Abstract

The plant-specific WRINKLED1 (WRI1) is a member of the AP2/EREBP class of transcription factors that positively regulate oil biosynthesis in plant tissues. Limited information is available for the role of WRI1 in oil biosynthesis in castor bean (Ricinus connunis L.), an important industrial oil crop. Here, we report the identification of two alternatively spliced transcripts of RcWRI1, designated as RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B. The open reading frames of RcWRI1-A (1341 bp) and RcWRI1-B (1332 bp) differ by a stretch of 9 bp, such that the predicted RcWRI1-B lacks the three amino acid residues “VYL” that are present in RcWRI1-A. The RcWRI1-A transcript is present in flowers, leaves, pericarps and developing seeds, while the RcWRI1-B mRNA is only detectable in developing seeds. When the two isoforms were individually introduced into an Arabidopsis wri1-1 loss-of-function mutant, total fatty acid content was almost restored to the wild-type level, and the percentage of the wrinkled seeds was largely reduced in the transgenic lines relative to the wri1-1 mutant line. Transient expression of each RcWRI1 splice isoform in N. benthamiana leaves upregulated the expression of the WRI1 target genes, and consequently increased the oil content by 4.3–4.9 fold when compared with the controls, and RcWRI1-B appeared to be more active than RcWRI1-A. Both RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B can be used as a key transcriptional regulator to enhance fatty acid and oil biosynthesis in leafy biomass.

Keywords: RcWRI1, alternative splice form, fatty acid and oil biosynthesis, castor (Ricinus communis L.), tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana L.)

1. Introduction

Vegetable oils stored in plant seeds are predominantly composed of triacylglycerols (TAGs), glycerol esters with three fatty acids that serve as an energy reserve for catabolism during germination [1]. In addition to use as human food, plant oils are also important as renewable feedstocks for biofuel production, which could potentially decrease our dependence on fossil oil [2,3]. As such, developing high-yielding oil crops and creating new oil production platforms are needed to ensure sustainable supply of global vegetable oils. Understanding the molecular and biochemical mechanisms underlying fatty acid (FA)/oil biosynthesis and regulation is important to undertake this endeavor.

Current knowledge of the FA and TAG biosynthesis has been mainly obtained from the study of the model plant Arabidopsis [4,5]. These studies have revealed a series of enzymes that are involved in converting photosynthate sucrose to TAG [6,7,8]. The biosynthetic steps are spatially separated between different organelles and regulated by various biochemical mechanisms [9]. In particular, sucrose is converted to pyruvate (Pyr) via cytosolic or plastidic glycolytic pathways, which provides Pyr as the precursor for the acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA) molecules destined to FA synthesis in plastids. FAs with different carbon-chain length are subsequently transported out from the plastid to the cytoplasm as acyl-CoAs. At endoplasmic reticulum (ER), acyl-CoAs are used to acylate glycerol-3-phosphate (G3P) backbone, either by Kennedy pathway to produce TAGs or by acyl exchange between lipids [10,11]. The resulting TAGs within the ER membrane are then budded off as specialized structures called oil bodies surrounded by a single-layer phospholipids and proteins.

WRINKLED1 (WRI1), a member of the APETALA2/ethylene-responsive element binding protein (AP2/EREBP) transcriptional factor family [12], has been identified as a master regulator in the control of oil biosynthesis. Loss-of-function mutants of WRI1 exhibited wrinkled and incompletely filled seeds with an 80% reduction of total TAGs when compared with the wild-type seeds [13]. WRI1 coordinates expression of the gene cluster essential in FA biosynthesis, including plastid pyruvate kinase beta subunit 1 (PKp-β1), pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit (PDH-E1α), biotin carboxyl carrier protein isoform 2 (BCCP2), acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase), sucrose synthase 2 (SUS2), and 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase 1 (KAS1) [14,15,16,17]. The promoter regions of these genes contain the AW-box (CnTnG(n)7CG) or 15-bp element (CAAAAG(T/G)AGG(G/A)APTT) which serve as the WRI1-binding sites [18].

WRI1 was first discovered in Arabidopsis [12], and its orthologs have been identified from oil seed crops such as rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) [19], corn (Zea mays L.) [20], and Camelina sativa [21], as well as from plants rich in oil in non-seed tissues such as oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq) [22,23], poplar (Populus trichocarpa L.) [24], Brachypo diumdistachyon [25], and Cyperu sesculentus [26]. Overexpression of these diverse WRI1 genes has led to significant increases in oil accumulation [21,23,25,26], providing a new tool for developing high-yielding oilseeds and oil-enriched non-seed biomass.

Recently, several homologous genes of AtWRI1 (e.g., AtWRI2, AtWRI3 and AtWRI4) were also characterized; these genes show a similar function as AtWRI1 although their expression patterns were different [16,23]. Moreover, three alternative splice forms (At3g54320.1-3) are predicted for AtWRI1 and only splice form 3 (At3g54320.3) is present in multiple Arabidopsis tissues [23]. It is currently unknown whether all the three AtWRI1 splice variants play roles in plant fatty acid biosynthesis.

Castor bean (Ricinus connunis L.) is an important industrial oil crop rich in ricinoleic acid (90% of total oil) [27,28]. However, regulatory networks underlying oil biosynthesis and accumulation have not yet been well understood in this species [29]. In this study, we identified two alternative splice variants for the castor bean WRI1 gene (RcWRI1), namely RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B. The two transcript isoforms displayed differential expression patterns in various castor tissues. Expression of either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B increased seed oil accumulation in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 mutant. Furthermore, transient expression of individual RcWRI1 isoforms in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves significantly activated the WRI1 target gene expressions, leading to a great enhancement of oil/TAG accumulation in leaf tissues, with RcWRI1-B being more active than RcWRI1-A. Our data provide novel insights into the WRI1-mediated regulatory networks responsible for FA biosynthesis in plant, and suggest that both RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B could be potentially used for engineering high-oil production crops.

2. Results

2.1. Molecular Characterization of Castor RcWRI1

To identify the WRI1 ortholog in castor bean, a BLASTP analysis with an e-value threshold of 1.0 × 10−6 was performed against the castor bean genome database using the protein sequence of AtWRI1 as a query. The highest score was obtained for the gene (LOC8283400), which we tentatively termed RcWRI1. A primer pair was designed based on the open reading frame (ORF) of this gene, which was subsequently used to amplify the cDNA encoding RcWRI1 by RT-PCR. This experiment identified two RcWRI1 cDNAs with different length. Sequence analysis revealed that the long form (1341 bp) of RcWRI1 was nearly identical with the short form (1332 bp) of RcWRI1, with the short form lacking a stretch of 9-bp nucleotides encoding “VYL” (Figure 1). The long and short cDNAs of RcWRI1 were named RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B, respectively.

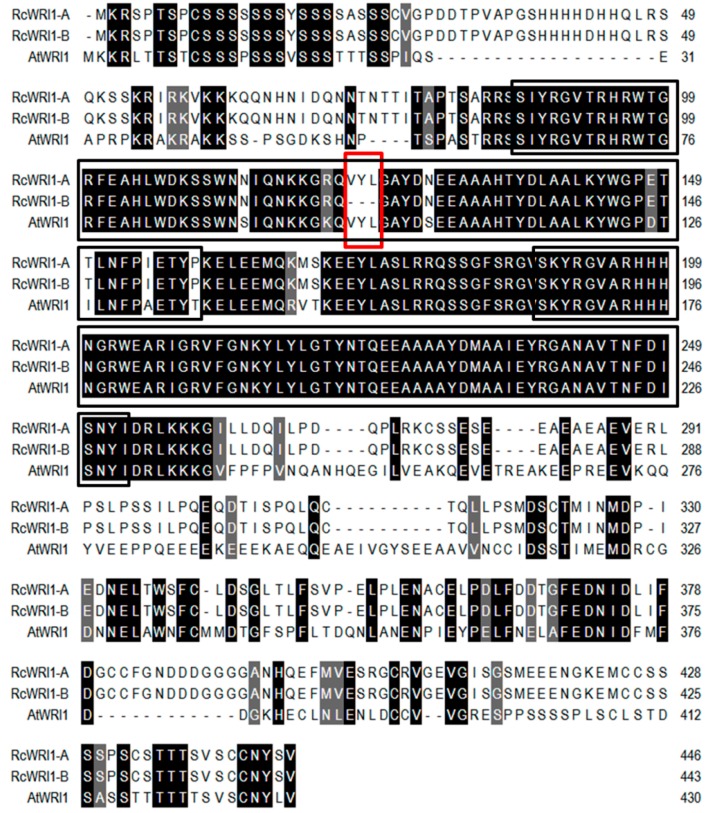

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of two RcWRI1 and AtWRI1 protein isoforms. The alignment was performed by the ClustalW program. Most of the difference between protein sequences of RcWRI1s and AtWRI1 occurs at the C-terminal half of the protein. “VYL” motif in AtWRI1 and RcWRI1-A is absent in RcWRI1-B. The high and low consensus amino acid residues are denoted by black and gray colors, respectively. Two AP2 domains are marked by black boxes. The sequence “VYL” present in the first AP2 domain are marked by red box.

In order to verify the two alternate splice forms of RcWRI1, we aligned the RcWRI1 genomic sequence and two RcWRI1 cDNA sequences (Figure S1). The genomic sequences that match the cDNA are exons, and the alignment gaps are introns. Putative intron boundaries conform to the GT-AG rule [30]. Exon 3 consists of 9 bp in RcWRI1 gene, which is spliced out in RcWRI1-B where exon 2 directly links to exon 4. Thus, RcWRI1-B is 9-bp shorter than RcWRI1-A (Figure S2). Therefore, RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B are the alternative splice forms from the same RcWRI1 gene.

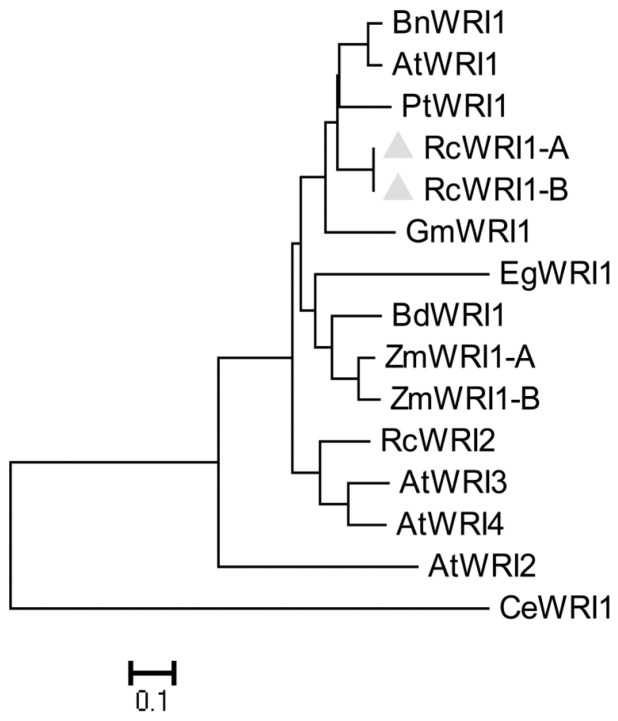

Further alignment of RcWRI1-A, RcWRI1-B and AtWRI1 indicated that these three proteins share 90% sequence similarity in the two highly conserved AP2 domains at their N-termini (Figure 1). However, the C-terminal regions are highly diverged, with only 31% identity. In addition, the sequence “VYL” present in the first AP2 domain of WRI1 protein, which is essential for its function, is conserved in AtWRI1 and RcWRI1-A, whereas this important motif was absent in RcWRI1-B (Figure 1). To clarify the phylogenetic relationship between the two RcWRI1 isoforms and AtWRI1, we included the related Arabidopsis proteins AtWRI2, AtWRI3, and AtWRI4, as well as other WRI homologous proteins from different species. Phylogenetic analysis by MEGA6 showed that RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B was the closest to AtWRI1 (Figure 2), because they fell into the same clade as AtWRI1 and BnWRI1. AtWRI1 is the only one responsible for TAG accumulation in seeds among members of AtWRI1 family [16].

Figure 2.

Phylogenic tree of RcWRI1s and WRI1 homologous from other plant species. Phylogenetic tree was generated using MEGA6 by the neighbor-joining method. Percentage values on each branch represent the corresponding bootstrap probability. Protein sequences used for phylogenic analysis included BnWRI1 (ADO16346), ZmWRI1-A (ACG32367.1), ZmWRI1-B(AIB05036.1), CeWRI1 (SRX1079431), PtWRI1 (XP_002311921.2), GmWRI1 (XP_006596986.1), BdWRI1 (Brai4g43877), AtWRI1 (AAP80382), AtWRI2 (ABG25074), AtWRI3 (NP_001320852.1), AtWRI4 (ABK32182.1), RcWRI2 (BAM75179.1) and EgWRI1 (AHX71676.1). The two RcWRI1s protein are highlighted by the grey arrowheads.

2.2. Expression Profiles of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in Various Castor Organs

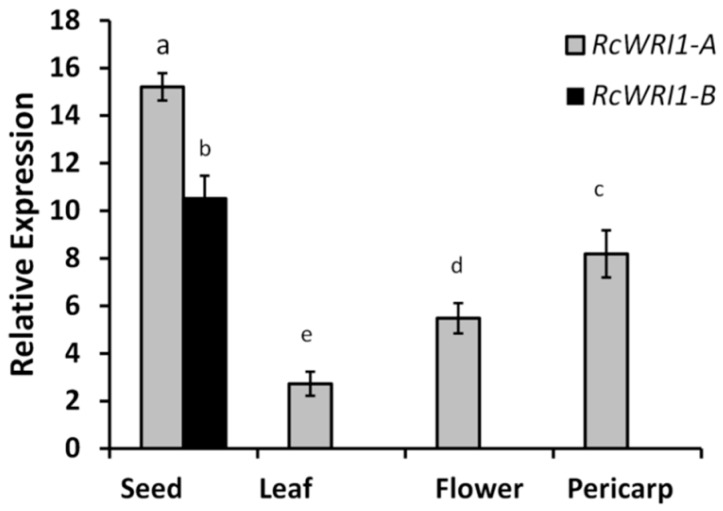

We assessed the expression of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in different organs of castor bean plants by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). The transcript-specific primers (Figure S3A) were designed to distinguish RcWRI1-A from RcWRI1-B. RcWRI1-A was expressed in all organs tested (Figure 3), with the highest expression in developing seeds (30 DAF, days after florescence) and the lowest in the leaf. However, RcWRI1-B was only expressed in developing seeds. These results indicate that both RcWRI1 isoforms are actively transcribed during seed development. Similar to AtWRI1 in Arabidopsis siliques [12], the predominant expression of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in castor seed suggests that these two castor RcWRI1 isoforms function importantly in seed development. RcWRI1-B is unlikely to play a biological role in castor leaf, flower, and pericarp because of no expression was detected in these organs.

Figure 3.

Expression of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in major castor bean organs. Expression profiles were determined by qRT-PCR using total RNA from leaves, flowers, pericarps, and developing seeds. RcActin was used as an internal control. Each value is the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. Letters a, b, c, d, e indicate significant differences at the level of p < 0.05 according to the Tukey’s test.

2.3. Overexpression of Individual RcWRI1 Splice Forms Restored Seed Total Lipid Content in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 Mutant

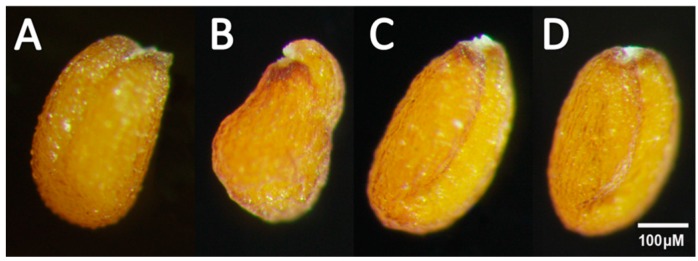

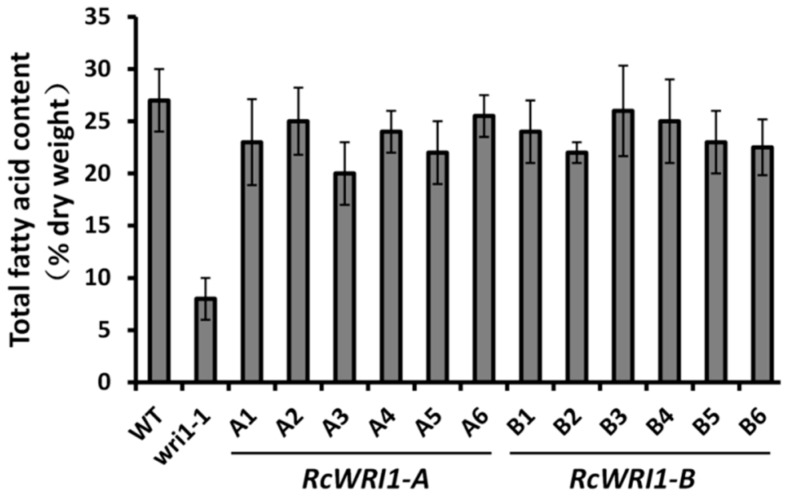

In order to investigate the function of the RcWRI1s, we separately overexpressed RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B under a seed-specific Gly promoter in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 loss-of-function mutant. A microscopic observation of mature dry seeds showed that transgenic wri1-1 plants expressing RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B displayed a non-wrinkled phenotype (Figure 4). We further measured the fatty acid content in seeds of transgenic lines. Overexpression of RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B restored total fatty acid content in seeds to the wild-type level (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B complemented the Arabidopsis wrinkled seed phenotype. The seed phenotype was examined by a stereo microscope. (A) Wild type; (B) wri1-1 mutant; (C) wri1-1 expressing RcWRI1-A; (D) wri1-1 expressing RcWRI1-B.

Figure 5.

Total fatty acid content in seeds of Arabidopsis wildtype, wri1-1 mutant, and the mutants expressing either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B. Total fatty acids were extracted from the seed and transmethylated, followed by gas chromatography analysis. Fatty acid content was expressed as the percentage of seed dry weight. Each value is the mean ± SD of six biological replicates.

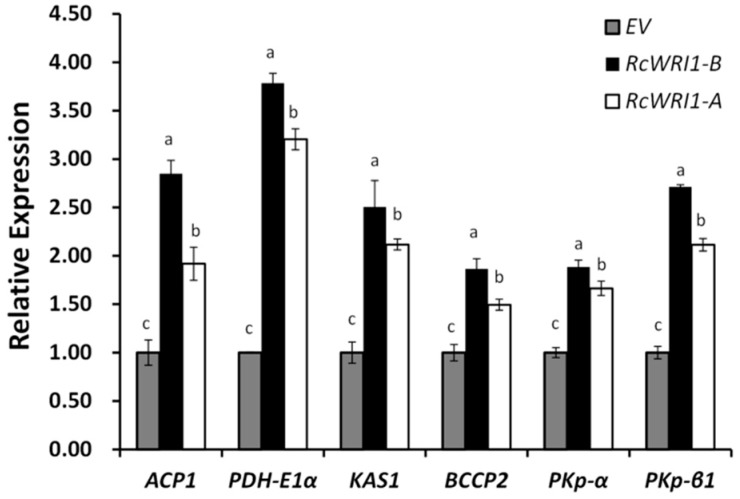

2.4. Transient Expression of RcWRI1s Enhances the Expression of the Downstream Genes in the Fatty Acid Biosynthesis Pathway

To investigate the function of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in gene regulation, we further examined the expressions of the putative target genes in N. benthamiana leaves where RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B were transiently expressed (Figure S3B). These putative target genes include plastid pyruvate kinase beta subunit 1 (PKp-β1), pyruvate kinase alpha subunit (PKp-α), acyl carrier protein 1 (ACP1), pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit (PDH-E1α), biotin carboxyl carrier protein isoform 2 (BCCP2), and 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase 1 (KAS1) [14,15]. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that expression of these target genes was significantly increased in leaves either expressing RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B relative to the empty-vector (EV) controls (Figure 6). Notably, expression of PDH-E1α was three times higher than in the control. Moreover, RcWRI1-B appeared to show a stronger activity in promoting the target gene expression than RcWRI1-A.

Figure 6.

Expression profiles of WRI1 target genes in tobacco leaves expressing either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B. Total RNA was isolated from the leaves expressing each of RcWRI1s, and used for qRT-PCR analysis. The primers were designed based on the coding sequences of PKp-β1, PKp-α, ACP1, PDH-E1α, BCCP2, and KAS1 of N. benthamiana. EV indicates empty-vector control. NbActin was used as an internal control. Each value is the mean ± SD of six biological replicates. Letters a, b, c indicate a significant difference at the level of p < 0.05 according to the Tukey’s test.

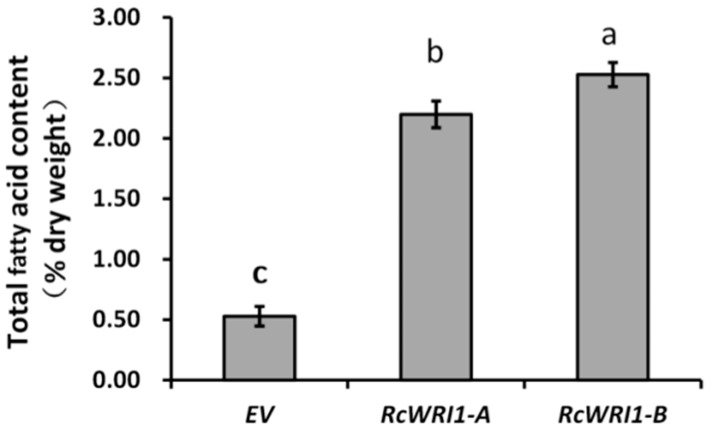

2.5. Ectopic Expression of RcWRI1s Increases Total Lipid Content in N. benthamiana Leaves

To characterize the function of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in fatty acid biosynthesis and oil accumulation, we tested whether the expression of each castor RcWRI1 isoform could lead to the increase of the total lipid content in transformed N. benthamiana leaves. For this purpose, we expressed the genes under the control of the CaMV35S promoter through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. The infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves were subjected to the analysis of total lipid content. As shown in Figure 7, total lipid content in the leaves expressing each of RcWRI1s was remarkably higher than that in the control leaves infiltrated with the empty vector, with leaves expressing RcWRI1-B showing a higher level of oil concentration (2.5% of leaf dry weight). These results indicate that both RcWRI1 isoforms function actively in induction of fatty acid/oil accumulation in heterogenous leaves when transiently expressed. Again, RcWRI1-B is more active than RcWRI1-A in this regard.

Figure 7.

Total fatty acid content in N. benthamiana leaves expressing each of RcWRI1s. Fatty acids were extracted from the leaf samples and then transmethylated, followed by gas chromatography analysis. Fatty acid content was expressed as the percentage of leaf dry weight. EV indicates empty-vector control. Each value is the mean ± SE of twelve biological replicates. Letters a, b, c indicate a significant difference at the level p < 0.05 according to the Tukey’s test.

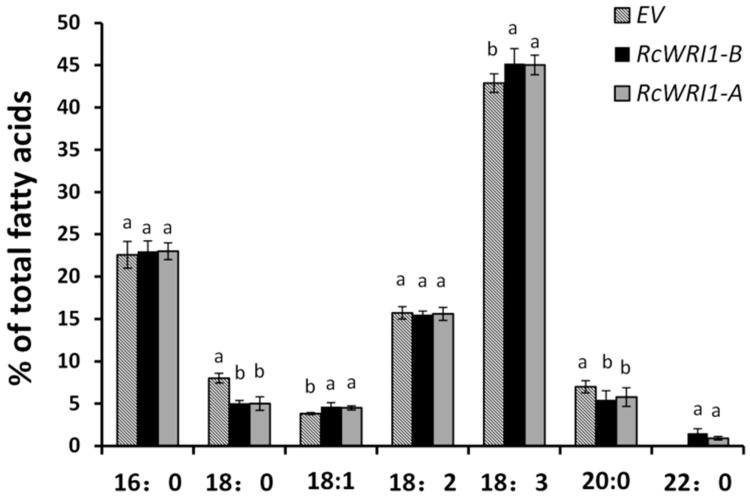

2.6. Ectopic Expression of RcWRI1s Changes Fatty Acid Profiles in N. benthamiana Leaves

To examine the effects of RcWRI1 expression on fatty acid composition, we further analyzed the fatty acid profiles in N. benthamiana leaves transformed with RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B. As shown in Figure 8, expression of either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B induced a subtle change in the fatty acid composition in the leaves, such as the increases in 18:1, 18:3 and 22:0 fatty acids when compared with the controls. However, 18:0 and 20:0 contents were reduced in the RcWRI1-expressed leaves. No obvious change was detected for the 16:0 and 18:2 fatty acid contents between the RcWRI1-expressing leaves and the controls. No significant difference in this regard was detected between RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B. Unexpectedly, a new long chain fatty acid 22:0 was synthesized and accumulated in the leaves expressing each of RcWRI1s, but not in the vector controls. The possible reason may be that RcWRI1 overexpression increases the activity of fatty acid elongases (FAE) [18].

Figure 8.

Fatty acid profiles in N. benthamiana leaves expressing each of RcWRI1s. Fatty acids were extracted from the leaf samples and then transmethylated, followed by gas chromatography analysis. Fatty acid content was expressed as the percentage of leaf dry weight. EV indicates empty-vector control. Each value is the mean ± SE of twelve biological replicates. Letters a, b indicate significant differences at the level p < 0.05 according to the Tukey’s test.

3. Discussion

3.1. Castor RcWRI1 Expresses Two Alternative Splice Forms with Tissue-Specific Patterns

Multiple isoforms of WRI1 were recently identified despite the majority of plants were detected to have a single WRI1 gene. For example, maize genome contained two isoforms, ZmWRI1a and ZmWRI1b [20]. Three functional CsWRI1 isoforms (CsWRI1A, B, and C) were discovered in camelina genome [21]. In addition to AtWRI1, AtWRI2, 3, and 4 were identified to have the similar function as AtWRI1 despite of their different expression patterns [16,23]. The isoforms from a plant species exhibited a very high sequence homology are consistence with gene duplication in polyploid genomes such as camelina experienced the whole genome triplication event. These isoforms also provide the targets for evolution selection to increase their functional divergence, which is suggested by their different expression patterns detected in various tissues/organs.

In eukaryotic cells, many genes can increase their functional diversity by alternative splicing [31,32]. For AtWRI1, three alternative splice forms were predicted, but only the WRI1 splice form 3 (At3g54320.3) transcript accumulated in multiple Arabidopsis tissues, including roots, flowers, developing seeds, and young seedlings [23]. RNAseq (RNA Sequencing) and EST (expressed sequence tag) data available for Brassica napus showed that the isoform corresponding to the WRI1 splice form 3 was only expressed in developing seeds [23]. In this study, two splice forms of RcWRI1 were cloned from castor bean, and their sequences were identical except for RcWRI1-A having a 9-bp fragment (TTTATTTGG) which is absent in RcWRI1-B (Figure 1). Unlike the three AtWRI1 splice forms, both splice forms of RcWRI1 were highly expressed in castor developing seeds (Figure 3). Moreover, RcWRI1-A, but not RcWRI1-B, is also expressed in the castor flower, leaf, and pericarp. The different expression patterns of these two RcWRI1 splice forms indicate that RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B may function in a tissue-specific manner although further studies are needed to characterize their functional divergence.

3.2. The Motif “VYL” Encoded by a 9-bp Exon Is an Important Component of WRI1 Proteins, But Not Necessary for Function of All WRI1s

Previous data showed that WRI1 proteins are conserved in regulating plant oil biosynthesis [16,21,25]. Moreover, The WRI1 orthologs and homologs show a high level of amino acid identity in the region spanning the two AP2 domains but with a high degree of divergence in the N-termini and C-termini [23,26]. The C-terminal WRI1 activation domain is crucial for transcriptional activation. However, the C-terminal region is very different in AtWRI1 and RcWRI1. In the first AP2 domain responsible for DNA-binding, a short motif “VYL” encoded by the 9-bp exon was conserved in AtWRI1 splice form 1 and 3, as well as other WRI1 orthologs from diverse plant species [33,34]. Of the 34 predicted AtWRI1-orthologous proteins at Phytozome, only two contained “IYL” instead of “VYL” [23]. Single amino acid mutation for each of “VYL” resulted in impairment of AtWRI1 function [23], indicating that “VYL” is an essential motif for function of AtWRI1. However, the “VYL” motif is missing in a number of WRI1 orthologs [23] although their functions have not been characterized yet. In the present study, the “VYL” is present in RcWRI1-A but absent in RcWRI1-B (Figure 1). Transient expressions of either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B in N. benthamiana leaves led to a significant increase of total FA content in the leaf tissue (Figure 7), suggesting that the lack of “VYL” do not affect the function of RcWRI1-B in promoting lipid biosynthesis and oil accumulation. Therefore, the “VYL” motif is not necessary for all WRI1 proteins.

3.3. Castor RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B Function to Increase Oil Biosynthesis in Heterogenous Tobacco Leaves by up Regulating the Target Genes Involved in Glycolysis and FA Synthesis

To meet the increasing demand for plant oils as foods and non-food uses, engineering high-biomass leaves for oil production is an alternative and promising strategy to increase the production of vegetable oils [1,35,36]. Transcriptional factor WRI1 is one of targets used in such approaches. For example, overexpression of AtWRI1 alone increased TAG content to 2.8-fold in Arabidopsis seedlings without obvious negative effects on plant development [36]. Similarly, ectopic expression of WRI1s from diverse species including potato, poplar, oat, nutsedge and camelina enhanced TAG levels by approximately 2–4-fold in N. benthamiana fresh leaves relative to the control leaves [21,26]. All these WRI1s function to induce oil accumulation in leaves via upregulating the genes encoding the enzymes required for FA biosynthesis, such as PKp-β1, ACP1, PDH-E1α, BCCP2, ACCase, SUS2, and KAS1 [21,26,36].

It was evident that ectopic expression of BdWRI1 isolated from a cereal plant Brachypodium distachyon induced an enhancement of TAG content in B. distachyon leaves, but simultaneously caused cell death in the leaf blades because of increased free FAs resulted from TAG turnover [25]. This negative phenotype by BdWRI1 overexpression in vegetative tissues was not observed for other WRI1s, indicating that the specific phenotypes caused by ectopic expression of WRI1 are dependent on species context although most of WRI1 overexpression experiments did not show negative effects.

Here, we transiently expressed castor RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B in N. benthamiana leaves. As expected, expressing either of these gene isoforms greatly upregulated the expressions of several WRI1 target genes, and subsequently resulted in a drastic increase of total FA content in the transformed leaf tissue. Furthermore, RcWRI1-B lacking the “VYL” motif displayed a much stronger activity than RcWRI1-A. Taken together, these data confirm that both RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B have a conserved function in regulating FA and TAG biosynthesis. Ectopic expression of RcWRI1s or other WRI1s can be a potential tool for increasing the energy density in vegetative organs of plants.

4. Materials and Method

4.1. Plant Materials

Castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) plants were grown in a greenhouse with 12/12 hr light/dark photoperiod at temperatures between 18 and 28 °C. Nicotiana benthamiana seedlings in a sterilized soil mixture (peat moss-enriched soil:vermiculite:perlite in 4:2:1 ratio) were grown in a growth chamber under fluorescent light (200 μmol∙m−2∙s−1) and with the following conditions: 16/8 h light/dark, 21/25 °C, and 50–60% humidity. Wild-type Arabidopsis thaliana and the wri1-1 mutant plants were grown in a growth chamber at 21/25 °C (day/night) with a 16 h light/8 h dark.

4.2. Castor Bean RcWRI1 Cloning

The RcWRI1 gene of castor bean (LOC8283400) was identified by searching the castor bean genomic database (Available online: http://castorbean.jcvi.org/index.php) using the BLAST algorithm and Arabidopsis AtWRI1 (At3g54320) sequence as query sequence. ORF of this gene was used to design a pair of primers to amplify RcWRI1 coding sequence. The primers used were RcWRI1-F1: 5′-ATGAAGAGGTCTCCTACTTC-3′ and RcWRI1-R1: 5′-TCAAACAGAATAGTTA CAAC-3′. Developing seeds (30 day after flowing, DAF, of castor bean were sampled to isolate total RNAs, which were then used for first-strand cDNA synthesis by PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The cDNAs were subsequently used for amplification of RcWRI1 ORF by RT-PCR using EasyPfu DNA Polymerase. Two amplicons different in length were cloned into pGEM T-easy vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and their nucleotide sequences were determined by sequencing. The long form (1341 bp) was designated as RcWRI1-A while the short form (1332 bp) was named RcWRI1-B.

4.3. Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

Multiple alignments of amino acid sequences of RcWRI1-A, RcWRI1-B and other plant WRI1s were performed with the ClustalW program (Available online: http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted by MEGA6 program with the Neighbor-joining algorithm method and a bootstrap value of 1000 replicates.

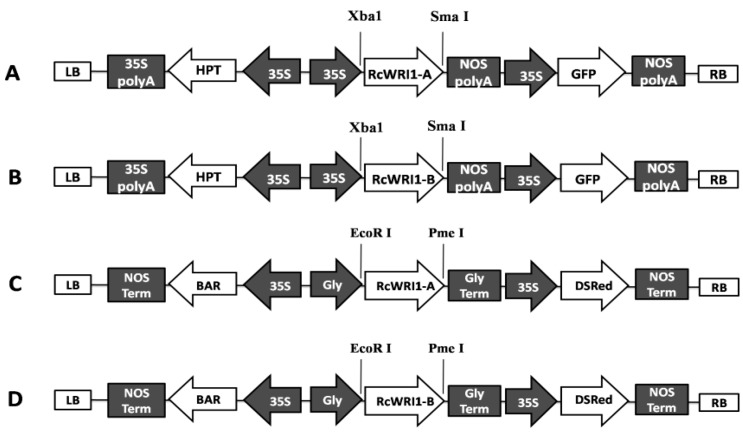

4.4. Vector Construction

The ORFs of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B were separately amplified from their corresponding clone vectors using gene-specific primers with Xbal (5′-end) and SmaI (3′-end) sites (RcWRI1-F2: 5′-GCTCTAGAATGAAGAGGTCTCCTACTTCC-3′ and RcWRI1-R2: 5′-TCCCCCGGGTCAAACA GAATAGTTACAAC-3′). RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B ORFs were then respectively inserted behind the CaMV 35S promoter in the pCAMBIA1303 vector (Figure 9). This vector contains a reporter gene GFP driven by the CaMV35S promoter, which facilitates the identification of transgenic events in transformation of Nicotiana benthamiana. For transformation of Arabidopsis, the ORFs of RcWRI1 were amplified from clone vectors using primers containing EcoRI and PmeI sites (RcWRI1-F3: 5′-CGGAATTCATGAAGAGGTCTCCTACTTCC-3′ and RcWRI1-R3: 5′-GGGTTTAAACTCAAA CAGAATAGTTACAAC-3′). RcWRI1s was then transferred into the pJC-Gly-DsRED binary vector under the control of the seed-specific Gly-promoter and with the DsRed selection marker. These vectors containing RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B were then transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 by the freeze-thaw method, which were used for Arabidopsis plant transformation.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of RcWRI1-A, and RcWRI1-B expression constructs used for transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and overexpression in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 mutant. (A) The RcWRI1-A expression cassette in pCAMBIA1303. (B) The RcWRI1-B expression cassette in pCAMBIA1303. (C) The RcWRI1-A expression cassette in pJC-Gly-DsRED. (D) The RcWRI1-B expression cassette in pJC-Gly-DsRED. 35S: CaMV 35S promoter. HPT: Hygromycin resistance gene. 35S polyA: 35S poly (A) signal sequence. Nos polyA: Nopaline synthase poly (A) signal sequence. Gly: Gly-promoter. BAR: Herbicide resistance bar gene. Gly term: Gly terminator. NOS term: Nopaline synthase terminator. GFP: Green fluorescent protein. RB: Right border. LR: Left border. DSRed: Discosoma red fluorescent protein.

4.5. Overexpressing RcWRI1s in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 Mutant

The expression vectors pJC-Gly-DSRED-RcWRI1s were introduced into the wri1-1 mutant through Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation by floral dipping [37]. Overnight culture of Agrobacterium was harvested by centrifugation, and then resuspended in infiltration medium with OD600 at 0.80 prior to use. The infiltration medium contained 5.0% sucrose and 0.05% Silwet L-77 (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Arabidopsis plants were inverted into the beaker of infiltration buffer and held vacuum for 10s in a vacuum chamber. After that, the plants were removed to a plastic tray and covered with a clear plastic for overnight in dark. Finally, the plants were returned to the growth chambers. The seeds were selected on MS (Murashige and Skoog) medium containing PPT (phosphinothricin) (10 mg/L) (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) and transferred to soil for further characterization. Homozygous plants were subsequently used in all experiments.

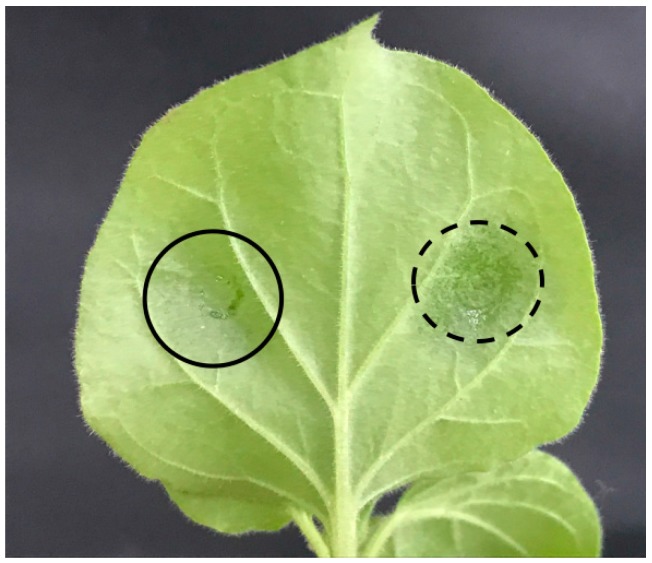

4.6. Transient Expression in Tobacco Leaves

Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 harboring the RcWRI1 gene expression vector was cultured overnight, and then resuspended in the buffer solution (100 μmol/L acetosyringone (Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), 10 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L MES (MES monohydrate) (PhytoTechnology, Shawnee Mission, KS, USA) to prepare the bacterium mixture with OD600 at 0.125 prior to infiltration. Tobacco (N. benthamiana) leaves of the 6-week-old plants were selected for agroinfiltration (Figure 10). One leaf per plant representing the same development stage was selected for infection. Six biological replicates were conducted for each expression vector. Three hundred microliters of the bacterium culture mixtures were infiltrated into the leaf, and plants were then incubated for six days in growth chambers with the same growth conditions as described above. The infiltrated leaf area showing GFP expression under UV-light were sampled, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C. The samples were used for RNA extraction (~200 mg FW (fresh weight)) and for lipid analyses (~800 mg FW). The empty-vector infected leaf areas were sampled as controls.

Figure 10.

Tobacco leaf image showing the regions infiltrated by the Agrobacterium. The left-half part of the leaf was infiltrated with Agrobacterium containing the RcWRI1 expression vector, while the right-half part of the leaf was infected by Agrobacterium containing an empty vector. The solid black circle shows the region infiltrated by the target gene, and dotted black circle marks the region infected by the empty-vector control.

4.7. Real-Time PCR to Examine Expression of RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B

Total RNA from castor flowers, leaves, pericarps, developing seeds (30 DAF) and tobacco leaves was extracted using Trizol Reagent (Shenggong BBI Life, Shanghai, China). One microgram of total RNA was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA by PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Dalian, China). qRT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara) on CFX 96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (BIO-RAD, Hercules, CA, USA), using a program with initial 95 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. Primers for qPCR are shown in Table 1. The 2−ΔΔCt calculation was used to determine the relative expression of downstream genes of WRI1, and two RcWRI1 expression levels in various castor organs calculated by 2−ΔCt [38].

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR in this study.

| Primer Name | Forward Primer Sequence (5′-3′) | Reverse Primer Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| NbActin | CAGTGGCCGTACAACAGGTA | AACCGAAGAATTGCATGAGG |

| NbPKp-β1 | CTGTGTCGCTACGGACTGAA | GTGTTGGACATCATCGTTGC |

| NbPKp-α | TAAAAGCTCGGGGCATGGTC | GGTTTCCCAGCTAAGAACTTGT |

| NbPDH-E1α | TGGTAACGATGCTCTTGCTG | CTCCACCATTCGATTTCGTT |

| NbACP1 | GCAAATGGATCGAGGCTAAC | CTTGGAAGGATCGACTTTGG |

| NbKAS1 | CACCCATCAATTCACCAATG | CCCATCCCAGTTATGACCAC |

| NbBCCP2 | GCTGATTCGTCTGGAACCAT | GCCTTCCACCTATGTTGCAT |

| RcActin | GTGCTTGATTCTGGTGATGGC | TTGGCAGTCTCAAGTTCTTGCTC |

| RcWRI1-A | GAAGGGAAGACAAGTTTATTTGG | ATTCAAGGTTGTCTCTGGTCC |

| RcWRI1-B | AAGGGAAGACAAGGGGCCTATG | GCTTTGGCGTCGAAGAGATG |

4.8. Lipid Analysis

To measure total fatty acid (FA) profile and content, total lipids extracted from leaf samples collected from N. benthamiana plants and Arabidopsis seeds. Tri 17:0-TAG in chloroform was added into sample as the internal control. Freeze-dried leaf and seed samples were ground into powder and 20 mg powder was used for total lipid extraction by following method described by Li et al. [39]. Briefly, the samples were homogenized in 1 mL chloroform and methanol (v:v = 2:1) containing 0.001% BHT, followed by adding 0.5 mL 0.9% (w/v) KCl solution and 1 mL chloroform, and then spinned for a few minutes for phase separation. The lower clear liquid phase was transferred into a clean glass tube, and the sample was dried by N2 flow. After that, 0.5 mL sodium methoxide was added into the tube for FA esterification, with shacking for 30 min. Finally, 0.5 mL isooctane was added into the esterified samples with well mixture. The upper layer containing the FA methyl esters (FAME) was transferred into GC auto-sampler vials. The samples were measured by gas chromatography (Agilent 7890B, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm FFAP(free fatty acid phase) column, flame ionization detector, (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA)). The peak area for each FA on the retention time was characterized and measured by comparison with the known standard FA profiles, and the concentration of each FA was calculated by comparing its peak area with that of the internal standard.

5. Conclusions

The RcWRI1 gene in castor expressed two alternative spliced forms, RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B. These two splice forms exhibited tissue-specific expression patterns in castor. Expression of either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B could rescue the low oil content in the Arabidopsis wri1-1 seeds. Transient expression of either RcWRI1-A or RcWRI1-B in N. benthamiana leaves significantly upregulated the expressions of the target genes such as PKp-β1, ACP1, and KAS1, and greatly increased total FA levels in the leaves, indicating that both gene isoforms function in regulation of FA biosynthesis and TAG accumulation. The conserved “VYL” motif is not necessary for function of all WRI1 proteins including RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B although it is essential for Arabidopsis AtWRI1 function. The present findings demonstrate that RcWRI1-A and RcWRI1-B can be employed as master transcriptional factors to engineer high-biomass plants for increasing commercial production of vegetable oils.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31401430), National “948” Program (Grant No. 2014-Z39), the Coal-based Key Sci-Tech Project of Shanxi Province (Grant No. FT-2014-01), the Key Project of The Key Research and Development Program of Shanxi Province, China (Grant No. 201603D312005), and Research Project Supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (2015-064).

Abbreviations

| TAGs | triacylglycerols |

| ORF | open reading frame |

| PKp-β1 | plastid pyruvate kinase beta subunit 1 |

| PDH-E1α | dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit |

| BCCP2 | biotin carboxyl carrier protein isoform 2 |

| ACCase | acetyl-CoA carboxylase |

| SUS2 | sucrose synthase 2 |

| KAS1 | 3-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase 1 |

| Pyr | pyruvate |

| CoA | acetyl-coenzyme A |

| ER | endoplasmic reticulum |

| G3P | glycerol-3-phosphate |

| DAF | days after florescence |

| FFAP | free fatty acid phase |

| FAME | FA methyl esters |

| MS | Murashige and Skoog |

| PPT | phosphinothricin |

| MES | MES monohydrate |

| FW | fresh weigh |

| EST | expressed sequence tag |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/1/146/s1.

Author contributions

The design of the study was made by Run-Zhi Li; sequence alignments and molecular cloning of genes were performed by Xia-Jie Ji, Xue Mao and Qing-Ting Hao; statistical analysis was carried out by Bao-Ling Liu and Jin-Ai Xue; Xia-Jie Ji drafted the manuscript with help from Run-Zhi Li. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Vanhercke T., El Tahchy A., Liu Q., Zhou X.R., Shrestha P., Divi U.K., Ral J.P., Mansour M.P., Nichols P.D., James C.N., et al. Metabolic engineering of biomass for high energy density: Oilseed-like triacylglycerol yields from plant leaves. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014;12:231–239. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durrett T.P., Benning C., Ohlrogge J. Plant triacylglycerols as feedstocks for the production of biofuels. Plant J. 2008;54:593–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu C., Napier J.A., Clemente T.E., Cahoon E.B. New frontiers in oilseed biotechnology: Meeting the global demand for vegetable oils for food, feed, biofuel, and industrial applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2011;22:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baud S., Lepiniec L. Physiological and developmental regulation of seed oil production. Prog. Lipid Res. 2010;49:235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li-Beisson Y., Shorrosh B., Beisson F., Andersson M.X., Arondel V., Bates P.D., Baud S., Bird D., Debono A., Durrett T.P., et al. Acyl-lipid metabolism. Arab. Book. 2013;11:e0161. doi: 10.1199/tab.0161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bates P.D., Stymne S., Ohlrogge J. Biochemical pathways in seed oil synthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2013;16:358–364. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y., Li R., Hildebrand D.F. Biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of palmitoleate production, an important contributor to human health and sustainable industry. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012;51:340–349. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y., Xue X., Chang M., Gao Y., Zhang L., Xue J.A., Run-Zhi L.I. New type of industrial oilseed crop Camelina Sativa: From genome to metabolic engineering. Plant Physiol. J. 2015;51:1204–1216. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weselake R.J., Taylor D.C., Rahman M.H., Shah S., Laroche A., McVetty P.B., Harwood J.L. Increasing the flow of carbon into seed oil. Biotechnol. Adv. 2009;27:866–878. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Napier J.A. The production of unusual fatty acids in transgenic plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2007;58:295–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bates P.D., Durrett T.P., Ohlrogge J.B., Pollard M. Analysis of acyl fluxes through multiple pathways of triacylglycerol synthesis in developing soybean embryos. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:55–72. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.137737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cernac A., Benning C. Wrinkled1 Encodes an AP2/EREB domain protein involved in the control of storage compound biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2004;40:575–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Focks N., Benning C. Wrinkled1: A novel, low-seed-oil mutant of arabidopsis with a deficiency in the seed-specific regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:91–101. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baud S., Bourrellier A.B.F., Azzopardi M., Berger A., Dechorgnat J., Daniel-Vedele F., Lepiniec L., Miquel M., Rochat C., Hodges M., et al. Pii Is Induced by wrinkled1 and fine-tunes fatty acid composition in seeds of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2010;64:291–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adhikari N.D., Bates P.D., Browse J. Wrinkled1 Rescues Feedback inhibition of fatty acid synthesis in hydroxylase-expressing seeds. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:179–191. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.To A., Joubes J., Barthole G., Lecureuil A., Scagnelli A., Jasinski S., Lepiniec L., Baud S. Wrinkled transcription factors orchestrate tissue-specific regulation of fatty acid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:5007–5023. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Q.T., Lu X., Song Q.X., Chen H.W., Wei W., Tao J.J., Bian X.H., Shen M., Ma B., Zhang W.K., et al. Selection for a zinc-finger protein contributes to seed oil increase during soybean domestication. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:2208–2224. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maeo K., Tokuda T., Ayame A., Mitsui N., Kawai T., Tsukagoshi H., Ishiguro S., Nakamura K. An AP2-type transcription factor, wrinkled1, of arabidopsis thaliana binds to the aw-box sequence conserved among proximal upstream regions of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis. Plant J. 2009;60:476–487. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J., Hua W., Zhan G., Wei F., Wang X., Liu G., Wang H. Increasing seed mass and oil content in transgenic arabidopsis by the overexpression of Wri1-Like gene from Brassica napus. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010;48:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen B., Allen W.B., Zheng P., Li C., Glassman K., Ranch J., Nubel D., Tarczynski M.C. Expression of Zmlec1 and Zmwri1 Increases seed oil production in Maize. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:980–987. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dahee A., Kim H., Ju S., Go Y.S., Kim H.U., Suh M.C. Expression of Camelina wrinkled1 isoforms rescue the seed phenotype of the Arabidopsis Wri1 mutant and increase the triacylglycerol content in tobacco leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:34. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourgis F., Kilaru A., Cao X., Ngando-Ebongue G.F., Drira N., Ohlrogge J.B., Arondel V. Comparative Transcriptome and metabolite analysis of oil palm and date palm mesocarp that differ dramatically in carbon partitioning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:12527–12532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106502108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma W., Kong Q., Arondel V., Kilaru A., Bates P.D., Thrower N.A., Benning C., Ohlrogge J.B. Wrinkled1, a ubiquitous regulator in oil accumulating tissues from Arabidopsis embryos to oil palm mesocarp. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e68887. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjodin A., Street N.R., Sandberg G., Gustafsson P., Jansson S. The populus genome integrative explorer (popgenie): A new resource for exploring the populus genome. New Phytol. 2009;182:1013–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y., Munz J., Cass C., Zienkiewicz A., Kong Q., Ma W., Sanjaya Sedbrook J., Benning C. Ectopic expression of Wrinkled1 affects fatty acid homeostasis in Brachypodium distachyon vegetative tissues. Plant Physiol. 2015;169:1836–1847. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grimberg A., Carlsson A.S., Marttila S., Bhalerao R., Hofvander P. Transcriptional transitions in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves upon induction of oil synthesis by WRINKLED1 homologs from diverse species and tissues. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:192. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0579-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akande T.O., Odunsi A.A., Akinfala E.O. A review of nutritional and toxicological implications of Castor Bean (Ricinus Communis L.) meal in animal feeding systems. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2016;100:201–210. doi: 10.1111/jpn.12360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scarpa A., Guerci A. Various uses of the castor oil plant (Ricinus communis L.). A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1982;5:117–137. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(82)90038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y., Liu L., Tian X., Di J., Su Y., Huang F., Chen Y. Crucial enzymes in the hydroxylated triacylglycerol-ricinoleate biosynthesis pathway of castor bean. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2014;15:572–582. doi: 10.2174/1389203715666140724085543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ast G. How did alternative splicing evolve? Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:773–782. doi: 10.1038/nrg1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filichkin S.A., Priest H.D., Givan S.A., Shen R., Bryant D.W., Fox S.E., Wong W.K., Mockler T.C. Genome-wide mapping of alternative splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 2010;20:45–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.093302.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo P.J., Park M.J., Lim M.H., Kim S.G., Lee M., Baldwin I.T., Park C.M. A self-regulatory circuit of circadian clock-associated1 underlies the circadian clock regulation of temperature responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2427–2442. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.098723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okamuro J.K., Caster B., Villarroel R., van Montagu M., Jofuku K.D. The AP2 Domain of APETALA2 defines a large new family of DNA binding proteins in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7076–7081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riechmann J.L., Meyerowitz E.M. The AP2/EREBP family of plant transcription factors. Biol. Chem. 1998;379:633–646. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim H.U., Lee K.R., Jung S.J., Shin H.A., Go Y.S., Suh M.C., Kim J.B. Senescence-inducible LEC2 enhances triacylglycerol accumulation in leaves without negatively affecting plant growth. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:1346–1359. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanjaya T., Durrett P., Weise S.E., Benning C. Increasing the energy density of vegetative tissues by diverting carbon from starch to oil biosynthesis in Transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2011;9:874–883. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2011.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clough S.J., Bent A.F. Floral dip: A simplified method for agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li R., Yu K., Wu Y., Tateno M., Hatanaka T., Hildebrand D.F. Vernonia DGATs can complement the disrupted oil and protein metabolism in epoxygenase-expressing soybean seeds. Metab. Eng. 2012;14:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.