ABSTRACT

Many microorganisms in the environment participate in the fermentation process of Chinese liquor. However, it is unknown to what extent the environmental microbiota influences fermentation. In this study, high-throughput sequencing combined with multiphasic metabolite target analysis was applied to study the microbial succession and metabolism changes during Chinese liquor fermentation from two environments (old and new workshops). SourceTracker was applied to evaluate the contribution of environmental microbiota to fermentation. Results showed that Daqu contributed 9.10 to 27.39% of bacterial communities and 61.06 to 80.00% of fungal communities to fermentation, whereas environments (outdoor ground, indoor ground, tools, and other unknown environments) contributed 62.61 to 90.90% of bacterial communities and 20.00 to 38.94% of fungal communities to fermentation. In the old workshop, six bacterial genera (Lactobacillus [11.73% average relative abundance], Bacillus [20.78%], Pseudomonas [6.13%], Kroppenstedtia [10.99%], Weissella [16.64%], and Pantoea [3.40%]) and five fungal genera (Pichia [55.10%], Candida [1.47%], Aspergillus [10.66%], Saccharomycopsis [22.11%], and Wickerhamomyces [3.35%]) were abundant at the beginning of fermentation. However, in the new workshop, the change of environmental microbiota decreased the abundances of Bacillus (5.74%), Weissella (6.64%), Pichia (33.91%), Aspergillus (7.08%), and Wickerhamomyces (0.12%), and increased the abundances of Pseudomonas (17.04%), Kroppenstedtia (13.31%), Pantoea (11.41%), Acinetobacter (3.02%), Candida (16.47%), and Kazachstania (1.31%). Meanwhile, in the new workshop, the changes of microbial community resulted in the increase of acetic acid, lactic acid, malic acid, and ethyl acetate, and the decrease of ethyl lactate during fermentation. This study showed that the environmental microbiota was an important source of fermentation microbiota and could drive both microbial succession and metabolic profiles during liquor fermentation.

IMPORTANCE Traditional solid-state fermentation of foods and beverages is mainly carried out by complex microbial communities from raw materials, starters, and the processing environments. However, it is still unclear how the environmental microbiota influences the quality of fermented foods and beverages, especially for Chinese liquors. In this study, we utilized high-throughput sequencing, microbial source tracking, and multiphasic metabolite target analysis to analyze the origins of microbiota and the metabolic profiles during liquor fermentation. This study contributes to a deeper understanding of the role of environmental microbiota during fermentation.

KEYWORDS: environmental microbiota, microbial succession, metabolic profiles, microbial source tracking, high-throughput sequencing

INTRODUCTION

With a long history, solid-state fermentation (SSF) of foods and beverages has been applied to improve the quality, safety, and nutritional effects of agricultural products (1). Traditional fermentation of foods and beverages is driven by microbes originating from raw materials, starters, and the processing environments (2). Although most modern fermented foods and beverages are inoculated with defined starters, environmental microbiota still participate in the production of many traditional foods and beverages, such as cheeses (2), wine (3), sourdough (4), and sake (1). Environmental microbiota affect the foods and beverages we consume; they can help break down macromolecules into small peptides and monosaccharides, produce various flavor components, and finally contribute to the quality of foods and beverages (5). However, environmental microbiota can also spoil foods, influence food flavors, or even damage health (6).

Fermentation of Chinese liquor is a traditional SSF process (7, 8). The traditional fermentation process of Chinese liquor (light-flavor liquor in this study) is as follows: (i) a mixture of sorghum and water (1:1.1) is steamed for 30 to 40 min and then cooled, (ii) the mixture is then mixed evenly with rice hull (steamed before use) and Daqu (20%), (iii) the mixture is put into pottery cylinder jars or stainless steel tanks for fermentation, and (iv) after fermenting for about 27 days, the fermented grain is distilled to produce liquor. During liquor fermentation, the raw materials encounter many environments (such as ground and tools) during their journey from grain to liquor (9). Therefore, the processing environments may act as potential habitats for fermentation microbiota. Study of the environmental microbiota is critical to understanding of the complete microbial ecosystem of liquor fermentation. Several research groups have been working on microbial ecology and metabolomics during Chinese liquor fermentation. Some studies showed that bacterial communities in Daqu (starter) used for Chinese liquor are dominated by Firmicutes and Actinobacteria, and nearly all of the fungal communities are Pichia kudriavzevii (known synonymously as Issatchenkia orientalis), a member of the Saccharomycetaceae (10). Moreover, a study on the variability of bacterial and fungal communities indicated that Lactobacillus acetotolerans, P. kudriavzevii, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae are the most dominant microbes during liquor fermentation (8). However, it is unknown where these microbes originate from, and to what extent the environmental microbiota influences fermentation. Furthermore, β-damascenone, ethyl acetate, ethyl lactate, acetic acid, and lactic acid are recognized as the key odorants in light-flavor Chinese liquor, influencing both the flavor and mouthfeel properties (11). Nevertheless, the relationships between microbial communities and liquor metabolic profiles are unknown.

There is no doubt that these studies described above help to promote the evolution of liquor fermentation, but the sources of fermentation microbiota and the influences of environmental microbiota on liquor fermentation are not well understood. In this study, we compared the bacterial and fungal community structures during liquor fermentation in different environments via high-throughput sequencing and microbial source tracking analysis. Meanwhile, the metabolites during fermentation were detected by a headspace solid-phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (HS-SPME-GC-MS) and by liquid chromatography. Finally, the relationships between microbial communities and metabolites were further verified. This work aimed to track the sources of fermentation microbiota, and evaluate how the environmental microbiota affects the microbial succession and metabolic profiles during fermentation.

RESULTS

Metabolic profiles during fermentation from different environments.

To elucidate the effect of environmental microbiota on liquor fermentation, we processed two batches of fermentation in different workshops (workshops A and B) in a famous light-flavor liquor distillery in Hebei province, China. Workshop A is 23 years old, and workshop B is only 4 years old (as described in Materials and Methods). We collected 20 fermented grain samples during fermentation (10 fermented grain A samples and 10 fermented grain B samples). A total of 58 metabolites were identified from the 20 samples, including 4 alcohols, 10 acids, 27 esters, 11 aromatics, and 6 others (Fig. 1A). Principal-component analysis (PCA) showed that the metabolic profiles in fermented grains A and B were similar at the beginning of fermentation (day 0). However, after fermenting for 4 days, the samples were divided as expected into fermented grain A or B (Fig. 1B). Although fermentation time was the main factor in the first principal-component axis (PC1, which contributed 69% of the total variation), different environments played an important role in the second principal-component axis (PC2, which contributed 22% of the total variation). Moreover, both heat mapping and PCA showed that the concentrations of acetic acid, lactic acid, malic acid, and ethyl acetate were higher in fermented grain B than those in fermented grain A, but the trend of ethyl lactate was just the opposite (Fig. 1; see also Table S1 in the supplemental material). Additionally, the total content of acids in fermented grain B was higher than that in that in fermented grain A, whereas the contents of ethanol, volatile alcohols, aromatics, and esters showed opposite trends (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

FIG 1.

Metabolic profiles during fermentation. (A) Heat map of metabolites in fermented grains A and B during fermentation. A total of 58 metabolites (including 4 alcohols, 10 acids, 27 esters, 11 aromatics, and 6 others) were clustered separately. The Z score was used for data standardization. (B) Principal-component analysis based on the metabolic composition. The metabolites contributing most to the variability between samples are indicated on the graph. Fermentation time is shown as 0 to 27, e.g., “27” represents the sample fermented for 27 days.

Microbial succession during fermentation from different environments.

We applied a quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) assay to detect the dynamics of bacterial and fungal biomass during fermentation. The dynamics of bacteria and fungi showed different tendencies between fermented grains A and B during fermentation. In fermented grain A, the bacterial biomass increased from 107.96 to 108.93 gene copies/g sample. In fermented grain B, the bacterial biomass was significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that in fermented grain A at 0 to 4 days during fermentation. However, the bacterial biomass in fermented grain B decreased in the following days (109.42 to 108.73 gene copies/g sample). Meanwhile, there was no significant difference between the fungal biomasses in fermented grains A and B at 0 to 15 days of fermentation. Nevertheless, the fungal biomass in fermented grain B (107.22 gene copies/g sample) was significantly higher than that in fermented grain A (105.63 gene copies/g sample) at the end of fermentation (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

High-throughput sequencing was applied to characterize the microbial community structures in Daqu, fermented grains, and environments (tools, indoor ground, outdoor ground, and control samples). Control samples were the fermented grains processed without Daqu, and we considered the microbes in control samples as integrated environmental microbes. We obtained 1,170,458 high-quality reads from the V3-V4 hypervariable region of bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences, and 1,730,473 high-quality reads from the fungal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region from all 38 samples. For bacteria, there was an average of 30,801 reads per sample, with a range from 18,808 to 81,784 reads. For fungi, there was an average of 45,538 reads per sample, with a range from 19,268 to 86,192 reads.

During fermentation, the microbial alpha diversities were different between fermented grains A and B. In fermented grain A, the bacterial diversity (operational taxonomic unit [OTU] numbers and Shannon indexes) declined along with fermentation time, but in fermented grain B, the bacterial diversity tended to fluctuate. After fermenting for 15 days, the bacterial diversity of fermented grain B was higher than that of fermented grain A. Moreover, the changes in fungal diversity were not obvious in both fermented grains A and B. However, the fungal OTUs and Shannon indexes of fermented grain B were higher than those of fermented grain A during fermentation (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

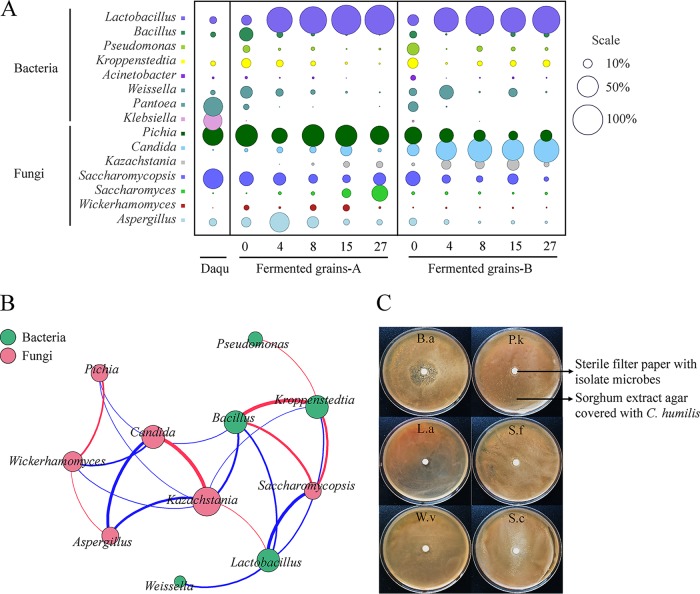

A total of 415 bacterial genera and 229 fungal genera were identified from all samples. Only eight bacterial genera and seven fungal genera were abundant (with over 1% average abundance) in Daqu or fermented grain samples (Fig. 2A). For bacterial communities, six genera (Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Kroppenstedtia, Weissella, Pantoea, and Klebsiella) were abundant in Daqu. During fermentation, Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Kroppenstedtia, Weissella, and Pantoea were also abundant in the beginning of fermentation (day 0), whereas the relative abundance of Klebsiella was less than 1%. Interestingly, Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter were only detected in fermented grain samples, and were more abundant in fermented grain B than in fermented grain A. After fermenting for 4 days, both fermented grain A and B samples were dominated by Lactobacillus (68.89 to 97.72% relative abundance; Fig. 2A). Lactobacillus brevis and Lactobacillus plantarum were more abundant in fermented grain A at 4 to 8 days of fermentation, whereas Lactobacillus paralimentarius was more abundant in fermented grain B (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). Moreover, both fermented grains A and B were dominated by Lactobacillus acetotolerans at the end of fermentation. Metastats software analysis revealed that 82 bacterial OTUs were significantly different (P < 0.001; q < 0.5) between fermented grains A and B, and six OTUs with over 0.1% average abundance were found. OTU1349 (Sphingobacterium) was only detected in fermented grain A, but five OTUs (OTU1487, OTU1786, OTU2610, OTU2624, and OTU4058) attached to Lactobacillus were more abundant in fermented grain B than in fermented grain A (see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

(A) Abundance of microbial communities in Daqu and fermented grains. The radius of each circle represents the average relative abundance (n = 2). (B) Relationships among microbial communities. A connection stands for a significant (P < 0.05) and strong (Spearman's ∣ρ∣ > 0.6) correlation. Size of each node is proportional to the number of connections, and the nodes are colored by kingdom (bacterium, green; fungus, red). The thickness of each connection (edge) between two nodes is proportional to the value of Spearman's correlation coefficient (ρ). The color of the edges corresponds to a positive (red) or negative (blue) relationship. (C) Effect of different microbes on Candida humilis in agar diffusion assay. B.a, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens; L.a, Lactobacillus acetotolerans; W.v, Weissella viridescens; P.k, Pichia kudriavzevii; S.f, Saccharomycopsis fibuligera; S.c, Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

For fungi, Pichia, Saccharomycopsis, and Aspergillus were abundant in both Daqu and fermented grain samples (Fig. 2A). However, Candida, Kazachstania, Saccharomyces, and Wickerhamomyces were only abundant in the fermented grain samples. Furthermore, Pichia, Wickerhamomyces, and Aspergillus were more abundant in fermented grain A during fermentation, whereas Candida and Kazachstania were more abundant in fermented grain B. Additionally, Saccharomycopsis and Saccharomyces were abundant in both fermented grains A and B at the beginning of fermentation, but after fermenting for 8 days, Saccharomyces was more abundant in fermented grain A than in fermented grain B. Metastats analysis revealed that 223 fungal OTUs were significantly different (P < 0.001; q < 0.5) between fermented grains A and B, and 24 OTUs in them were found with over 0.1% average abundance (see Table S3 in the supplemental material).

Microbial community structure in liquor-making environments.

The 15 abundant genera discussed above were also widely distributed across the environmental samples, and there were more similarities between fermented grains and environmental samples taken from the same habitat (workshop A or B; Table 1 and Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). For example, Bacillus, Weissella, and Wickerhamomyces were more abundant in both fermented grains and environments in workshop A than those in workshop B. Meanwhile, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and Candida were more abundant in both fermented grains and environments in workshop B (Fig. 2A, Table 1; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material).

TABLE 1.

Relative abundances of the bacterial and fungal communities in Daqu and environment

| Microbial genus | Relative abundance (%) ina: |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daqu | Workshop A |

Workshop B |

|||||||

| Control | Outdoor ground | Indoor ground | Tools | Control | Outdoor ground | Indoor ground | Tools | ||

| Bacteria | |||||||||

| Lactobacillus | 5.96 ± 0.44 | 7.66 ± 0.90 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 31.42 ± 8.15b | 34.62 ± 2.65b | 18.45 ± 23.96 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 2.59 ± 0.13 | 2.68 ± 0.19 |

| Bacillus | 3.35 ± 0.14 | 4.07 ± 3.10 | 0.11 ± 0.05 | 9.61 ± 0.49b | 8.99 ± 2.52b | 0.28 ± 0.14 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.72 ± 0.08 | 2.89 ± 0.30 |

| Pseudomonas | NDc | 1.12 ± 0.16 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | 40.65 ± 14.78b | 1.50 ± 0.00 | 0.29 ± 0.10 | 0.54 ± 0.58 |

| Kroppenstedtia | 3.12 ± 0.00b | 1.00 ± 0.08 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.18 ± 0.10 | 0.08 ± 0.04 | 0.14 ± 0.14 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 1.72 ± 0.22 |

| Acinetobacter | 0.46 ± 0.34 | 9.28 ± 4.14 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.22 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 24.50 ± 1.17b | 5.51 ± 0.14 | 4.33 ± 0.14 | 1.67 ± 1.44 |

| Weissella | 2.34 ± 0.50 | 1.22 ± 0.22 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 10.18 ± 0.12b | 7.39 ± 1.97b | 1.03 ± 0.87 | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 0.99 ± 0.08 | 4.02 ± 0.70 |

| Pantoea | 40.85 ± 6.47b | 0.55 ± 0.07 | 7.10 ± 0.65 | 2.02 ± 0.08 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 1.13 ± 0.21 | 0.13 ± 0.08 |

| Klebsiella | 39.03 ± 3.10b | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 3.45 ± 0.46 | 3.45 ± 0.87 | ND | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 1.16 ± 0.09 | 2.67 ± 2.96 |

| Other bacteria | 4.86 ± 1.94 | 74.85 ± 4.94 | 91.74 ± 0.68 | 42.37 ± 6.85 | 45.32 ± 2.8 | 14.83 ± 6.00 | 91.17 ± 0.26 | 88.31 ± 0.93 | 83.68 ± 4.69 |

| Fungi | |||||||||

| Pichia | 48.17 ± 14.14 | 23.49 ± 6.24 | 1.65 ± 0.26 | 34.37 ± 5.80 | 34.49 ± 1.00 | 42.98 ± 24.15 | 1.82 ± 0.41 | 14.2 ± 1.47 | 3.09 ± 0.75 |

| Candida | 0.20 ± 0.10 | 1.22 ± 0.25 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | 2.60 ± 0.44 | 0.74 ± 0.11 | 11.13 ± 3.23b | 2.99 ± 1.81 | 2.23 ± 1.34 | 12.36 ± 0.11b |

| Kazachstania | ND | 0.30 ± 0.18 | ND | 0.01 ± 0.01 | ND | 0.66 ± 0.29 | ND | ND | ND |

| Saccharomycopsis | 44.69 ± 12.29b | 2.21 ± 0.48 | 4.48 ± 1.85 | 11.52 ± 0.57 | 2.82 ± 0.76 | 3.26 ± 0.91 | 2.82 ± 1.78 | 5.28 ± 3.46 | 7.49 ± 1.49 |

| Saccharomyces | 0.19 ± 0.09 | 20.97 ± 17.90 | 0.28 ± 0.13 | 8.86 ± 0.71 | 2.95 ± 0.41 | 17.42 ± 10.58 | 0.22 ± 0.09 | 1.63 ± 0.70 | 0.36 ± 0.11 |

| Wickerhamomyces | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.36 ± 0.10 | 0.17 ± 0.10 | 1.91 ± 0.11b | 0.57 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.14 | 0.07 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.26 | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| Aspergillus | 6.44 ± 2.22 | 24.45 ± 17.50 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.13 | 0.41 ± 0.18 | 2.53 ± 1.16 | 0.47 ± 0.38 | 0.53 ± 0.07 | 0.91 ± 0.10 |

| Other fungi | 0.25 ± 0.17 | 26.99 ± 5.78 | 92.39 ± 1.31 | 39.89 ± 6.40 | 58.02 ± 1.38 | 21.86 ± 7.85 | 91.62 ± 4.51 | 75.58 ± 0.25 | 75.59 ± 2.37 |

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (n = 2).

The abundance is significantly different among Daqu and environments in workshops A and B. Significance is defined at P < 0.05 (with false discovery rate correction), as determined by a one-way ANOVA Duncan's test.

ND, not detected.

The genera shared among fermented grains, Daqu, and control samples (considered integrated environmental microbes) were analyzed via Venn analysis (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). At the beginning of fermentation (day 0), a total of 105 bacterial genera and 72 fungal genera were identified in fermented grains A and B. Venn analysis showed that 72 genera were shared between fermented grains A and B, including 45 bacterial genera (accounting on average for 91.25% of total bacteria) and 27 fungal genera (95.06% of total fungi on average) (Fig. S6A). Among these genera, 43 genera could be detected in Daqu, 63 genera in control A, and 59 genera in control B (Fig. S6B). Furthermore, 71 genera (54 bacteria [3.99% of bacteria in fermented grain A] and 17 fungi [0.56% of fungi in fermented grain A]) were exclusive to fermented grain A, and 34 genera (6 bacteria [0.05% of bacteria in fermented grain B] and 28 fungi [1.09% of fungi in fermented grain B]) were exclusive to fermented grain B. Daqu shared only four and nine genera with fermented grains A and B, respectively. However, the control samples shared 33 genera (23 bacteria and 10 fungi) and 31 genera (4 bacteria and 27 fungi) with fermented grains A and B, respectively (Fig. S6C and D).

To illuminate the interactions among microbes during fermentation, we explored the correlations of microbes in fermented grains based on Spearman's rank correlations (∣ρ∣ > 0.6 and P < 0.05). In total, 8 pairs of positive correlations and 14 pairs of negative correlations (edges) were identified from 11 genera (nodes) (Fig. 2B). The network that we generated showed that the 11 genera (except for Weissella) were divided into three groups. The first group included Pseudomonas, Kroppenstedtia, Bacillus, and Saccharomycopsis. The second group included Candida, Kazachstania, and Lactobacillus. The third group included Pichia, Wickerhamomyces, and Aspergillus. Furthermore, presence of the second group was negatively correlated with that of both the first and third groups. Since Candida is an abnormal microbe during the liquor fermentation process (8), we further verified the relationships between Candida and the other microbes. The main OTU (OTU2964) of Candida was closest to Candida humilis (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material). We isolated C. humilis and six other microbes (Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, Lactobacillus acetotolerans, Weissella viridescens, Pichia kudriavzevii, Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) from fermented grains samples. Agar diffusion experiment showed that B. amyloliquefaciens could strongly inhibit the growth of C. humilis (Fig. 2C).

Relationships between microbial communities and metabolites.

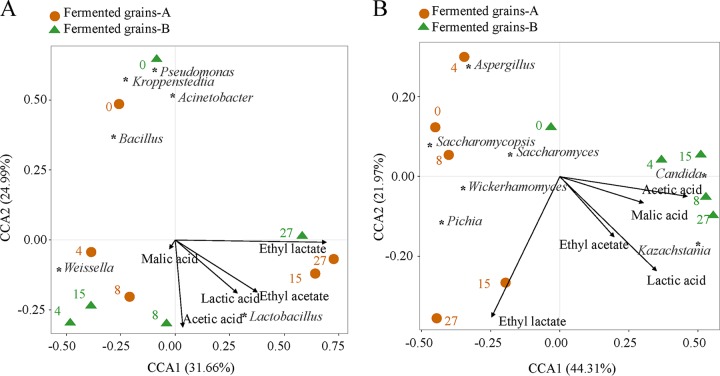

To detect the relationships between microbial communities and metabolites, canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) was conducted based on the bacterial and fungal communities and the metabolites (Fig. 3). Overall, the two axes explained 56.65% and 66.28% of the total variance in bacterial and fungal community differentiation, respectively, suggesting remarkable correlations between microbial communities and metabolites. The bacterial communities in both fermented grains A and B showed similar tendencies (Fig. 3A). However, the successions of fungal communities were different between fermented grains A and B (Fig. 3B). Different environments led to higher abundances of Candida and Kazachstania in fermented grain B. Moreover, CCA revealed that abundant Candida and Kazachstania were positively correlated with the production of acetic acid, lactic acid, and malic acid in fermented grain B.

FIG 3.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) of microbial community composition and metabolites during fermentation. (A) CCA based on bacterial community showed similar trends between the bacterial communities in fermented grains A and B. (B) CCA based on fungal community showed distinct differences between the fungal communities in fermented grains A and B. Responding microbial communities are indicated on the graph. Correlations with metabolites are indicated by the arrows.

SourceTracker analysis highlights the contribution of environmental sources to fermentation.

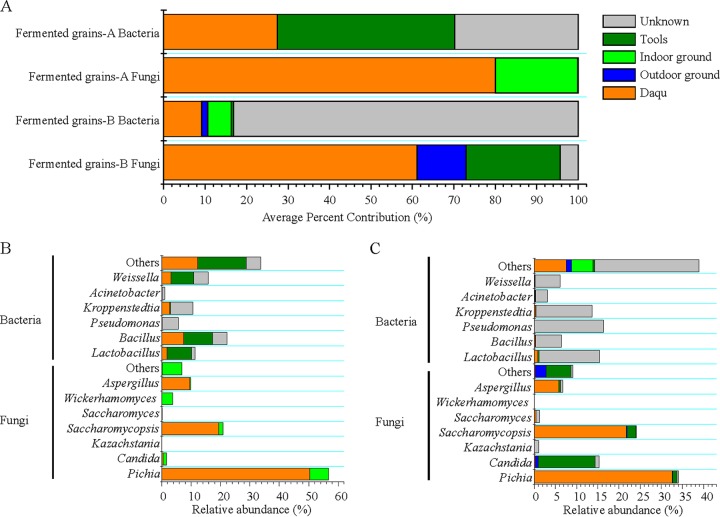

We used SourceTracker, a Bayesian probability tool (12), to predict the sources of microbes found in fermented grains. For bacterial communities, results revealed that Daqu only contributed 27.39% of bacterial communities to fermented grain A, and 9.10% to fermented grain B (Fig. 4A). The environments (outdoor ground, indoor ground, tools, and other unknown environments) contributed most of the bacterial communities in both fermented grains A (62.61%) and B (90.90%). For fermented grain A, tools were the main environmental source of bacterial communities, contributing Lactobacillus [8.47% relative abundance], Bacillus [9.82%], Weissella [7.63%], and other bacteria [16.49%] (Fig. 4B). However, for fermented grain B, the main environmental source of bacterial communities was unknown (Fig. 4C).

FIG 4.

SourceTracker results highlight the percentages of inferred sources of bacterial and fungal communities in fermented grains. (A) Average percent contribution of source communities. (B) Source-tracking analysis of bacterial and fungal communities in fermented grain A. (C) Source-tracking analysis of bacterial and fungal communities in fermented grain B.

For fungal communities, Daqu was the main source of both fermented grains A (80.00%) and B (61.06%), whereas environments contributed 19.93% of fungal communities to fermented grain A, and 34.61% to fermented grain B. For fermented grain A, indoor ground was the main environmental source of fungal communities, contributing 6.39% of Pichia and 3.72% of Wickerhamomyces (Fig. 4B). For fermented grain B, tools were the main environmental source of fungal communities, contributing 13.41% of Candida, followed by outdoor ground (contributing 0.74% of Candida) (Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

Chinese liquor fermentation, as a traditional SSF process, employs diverse microbes from Daqu and the environment (9). In this study, we provided a systematic view of the influences of environmental microbiota on microbial succession and metabolism during liquor fermentation. We confirm that the environmental microbiota contains abundant fermentation-associated microbes, and environmental microbiota is a principal factor in fermentation microbiota and metabolism.

The microbial communities in fermented grains were composed of Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, yeasts, and filamentous fungi that have been widely detected in Daqu (13–16). Interestingly, we found that these microbes were also widely distributed in the liquor-making environments (tools, indoor ground, and outdoor ground). Several microbes (including Lactobacillus, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, Weissella, Candida, Kazachstania, Saccharomyces, and Wickerhamomyces) were more abundant in these environments than in Daqu (Table 1 and Fig. S4). SourceTracker was applied to identify the sources of microbes found in fermented grains, and showed that both Daqu and the environments had important influences on fermentation (Fig. 4). Previous studies also indicated that environmental microbiota participates in the fermentation processes of many fermented foods and beverages (1, 2), which might provide additional evidence that the environmental microbiota is an important source of fermentation microbiota.

Moreover, both microbial community structure and Venn analysis showed several microbes that distinguished the fermented grains and environments from different habitats (workshops A and B). We found liquor-fermentation-associated Firmicutes (e.g., Bacillus and Weissella, mainly from the tools), and yeasts (e.g., Wickerhamomyces, mainly from the indoor ground) were more abundant in both fermented grains and environments in workshop A, but Proteobacteria (e.g., Pseudomonas and Acinetobacter from other unknown environments) and Candida (from the tools) were more abundant in workshop B (Fig. 2A, 4, and S4). Bacillus (mainly OTU1490, closest to B. amyloliquefaciens; Fig. S4 and S5), Weissella (mainly OTU3084, closest to Weissella viridescens), and Wickerhamomyces (mainly OTU6292, closest to Wickerhamomyces anomalus) have been reported as functional microbes during liquor fermentation in previous studies (15, 17). However, Pseudomonas (mainly OTU4305, closest to Pseudomonas poae) and Acinetobacter (mainly OTU4167, closest to Acinetobacter pittii) have been reported as spoilage-associated bacteria that have negative impacts on fermentation (18). Additionally, Candida is an abnormal microbe during the liquor fermentation process, and the function of Candida (mainly OTU2964, closest to C. humilis) during the Chinese liquor fermentation process is still unknown (8). Interestingly, both network analysis and the agar diffusion experiment showed that Bacillus could strongly inhibit the growth of Candida (Fig. 2B and C). This finding could be explained by Bacillus secreting iturin A (19) or bacillomycin D (20) to inhibit the growth of Candida. Both Candida and Bacillus in fermented grains mainly originated from the environments (Fig. 4B and C). Compared with environments in workshop A, environments in workshop B had less Bacillus content (Table 1). Moreover, although Daqu contributed plentiful Bacillus during fermentation, Bacillus content declined quickly during fermentation (Fig. 2A and 4). It was suggested that living cells of Bacillus are required for the robustness of microbial ecology for both the environments and liquor fermentation. Furthermore, although Pichia (mainly OTU6258, closest to Pichia kudriavzevii) was mainly from Daqu, Pichia was more abundant in both fermented grains and environments in workshop A than in workshop B. In this study, workshop A has made liquor for 23 years, and workshop B has made liquor for only 4 years. We supposed that fermentation-associated microbes would also establish themselves in the environment during fermentation, but the establishment of fermentation microbiota was slow. Thus, although the same Daqu microbiome was inoculated in both fermentation processes, environmental microbiota differentiated these two liquor fermentation processes from workshops A and B.

Furthermore, we found that environmental microbiota influenced both the microbial succession and the metabolic profiles during fermentation. For bacterial communities, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, Kroppenstedtia, Acinetobacter, Weissella, and Pantoea declined immediately during fermentation, giving way to Lactobacillus in both fermented grains A and B. Lactobacillus was dominant in all light-flavor liquors (8), strong-flavor liquors (5, 21), maotai-flavor liquors (22), and in other beverage fermentation processes (e.g., that of sake) (1). For fungal communities, Pichia, Wickerhamomyces, and Aspergillus were more abundant in fermented grain A when fermented for 0 to 8 days (Fig. 2A and S2). Pichia (mainly OTU6258, closest to P. kudriavzevii) and Wickerhamomyces (mainly OTU6292, closest to W. anomalus) were dominant functional fungi in light-flavor liquor, and can produce various esters and aromatics during fermentation (8, 17). Aspergillus (mainly OTU2194, closest to Aspergillus oryzae/flavus) is an important filamentous fungus that can produce many enzymes to degrade starch materials into fermentable sugars during liquor fermentation (23). Thus, the lower abundances of Pichia, Wickerhamomyces, and Aspergillus in fermented grain B might lead to the decrease of flavor compounds (volatile alcohols, aromatics, and esters; see Fig. S1). However, Candida and Kazachstania were more abundant in fermented grain B (Fig. 2A and S2). Candida (mainly OTU2964, closest to C. humilis, which has been reassigned to Kazachstania humilis [24]) is the main yeast in type I sourdoughs, and it determines the concentration of acetic acid in type I sourdoughs (25, 26). Previous study also indicated that the genus Candida is an abnormal microbe in the light-flavor liquor fermentation process (8). C. humilis and strictly heterofermentative lactic acid bacteria (LAB) species can shift ethanol formation to acetate production in type I sourdoughs (26). Moreover, CCA also showed that Candida and Kazachstania were positively correlated with acetic acid (Fig. 3B). This appears to be evidence that environmental microbiota can drive microbial succession during fermentation, subtly shaping liquor qualities.

In conclusion, this study highlights that environmental microbiota is an important source of fermentation microbiota. Environmental microbiota can drive the stability of the liquor fermentation ecosystem, and is highly relevant to the microbial succession and metabolic profiles during liquor fermentation. Given the importance of environmental microbiota, high-density distillery environment monitoring will be done to monitor the critical control points during liquor fermentation in further studies. Environmental ecosystem surveillance may become a new field for the study of microbial ecology in liquor and other food fermentation systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental design and sample collection.

The experimental site is located at a famous light-flavor liquor distillery in Hebei province, China (37° 71′N; 115° 69′E). We processed two batches of fermentation in different workshops (workshops A and B). Workshop A is 23 years old and uses traditional pottery cylinder jars for liquor fermentation. Workshop B is only 4 years old and uses stainless steel tanks for liquor fermentation. According to the fermentation process described in previous study (8), two batches of fermentation were processed with Daqu (starter) in workshops A and B. Based on previous study, the 15th day is important for the fermentation process (5). Hence, samples were collected on days 0, 4, 8, 15, and 27 (the end of fermentation). The Daqu for initiating the fermentation was also sampled. The environmental samples were taken from the tools, indoor ground, and outdoor ground. Environmental sampling was carried out using sterile degreasing cotton premoistened with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (0.1 M). Degreasing cotton was rubbed across the tools and the ground surface (1.00 m2). As control subjects, two other batches of fermentation were processed without Daqu under the same operating conditions in workshops A and B. Two parallel samples were collected for each sample type. Finally, all 38 samples (fermented grain A samples [n = 10], control A samples [n = 2], tool A samples [n = 2], indoor ground A samples [n = 2], outdoor ground A samples [n = 2]; fermented grain B samples [n = 10], control B samples [n = 2], tool B samples [n = 2], indoor ground B samples [n = 2], outdoor ground B samples [n = 2], and Daqu samples [n = 2]) were transferred into the lab on ice and analyzed within 3 h.

Ethanol and organic acid analysis.

To analyze the ethanol and organic acid content in fermented grain samples, 5-g samples were added to 20 ml distilled water, ultrasonically treated at 0°C for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 4°C and 8,000 × g for 5 min. The obtained supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm syringe filter (Nylon Acrodisc, Waters Co., Milford, MA) prior to determining the ethanol and organic acid content.

The ethanol content was detected via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Agilent 1200 HPLC, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) with a column (Aminex HPX-87H, 300 mm × 7.8 mm, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a refractive index detector (RID) (WGE, Germany), based on the method described by Wu et al. (27).

The organic acid content was determined on a Waters Acquity ultraperformance liquid chromatography (UPLC) H-Class system (Waters, Milford, MA) equipped with a quaternary solvent manager, an auto-sampler, a column compartment, a photodiode array, and an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 analytical column (100 mm × 2.1 mm inside diameter [i.d.], 1.8 μm film thickness; Waters, Milford, MA) based on the method described by Tang et al. (28).

Volatile organic compound analysis.

Fermented grains sample (5 g) were added to 20 ml sterile saline (0.85% NaCl, 1% CaCl2), ultrasonically treated at 0°C for 30 min, and then centrifuged at 4°C and 8,000 × g for 5 min. Eight milliliters of supernatant and 20 μl menthol (internal standard, 100 μg/ml) were placed into a 20-ml headspace vial with 3 g NaCl. Volatile organic compounds were determined by HS-SPME-GC-MS (GC 6890N and MS 5975; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) on a DB-Wax column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness; J&W Scientific, Folsom, CA), based on the method described by Gao et al. (11).

Total DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing.

Total DNA was isolated via the E.Z.N.A. (easy nucleic acid isolation) soil DNA kit (Omega bio-tek, Norcross, GA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For bacteria, the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using the universal primer sets F338 and barcode-R806 (29). For fungi, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was amplified with primers ITS1F and ITS2R (30). PCR products were purified by a PCR purification kit, and the concentrations were carefully assessed by the Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 8000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The barcoded PCR products were sequenced on a MiSeq benchtop sequencer for 250-bp paired-end sequencing (2 × 250 bp; Illumina, San Diego, CA) at Beijing Auwigene Tech. Ltd. (Beijing, China).

All of the generated raw sequences were processed via Qiime (v1.8.0) (31). Briefly, the raw sequences were quality trimmed and the sequences with quality scores <30 were trimmed. Only sequences over 200 bp in length were chosen for further analysis. The sequences that did not perfectly match the PCR primer, had nonassigned tags, or had an N base were removed (31). Chimera sequences were removed using the Uchime algorithm (32). After that, a distance matrix was calculated from the aligned sequences and OTUs were clustered using a 97% identity threshold by Qiime's uclust pipeline (33). A single representative sequence from each clustered OTU was used to align to the Greengenes database (v13.8) (34) and the UNITE fungal ITS database (v6.0) (35). Before further analysis, singleton OTUs were removed. Shannon biodiversity indexes were calculated by Qiime (v1.8.0).

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to estimate microbial biomass.

To estimate the biomass of bacteria and fungi during fermentation, absolute quantification qPCR assays were carried out using an Applied Biosystems StepOne real-time PCR platform (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with a commercial kit (QuantiFast SYBR green PCR kit; Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The total genomic DNA was measured (Nanodrop 8000; Wilmington, DE) and used as the template to amplify bacteria with Eub338/Eub518, and fungi with 5.8s/ITS1f (36). The amplification conditions were as follows: preheating at 95°C for 5 min, and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s, and increases of 0.5°C every 5 s from 65°C to 95°C for melting curve analysis. For the construction of a calibration curve, the plasmid DNA for quantifying the bacteria was constructed based on the 16S rRNA gene from species of L. acetotolerans. The plasmid DNA for quantifying the fungi was constructed based on the ITS gene from the species P. kudriavzevii. Tenfold serial dilutions of the above plasmids were amplified according to the PCR system and conditions described above. For each assay, a calibration curve for the calculation of bacteria or fungi was generated by plotting the threshold cycle (CT) values against the log10 16S rRNA gene or ITS gene copy numbers, respectively. The calibration curve and gene copies per gram sample were calculated as described previously (37). The amplification efficiency and calibration curve R2 value for bacteria were 106% and 0.9997 (Fig. S2A), respectively, and those for fungi were 110% and 0.9998, respectively (Fig. S2B).

Isolation of bacterial and fungal strains.

Luria-Bertani (LB) agar (peptone 10 g/liter, NaCl 10 g/liter, yeast extract 5 g/liter, and agar 20 g/liter) and de Man-Rogosa-Sharpe (MRS) agar (CM1175; Oxoid Thermo Fisher, UK) were used for the isolation of bacteria. Potato dextrose agar (PDA; potato extract 6 g/liter, glucose 20 g/liter, chloramphenicol 0.2 g/liter, and agar 20 g/liter) was used for the isolation of fungi. For the isolation of lactic acid bacteria, 10 g of fermented grains was mixed with 90 ml of sterile saline solution (0.85% [wt/vol] sodium chloride) and homogenized in an anaerobic system (Model 1029 Forma Anaerobic System; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 2 min. For the isolation of other bacteria and fungi, fermented grain samples (10 g) were homogenized in sterile saline solution (0.85% [wt/vol] sodium chloride, 90 ml) in a 30°C shaking incubator for 30 min at 200 rpm. Samples (1.0 ml) from the homogenate were serially diluted 10-fold in sterile saline solution, and 100 μl from the dilutions was spread on the surface of the LB, MRS, and PDA plates, and then incubated at 30°C for 48 h. LB and PDA plates were incubated under aerobic (in air) conditions, whereas MRS plates were incubated under anaerobic conditions.

Genomic DNA of the single isolated strains was extracted according to the instruction of the TIANamp DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). For bacteria, 16S rRNA genes were amplified using the universal primer sets 27F and 1492R as described previously (38). For fungi, the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region was amplified with primers ITS1 and ITS4 as described previously (39). DNA sequencing of the PCR products was conducted by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). After a BLAST search against the sequences (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), the results were used for the identification of isolates.

Anti-Candida activity by agar diffusion assay.

The relationships between C. humilis and the isolate microbes were tested by modified agar diffusion assay (40). Briefly, a 5-mm sterile filter paper was put in the middle of a sorghum extract agar (17) plate which had been covered uniformly with 100 μl of C. humilis (107 CFU per milliliter). A 10-μl aliquot of culture broth of the isolates was added to the filter paper. Growth inhibition was verified after incubation at 30°C for 48 h.

Statistical analysis.

Metastats software was used to determine the discrepant OTUs between the two batches of fermentation (41). PCA of metabolites was analyzed via Unscrambler v9.7 (Camo, Trondheim, Norway). CCA was conducted based on metabolites and the bacterial and fungal communities via the vegan package in R (http://vegan.r-forge.r-project.org/). To analyze the relationships among microbial communities, we calculated all possible Spearman's rank correlations between the abundant genera (with average abundance of >1%). Only significant correlations (P < 0.05, with false discovery rate correction) were considered valid correlations. A network was created with Gephi (Web Atlas, Paris, France) to sort through and visualize the correlations (42). To predict the sources of microbial communities in fermented grain samples, SourceTracker (v0.9.8) was used with the default parameters (12). Fermented grain A and B samples (day 0) were set as sink. Daqu and the environmental samples (tools, indoor ground, and outdoor ground) were set as sources.

Accession number(s).

All sequences generated were submitted to the DDBJ database under the accession number PRJDB6509.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (grants 31530055 and 31501469), the National Key R&D Program of China (grant 2016YFD0400503), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (grant BK20150143), the Program of Introducing Talents of Discipline to Universities (111 Project) (grant 111-2-06), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (grant JUSRP11537), the Jiangsu Province “Collaborative Innovation Center for Advanced Industrial Fermentation” industry development program, and the Postgraduate Research & Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (grant KYLX_1151).

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02369-17.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bokulich NA, Ohta M, Lee M, Mills DA. 2014. Indigenous bacteria and fungi drive traditional kimoto sake fermentations. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5522–5529. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00663-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bokulich NA, Mills DA. 2013. Facility-specific “house” microbiome drives microbial landscapes of artisan cheesemaking plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:5214–5223. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00934-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokulich NA, Collins TS, Masarweh C, Allen G, Heymann H, Ebeler SE, Mills DA. 2016. Associations among wine grape microbiome, metabolome, and fermentation behavior suggest microbial contribution to regional wine characteristics. mBio 7:e00631-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00631-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alfonzo A, Miceli C, Nasca A, Franciosi E, Ventimiglia G, Di Gerlando R, Tuohy K, Francesca N, Moschetti G, Settanni L. 2017. Monitoring of wheat lactic acid bacteria from the field until the first step of dough fermentation. Food Microbiol 62:256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2016.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Du H, Xu Y. 2017. Source tracking of prokaryotic communities in fermented grain of Chinese strong-flavor liquor. Int J Food Microbiol 244:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokulich NA, Bergsveinson J, Ziola B, Mills DA. 2015. Mapping microbial ecosystems and spoilage-gene flow in breweries highlights patterns of contamination and resistance. Elife 4:e04634. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang HY, Zhang XJ, Zhao LP, Xu Y. 2008. Analysis and comparison of the bacterial community in fermented grains during the fermentation for two different styles of Chinese liquor. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 35:603–609. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0323-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li XR, Ma EB, Yan LZ, Meng H, Du XW, Zhang SW, Quan ZX. 2011. Bacterial and fungal diversity in the traditional Chinese liquor fermentation process. Int J Food Microbiol 146:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin G, Zhu Y, Xu Y. 2017. Mystery behind Chinese liquor fermentation. Trends Food Sci Tech 63:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.02.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li XR, Ma EB, Yan LZ, Meng H, Du XW, Quan ZX. 2013. Bacterial and fungal diversity in the starter production process of Fen liquor, a traditional Chinese liquor. J Microbiol 51:430–438. doi: 10.1007/s12275-013-2640-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao W, Fan W, Xu Y. 2014. Characterization of the key odorants in light aroma type Chinese liquor by gas chromatography-olfactometry, quantitative measurements, aroma recombination, and omission studies. J Agric Food Chem 62:5796–5804. doi: 10.1021/jf501214c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knights D, Kuczynski J, Charlson ES, Zaneveld J, Mozer MC, Collman RG, Bushman FD, Knight R, Kelley ST. 2011. Bayesian community-wide culture-independent microbial source tracking. Nat Methods 8:761–763. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang HY, Gao YB, Fan QW, Xu Y. 2011. Characterization and comparison of microbial community of different typical Chinese liquor Daqus by PCR-DGGE. Lett Appl Microbiol 53:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiu L, Kunliang G, Hongxun Z. 2012. Determination of microbial diversity in Daqu, a fermentation starter culture of Maotai liquor, using nested PCR-denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. World J Microbiol Biotechnol 28:2375–2381. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1045-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng XW, Yan Z, Han BZ, Zwietering MH, Samson RA, Boekhout T, Robert Nout MJ. 2012. Complex microbiota of a Chinese “Fen” liquor fermentation starter (Fen-Daqu), revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods. Food Microbiol 31:293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng XW, Yan Z, Nout MJ, Smid EJ, Zwietering MH, Boekhout T, Han JS, Han BZ. 2014. Microbiota dynamics related to environmental conditions during the fermentative production of Fen-Daqu, a Chinese industrial fermentation starter. Int J Food Microbiol 182:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong Y, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Xu Y. 2014. In situ analysis of metabolic characteristics reveals the key yeast in the spontaneous and solid-state fermentation process of Chinese light-style liquor. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:3667–3676. doi: 10.1128/AEM.04219-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doyle CJ, Gleeson D, O'Toole PW, Cottera PD. 2017. Impacts of seasonal housing and teat preparation on raw milk microbiota: a high-throughput sequencing study. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02694-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02694-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao C, Lv X, Fu J, He C, Hua H, Yan Z. 2016. In vitro inhibitory activity of probiotic products against oral Candida species. J Appl Microbiol 121:254–262. doi: 10.1111/jam.13138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabbene O, Kalai L, Slimene IB, Karkouch I, Elkahoui S, Gharbi A, Cosette P, Mangoni ML, Jouenne T, Limam F. 2011. Anti-Candida effect of bacillomycin D-like lipopeptides from Bacillus subtilis B38. FEMS Microbiol Lett 316:108–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2010.02199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang WX, Qiao ZW, Shigematsu T, Tang YQ, Hu C, Morimura S, Kida K. 2005. Analysis of the bacterial community in Zaopei during production of Chinese Luzhou-flavor liquor. J Inst Brewing 111:215–222. doi: 10.1002/j.2050-0416.2005.tb00669.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang L, Wang YY, Wang DQ, Xu J, Yang F, Liu G, Zhang DY, Feng Q, Xiao L, Xue WB, Guo J, Li YZ, Jin T. 2015. Dynamic changes in the bacterial community in Moutai liquor fermentation process characterized by deep sequencing. J Inst Brewing 121:603–608. doi: 10.1002/jib.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen B, Wu Q, Xu Y. 2014. Filamentous fungal diversity and community structure associated with the solid state fermentation of Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor. Int J Food Microbiol 179:80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacques N, Sarilar V, Urien C, Lopes MR, Morais CG, Uetanabaro APT, Tinsley CR, Rosa CA, Sicard D, Casaregola S. 2016. Three novel ascomycetous yeast species of the Kazachstania clade, Kazachstania saulgeensis sp. nov., Kazachstaniaserrabonitensis sp. nov. and Kazachstania australis sp. nov. Reassignment of Candida humilis to Kazachstania humilis f.a. comb. nov. and Candida pseudohumilis to Kazachstania pseudohumilis f.a. comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Micr 66:5192–5200. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gullo M, Romano AD, Pulvirenti A, Giudici P. 2003. Candida humilis—dominant species in sourdoughs for the production of durum wheat bran flour bread. Int J Food Microbiol 80:55–59. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.De Vuyst L, Harth H, Van Kerrebroeck S, Leroy F. 2016. Yeast diversity of sourdoughs and associated metabolic properties and functionalities. Int J Food Microbiol 239:26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Q, Chen L, Xu Y. 2013. Yeast community associated with the solid state fermentation of traditional Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor. Int J Food Microbiol 166:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tang K, Ma L, Han YH, Nie Y, Li JM, Xu Y. 2015. Comparison and chemometric analysis of the phenolic compounds and organic acids composition of Chinese wines. J Food Sci 80:20–28. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.12691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Soergel DA, Dey N, Knight R, Brenner SE. 2012. Selection of primers for optimal taxonomic classification of environmental 16S rRNA gene sequences. ISME J 6:1440–1444. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ihrmark K, Bodeker IT, Cruz-Martinez K, Friberg H, Kubartova A, Schenck J, Strid Y, Stenlid J, Brandstrom-Durling M, Clemmensen KE, Lindahl BD. 2012. New primers to amplify the fungal ITS2 region—evaluation by 454-sequencing of artificial and natural communities. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 82:666–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2012.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pena AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. 2010. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods 7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. 2011. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Edgar RC. 2010. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics 26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Huber T, Dalevi D, Hu P, Andersen GL. 2006. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koljalg U, Larsson KH, Abarenkov K, Nilsson RH, Alexander IJ, Eberhardt U, Erland S, Hoiland K, Kjoller R, Larsson E, Pennanen T, Sen R, Taylor AF, Tedersoo L, Vralstad T, Ursing BM. 2005. UNITE: a database providing web-based methods for the molecular identification of ectomycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 166:1063–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fierer N, Jackson JA, Vilgalys R, Jackson RB. 2005. Assessment of soil microbial community structure by use of taxon-specific quantitative PCR assays. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:4117–4120. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.4117-4120.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ritalahti KM, Amos BK, Sung Y, Wu Q, Koenigsberg SS, Loffler FE. 2006. Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:2765–2774. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2765-2774.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rochelle PA, Fry JC, Parkes RJ, Weightman AJ. 1992. DNA extraction for 16S rRNA gene analysis to determine genetic diversity in deep sediment communities. FEMS Microbiol Lett 100:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics, p 315–322. In Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ (ed), PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dimkić I, Živković S, Berić T, Ivanović Ž, Gavrilović V, Stanković S, Fira D. 2013. Characterization and evaluation of two Bacillus strains, SS-12.6 and SS-13.1, as potential agents for the control of phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi. Biol Control 65:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M. 2009. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Comput Biol 5:e1000352. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. 2009. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. ICWSM 8:361–362. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.