Abstract

Type 1 Diabetes is associated with such complications as blindness, kidney failure, and nerve damage. Replacing C-peptide, a hormone normally co-secreted with insulin, has been shown to reduce diabetes-related complications. Interestingly, after nearly 30 years of positive research results, C-peptide is still not being co-administered with insulin to diabetic patients. The following review discusses the potential of C-peptide as an auxilliary replacement therapy and why it's not currently being used as a therapeutic.

Introduction

Type 1 Diabetes and Insulin

Depending on the source, there are currently ∼ 400 million cases of diagnosed diabetes worldwide. If approximately 7-10% of these cases are assumed to be cases of type 1 diabetes (T1D), one could conservatively surmise that more than 25 million people currently have T1D.1, 2 People living with T1D must administer insulin because their pancreatic β-cells, the cells responsible for the production of insulin and other molecules in vivo, are destroyed resulting in little or no insulin production. Due to work by many groups in the early part of the last century,3 the use of insulin has extended the life expectancy of people living with T1D. In fact, insulin administration coupled with proper diet and activity has resulted in the difference in life expectancy between diabetics and age-matched non-diabetics being 13 years in 2015, down from 27 years in a report from 1975.4 However, despite these improvements in life expectancy, people with T1D still endure many health complications, thus triggering many studies involving the “other” molecules secreted by healthy pancreatic β-cells..5-7 A retrospective study of the large scale Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed significant correlation between decreased T1D complications and residual β-cell secretions even when patients controlled their blood glucose levels to that of non-diabetics.8 Thus leading researchers to believe that conventional therapies, such as diet and exercise, are not sufficient to eliminate diabetic complications, and that new treatments are necessary. As covered in previous review articles, researchers have shown that C-peptide administration may improve the chronic morbid conditions that T1D patients suffer from, such as neuropathy, retinopathy, nephropathy, and more, through a vast range of hypothesized etiologies.5-12 However, the focus of this review is the current state of C-peptide research and to provide direction to progress the use of therapeutic C-peptide

C-peptide's Discovery, Emergence as a Biologically Active Substance, and Dampened Enthusiasm

In 1967, C-peptide was discovered as part of the proinsulin molecule.13 This 31-amino acid segment of the proinsulin hormone remained intact after cleavage from insulin and, importantly, was found to be secreted in equimolar amounts with insulin from the pancreatic β-cell granules.14 Ensuing studies over the next two decades suggested that C-peptide did not exert any significant biological effects in vivo.15 However, due to its ∼30 minute half-life in the circulation, the development of a C-peptide radioimmunoassay proved invaluable for quantitative determinations involving insulin production in vivo (insulin's half-life in the bloodstream is ∼ 4 minutes), thereby becoming a very powerful biomarker for residual β-cell activity.16, 17

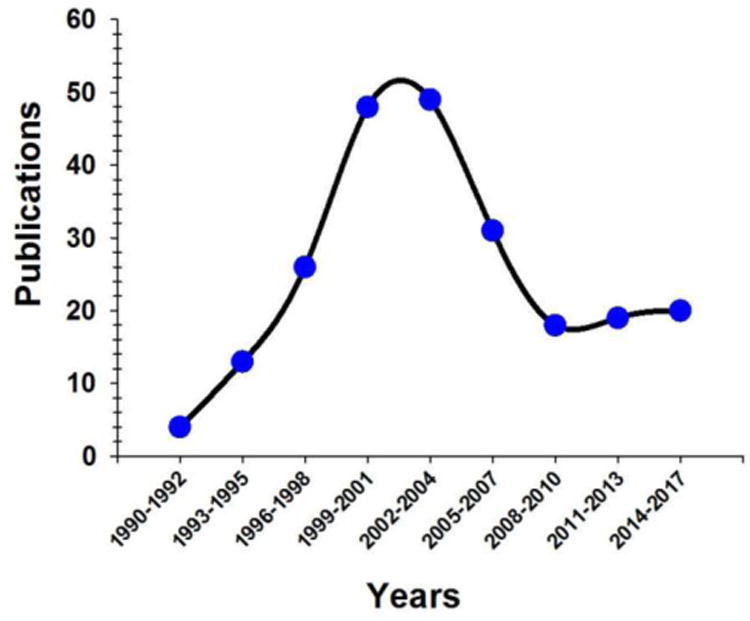

During the time between the discovery of C-peptide and the early 1990's, it was noted that people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) who had some residual β-cell activity (as measured by plasma C-peptide levels) often suffered less complications than those people with T1D and no residual activity.18 These observations may have, in part, led to a resurgence of C-peptide publications in the literature beginning in the early 1990's (Fig.1). Between 1990 and the peak years of C-peptide publications (up to 2001), there were 136 publications involving C-peptide, peaking in 2001 with 22 peer-reviewed published articles. As shown in Fig. 1, that number has steadily declined since 2001, with only 14 articles published since 2014. Furthermore, one of the major obstacles to C-peptide's candidacy as an active biological molecule, specifically, the identification of a receptor, is still lacking despite efforts and progress by multiple groups.19-21 Finally, a recent effort to bring a C-peptide based therapy to market stalled in phase IIb clinical trials.22 Cebix, a start-up company based in California, backed by investments of over $50 million (US) brought forth Ersatta, a once-weekly injected therapy with indications for improving neuropathy. Ersatta was successful in early phase studies, although results from phase IIb trials involving people with T1D found no improvement relative to patients receiving placebo.

Figure 1.

A graphical depiction of the number of research papers and meeting abstracts published between 1990 and March, 2017 involving C-peptide and its role as an active biological substance. This data was obtained using Thomson-Reuters Web of Science.

An evaluation of recent publication activity, coupled with stalled clinical trials, and lack of an identified receptor begs the question if this “second round” of C-peptide research (relative to initial rounds soon after its discovery) provides definitive proof that C-peptide is not a biologically active substance, save for participating in the folding of insulin. On the other hand, a reappraisal of the data in Fig. 1 suggests that C-peptide is following the path of many products and technologies in the form of a classic “hype curve.”

Are C-peptide Studies in the Trough of Disillusionment of a Typical Technology Hype Curve?

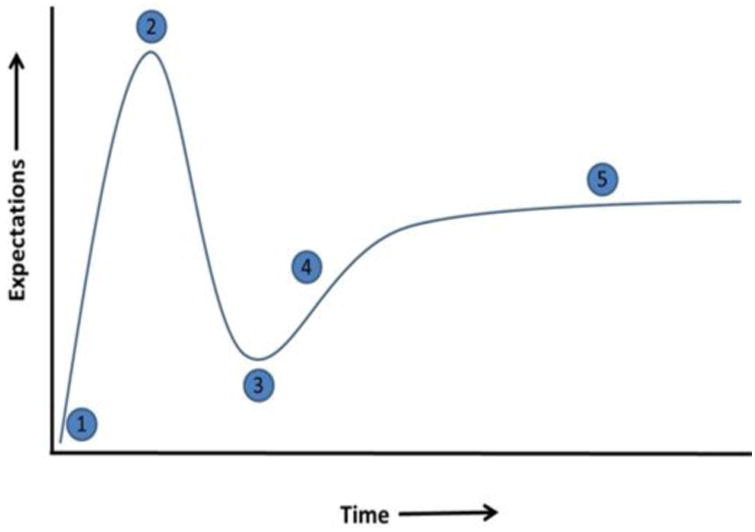

A hype curve, more widely known as a hype cycle (although this label is criticized because there is no “cycle” in the illustrations), is a graphical representation of the maturity of an emerging technology. An excellent explanation of the hype curve can be found in Amara's law, which states that “we tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run”. A typical hype curve is often represented as moving through 5 phases, as shown in Fig. 2.23 The first phase is the technology trigger, where a potential new technology sets off new early-stage proof of concept studies, followed by media-induced publicity. The publicity reports a number of successes, enabling the technology to reach stage 2, the peak of inflated expectations. Eventually, the excitement over the technology diminishes due to failed expectations and experiments, and followers of the technology during the rise between points 1 and 2 begin to bail out or give up on the technology. This third stage is often called the trough of disillusionment. After reaching a minimum, there is a slope of enlightenment period (stage 4), where a re-appraisal of the technology demonstrates potential utility; importantly, during this phase, 2nd and 3rd generation versions of the technology are presented by producers/investigators. An improved understanding of the technology is obtained. Finally, in stage 5, mainstream adaptation of the technology emerges and the product relevance begins to see public acceptance and clear, trusted providers of the technology. It should be noted that there are many criticisms of technology hype curves. A major critique of hype curves that is compelling to the authors is that most curves offer no action plan to rise from the trough of disillusionment, thereby providing no strategy for moving a technology to the next phase. In response to this perceived shortcoming of hype curves, we provide our own input for positioning C-peptide as an auxiliary therapy for people with T1D. Specifically, we focus on standardization of C-peptide purification and characterization methods, standardized formulation of C-peptide, and a need for improved non-human models of T1D.

Figure 2.

A graphical representation of the typical “hype cycle” by Gartner Research Methodologies, showing the maturity phases of a new technology. Each phase is described as follows: (1) Innovation Trigger, (2) Peak of Inflated Expectations, (3) Trough of Disillusionment, (4) Slope of Enlightenment, (5) Plateau of Productivity.

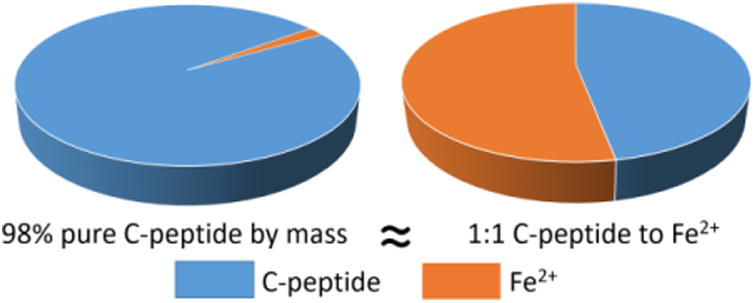

C-peptide Purity and Characterization

An evaluation of the literature will demonstrate that not all C-peptide is created, nor prepared, in the same manner prior to use for in vitro or in vivo settings. In the literature, C-peptide purity has been reported to be 95%, 98%, 100% and many times, unreported; most of the time, the purity reported is that provided by the manufacturer of the C-peptide and not the lab using the C-peptide for experiments. Importantly, we believe that most users of C-peptide are underestimating the importance of even a 2% impurity. Consider a 1 mg sample of C-peptide reported to have a purity of 98%; that percent purity is based on mass. In other words, a 1 mg sample of C-peptide at 98% purity actually contains 0.98 mg of C-peptide and 0.02 mg of something else. Previously, we have shown that the “something else” is divalent iron, Fe2+.24 Therefore, by mass, the 1 mg sample contains 0.98 mg of C-peptide and 0.02 mg of iron, a level of which seems inconsequential. However, binding events and reactions at the molecular level (e.g., C-peptide binding to a cell) are based on moles and hence, the number of molecules. In the case of 98% C-peptide, a calculation shows that 0.98 mg (or 0.00098 g) contains about 320 nanomoles of C-peptide. In that same 98% pure sample, there are also 0.02 mg (or 0.00002 g), or about 360 nanomolesof Fe2+. In other words, a sample of C-peptide at 98% purity actually is contaminated in almost a 1:1 ratio with Fe2+ (Fig. 3). A 95% pure sample would most likely contain even more impurities and, if a metal like Fe2+, would make the ratio of contaminating species even higher.

Figure 3.

A graphical depiction of the purity of purchased C-peptide as analysed by mass spectrometry. A sample containing 98% pure C-peptide by mass was found to be bound to Fe2+ in a 1:1 mole ratio. This Fe2+ adduct can be removed by high performance liquid chromatography.

The above discussion on purity is not meant to suggest that certain experiments fail or succeed because of Fe2+, or even that purity of C-peptide itself is a determinant in success or failure; rather, the discussion is meant to make users of C-peptide aware that starting materials are obviously important and that greater care in standardization methods of the starting materials need to be considered. As a small example, one only needs to look at the number of reports in the literature identifying the importance of metals associated with C-peptide.25,26 Interestingly, others have reported significantly reduced, or almost no biological activity, when C-peptide is in the presence of EDTA, a very strong zinc chelator that has the binding affinity to remove zinc from C-peptide and other zinc binding proteins such as albumin.27 Moving forward, we suggest that all commercially or in-house synthesized C-peptide should be re-purified by HPLC and then characterized by mass spectrometry to ensure that the purity is as close to 100% as possible. The importance of knowing the exact starting material is described below in more detail.

Formulation of C-peptide

In addition to characterization of C-peptide purity prior to experimentation, it may be that C-peptide's biological effects are not due to C-peptide alone. For example, in our laboratory, we do not see any biological effects from C-peptide on erythrocytes unless albumin is present in the buffer.28 In fact, we do not see any binding of C-peptide to the cells unless albumin is present. An evaluation of the literature will show that most reports involving C-peptide efficacy have either albumin directly added to the buffer, or in cell culture media (typically as added fetal bovine serum), or is present naturally (if an in vivo system). Interestingly, there are many indicators that C-peptide may indeed be carried in the bloodstream, and delivered to cells, by albumin. First, the half-life of C-peptide in the bloodstream plasma is in excess of 30 minutes, suggesting that it is being carried by or bound to a plasma protein.29 Indeed, prior to our initial report of albumin carrying C-peptide, Steiner hypothesized that C-peptide was possibly being carried by a bloodstream protein in vivo.29 In continuance, albumin is often known to carry more acidic proteins and peptides; C-peptide is a very acidic peptide, possessing six carboxylic acid-containing amino acids in the form of glutamic and aspartic acids. Accordingly, our group has shown that substitution of the glutamic acid residue at position 27 results in no binding to albumin.28 Such results coincide with numerous early reports by many groups demonstrating loss of C-peptide biological activity when this residue was substituted.30-32

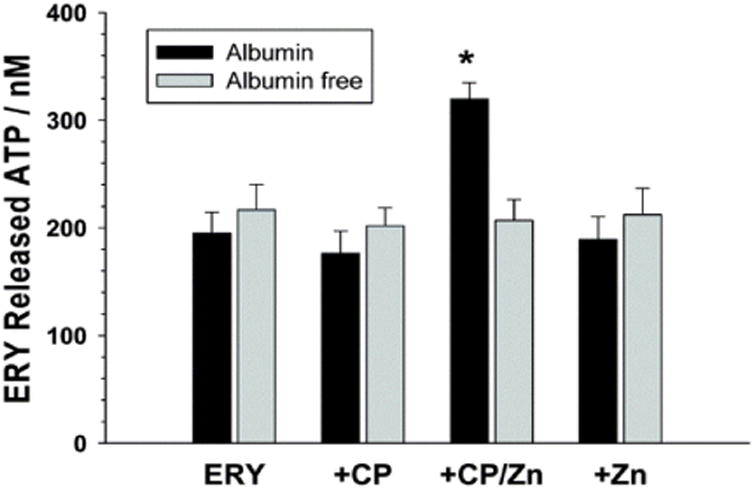

As mentioned earlier, in addition to C-peptide delivery to cells by albumin, there may be other additives needed for cellular effects. Specifically, while our group has reported binding of C-peptide to erythrocytes in the presence of albumin, we were not able to measure any enhancements to cell metabolism or cellular membrane properties unless the albumin and C-peptide were in the presence of zinc (Fig. 4).28 Not unlike our albumin findings, there is evidence in the literature that zinc is a determinant in the overall activity of C-peptide. In a recent murine-model study, the addition of zinc to a C-peptide formulation reduced complications from sepsis.26 Others have reported a significant decrease in C-peptide effects in the presence of EDTA; the authors of this study suggested that EDTA was probably binding calcium stores inside of the effected cells, therefore affecting Ca2+ dependant Na+, K+, ATPase.27 However, this is highly unlikely as EDTA would be in a charged state at physiological pH and would likely not cross a cell membrane and bind intracellular calcium stores. A more likely scenario is that EDTA was binding any available metal that would result in C-peptide activity (such as zinc or iron impurities in the initial C-peptide sample, again emphasizing the importance of characterizing C-peptide purity prior to experimentation).

Figure 4.

The ability of C-peptide (CP) to increase the ATP released from erythrocytes (ERY) was evaluated in vitro with a 3D-printed fluidic device.21 The cells only responded to C-peptide when in the presence of Zn2+ and albumin. The cells treated with C-peptide alone showed no response.

Collectively, we believe that C-peptide binding to cells does not occur unless in the presence of albumin and, even when binding does occur, cellular metabolic pathways are not significantly initiated unless zinc is also delivered to the cell with albumin and C-peptide. We have demonstrated that in the absence of any one of these three species, no cellular effects are measured in our in vitro systems. It should be noted that decades of successful research involving C-peptide has been reported without addition of albumin or zinc; however, in most cases, albumin is present either in cell culture media or endogenously in plasma (for in vivo studies). As mentioned already, metals such as iron or zinc may have been present as impurities during C-peptide preparation or added as an impurity when co-administered with insulin. However, all of these successful C-peptide studies, whether performed with albumin or zinc or not, still do not explain past success with C-peptide replacement therapy in animals, yet clinical failures with diabetic humans. Therefore, a discussion of animal vs. diabetic models is needed.

T1D Models for Investigating C-peptide Replacement Therapy

The T1D animal model is often used as a mimic of human diabetes to evaluate mechanism(s) of disease and potential therapy treatments. The most commonly used model is the streptozotocin (STZ) rodent model, where a rodent, typically a rat or mouse, is given either a large dose or several small doses of STZ, which has a cytotoxic effect on the pancreatic β-cells.33, 34 Traditionally, almost immediately following treatment with STZ, the rodents are regularly administered insulin for survival. The rodents regularly gain weight as a consequence of becoming hyperglycemic and are commonly very ill and under immense health-stress.35 The rodentsrapidly develop symptoms that mimic diabetic neuropathy, such as decreased sensory nerve conduction velocity, decreased sciatic nerve substance, and latency in response to pain and thermal stimuli.35-37 Though these symptoms imitate diabetic neuropathy as seen in humans, researchers have been skeptical of whether these symptoms are genuinely indicative of diabetic neuropathy as seen in humans, or rather attributed to the extreme ill health of the rodents.35

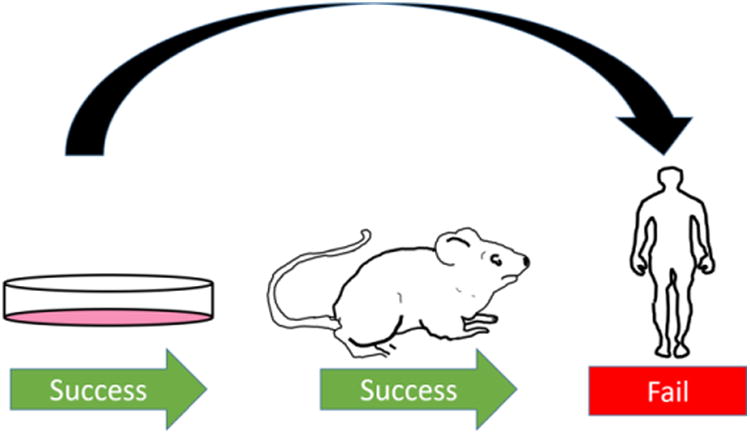

C-peptide replacement therapy has been studied in several diabetic animal models including the STZ rat, STZ mouse, and the BB/Wor rat. In all of these models, C-peptide has repeatedly shown promising beneficial effects against the development of neuropathy, retinopathy, and nephropathy. Unfortunately, results involving C-peptide replacement therapy in the T1D animal model do not parallel replacement therapy in T1D human adults (Fig. 5). For instance, typically a rodent is treated with insulin and/or c-peptide within several days of becoming hyperglycemic from being induced with diabetes. Therefore, the rodent has spent very little time experiencing deficiencies in pancreatic secretions. In contrast, an adult human who has been diabetic for years may enter a clinical study without C-peptide in their bloodstream for decades. During these years spent as a diabetic (and in the absence of C-peptide), the adult human experiences consistent hyperglycemia. This high-concentration of glucose in the bloodstream interacts with proteins in a slow, time-dependant manner, causing protein-glycation and the formation of advanced-glycation end-products.38-40 Proteins impacted by glycation in diabetes are known to have altered or damaged properties,41, 42 and advanced glycation end-products are hypothesized to be a cause of diabetes complications.43 Importantly, the rate of glycation takes place on the order of months, and the downstream effects could hypothetically increase over the course of years during hyperglycemia. Therefore, prior to receiving C-peptide in a clinical study, the diabetic-animal does not experience the same hyperglycemic time-period as the adult human. Consequently, the authors question the validity of the diabetic rodent to be an accurate representation of diabetes in humans due to this difference in hyperglycemic time-scale, and this may be the cause of contradictory results observed between human and diabetic-animal model studies of C-peptide replacement and other diabetes drugs.44

Figure 5.

The relevance of the diabetic-animal model has been questioned throughout the literature. The authors suggest implementing more rigorous in vitro studies and skipping the questionable animal models.

C-peptide proved to be effective in improving motor nerve conduction velocity (MNCV), a common metric of nerve damage in diabetes, in both the STZ and BB/Wor rat.45, 46 However, in a study titled “Amelioration of Sensory Nerve Dysfunction by C-Peptide in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes” the authors report no improvement in MNCV in humans following 12 weeks of C-peptide treatment.12 Similarly, in 2015 it was published that a PEGylated C-peptideanalogue (Peg-C-peptide) was able to significantly prevent losses in sensory nerve conduction velocity, paw thermal response latency, and other indices of peripheral neuropathy in STZ mice.37 However, in 2016 it was published that a large-scale 12-month human trial of Peg-C-peptide showed no improvement in sural sensory nerve conduction velocity in Type 1 Diabetic patients when compared to placebo.22

Clearly, there are stark inconstancies between the diabetic-animal model and the diabetic human, and these inconsistencies have repeatedly caused misperceptions in the efficacy of diabetic treatments. This is a problem of major concern because of the large amount of time and millions of dollars wasted on promising drug candidates. However, thorough drug testing prior to human trials is a necessity. The authors recommend a focus be placed on more rigorous in vitro studies containing conditions that more accurately mimic the diabetic human. Technologies involving organ-on-chip and human-on-chip models are rapidly improving to mimic in vivo conditions so that drug candidates can be tested under appropriate human-like conditions.28, 47-50

Conclusions

This year marks the 50th anniversary year since the initial publication from Steiner reporting the discovery of C-peptide. There have been hundreds of publications describing the health benefits of C-peptide ranging from in vitro studies involving cultured cells to in vivo human clinical trials. The successes of the experiments performed over the past 25 years by multiple research groups strongly suggests that C-peptide does have potential as an auxiliary therapeutic with insulin, especially due to its ability to improve blood flow. Furthermore, the half-life of C-peptide in the bloodstream also suggests that its role may be complimentary to insulin, working primarily in the circulation as opposed to tissues outside of the bloodstream. In any case, in this review, the main goal of the authors was to provide a brief overview of the current state of C-peptide research and possible directions moving forward for successful use of C-peptide by people with T1D. Of course, a therapy means a successful clinical trial, which will require a tremendous investment of resources, especially financial.

Acknowledgments

The authors recognize the National Institutes of Health (GM110406 and DK019986) and The Hunt for a Cure Foundation for financial support.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Notes and references

- 1.International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Global Report on Diabetes. World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banting F, Campbell W, Fletcher A. British medical journal. 1923;1:8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.3236.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Livingstone SJ, Levin D, Looker HC, Lindsay RS, Wild SH, Joss N, Leese G, Leslie P, McCrimmon RJ, Metcalfe W. Jama. 2015;313:37–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sima AA. Diabetes & C-peptide: Scientific and Clinical Aspects. Springer Science & Business Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wahren J. Clinical physiology and functional imaging. 2004;24:180–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2004.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahren J, Ekberg K, Johansson J, Henriksson M, Pramanik A, Johansson BL, Rigler R, Jörnvall H. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology And Metabolism. 2000;278:E759–E768. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.5.E759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lachin JM, McGee P, Palmer JP. Diabetes. 2013 doi: 10.2337/db13-0881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahren J. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2017;281:3–6. doi: 10.1111/joim.12541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pujia A, Gazzaruso C, Montalcini T. Endocrine. 2017:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12020-017-1286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yosten GL, Kolar GR. Physiology. 2015;30:327–332. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00008.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekberg K, Brismar T, Johansson BL, Jonsson B, Lindström P, Wahren J. Diabetes. 2003;52:536–541. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.2.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steiner DF, Cunningham D, Spigelman L, Aten B. Science. 1967;157:697–700. doi: 10.1126/science.157.3789.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubenstein AH, Clark JL, Melani F, Steiner DF. Nature. 1969;224:697–699. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoogwerf BJ, Bantle JP, Gaenslen HE, Greenberg BZ, Senske BJ, Francis R, Goetz FC. Metabolism. 1986;35:122–125. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth J, Whitford I, Dankner R, Szulc A. Diabetologia. 2012;55:865–869. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heding LG. Radioimmunoassays for Insulin, C-Peptide and Proinsulin. Springer; 1988. pp. 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sjöberg S, Gunnarsson R, Gjötterberg M, Lefvert A, Persson A, Östman J. Diabetologia. 1987;30:208–213. doi: 10.1007/BF00270417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards JP, Yosten GL, Kolar GR, Jones CW, Stephenson AH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2014;307:R862–R868. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00206.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yosten GL, Kolar GR, Redlinger LJ, Samson WK. Journal of Endocrinology. 2013;218:B1–B8. doi: 10.1530/JOE-13-0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luzi L, Zerbini G, Caumo A. Diabetologia. 2007;50:500–502. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0576-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wahren J, Foyt H, Daniels M, Arezzo JC. Diabetes care. 2016;39:596–602. doi: 10.2337/dc15-2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fenn J, Raskino M. Mastering the hype cycle: how to choose the right innovation at the right time. Harvard Business Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meyer J. Successful and reproducible bioactivity with C-peptide via activation with zinc. Michigan State University; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer JA, Froelich JM, Reid GE, Karunarathne WK, Spence DM. Diabetologia. 2008;51:175–182. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0853-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slinko S, Piraino G, Hake PW, Ledford JR, O'Connor M, Lahni P, Solan PD, Wong HR, Zingarelli B. Shock (Augusta, Ga) 2014;41:292. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hach T, Forst T, Kunt T, Ekberg K, Pfützner A, Wahren J. Experimental Diabetes Research. 2008;2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/730594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Chen C, Summers S, Medawala W, Spence DM. Integrative Biology. 2015;7:534–543. doi: 10.1039/c4ib00243a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steiner DF. In: Diabetes and C-peptide Scientific and Clinical Aspects. Sima AA, editor. Humana Press; 2012. pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pramanik A, Ekberg K, Zhong Z, Shafqat J, Henriksson M, Jansson O, Tibell A, Tally M, Wahren J, Jörnvall H. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2001;284:94–98. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keltner Z, Meyer JA, Johnson EM, Palumbo AM, Spence DM, Reid GE. Analyst. 2010;135:278–288. doi: 10.1039/b917600d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriksson M, Nordling E, Melles E, Shafqat J, Ståhlberg M, Ekberg K, Persson B, Bergman T, Wahren J, Johansson J. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2005;62:1772–1778. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Junod A, Lambert A, Orci L, Pictet R, Gonet A, Renold A. Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 1967;126:201–205. doi: 10.3181/00379727-126-32401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tesch GH, Allen TJ. Nephrology. 2007;12:261–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fox A, Eastwood C, Gentry C, Manning D, Urban L. Pain. 1999;81:307–316. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00024-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Apfel SC. Drug Discovery Today: Disease Models. 2007;3:397–402. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jolivalt C, Rodriguez M, Wahren J, Calcutt N. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2015;17:781–788. doi: 10.1111/dom.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barnaby OS, Cerny RL, Clarke W, Hage DS. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barnaby OS, Cerny RL, Clarke W, Hage DS. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2011;412:1606–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anguizola J, Matsuda R, Barnaby OS, Hoy KS, Wa C, DeBolt E, Koke M, Hage DS. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2013;425:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rondeau P, Bourdon E. Biochimie. 2011;93:645–658. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baraka-Vidot J, Guerin-Dubourg A, Bourdon E, Rondeau P. Biochimie. 2012;94:1960–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartog JW, Voors AA, Bakker SJ, Smit AJ, Veldhuisen DJ. European journal of heart failure. 2007;9:1146–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yorek MA. In: International Review of Neurobiology. Nigel AC, Paul F, editors. Vol. 127. Academic Press; 2016. pp. 89–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cotter MA, Cameron NE. Diabetes. 2001;50:A184. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sima AAF, Zhang W, Sugimoto K, Henry D, Li Z, Wahren J, Grunberger G. Diabetologia. 2001;44:889–897. doi: 10.1007/s001250100570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaBonia GJ, Lockwood SY, Heller AA, Spence DM, Hummon AB. Proteomics. 2016;16:1814–1821. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201500524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lockwood SY, Meisel JE, Monsma FJ, Jr, Spence DM. Analytical Chemistry. 2016;88:1864–1870. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luni C, Serena E, Elvassore N. Current Opinion in Biotechnology. 2014;25:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson A, Singh S, Fernekorn U, Schober A. Lab on a Chip. 2013;13:3471–3480. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50237f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]