and C20:3(n-9) (r = 0.33; p-value = 3.40 × 10−4) FAs.

The cis-7 hexadecenoic acid (C16:1(n-9)) also showed negative correlation (r = −0.39; p-value = 2.05 × 10−5) with SCD gene expression, which plays an important role in the regulation of the expression of genes involved in lipogenesis56. In accordance, Fernández et al.57 have reported that SCD haplotypes, constituted by SCDg.2108 C>T, g.2228 T>C and G.2520 G>A, are associated with SCD gene expression in backfat and the fatty acid desaturation ratio in backfat and intramuscular fat in a Iberian x Duroc backcross.

Furthermore, the octadecenoic acid (C18:1(n-7)) was negatively correlated with CROT (r = −0.36; p-value = 1.02 × 10−4) and USF1 (r = −0.35; p-value = 1.29 × 10−4) gene expressions. The CROT gene plays a role in the pathway of FA beta-oxidation, and provides a crucial step in the transport of medium and long-chain acyl-coA out of the mammalian peroxisome to the mitochondria58. Moreover, USF1 gene is involved in the maintenance of high levels of FA synthase transcription under lipogenic conditions59.

For the FA composition percentages in muscle, PLPP1 mRNA expression was moderately correlated with the percentage of α-linolenic acid (C18:3(n-3)) (r = 0.39; p-value = 2.18 × 10−5), the double bond index (DBI) (r = 0.31; p-value = 7.69 × 10−4), the unsaturation index (UI) (r = 0.35; p-value = 1.33 × 10−4), and the ratio PUFA/SFA (r = 0.31; p-value = 8.76 × 10−4). Negative correlations were also identified with palmitic acid (C16:0) (r = −0.39; p-value = 1.56 × 10−5). The great variability between the PLPP1 gene expression and many FA composition percentages may be explained by its multiple functions, PLPP1 converts phosphatidic acid to diacylglycerol, and function in de novo synthesis of glycerolipids as well as in receptor activated signal transduction mediated by phospholipase D60. Furthermore, this gene has been described as a catabolic enzyme for lysophosphatidic acid61, and has been identified in the enriched functional category from the lipid catabolic process as a highly expressed gene in a transcriptome analysis of Basque pigs62.

Functional network analysis of genes mapping into eQTLs

To take a deep look at the regulatory mechanisms that are influencing the gene expression phenotypes, gene annotation of the 19 eQTLs chromosomal regions was performed. For trans-eQTLs all the genes located within ±1 Mb were selected for gene annotation. Conversely, for cis-eQTLs only the studied candidate gene was considered for further analyses. In the 19 eQTLs, a total of 474 protein-coding genes, 2 processed transcripts, 11 miRNAs, 3 miscRNAs, 10 pseudogenes, 6 rRNAs, 17 snoRNAs, and 21 snRNAs were annotated (Supplementary Table S5). From the 474 protein-coding genes with Ensembl Gene ID, 393 have at least one human orthologous gene (Supplementary Table S7) and were submitted to the Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (IPA, Ingenuity Systems Inc.) to perform a functional categorization.

Several networks related to lipid metabolism were identified: (i) lipid metabolism, small molecule biochemistry, infectious diseases (score = 42; interval = 8); (ii) lipid metabolism, small molecule biochemistry, cellular assembly and organization (score = 32; interval = 8); (iii) carbohydrate metabolism, organ morphology, reproductive system development and function (score = 30; interval = 3), and (iv) amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, molecular transport (score = 18; interval = 9) (Supplementary Table S8). Interestingly, two of the identified networks have the Akt complex as central (ID = 10 and 26; Supplementary Table S9). It is known that the PKB/Akt plays an important role in the insulin regulation of glucose transport63. In addition, it has been also identified as central in the main over-represented pathways in a muscle transcriptome study between individuals phenotypically extreme for IMFA composition64, in a muscle eQTL analysis of 45 lipid-related genes15, and in a liver eQTL analysis of 44 candidate genes related with lipid metabolism16. Remarkably, several of the potential regulators annotated in trans-eQTL for FABP4 and FADS2 (BSCL2, FADS1, FADS2, KDM1A, LGALS12, PLA2G16, PLB1, and PPP1CB) were identified inside the Akt pathway. These findings suggest this pathway as central in the genetic determination of FA composition traits in pigs.

Prediction analysis of transcription factor binding sites

To identify master regulators of global gene expression in all the genes analyzed in the present study, an in silico identification of the TF binding sites in the promoter region of (1) the 415 genes with human orthologous ID annotated in the trans-eQTL intervals and, (2) the 43 candidate lipid-related genes was performed using the iRegulon Cytoscape plugin65. The PPARG gene was the most enriched TF motif (normalized enrichment score, NES = 5.134; 167 target genes, 30 out of the 44 analyzed lipid-related candidate genes; Supplementary Table S9). This is in accordance with the fact that this gene is an adipogenic TF considered an important regulator of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism66. In our analysis the mRNA expression of PPARG was highly correlated with the mRNA expression of genes implicated in lipid transport, lipogenesis and TG synthesis (Supplementary Table S10), suggesting an important role of this TF in lipid storage. Interestingly, this TF has been identified as a key regulator of FA composition in the same animal material using a co-association network analysis19 and in a muscle eQTL analysis of 45 lipid-related genes15.

Conclusions

In the present study, potential candidate genes and genetic variants regulating the expression of lipid-related genes associated with meat quality traits in pigs have been identified by eGWAS analysis in the backfat adipose tissue of Iberian x Landrace backcrossed pigs. While some genetic variants identified in cis seem to be tissue specific (FADS2, FABP4), other may exert a similar regulatory control in different tissues (ACSM5). In addition to the well-known transcription factors SREBF1 and PPARs, that regulate the expression of lipogenic genes, a trans-eQTL on SSC13 identified for the ELOVL6 gene was associated with the expression of ELOVL5 and SCD genes, which are implicated in the elongation and desaturation of fatty acids, supporting the involvement of common elements regulating their mRNA expression in adipose tissue. These results increase our knowledge of the regulatory mechanisms implicated in adipose tissue lipid metabolism and its consequences in lipid-related traits.

Methods

Ethics Statement

All animal procedures were performed according to the Spanish Policy for Animal Protection RD1201/05, which meets the European Union Directive 86/609 about the protection of animals used in experimentation. Animals were sacrificed in a commercial slaughterhouse following national and institutional guidelines for the Good Experimental Practices and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Institution (IRTA- Institut de Recerca i Tecnologia Agroalimentàries).

Animal Samples

The IBMAP resource population was used in this study. This population was established by crossing 3 Iberian (Guadyerbas line) boars with 31 Landrace sows67, and 5 F1 males and 25 Landrace sows were crossed to obtain the BC1_LD generation (25% Iberian × 75% Landrace). The Iberian pig breed is characterized by high levels of IMF with higher MUFA and SFA content and an extremely fat body composition. In contrast, the Landrace breed has an efficient meat production, with low IMF and high PUFA content, and with a rapid growth and leaner carcass. Hence, the IBMAP experimental cross was generated to study the genetic basis of growth and meat quality traits differentiating the two breeds68. Here, we report results based on 115 BC1_LD pigs. All animals were maintained under intensive conditions and feeding was ad libitum with a cereal-based commercial diet. Backcross animals were slaughtered at an average age of 179.9 ± 8.9 days, and samples of BF tissue were collected, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Genomic DNA was extracted from diaphragm samples of all animals by the phenol-chloroform method69.

SNP Genotyping and quality control

A total of 115 animals belonging to BC1_LD were genotyped for 62,163 SNPs with the PorcineSNP60 Beadchip70 following the Infinium HD Assay Ultra protocol (Illumina Inc.; San Diego, USA). Raw data was visualized with GenomeStudio software (Illumina Inc.; San Diego, USA) and trimmed for high genotyping quality (call rate > 0.99). Plink software71 was used to remove markers that showed a minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 5% and SNPs with more than 5% of missing genotypes. The SNPs not mapped in the Sscrofa10.2 assembly were also excluded. After the quality control filter, a subset of 40,460 SNPs remained.

In addition, ten polymorphisms were genotyped in the BC1_LD animals: two SNPs located in the proximal promoter region of the ACSM5 (g.26260422 G>A, rs33170208115) and the FADS2 (rs331050552) genes, and one indel and one SNP located in the intron 1 (FABP4:g.2634_2635insC72) and in the 3′UTR region of the FABP4 gene (FABP4:g.6723 A>G), respectively. For the ELOVL6 gene, three SNPs located in the promoter region (ELOVL6:c.-533C>T, ELOVL6:c.-480C>T, and ELOVL6:c.-394G>A18,29), one in exon 4 (ELOVL6:c.416 C>T18) and two in the 3′UTR region (ELOVL6:c.1408 A>G and ELOVL6:c.1922C>T29) were genotyped. ACSM5 and FADS2 SNPs were genotyped using Taqman OpenArray™ genotyping plates designed in a QuantStudio™ 12 K flex Real-Time PCR System (ThermoFisher Scientific) using the SVGM platform (http://svgm.es/ca/Platforms/). The pyrosequencing protocol described by Mercadé et al.72 and the High Resolution Melting methodology (HRM, ThermoFisher Scientific) were used for genotyping the indel and the SNP of FABP4 gene, respectively. The SNPs belonging to ELOVL6 gene were genotyped using the KASP SNP genotyping service from LGC (http://www.lgcgroup.com/genotyping/).

Characterization of the 3′UTR of porcine FABP4 gene

The 3′UTR of the FABP4 gene was amplified and sequenced in 10 animals with extreme values of FABP4 mRNA expression in BF.

The 3′UTR variants of FABP4 gene were characterized by 3′-RACE PCR using UAP reverse primer and, FABP4-3NC-1-Fw and FABP4-3NC-2-Fw forward primers (Supplementary Table S11). The specific bands were excised from agarose gel and purified using NucleoSpin® Gel and PCR Clean-up (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG) and sequenced in forward and reverse directions.

All primers were designed using PRIMER3 software73 based on the Y16039 sequence33 and validated using PRIMER EXPRESS™ (Applied Biosystems). In all cases, PCR was performed in a 25 µl volume containing 2 µl of cDNA. PCR reaction contained 0.6 units of AmpliTaq Gold (Applied Biosystems), 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM of each dNTP and 0.5 µM of each primer. PCR were carried out under the following conditions: 94 °C for 10 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 1 min, 62 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. Purification was performed using the ExoSAP-IT® method and sequenced with a Big Dye Terminator v.3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit in an ABI 3730 analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Polymorphisms were identified using SeqScape v2.5 program (Applied Biosystems).

miRDB74 program was run to find putative target miRNAs in the 3′UTR region of FABP4. For this purpose, the human miRNA database was used.

Detection of polymorphisms in the promoter region of the FADS2 gene

Polymorphisms in the proximal promoter region of the FADS2 gene were identified from the whole-genome sequence data of seven founders of the IBMAP experimental population (SRA accession numbers: SRR5229970, SRR5229971, SRR5229972, SRR5229973, SRR5229974, SRR5229975, and SRR5229976) using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) software46.

Gene expression profiling

Total RNA was isolated from the BF of the 115 BC1_LD samples with RiboPure™ RNA Purification Kit (Ambion; Austin, TX, USA). Total RNA was quantified in a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop products; Wilmington, DE, USA). The RNA was converted to cDNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) in 20 µl of reactions, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA samples were loaded into a Dynamic Array 48.48 chip in a BioMark system (Fluidigm; San Francisco, CA, USA) through an integrated fluidic circuit controller following a protocol previously described19.

For this experiment, the expressed levels of 48 genes were analyzed: 44 target genes and four reference genes (ACTB, B2M, HPRT1, and TBP). The ACTB and TBP were the two most stable reference genes and were used to normalize the expression levels of the target genes. Primers used for the analysis were designed using PrimerExpress 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems) and are detailed in Supplementary Table S12. Data was collected using the Fluidigm Real-Time PCR analysis software 3.0.2 (Fluidigm) and analyzed using the DAG expression software 1.0.5.575 applying the relative standard curve method. Samples targeted in this study were analyzed in duplicate. The normalized quantity (NQ) values of each sample and assay were used to compare our data. Data obtained were normalized by performing log2 transformation of the NQ value. The sex effect was also tested by using a linear model with the lm function of R program76.

Gene expression association analysis

In order to detect SNPs associated with gene expression levels, eGWAS was performed using as phenotype the expression values of 43 genes in adipose tissue. A mixed model (1) was employed in Qxpak 5.077:

| 1 |

in which Yijk was the kth individual expression record of each one of the 43 analyzed genes, sex (two levels) and batch (corresponding to the slaughterhouse group; five levels) were fixed effects, λl was a −1 (aa), 0 (Aa), +1 (AA) indicator variable depending on the kth individual’s genotype for the lth SNP, al represents the additive effect associated with the lth SNP, uk is the infinitesimal genetic effect with random distribution N(0, Aσu2) where A is the numerator of the pedigree-based relationship matrix and the eijkl the residual.

The association analyses of the ACSM5 (rs331702081), ELOVL6 (ELOVL6:c.-533C>T, ELOVL6:c.-480C>T, ELOVL6:c.-394G>A, ELOVL6:c.416 C>T, ELOVL6:c.1408 A>G, and ELOVL6:c.1922C>T), FABP4 (FABP4:g.2634_2635insC and FABP4:g.6723 A>G), and FADS2 (rs331050552) polymorphisms with the ACSM5, ELOVL6, FABP4, and FADS2 mRNA expression, respectively, were performed using the same mixed model described above.

The R package q-value was used to calculate the false discovery rate (FDR), and the cut-off of the significant association at the whole genome level was set at the q-value ≤ 0.0577,78, meaning that 5% of all significant p-values will be false positives.

The identified SNPs were classified as cis when they were at 5 Mb upstream or downstream of the gene position and as trans when they were located elsewhere in the genome. Significant associated SNPs located less than 10 Mb apart were considered as belonging to the same interval.

Gene annotation and functional classification

The significantly associated SNPs (FDR ≤ 0.05) identified were mapped in the Sscrofa10.2 assembly and were annotated with the Ensembl Genes 84 Database using VEP software79.

The genomic eQTL intervals were annotated using Biomart software [http://www.biomart.org] adding a genomic region of one Mb from the start and end of each trans-eQTLs. Only the studied candidate gene was annotated for cis-eQTLs.

The Core Analysis function included in IPA was used to perform the functional analysis of genes mapped in the 19 eQTL regions. This software was used for data interpretation in the context of biological processes, pathways and networks. All information generated is derived from the Ingenuity Pathway Knowledge Base (IPKB), which is based on functions and interactions of genes published in the literature. RNA-Seq data of BF from BC1_LD individuals17 and Gene Expression Atlas80 were used to determine which of the lipid-related genes annotated in the genomic eQTL intervals were expressed in adipose tissue. Finally, a prediction analysis of TF binding sites was performed in the promoter region of the annotated genes. The iRegulon Cytoscape plugin65 was used to analyze the TFs and their related target genes. iRegulon relies on the analysis of the regulatory sequences around each gene, and use databases of nearly 10,000 TF motifs and 1,000 ChIP-seq data sets or “tracks”. In the present study, a high NES threshold value (NES > 5) was considered for the selection of potential relationships (the default NES cut-off in iRegulon is 3). A high NES score indicates (1) a motif that recovers a large proportion of the input genes within the top of its ranking and (2) higher reliability.

Gene expression and correlation analysis with phenotypes

A correlation analysis was performed to explore the association among the expressions of the 43 genes. Moreover, to analyze the relationships between gene expression and phenotypes, Pearson’s correlations among gene expression and FA composition percentages in BF6 and Longissimus dorsi muscle5 were performed. If required, data was normalized applying the log2 transformation. Then, gene expression and the composition of FA in BF and muscle were corrected both by gender (two levels) and batch effects (five levels), and the composition of FA traits was also adjusted for carcass weight, using the glm R package81. The remaining residuals of the phenotypes and gene expression values corrected for the corresponding effects were used to obtain the pairwise correlations. The hierarchical clustering option of PermutMatrix software82 was used to visualize the results of both traits and genes.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by the MINECO AGL2014-56369-C2-R and AGL2017-82641-R grants. MR was funded by a Formació i Contractació de Personal Investigador Novell (FI-DGR) PhD grant from Generalitat de Catalunya (ECO/1639/2013). MB was financially supported by a Ramon y Cajal contract (RYC-2013-12573) from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, APO was funded by a Personal Investigador en Formación (PIF) PhD grant from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (458-01-1/2011), DCP by a Formació i Contractació de Personal Investigador Novell (FI-DGR) PhD grant from Generalitat de Catalunya (ECO/1788/2014) and LCM was funded by a FPI PhD grant from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (BES-2015-075403).

We thank to all the members of the INIA, IRTA, and UAB institutions who contributed to the generation of the animal material used in this work, funded by grant INIA CPE03-010-C3. We acknowledge financial support from the “Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D” 2016-2019 (SEV‐2015‐0533) and the CERCA Programme / Generalitat de Catalunya.

Author Contributions

J.M.F. and M.B. conceived and designed the experiments; J.M.F. was the principal investigator of the project; A.I.F. and J.M.F. collected samples; M.R., A.P.O., and A.C. performed the DNA and RNA isolation; M.R., M.B., and J.M.F. performed the expression analysis; The polymorphisms genotyping was done by M.R., D.C.P., and L.C.M.; M.R., M.B., and A.P.O. analyzed the data; M.R., M.B., and J.M.F. wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Maria Ballester and Josep M. Folch contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20473-3.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.OECD/FAO. “OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook”, OECD Agriculture statistics (database). 10.1787/60b7ee42-en (2016).

- 2.Wood JD, et al. Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2008;78:343–358. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wood JD, et al. Effects of breed, diet and muscle on fat deposition and eating quality in pigs. Meat Sci. 2004;67:651–667. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casellas J, et al. Bayes factor analyses of heritability for serum and muscle lipid traits in Duroc pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2010;88:2246–54. doi: 10.2527/jas.2009-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramayo-Caldas Y, et al. Genome-wide association study for intramuscular fatty acid composition in an Iberian × Landrace cross. J. Anim. Sci. 2012;90:2883–93. doi: 10.2527/jas.2011-4900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muñoz M, et al. Genome-wide analysis of porcine backfat and intramuscular fat fatty acid composition using high-density genotyping and expression data. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:845. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang B, et al. Genome-wide association analyses for fatty acid composition in porcine muscle and abdominal fat tissues. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65554. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, et al. Genetic architecture of fatty acid composition in the longissimus dorsi muscle revealed by genome-wide association studies on diverse pig populations. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2016;48:5. doi: 10.1186/s12711-016-0184-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, et al. Genome-wide association studies for fatty acid metabolic traits in five divergent pig populations. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24718. doi: 10.1038/srep24718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robinson MR, Wray NR, Visscher PM. Explaining additional genetic variation in complex traits. Trends Genet. 2014;30:124–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schadt EE, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilad Y, Rifkin SA, Pritchard JK. Revealing the architecture of gene regulation: the promise of eQTL studies. Trends Genet. 2008;24:408–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frayn KN, Arner P, Yki-Järvinen H. Fatty acid metabolism in adipose tissue, muscle and liver in health and disease. Essays Biochem. 2006;42:89–103. doi: 10.1042/bse0420089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernlohr, D. A., Jenkins, A. E. & Bennaars, A. A. Chapter 10 Adipose tissue and lipid metabolism. In New Comprehensive Biochemistry, Vol. 36, pp. 263–289 (New Comprehensive Biochemistry, 2002).

- 15.Puig-Oliveras A, et al. Expression-based GWAS identifies variants, gene interactions and key regulators affecting intramuscular fatty acid content and composition in porcine meat. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31803. doi: 10.1038/srep31803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ballester M, et al. Integration of liver gene co-expression networks and eGWAs analyses highlighted candidate regulators implicated in lipid metabolism in pigs. Sci Rep. 2017;7:46539. doi: 10.1038/srep46539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corominas J, et al. Analysis of porcine adipose tissue transcriptome reveals differences in de novo fatty acid synthesis in pigs with divergent muscle fatty acid composition. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:843. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corominas J, et al. Polymorphism in the ELOVL6 gene is associated with a major QTL effect on fatty acid composition in pigs. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramayo-Caldas Y, et al. From SNP co-association to RNA co-expression: novel insights into gene networks for intramuscular fatty acid composition in porcine. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puig-Oliveras A, et al. A co-association network analysis of the genetic determination of pig conformation, growth and fatness. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e114862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballester M, et al. Analysis of the porcine APOA2 gene expression in liver, polymorphism identification and association with fatty acid composition traits. Anim. Genet. 2016;47:552–9. doi: 10.1111/age.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehzad A, Iqbal W, Shehzad O, Lee YS. Adiponectin: regulation of its production and its role in human diseases. Hormones (Athens) 2012;11:8–20. doi: 10.1007/BF03401534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dai MH, et al. Cloning, expression and chromosome localization of porcine adiponectin and adiponectin receptors genes. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2006;30:117–25. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung VG, Spielman RS. Genetics of human gene expression: mapping DNA variants that influence gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:595–604. doi: 10.1038/nrg2630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee C, Huang CH. LASAGNA-Search: an integrated web tool for transcription factor binding site search and visualization. BioTechniques. 2013;54:141–53. doi: 10.2144/000113999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XL, et al. Ablation of ARNT/HIF1beta in liver alters gluconeogenesis, lipogenic gene expression, and serum ketones. Cell Metab. 2009;9:428–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rankin EB, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2009;29:4527–38. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00200-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szanto A, et al. STAT6 transcription factor is a facilitator of the nuclear receptor PPARγ-regulated gene expression in macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunity. 2010;33:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corominas J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of the ELOVL6 gene is associated with a major QTL effect on fatty acid composition in pigs. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2015;47:20. doi: 10.1186/s12711-015-0111-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorenzo DN, et al. Ankyrin-B metabolic syndrome combines age-dependent adiposity with pancreatic β cell insufficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:3087–102. doi: 10.1172/JCI81317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guillou H, Zadravec D, Martin PG, Jacobsson A. The key roles of elongases and desaturases in mammalian fatty acid metabolism: Insights from transgenic mice. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:186–99. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Estany J, Ros-Freixedes R, Tor M, Pena RN. A functional variant in the stearoyl-CoA desaturase gene promoter enhances fatty acid desaturation in pork. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e86177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerbens F, et al. The adipocyte fatty acid-binding protein locus: characterization and association with intramuscular fat content in pigs. Mamm. Genome. 1998;9:1022–6. doi: 10.1007/s003359900918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Estellé J, et al. Characterization of the porcine FABP5 gene and its association with the FAT1 QTL in an Iberian by Landrace cross. Anim. Genet. 2006;37:589–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2052.2006.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ballester M, et al. Association of genetic variants and expression levels of porcine FABP4 and FABP5 genes. Anim. Genet. 2017 doi: 10.1111/age.12620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ojeda A, Rozas J, Folch JM, Pérez-Enciso M. Unexpected high polymorphism at the FABP4 gene unveils a complex history for pig populations. Genetics. 2006;174:2119–27. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.063057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi RL, Chen Y, Huang JX, Yang FY. Effects of conjugated linoleic acid on the expression levels of miR-27 and miR-143 in pig adipose tissue. Genet. Mol. Res. 2015;14:6985–92. doi: 10.4238/2015.June.26.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boutet E, et al. Seipin deficiency alters fatty acid Delta9 desaturation and lipid droplet formation in Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy. Biochimie. 2009;91:796–803. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu L, et al. Adipose-specific knockout of SEIPIN/BSCL2 results in progressive lipodystrophy. Diabetes. 2014;63:2320–31. doi: 10.2337/db13-0729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang RY, et al. Ablation of a galectin preferentially expressed in adipocytes increases lipolysis, reduces adiposity, and improves insulin sensitivity in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:18696–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109065108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satish L, et al. Expression analysis of human adipose-derived stem cells during in vitro differentiation to an adipocyte lineage. BMC Med Genomics. 2015;8:41. doi: 10.1186/s12920-015-0119-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pang XY, et al. Structure/function relationships of adipose phospholipase A2 containing a cys-his-his catalytic triad. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:35260–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.398859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu X, et al. CYP1B1 deficiency ameliorates obesity and glucose intolerance induced by high fat diet in adult C57BL/6J mice. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:761–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taniguchi M, et al. Genomic structural analysis of porcine fatty acid desaturase cluster on chromosome 2. Anim. Sci. J. 2015;86:369–77. doi: 10.1111/asj.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Childs CE, Hoile SP, Burdge GC, Calder PC. Changes in rat n-3 and n-6 fatty acid composition during pregnancy are associated with progesterone concentrations and hepatic FADS2 expression. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2012;86:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2012.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abdulla A, et al. Regulation of lipogenic gene expression by lysine-specific histone demethylase-1 (LSD1) J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:29937–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.573659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura MT, Nara TY. Structure, function, and dietary regulation ofdelta6, delta5, and delta9 desaturases. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2004;24:345–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.121803.063211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruan W, Lai M. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein: a possible marker for the metabolic syndrome? Acta Diabetol. 2010;47:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeong JK, Szabo G, Raso GM, Meli R, Diano S. Deletion of prolyl carboxypeptidase attenuates the metabolic effects of diet-induced obesity. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;302:E1502–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00544.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grove KL, Fried SK, Greenberg AS, Xiao XQ, Clegg DJ. A microarray analysis of sexual dimorphism of adipose tissues in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34:989–1000. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang X, et al. Tissue-specific expression and regulation of sexually dimorphic genes in mice. Genome Res. 2006;16:995–1004. doi: 10.1101/gr.5217506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Nas A, et al. Elucidating the role of gonadal hormones in sexually dimorphic gene coexpression networks. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1235–49. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bonen A, et al. Regulation of fatty acid transport by fatty acid translocase/CD36. Proc Nutr Soc. 2004;63:245–9. doi: 10.1079/PNS2004331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cao H, et al. Identification of a lipokine, a lipid hormone linking adipose tissue to systemic metabolism. Cell. 2008;134:933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sampath H, Miyazaki M, Dobrzyn A, Ntambi JM. Stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 mediates the pro-lipogenic effects of dietary saturated fat. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:2483–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fernández AI, et al. Validating porcine SCD haplotype effects on fatty acid desaturation and fat deposition in different genetic backgrounds. Livest. Sci. 2017;205:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2017.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ramsay RR, Gandour RD. Selective modulation of carnitine long-chain acyltransferase activities. Kinetics, inhibitors, and active sites of COT and CPT-II. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1999;466:103–9. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46818-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griffin MJ, Sul HS. Insulin regulation of fatty acid synthase gene transcription: roles of USF and SREBP-1c. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:595–600. doi: 10.1080/15216540400022474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carman GM, Han GS. Roles of phosphatidate phosphatase enzymes in lipid metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:694–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tomsig JL, et al. Lipid phosphate phosphohydrolase type 1 (LPP1) degrades extracellular lysophosphatidic acid in vivo. Biochem. J. 2009;419:611–8. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Damon M, Wyszynska-Koko J, Vincent A, Hérault F, Lebret B. Comparison of muscle transcriptome between pigs with divergent meat quality phenotypes identifies genes related to muscle metabolism and structure. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hajduch E, Litherland GJ, Hundal HS. Protein kinase B (PKB/Akt)–a key regulator of glucose transport? FEBS Lett. 2001;492:199–203. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02242-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Puig-Oliveras A, et al. Differences in muscle transcriptome among pigs phenotypically extreme for fatty acid composition. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janky R, et al. iRegulon: from a gene list to a gene regulatory network using large motif and track collections. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014;10:e1003731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peeters, A. & Baes, M. Role of PPARα in Hepatic Carbohydrate Metabolism. PPAR Res pii:572405, 10.1155/2010/572405 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Pérez-Enciso M, et al. A QTL on pig chromosome 4 affects fatty acid metabolism: evidence from an Iberian by Landrace intercross. J. Anim. Sci. 2000;78:2525–31. doi: 10.2527/2000.78102525x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Serra X, et al. A comparison of carcass, meat quality and histochemical characteristics of Iberian (Guadyerbas line) and Landrace pigs. Livest. Prod. Sci. 1998;56:215–223. doi: 10.1016/S0301-6226(98)00151-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. E. & Maniatis, T. In Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual 2nd edn., Vol 3, E3–E4 (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1989).

- 70.Ramos AM, et al. Design of a high density SNP genotyping assay in the pig using SNPs identified and characterized by next generation sequencing technology. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mercadé A, et al. Adipocyte fatty-acid binding protein is closely associated to the porcine FAT1 locus on chromosome 4. J. Anim. Sci. 2006;84:2907–13. doi: 10.2527/jas.2005-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;132:365–86. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wong N, Wang X. miRDB: an online resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D146–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ballester M, Cordón R, Folch JM. DAG expression: high-throughput gene expression analysis of real-time PCR data using standard curves for relative quantification. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80385. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. J Comput Graph Stat. 1996;5:299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pérez-Enciso M, Misztal I. Qxpak.5: old mixed model solutions for new genomics problems. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:202. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McLaren W, et al. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2069–70. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kapushesky M, et al. Gene expression atlas at the European bioinformatics institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D690–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hastie, T. J. & Pregibon, D. Generalized linear models. In Chambers, J. M. & Hastie, T. J. (Eds), Chapter 6 of Statistical Models in S. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole (Pacific grove, 1992).

- 82.Caraux G, Pinloche S. PermutMatrix: a graphical environment to arrange gene expression pro les in optimal linear order. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1280–1281. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.