Abstract

Background

Granular cell tumors are benign lesions that typically occur in the oral cavity, but can also be found in other sites. However, the characteristics of these tumors are unclear. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the immunohistological characteristics of these tumors of the tongue.

Methods

Seven patients were treated for granular cell tumors of the tongue at our institution during 2003–2017. Paraffin-embedded specimens were available for all cases; thus, retrospective immunohistochemical analyses were performed.

Results

All cases exhibited cytoplasmic acidophilic granules in the muscle layer of the tumor. Both the normal nerve cells and tumor cells also stained positive for PGP9.5, NSE, calretinin, and GFAP. A nucleus of tumor cells was typically present in the margin. The PAS-positive granules were also positive for CD68 (a lysozyme glycoprotein marker). Various sizes of nerve fibers were observed in each tumor, and granular cells were observed in the nerve fibers of a representative case.

Conclusions

Based on our immunohistological findings, granular cell tumors may be derived from Schwann cells, and the presence of CD68 indicates that Wallerian degeneration after nerve injury may be a contributor to tumor formation. Thus, a safe surgical margin is needed to detect the infiltrative growth of granular cell tumors.

Keywords: Granular cell tumor, Oral cavity, Immunohistochemistry, Wallerian degeneration

Background

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) are rare, benign tumors that were first reported as granular cell myoblastomas in 1926 [1]. The term GCT was first introduced in the 2005 version of the World Health Organization’s Classification of Tumors [2]. Contrary to the belief that GCTs have a myogenic origin, an immunohistochemical study [3] has revealed that GCTs are of neural origin, with diffuse expression of S-100 protein present in almost every case. However, there is no clear consensus regarding the mechanism of GCT development. GCTs display cytoplasmic acidophilic granule-like structures, and exhibit many polygonal neoplastic cells that multiply in an alveolar configuration. Because GCTs lack a capsule, they have poorly differentiated margins and frequently exhibit recurrence [4, 5]. Thus, curative treatment for GCTs requires a sufficient clear surgical margin. GCTs are frequently detected in soft tissues throughout the body, especially the skin and oral cavity [5], although the origin of this tumor remains unclear. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the immunohistological characteristics of oral GCTs of the tongue.

Methods

Case selection

We retrospectively reviewed records from cases of oral GCTs of the tongue, treated in our hospital during a 15-year period (2003–2017), and identified 7 cases that had been treated by resection. The specimen submission forms were used to extract the data on patient’s age and sex, and the location of the lesion. Paraffin-embedded specimens were available for all cases, which allowed us to perform detailed histopathological and immunohistochemical analyses. All patients had provided informed consent for treatment, and this study’s retrospective design was approved by our Institutional Review Board (reference number: 150,033).

Morphological assessment

Slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin to evaluate the following morphological parameters: surgical margin status, presence of pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia and cytoplasmic acidophilic granules. We also determined the presence of a capsule in these samples.

Immunohistochemical analysis

We stained the slides with antibodies against the following proteins to determine the development mechanism and origin of the GCTs (Table 1):

Table 1.

Characterization of the selected antibodies and their expression in granular cell tumors from various sites

| Marker | Dilution | Supplier | Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-100 protein (rabbit polyclonal antibody) | 1:300 | DakoCytomation | E-F hand family (granule cells, glia cells, Schwann cells) |

| Vimentin (mouse monoclonal antibody) | 1:300 | DakoCytomation | Intermediary filament (granule cells) |

| PGP 9.5 (mouse monoclonal antibody) | 1:300 | DakoCytomation | Nerve cells (cell body, axon, granule cells) |

| NSE (mouse monoclonal antibody) | 1:1000 | DakoCytomation | Nerve cells (axis-cylinder process) |

| Calretinin (rabbit polyclonal antibody) | 1:10 | Spring Biosciences | E-F hand family (Schwann cells, central nerve neurons, mast cells) |

| GFAP (mouse monoclonal antibody) | 1:1000 | Novocastra Laboratories | Glia fiber-related acid protein, Schwann cells |

| CD68 (mouse monoclonal antibody)) | 1:300 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Highly glycosylated membrane proteins, glycoproteins |

| Ki-67 (mouse monoclonal antibody) | 1:400 | DakoCytomation | Proliferation marker |

Abbreviations: NSE neuron-specific enolase, GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein, PGP protein gene product

S-100, a protein from the E-F hand family and a marker widely used in immunostaining of GCTs [5]. The protein was extracted from the brain and is typically found in granule cells, glial cells and Schwann cells.

Vimentin, a protein from the intermediary filament family and associated with the cytoskeleton. It is typically found in granule cells, but has low specificity [5].

The PGP9.5 protein, is seen in nerve cells (cell body and axon) and neuroendocrine cells in the peripheral nervous system. This protein is extracted from the brain, and GCTs exhibit a broad range of staining intensities for PGP9.5 [5, 6].

The NSE protein is a marker of nerve cells (axis cylinder process) and neuroendocrine cells in the peripheral nervous system. This protein is highly specific for nerve cells (axis cylinder process) in all organs, and is produced in large quantities by neuroendocrine cell-derived tumors. Thus, NSE has been used for the diagnosis and monitoring of small-cell lung cancer, neuroblastoma, and neuroendocrine tumors [7].

The calretinin protein, an E-F hand family protein produced in the central nervous system (similar to S-100) [5]. Calretinin is typically found in Schwann cells, neurons of the central nervous system and mast cells.

The GFAP protein is associated with glial fiber-related acid protein and Schwann cells, and is an intermediate filament protein, specific to astroglial cells [8]. The expression of GFAP increases in cases of cerebral damage, dementia, prion disease, and neurologic diseases such as multiple sclerosis.

The CD68 protein is associated with highly glycosylated membrane proteins, glycoproteins, and mucin-like membrane proteins of lysozymes [9]. This protein is typically found in macrophages, fibroblasts, and Schwann cells.

The Ki-67 protein, a cell proliferation marker used to examine the proliferation status of tumor cells [10].

Results

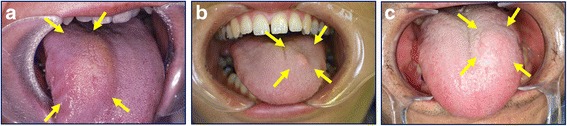

All 7 GCTs occurred in the tongues of middle-aged or elderly patients, all of whom had presented with a hard lump in their tongue (Table 2, Fig. 1). The tumor dimensions ranged from 5 to 29 mm. In all cases, the clinical diagnosis was fibroma. No cases of recurrence were observed over a maximum follow-up period of 15 years.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Major complaint | Location | Size (mm) | Mucosal color | Lingual trauma from occlusion | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | F | Hard lump | Tongue | 8 × 8 | Normal | + | 202 |

| 2 | 43 | F | Hard lump | Tongue | 20 × 29 | Normal | + | 177 |

| 3 | 53 | F | Hard lump | Tongue | 7 × 7 | Normal | – | 162 |

| 4 | 39 | M | Hard lump | Tongue | 5 × 5 | Normal | – | 147 |

| 5 | 35 | F | Hard lump | Tongue | 7 × 7 | Normal | – | 108 |

| 6 | 62 | M | Hard lump | Tongue | 16 × 17 | Normal | + | 65 |

| 7 | 70 | F | Hard lump | Tongue | 13 × 18 | Normal | – | 40 |

Abbreviations: F female, M male

Fig. 1.

Granular cell tumors of the tongue (arrows). a Case 2, b Case 5, and c Case 6

All cases exhibited cytoplasmic acidophilic granules in the tumor muscle layer. A nucleus of tumor cells was typically present in the marginal regions. In none of the cases the lesion was covered by a capsule and only 3 cases exhibited pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia. All surgical margins were >10 mm.

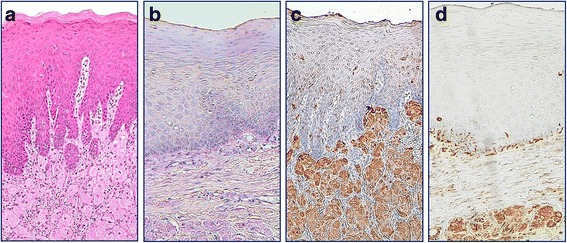

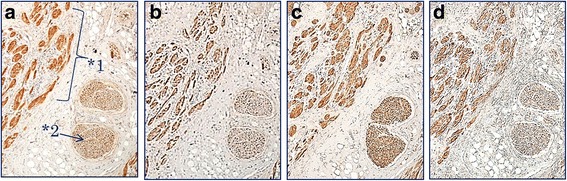

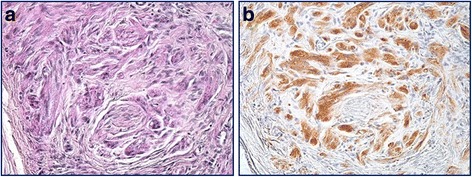

Immunohistochemical findings are summarized in Table 3. All cases stained positively for PAS, S-100 protein, vimentin, PGP 9.5, NSE, calretinin, GFAP, and CD68 (Figs. 2 and 3). Co-expression of PGP 9.5, NSE, calretinin, and GFAP in the tumor cells and normal nerve cells was observed in all cases (Fig. 3). The PAS-positive granules were also positive for the lysozyme glycoprotein marker, CD68 (Fig. 4). Nerve fibers of various sizes were observed in each tumor and granular cells were observed in the nerve fibers from a representative case (Case 2; Fig. 5). The tumors exhibited sporadic staining for Ki-67, with a mean Ki-67 index of 1.89% (low cell proliferation index; Table 3).

Table 3.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical characteristics in 7 cases of GCT of the tongue

| Case | Capsule | PCH | S-100 protein | Vimentin | PGP 9.5 | NSE | Calretinin | GFAP | CD68 | PAS | Ki-67 index (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 2.57 |

| 2 | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 3.22 |

| 3 | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1.21 |

| 4 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 0.42 |

| 5 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1.83 |

| 6 | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1.63 |

| 7 | – | – | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 2.42 |

Abbreviations GCT granular cell tumors, GFAP glial fibrillary acidic protein, NSE neuron-specific enolase, PAS periodic acid-Schiff, PCH pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia, PGP protein gene product

aThe Ki-67 index was calculated as the percentage of positive cells in a minimum sample of 1000 cells. Mean Ki-67 index, 1.89%

Fig. 2.

a Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia associated with granular cell tumors (hematoxylin and eosin staining). All cases stained positive for b periodic acid-Schiff, c S-100 protein, and d vimentin (magnification, 100×)

Fig. 3.

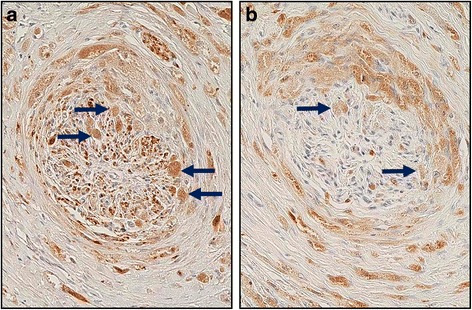

Immunohistochemistry revealed that the tumor cells (*1) and normal nerve cells (*2) expressed a protein gene product 9.5, b neuron-specific enolase, c calretinin, and d glial fibrillary acidic protein (magnification, 40×)

Fig. 4.

Granules stained positive for a periodic acid-Schiff and b the lysozyme glycoprotein marker, CD68 (magnification, 200×)

Fig. 5.

Granular cells (arrows) were observed in a nerve fiber from a representative case that was stained for a protein gene product 9.5 and b CD68 (magnification, 200×)

Discussion

GCTs are relatively rare benign tumors that can occur throughout the body. The tongue is involved in ≥60% of oral GCTs, although these tumors can also be found in the head and neck region, buccal mucosa, hard palate, lips and gingiva [3]. A previous study [11] indicated that women are more likely to develop GCTs than men and we observed similar distribution. It is difficult to confirm a clinical diagnosis of GCT, since these tumors do not have clear clinical characteristics. The first treatment of choice is surgical resection. Since the tumor does not have a capsule and presents with undefined borders, careful resection with clear margins is essential to avoid recurrence [11], an event observed in approximately 20% of cases because of the presence of a resected stump [12]. Although malignant changes (histologic evidence of vesicular nucleus with a prominent nucleolus, high mitotic activity, high nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio and pleomorphism) are relatively rare, and seen in 1–2% of cases [13, 14], prevention of a malignant transformation may also aid in preventing recurrence. Thus, a broad surgical margin is needed to prevent recurrence. In the present study, the tumors had relatively small volumes, and a 10-mm margin, based on palpation of the tumor mass, was considered sufficient. It is unclear whether a 10-mm margin can be used for all GCTs, although a 10-mm margin from the palpated mass may be appropriate in cases of GCT with small sizes.

Several theories have been proposed regarding the origin of GCTs. In 1926 Abrikosoff described this tumor as a “granular cell myoblastoma”, because of the presence of striated muscle blast cells. However, different reports [15–18] have suggested different origins, such as myogenic, neurogenic, histiocytic and fibroblastic. Nevertheless, based on the presence of the highly specific S-100 protein, it is highly likely that Schwann cells are involved, which was first described in 1982, alongside glial cells [11], resulting in a name change for these tumors to GCT in the 2005 version of the World Health Organization’s Classification of Tumors [2].

In the present study, all cases exhibited PAS-positive granules in the tumor cells alongside positive staining for S-100 protein and vimentin (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the tumor cells and normal nerve cells exhibited co-expression of nerve markers PGP 9.5, NSE, calretinin, and GFAP (Fig. 3), suggesting that the nervous system plays a role in the development of this tumor. Besides, varying thicknesses of funiculi were present in all of the tumors and Schwann cells exhibited findings that were comparable to those of granule cells (Fig. 5). These findings suggest that GCTs may originate from Schwann cells.

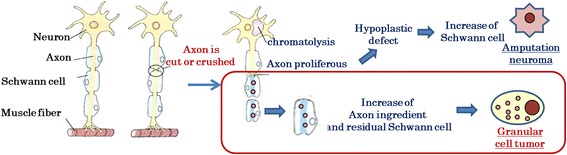

The cytoplasmic granular structures of the tumor cells are lysozymes, as they show positive staining for CD68 (Fig. 4), and are reported to contain glycogen, a myelin-like structure, and a phospholipid membrane [19]. As such, neurodegenerative injury has been suggested to be involved in the development and reproduction of GCT cells [20]. In our study, lingual trauma from occlusion was observed in 3 cases, leading to a conclusion that the development of GCT may involve Wallerian degeneration after axonal injury, which generates an axon fragment (i.e., glycogen and the myelin-like structure) with Schwann cells. This fragment may lead to a malignant transformation that can result in cancerous growth and the development of GCT (Fig. 6). An amputation neuroma may also be another cause. Though there are few reports of GCT occurring in such a situation, it is extremely unlikely that both will occur simultaneously. Hence, GCTs can arise in all soft tissues that might experience mechanical stimulation. It should be kept in mind that various other factors, besides Wallerian degeneration, may influence the developmental process in locations not exposed to mechanical injury (e.g., the lungs) [12].

Fig. 6.

Regeneration of damaged axons may cause Wallerian degeneration. This process is induced after a nerve fiber is mechanically cut or crushed and results in distal degeneration of the axon after it is separated from the neuronal cell body. The axon fragment and residual Schwann cells may participate in the development of a granular cell tumor. Therefore, Wallerian degeneration may play an important role in the development of granular cell tumors

All 7 cases exhibited a low Ki-67 index, which explained the favorable prognoses in our patients, with no signs of recurrence seen after a follow-up period of 15 years. Previous studies had revealed that a Ki-67 index of >10% was associated with local GCT recurrence [10].

Conclusions

Our immunohistological findings suggest that GCTs are derived from Schwann cells. Furthermore, the CD68-positive findings indicate that Wallerian degeneration may also contribute to nerve injury. A safe surgical margin is needed to identify infiltrative growth of GCTs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

For confidentiality issues, the data will only be shared in aggregate form as presented in the tables and figures in the manuscript.

Author’s contributions

AM made the initial diagnosis, prepared the first draft of the manuscript and took the required photos. AM, MO and SY planned the treatment. AM and SY analyzed the collected data and contributed to the final drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- GCT

Granular cell tumors

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- NSE

Nerves-specific enolase

- PAS

Periodic acid Schiff

- PGP

Protein gene product

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients had provided informed consent for treatment, and this study’s retrospective design was approved by our Institutional Review Board (reference number 150033).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients for publication of this article and any accompanying images.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abrikossoff A. Ueber Myome, ausgehend von der quergestreifen willkurlichen. Muskulatur. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat. 1926;260:215–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02078314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speight P. Granular cell tumor. In: Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, editors. World Health Organization classification of Tumours. Pathology and genetics. Head and neck tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005. pp. 185–186. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart CM, Watson RE, Eversole LR, Fischlschweiger W, Leider AS. Oral granular cell tumors: a clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:427–435. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90357-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meissner M, Wolter M, Schöfer H, Kaufmann R. A solid erythematous tumour. Granular cell tumour (GCT) Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:e44–e45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2009.03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vered M, Carpenter WM, Buchner A. Granular cell tumor of the oral cavity: updated immunohistochemical profile. J Oral Pathol Med. 2009;38:150–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahalingam M, Lo-Piccolo D, Byers HR. Expression of PGP 9.5 in granular sheath tumors: an immunohistochemical study of six cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:282–286. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028006282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fendler WP, Wenter V, Thornton HI, Ilhan H, von Schweinitz D, Coppenrath E, et al. Combined Scintigraphy and tumor marker analysis predicts unfavorable histopathology of Neuroblastic tumors with high accuracy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0132809. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nielsen AL, Holm IE, Johansen M, Bonven B, Jørgensen P, Jørgensen AL. A new splice variant of glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP epsilon, interacts with the presenilin proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29983–29991. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112121200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kunisch E, Fuhrmann R, Roth A, Winter R, Lungerhausen W, Kinne RW. Macrophage specificity of three anti-CD68 monoclonal antibodies (KP1, EBM11, and PGM1) widely used for immunohistochemistry and flow cytometry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:774–784. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.013029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fanburg-Smith JC, Meis-Kindblom JM, Fante R, Kindblom LG. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:779–794. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuchida T, Okada K, Itoi E, Sato T, Sato K. Intramuscular malignant granular cell tumor. Skelet Radiol. 1997;26:116–121. doi: 10.1007/s002560050204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, Crawford BE, Klappenbach S, Rowden G, et al. Granular cell tumor: a clinicopathologic study of 110 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1980;13:301–316. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930130405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Budiño-Carbonero S, Navarro-Vergara P, Rodríguez-Ruiz JA, Modelo-Sánchez A, Torres-Garzón L, Rendón-Infante JI, et al. Granular cell tumors: review of the parameters determining possible malignancy. Med Oral. 2003;8:294–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torrijos-Aguilar A, Alegre-de Miquel V, Pitarch-Bort G, Mercader-García P, Fortea-Baixauli JM. Cutaneous granular cell tumor: a clinical and pathologic analysis of 34 cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2009;100:126–132. doi: 10.1016/S0001-7310(09)70230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murray MR. Cultural characteristics of three granular-cell myoblastomas. Cancer. 1951;4:857–865. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195107)4:4<857::AID-CNCR2820040423>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fisher ER, Wechsler H. Granular cell myoblastoma--a misnomer. Electron microscopic and histochemical evidence concerning its Schwann cell derivation and nature (granular cell schwannoma) Cancer. 1962;15:936–954. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196209/10)15:5<936::AID-CNCR2820150509>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azzopardi JG. Histogenesis of granular-cell myoblastoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1956;71:85–94. doi: 10.1002/path.1700710113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pearse AG. The histogenesis of granular-cell myoblastoma (? Granular-cell perineural fibroblastoma) J Pathol Bacteriol. 1950;62:351–362. doi: 10.1002/path.1700620306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobel HJ, Marquet E, Schwarz R. Is schwannoma related to granular cell myoblastoma? Arch Pathol. 1973;95:396–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coleman MP, Freeman MR. Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:245–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

For confidentiality issues, the data will only be shared in aggregate form as presented in the tables and figures in the manuscript.