Summary

Impaired immune responsiveness is a significant barrier to vaccination of neonates. By way of example, the low seroconversion observed following influenza vaccination has led to restriction of its use to infants over 6 months of age, leaving younger infants vulnerable to infection. Our previous studies using a non‐human primate neonate model demonstrated that the immune response elicited following vaccination with inactivated influenza virus could be robustly increased by inclusion of the Toll‐like receptor agonist flagellin or R848, either delivered individually or in combination. When delivered individually, R848 was found to be the more effective of the two. To gain insights into the mechanism through which these adjuvants functioned in vivo, we assessed the initiation of the immune response, i.e. at 24 hr, in the draining lymph node of neonate non‐human primates. Significant up‐regulation of co‐stimulatory molecules on dendritic cells could be detected, but only when both adjuvants were present. In contrast, R848 alone could increase the number of cells in the lymph node, presumably through enhanced recruitment, as well as B‐cell activation at this early time‐point. These changes were not observed with flagellin and the dual adjuvanted vaccine did not promote increases beyond those observed with R848 alone. In vitro studies showed that R848 could promote B‐cell activation, supporting a model wherein a direct effect on neonate B‐cell activation is an important component of the in vivo potency of R848 in neonates.

Keywords: B cell, dendritic cell, influenza, neonate, nonhuman primate, vaccination

Abbreviations

- AGM

African green monkey

- AxLN

axillary lymph node

- DCs

dendritic cells

- flg

flagellin

- NHP

non‐human primate

- TLR

Toll‐like receptor

Introduction

The impaired immune response in infants makes the development of effective vaccine strategies particularly challenging. Achieving protective levels of immunity is hampered by IgG antibody responses that are reduced in both level and affinity through the first year of life.1, 2 In human neonates there is evidence supporting a generalized defect in T‐cell responsiveness,2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 which may hinder antibody production as a result of a compromised CD4+ response. Finally, neonates appear to have a heightened regulatory T‐cell response,9, 10 adding another barrier to the generation of an adaptive immune response. Vaccines that can work effectively in neonates must be capable of overcoming these appreciable obstacles.

Significant effort has been expended in harnessing the power of Toll‐like receptor (TLR) agonists to improve vaccines with promising results (for review see ref. 11). We and others have begun to explore this as a mechanism to overcome the immune deficits present in neonates.12, 13, 14, 15 TLRs belong to a family of receptors that recognize molecules derived from viral, bacterial and fungal pathogens as well as endogenous molecules that signal danger.16, 17 This family of receptors is broadly distributed on innate and adaptive immune cells and as a result multiple cell types including T cells, B cells and dendritic cells (DCs) can be modulated by these ligands. The representation of individual receptors differs with cell type and, hence, the choice of ligand will determine the population activated.

A critical target for generation of an adaptive immune response is DCs, as these cells play a central role in the generation of immunity as initiators of T‐cell activation. Results from DCs generated from human cord blood reveal that these cells are capable of responding to TLR engagement, although they are impaired compared with cells derived from adults.18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Of note, these studies were performed with in vitro differentiated cells, which are thought to resemble dermal‐like CD1a+ conventional DCs24 and therefore may not reflect other subsets. Not surprisingly, there is a paucity of data from in vivo differentiated human neonate DCs. The suboptimal responsiveness reported in neonate DCs is manifest as a decrease in the expression of co‐stimulatory molecules and a reduction in interleukin‐12 (IL‐12). These findings led us to hypothesize that enhancing DC maturation through increasing the strength of signalling through TLR would promote greater activation of T cells following vaccination. In addition, the ability of TLR agonists to act directly on T or B cells would further facilitate immune activation.

We chose two TLR agonists, the TLR5 ligand flagellin and the TLR7/8 ligand R848, for assessment as effective adjuvants in the context of neonate vaccination. R848 (or its closely related analogue 3M‐012) has shown promise in adult models of vaccination.25, 26, 27, 28 It is reported to increase cell‐mediated immune responses when incorporated into hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)25 or HIV gag26 protein vaccines. Further, R848 can induce robust antibody production.27, 28 Increased antibody production may occur through indirect effects of R848 on CD4+ T cells or directly through its ability to activate B cells.29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 The capacity for R848 to signal through TLR8 in addition to TLR7 is an attractive attribute given reports that TLR8 agonists suppress regulatory T cells39 in addition to inducing robust T helper type 1‐biasing cytokines in neonatal antigen‐presenting cells.40 Hence, R848 has the potential to overcome two obstacles associated with neonates, T helper type 2 skewing and increased regulatory T cells.

The other agonist we explored, flagellin (flg), is also a potent adjuvant for the induction of antibody responses (for review see refs 41, 42). The potency of flagellin as an adjuvant is in part due to its ability to induce activation of DCs.43 In addition, TLR5 agonists have the potential to act directly on primate T cells, promoting increases in both proliferation and cytokine production.41, 44, 45, 46 Importantly, there are data supporting the effectiveness of this molecule for activation of T cells from neonates.44 Finally, flagellin effectively recruits T and B cells to secondary lymphoid sites, promoting more efficient activation of relevant immune effectors.45, 47, 48 Hence, this adjuvant has the capacity to facilitate the generation of an immune response through its action on multiple cell types.

In our studies we have used a non‐human primate (NHP) model to assess the potential for flagellin or R848 to serve as effective activators of the immune system in the context of neonate vaccination against influenza.12, 13, 14 We developed an R848‐adjuvanted vaccine wherein R848 was directly conjugated to the influenza virion. We chose this approach because of the growing number of reports showing that direct conjugation of a TLR agonist to an antigen improves responses following vaccination (for review see ref. 49). Vaccination of neonate NHP resulted in improved immune responses when either flagellin or R848 were included as adjuvants,13, 14 although R848 was superior to flagellin. The goal of the studies reported here was to understand at a mechanistic level how these adjuvants were working to enhance immunity in the context of the neonate. To address this critical question, we isolated the draining lymph nodes from vaccinated NHP neonates at 24 hr post vaccination. Antigen‐presenting cell number and maturation were assessed, as were the number and activation of T‐cell and B‐cell populations. Our results support a direct effect on B cells as a component of the improved in vivo activity of R848.

Materials and methods

Vaccination

African green monkey (AGM) infants (Caribbean‐origin Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) used in this study were housed at the Vervet Research Colony at Wake Forest School of Medicine. At 3–5 days of age, infants were vaccinated intramuscularly with 45 μg of 0·74% formaldehyde‐inactivated A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 [H1N1] (PR8) virus mixed with 10 μg of flagellin (flg) or a biologically inactive hypervariable region construct (m229)47, 50 or inactivated PR8 conjugated with R848 (IPR8‐R848). Flagellin and IPR8‐R848 were also co‐administered. Control animals received PBS. For the IPR8‐R848 conjugate vaccine,13 an amine derivative of R848 (hereon referred to as R848) was linked to SM(PEG)4 (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) by incubation in DMSO for 24 hr at 37°. R848‐SM(PEG)4 was then incubated with influenza virus that had been reduced to generate free thiol groups (IPR8‐R848). Unconjugated R848 was removed by extensive dialysis. This construct was then inactivated by treatment with 0·74% formaldehyde for 1 hr at 37°, followed by dialysis. Successful conjugation was assessed by differential stimulation of RAW264.7 cells (Wake Forest Comprehensive Cancer Center Cell and Viral Vector Core Laboratory) following incubation with similar doses (based on protein content) of R848‐conjugated versus non‐conjugated vaccine. Flagellin from Salmonella enteritidis was prepared as previously described.50 Endotoxin and nucleic acids were removed using an Acrodisc Mustang Q capsule (Pall Corporation, New York, NY) and purified proteins were extensively dialysed against PBS. All injections were delivered intramuscularly into the deltoid muscle (500 μl volume). Newborns received the vaccine in the right arm and PBS in the left. Five animals were included in each group with the exception of the IPR8‐R848 group, which had six. An additional animal was added to this group because of the partial loss of a tissue sample during processing that prevented calculation of cell number.

Animal approval

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Wake Forest School of Medicine. The WFSM animal care and use protocol adhered to the US Animal Welfare Act and Regulations.

Analysis of axillary lymph node cells

Twenty‐four hours following vaccination, the right and left axillary lymph nodes (AxLN) were isolated by biopsy. Tissues were processed through a sterile 70‐μm filter to obtain a single‐cell suspension. The single‐cell suspensions were digested with Collagenase D from Clostridium histolyticum (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at 1 mg/ml for 1 hr at 37°. Cells were washed and stained with Zombie Violet (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) to exclude dead cells. For DC and monocyte analysis, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 488‐conjugated CD11b (Clone M1/70; BioLegend), phycoerythrin‐conjugated CD11c (Clone S‐HCL‐3; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), peridinin chlorophyll protein‐Cy5.5‐conjugated CD14 (Clone M5E2; BioLegend), phycoerythrin‐Cy7‐conjugated CD80 (Clone L307.4; BD Bioscience) and Brilliant Violet 510‐conjugated CD86 (Clone 2331; BD Bioscience). Activated T and B cells were assessed by staining with CD3 Biotin (Clone 10D12; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) followed by Avidin‐BV510, peridinin chlorophyll protein‐Cy5.5‐conjugated CD4 (Clone L200; BD Bioscience), phycoerythrin‐conjugated CD8β (Clone 2ST8.5H7; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA), allophycocyanin‐conjugated CD69 (Clone FN50; BioLegend) and FITC‐conjugated CD20 (Clone 2H7; BioLegend). Samples were acquired on a BD FACS Canto II and analysed with bd diva software (BD Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA).

Cytokine production by RT‐PCR in AxLN cells

Total RNA was isolated from pelleted AxLN cells using an RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III First Strand Synthesis System for RT‐PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Quantitative PCR was performed with a TaqMan PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The TaqMan primers and probes used are as follows: IL‐10 forward (TTGCTGGAGGACTTTAAGGGTTAC), reverse (TCAGCTTGGGGCATAACC) and probe (TTGCCAAGCCTTGTCTGAGATGATCCA); tumour necrosis factor‐α forward (ATGGCAGAGAGGAGGTTGACC), reverse (TACTCCCAGGTCCTCTTCA), and probe (CAGCCGCATCGCCGTCTCCT); interferon‐β forward (GCCTCAAGGACAGGATGAACTT), reverse (CGTCCTCCTTCTGGAACTGC), and probe (CATCCCTGAGGAAATTAAGCAGCCGC); CXCL10 forward (CCAAGTCAATTTTGTCCACATGTT), reverse (CAGACACCTCTTCTCACCCTTCTT), and probe (AGATCATTGCTACAATGAA); IL‐6 forward (TGCTTTCACACATGTTACTCCTGTT), reverse (CATCCTCGACGGCATCTCA), and probe (ATGTCTCCTTTCTCAGGGC); and β‐actin forward (GCTGCCCTGAGGCTCTCTT), reverse (TGATGGAGTTGAAGGTAGTTTCATG), and probe (TTCCTGGGCATGGAGT). The TaqMan probe for IL‐12B was from Applied Biosystems. β‐Actin was used to normalize gene expression across samples.

Analysis of splenic B‐cell activation by TLR ligands

Spleens were isolated from four newborn AGM (4–5 days of age) at necropsy. Single‐cell suspensions were prepared from mechanically dispersed tissue and frozen for future study. Cells were thawed by placement in a 37° water bath for 10 min. This was followed by slow dilution with warm medium containing DNase I (0·1 mg/ml, StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). Recovered cells were > 90% viable. B cells were enriched using Miltenyi CD20‐conjugated microbeads as per the manufacturer's instructions with the modification of doubling the amount of beads due to the very high percentage of B cells present in the spleen. Then, 5 × 105 isolated cells were cultured in round‐bottom plates for 24 hr in the presence of the amine derivative of R848 used in our vaccination study (5 or 25 μg/ml), flagellin (100 or 500 nm), or the combination of the two adjuvants (5 μg/ml R848 + 100 nm flagellin or 25 μg/ml R848 + 500 nm flagellin). B‐cell activation was assessed by measuring CD86 expression.

Statistical analysis

Significance was determined by a one‐way analysis of variance test using graphpad prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA.

Results

IPR8‐conjugated R848 results in an increase in the number of cells in the draining LN at 24 hr following vaccination

To determine the effect of the TLR agonists R848 and flagellin on the immune response following vaccination with inactivated influenza virus (IPR8), newborn AGM (3–5 days old) were vaccinated in the right arm with inactivated PR8 together with flagellin (IPR8 + flg), IPR8 conjugated to R848 (IPR8‐R848), IPR8 conjugated to R848 plus flagellin (IPR8‐R848 + flg), or IPR8 plus the inactive flagellin protein m229 (IPR8 + m229). The lack of stimulatory activity of m229 was demonstrated by the failure to increase CD40 on THP‐1 cells or tumour necrosis factor‐α production in RAW264.7 cells (Fig. S1). All newborn animals received PBS injections in the left arm. Twenty‐four hours post vaccination, the left and right AxLN were isolated by biopsy and cells were isolated by dissociation in the presence of collagenase D.

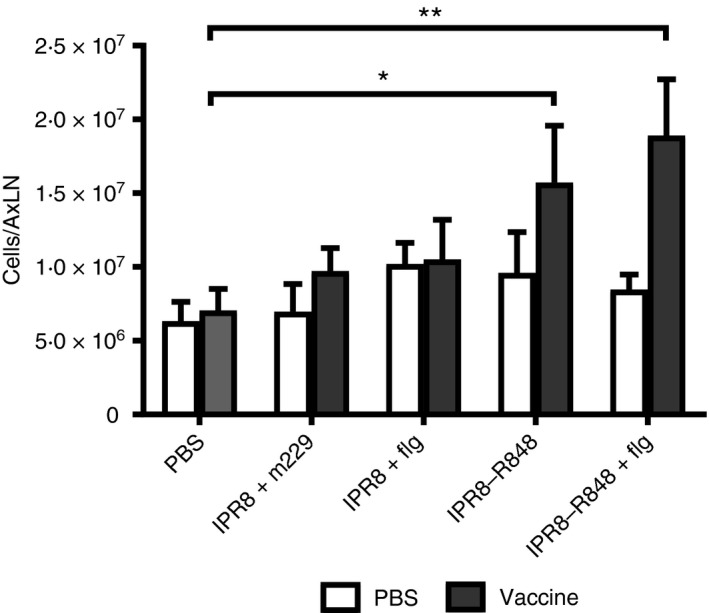

No differences were observed in the total number of cells obtained from AxLN of newborns vaccinated with IPR8 + m229 or IPR8 + flg compared with newborns that received PBS (Fig. 1). However, the AxLN isolated from newborns that received an R848‐conjugated vaccine (IPR8‐R848 or IPR8‐R848 + flg) had a significantly higher number of cells compared with non‐vaccinated animals. Increased recruitment was restricted to the LN draining the vaccine site (vaccine) and was not observed in the axillary node draining the PBS injection site (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The presence of conjugated R848 results in an increase in the number of cells in the draining lymph node. Neonate African green monkeys were injected intramuscularly in the right arm with IPR8 + m229, IPR8 + flg, IPR8‐R848, IPR8‐R848 + flg, or PBS. All infants received PBS in the left arm. Twenty‐four hours later, draining axillary lymph nodes were isolated, mechanically dissociated, incubated with collagenase D, and subsequently quantified. Each group contained five animals. Cell numbers (average ± SEM) in vaccinated neonates were compared with neonates that received PBS. Significance was determined using a two‐way analysis of variance. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·005.

R848‐containing vaccines fail to promote an increase in DC and macrophages in the draining LN at 24 hr post vaccination

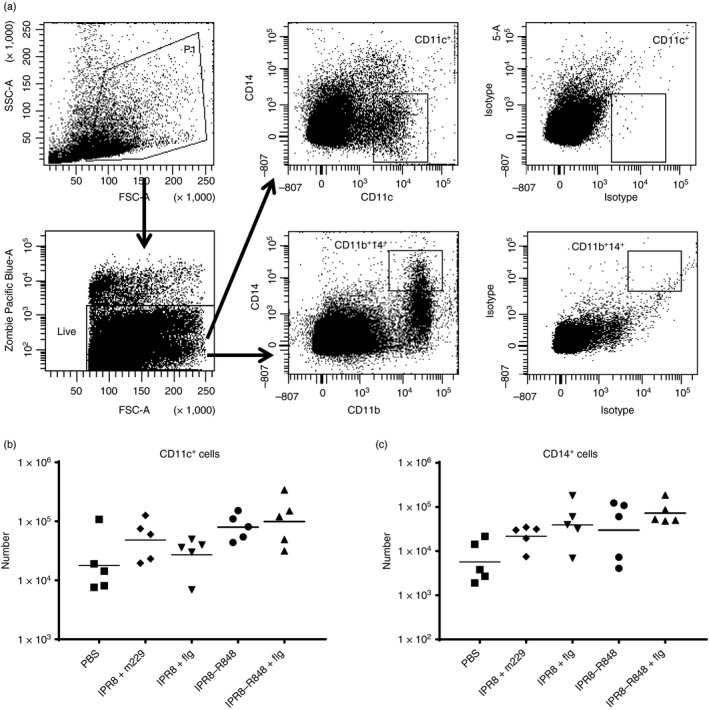

Initiation of a T‐cell response is dependent on presentation by professional APC, most often DC. However, macrophages may also serve in this capacity under some circumstances.51 Hence, we determined how the presence of the adjuvants impacted the recruitment of DCs and macrophages to the LN. Dendritic cells were identified by the expression of CD11c and macrophages by positive staining for CD11b and CD14. Representative plots and gating strategy are shown in Fig. 2(a). None of the adjuvanted vaccines resulted in a significant increase in the number of DCs or macrophages compared with the non‐adjuvanted vaccine IPR8 + m229 or non‐vaccinated newborns (Fig. 2b,c). As would be expected, there were no differences in the numbers of cells in the LN draining the PBS injection site (see Supplemetary material, Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Adjuvanted IPR8 does not increase the number of dendritic cells (DCs) present in the draining axillary lymph node. Cells isolated from the vaccine draining lymph nodes of the neonates were stained with the live/dead discriminator Zombie Violet and antibodies to CD11c, CD14 and CD11b (or their respective isotypes). Representative primary data are shown in (a) and the total number and geometric mean of CD11c+ cells (DCs) and CD14+ CD11b+ (macrophages) for each animal are shown in (b) and (c), respectively.

The combination of R848 and flagellin results in increased maturation of DCs in the draining LN at 24 hr post vaccination

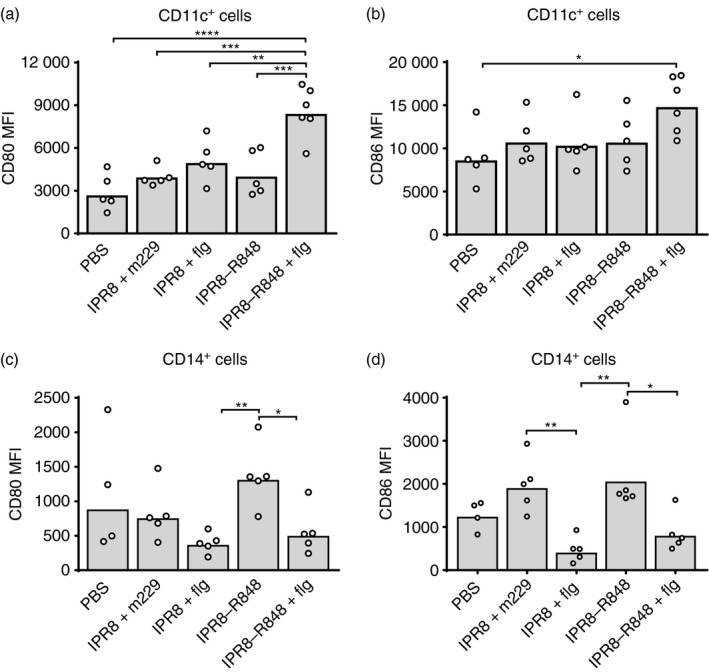

We next examined whether the presence of the adjuvants impacted the maturation of DCs and macrophages, as measured by the level of CD80 and CD86. Data showing the level of CD80 and CD86 on DCs and macrophages from individual animals is shown in Fig. 3. The presence of either R848 or flagellin alone had minimal effects on the expression of CD80 and CD86 on DCs. Only DCs from newborns vaccinated with the dual‐adjuvanted vaccine (IPR8‐R848 + flg) exhibited significantly higher levels of these two markers at the population level (Fig. 3a,b). These data show that adjuvanting with either flagellin or R848 alone did not induce significant increases in DC maturation. This is in contrast to the maturation observed when both adjuvants were included in the vaccine.

Figure 3.

Increased maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) in the draining lymph node requires the combination of R848 and flagellin adjuvants. DCs and macrophages identified as described in Fig. 2 were stained with antibodies to CD80 and CD86. The mean fluorescence index (MFI) of CD80 and CD86 within the DCs (a and b) and monocyte (c and d) populations for individual animals are shown. The average is represented by the bar. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·005, ***P < 0·0005, ****P < 0·0001.

The expression of CD80 and CD86 on macrophages exhibited a different pattern. The presence of flagellin was unexpectedly associated with reduced expression of these markers compared with those receiving the R848‐adjuvanted vaccine (Fig. 3c,d). Although not significant, as shown above (Fig. 2), there was a trend towards an increase in macrophages following vaccination with IPR8 + flg. It is therefore tempting to speculate that flagellin delivered alone may recruit macrophages that have lower expression of CD80 and CD86 to the AxLN.

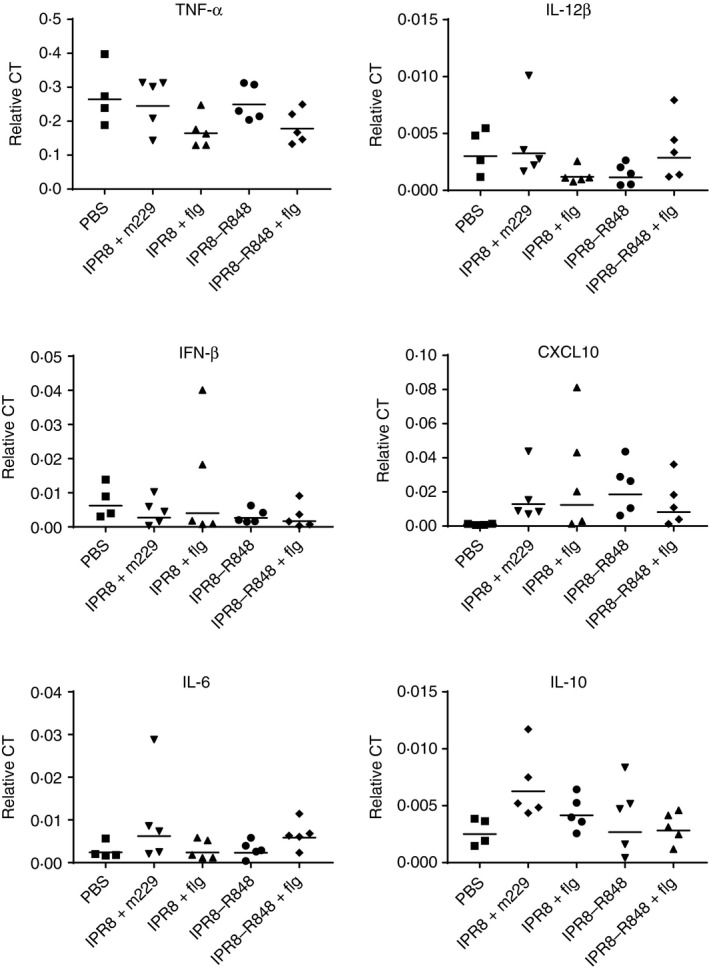

Analysis of cytokine mRNA levels in the AxLN following vaccination

Given the lack of association of DC maturation or number with the increased immune response in neonates observed following vaccination with IPR8‐R848 or IPR8 + flg vaccines,13, 14 we tested the hypothesis that the cytokine milieu differed following delivery of the adjuvants. levles of mRNA for the pro‐inflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor‐α, IL‐6 and CXCL10 were measured in the AxLN of the vaccinated newborns. We also assessed IL‐12β and interferon‐β given their reported role in T helper type 1 differentiation and/or acquisition of effector function in CD8+ T cells.52, 53 Finally, we determined whether there were changes in the anti‐inflammatory cytokine IL‐10, which has been reported to be over‐expressed in infant DCs.22 No consistent adjuvant‐associated increase in any of the assessed pro‐inflammatory cytokines was observed (Fig. 4). There was a trend towards a decrease in IL‐10 in newborns receiving the adjuvanted vaccines compared with newborns that received IPR8 + m229, although this did not meet statistical significance.

Figure 4.

The presence of adjuvants does not result in a significant increase in pro‐inflammatory cytokines in the draining lymph nodes at 24 hr. A sample of the draining axillary lymph nodes (AxLN) was lysed and RNA was isolated for RT‐PCR analysis. Data have been normalized to β‐actin. The geometric mean is shown for each group.

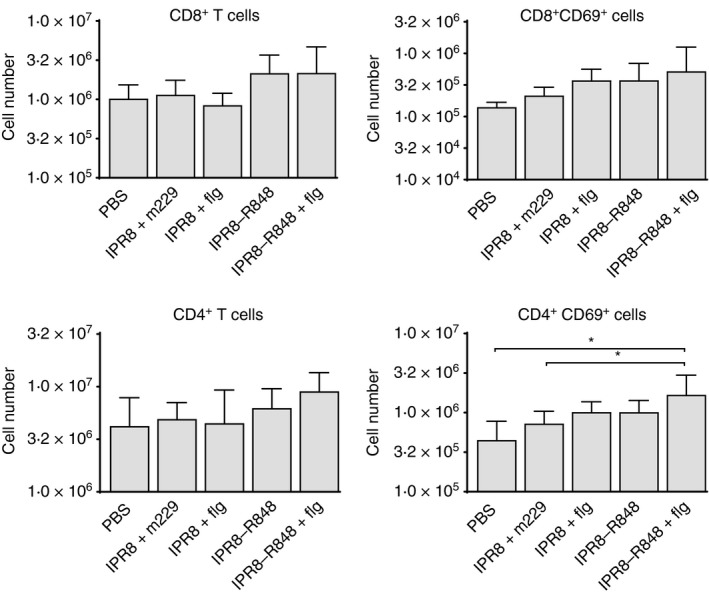

Analysis of T‐cell activation as a result of vaccination

The lack of increased antigen‐presenting cell maturation or number when R848 or flagellin alone was included in the vaccine was surprising given the potent effects of the adjuvants on adaptive immune responses observed in vivo in our previous studies.13, 14 In view of the expression of TLR5 and TLR7/8 on T cells,29, 30, 31 we asked whether there was evidence of increased recruitment or direct activation of T cells that was associated with the presence of the adjuvants. We first assessed the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the draining AxLN at 24 hr post vaccination. The presence of activated cells was measured by CD69 expression. There was no significant increase in the total number of CD8+ or CD4+ T cells or the number of activated CD8+ T cells in any of the vaccinated groups, although there was a trend towards an increased number of activated CD8+ cells in the presence of adjuvant (Fig. 5, upper panels). As would be expected, there was also no significant increase in the number of these cells in the LN draining the PBS injection site (see Supplementary material, Fig. S3).

Figure 5.

The combination of R848 and flagellin results in a modest increase in CD69+ CD4+ T cells compared with the absence of adjuvants. Cells from the vaccine‐draining axillary lymph nodes of neonates were stained for CD4, CD8 and CD69 at 24 hr post vaccination. The total number (geometric mean ± SD) of CD4+ and CD8+ cells was determined as was the number of each subset expressing CD69. For analysis cells were pre‐gated on live cells by forward and side scatter. *P < 0·05.

Although the adjuvants did not impact the number of CD4+ T cells found in newborns, there was a significant increase in CD69+ CD4+ cells in the draining LN of the dual‐adjuvanted vaccine compared with both PBS‐vaccinated and IPR8 + m229‐vaccinated animals (Fig. 5, bottom panels). Vaccination with IPR8‐R848 + flg induced a 3·7‐fold increase compared with the PBS group and a 2·3‐fold increase compared with the IPR8 + m229 group. No other vaccine resulted in a significant increase in cell number. Hence, as with DC maturation, the combined presence of the adjuvants resulted in the most robust activation of T cells at 24 hr post‐vaccination, although this was restricted to the CD4+ subset.

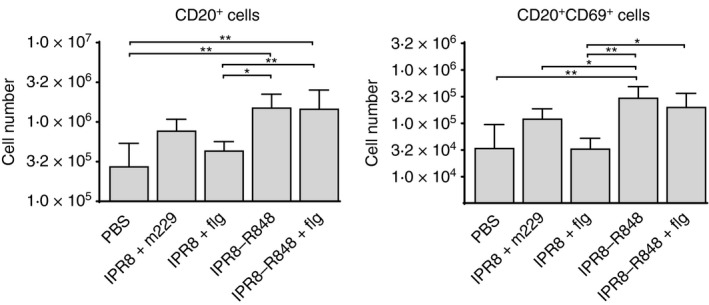

Increased B‐cell activation is associated with vaccines containing conjugated R848

We next evaluated B cells in the draining LN at 24 hr post vaccination. There was no significant increase in CD20+ cells in the AxLN of newborns vaccinated with IPR8 + m229 or IPR8 + flg compared with PBS controls (Fig. 6a). In contrast, the number of CD20+ cells was significantly increased in newborns that received IPR8‐R848 (5·5‐fold) or IPR8‐R848 + flg (5·3‐fold) compared with PBS. The number was also significantly increased when compared with IPR8 + flg vaccinated newborns (IPR8‐R848 increased 3·5‐fold and IPR8‐R848 + flg increased 3·3‐fold (Fig. 6a). When activated B cells were assessed, we saw a corresponding significant increase (7·1‐fold) in CD69+ CD20+ cells in newborns vaccinated with IPR8‐R848 compared with animals that received IPR8 + flg (Fig. 6b). As with CD20+ cell number, there was no further increase in newborns that received both flagellin and R848 (Fig. 6b). These increases were restricted to the vaccine draining LN as no significant difference in B cells (total or CD69+) was observed in the LN draining the PBS injection site of animals vaccinated with IPR8‐R848 or IPR8‐R848 + flg (see Supplementary material, Fig. S3). These data support the potential for R848 to directly activate B cells in the newborns.

Figure 6.

The presence of conjugated R848 results in an increase in B‐cell number and activation in the draining lymph node. Cells from the vaccine‐draining axillary lymph node of neonates were stained for CD20 and CD69 at 24 hr post vaccination. The total number (average ± SEM) of CD20+ and CD20+ CD69+ cells was determined. For analysis cells were pre‐gated on live cells by forward and side scatter. *P < 0·05, **P < 0·005.

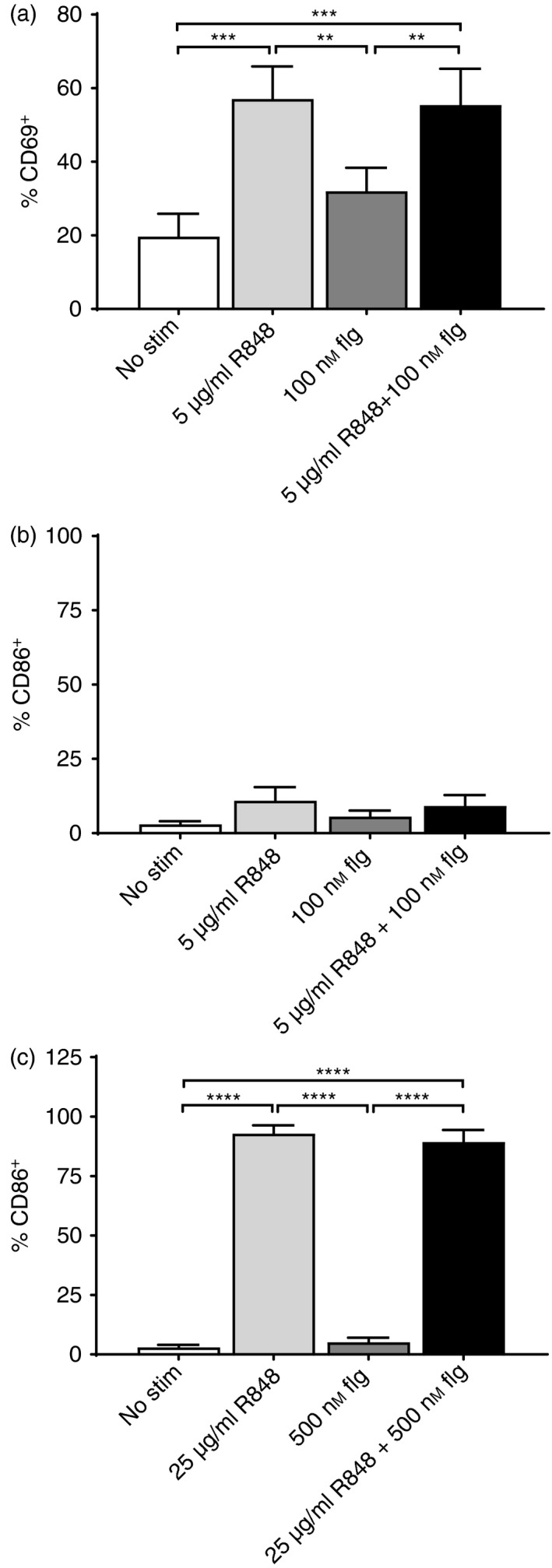

To test this hypothesis we isolated splenic B cells from four newborn AGM (4–5 days old) by positive selection with CD20+ microbeads. This approach resulted in populations that were ≥ 95% CD20+ (data not shown). B‐cell populations were stimulated for 24 hr with 5 μg/ml R848 and 100 nm flagellin, concentrations within the range of those previously reported to be stimulatory.32, 43 Flagellin did not significantly increase the percentage of cells that stained positive for CD69 (Fig. 7a). However, B cells from neonates cultured in the presence of R848 exhibited robust and significant increases in CD69+ cells compared with unstimulated cultures (Fig. 7a). We also evaluated CD86 expression as an indicator of activation. Surprisingly, we observed no increase in the expression of this molecule with any of the conditions tested (Fig. 7b). To determine whether R848 could induce up‐regulation of CD86 on neonate B cells, the concentration of each agonist was increased fivefold. The higher amount of flagellin still failed to increase CD86 expression. Of note, the flagellin was active as it induced up‐regulation of CD86 on NHP DCs (data not shown). However, in stark contrast to flagellin, the higher concentration of R848 induced robust up‐regulation of CD86, with 93% of the cells exhibiting positivity (Fig. 7c). This result supports the potential for R848 engagement of TLR7/8 on B cells to promote B‐cell activation in neonates and is therefore a likely contributor to the high level of antibody detected in our newborn NHP model.13, 14 .

Figure 7.

R848, but not flagellin, directly activates neonate B cells. CD20+ cells were isolated from the spleens of 4‐ to 5‐day‐old neonates by selection with CD20‐microbeads. Isolated CD20+ cells were cultured in the presence of 5 μg/ml R848 or 100 nm flagellin for 24 hr (a and b). Cells were stained with anti‐CD20 antibody together with anti‐CD69 (a) or anti‐CD86 (b). The average percent ± SEM of cells positive for each of the activation markers is shown. In (c), isolated CD20+ cells were stimulated with 25 μg/ml R848, 500 nm flagellin, or the combination for 24 hr and assessed for the expression of CD86. **P < 0·005, ***P < 0·0005, ****P < 0·0001.

Discussion

This study sought to understand how the presence of the TLR agonist flagellin or R848 impacted the early response in the draining LN of neonate NHP following vaccination with inactivated influenza virus. This analysis was prompted by our in vivo studies showing that these adjuvants could increase the antibody and T‐cell responses elicited by vaccination with IPR8.12, 13, 14 Although each of the adjuvants promoted an increased response in vivo, conjugated R848 was the more effective of the two, while at the same time having reduced systemic inflammation.13, 14 Surprisingly, we found that neither flagellin nor R848 had a detectable effect on DC number or function, although we did observe a significant increase in DC maturation when the adjuvants were co‐delivered. It was surprising that we failed to detect a significant increase in CD80/CD86 on DCs or cytokine production in neonates that received the singly adjuvanted vaccine. We had expected to see this effect given the increase in T‐cell and antibody responses detected in neonates that received these vaccines.13, 14 We acknowledge that using an NHP model limits the number of time‐points that can be examined and that the single adjuvant vaccines may have additional changes at a later time‐point. We chose 24 hr based on studies in mouse and NHP models where antigen could be detected at day 1 in the draining LN following administration at a distal site.54, 55, 56, 57, 58 With that said, adjuvants can induce detectable changes in co‐stimulatory molecules at this time as evidenced by the increases observed following co‐delivery of R848 and flagellin. In addition, our CD69 data support the presence of the vaccine antigen/adjuvants in the draining LN at this time. However, it remains possible that the single adjuvants are delayed in maturation. It is also possible that R848 or flagellin alone may result in maturation of a small subset of DCs that is below our detection limit in the readout. In contrast, analysis of B cells in the draining LN showed that inclusion of R848 was associated with a significant increase in recruitment and activation at early times, e.g. at 24 hr, following vaccination. In vitro studies confirmed the potent capacity for R848 to directly activate neonate B cells as demonstrated by its ability to promote increases in CD69 and CD86 expression. We propose direct activation of B cells by R848 as an important contributor to the increased immunogenicity observed in neonates with this vaccine.

The antibody response in infants is associated with a number of impairments including limited IgG responses to protein and polysaccharide antigens, limited persistence of IgG antibodies, and poor affinity maturation (for review see ref. 59). Although analyses of infant vaccination in humans have demonstrated a reduction in the quantity and quality of antibody produced, many questions remain with regard to our understanding of the regulation and function of human B cells from newborns. With that said, studies of human cord‐blood‐derived B cells have reported lower expression of molecules involved in B‐cell activation and maturation (CD40, CD80, CD86 and CD21),60, 61 which would be consistent with impaired responsiveness/function. However, there are also data from cord blood B cells showing relatively robust responses to IgM cross‐linking, suggesting that this pathway can respond when strong activation stimuli are present.62

There is evidence that TLR stimulation on B cells can contribute directly to antibody responses generated in the context of virus infection63, 64 as well as vaccines.65, 66 With regard to the latter, in a study using adult μMT mice reconstituted with MyD88‐sufficient or ‐deficient B‐cell populations, Kasturi et al.65 showed that TLR signalling on B cells was an important component of optimal antibody responses following vaccination with a model antigen (ovalbumin) nanoparticle vaccine. Further, in a recent study from Onodera et al.,66 an inactivated whole influenza virion vaccine was found to accelerate the recall antibody response to vaccination compared with a split‐virion vaccine. Follow‐up studies revealed that this was the result of an early TLR7‐dependent activation of memory B cells. These results are in agreement with the R848‐mediated activation observed here. As human B cells express TLR7,32, 33, 34, 35, 36 we would expect a similar effect in human infants administered R848‐containing vaccines. In our studies, flagellin failed to activate naive B cells. This is likely the result of an absence of TLR5 on naive NHP B cells, similar to what has been reported in mice and humans.33, 67, 68 The agreement between human and NHP TLR distribution/function, i.e. the failure of flagellin to activate neonate B cells coupled with the stimulatory capacity of R848, observed in our study provides continued support for the use of the NHP neonate model for TLR adjuvant testing.

Given the known ability of TLR to promote B‐cell activation in adults, Pettengill et al. assessed TLR expression in cord‐blood‐derived B cells. They found that many of the TLR, including TLR7, were expressed at levels similar to those in adult cells.36 Further, cord blood B cells responded to R848 stimulation by production of cytokines and up‐regulation of co‐stimulatory molecules, although certainly some of these responses were diminished compared with adult cells.36 The data presented here add further evidence for the ability of R848 to promote neonate B‐cell activation and suggest that this is an important contributor to the in vivo adjuvant function of R848 in this population.

CD69 is known to promote retention of lymphocytes in the LN through its binding to S1P1, promoting its internalization and thereby inhibiting lymphocyte egress.69 R848‐mediated increases in CD69 early in the immune response may facilitate B‐cell retention in the LN, thereby promoting differentiation, consistent with our data showing an increase in B‐cell number following vaccination with R848‐containing vaccines. It is important to keep in mind that the R848 in our vaccine construct is conjugated to the virus particle. This should target the enhancing effects of R848 primarily to virus‐specific cells as access to endosomal TLR7 in the B cells by IPR8‐R848 requires uptake.35

In summary, we show here that inclusion of adjuvants in an inactivated influenza virus vaccine administered to neonate NHP results in immune activation in the draining LN at 24 hr. The potent signal delivered by the combination of two TLR agonists, flagellin and R848, resulted in significant up‐regulation of co‐stimulatory molecules on DCs, whereas delivery of either of the adjuvants alone did not. The in vivo efficacy of R848 was associated with an increase in B‐cell activation observed at early times following vaccination, i.e. 24 hr. In vitro studies confirmed the ability of R848 to directly promote B‐cell activation. Hence, direct effects on neonate B cells may be an important attribute of the potency of R848 previously observed in vivo in this model.

Disclosures

The authors have no competing interests.

Supporting information

Figure S1. m229 does not have stimulatory activity.

Figure S2. There are no significant differences in the number of CD11c+ or CD14+ CD11b+ cells in the draining axillary lymph nodes of the PBS control arm of the vaccinated compared to non‐vaccinated (PBS) animals.

Figure S3. The number of total or activated T or B cells in the draining axillary lymph nodes of the PBS control arm of the vaccinated newborns is not significantly different from the number in the animals that did not receive vaccine (PBS).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Steven Mizel for provision of flagellin. We are appreciative of Dr Marlena Westcott and Dr Karen Haas for helpful comments related to this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 5R01AI098339 (to MAA‐M). The Vervet Research Colony is supported in part by P40 OD010965 (to MJJ). We acknowledge services provided by the Cell and Viral Vector Core, Synthetic Chemistry Core and Flow Cytometry Core Laboratories of the Wake Forest Comprehensive Cancer Center, supported in part by NCI P30 CA121291‐37.

References

- 1. Siegrist CA. The challenges of vaccine responses in early life: selected examples. J Comp Pathol 2007; 137(Suppl 1):S4–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall‐Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2004; 4:553–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Winkler S, Willheim M, Baier K, Schmid D, Aichelburg A, Graninger W et al Frequency of cytokine‐producing T cells in patients of different age groups with Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis 1999; 179:209–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xainli J, Baisor M, Kastens W, Bockarie M, Adams JH, King CL. Age‐dependent cellular immune responses to Plasmodium vivax Duffy binding protein in humans. J Immunol 2002; 169:3200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Randolph DA. The neonatal adaptive immune system. Neoreviews 2005; 6:e454–62. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhao Y, Dai ZP, Lv P, Gao XM. Phenotypic and functional analysis of human T lymphocytes in early second‐ and third‐trimester fetuses. Clin Exp Immunol 2002; 129:302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clerici M, DePalma L, Roilides E, Baker R, Shearer GM. Analysis of T helper and antigen‐presenting cell functions in cord blood and peripheral blood leukocytes from healthy children of different ages. J Clin Invest 1993; 91:2829–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Miscia S, Di Baldassarre A, Sabatino G, Bonvini E, Rana RA, Vitale M et al Inefficient phospholipase C activation and reduced Lck expression characterize the signaling defect of umbilical cord T lymphocytes. J Immunol 1999; 163:2416–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernandez MA, Puttur FK, Wang YM, Howden W, Alexander SI, Jones CA. T regulatory cells contribute to the attenuated primary CD8+ and CD4+ T cell responses to herpes simplex virus type 2 in neonatal mice. J Immunol 2008; 180:1556–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holbrook BC, Hayward SL, Blevins LK, Kock N, Aycock T, Parks GD et al Nonhuman primate infants have an impaired respiratory but not systemic IgG antibody response following influenza virus infection. Virology 2015; 476:124–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maisonneuve C, Bertholet S, Philpott DJ, De Gregorio E. Unleashing the potential of NOD‐ and Toll‐like agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111:12294–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holbrook BC, D'Agostino RB Jr, Parks GD, Alexander‐Miller MA. Adjuvanting an inactivated influenza vaccine with flagellin improves the function and quantity of the long‐term antibody response in a nonhuman primate neonate model. Vaccine 2016; 34:4712–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Holbrook BC, Kim JR, Blevins LK, Jorgensen MJ, Kock ND, D'Agostino RB Jr et al A novel R848‐conjugated inactivated influenza virus vaccine is efficacious and safe in a neonate nonhuman primate model. J Immunol 2016; 197:555–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim JR, Holbrook BC, Hayward SL, Blevins LK, Jorgensen MJ, Kock ND et al Inclusion of flagellin during vaccination against influenza enhances recall responses in nonhuman primate neonates. J Virol 2015; 89:7291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dowling DJ, van Haren SD, Scheid A, Bergelson I, Kim D, Mancuso CJ et al TLR7/8 adjuvant overcomes newborn hyporesponsiveness to pneumococcal conjugate vaccine at birth. JCI Insight 2017; 2:e91020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll‐like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol 2004; 5:987–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll‐like receptors: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Microbes Infect 2004; 6:1382–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Willems F, Vollstedt S, Suter M. Phenotype and function of neonatal DC. Eur J Immunol 2009; 39:26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goriely S, Vincart B, Stordeur P, Vekemans J, Willems F, Goldman M et al Deficient IL‐12(p35) gene expression by dendritic cells derived from neonatal monocytes. J Immunol 2001; 166:2141–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Langrish CL, Buddle JC, Thrasher AJ, Goldblatt D. Neonatal dendritic cells are intrinsically biased against Th‐1 immune responses. Clin Exp Immunol 2002; 128:118–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zaghouani H, Hoeman CM, Adkins B. Neonatal immunity: faulty T‐helpers and the shortcomings of dendritic cells. Trends Immunol 2009; 30:585–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. De Wit D, Tonon S, Olislagers V, Goriely S, Boutriaux M, Goldman M et al Impaired responses to toll‐like receptor 4 and toll‐like receptor 3 ligands in human cord blood. J Autoimmun 2003; 21:277–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Krumbiegel D, Zepp F, Meyer CU. Combined Toll‐like receptor agonists synergistically increase production of inflammatory cytokines in human neonatal dendritic cells. Hum Immunol 2007; 68:813–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, Mortha A. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu Rev Immunol 2013; 31:563–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ma R, Du JL, Huang J, Wu CY. Additive effects of CpG ODN and R‐848 as adjuvants on augmenting immune responses to HBsAg vaccination. Biochem Biophys Res Comm 2007; 361:537–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wille‐Reece U, Flynn BJ, Lore K, Koup RA, Kedl RM, Mattapallil JJ et al HIV Gag protein conjugated to a Toll‐like receptor 7/8 agonist improves the magnitude and quality of Th1 and CD8+ T cell responses in nonhuman primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102:15190–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tomai MA, Miller RL, Lipson KE, Kieper WC, Zarraga IE, Vasilakos JP. Resiquimod and other immune response modifiers as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2007; 6:835–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vasilakos JP, Tomai MA. The use of Toll‐like receptor 7/8 agonists as vaccine adjuvants. Expert Rev Vaccines 2013; 12:809–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Caron G, Duluc D, Fremaux I, Jeannin P, David C, Gascan H et al Direct stimulation of human T cells via TLR5 and TLR7/8: flagellin and R‐848 up‐regulate proliferation and IFN‐γ production by memory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol 2005; 175:1551–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hammond T, Lee S, Watson MW, Flexman JP, Cheng W, Fernandez S et al Toll‐like receptor (TLR) expression on CD4+ and CD8+ T‐cells in patients chronically infected with hepatitis C virus. Cell Immunol 2010; 264:150–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kabelitz D. Expression and function of Toll‐like receptors in T lymphocytes. Curr Opin Immunol 2007; 19:39–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bekeredjian‐Ding IB, Wagner M, Hornung V, Giese T, Schnurr M, Endres S et al Plasmacytoid dendritic cells control TLR7 sensitivity of naive B cells via type I IFN. J Immunol 2005; 174:4043–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bourke E, Bosisio D, Golay J, Polentarutti N, Mantovani A. The toll‐like receptor repertoire of human B lymphocytes: inducible and selective expression of TLR9 and TLR10 in normal and transformed cells. Blood 2003; 102:956–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hanten JA, Vasilakos JP, Riter CL, Neys L, Lipson KE, Alkan SS et al Comparison of human B cell activation by TLR7 and TLR9 agonists. BMC Immunol 2008; 9:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bekeredjian‐Ding I, Jego G. Toll‐like receptors – sentries in the B‐cell response. Immunology 2009; 128:311–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pettengill MA, van Haren SD, Li N, Dowling DJ, Bergelson I, Jans J et al Distinct TLR‐mediated cytokine production and immunoglobulin secretion in human newborn naive B cells. Innate Immun 2016; 22:433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xu S, Koldovsky U, Xu M, Wang D, Fitzpatrick E, Son G et al High‐avidity antitumor T‐cell generation by toll receptor 8‐primed, myeloid‐derived dendritic cells is mediated by IL‐12 production. Surgery 2006; 140:170–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simone R, Floriani A, Saverino D. Stimulation of human CD4 T lymphocytes via TLR3, TLR5 and TLR7/8 up‐regulates expression of costimulatory and modulates proliferation. Open Microbiol J 2009; 3:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Peng G, Guo Z, Kiniwa Y, Voo KS, Peng W, Fu T et al Toll‐like receptor 8‐mediated reversal of CD4+ regulatory T cell function. Science 2005; 309:1380–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Levy O, Suter EE, Miller RL, Wessels MR. Unique efficacy of Toll‐like receptor 8 agonists in activating human neonatal antigen‐presenting cells. Blood 2006; 108:1284–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mizel SB, Bates JT. Flagellin as an adjuvant: cellular mechanisms and potential. J Immunol 2010; 185:5677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tarahomjoo S. Utilizing bacterial flagellins against infectious diseases and cancers. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014; 105:275–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Means TK, Hayashi F, Smith KD, Aderem A, Luster AD. The Toll‐like receptor 5 stimulus bacterial flagellin induces maturation and chemokine production in human dendritic cells. J Immunol 2003; 170:5165–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCarron M, Reen DJ. Activated human neonatal CD8+ T cells are subject to immunomodulation by direct TLR2 or TLR5 stimulation. J Immunol 2009; 182:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bates JT, Honko AN, Graff AH, Kock ND, Mizel SB. Mucosal adjuvant activity of flagellin in aged mice. Mech Ageing Dev 2008; 129:271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bates JT, Uematsu S, Akira S, Mizel SB. Direct stimulation of tlr5+/+ CD11c+ cells is necessary for the adjuvant activity of flagellin. J Immunol 2009; 182:7539–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Honko AN, Mizel SB. Mucosal administration of flagellin induces innate immunity in the mouse lung. Infect Immun 2004; 72:6676–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J Immunol 2001; 167:1882–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fujita Y, Taguchi H. Overview and outlook of Toll‐like receptor ligand‐antigen conjugate vaccines. Ther Deliv 2012; 3:749–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McDermott PF, Ciacci‐Woolwine F, Snipes JA, Mizel SB. High‐affinity interaction between Gram‐negative flagellin and a cell surface polypeptide results in human monocyte activation. Infect Immun 2000; 68:5525–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pozzi LA, Maciaszek JW, Rock KL. Both dendritic cells and macrophages can stimulate naive CD8 T cells in vivo to proliferate, develop effector function, and differentiate into memory cells. J Immunol 2005; 175:2071–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Curtsinger JM, Valenzuela JO, Agarwal P, Lins D, Mescher MF. Cutting edge: type IIFNs provide a third signal to CD8 T cells to stimulate clonal expansion and differentiation. J Immunol 2005; 174:4465–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Perez VL, Lederer JA, Lichtman AH, Abbas AK. Stability of Th1 and Th2 populations. Int Immunol 1995; 7:869–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lynn GM, Laga R, Darrah PA, Ishizuka AS, Balaci AJ, Dulcey AE et al In vivo characterization of the physicochemical properties of polymer‐linked TLR agonists that enhance vaccine immunogenicity. Nat Biotechnol 2015; 33:1201–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tomura M, Hata A, Matsuoka S, Shand FH, Nakanishi Y, Ikebuchi R et al Tracking and quantification of dendritic cell migration and antigen trafficking between the skin and lymph nodes. Sci Rep 2014; 4:6030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Langlet C, Tamoutounour S, Henri S, Luche H, Ardouin L, Gregoire C et al CD64 expression distinguishes monocyte‐derived and conventional dendritic cells and reveals their distinct role during intramuscular immunization. J Immunol 2012; 188:1751–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Allan RS, Waithman J, Bedoui S, Jones CM, Villadangos JA, Zhan Y et al Migratory dendritic cells transfer antigen to a lymph node‐resident dendritic cell population for efficient CTL priming. Immunity 2006; 25:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vono M, Lin A, Norrby‐Teglund A, Koup RA, Liang F, Lore K. Neutrophils acquire antigen presentation capacity to memory CD4+ T cells in vitro and ex vivo . Blood 2017; 129:1991–2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Siegrist CA, Aspinall R. B‐cell responses to vaccination at the extremes of age. Nat Rev Immunol 2009; 9:185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kaur K, Chowdhury S, Greenspan NS, Schreiber JR. Decreased expression of tumor necrosis factor family receptors involved in humoral immune responses in preterm neonates. Blood 2007; 110:2948–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Timens W, Rozeboom T, Poppema S. Fetal and neonatal development of human spleen: an immunohistological study. Immunology 1987; 60:603–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tasker L, Marshall‐Clarke S. Functional responses of human neonatal B lymphocytes to antigen receptor cross‐linking and CpG DNA. Clin Exp Immunol 2003; 134:409–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Browne EP. Toll‐like receptor 7 controls the anti‐retroviral germinal center response. PLoS Pathog 2011; 7:e1002293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Clingan JM, Matloubian M. B cell‐intrinsic TLR7 signaling is required for optimal B cell responses during chronic viral infection. J Immunol 2013; 191:810–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kasturi SP, Skountzou I, Albrecht RA, Koutsonanos D, Hua T, Nakaya HI et al Programming the magnitude and persistence of antibody responses with innate immunity. Nature 2011; 470:543–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Onodera T, Hosono A, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Kaminogawa S, Okuno Y et al Whole‐virion influenza vaccine recalls an early burst of high‐affinity memory B cell response through TLR signaling. J Immunol 2016; 196:4172–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dorner M, Brandt S, Tinguely M, Zucol F, Bourquin JP, Zauner L et al Plasma cell Toll‐like receptor (TLR) expression differs from that of B cells, and plasma cell TLR triggering enhances immunoglobulin production. Immunology 2009; 128:573–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gururajan M, Jacob J, Pulendran B. Toll‐like receptor expression and responsiveness of distinct murine splenic and mucosal B‐cell subsets. PLoS One 2007; 2:e863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdickova N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL et al CD69 acts downstream of interferon‐α/β to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature 2006; 440:540–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. m229 does not have stimulatory activity.

Figure S2. There are no significant differences in the number of CD11c+ or CD14+ CD11b+ cells in the draining axillary lymph nodes of the PBS control arm of the vaccinated compared to non‐vaccinated (PBS) animals.

Figure S3. The number of total or activated T or B cells in the draining axillary lymph nodes of the PBS control arm of the vaccinated newborns is not significantly different from the number in the animals that did not receive vaccine (PBS).