Abstract

Although grapefruit intake leads to elevated serum estrogen levels when hormones are taken orally, there are no published data on the effect on endogenous levels. We conducted a pilot dietary intervention study among healthy postmenopausal volunteers to test whole grapefruit, 2 juices, and 1 grapefruit soda. Fifty-nine participants were recruited through the Love/Avon Army of Women. The study consisted of a 3-wk run-in, 2 wk of grapefruit intake, and a 1-wk wash-out. Eight fasting blood samples were collected. An additional 5 samples drawn at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 10 hr after grapefruit intake were collected during an acute-phase study for 10 women. Serum assays for estrone (E1), estradiol (E2), estrone-3-sulfate (E1S), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, and sex hormone-binding globulin were conducted. Whole grapefruit intake had significant effects on endogenous E1S. Peak effects were seen at 8 hr, increasing by 26% from baseline. No changes in mean E1 or E2 with whole fruit intake were observed. In contrast, fresh juice, bottled juice, and soda intake all had significant lowering effects on E2. The findings suggest an important interaction between grapefruit intake and endogenous estrogen levels. Because endogenous estrogen levels are associated with breast cancer risk, further research is warranted.

INTRODUCTION

The inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice on the intestinal cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) system interacts with more than 60% of orally administered drugs leading to elevation of their serum concentrations (1, 2). Consumption of a single 6 oz glass can produce the maximal acute pharmacokinetic effect (3–6), with enhanced oral drug bioavailability occurring up to 24 h after consumption (1, 7). An effect is seen with the whole fruit as well as with the juice (8, 9), and chronic consumption may enhance the magnitude of the effect (1, 10). Furanocoumarins have been identified as the active ingredient in grapefruit responsible for this CYP3A4 effect (11).

Grapefruit intake leads to elevated serum levels of estrogens when they are administered orally (12). Schubert et al. found that, after subtracting pretreatment levels, grapefruit juice increased the 48-h area under the curve (AUC) of estradiol (E2) approximately 40% after a single oral dose of E2 in ovariectomized women (13). Weber et al. found that grapefruit juice increased the peak serum concentration of ethinylestradiol (EE2) by 38% and the 24-h AUC by 28% (14). Because endogenous estrogens are also partially metabolized by CYP3A4, it is possible that grapefruit intake could also elevate endogenous estrogen levels; there are no published data on this.

Elevated endogenous estrogen levels significantly increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women (15). Therefore, it is biologically plausible that regular intake of grapefruit would increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer mediated through the effect on estrogen levels. To follow up on the hypothesis, we investigated in the Multiethnic Cohort Study of 46,080 postmenopausal women with 1,657 incident breast cancers, whether grapefruit consumption was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. We found that risk was 30% higher in women who consumed the equivalent of one-quarter of a fresh grapefruit or more per day (16). The association was seen in never-users of postmenopausal hormone therapy (HT) as well as in HT users. However, subsequent studies have not found an overall association and in the Nurses’ Health Study, stratification by HT showed a significant decrease in breast cancer risk with greater intake of grapefruit in women who never used hormone therapy (17, 18).

To begin to clarify the issue, we have conducted a dietary intervention study to examine whether endogenous levels are significantly affected by grapefruit consumption. The purpose was to establish the foundation for a future, large randomized trial by elucidating the issues/questions of conducting such a dietary study. For example, we included 4 grapefruit products to investigate whether effects on endogenous hormones would be the same for different products. We took multiple blood specimens over a 6-wk period to understand the time frame/parameters of any observed effect. We included a heterogeneous group of women and we measured several hormones, not just one as in previous studies. This study provides guidance for future research about a potentially important breast cancer risk factor.

METHODS

Recruitment

Our plan was to recruit 60 postmenopausal volunteers to the study. The majority of volunteers (48 women) were recruited through the Love/Avon Army of Women with the active support of the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation. Twelve other women were recruited in response to personal communications. The 6-wk study consisted of a run-in (baseline) period of 3 wk, a 2-wk period of grapefruit consumption, followed by a 1-wk wash-out period.

Study Population

To minimize potential confounding effects, we restricted recruitment to women meeting the following criteria: healthy, non-smokers aged 50–66 yr; 1 yr or more since last menstrual period; not currently taking any hormones by pill, injection, cream, or patch; no treatment for cancer in past 5 yr; not taking medication for which prescribing information warns against consuming grapefruit (see Supplemental Data); and no antibiotic use in the prior 2 mo. We also required participants to not use certain dietary supplements or herbal products (e.g., Echinacea, St. John’s Wort, black cohosh, or grapefruit extract), and to not consume alcohol or any food or beverage that contains grapefruit or other fruit containing furanocoumarins. A detailed questionnaire, which enumerated all of these items and drugs, was completed by potential participants with the assistance of the study coordinator to help them to identify these products. Participants were further required to refrain from over-the-counter medications beginning 3 days (72 hr) before blood collection and to fast overnight. Reminder telephone calls were placed to each subject beginning 3 days before each blood draw.

Ten of the volunteers also participated in the acute-phase study, which involved multiple blood samples on the first day that they consumed whole grapefruit. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Southern California approved the study and all study participants provided informed consent.

Blood and Data Collection

Two fasting blood samples were collected during the run-in period: one on the morning of Day 14 and one on the morning of Day 21 before starting grapefruit consumption. (The first study day is noted as Day 0.) Grapefruit products were consumed daily for 14 days starting on Day 21 and ending on Day 35. Five fasting blood samples were collected during that period: on Days 22, 24, 26, 28, and 35 before consuming their grapefruit product. A final fasting blood sample was collected on Day 42 after the participant had refrained from any grapefruit consumption for 1 wk.

Five additional blood samples were collected on Day 21 from the women who volunteered for the acute-phase study: at 1, 2, 4, 8 and 10 h after consuming one half of a fresh whole grapefruit. Standard meals (breakfast, lunch, and dinner) plus beverages were provided for these participants.

Blood samples were collected by venipuncture. Specimens were stored in an ice chest until transport to the laboratory at USC for processing. Blood components were separated and stored in aliquots at −80°C within 4 h of collection.

Each day we collected a blood specimen, participants were asked to complete a 1-page Specimen Collection Questionnaire (SCQ) prior to blood draw. This questionnaire recorded the time of blood collection, the time the participant last had anything to eat or drink, and information about the intake of alcohol, tea, soy, lime products, medications, and supplements during the previous 24-h period. Subjects also reported physical activity on the SCQ.

Grapefruit Product

Participants were assigned to 1 of 4 groups: 1) one half of whole fresh grapefruit (“whole”); 2) fresh squeezed juice “not from concentrate”, found in the refrigerated section of the grocery store (“fresh juice”); 3) bottled juice from concentrate, not refrigerated (“bottled juice”); and 4) carbonated grapefruit soda (“soda”). Grapefruit products were provided to participants. All participants in the acute phase of the study were in the one-half of whole grapefruit group.

Whole grapefruit was purchased from a single Costco store under the brand name “Texas Red Grapefruit.” We provided 4 whole fruits per wk of the same variety from the same store batch. Subjects were instructed to eat one half of the fruit each morning (after blood collection) and save the second half for the following day. We selected Simply Grapefruit 100% Pure Squeezed Grapefruit Juice and Ocean Spray 100% White Grapefruit Juice for the 2 juices. Participants were asked to consume a standard juice glass (6 oz) each morning. For both, we purchased enough to cover each week of the study, mixed the contents of all containers into 1 batch, and gave a full bottle to each participant on Day 21. On Day 28, each subject received a new bottle of freshly mixed juice. We selected regular 12 oz cans of “Squirt” for the participants assigned grapefruit soda. Participants were asked to consume 1 can per day, by early afternoon, during the intervention period.

Hormone Assessment

Serum assays for E1, E2, E1S, DHEAS, and SHBG were conducted in the Reproductive Endocrine Research Laboratory at University of Southern California under the supervision of Dr. Frank Stanczyk. For all assay batches, we included blinded duplicate samples to measure reproducibility of results. All samples of the same individual were analyzed together in the same batch to control for interassay variation. E1 and E2 were quantified by validated radioimmunoassays (RIAs) with preceding organic solvent extraction and Celite column partition chromatography (19). The assay sensitivities are 4 pg/mL and 2 pg/mL for the E1 and E2 assays, respectively. The coefficients of variation (CVs) for E1 are 11.1% and 9.1% at 28 pg/mL and 69 pg/mL, respectively, and for E2 are 10.3% and 9.6% at 18 pg/mL and 42 pg/mL, respectively. E1S was measured by direct RIA using a commercial kit (Beckman Coulter, Minneapolis, MN) (20). The assay sensitivity is 50 pg/mL and the interassay CVs are 7.0% and 8.0% at E1S concentrations of 0.49 ng/mL and 13.2 ng/mL, respectively. SHBG was measured by solid-phase, 2-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay on the Immulite 2000 analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). The assay sensitivity is 1 nmol/L, and the interassay CVs are 5.2%, 5.2%, and 6.6% at SHBG concentrations of 21 nmol/L, 63 nmol/L, and 80 nmol/L, respectively. DHEAS was measured by a direct solid-phase, competitive chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay on the Immulite 2000 analyzer. The assay sensitivity is 3 μg/dL, and the interassay CVs are 13%, 9.8%, and 9.3% at DHEAS concentrations of 52 μg/dL, 163 μg/dL, and 214 μg/dL, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

We quantified the chronic effect of grapefruit intake by comparing measurements of E1, E2, E1S, and SHBG taken during grapefruit intervention to the mean of the 2 measurements obtained during the run-in phase (“baseline”). All calculations used logarithmically transformed values to achieve more normal distributions. Results are reported as percentage change; for example, we first calculated the mean difference [log (E1post) − log (E1baseline)] and then converted to percent change [exp(mean)−1) × 100]. The final calculation measured change between the final draw (after the 1 wk wash-out) and baseline. The chronic effect of grapefruit intake on circulating DHEAS levels was not measured.

We quantified the acute effect of grapefruit intake by comparing measurements of E1, E2, E1S, DHEAS, and SHBG taken at 1, 2, 4, 8, and 10 h post initial grapefruit intake to the measurement obtained immediately before initial grapefruit intake.

Statistical significance calculations were based on Student’s t-test using the within-person differences on the log transformed values and reported as 2-sided significance levels (P values). SAS and Stata statistical software packages were used to perform calculations.

RESULTS

Sixty women participated in the study; 10 of whom also participated in the acute-phase study. One woman was later dropped from the analysis due to serum hormone evidence that she was taking an estrogenic product at baseline.

Baseline characteristics of the final sample of 59 women according to grapefruit product consumed are shown in Table 1. The majority of participants were non-Hispanic Whites (72%), followed by Latinas (17%) and Asians (7%). Weight (kg) and body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) were significantly correlated with baseline E1, E2, and SHBG; E1 and E2 were higher in heavier women and SHBG was lower. The relationships with BMI were slightly more statistically significant than the relationships with weight, and BMI was used in the statistical analyses. Age was significantly correlated with baseline E2 and SHBG; E2 was lower and SHBG was higher in older women. Baseline E1S was not related to BMI or age. Hours fasting, vigorous physical activity and whether the subject was trying to lose weight were not correlated with hormone values. Intakes of alcohol, tea, and soy were also not correlated with hormone values.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of participating subjects by grapefruit product intervention

| Whole | Fresh juice | Bottled juice | Soda | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 16 | 16 | 13 | 14 |

| Age at enrollment, mean (SD) | 57.8 (4.0) | 57.4 (4.5) | 58.9 (3.9) | 55.5 (4.1) |

| Weight at enrollment, mean (SD) | 73.4 (14.9) | 67.9 (11.9) | 76.5 (16.8) | 73.7 (13.1) |

| BMI at enrollment, mean (SD) | 27.3 (6.2) | 25.2 (4.5) | 27.8 (5.9) | 26.7 (4.1) |

| Age at menopause, median (IQR) | 51 (49, 53) | 52 (48, 54) | 49 (38, 51) | 48 (46, 50) |

| Baseline hormone levels, median (IQR)1 | ||||

| E1 | 36.5 (22.0, 42.8) | 34.1 (23.6, 37.6) | 33.6 (30.5, 35.6) | 26.1 (19.5, 33.2) |

| E2 | 10.8 (6.9, 14.3) | 7.3 (5.4, 11.4) | 10.5 (6.8, 12.2) | 9.3 (7.2, 12.0) |

| E1S | 0.74 (0.56, 0.87) | 0.69 (0.55, 0.83) | 0.78 (0.69, 0.94) | 0.76 (0.63, 0.81) |

| SHBG | 44.6 (27.2, 54.7) | 56.5 (31.7, 78.5) | 52.8 (40.2, 76.9) | 46.2 (36.3, 61.9) |

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range.

Calculated directly (rather than using normal approximation) from two baseline observations.

The intra-assay CVs for 27 blind duplicates were 2.1% for E1, 4.9% for E2, 5.1% for E1S, and 1.1% for SHBG. The mean percent changes from the first baseline blood draw on Day 14 to the second baseline blood draw 1 wk later were −1.5%, −5.3%, 2.0%, and 1.3% for E1, E2, E1S, and SHBG, respectively. Mean percent changes (and 95% confidence limits) in E1, E2, and E1S at 24 h, over 2 wk of regular intake and 1 wk after stopping intake of the 4 grapefruit product interventions are shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4, respectively. We found no effect of grapefruit product intake on SHBG at any of the 3 time points for any of the four products tested. Hormone assay results for E1, E2, E1S, and DHEAS are described by grapefruit product.

TABLE 2.

Percent change in E1 after grapefruit product intervention

| Whole | Fresh juice | Bottled juice | Soda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | |

| at 24 hours | 0.6 | 0.92 | −8.8 | 0.042 | −8.9 | 0.024 | −8.6 | 0.095 |

| −10.7, 13.3 | −16.5, −0.4 | −15.7, −1.4 | −18.0, 1.8 | |||||

| over 2 weeks | 7.5 | 0.10 | 3.3 | 0.40 | −2.1 | 0.45 | −8.2 | 0.023 |

| −1.7, 17.6 | −4.7, 12.0 | −7.7, 3.8 | −14.5, −1.4 | |||||

| at 1 week after stopping | 0.9 | 0.84 | 1.7 | 0.71 | −7.9 | 0.18 | −4.9 | 0.36 |

| −8.2, 10.9 | −7.3, 11.4 | −18.8, 4.4 | −15.3, 6.8 | |||||

Percent change.

95% confidence interval.

TABLE 3.

Percent change in E2 after grapefruit product intervention

| Whole | Fresh juice | Bottled juice | Soda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | |

| at 24 hours | −8.7 | 0.097 | −12.2 | 0.015 | −19.3 | 0.011 | −14.6 | 0.006 |

| −18.2, 1.9 | −20.7, −2.9 | −30.9, −5.8 | −23.0, −5.3 | |||||

| over 2 weeks | −1.1 | 0.76 | −6.7 | 0.042 | −8.4 | 0.021 | −6.7 | 0.16 |

| −8.5, 6.9 | −12.7, −0.3 | −14.7, −1.6 | −15.5, 3.1 | |||||

| at 1 week after stopping | −9.3 | 0.080 | −13.1 | 0.023 | −23.2 | 0.003 | −13.4 | 0.025 |

| −18.8, 1.3 | −22.8, −2.2 | −34.0, −10.6 | −23.3, −2.1 | |||||

Percent change.

95% confidence interval.

TABLE 4.

Percent change in E1S after grapefruit product intervention

| Whole | Fresh juice | Bottled juice | Soda | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | %* | P | |

| at 24 hours | 15.7 | 0.008 | 3.6 | 0.23 | 3.9 | 0.41 | −4.4 | 0.16 |

| 4.5, 28.0 | −2.5, 10.1 | −5.7, 14.3 | −10.6, 2.1 | |||||

| over 2 weeks | 11.2 | 0.016 | 2.7 | 0.43 | −1.5 | 0.67 | −4.7 | 0.054 |

| 2.3, 20.9 | −4.3, 10.3 | −8.6, 6.2 | −9.3, 0.1 | |||||

| at 1 week after stopping | 3.2 | 0.46 | −3.1 | 0.29 | −8.5 | 0.068 | −2.0 | 0.64 |

| −5.7, 13.0 | −8.8, 3.0 | −16.9, 0.8 | −10.4, 7.3 | |||||

Percent change.

95% confidence interval.

Whole Grapefruit

There were no overall statistically significant changes in mean E1 or E2 at 24 h after starting grapefruit intake, over the 2 wk of regular intake or at 1 wk after stopping grapefruit intake. Mean E1S was 15.7% higher at 24 h (P = 0.008) and 11.2% higher over the 2 wk of regular intake (P = 0.016); mean E1S returned to baseline at 1 wk after stopping intake.

Fresh Juice

Mean E1 was 8.8% lower at 24 h (P = 0.042); no other statistically significant effects on mean E1 were observed over the 2-wk intervention. Mean E2 was statistically significantly lower at all 3 time points: 12.2% lower at 24 h (P = 0.015), 6.7% lower over the 2 wk of regular intake (P = 0.042), and 13.1% lower after stopping intake (P = 0.023). There were no statistically significant changes in mean E1S at any of the 3 time points.

Bottled Juice

Mean E1 was 8.9% lower at 24 h (P = 0.024); no other significant effects on mean E1 were observed over the intervention. Mean E2 was statistically significantly lower at all 3 time points: 19.3% lower at 24 h (P = 0.011), 8.4% lower over the 2 wk of regular intake (P = 0.021), and 23.2% lower after stopping intake (P = 0.003). There were no statistically significant changes in mean E1S at any of 3 time points.

Soda

Mean E1 was significantly lower (8.2%) over the 2 wk of regular intake (P = 0.023) and returned to baseline at 1 wk after stopping intake. Mean E2 was 14.6% lower at 24 hours (P = 0.006). There was no effect on mean E2 over the 2 wk of regular intake, but the mean level was significantly lower (13.4%) at 1 wk after stopping intake (P = 0.025). We found no statistically significant effects of soda intake on mean E1S levels.

Acute Effects with Whole Grapefruit

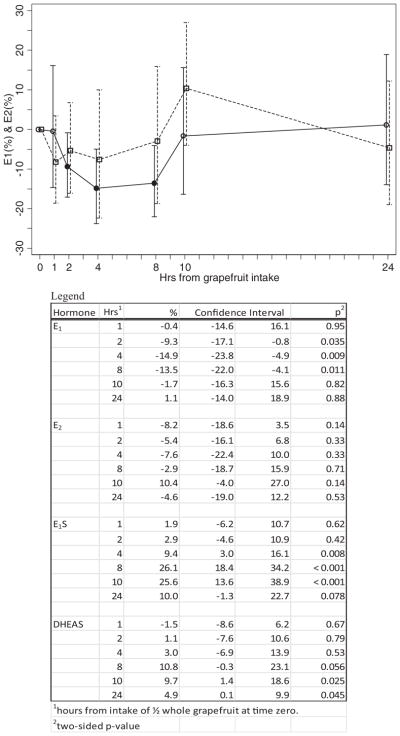

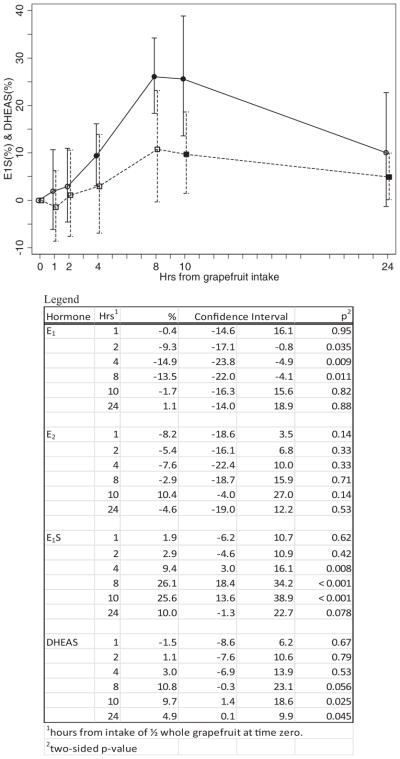

The acute effect of whole grapefruit intake on E1 and E2 levels for the 10 women in this phase are shown in Fig. 1. The mean E1 level decreased by 9.3% at 2 h (95% CI = −17.1%, −0.8%), by 14.9% at 4 h (95% CI = −23.8%, −4.9%) and by 13.5% at 8 h (95% CI = −22.0%, −4.1%). The mean level returned to baseline at 10 hours. There were no statistically significant changes in mean E2. Results for the acute effect of whole grapefruit intake on mean E1S and mean DHEAS levels are shown in Fig. 2. Mean E1S level was increased by 9.4% at 4 h (95% CI = 3.0%, 16.1%), by 26.1% at 8 h (95% CI = 18.4%, 34.2%), and remained at approximately this level at 10 h (25.6% higher; 95% CI = 13.6%, 38.9%). All 10 women experienced an increase in E1S level at 8 and 10 h. At 24 h, the mean E1S level was still 10.0% higher (95% CI = −1.3%, 22.7%). Mean DHEAS levels followed the same pattern as E1S, but at about one-third the percent increase. At 8 h, the mean DHEAS level was increased by 10.8% (95% CI = −0.3%, 23.1%). At 10 h, the mean DHEAS level was 9.7% higher (95% CI = 1.4%, 18.6%). At 24 h, the mean DHEAS level remained significantly elevated compared to baseline: on average, 4.9% higher (95% CI = 0.1%, 9.9%).

FIG. 1.

Percent change* in E1 and E2 among 10 participants in the acute-phase of the study after ½ whole grapefruit was consumed at Time 0. *Mean percent change and 95% confidence interval. The solid symbols are the points that are statistically significant from zero. Solid lines indicate E1; dashed lines indicate E2.

FIG. 2.

Percent change* in E1S and DHEAS among 10 participants in the acute-phase of the study after ½ whole grapefruit was consumed at time zero. *Mean percent change and 95% confidence interval. The solid symbols are the points that are statistically significant from zero. Solid lines indicate E1S; dashed lines indicate DHEAS.

DISCUSSION

Since at least 2002, the FDA-mandated labeling for oral hormone products for postmenopausal women has contained a warning in the Physician Prescribing Information that “grapefruit juice may increase plasma concentrations of estrogens.” Although grapefruit has been shown to lead to elevated serum levels of estrogens when hormones are administered orally (12), there is only our very preliminary finding on the effect of grapefruit intake on endogenous E1 and E2 levels (21). The present study found statistically significant effects, both chronic and acute, of grapefruit intake on endogenous estrogen levels. However, the observed effects were not as we had hypothesized.

Contrary to expectation, there was no effect of whole grapefruit intake on mean serum E1 and E2 levels. We did, however, observe a statistically significant increase in mean E1S. E1S increased within 8 h of initial whole grapefruit consumption and remained elevated during regular intake over the 2-wk intervention—average increase of 11.2%. This 11.2% was seen 24 h after the grapefruit was consumed and it is possible that a much greater increase occurred around 8 to 10 h as was seen in the acute phase study. The acute phase increase in E1S was mirrored in an increase in DHEAS. Although we did not find a strong correlation between the change in DHEAS and E1S in individual women, this finding suggests that the reason for the E1S increase needs to be sought in factors common to the metabolism of these 2 hormones. We have no explanation of why there was no effect on mean serum E1 or E2 levels from whole grapefruit.

Large changes in E1 and E2 after grapefruit intervention were, however, seen in individual women. The magnitude of these changes was of the same order as seen in the changes between the 2 baseline values of E1, E2, E1S, and SHBG. The interquartile range, measuring change between the first and second baseline values, was double the expected interquartile range based on the laboratory CVs: 28.5% for E1, 27.3% for E2, 18.4% for E1S, and 15.3% for SHBG. The correlations between the first and second baseline values were 0.83 for E1, 0.92 for E2, 0.88 for E1S, and 0.97 for SHBG. Although these correlations are greater than were reported from the Nurses’ Health Study when the blood samples were taken some 2 yr apart (22), they do show that hormone values fluctuate widely even over as short a period as a week. Notably, BMI was not associated with the observed fluctuations. Because estrogen levels in postmenopausal women are highly correlated with breast cancer risk (as discussed below), we believe that studies of the reasons for these hormone fluctuations observed at baseline are clearly warranted.

Prospective studies of endogenous sex hormones and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women have found consistent support for a key role of elevated estrogen levels (15, 23). These studies found a strong relation between higher E1S levels and risk. E1S and other estrogens were highly correlated in all of these studies and in the overview of these studies (17) the authors remarked that disassociating the risks from the various estrogens examined was not possible.

E1S is the major circulating form of estrogen in postmenopausal women; circulating levels are 5–10 times higher than circulating levels of E1 and E2 (24). E1S is a substrate for local production of estrogens in normal breast tissue and in breast carcinoma (25). Two principal pathways of local production are the aromatase pathway, which transforms androgens into estrogens, and the sulfatase pathway, which converts E1S into E1 (26).

Numerous studies have indicated a link between the pathogenesis of breast cancer and the expression of enzymes responsible for the local production of estrogens in the breast (27). Breast tissue contains all the enzymes involved in the formation and transformation of estrogens. Of relevance to the present study is steroid sulfatase, which is encoded by the STS gene and hydrolyzes E1S to E1 (27). E1 is subsequently converted to the potent, biologically active E2 by 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (17βHSD) type 1. STS activity is significantly higher in breast cancer tissue than in normal tissue (28, 29) and some authors have suggested that hydrolysis of E1S is a much greater source of E2 in mammary tumors than conversion of androgens, via aromatase, to estrogens (24, 26). It should be noted, however, that the importance of local production of E1 and E2 from precursors in the breast is a matter of serious debate so that precisely how elevated levels of E1S contribute to risk is not known (30).

We designed the current study to test four different grapefruit products. We hypothesized that the manufacturing process for “fresh” juice (“gently pasteurized”) and shelf-stable juice may diminish any effect seen with unprocessed whole fruit. And, we were curious to examine effects of products that were manufactured differently with various ingredients. The findings of the present study suggest that intake of different grapefruit products produce very different effects on naturally circulating hormone levels in postmenopausal women. In contrast to the whole grapefruit, we found statistically significant decreases in E1 and E2 but no effect on E1S for all 3 grapefruit juice/soda products in the study.

Previous studies have found considerable differences on the content of various furanocoumarins in different varieties of grapefruit including different commercially available grapefruit juice brands (9, 31–33). However, the results of the present study suggest that factors other than the furanocoumarin content of various grapefruit products are at play.

Although the majority of published studies have investigated grapefruit–drug interactions mediated primarily through inhibition of the CYP3A4 enzyme system, other mechanisms of interaction have been described (34, 35). Organic anion-transporting polypeptides (OATPs) are a family of proteins involved in the transport of hormones, bile acids, and drugs within the body. Drug transporters help move a drug into cells for absorption. Recent studies have found that substances in grapefruit juice block the action of transporters and, as a result, less of the drug is absorbed (34, 36). The latter mechanism is clearly intriguing. Because OATPs are involved in the transport of sulfated steroid hormones such as E1S and DHEAS, their potential importance on steroid hormone formation and metabolism after grapefruit intake needs to be explored.

In a report from the Nurses’ Health Study, Kim et al. found that stratification by HT showed a significant decrease in breast cancer risk with greater intake of grapefruit in women who never used hormone therapy (17). Although we find support for increased breast cancer risk based on our whole grapefruit E1S results, our findings for the 3 grapefruit juice/soda products tested in the current study provide support for the protective association observed in the Nurses’ Health Study.

When we designed this study, we imagined that if there was an effect of grapefruit intake on endogenous hormone levels, that effect would be clear and easily characterized. However, our results confirm that the process of hormone metabolism and absorption is complicated. We need carefully controlled pharmacokinetic studies to understand the findings of the present study. Dietary prevention strategies represent a relatively unexplored but potentially important approach for reducing the risk of breast cancer. The clinical impact may be considerable and would extend to multiple racial/ethnic populations. Furthermore, grapefruit intake could have implications for any cancer for which circulating hormone levels are associated with risk. The findings of the present study illustrate the importance of understanding, in detail, the interactions between grapefruit consumption and serum hormone levels, particularly the effects of long-term consumption. Creative new approaches are warranted to elucidate the causes of breast cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funds from the California Breast Cancer Research Program of the University of California, Grant Number 14IB-0019. Special thanks to the Love/Avon Army of Women (www.armyofwomen.org) and the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation for providing a valuable resource through which we were able to recruit study participants. We are especially grateful to the women who volunteered to participate in this research study.

Contributor Information

Kristine R. Monroe, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, California, USA

Frank Z. Stanczyk, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, California, USA, and Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Kathleen H. Besinque, School of Pharmacy, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, USA

Malcolm C. Pike, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California/Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, California, USA, and Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA

References

- 1.Bailey DG, Dresser GK. Interactions between grapefruit juice and cardiovascular drugs. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2004;4:281–297. doi: 10.2165/00129784-200404050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maskalyk J. Grapefruit juice: potential drug interactions. Can Med Assoc J. 2002;167:279–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahan A, Altman H. Food-drug interaction: grapefruit juice augments drug bioavailability—mechanism, extent and relevance. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edgar B, Bailey D, Bergstrand R, Johnsson G, Regardh CG. Acute effects of drinking grapefruit juice on the pharmacokinetics and dynamics of felodipine—and its potential clinical relevance. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1992;42:313–317. doi: 10.1007/BF00266354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundahl J, Regardh CG, Edgar B, Johnsson G. Effects of grapefruit juice ingestion—pharmacokinetics and haemodynamics of intravenously and orally administered felodipine in healthy men. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:139–145. doi: 10.1007/s002280050263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundahl JU, Regardh CG, Edgar B, Johnsson G. The interaction effect of grapefruit juice is maximal after the first glass. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1998;54:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s002280050424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greenblatt DJ, von Moltke LL, Harmatz JS, Chen G, Weemhoff JL, et al. Time course of recovery of cytochrome p450 3A function after single doses of grapefruit juice. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:121–129. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00118-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey DG, Dresser GK, Kreeft JH, Munoz C, Freeman DJ, et al. Grapefruit-felodipine interaction: effect of unprocessed fruit and probable active ingredients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2000;68:468–477. doi: 10.1067/mcp.2000.110774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda K, Guo L, Ohashi N, Yoshikawa M, Yamazoe Y. Amounts and variation in grapefruit juice of the main components causing grapefruit–drug interaction. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2000;741:195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lown KS, Bailey DG, Fontana RJ, Janardan SK, Adair CH, et al. Grapefruit juice increases felodipine oral availability in humans by decreasing intestinal CYP3A protein expression. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:2545–2553. doi: 10.1172/JCI119439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paine MF, Widmer WW, Hart HL, Pusek SN, Beavers KL, et al. A furanocoumarin-free grapefruit juice establishes furanocoumarins as the mediators of the grapefruit juice-felodipine interaction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:1097–1105. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.5.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medical Letter. Drug interactions with grapefruit juice. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:429–431. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200502000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schubert W, Cullberg G, Edgar B, Hedner T. Inhibition of 17 beta-estradiol metabolism by grapefruit juice in ovariectomized women. Maturitas. 1994;20:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0378-5122(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber A, Jager R, Borner A, Klinger G, Vollanth R, et al. Can grapefruit juice influence ethinylestradiol bioavailability? Contraception. 1996;53:41–47. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(95)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Endogenous Hormones and Breast Cancer Collaborative Group. Endogenous sex hormones and breast cancer in postmenopausal women: reanalysis of nine prospective studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:606–616. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monroe KR, Murphy SP, Kolonel LN, Pike MC. Prospective study of grapefruit intake and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:440–445. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim EH, Hankinson SE, Eliassen AH, Willett WC. A prospective study of grapefruit and grapefruit juice intake and breast cancer risk. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:240–241. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spencer EA, Key TJ, Appleby PN, van Gils CH, Olsen A, et al. Prospective study of the association between grapefruit intake and risk of breast cancer in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:803–809. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9310-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Probst-Hensch NM, Ingles SA, Diep AT, Haile RW, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Aromatase and breast cancer susceptibility. Endocr Relat Cancer. 1999;6:165–173. doi: 10.1677/erc.0.0060165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slater CC, Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Shoupe D, Paulson RJ, et al. Markedly elevated levels of estrone sulfate after long-term oral, but not transdermal, administration of estradiol in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2001;8:200–203. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monroe KR, Murphy SP, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Dietary fiber intake and endogenous serum hormone levels in naturally postmenopausal Mexican American women: the multiethnic cohort study. Nutr Cancer. 2007;58:127–135. doi: 10.1080/01635580701327935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hankinson SE, Manson JE, Spiegelman D, Willett WC, Longcope C, et al. Reproducibility of plasma hormone levels in postmenopausal women over a 2–3-year period. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4:649–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baglietto L, Severi G, English DR, Krishnan K, Hopper JL, et al. Circulating steroid hormone levels and risk of breast cancer for postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:492–502. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasqualini JR. The selective estrogen enzyme modulators in breast cancer: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1654:123–143. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki T, Miki Y, Nakamura Y, Moriya T, Ito K, et al. Sex steroid-producing enzymes in human breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:701–720. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.00834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pasqualini JR, Chetrite GS. Recent insight on the control of enzymes involved in estrogen formation and transformation in human breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;93:221–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulendran M, Salhab M, Mokbel K. Oestrogen-synthesising enzymes and breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1095–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pasqualini JR. Breast cancer and steroid metabolizing enzymes: the role of progestogens. Maturitas. 2009;65(Suppl 1):S17–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chetrite GS, Thomas JL, Shields-Botella J, Cortes-Prieto J, Philippe JC, et al. Control of sulfatase activity by nomegestrol acetate in normal and cancerous human breast tissues. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:2827–2830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lonning PE, Haynes BP, Straume AH, Dunbier A, Helle H, et al. Exploring breast cancer estrogen disposition: the basis for endocrine manipulation. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:4948–4958. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Messer A, Nieborowski A, Strasser C, Lohr C, Schrenk D. Major furocoumarins in grapefruit juice I: levels and urinary metabolite(s) Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49:3224–3231. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wanwimolruk S, Marquez PV. Variations in content of active ingredients causing drug interactions in grapefruit juice products sold in California. Drug Metabol Drug Interact. 2006;21:233–243. doi: 10.1515/dmdi.2006.21.3-4.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widmer W, Haun C. Variation in furanocoumarin content and new furanocoumarin dimers in commercial grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macf.) juices. J Food Sci. 2005;70:C307–C312. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hanley MJ, Cancalon P, Widmer WW, Greenblatt DJ. The effect of grapefruit juice on drug disposition. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:267–286. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.553189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seden K, Dickinson L, Khoo S, Back D. Grapefruit–drug interactions. Drugs. 2010;70:2373–2407. doi: 10.2165/11585250-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tapaninen T, Neuvonen PJ, Niemi M. Grapefruit juice greatly reduces the plasma concentrations of the OATP2B1 and CYP3A4 substrate Aliskiren. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:339–342. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.