Abstract

5-Formylcytosine (5fC) is an endogenous DNA modification frequently found within regulatory elements of mammalian genes. Although 5fC is an oxidation product of 5-methylcytosine (5mC), the two epigenetic marks show distinct genome-wide distributions and protein affinities, suggesting that they perform different functions in epigenetic signaling. A unique feature of 5fC is the presence of a potentially reactive aldehyde group in its structure. Here, we show that 5fC bases in DNA readily form Schiff base conjugates with Lys side chains of nuclear proteins in vitro and in vivo. These covalent protein-DNA complexes are reversible (t1/2, 1.8 h), suggesting that they contribute to transcriptional regulation and chromatin remodeling. On the other hand, 5fC mediated DNA-protein cross-links, if present at replication forks or actively transcribed regions, may interfere with DNA replication and transcription.

Keywords: DNA methylation, DNA-protein cross-linking, epigenetics, aldehydes, histone

Table of Contents

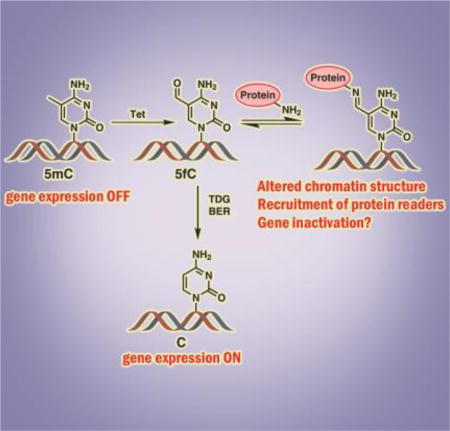

DNA epigenetic mark 5-formylcytosine (5fC), which is generated from 5-methylcytosine via Tet-mediated oxidation, was found to form reversible conjugates with histone proteins in cells. The resulting DNA-protein cross-links involve transient Schiff base formation between Lys chains of proteins and the aldehyde group of 5fC. These reversible DNA-protein conjugates are likely to modify chromatin structure contribute to epigenetic control of gene expression.

DNA methylation is a major mechanism by which eukaryotic cells maintain tissue-specific patterns of gene expression.[1] Cytosine methylation takes place primarily within the context of CpG dinucleotides and is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT).[2] CpG methylation upstream of transcriptional start sites is associated with reduced levels of gene expression, histone deacetylation, and the formation of closed chromatin.[3] Ten eleven translocation dioxygenases (Tet1–3) catalyze iterative oxidation of 5mC to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-formylcytosine (5fC), and 5-carboxylcytosine (5caC).[4] These oxidized forms of 5mC are found in all cells and tissues, although the abundances of 5fC and 5caC in the human genome (0.02 to 0.002% of all Cs)[5] are much lower than those of 5hmC (0.02–0.1 % of all Cs) and 5mC (3–5% of all Cs).[4a, 6] 5hmC concentrations are the highest in neuronal tissues and stem cells and are dramatically decreased in tumors.[7]

Unlike 5mC, which is well known to control the patterns of gene expression in mammalian cells,[1] biological functions of its oxidized forms are incompletely understood. 5fC and 5caC can be replaced with cytosine via the base excision repair pathway,[8] suggesting that they may act as DNA demethylation intermediates. [4a, 8] Recently, it was reported that 5hmC, 5fC, and 5caC are recognized by specialized sets of protein “readers”,[9] leading to a hypothesis that they function as additional epigenetic marks, possibly fine-tuning the levels of gene expression.[1, 10]

Among the oxidized forms of 5mC, 5fC is of particular interest due to the presence of an aldehyde group in its structure. This group is potentially reactive towards cellular nucleophiles such as amino acids, polypeptides, and proteins. Recent proteomics studies have identified a number of nuclear proteins with preferential binding to 5fC in DNA as compared to 5mC, 5hmC and 5caC.[9b, 11] This has led us to hypothesize that the formyl group of 5fC is chemically reactive towards DNA-binding proteins, generating reversible DNA-protein cross-links. Herein, we report that proteins with strong affinity for DNA and containing Lys residues, such as histones H2A and H4, readily form reversible Schiff base conjugates with 5fC-containing DNA. The resulting DNA-protein cross-links (DPCs) involve Lys or Arg side chains of proteins and the formyl group of 5fC (Scheme 1). It is likely that reversible conjugation between regulatory proteins and 5fC in DNA plays a role in chromatin dynamics and epigenetic regulation. Conversely, 5fC mediated DNA-protein conjugates may compromise genetic stability by interfering with DNA replication, transcription, and repair.[12]

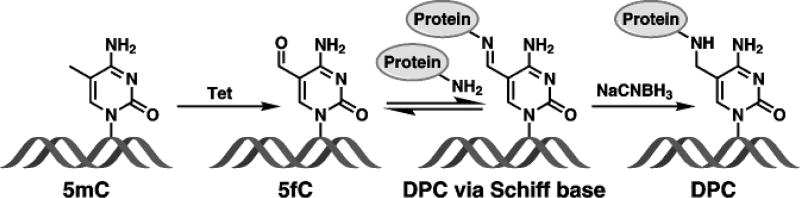

Scheme 1.

Schiff base formation between 5-formyl-dC in DNA and basic side chains of proteins and its chemical stabilization via NaCNBH3 reduction.

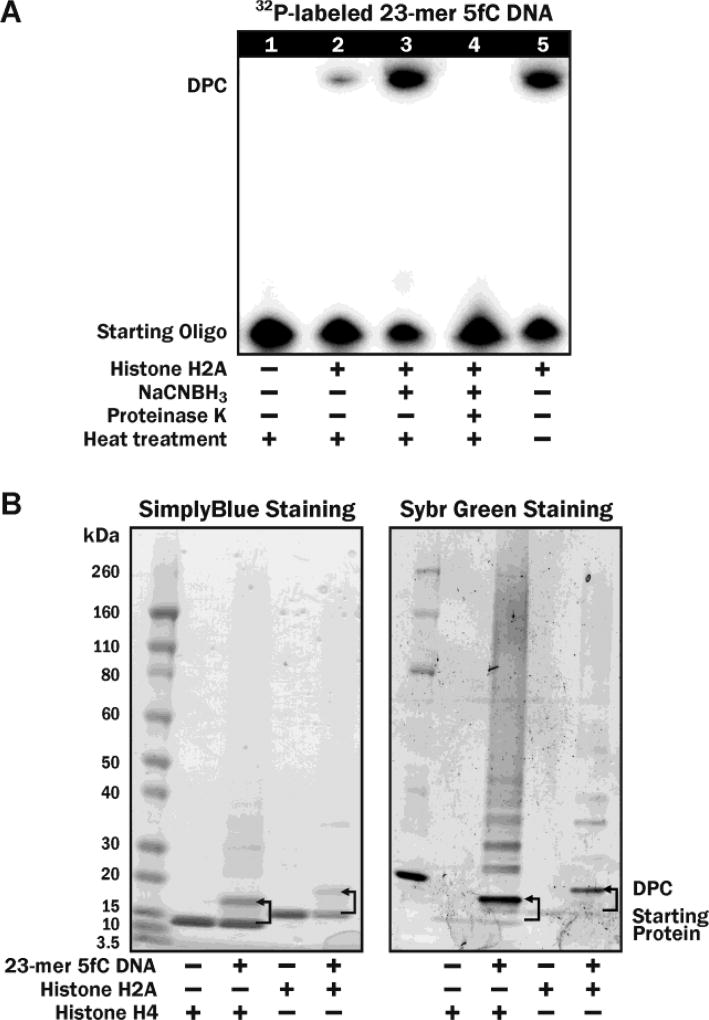

To probe 5fC-mediated DNA-protein cross-linking in vitro, 32P-radiolabeled 5fC-containing DNA (Figure S1A) were incubated with recombinant histone H2A and H4 proteins under physiological conditions, and the formation of covalent DNA-protein conjugates (DPC) was detected as reduced mobility bands on denaturing PAGE (Figure 1A). Strong DPC bands were observed when DNA was incubated with histone proteins (Figure 1A, Lane 5), but not in control experiment in the absence of proteins (Lane 1). The resulting DNA-protein conjugates were partially reversed by heat treatment at 90 °C (Lane 2) and disappeared upon incubation with proteinase K (Lane 4). The reduced mobility bands were confirmed to be DNA-protein conjugates by the fact that they could be visualized by both protein and DNA staining (Figure 1B). The conjugates could be stabilized by reduction in the presence of NaCNBH3 to form irreversible cross-links, which were no longer heat labile (Lane 3 in Figure 1A). These results are consistent with the formation of reversible imino conjugates between histone proteins and 5fC containing DNA, which are converted to stable amino linkages upon treatment with NaCNBH3 (Scheme 1). This was confirmed by mass spectrometry analysis of the conjugates between recombinant histone H4 and 12-mer DNA oligonucleotide (Figure S1B, 5′-AGTCGCTGXTAT-3′, where X = 5fC), which had revealed a strong signal at the expected m/z value of 14,928 (Figure 2). Similar results were obtained for histone H2A (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Denaturing SDS-PAGE analysis of DNA-protein cross-links using (A) 32P-labeled 5fC DNA and (B) SimplyBlue Protein staining (left panel) and SYBR Green DNA staining (right panel).

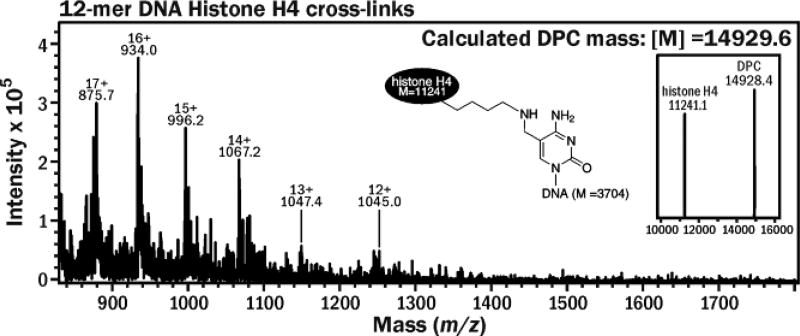

Figure 2.

ESI+ mass spectrum of histone H4 (M = 11,241) cross-linked to 5fC-containing 12-mer oligonucleotide (M = 3704.4). The cross-links were stabilized by NaCNBH3 treatment. The signal at 14,928 corresponds to DPC structure shown on top.

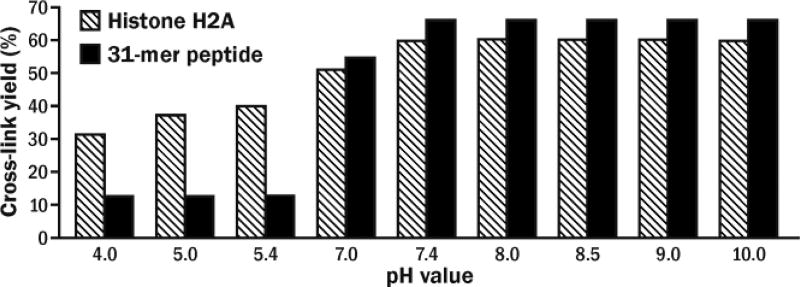

We next examined the effects of protein identity, solution pH, reaction temperature, incubation time, and DNA:protein molar ratio on fC mediated cross-linking efficiency. The highest DPC yields (up to 60%) were achieved following 4 h incubation of histone H2A with 5fC-containing DNA at 25 °C and pH 7.4 (Figures 3 and S3). Higher pH and longer reaction times did not improve DPC yields (Figures 3 and S3). Similar DNA-protein conjugate amounts were observed for histone H2A and Mutyh, while hOGG1, RNAP, and AGT were less efficiently cross-linked (Figure S4 and Table S1). This is not unexpected since histone proteins have a strong affinity for DNA and contain multiple Lys residues available for Schiff base formation with 5fC. Unlike previous reports of thiol-mediated reactions of 5fC,[13] the formation of histone-DNA crosslinks was decreased in presence of β-mercaptoethanol (Figure S5).

Figure 3.

Effects of pH on DNA-protein and DNA-peptide cross-links formation.

The ability of histone proteins to form covalent conjugates with 5fC containing DNA was further confirmed by denaturing PAGE analysis of 47-mer duplexes (see Figure S1C for sequence) which had been incubated with nuclear extracts from human bronchial epithetlial cells (HBEC), although many additional proteins were also captured (Figure S6A). A concentration dependent increase in DPC yield was observed as the 5fC content was increased (Figure S6B).

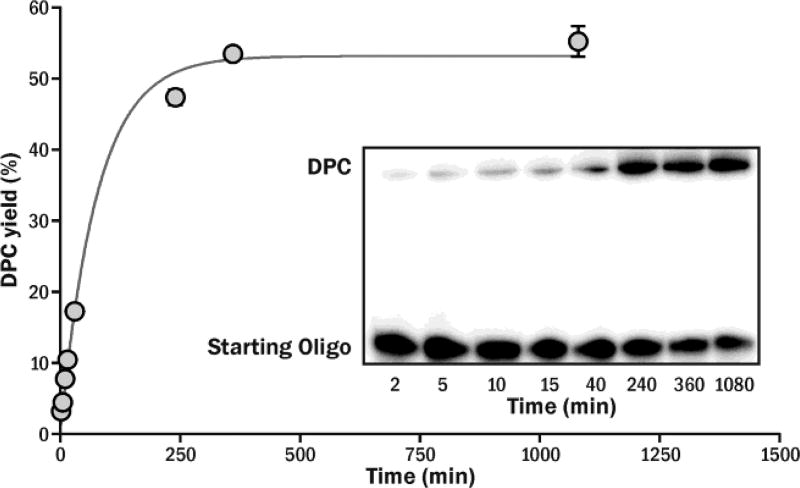

To investigate the stability of the 5fC-protein conjugates, affinity purified cross-links between histone H2A and 32P-labeled 23-mer DNA duplex were incubated under physiological conditions, and the reaction mixtures were analyzed by gel electrophoresis (Figure S7). We found that at 37 °C, 5fC mediated DNA-protein conjugates gradually dissociated to free histones and oligonucleotides. The formation of histone-DNA complexes in the presence of 35-fold molar excess of protein were best described by pseudo-first-order reversible kinetics (Figure 4). The half-life of histone-DNA conjugates under physiological conditions (pH 7.4, 37 °C) was estimated to be 1.8 h (k−1 ~6.1×10−3 min−1).

Figure 4.

Time-dependent DPC formation between 5-formly-dC containing DNA and Histone H2A. The time course of DPC formation fits pseudo first-order reversible kinetics in the presence of 35 molar excess of histone H2A.

To examine the effects of amino acid composition on reactivity of peptides towards 5fC-containing DNA, Lys-containing peptides of varying length and sequence were incubated with 23-mer oligonucleotides containing 5fC (see Figure S1A for DNA sequence and Table S1 for peptide sequences). DNA-peptide conjugates were detected by denaturing PAGE (Figure S8) and characterized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure S9).

We found that the efficiency of cross-linking between 5fC-containing DNA and synthetic polypeptides (11-mer, 31-mer and 57-mer) was much lower as compared to its reactions with proteins (Figure S8 and Table S2).These results suggest that the formation of 5fC-histone conjugates is stimulated by noncovalent DNA-protein interactions, which bring the two biomolecules in a close proximity to each other.

The ability of both Lys and Arg amino acid side chains to form imino conjugates in vitro was further confirmed by ESI-MS and MS2 analysis of the reaction mixtures between 5fC containing DNA and free amino acids (Figure S10). However, not all peptides containing Lys or Arg participated in cross-linking. For instance, no detectable conjugate was formed between DNA and a 10-mer peptide (EQKLISEED, Lane 5 in Figure S8). This can be explained by a reduced affinity of this peptide for DNA due to the negative charges on three glutamic acid side chains.

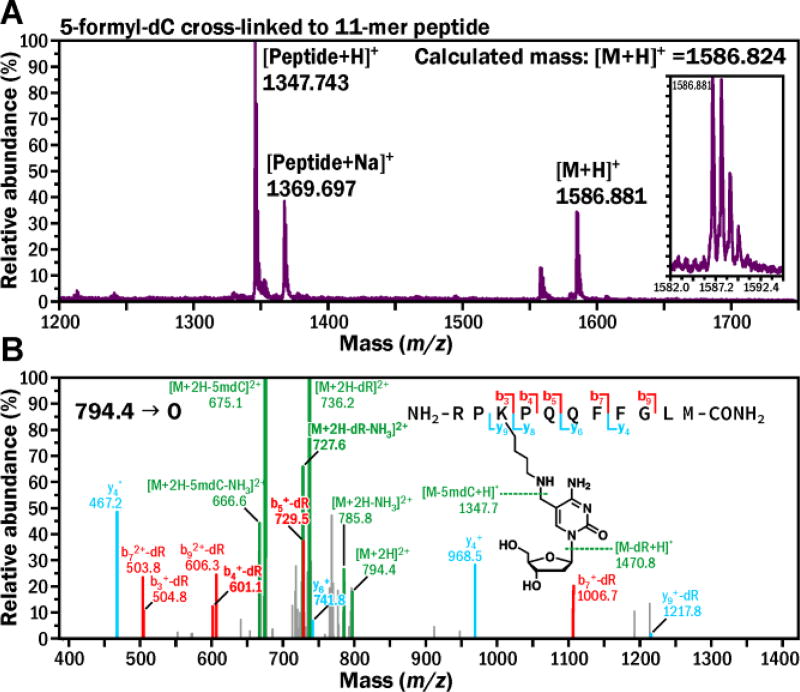

To establish the exact chemical structure of the 5fC-mediated cross-links, 11-mer peptide (RPKPQQFFGLM, M = 1,346.7) was incubated with excess of 5-formyl-dC (M = 255.1) in the presence of NaCNBH3. The resulting peptide-nucleoside conjugates were characterized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (Figure 5A). A prominent signal at m/z 1,586.88 matched the molecular weight of the expected conjugate between the 11-mer peptide and 5-formyl-dC (m/z 1,586.82) (Figure 5A). MS/MS fragmentation of the doubly charged peptide-nucleoside conjugate [M+2H]2+ (m/z 794.4) in an ion trap mass spectrometer was dominated by product ions at m/z 736.2 and 675.1, corresponding to the losses of deoxyribose and nucleoside, respectively, while the b and y ion series were consistent with modification of the K3 lysine residue (Figure 5B). These results are in agreement with the cross-linking mechanism depicted in Scheme 1, where DPC formation between 5fC and Lys involves transient Schiff base formation, which can be stabilized by reduction in the presence of NaCNBH3.

Figure 5.

MS (A) and MS2 (B) spectrum of 11-mer peptide cross-linked to 5-formyl-dC.

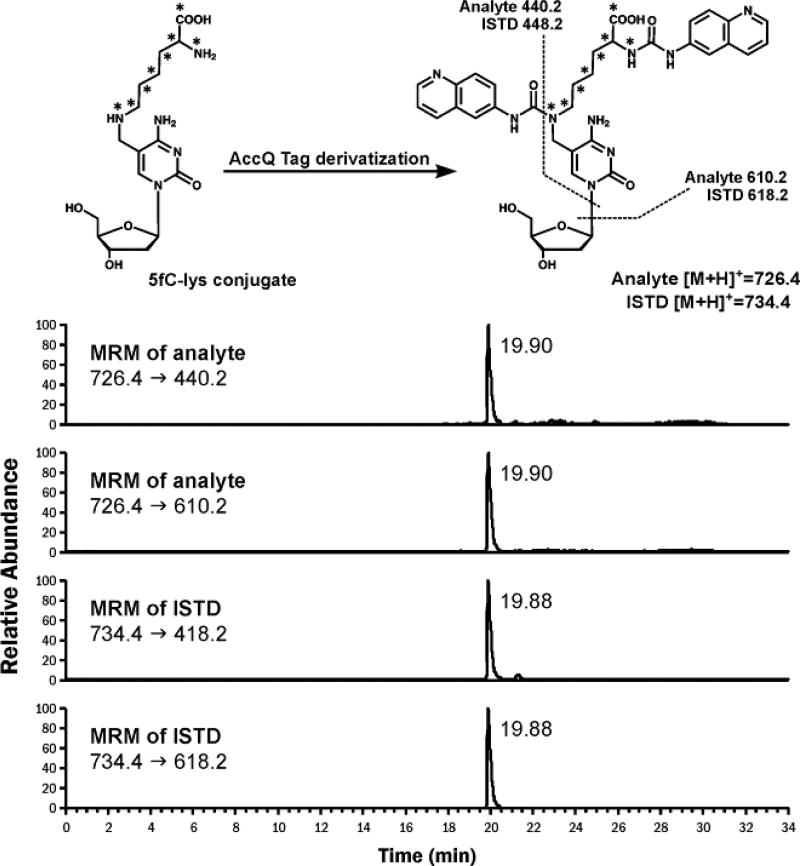

Isotope dilution nanoLC-ESI+-MS/MS methodology was employed to detect 5fC-Lys conjugates in vivo (Figure 6). To stabilize the reversible Schiff base adducts, nuclei isolated from human embryonic kidney 293 cells (HEK293T) were treated with NaCNBH3. Following DNA isolation, samples were digested with proteinase K, nucleases, and phosphatase to yield 5fC-lys conjugates. To facilitate the detection 5fC-lys, they were derivatized with Waters AccQ-Tag, which modified both primary and secondary amines of the analyte, forming a stable derivative (Figure S11). This significantly improved HPLC retention time and peak shape in nanoLC-MS analysis. NanoLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of derivatized samples has revealed a prominent signal with the same HPLC retention time and MS/MS fragmentation as synthetic 5fC-Lys, confirming that Lys side chains indeed form Schiff base adducts to 5-formylcytosine in DNA in cells (Figure 6). 5fC-Lys adduct concentrations in cells were ~ 1.20 ±0.07 ×10−4 % of all dCs. Consequently, about every 100th 5fC base forms a Schiff base with Lys residues of neighboring proteins, based on the quantified amount of 5fC (0.012 % /dC) in untreated HEK293T cells.

Figure 6.

Representative NanoLC-ESI+-MS/MS chromatograms of AccQ-Tag derivatized 5fC-lys conjugates from NaCNBH3 treated nuclei from HEK293T cells.

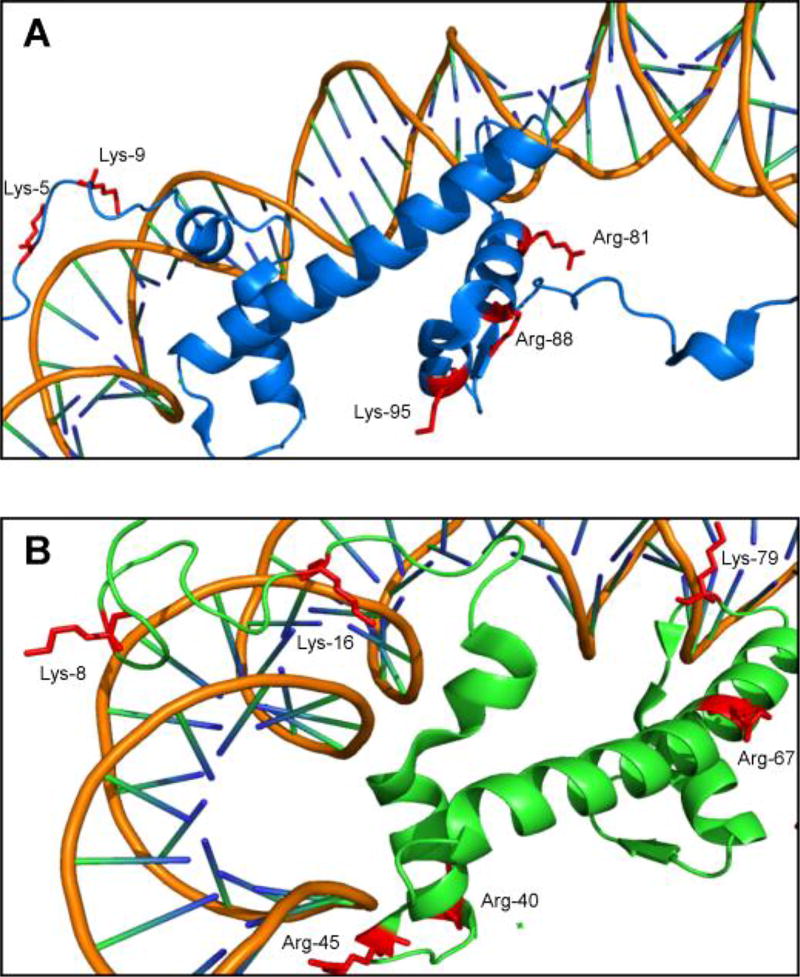

To directly identify amino acid residues participating in histone-DNA cross-linking, DNA component of the reduced histone H4-DNA and histone H2A-DNA conjugates was digested to nucleosides, and the resulting protein-nucleoside conjugates were subjected to tryptic digestion. Tryptic peptides containing cross-links to 5-formyl-dC were detected by nanoLC-ESI+-MS/MS analysis on an Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer. Six lysine or arginine residues from histone H4 (K8, K16, R40, R45, R67 and K79, Table S3) and five from histone H2A (K5, K9, R81, R88 and K95, Table S4) were found to participate in cross-linking to 5fC in DNA (Figure 7). Examination of the crystal structures (PDB IKX5) reveals that many of the residues participating in cross-linking to DNA are located within Lys-rich tails, which are known to interact directly with the DNA duplex within nucleosomal core particles,[14] although some of the participating residues (e.g. R67 in human histone H4) are outside of the DNA binding region.

Figure 7.

Crystal structure of (A) Histone H4 and (B) Histone H2A (PDB IKX5) showing Lys and Arg residues participating in DPC formation.

Future studies are needed to establish possible biological roles of 5fC mediated DNA-protein cross-linking. Greenberg et al. recently reported that lysine residues located in N-terminal tails of histone proteins form Schiff base conjugates with apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites in DNA, which facilitates their repair via base excision mechanism.[15] In vivo concentrations of 5fC and AP sites in genomic DNA are comparable (2~20 vs. 5~20 per 106 nucleosides).[5, 16] It is possible that by analogy with AP sites, histones may facilitate base excision repair of 5fC by TDG and its replacement with cytosine, ultimately leading to erasure of this epigenetic mark.[8]

Despite their relatively low global concentrations, 5fC levels at specific loci (e.g. poised enhancer regions) are comparable to those of other 5mC derivatives.[17] 5fC appears to be a relatively stable epigenetic modification in mammals.[9a, 13a] 5fC is capable of altering local DNA structure, which may play a role in DNA-protein interactions.[9a, 13a] Mass spectrometry based proteomics screens have identified a range of 5fC binding proteins including transcriptional regulators, DNA repair factors, chromatin regulators, and other nuclear proteins not likely to be involved in DNA demethylation.[9b, 11] These data suggest that beyond its function as an active demethylation intermediate, 5fC may act as a functional epigenetic mark involved in transcriptional regulation and possibly other biological functions.[9b, 10d, 17b]

Our recent studies have found that 5fC mediated DNA-histone cross-links significantly block DNA and RNA polymerases. In contrast, DNA-peptide cross-links, which are likely to form as a result of proteolytic degradation of DPCs by specialized proteases such as Spartan,[18] can be bypassed by TLS polymerase, resulting in C to T transition mutations (S. J. and N. T., manuscript in preparation). Given the relatively slow hydrolysis rate of the Schiff base conjugates formed between nuclear proteins and 5fC in DNA, it will be of interest to determine how cells deal with endogenous DNA-histone cross-links, which are expected to present a major physical challenge to DNA transactions due to their bulky size.

Note: While this manuscript was under revision, Li et al.[19] reported 5fC mediated DNA-protein cross-linking in vitro using reconstituted nucleosomal core particles, supporting these findings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Xun Ming and Peter Villalta (University of Minnesota) for their help with MS analysis and Robert Carlson (University of Minnesota) for preparing graphics for this manuscript. This research was supported by a grant from the NIEHS (ES023350). S. J. was partially supported by Wayland E. Noland fellowship from the University of Minnesota.

Footnotes

Complete experimental procedures, MS data, representative gel images, HPLC data. The Supporting Information is available free of charge online.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Jones PA, Takai D. Science. 2001;293:1068–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1063852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Turek-Plewa J, Jagodzinski P. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2005;10:631–647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Goll MG, Bestor TH. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2005;74:481–514. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.010904.153721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bird AP, Wolffe AP. Cell. 1999;99:451–454. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Ito S, Shen L, Dai Q, Wu SC, Collins LB, Swenberg JA, He C, Zhang Y. Science. 2011;333:1300–1303. doi: 10.1126/science.1210597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hu L, Lu J, Cheng J, Rao Q, Li Z, Hou H, Lou Z, Zhang L, Li W, Gong W, Liu M, Sun C, Yin X, Li J, Tan X, Wang P, Wang Y, Fang D, Cui Q, Yang P, He C, Jiang H, Luo C, Xu Y. Nature. 2015;527:118–122. doi: 10.1038/nature15713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfaffeneder T, Hackner B, Truß M, Münzel M, Müller M, Deiml CA, Hagemeier C, Carell T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;123:7146–7150. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Globisch D, Munzel M, Muller M, Michalakis S, Wagner M, Koch S, Bruckl T, Biel M, Carell T. PLoS. One. 2010;5:e15367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jin SG, Jiang Y, Qiu R, Rauch TA, Wang Y, Schackert G, Krex D, Lu Q, Pfeifer GP. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7360–7365. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He Y-F, Li B-Z, Li Z, Liu P, Wang Y, Tang Q, Ding J, Jia Y, Chen Z, Li L, Sun Y, Li X, Dai Q, Song C-X, Zhang K, He C, Xu G-L. Science. 2011;333:1303–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1210944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Bachman M, Uribe-Lewis S, Yang X, Burgess HE, Iurlaro M, Reik W, Murrell A, Balasubramanian S. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:555–557. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Spruijt Cornelia G, Gnerlich F, Smits Arne H, Pfaffeneder T, Jansen Pascal WTC, Bauer C, Münzel M, Wagner M, Müller M, Khan F, Eberl HC, Mensinga A, Brinkman Arie B, Lephikov K, Müller U, Walter J, Boelens R, van Ingen H, Leonhardt H, Carell T, Vermeulen M. Cell. 2013;152:1146–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Pastor WA, Aravind L, Rao A. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:341–356. doi: 10.1038/nrm3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang Y, Chavez L, Chang X, Wang X, Pastor WA, Kang J, Zepeda-Martinez JA, Pape UJ, Jacobsen SE, Peters B, Rao A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014;111:1361–1366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322921111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Nabel CS, Manning SA, Kohli RM. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:20–30. doi: 10.1021/cb2002895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Song C-X, He C. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013;38:480–484. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iurlaro M, Ficz G, Oxley D, Raiber E-A, Bachman M, Booth MJ, Andrews S, Balasubramanian S, Reik W. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R119. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-10-r119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barker S, Weinfeld M, Murray D. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. 2005;589:111–135. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Raiber E-A, Murat P, Chirgadze DY, Beraldi D, Luisi BF, Balasubramanian S. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:44–49. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schiesser S, Pfaffeneder T, Sadeghian K, Hackner B, Steigenberger B, Schröder AS, Steinbacher J, Kashiwazaki G, Höfner G, Wanner KT, Ochsenfeld C, Carell T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:14593–14599. doi: 10.1021/ja403229y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davey GE, Wu B, Dong Y, Surana U, Davey CA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;38:2081–2088. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sczepanski JT, Wong RS, McKnight JN, Bowman GD, Greenberg MM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:22475–22480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012860108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atamna H, Cheung I, Ames BN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:686–691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) Neri F, Incarnato D, Krepelova A, Rapelli S, Anselmi F, Parlato C, Medana C, Dal Bello F, Oliviero S. Cell Rep. 2015;10:674–683. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Booth MJ, Marsico G, Bachman M, Beraldi D, Balasubramanian S. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:435–440. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Vaz B, Popovic M, Newman Joseph A, Fielden J, Aitkenhead H, Halder S, Singh Abhay N, Vendrell I, Fischer R, Torrecilla I, Drobnitzky N, Freire R, Amor David J, Lockhart Paul J, Kessler Benedikt M, McKenna Gillies W, Gileadi O, Ramadan K. Mol. Cell. 2016;64:704–719. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stingele J, Bellelli R, Alte F, Hewitt G, Sarek G, Maslen SL, Tsutakawa SE, Borg A, Kjaer S, Tainer JA, Skehel JM, Groll M, Boulton SJ. Mol. Cell. 2016;64:688–703. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li F, Zhang Y, Bai J, Greenberg MM, Xi Z, Zhou C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:10617–10620. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b05495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.