Abstract

Background:

Depression is a significant public health concern in India, associated with a large treatment gap. Assessing perceptions of Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) on depression can be invaluable as they are selected to work at the interface between their own communities and the health-care delivery system.

Aims and Objectives:

This study aimed at utilizing a qualitative approach to examine the ASHAs’ understanding of depression, their mental health-care practices specific to depression, and their capacity-building needs with regard to identification and helping persons with depression.

Subjects and Methods:

A cross-sectional qualitative study using two focus group discussions was conducted. The sample comprised 14 ASHAs in the age range of 25–45 years from Bengaluru urban district. The data were analyzed manually by the method of directed content analysis.

Results:

The ASHAs were found to have inadequate knowledge of the signs and symptoms of depression, its biopsychosocial nature, and its impact on functioning. Causation of depression was narrated in terms of psychosocial stressors. The majority expressed the need for primarily psychosocial interventions for depression. All participants reported their motivation to obtain training in identifying persons with depression and providing simple psychosocial intervention for them.

Conclusion:

This study indicates that ASHAs have poor knowledge of depression, which could be leading to its low recognition and treatment in the communities they work in. They are therefore likely to benefit from capacity building on depression which includes familiar nomenclature, biopsychosocial elucidation of the illness, life-span approach, understanding of its impact on various domains of functioning, and the treatments available.

Keywords: Accredited Social Health Activist, capacity building, community health workers, depression, primary health care

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a significant public health concern in India as it affects a large proportion of persons in the community, as reported by the recent National Mental Health Survey of India 2015–2016 in which it found that one in forty persons and one in twenty persons suffer from the past and current depression, respectively.[1] Indian research on depression indicates that it leads to significant disability, dysfunction, and poor quality of life for the person with depression and it also causes a significant burden on the caregivers.[2] In addition, research in India has pointed to the high level of comorbidity of depression with both mental and physical illnesses, especially in elderly individuals with depression.[2]

There is a large treatment gap of 85.2% for major depressive disorder.[1] This has been attributed to multiple factors including the lack of awareness and affordability of care, which differs in rural and urban areas.[1] Public health researchers and practitioners have advocated task sharing, i.e., delivery of mental health-care services by nonspecialist health workers in community settings as a method to bridge this treatment gap.[3,4] On examination of perceptions of stakeholders, namely, primary care service providers, community members, and service users, in low- and middle-income countries, it was found that task sharing of mental health-care services is acceptable and feasible.[5]

Indian research has estimated the prevalence rate of depression in primary care centers as 21%–40.45%.[2] One of the major barriers for the treatment of depression in primary care settings in India is its low recognition.[6,7] This low recognition could be associated with a lack of knowledge with regard to depression, as shown in a study in which community health workers were found to have never heard about depression and had significant difficulty in defining clinical depression.[8] Mental health training program for community health workers in India has been found to be effective in improving some aspects of mental health literacy.[9] Research has shown that collaborative stepped-care intervention which is led by trained lay health counselors can lead to an improvement in recovery from depressive and anxiety disorders among patients utilizing primary health-care services.[10,11,12]

In the public primary health-care facilities in India, the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) are trained female community health activist working in villages. ASHA is recruited from the village itself and works as an interface between the village community and the public health system.[13] The present study is part of a larger study that is aimed at developing a brief psychoeducational-intervention training video on depression for ASHA. In the present study, we employed a qualitative approach to understand the perspectives of ASHAs with regard to their understanding of depression, the mental health-care practices specific to persons with depression that they utilize in the community and their capacity-building needs with regard to identification and helping persons with depression.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Design

A cross-sectional qualitative study as part of a larger study called the “ASHA ViDe Study” on the development of brief psychoeducational-intervention training video on depression for ASHA was used. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

Sample

The sample comprised 14 ASHAs (age range: 25–45 years) from Bengaluru urban district. The sampling method was purposive. The ASHAs who provided consent to participate in the study were recruited.

Procedure

Two focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in Kannada with eight and six ASHAs in each group, respectively. The FGDs were conducted over approximately 2 h and each FGD had comprised two moderators, with experience in qualitative research methodology. An FGD guide was prepared by the first author, focusing on examining the understanding of depression, its symptoms, causes, impact and treatment, and type of mental health services that the ASHAs provide specific to persons with depression. It also included their experiential account of interacting with persons with depression in the community and their specific needs and areas with regard to depression that they wish to learn more on.

Analysis

The moderators took notes of the FGDs. The data were analyzed manually by the method of directed content analysis,[14] in which the transcript of the two groups was first examined separately to identify the key themes with frequency counts being noted, and then collated under the broad predetermined themes derived by the researchers, namely, exploring the ASHAs understanding and beliefs regarding signs and symptoms of depression, causes of depression, impact of depression, mental health-care practices with regard to depression and capacity-building needs with regard to depression.

RESULTS

The average age of the ASHAs was 32 years (standard deviation = 5.58). All except one was married. The majority (n = 8) had studied up to the 10th standard. Their years of experience of working as ASHAs ranged from 1 to 7 years. The subthemes that were identified under the broad predetermined themes are described below:

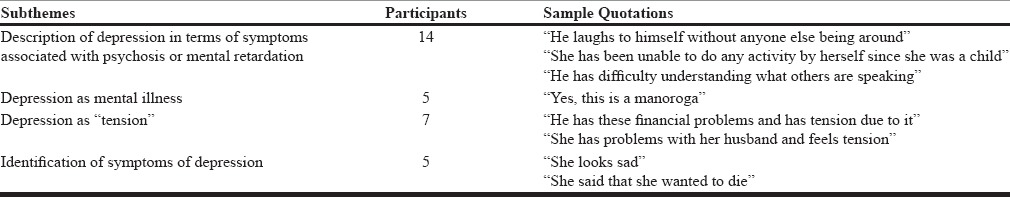

Theme 1 - Signs and symptoms of depression

The ASHAs did not understand the term “depression.” In terms of signs and symptoms of depression, all of them described depression in terms of symptoms associated with psychosis or mental retardation. It was only on probing and providing cues; some (n = 5) were able to explain depression as sadness. They recalled one or two persons whom they felt could have suffered from depression. The symptoms identified in these individuals were that they “preferred to be alone,” “wanted to die,” and had “lost hopes and aspirations.” Four of the participants gave the term “khinnathe” for “depression” in the Kannada language. A few (n = 4) of them identified it as “manoroga,” which is the term for “mental illness” in the Kannada language. Half of the participants considered depression to be synonymous with the person having “tension.”

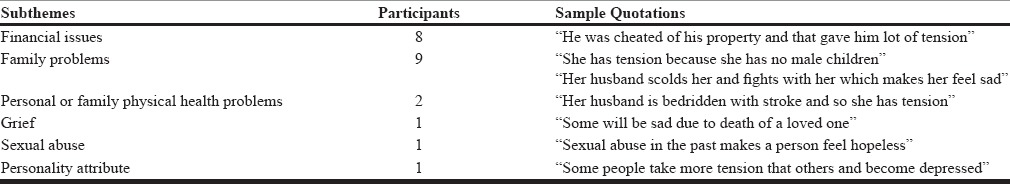

Theme 2 - Causes of depression

The ASHAs explained the causation of depression as psychosocial stressors such as poverty, financial difficulties, being cheated in property, unemployment, staying alone without children, tension due to no male children, children being troublesome, grief due to death of a loved one, sexual abuse in the past, family health problems, and physical health problems. A few (n = 6) opined that people in their village also hold similar views on depression.

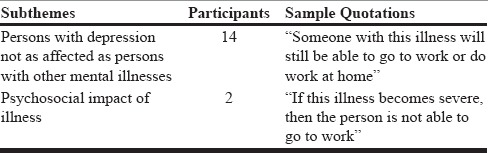

Theme 3 - Impact of depression

All the participants expressed the view that persons with depression may not be as severely ill or affected as persons with other mental illnesses. It is to be noted here that the other mental illnesses that they were aware of included psychosis and mental retardation. However, participants stated that in case depression is severe in nature, it impacts the person's ability to do work and to look after their children.

Theme 4 - Mental health-care practices with regard to depression

One of the ASHAs expressed the difficulty in detecting depression as it could be easily mistaken for other ailments. Another explained that depression may not be detected as easily as other illnesses since persons with depression are still able to function and to do work. One participant did not think that there was a need for persons with depression to seek mental health treatment. Most (n = 13) participants were in agreement that persons with depression need treatment even though they may not talk about it or express the need. They conjectured that if they speak with and counsel and advise a person with depression about their problems, then she/he will feel better. Thus, suggesting that support was important. One participant said that the person with depression needs to be advised regarding following a daily routine. A few (n = 3) who associated depression with domestic violence emphasized that the ASHAs need to counsel family members regarding ending of domestic violence. Some (n = 2) of the ASHAs also discussed the need for them to be trusted by the person with depression and their family members for them to make an impact while talking to them. Some (n = 5) of the ASHAs opined that if the person with depression was still not feeling better after they had spoken with them, then they need to refer them to a psychiatric hospital. All ASHAs agreed that persons in the community usually do not think that depression needs treatment and they expressed the need to create awareness in the community regarding depression and its treatment.

Theme 5 - Capacity-building needs with regard to depression

All the ASHAs expressed the need for training to work with persons with depression in the community and to create awareness about depression among the community members. As one of them indicated that there may be a large number of people who would be affected by depression in the villages, there are so many problems that are faced by people. Even though a part of many government initiatives, all of them expressed motivation to be trained in identification and management of depression. One of them pointed out that since they “anyway go to houses to meet people,” a few more inquiries with regard to depression will help in identifying persons with depression and consequently their treatment.

DISCUSSION

The present study was aimed at examining the understanding ASHAs had about depression as a mental health condition and was part of a larger study aimed at developing training material.

The results of this study revealed that the ASHAs did not understand the term “depression” and described depression in terms of symptoms associated with psychosis or mental retardation [Table 1]. A few (n =5) of them though, with probing and cues from the moderators, were able to explain depression as sadness and reported of persons in the community who could probably have had depression. The symptoms identified in them were that they “preferred to be alone”, “wanted to die” and had “lost hopes and aspirations”. A few (n = 4) gave the term “khinnathe” in the Kannada language for ‘depression’. Interestingly, the ASHAs did not report the identification of depression through somatic symptoms, which is the most common and primary presentation for depression in primary care.[6,7] This is similar to findings from a study carried out in Gujarat, India, in which majority of the community health workers reported to have never heard about depression and had significant difficulty in defining clinical depression.[8] This thus indicates that the participants may have difficulty in identification of persons with depression in the community due to their lack of knowledge of the signs and symptoms of depression. In addition, as the participants did not identify depression-related issues in children, elderly, and postpartum women, it is possible that in these vulnerable groups, symptoms may go unrecognized. Only a few (n = 5) of the participants considered “depression” to be a mental illness, while half of them considered depression to be synonymous with the person having “tension.” These findings are corroborated by another study in which persons with common mental disorders attending primary care labeled their illness with terms such as “tension” or “worry” and did not think that they had a “mental disorder.”[7] These findings thus suggest that while training ASHAs or other community health workers, it may be preferable to utilize nomenclature that they are aware of and are able to identify with. Furthermore, it needs to be explored if the terms such as “tension” or “worry” are preferred as they are less stigmatizing than a diagnosis of “depression.”

Table 1.

Signs and symptoms of depression (Theme 1)

The participants in this study explained the causation of depression in terms of psychosocial stressors such as poverty, financial difficulties, being cheated in property, unemployment, staying alone without children, tension due to no male children, children being troublesome, grief due to death of a loved one, sexual abuse in the past, family health problems, and physical health problems [Table 2]. This is similar to findings from another study in which majority of the persons with common mental disorders attending primary care attributed their illness to psychosocial factors.[7] This indicates that the ASHAs’ explanatory model of depression does not include a biological explanation of the illness.

Table 2.

Causes of depression (Theme 2)

With regard to the impact of depression, the ASHAs expressed the view that persons with depression may not be as severely ill or affected as persons with other mental illnesses [Table 3]. Furthermore, they opined that in case depression was severe in nature, it would impact the person's ability to do work and to look after their children. This suggests that they did not understand the biopsychosocial nature of depression and its impact on various domains of functioning. Furthermore, none of them pointed out to the possibility of suicide being associated with depression.

Table 3.

Impact of depression (Theme 3)

The majority of the participants acknowledged that it is difficult to identify depression as the level of severity of symptoms is less as compared to other mental illnesses [Table 4]. All except one agreed that mental health intervention is needed for depression. They were primarily of the opinion that supports in the form of speaking with and counseling and advising the person with depression or his/her family members will help the person recover. Trust as an important factor while counseling was elaborated on by two of the ASHAs. The findings thus indicate that the ASHAs seemed to be familiar with “speaking to” as an intervention for depression, but it was unclear if they understood them in the format of standard psychotherapeutic interventions requiring knowledge of methods and techniques since several times they tended to suggest that they would be “advising” the patient and family members. With regard to referral, some (n = 5) of the ASHAs remarked that if the person with depression were still not feeling better after they had talked to them, then they would refer them to a psychiatric hospital. The low numbers of ASHAs considering referral for depression could be associated with their explanatory model of depression being primarily psychosocial in nature. Furthermore, they did not seem to have a clear understanding of the mental health professionals of various disciplines who are part of the mental health delivery system indicating that they may have difficulty making appropriate referrals.

Table 4.

Mental health-care practices with regard to depression (Theme 4)

An interesting and encouraging finding was that all participants reported their motivation to obtain training in identifying and providing simple psychosocial intervention for persons with depression and did not see this as an additional burden as they said that they were anyway making home visits [Table 5]. They expressed the need to create awareness in the community regarding depression and its treatment as persons in the community usually do not think that depression needs treatment.

Table 5.

Capacity-building needs with regard to depression (Theme 5)

The study has limitations in terms of the generalizability of findings due to its small sample size and circumscribed geographical area from which the sample was recruited. The implications of the study are that capacity building for ASHAs on depression needs to include nomenclature that they are familiar with, biopsychosocial understanding of depression, life-span approach, understanding of the impact of depression on various domains of functioning, and the treatments available for depression.

CONCLUSION

This study indicates that ASHAs who are the frontline health workers in the community have poor knowledge of depression, which could be leading to its low recognition and treatment. They will therefore benefit from capacity building, which is tailor-made to their health-care provision needs as well as acknowledges their explanatory model of depression.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the support of the Taluk Health Officer and the PHC Medical Officer from the Bengaluru urban district for conducting this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gururaj G, Varghese M, Benegal V, Rao GN, Pathak K, Singh LK, et al. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, NIMHANS; 2016. National Mental Health Survey of India, 2015-2016: Summary. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grover S, Dutt A, Avasthi A. An overview of Indian research in depression. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52(Suppl 1):S178–88. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.69231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mendenhall E, De Silva MJ, Hanlon C, Petersen I, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: Stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2014;118:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin G, Shah S, Vankar GK. The prevelance and recognition of depression in primary care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:364–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew G, Cohen A, Salgaonkar S, Patel V. The explanatory models of depression and anxiety in primary care: A qualitative study from India. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:499. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almanzar S, Shah N, Vithalani S, Shah S, Squires J, Appasani R, et al. Knowledge of and attitudes toward clinical depression among health providers in Gujarat, India. Ann Glob Health. 2014;80:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong G, Kermode M, Raja S, Suja S, Chandra P, Jorm AF. A mental health training program for community health workers in India: Impact on knowledge and attitudes. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Araya R, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Gaete J, Rojas M, Simon G, et al. Treating depression in primary care in low-income women in Santiago, Chile: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention led by lay health counsellors for depressive and anxiety disorders in primary care in Goa, India (MANAS): A cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:2086–95. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chowdhary N, Anand A, Dimidjian S, Shinde S, Weobong B, Balaji M, et al. The Healthy Activity Program lay counsellor delivered treatment for severe depression in India: Systematic development and randomised evaluation. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208:381–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.161075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Mission. About Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA) [Last retrieved on 2017 Mar 01]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.gov.in/communitisation/asha/about-asha.html .

- 14.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]