Abstract

The Eu3+/2+ redox couple provides a convenient design platform for responsive pO2 sensors for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Specifically the Eu2+ ion provides T1w contrast enhancement under hypoxic conditions in tissues, whereas, under normoxia, the Eu3+ ion can produce contrast from chemical exchange saturation transfer in MRI. The oxidative stability of the Eu3+/2+ redox couple for a series of tetraaza macrocyclic complexes was investigated in this work using cyclic voltammetry. A series of Eu-containing cyclen-based macrocyclic complexes revealed positive shifts in the Eu3+/2+ redox potentials with each replacement of a carboxylate coordinating arm of the ligand scaffold with glycinamide pendant arms. The data obtained reveal that the complex containing four glycinamide coordinating pendant arms has the highest oxidative stability of the series investigated.

Keywords: Divalent lanthanide, cyclic voltammetry lanthanides, hypoxia imaging agents, Redox chemistry of lanthanides

Graphical Abstract

The redox stability of Eu3+/Eu2+ couple shifts more positive and closer to the aqua ion for complexes with softer donor atoms (amide oxygen) compared to harder donor atoms (carboxylate).

Introduction

The paramagnetic properties of trivalent lanthanide complexes have been applied in a variety of biomedical imaging applications. The most widely known clinical application is the use of Gd3+-based complexes (4f7, S = 7/2) as T1-shortening contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging.[1] Interest in other trivalent lanthanide ions as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been growing since the introduction of lanthanide-based paramagnetic chemical exchange saturation transfer (paraCEST) as a mechanism for altering image contrast.[2] Until recently, most complexes for biomedical applications have used lanthanide ions in the most stable, trivalent oxidation state. However, the divalent oxidation state has been reported for all the lanthanides (except Pm) and is relatively common for a few lanthanides (Eu2+, Sm2+, and Yb2+), but these divalent ions are unstable in oxygenated solutions.[3] Among the divalent lanthanide ions, the Eu2+ ion is of particular interest in MRI applications because it is isoelectronic (4f7, S = 7/2) with Gd3+ and, consequently, has a similar relaxation effect on water protons.[4] Additionally, Eu2+ is the most stable divalent lanthanide with respect to oxidation, thereby enabling its study in aqueous media. Consequently, a number of investigations have focused on ligand designs that further stabilize the +2 oxidation state of the europium ion,[4a, 5] and these studies often invoke hard–soft acid–base theory because Eu2+ (~117 pm) is considered a softer metal ion than Eu3+ (~103 pm).[6]

An attractive feature of europium complexes as contrast agents for MRI is that the contrast enhancement generated by these complexes depends on the oxidation state of the metal ion. Specifically, Eu2+-containing complexes are efficient T1w-relaxation agents that can be converted, upon oxidation, into paraCEST agents, provided the Eu3+-containing complex resulting from oxidation of Eu2+ has exchangeable protons or bound water characteristics favorable for CEST.[7] The ligand coordinating the Eu3+/2+ ion plays an important role in tuning these exchange characteristic that are critical for imaging in addition to influencing the oxidative stability of Eu2+. Cryptand-type ligands stabilize the Eu2+-oxidation state and enable fast water exchange for efficient shortening of the bulk water T1. This ligand system permits the differentiation of oxygen-poor from oxygen-rich environments in vivo,[8] including distinguishing necrotic from non-necrotic tumor tissue.[9] However, with rapidly exchanging coordinated water and no exchangeable protons on the macrocylic ligand, discrete cryptates of europium, outside of liposomes,[10] are not good at influencing CEST compared to europium complexes that contain exchangeable protons.

We recently demonstrated that Eu(3) (Chart 1) shortens T1 in the reduced state (Eu2+) and produces a CEST signal in the oxidized state (Eu3+).[7] When the agent was injected directly into muscle tissue of healthy mice, both contrast modalities were observable: the T1 effect lasted for about 20 minutes before completely diminishing, and after 15 minutes, it was possible to detect the CEST effect.[7b] Furthermore, Eu2+(3) displays kinetic selectivity for small molecule oxidizing agents that prevents other biologically relevant oxidizing agents, such as glutathione disulfide, from oxidizing Eu2+(3) to Eu3+(3) on imaging-relevant timescales.[11]

Chart 1.

Cyclen-based ligands examined in this work.

Accordingly, there is growing precedent for the use of Eu3+/2+-cyclen-based-(tetraamide) derivatives as oxygen-sensitive MRI contrast agents in which one form of contrast (T1w, +2 oxidation state of Eu) is turned off in response to O2, while the other form (paraCEST, +3 oxidation state of Eu) is turned on simultaneously. This dual contrast feature makes the Eu3+/2+ redox couple promising in the design of responsive O2 sensors for MRI. Cyclic voltammetry has been traditionally used to evaluate the oxidative stability of Eu2+-containing complexes.[4a,5] The Eu3+/2+-redox couple in water has been reported to be chemically reversible or quasi-reversible depending upon the electrochemical parameters.[5a, 12] The redox potential of the Eu3+/2+ redox couple plays an important role in the design of Eu3+/2+-based redox-responsive probes. Ideally, the Eu3+/2+ redox couple should favor the +3 oxidation state in normoxic tissues, and the +2 oxidation state should be stable only in hypoxic tissues.

The redox potentials of the Eu2+ ion in complexes with various ligand systems have been reported including cryptands,[5b] polyoxodiaza cryptands,[13] a Eu-encrypted Preyssler anion,[14] macrocyclic polyaminopolycarboxylates,[4a] polyazacryptands,[6b] and linear polyaminopolycarboxylate-type ligands.[15] With the exception of cryptates and the Eu-encrypted Preyssler anion, the resulting complexes of macrocyclic and linear ligands result in negative redox potentials relative to the Eu3+/2+ aqua ion (−585 mV versus Ag/AgCl).[13] The ability to fine tune the Eu3+/2+-redox couple within a coordination environment suitable for T1 enhancement and paraCEST contrast would be valuable in the rational design of new redox-responsive contrast agents that use the Eu3+/2+-redox switch. Herein, we report the electrochemical behavior of a series of cyclen-based europium complexes with variable numbers of glycinamide and acetate pendant arms (Chart 1). The redox stability of these complexes was investigated using cyclic voltammetry, and the influence of carboxylate versus amide coordination on the oxidative stability of Eu2+ is discussed.

Results and Discussion

The redox potential of a metal ion can be strongly influenced by coordination environment. This phenomenon is well-studied in bioinorganic, catalysis, and basic coordination chemistry.[16] Given the broad interest in redox-responsive contrast agents,[17] we set out to compare the oxidative stability of the europium complexes of DOTA-glycinate congeners (DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) with a stepwise increase in the number of glycinamide pendant arms relative to acetate pendant arms on the DOTA scaffold (Chart 1). DOTA, 1, 3, (N-chloroacetyl) glycine tert-butyl ester and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,7-bis(acetic acid tert-butyl ester) (intermediate A) were synthesized as previously described.[18] Ligand 2 was synthesized using a two-step process (Scheme 1). The first step involved the reaction of two equivalents of (N-chloroacetyl) glycine tert-butyl ester with one equivalent of intermediate A. Acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of the tert-butyl esters yielded 2. The corresponding europium complexes were prepared by reacting ligands 1–3 or DOTA with EuCl3 in water at pH 6.5. With a series of europium-containing complexes with varying numbers of glycinamide and acetate pendant arms, we turned our attention to studying the complexes in solution.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route to ligand 2.

1H-NMR spectroscopy was used to investigate the coordination geometry of Eu3+ complexes of ligands 1–3 in solution. Typically, Eu3+-complexes of DOTA-tetraamide ligand systems adopt two coordination geometries in solution, which are distinguishable by high-resolution 1H-NMR spectroscopy.[2, 19] Accordingly, we acquired 1H-NMR spectra of the Eu3+ complexes Eu(1) and Eu(2) (D2O, 9.4 T, and 25 °C, Figures S1 and S2). Ligand 2 has C2 symmetry; therefore, Eu(2) is expected to have a relatively simplified 1H-NMR spectrum compared to Eu(1) because ligand (1) has only C1 symmetry. The number of resonances of the europium complexes is consistent with the expected symmetry for these chelates. In these spectra either four or two highly downfield shifted resonances are observed: 31.89, 30.80, 29.72, and 29.53 ppm for Eu(1) and 29.98 and 28.54 ppm for Eu(2). The observed chemical shift around 30 ppm is characteristic for the axial macrocyclic H4 protons of the square anti-prismatic (SAP) isomer,[19] suggesting that trivalent Eu(1) and Eu(2) predominantly exist as the SAP isomers in solution. The NMR spectra of Eu-DOTA and Eu(3) were consistent with previous reports and also indicated that the complexes are predominantly the SAP isomer in solution.[18b, 20]

To characterize the effect of varying numbers of glycinamide and acetate pendant arms on the Eu3+/2+ redox couple, we acquired cyclic voltammograms (Figure 1) using a standard three-electrode setup consisting of a gold working electrode, platinum auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode with KCl (1 M) as a supporting electrolyte at pH 7.0. A gold working electrode was chosen for a large cathodic window (−200 to −1500 mV) and EuCl3 (aq) was used to compare our values with reported values of the Eu3+/2+ redox couple. Diffusion control studies for all complexes were also performed (Figures S3–S10). Table 1 provides an overview of the electrochemical data collected for EuCl3 and complexes Eu(1), Eu(2), and Eu(3) at different scan rates. Plots of the Ipc and Ipa versus the square root of the scan rate (v1/2) (Figures S6, S8, and S10) indicate that the Eu3+/2+ couple in complexes Eu(1)–Eu(3) is diffusion controlled and quasi-reversible under the conditions used in the electrochemistry experiments.

Figure 1.

Cyclic voltammograms of Eu(3) (green), Eu(2) (black), Eu(1) (blue), and Eu-DOTA (purple) at pH 7.0 measured at a scan rate of 100 mV/s. Inset: Potential region containing the Eu3+/2+ redox couple for all complexes investigated.

Table 1.

Electrochemical data collected on samples (20 mM) of EuCl3, Eu(1), Eu(2), and Eu(3) in aqueous solution, pH 7.0, using a gold working electrode, platinum auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode at different scan rates.

| Scan Rate (mV/s) | EuCl3 | Eu(1) | Eu(2) | Eu(3) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1/2 (mV) | δE (mV) | Ipa/Ipc | E1/2 (mV) | δE (mV) | Ipa/Ipc | E1/2 (mV) | δE (mV) | Ipa/Ipc | E1/2 (mV) | δE (mV) | Ipa/Ipc | |

| 100 | −636.5 | 89 | 0.9 | −1110.5 | 105 | 1.6 | −1068.0 | 70 | 1.3 | −971.0 | 78 | 0.7 |

| 300 | −637.5 | 103 | 0.9 | −1106.5 | 79 | 1.2 | −1065.5 | 69 | 1.1 | −971.0 | 88 | 1.4 |

| 500 | −636.5 | 111 | 0.9 | −1103.5 | 103 | 1.5 | −1069.5 | 73 | 1.0 | −972.5 | 85 | 1.5 |

As a basis of comparison, we measured the redox couple of the Eu3+/2+ aqua ion and observed a redox couple centered at −636.5 mV (versus Ag/AgCl, 100 mV/s). This E1/2 is reasonably close to the reported value (−585 mV versus Ag/AgCl).[13, 21] Additionally, the observed Eu3+/2+ redox event was found to be relatively diffusion controlled as well as chemically reversible through a one-electron transfer (Figures S3 and S4 and Table 1). Ligands change the redox properties of Eu ions, and the redox behavior of Eu-DOTA has been reported using a different working electrode (glassy carbon micro electrode).[21] Therefore, Eu-DOTA was evaluated using the experimental conditions maintained throughout this study to enable comparison with the reported results. Despite overlap of the reduction wave with the aqueous solvent window, an oxidation event was observed at −1101 mV versus Ag/AgCl for Eu-DOTA (Figure S11), similar to the previously reported value of (−1135 mV versus Ag/AgCl).[21]

The cyclic voltammogram of Eu(3), containing four glycinamide pendant arms, revealed a redox couple centered at −971.0 mV versus Ag/AgCl (Table 1). This value is in reasonable agreement with data recently published for this complex (−903 mV versus Ag/AgCl, glassy carbon working electrode, pH 7).[7a] It should be noted that an incorrect E1/2 value of −226 mV versus Ag/AgCl was previously reported for this complex.[7b] The more positive midpoint potential of Eu(3) indicates that the amide-rich coordination environment thermodynamically favors divalent europium relative to Eu- DOTA (Figure 1). However the redox potential measured for Eu-(3) is negatively shifted by 334 mV relative to the aqua ion.

Eu(1) and Eu(2) had midpoint potential of −1110 and −1068 mV, respectively, versus Ag/AgCl (scan rate 100 mV/s, Figures S9 and S7, Table 1). The midpoint potentials of Eu(1) and Eu(2), having both glycinamide and acetate pendant arms, fall between the midpoint potentials of complexes bearing purely acetate, Eu-DOTA, or purely glycinamide, Eu(3), pendant arms. These results indicate that sequential substitution of a negatively charged carboxylate with a neutral amide donor group on a cyclen scaffold increases the oxidative stability of Eu2+. The more positive redox potential of the amide-containing complexes compared with Eu-DOTA likely reflect the increased stability resulting from the interaction between the relatively soft amide oxygen donor atoms with the relatively soft Eu2+ ion.

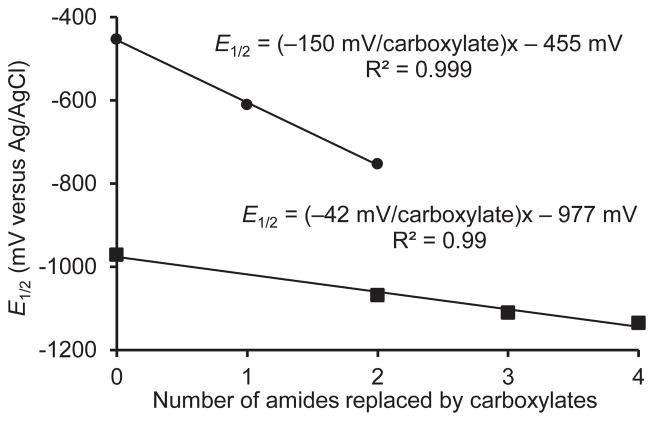

To quantify this observation, we plotted midpoint potentials of Eu(1), Eu(2), Eu(3), and Eu-DOTA as a function of glycinamide pendant arms replaced by acetate pendant arms (Figure 2). From these data, we measured a 42 mV decrease in midpoint potential per glycinamide replaced by acetate, which demonstrates the possibility of fine-tuned control over the Eu3+/2+ redox couple. For comparison, an analogous effect was observed for Eu2+-containing complexes of functionalized 1,10-diaza-18-crown-6 ligands in which negatively charged picolinate sidearms were replaced with neutral picolinamide groups.[13] Interestingly, replacement of the four carboxylates with amides in our macrocyclic complexes shows smaller shifts (~42 mV per substitution) than the picolinate system (~150 mV per substitution) with only two possible positions for pendant arm substitution. This difference is likely due to a variety of structural and electronic differences between the two series of molecules. Regardless of these differences, the overall trends are similar.

Figure 2.

E1/2 versus number of amides replaced by carboxylates on a diaza- 18-crown-6 scaffold with various ratios of picolinamide and picolinate pendant arms (●)[13] and on Eu-DOTA[21] and complexes Eu(1), Eu(2), and Eu(3) presented in this work (■).

Conclusions

In this work, cyclic voltammetry was used to measure the redox potential of the Eu3+/2+ couple in a series of DOTA derivatives with variable number of acetate and glycinamide pendant arms. Ligand 2 and its corresponding Eu3+ complex (Eu(2)) were synthesized and reported for the first time. The shifts observed in the redox potentials for the series of complexes indicate that sequential substitution of amide for carboxylate donor groups in the europium complexes leads to increased oxidative stability of the +2 oxidation state. Among the four complexes studied, europium tetraglycinate complex Eu(3), with four coordinating amide oxygens, was found to have the most positive redox potential and, therefore, the highest oxidative stability. These results emphasize the influence of ligand structure on fine-tuning oxidative stability and might assist in the design of redox-responsive Eu2+-based MR contrast agents.

Experimental Section

General Remarks

All solvents and reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used as received unless otherwise stated. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian VNMRS direct drive Varian console spectrometer operating at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively. Liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LCMS) for ligands and complexes were performed using a Waters analytical HPLC system connected to a Waters QtofMS-XEVO (ESI, positive mode) mass spectrometer. Cyclic voltammograms were obtained in a nitrogen atmosphere at 22 °C using a BASi EC Epsilon potentiostat equipped with a 1.6 mm gold working electrode, a platinum wire auxiliary electrode, and quasi silver/silver chloride reference electrode. Measurements were performed in water (molecular biology reagent grade, Sigma) with KCl (1 M) as the supporting electrolyte.

Synthesis of the ligands

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid (DOTA)[18a] and ligands (1)[22] and (3)[18b] were synthesized following reported procedures.

Synthesis of ligand 2

1,4,7,10-Tetraazacyclododecane-1,7-bis(acetaic acid tert-butyl ester)-4,10-bis(acetic acid glycinamide) (2). This ligand was synthesized by reacting one equivalent of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,7-bis(acetic acid tert-butyl ester) (0.500 g, 1.20 mmol) with 2.1 equivalents of (N-chloroacetyl)glycine tert-butyl ester (519 mg, 2.50 mmol) in the presence of K2CO3 (691 mg, 5.00 mmol) in acetonitrile (20 mL). The hydrolysis of the resulting tert-butyl protected compound (B) with neat trifluroacetic acid (3 mL) followed by evaporation with a stream of N2 gas produced a viscous yellow oil. Precipitation with diethyl ether afforded 682 mg (yield 84%) of the final product as a white powder. 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ = 4.63 (4H, s), 3.79–3.77 (8H, m), 3.41–2.78 (16H, m); 13C NMR (100.6 MHz, D2O) δ 173.07 (C=O), 170.91 (C=O), 163.40 (C=O),55.23 (NCH2C), 54.84 (NHCH2C), 50.69–48.68 (Cyclen), 41.03 (NHCH2CO); MS (ESI positive mode) m/z Found, 519.09; [M + H]+ calculated for C20H35N6O10, 519.24.

Synthesis of Eu3+ complexes

Ligand (1) or (2) was dissolved in water (10 mL), and the pH of the resulting solution was adjusted to 6.5 with NaOH (0.1 M). One equivalent of EuCl3·6H2O was added, and the pH was again adjusted to 6.5 with NaOH (0.1 M) and the resulting solution was stirred at ambient temperature for 24 h. Excess Eu3+ was isolated as Eu(OH)3 by increasing the pH above 8 using aqueous NaOH (1 M) and filtering through a 0.2 μm syringe filter before adjusting the pH to 7 with HCl (1 M). The resulting solution was lyophilized to give the desired complex. The Eu(3) and Eu-DOTA complexes were synthesized using published procedures.[18a, 18b]

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) of Eu(1); δ = 31.89, 30.80 and 29.72, 29.53 (4H, br, ring axS), 3.39 (2H, br, NHCH2CO), 0.32, 0.65, −2.26, −2.57, −3.72, −4.21 (8H, br, NCH2), −6.0, −7.46, −8.32 (4H, br, ring eqC), −10.68, −11.30, −11.51, −12.20, −13.54, −14.25, −15.50, −16.66 (8H, br, ac); MS (ESI positive mode) m/z Found, 612.1135; [M + H]+ calculated for C18H29EuN5O9, 612.1116.

1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) of Eu(2); δ = 29.98, 28.54 (4H, br, ring axS), 5.55, 4.10 (4H, br, NHCH2CO), 0.59, −4.45 (8H, br, NCH2), −6.91, −8.47, (4H, br, ring eqC), −10.13, −12.94, −13.46, −13.81, −17.50 (8H, br, ac); MS (ESI positive mode) m/z Found, 669.1494; [M]+ calculated for C20H32EuN6O10, 669.1403.

Cyclic Voltammetry

A stock solution of pH 7.0 water (molecular biology reagent grade, Sigma) was used for all cyclic voltammetry experiments herein. A solution of KCl (10 mL, 1 M) was prepared with the pH-adjusted water and added to the electrochemical cell. The solution was allowed to stir and sparged with nitrogen for at least 30 minutes prior to each electrochemistry experiment. The three electrodes (gold working electrode, platinum auxiliary electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode) were inserted into the cell setup and a background scan was recorded within a scan window of 0 to −1500 mV, with a scan rate of 100 mV/s, and with three sweeps within this window. A lack of oxygen redox signal verified that oxygen had been removed below detectable levels. The working electrode was removed from the cell, polished, and placed aside. The electrochemical cell was charged with the europium complex in water (3 mL, 20 mM), and the resulting solution was stirred and sparged with nitrogen gas for a period of 15 minutes. The working electrode was placed into the electrochemical cell, and the stirring was stopped before data acquisition. The scan window remained from 0 to −1500 mV, scanned at a rate of 500 mV/s, completing three sweeps within this scan window. The scan window was then adjusted appropriately for the complex of interest starting at −300 mV and scanned at rates of 500, 300, and 100 mV/s.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the NIH (R01-CA115531, P41-EB015908) and, in part, by the Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center through an NCI Cancer Center Support Grant, 1P30-CA142543, and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (AT-584) is gratefully acknowledged (ADS). MJA gratefully acknowledges support from the NIH (R01-EB013663). KNG gratefully acknowledges support from Moncrief Cancer Institute (INFOR), TCU Research and Creative Activities Fund, and TCU Andrews Institute for Education.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is given via a link at the end of the document

References

- 1.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viswanathan S, Kovacs Z, Green KN, Ratnakar SJ, Sherry AD. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2960–3018. doi: 10.1021/cr900284a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Evans WJ. Coord Chem Rev. 2000;206:263–283. [Google Scholar]; b) MacDonald MR, Bates JE, Ziller JW, Furche F, Evans WJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:9857–9868. doi: 10.1021/ja403753j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Toth E, Burai L, Merbach AE. Coord Chem Rev. 2001;216–217:363–382. [Google Scholar]; b) Lenora CU, Carniato F, Shen Y, Latif Z, Haacke EM, Martin PD, Botta M, Allen MJ. Chem Eur J. 2017 doi: 10.1002/chem.201702158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Yee EL, Cave RJ, Guyer KL, Tyma PD, Weaver MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:1131–1137. [Google Scholar]; b) Gansow OA, Kausar AR, Triplett KM, Weaver MJ, Yee EL. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:7087–7089. [Google Scholar]; c) Gamage ND, Mei Y, Garcia J, Allen MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:8923–8925. doi: 10.1002/anie.201002789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Garcia J, Allen MJ. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2012;2012:4550–4563. doi: 10.1002/ejic.201200159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Pearson RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1963;85:3533–3539. [Google Scholar]; b) Kuda-Wedagedara ANW, Wang C, Martin PD, Allen MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:4960–4963. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b02506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Parr RG, Pearson RG. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:7512–7516. [Google Scholar]; d) Shannon RD. Acta Crystallogr, Sect A: Cryst Phys, Diffr, Theor Gen Crysallogr. 1976;a32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Ekanger LA, Mills DR, Ali MM, Polin LA, Shen Y, Haacke EM, Allen MJ. Inorg Chem. 2016;55:9981–9988. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b00629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Funk AM, Clavijo Jordan V, Sherry AD, Ratnakar SJ, Kovacs Z. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:5024–5027. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekanger LA, Polin LA, Shen Y, Haacke EM, Allen MJ. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2016;11:299–303. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekanger LA, Polin LA, Shen Y, Haacke EM, Martin PD, Allen MJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54:14398–14401. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ekanger LA, Ali MM, Allen MJ. Chem Commun. 2014;50:14835–14838. doi: 10.1039/c4cc07027e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekanger LA, Basal LA, Allen MJ. Chem Eur J. 2017;23:1145–1150. doi: 10.1002/chem.201604842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chlistunoff J, Galus Z. J Electroanal Chem. 1985;193:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regueiro-Figueroa M, Barriada JL, Pallier A, Esteban-Gomez D, Blas AD, Rodreguez-Blas T, Toth E, Platas-Iglesias C. Inorg Chem. 2015;54:4940–4952. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Soderholm L, Antonio MR, Skanthakumar S, Williams CW. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7290–7291. doi: 10.1021/ja025821d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Antonio MR, Soderholm L. J Clust Sci. 1996;7:585–591. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botta M, Ravera M, Barge A, Bottaro M, Osella D. Dalton Trans. 2003:1628–1633. [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Green KN, Jeffery SP, Reibenspies JH, Darensbourg MY. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:6493–6498. doi: 10.1021/ja060876r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Green KN, Brothers SM, Jenkins RM, Carson CE, Grapperhaus CA, Darensbourg MY. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:7536–7544. doi: 10.1021/ic700878y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lincoln KM, Offutt ME, Hayden TD, Saunders RE, Green KN. Inorg Chem. 2014;53:1406–1416. doi: 10.1021/ic402119s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Do QN, Ratnakar JS, Kovács Z, Sherry AD. ChemMedChem. 2014;9:1116–1129. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Desreux JF. Inorg Chem. 1980;19:1319–1324. [Google Scholar]; b) Green KN, Viswanathan S, Rojas-Quijano FA, Kovacs Z, Sherry AD. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1648–1655. doi: 10.1021/ic101856d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kovacs Z, Sherry AD. Synthesis. 1997;1997:759–763. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller KJ, Saherwala AA, Webber BC, Wu Y, Sherry AD, Woods M. Inorg Chem. 2010;49:8662–8664. doi: 10.1021/ic101489t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aime S, Botta M, Ermondi G. Inorg Chem. 1992;31:4291–4299. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burai L, Tóth É, Moreau G, Sour A, Scopelliti R, Merbach AE. Chem Eur J. 2003;9:1394–1404. doi: 10.1002/chem.200390159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tropiano M, Blackburn OA, Tilney JA, Hill LR, Placidi MP, Aarons RJ, Sykes D, Jones MW, Kenwright AM, Snaith JS, Sørensen TJ, Faulkner S. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:16566–16571. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.