Abstract

Conceptual frameworks bring together existing theories and models in order to identify, consolidate, and fill in gaps between theory, practice, and evidence. Given the vast number of possible outcomes that could be studied in genetic counseling, a framework for organizing outcomes and postulating relationships between communication services and genetic counseling outcomes was sought. Through an iterative approach involving literature review, thematic analysis, and consolidation, outcomes and processes were categorized to create and define components of a conceptual framework. The final product, “Framework for Outcomes of Clinical commUnication Services” (FOCUS) contains the following domains: communication strategy; communication process measures; patient care experience, patient changes, patient health; and family changes. A website was created to allow easier access and ongoing modifications to the framework. In addition, a step-by-step guide and two examples were created to show flexibility in how the framework can be used. FOCUS may help in conceptualizing, organizing and summarizing outcomes research related to risk communication and counseling in genetic service delivery as well as other healthcare settings.

Keywords: Evaluation, patient outcomes, genetic services, genetic counseling, patient communication, family communication, cascade testing

INTRODUCTION

Measuring the impact of genetic counseling (GC) on patient outcomes is critical for improving patient care and establishing the added value and quality of care provided by genetic counselors. Clinical communication encompasses many of the education, counseling, and care coordination processes that genetic counselors perform. Clinical communication is a critical component of patient-centered care and may influence patient health outcomes indirectly through cognitive, emotional, or behavioral patient changes that occur as a result of clinical services (Nci, DCCPS, & Arp, 2007; Street, 2013; Street, Makoul, Arora, & Epstein, 2009).

We and other researchers have recognized that a comprehensive conceptual framework would be helpful in promoting the use of theory in practice and research related to clinical communication processes and outcomes (Marion McAllister, Moldovan, Paneque, & Skirton, 2016). A framework can be defined as “a structure, overview, outline, system or plan consisting of various descriptive categories, e.g. concepts, constructs or variables…that are presumed to account for a phenomenon” (Nilsen et al., 2015). A framework could help guide hypothesis driven research, selection of outcome measures, and the development of a systematic approach to evaluate the impact of a communication strategy on patient outcomes. Furthermore, use of a conceptual framework helps ensure that potentially important factors have been considered as part of an outcomes assessment (Glanz & Bishop, 2010). Finally, a framework can help in hypothesizing and testing proposed relationships between GC communication processes and outcomes (Glanz & Bishop, 2010).

Prior efforts to develop a conceptual framework for evaluating genetic service delivery have been made using different approaches. Wang et al. reviewed the scientific literature and developed a basic framework by outlining goals of genetic counseling as well as some examples of process variables and outcome variables (Wang, Gonzalez, & Merajver, 2004). In a separate effort, Veach et al. used information elicited from GC experts to develop the Reciprocal Engagement Model (REM) of genetic counseling practice which outlines tenets, goals, strategies, and behaviors relevant to the GC profession along with a few outcomes (Veach, Bartels, & LeRoy, 2007). Efforts to systematically or comprehensively identify important genetic services outcomes have been conducted by several groups. Two groups in the United Kingdom analyzed qualitative patient data and independently defined similar sets of outcomes that are important to patients (Marion McAllister et al., 2007, 2008; Pithara, 2014). One of these groups subsequently developed and validated the Genetic Counseling Outcomes Scale to assess the overarching construct of patient empowerment, defined as “a set of beliefs that enables a person from a family affected by a genetic condition to feel they have some control over and hope for the future” (Mcallister, Wood, Dunn, Shiloh, & Todd, 2011). In the United States (U.S.), the Western States Regional Genetics Collaborative developed a menu of outcomes related to genetic service delivery in clinical and public health settings (Silvey, Stock, Hasegawa, & Au, 2009). In another effort, a multidisciplinary group of health care professionals from the U.S. and United Kingdom identified and prioritized a set of “quality indicators” for clinical genetics (Zellerino, Milligan, Gray, Williams, & Brooks, 2009). Based on a literature review of outcome measures, a group in the United Kingdom identified 19 key domains captured by genetic service outcomes measures and asked patients and providers to determine which are most appropriate to measure (Payne, Nicholls, McAllister, Macleod, et al., 2007; Payne, Nicholls, McAllister, MacLeod, et al., 2007). Most recently, work by U.S. researchers in collaboration with a National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) sub-committee has generated outcomes specific to genetic counseling sessions (Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2015; Zierhut, Shannon, Cragun, & Cohen, 2016).

Recognizing the need to cohesively synthesize prior efforts, our initial aim was to develop a framework that: 1) organizes, consolidates, and conceptualizes clinical outcomes; 2) postulates how these outcomes connect to GC skills and processes that can be combined to form an overall communication strategy; and 3) aligns framework components with possible measures that have previously or could be used in conducting genetic counseling outcomes research. The framework intentionally concentrates on clinical communication services in GC and does not encompass other medical aspects of genetic service delivery which were outside the scope of this project. In this paper we describe framework development and the creation of a website prototype to house information about the framework. We also illustrate how to tailor the framework for practical use in considering genetic counseling-specific outcomes using a step-by-step guide. Finally, we discuss future directions for using and refining the framework and how it may help in gathering an evidence base for defining quality in genetic counseling.

METHODS

Overview of Framework Development and “Outcomes” Categorization

Models, theories and frameworks are all tools for conceptualizing, evaluating, and understanding phenomena; and distinctions between these three terms are not critical for our purposes. Terminology for the components of a framework can vary, but we use the terms constructs (abstract ideas or concepts) and domains (groupings of similar or related constructs).

In developing the framework we drew upon our collective training and experience related to: 1) clinical genetic counseling practice and research; 2) existing behavioral or communication models and published literature from several targeted reviews; and 3) a list of nearly 200 outcomes generated as part of prior and ongoing efforts to elicit GC outcomes (Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2015). We began by grouping the list of “outcomes” into broad domains using a modified logic model approach beginning with the most distal patient outcomes and working backwards toward “outcomes” that would be more directly influenced by GC (Kenyon, Palakshappa, & Feudtner, 2015). An initial attempt to further categorize and consolidate these was taken by the first author and then audited by the other author. Discrepancies in categorization and in domain and construct labels were discussed until a consensus was reached between authors. Framework development was iterative and involved weekly discussions between the authors over a period of approximately two years, with additional revisions over the course of several months.

Early in our process we defined several framework domains. The first, which we ultimately called “patient health”, reflects changes in patients’ mental, physical, or social health that are hypothesized to be indirectly influenced by genetic counseling. We then worked backwards to propose how genetic counseling might mediate (i.e., influence or lead to) patient health. Using the “Direct and Indirect Pathways from Communication to Health Outcomes ” model (Street, 2013; Street & Epstein, 2007; Street et al., 2009), Wang’s framework for evaluating genetic services (Wang et al., 2004), Donabedian’s Model of Quality Care (Donabedian, 1988), and the National Quality Measures Clearninghouse (“National Quality Measures Clearninghouse,” 2017) to guide our efforts, we defined three additional domains, which we ultimately called:“process measures”; “patient care experience”; and “patient changes”. We also added a “family changes” domain to reflect findings that genetic services can impact outcomes for other family members (Marion McAllister et al., 2007; Payne, Nicholls, McAllister, MacLeod, et al., 2007). During this process we further categorized and recategorized “outcomes” using thematic analysis and then defined constructs using emergent themes and prior work by other researchers (Mcallister et al., 2011; Nci et al., 2007; Payne, Nicholls, McAllister, MacLeod, et al., 2007; Pithara, 2014; Silvey et al., 2009; Street, 2013; Wang et al., 2004). We also added constructs from several widely used theories or frameworks such as the Health Belief Model, Theory of Planned Behavior, Self-determination Theory, and Extended Parallel Process Model, (DiClemente, Crosby, & Kegler, 2009; Glanz & Bishop, 2010; Witte, 1992). To preserve parsimony in an already complex framework, we combined constructs we deemed to have substantial overlap and selected or created labels we agreed were most descriptive of blended or newly created constructs.

Linking “Outcomes” to Communication Skills and Processes

When considering how genetic counseling might influence various outcomes, we extracted several lists of behaviors, techniques, processes, and communication functions from the REM (Veach et al., 2007), GC competencies (Accreditation Counsel for Genetic Counseling, 2015), framework for evaluating genetic services (Wang et al., 2004), Direct and Indirect Pathways to Patient Outcomes model (Nci et al., 2007; Street, 2013; Street et al., 2009), Social Support Theory (House, 1981), Motivational Interviewing (Lundahl et al., 2013; Miller & Rollnick, 2013), Self-determination Theory (SDT) (DiClemente et al., 2009), the Ottowa Decision Making Framework (Légaré et al., 2006), GC research (Hallowell, Lawton, & Gregory, 2005; Lerner, Li, Valdesolo, & Kassam, 2015; Bettina Meiser, Irle, Lobb, & Barlow-Stewart, 2008; Roter, Ellington, Erby, Larson, & Dudley, 2006), and widely used GC texts (Hartmann, Veach, MacFarlane, & LeRoy, 2015; Uhlmann, Schuette, & Yashar, 2009; Veach, LeRoy, & Bartels, 2010, 2003). Using a similar iterative approach used to organize outcomes, we categorized items on these lists using thematic analysis and then consolidated them into communication skills categories that are each comprised of several communication processes.

Our approach to link outcomes with communication skills and processes was largely influenced by the REM (Veach et al., 2007) and Direct and Indirect Pathways to Patient Outcomes model (Hoerger et al., 2013; Nci et al., 2007; Street, 2013; Street et al., 2009). Through co-opting, blending, and modifying visual representations of patient-centered communication illustrated by Hoerger et al. (Hoerger et al., 2013) and Street (Street, 2013; Street et al., 2009), we depicted the following framework components: 1) influence of patient and provider goals; 2) skills and processes that comprise a communication strategy; 3) reciprocal communication that occurs between genetic service providers and patients, which is central to the REM; and 4) possible links by which hypothesized strategies may improve the patient care experience and lead to desired cognitive, emotional, or behavioral changes in patients or their family members.

Considering Context

To complete the framework, we followed Epstein and Street’s recommendation to consider the important influence of individual-, family-, cultural-, institutional-, or policy-level factors that may influence patient outcomes (Nci et al., 2007). Examples of these include; sociodemographics of both the patient and genetic service provider as well as disease-related factors, patient’s illness representation, health literacy and numeracy, family structure, social distance from family members, health insurance status and type, social support, cultural context, policies, laws, health care system factors, and provider self-awareness. Although contextual factors could mediate or moderate proposed relationships between many of the framework constructs, these are external to the main framework domains.

Creation of a Website, Concrete Examples, and Step-by-step Guide

Due to the large amount of content in the framework and the foreseeable need to continue making ongoing modifications or updates, an on-line website was created under the domain https://www.focusoutcomes.com/. The website was designed to assist in disseminating the framework and to help people navigate framework content while minimizing the likelihood they will be overwhelmed with too much information at one time. Concrete examples were created to illustrate how components of the framework can be combined in different ways to illustrate different outcomes. Finally, a step-by-step guide was also created to help demonstrate one way in which the framework can be used to develop a plan for evaluating genetic counseling services or conducting a research study.

RESULTS

General framework

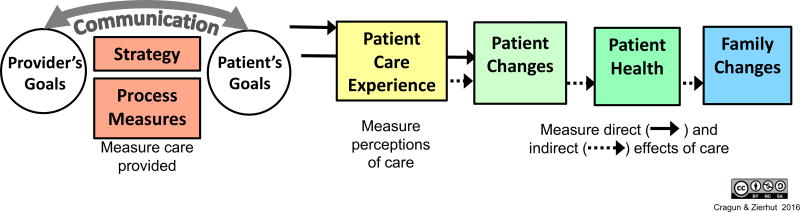

The title we selected, “Framework for outcomes of clinical communication services (FOCUS),” reflects the framework’s general purposes which are to: 1) organize and consolidate outcomes to help researchers and health care providers select and focus on outcome(s) they are interested in evaluating; 2) hypothesize how the outcomes may relate to each other and to various skills and processes that may be employed as part of a communication strategy in clinical settings; and 3) align framework components with possible measures. The general relationships between domains that comprise FOCUS and patient and provider goals are depicted in Figure 1. FOCUS domains include: 1) communication strategy (i.e., the overall combination of skills and processes employed to achieve the goals); 2) communication process measures; 3) patient care experience; 4) patient changes; 5) patient health; and 6) family changes. The resulting framework provides clinicians and researchers with flexibility to combine communication skills in various ways in order to design a strategy hypothesized to achieve specific outcomes of interest.

Figure 1.

Framework for Outcomes in Clinical Communication Services (FOCUS)

Patient and provider goals within the context of genetic counseling have been described or studied previously by other researchers (Bernhardt, Biesecker, & Mastromarino, 2000; Hartmann et al., 2015; Peters & Petrill, 2011; Veach et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2004). Our targeted literature review revealed that goals vary from patient to patient in different subspecialty settings (Peters & Petrill, 2011) and many patients are unaware of what to expect from genetic counseling and therefore lack well-defined goals (Bernhardt et al., 2000). Genetic counseling goals from the REM fall into four main categories: 1) understanding and appreciation; 2) support and guidance; 3) facilitative decision-making; and 4) patient-centered education (Hartmann et al., 2015). These goals are similar to the three overarching goals of genetic counseling described by Wang et al., which include: 1) educate and inform, 2) provide support and help cope, and 3) facilitate informed decision-making (Wang et al., 2004).

A communication strategy is a plan or method for achieving patient and provider goals and positively influencing patient care experiences, changes, and/or health. A strategy can be created by combining various communication skills and processes that are categorized in Table 1a. Communication process measures reflect the clinical communication services that take place. Processes can be measured using checklists, chart reviews, or third-party observation to document use of communication skills, adherence to professional guidelines, patients’ level of involvement, and other components of care. Constructs within the communication process domain and some example measures that may assess these constructs are listed in Table 1b.

Table 1.

| a. Communication Skills Used to Create Strategies as part of the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Communication skills categoriesa |

Description of skills and processes | Hypothesized to influence patient experience, changes and health |

| Building rapport (i.e., establishing a professional relationship and mutual respect) [1, 5–7, 10] |

|

|

| Mutual agenda setting (i.e., contracting) [1–4] |

|

|

| Gathering medical and psychosocial information |

|

|

| Responding to emotions [1, 3–7, 9, 11, 14–16] |

|

|

| Educating and checking for understanding [1, 2, 5–8] |

|

|

| Communicating risk [3, 4, 8, 9] |

|

|

| Communication framing and format [10–13] |

|

|

| Mobilizing patient strengths, resources, support [1, 4, 8, 9, 15] |

|

|

| Engaging patient in decision making [1, 3, 4, 7, 10, 11, 15, 16, 18] |

|

|

| Supporting patient autonomy [1, 9, 11, 16–18] |

|

|

| Action planning [15–18] |

|

|

| Skill-building [8, 10, 11, 15] |

|

|

| Care coordination and provision of resources [19] |

|

|

| b. Communication Process Measures from the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Categories of Communication Process Measuresa |

Description | Example Measuresb |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Communication skills can be combined to create a strategy for achieving patient and provider goals and positively influencing patient experiences, patient changes, patient health, and/or family changes.

References

P. M. Veach, D. M. Bartels, and B. S. Leroy, “Coming full circle: a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice.,” J. Genet. Couns., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 713–28, Dec. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17934802

M. Hoerger, R. M. Epstein, P. C. Winters, K. Fiscella, P. R. Duberstein, R. Gramling, P. N. Butow, S. G. Mohile, P. R. Kaesberg, W. Tang, S. Plumb, A. Walczak, A. L. Back, D. Tancredi, A. Venuti, C. Cipri, G. Escalera, C. Ferro, D. Gaudion, B. Hoh, B. Leatherwood, L. Lewis, M. Robinson, P. Sullivan, and R. L. Kravitz, “Values and options in cancer care (VOICE): study design and rationale for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers.,” BMC Cancer, vol. 13, p. 188, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23570278

W. R. Uhlmann, J. L. Schuette, and B. M. Yashar, A guide to genetic counseling, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

P. M. Veach, B. S. LeRoy, and D. M. Bartels, Facilitating the genetic counseling process: a practice manual. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2003.

R. L. Street, G. Makoul, N. K. Arora, and R. M. Epstein, “How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 295–301, Mar. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19150199

R. L. Street, “How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 286–91, Sep. 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23746769

R. L. Street and R. M. Epstein, Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication, 2007. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pcc_monograph.pdf

T. T. Ha Dinh, A. Bonner, R. Clark, J. Ramsbotham, and S. Hines, “The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: a systematic review.,” JBI database Syst. Rev. Implement. reports, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 210–47, Jan. 2016. https://ww w.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26878928

Accreditation Counsel for Genetic Counseling, “Practice-Based Competencies for Genetic Counselors Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling,” 2015. http://www.gceducation.org/Documents/ACGC Core Competencies Brochure_15_Web.pdf

P. M. Veach, B. LeRoy, and D. M. Bartels, Genetic counseling practice : advanced concepts and skills. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

J. Weil, Psychosocial genetic counseling, 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000.

D. Kirklin, “Framing, truth telling and the problem with non-directive counselling.,” J. Med. Ethics, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 58–62, Jan. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17209114

M. W. Kreuter, M. C. Green, J. N. Cappella, M. D. Slater, M. E. Wise, D. Storey, E. M. Clark, D. J. O’Keefe, D. O. Erwin, K. Holmes, L. J. Hinyard, T. Houston, and S. Woolley, “Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: a framework to guide research and application.,” Ann. Behav. Med., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 221–35, Jun. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17600449

K. J. McCaffery, M. Holmes-Rovner, S. K. Smith, D. Rovner, D. Nutbeam, M. L. Clayman, K. Kelly-Blake, M. S. Wolf, and S. L. Sheridan, “Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids.,” BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak., vol. 13 Suppl 2, p. S10, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24624970

C. Wang, R. Gonzalez, and S. D. S. D. Merajver, “Assessment of genetic testing and related counseling services: current research and future directions.,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 1427–42, Apr. 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14759687

R. J. DiClemente, R. A. Crosby, and M. Kegler, Emerging theories in health promotion pracitce and research, 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2009.

W. R. Miller and S. Rollnick, Motivational interviewing: helping people change, 3rd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, 2013.

A. Murray, A. M. Hall, G. C. Williams, S. M. McDonough, N. Ntoumanis, I. M. Taylor, B. Jackson, J. Matthews, D. A. Hurley, and C. Lonsdale, “Effect of a self-determination theory-based communication skills training program on physiotherapists’ psychological support for their patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial.,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 96, no. 5, pp. 809–16, May 2015. https://ww w.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25433220

J. S. House, Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Pub Co., 1981.

Communication process measures, in general, reflect the healthcare services provided to a patient (including what occurred during the communication process and whether strategies were implemented as originally prescribed or intended). Several process measures are expected to influence patient care experiences and may contribute to other changes.

Types of process measures include: checklists, chart reviews, observer coding documenting use of communication strategies, and adherence to professional guidelines. Measures can be based on coding by a third party observer during or after the visit (if it is audio recorded) or through medical record checklists completed by providers.

References

C. G. Shields, P. Franks, K. Fiscella, S. Meldrum, and R. M. Epstein, “Rochester Participatory Decision-Making Scale (RPAD): reliability and validity.,” Ann. Fam. Med., vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 436–42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16189060

C. H. Braddock, K. A. Edwards, N. M. Hasenberg, T. L. Laidley, and W. Levinson, “Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics.,” JAMA, vol. 282, no. 24, pp. 2313–20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10612318

C. L. Bylund and G. Makoul, “Empathic communication and gender in the physician-patient encounter.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 48, no. 3, pp. 207–16, Dec. 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12477605

D. Roter and S. Larson, “The Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 46, no. 4, pp. 243–51, Apr. 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11932123

H. S. Gordon, R. L. Street, B. F. Sharf, and J. Souchek, “Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation.,” Cancer, vol. 107, no. 6, pp. 1313–20, Sep. 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16909424

R. E. Glasgow, S. Emont, and D. C. Miller, “Assessing delivery of the five ‘As’ for patient-centered counseling.,” Health Promot. Int., vol. 21, no. 3, pp. 245–55, Sep. 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16751630

T. Kettunen, L. Liimatainen, J. Villberg, and U. Perko, “Developing empowering health counseling measurement. Preliminary results.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 64, no. 1–3, pp. 159–66, Dec. 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16469473

K. Payne, S. G. Nicholls, M. McAllister, R. MacLeod, I. Ellis, D. Donnai, and L. M. Davies, “Outcome measures for clinical genetics services: a comparison of genetics healthcare professionals and patients’ views.,” Health Policy, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 112–22, Nov. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17485130

B. R. Cassileth, R. V Zupkis, K. Sutton-Smith, and V. March, “Information and participation preferences among cancer patients.,” Ann. Intern. Med., vol. 92, no. 6, pp. 832–6, Jun. 1980. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7387025

C. G. Blanchard, M. S. Labrecque, J. C. Ruckdeschel, and E. B. Blanchard, “Information and decision-making preferences of hospitalized adult cancer patients.,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 1139–45, 1988. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3206248

R. L. Street, D. Cauthen, E. Buchwald, and R. Wiprud, “Patients’ predispositions to discuss health issues affecting quality of life.,” Fam. Med., vol. 27, no. 10, pp. 663–70. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8582560

R. G. Hagerty, P. N. Butow, P. A. Ellis, E. A. Lobb, S. Pendlebury, N. Leighl, D. Goldstein, S. K. Lo, and M. H. N. Tattersall, “Cancer patient preferences for communication of prognosis in the metastatic setting.,” J. Clin. Oncol., vol. 22, no. 9, pp. 1721–30, May 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15117995

R. L. Street and R. M. Epstein, Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication, 2007. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pcc_monograph.pdf

R. L. Street and B. Millay, “Analyzing Patient Participation in Medical Encounters,” Health Commun., vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 61–73, Jan. 2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11370924

W. R. Miller, T. B. Moyers, D. Ernst, and P. Amrhein, “Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC),” 2008. [Online]. Available: http://casaa.unm.edu/download/misc.pdf.

K. M. McDonald, E. Schultz, L. Albin, N. Pineda, J. Lonhart, V. Sundaram, C. Smith-Spangler, J. Brunstrom, E. Malcolm, L. Rohn, and S. Davies, “Care Coordination Measures Atlas Update,” 2014. [Online]. Available: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/prevention-chronic-care/improve/coordination/atlas2014/index.html.

P. M. Veach, D. M. Bartels, and B. S. Leroy, “Coming full circle: a reciprocal-engagement model of genetic counseling practice.,” J. Genet. Couns., vol. 16, no. 6, pp. 713–28, Dec. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17934802

K. Silvey, J. Stock, L. E. Hasegawa, and S. M. Au, “Outcomes of genetics services: creating an inclusive definition and outcomes menu for public health and clinical genetics services.,” Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet., vol. 151C, no. 3, pp. 207–13, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19621453

Accreditation Counsel for Genetic Counseling, “Practice-Based Competencies for Genetic Counselors Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling,” 2015. http://www.gceducation.org/Documents/ACGC Core Competencies Brochure_15_Web.pdf

R. L. Bennett, K. A. Steinhaus, S. B. Uhrich, C. K. O’Sullivan, R. G. Resta, D. Lochner-Doyle, D. S. Markel, V. Vincent, and J. Hamanishi, “Recommendations for standardized human pedigree nomenclature. Pedigree Standardization Task Force of the National Society of Genetic Counselors.,” Am. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 56, no. 3, pp. 745–52, Mar. 1995. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7887430

Patient care experiences consist of different types of feedback from patients and their families or caregivers about the delivery of patient care. Some of the examples listed in Table 2 include: meeting patient needs, perceptions of the patient/provider relationship, perceptions of communication, and perceptions of information received. These reflect the level of patient-centered care and may influence other downstream changes.

Table 2.

Patient Care Experience from the Framework for Outcomes of Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS)

| Patient Care Experience Categoriesa |

Description | Example measures | Hypothesized to influence other outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Patient experience measures reflect patient-centeredness which is one of the six quality health domains

Although more specific, these categories may encompass some aspects of what people have referred to as “patient satisfaction”.

References

C. Wang, R. Gonzalez, and S. D. S. D. Merajver, “Assessment of genetic testing and related counseling services: current research and future directions.,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 58, no. 7, pp. 1427–42, Apr. 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14759687

T. A. DeMarco, B. N. Peshkin, B. D. Mars, and K. P. Tercyak, “Patient satisfaction with cancer genetic counseling: a psychometric analysis of the Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale.,” J. Genet. Couns., vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 293–304, Aug. 2004. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19736695

S. Shiloh, O. Avdor, and R. M. Goodman, “Satisfaction with genetic counseling: Dimensions and measurement,” Am. J. Med. Genet., vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 522–529, Dec. 1990. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajmg.1320370419/abstract;jsessionid=0D869F79210E85EC865859AE4B3F00A8.f03t02

C. E. Lerman, D. S. Brody, G. C. Caputo, D. G. Smith, C. G. Lazaro, and H. G. Wolfson, “Patients’ Perceived Involvement in Care Scale: relationship to attitudes about illness and medical care.,” J. Gen. Intern. Med., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 29–33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2299426

R. L. Street, G. Makoul, N. K. Arora, and R. M. Epstein, “How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 295–301, Mar. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19150199

R. L. Street, “How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 286–91, Sep. 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23746769

R. L. Street and R. M. Epstein, Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication, 2007. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pcc_monograph.pdf

J. P. Galassi, R. Schanberg, and W. B. Ware, “The Patient Reactions Assessment: A brief measure of the quality of the patient-provider medical relationship.,” Psychol. Assess., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 346–351, 1992. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/1040-3590.4.3.346

D. Zohar, Y. Livne, O. Tenne-Gazit, H. Admi, and Y. Donchin, “Healthcare climate: a framework for measuring and improving patient safety.,” Crit. Care Med., vol. 35, no. 5, pp. 1312–7, May 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17414090

Patient changes are cognitive, emotional or behavioral factors that change during or after the visit with the healthcare provider as a direct or indirect result of the care they received. These are listed in table 3 along with a few examples of possible measures that have or could possibly be used to measure these changes.

Table 3.

Patient Changes from the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS)

| Patient Change Categoriesa |

Description | Example measures | Hypothesized relationships with other patient changes, patient experiences, or health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Patient changes are factors that change as a direct or indirect result of health services received. These are expected to influence patient health outcomes and/or family changes.

This encompasses the concept of “understanding” from Pithara [8] and McAllister’s concept of “cognitive control” [27]. This term also encompasses aspects of “perceived personal control” [15]. Lastly, it is also the inverse of feeling uninformed, which is a component of “decisional conflict” [16].

Inclusive of Pithera’s concept of “informed and shared decision making”[8] as well as McAllister’s concept of “decisional regulation” [27]. This term also encompasses aspects of perceived personal control [15] and decisional self-efficacy [28]. Finally, this construct is the inverse of several components of “decisional conflict” [16].

Inclusive of Pithara’s concept of “enablement” [8] and McAllister’s concept “behavioral control” [27]. This term also encompasses aspects of “perceived personal control” [15] and “behavioral self-efficacy”[28].

Inclusive of Pithera’s concept “reassurance” [8] and McAllister’s concept “emotional regulation” [27]. It is also similar to “emotional self-efficacy” [28].

References

N. Ondrusek, E. Warner, and V. Goel, “Development of a knowledge scale about breast cancer and heredity (BCHK).,” Breast Cancer Res. Treat., vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 69–75, Jan. 1999.

C. Lerman, B. Biesecker, J. L. Benkendorf, J. Kerner, A. Gomez-Caminero, C. Hughes, and M. M. Reed, “Controlled trial of pretest education approaches to enhance informed decision-making for BRCA1 gene testing.,” J. Natl. Cancer Inst., vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 148–57, Jan. 1997.

J. Erblich, K. Brown, Y. Kim, H. B. Valdimarsdottir, B. E. Livingston, and D. H. Bovbjerg, “Development and validation of a Breast Cancer Genetic Counseling Knowledge Questionnaire.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 182–91, Feb. 2005.

S. A. Bannon, M. Mork, E. Vilar, S. K. Peterson, K. Lu, P. M. Lynch, M. A. Rodriguez-Bigas, Y. N. You, V. Bonadona, B. Bonaiti, S. Olschwang, S. Grandjouan, L. Huiart, M. Longy, R. Guimbaud, B. Buecher, Y. Bignon, O. Caron, E. Stoffel, B. Mukherjee, V. Raymond, N. Tayob, F. Kastrinos, J. Sparr, F. Wang, P. Bandipalliam, S. Syngal, S. Gruber, A. Win, N. Lindor, J. Young, F. Macrae, G. Young, E. Williamson, S. Parry, J. Goldblatt, L. Lipton, I. Winship, L. Capelle, N. Van Grieken, H. Lingsma, E. Steyerberg, W. Klokman, M. Bruno, H. Vasen, E. Kuipers, S. Weissman, C. Bellcross, C. Bittner, M. Freivogel, J. Haidle, P. Kaurah, A. Leininger, S. Palaniappan, K. Steenblock, T. Vu, M. Daniels, N. Lindor, G. Petersen, D. Hadley, A. Kinney, S. Miesfeldt, K. Lu, P. Lynch, W. Burke, N. Press, E. Stoffel, J. Garber, S. Grover, L. Russo, J. Johnson, S. Syngal, Z. Ketabi, B. Mosgaard, A. Gerdes, S. Ladelund, I. Bernstein, K. Metcalfe, D. Birenbaum-Carmeli, J. Lubinski, J. Gronwald, H. Lynch, P. Moller, P. Ghadirian, W. Foulkes, J. Klijn, E. Friedman, R. Battista, I. Blancquaert, A. Laberge, N. van Schendel, N. Leduc, A. Hawkins, M. Hayden, C. Espenschied, D. MacDonald, J. Culver, S. Sand, K. Hurley, K. Banks, J. Weitzel, K. Blazer, A. Nolen, and J. Putten, “Patient-reported disease knowledge and educational needs in Lynch syndrome: findings of an interactive multidisciplinary patient conference,” Hered. Cancer Clin. Pract., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 1, Dec. 2014.

Y.-L. Lee, D.-T. Lin, and S.-F. Tsai, “Disease knowledge and treatment adherence among patients with thalassemia major and their mothers in Taiwan.,” J. Clin. Nurs., vol. 18, no. 4, pp. 529–38, Feb. 2009.

A. G. Ames, A. Jaques, O. C. Ukoumunne, A. D. Archibald, R. E. Duncan, J. Emery, and S. A. Metcalfe, “Development of a fragile X syndrome (FXS) knowledge scale: towards a modified multidimensional measure of informed choice for FXS population carrier screening.,” Health Expect., vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 69–80, Feb. 2015.

V. Goel, R. Glazier, S. Holzapfel, P. Pugh, and A. Summers, “Evaluating patient’s knowledge of maternal serum screening.,” Prenat. Diagn., vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 425–30, May 1996.

C. Pithara, “Identifying outcomes of clinical genetic services: qualitative evidence and methodological considerations.,” J. Genet. Couns., vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 229–38, Apr. 2014.

K. Payne, S. G. Nicholls, M. McAllister, R. MacLeod, I. Ellis, D. Donnai, and L. M. Davies, “Outcome measures for clinical genetics services: a comparison of genetics healthcare professionals and patients’ views.,” Health Policy, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 112–22, Nov. 2007.

M. Mcallister, A. Wood, G. Dunn, S. Shiloh, and C. Todd, “The Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale: A new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services,” Clin. Genet., vol. 79, pp. 413–424, 2011.

R. L. Street, G. Makoul, N. K. Arora, and R. M. Epstein, “How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 295–301, Mar. 2009.

R. L. Street, “How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 286–91, Sep. 2013.

R. L. Street and R. M. Epstein, Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication, 2007.

M. McAllister, G. Dunn, and C. Todd, “Empowerment: qualitative underpinning of a new clinical genetics-specific patient-reported outcome.,” Eur. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 125–30, Feb. 2011.

M. Berkenstadt, S. Shiloh, G. Barkai, M. B. Katznelson, and B. Goldman, “Perceived personal control (PPC): a new concept in measuring outcome of genetic counseling.,” Am. J. Med. Genet., vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 53–9, Jan. 1999.

M. C. Katapodi, M. L. Munro, P. F. Pierce, and R. A. Williams, “Psychometric testing of the decisional conflict scale: genetic testing hereditary breast and ovarian cancer.,” Nurs. Res., vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 368–77.

“Decisional Conflict Scale,” The Ottawa Hospital, 2015..

A. M. O’Connor, “Validation of a decisional conflict scale.,” Med. Decis. Making, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 25–30.

J. Cockburn, P. Fahey, and R. W. Sanson-Fisher, “Construction and validation of a questionnaire to measure the health beliefs of general practice patients.,” Fam. Pract., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 108–16, Jun. 1987.

K. Witte, K. A. Cameron, J. K. McKeon, and J. M. Berkowitz, “Predicting risk behaviors: development and validation of a diagnostic scale.,” J. Health Commun., vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 317–41, 1996.

R. S. Lazarus and S. Folkman, “Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping,” Eur. J. Pers., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 141–169, Sep. 1987.

M. H. Mishel, “The measurement of uncertainty in illness.,” Nurs. Res., vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 258–63.

L. Lin, A. A. Acquaye, E. Vera-Bolanos, J. E. Cahill, M. R. Gilbert, and T. S. Armstrong, “Validation of the Mishel’s uncertainty in illness scale-brain tumor form (MUIS-BT).,” J. Neurooncol., vol. 110, no. 2, pp. 293–300, Nov. 2012.

I. Ajzen, “TPB Questionnaire Construction 1 CONSTRUCTING A THEORY OF PLANNED BEHAVIOR QUESTIONNAIRE.”

Self-Determination Theory, “Questionnaires,” 2016..

R. W. Lent and S. D. Brown, “On Conceptualizing and Assessing Social Cognitive Constructs in Career Research: A Measurement Guide,” J. Career Assess., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 12–35, Feb. 2006.

M. McAllister, K. Payne, R. Macleod, S. Nicholls, Dian Donnai, and L. Davies, “Patient empowerment in clinical genetics services.,” J. Health Psychol., vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 895–905, Oct. 2008.

A. Bandura, Self-efficacy: the exercise of control, 1st ed. W.H. Freeman & company, 1997.

A. Ferron Parayre, M. Labrecque, M. Rousseau, S. Turcotte, and F. Légaré, “Validation of SURE, a four-item clinical checklist for detecting decisional conflict in patients.,” Med. Decis. Making, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 54–62, Jan. 2014.

“Self-Determination Theory,” sdt..

K. Silvey, J. Stock, L. E. Hasegawa, and S. M. Au, “Outcomes of genetics services: creating an inclusive definition and outcomes menu for public health and clinical genetics services.,” Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet., vol. 151C, no. 3, pp. 207–13, Aug. 2009.

“Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease 6-Item Scale,” Stanford Patient Education Research Center..

K. M. Abraham, C. J. Miller, D. G. Birgenheir, Z. Lai, and A. M. Kilbourne, “Self-efficacy and quality of life among people with bipolar disorder.,” J. Nerv. Ment. Dis., vol. 202, no. 8, pp. 583–8, Aug. 2014.

PROMIS, “EMOTIONAL SUPPORT ABOUT EMOTIONAL SUPPORT,” 2015.

PROMIS, “INFORMATIONAL SUPPORT,” 2015.

PROMIS, “INSTRUMENTAL SUPPORT,” 2015.

PROMIS, “SELF-EFFICACY FOR MANAGING CHRONIC CONDITIONS A Brief Guide to the PROMIS Self-Efficacy Instruments,” 2015.

B. A. Kirk, N. S. Schutte, and D. W. Hine, “Development and preliminary validation of an emotional self-efficacy scale,” Pers. Individ. Dif., vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 432–436, 2008.

K. Glanz and D. B. Bishop, “The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions.,” Annu. Rev. Public Health, vol. 31, pp. 399–418, 2010.

C. Wang, R. Gonzalez, and S. D. S. D. Merajver, “Assessment of genetic testing and related counseling services: current research and future directions.,” Soc. Sci. Med., vol. 58, pp. 1427–1442, 2004.

S. W. Vernon, E. R. Gritz, S. K. Peterson, C. A. Perz, S. Marani, C. I. Amos, and W. F. Baile, “Intention to learn results of genetic testing for hereditary colon cancer.,” Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., vol. 8, no. 4 Pt 2, pp. 353–60, Apr. 1999.

S. Michie, E. Dormandy, and T. M. Marteau, “The multi-dimensional measure of informed choice: a validation study.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 48, no. 1, pp. 87–91, Sep. 2002.

J. C. Brehaut, A. M. O’Connor, T. J. Wood, T. F. Hack, L. Siminoff, E. Gordon, and D. Feldman-Stewart, “Validation of a decision regret scale.,” Med. Decis. Making, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 281–92.

J. McLaughlin and E. M. Sliepcevich, “The self-care behavior inventory: a model for behavioral instrument development.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 289–301, Sep. 1985.

S. Rutherford, X. Zhang, C. Atzinger, J. Ruschman, and M. F. Myers, “Medical management adherence as an outcome of genetic counseling in a pediatric setting.,” Genet. Med., vol. 16, pp. 157–63, 2014.

J. S. House, Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Pub Co., 1981.

M. Horowitz, N. Wilner, and W. Alvarez, “Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress.,” Psychosom. Med., vol. 41, no. 3, pp. 209–18, May 1979.

D. Cella, C. Hughes, A. Peterman, C.-H. Chang, B. N. Peshkin, M. D. Schwartz, L. Wenzel, A. Lemke, A. C. Marcus, and C. Lerman, “A brief assessment of concerns associated with genetic testing for cancer: the Multidimensional Impact of Cancer Risk Assessment (MICRA) questionnaire.,” Health Psychol., vol. 21, no. 6, pp. 564–72, Nov. 2002.

B. B. Biesecker and L. Erby, “Adaptation to living with a genetic condition or risk: a mini-review.,” Clin. Genet., vol. 74, no. 5, pp. 401–7, Nov. 2008.

L. Folkman, “WAYS OF COPING.”

S. Folkman and R. Lazarus, “Ways of Coping Questionnaire,” Consulting Psychologists Press, 1988..

Patient health includes both objective and patient reported changes in mental, physical, or social health that result from the clinical care received. In the case of clinical communication services, changes in patient health are more likely to occur indirectly as the result of upstream influences services may have on patient care experiences or patient changes. Patient health outcomes are listed in Table 4 along with some measures to serve as examples.

Table 4.

Patient Health Outcomes from the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS)

| Patient Health Outcome Categoriesa |

Description (examples of relationship to patient changes) |

Example Measuresb |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

Patient Health Outcomes include changes in health and well-being that occur as a direct or indirect result of receiving health services.

Measures are often patient reported, but can be performance-based measures, caregiver/proxy reported or direct observation.

Patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) has many assessment measures that reflect patient-reported health. These are calibrated item banks or scales, item pools or short forms http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/InstrumentsAvailable_11516_508.pdf

References

R. L. Street, G. Makoul, N. K. Arora, and R. M. Epstein, “How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician-patient communication to health outcomes.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 74, no. 3, pp. 295–301, Mar. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19150199

R. L. Street, “How clinician-patient communication contributes to health improvement: modeling pathways from talk to outcome.,” Patient Educ. Couns., vol. 92, no. 3, pp. 286–91, Sep. 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23746769

R. L. Street and R. M. Epstein, Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication, 2007. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/areas/pcc/communication/pcc_monograph.pdf

“Measures of Cancer Survival,” National Cancer Institute. [Online]. Available: http://surveillance.cancer.gov/survival/measures.html.

L. Renkonen-Sinisalo, M. Aarnio, J. P. Mecklin, and H. J. Järvinen, “Surveillance improves survival of colorectal cancer in patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer.,” Cancer Detect. Prev., vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 137–42, 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10917133

R. Schulz, J. K. Monin, S. J. Czaja, J. H. Lingler, S. R. Beach, L. M. Martire, A. Dodds, R. S. Hebert, B. Zdaniuk, and T. B. Cook, “Measuring the experience and perception of suffering.,” Gerontologist, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 774–84, Dec. 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20478899

D. A. Revicki and K. F. Cook, “PROMIS Pain-Related Measures: An Overview,” 2015. [Online]. Available: http://www.practicalpainmanagement.com/resources/clinical-practice-guidelines/promis-pain-related-measures-overview.

L. Yu, D. J. Buysse, A. Germain, D. E. Moul, A. Stover, N. E. Dodds, K. L. Johnston, and P. A. Pilkonis, “Development of short forms from the PROMIS™ sleep disturbance and Sleep-Related Impairment item banks.,” Behav. Sleep Med., vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 6–24, Dec. 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22250775

“Health-Related Quality of Life and Well-Being,” Healthy People. [Online]. Available: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/about/foundation-health-measures/Health-Related-Quality-of-Life-and-Well-Being.

K. D. M. Ruijs, B. D. Onwuteaka-Philipsen, G. van der Wal, and A. J. F. M. Kerkhof, “Unbearability of suffering at the end of life: the development of a new measuring device, the SOS-V.,” BMC Palliat. Care, vol. 8, p. 16, 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19887004

PROMIS, “PHYSICAL FUNCTION,” 2015. https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS Physical Function Scoring Manual.pdf

J. E. Brazier, R. Harper, N. M. Jones, A. O’Cathain, K. J. Thomas, T. Usherwood, and L. Westlake, “Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care.,” BMJ, vol. 305, no. 6846, pp. 160–4, Jul. 1992. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1285753

I. H. M. Aas, “Guidelines for rating Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF).,” Ann. Gen. Psychiatry, vol. 10, p. 2, 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21251305

PROMIS, “Sexual Function and Satisfaction Measures User Manual,” 2015. https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/Sexual Function Manual.pdf

PROMIS, “Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities,” 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.nihpromis.com/Science/PubsDomain/Socialroles_part.aspx?AspxAutoDetectCookieSupport=1.

PROMIS, “Social Support,” 2016. [Online]. Available: http://www.nihpromis.com/science/PubsDomain/Social_support.

PROMIS, “SOCIAL ISOLATION,” 2015. https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS Social Isolation Scoring Manual.pdf

K. Silvey, J. Stock, L. E. Hasegawa, and S. M. Au, “Outcomes of genetics services: creating an inclusive definition and outcomes menu for public health and clinical genetics services.,” Am. J. Med. Genet. C. Semin. Med. Genet., vol. 151C, no. 3, pp. 207–13, Aug. 2009. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19621453

T. L. Patterson and B. T. Mausbach, “Measurement of functional capacity: a new approach to understanding functional differences and real-world behavioral adaptation in those with mental illness.,” Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol., vol. 6, pp. 139–54, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20334554

M. McAllister, K. Payne, R. Macleod, S. Nicholls, Dian Donnai, and L. Davies, “Patient empowerment in clinical genetics services.,” J. Health Psychol., vol. 13, no. 7, pp. 895–905, Oct. 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18809640

M. McAllister, G. Dunn, and C. Todd, “Empowerment: qualitative underpinning of a new clinical genetics-specific patient-reported outcome.,” Eur. J. Hum. Genet., vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 125–30, Feb. 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20924407

C. Lo, T. Panday, J. Zeppieri, A. Rydall, P. Murphy-Kane, C. Zimmermann, and G. Rodin, “Preliminary psychometrics of the Existential Distress Scale in patients with advanced cancer.,” Eur. J. Cancer Care (Engl)., Oct. 2016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27778415

U. Ravens-Sieberer, J. Devine, K. Bevans, A. W. Riley, J. Moon, J. M. Salsman, and C. B. Forrest, “Subjective well-being measures for children were developed within the PROMIS project: presentation of first results.,” J. Clin. Epidemiol., vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 207–18, Feb. 2014. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24295987

PROMIS, “ANXIETY,” 2015. https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS Anxiety Scoring Manual.pdf

PROMIS, “DEPRESSION,” 2015. https://www.assessmentcenter.net/documents/PROMIS Depression Scoring Manual.pdf

L. J. Julian, “Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A),” Arthritis Care Res. (Hoboken)., vol. 63, no. S11, pp. S467–S472, Nov. 2011. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/acr.20561

“The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI),” American Psychological Association. [Online]. Available: http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/trait-state.aspx.

A. S. Zigmond and R. P. Snaith, “The hospital anxiety and depression scale.,” Acta Psychiatr. Scand., vol. 67, no. 6, pp. 361–70, Jun. 1983. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6880820

P. M. Lewinsohn, J. R. Seeley, R. E. Roberts, and N. B. Allen, “Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults.,” Psychol. Aging, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 277–87, Jun. 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9189988

Family changes consist of factors that change among the patient’s family as an indirect result of health services provided to a patient. These can include: family communication, family functioning, family member access to appropriate care, and caregiver burden detailed in Table 5. Several of these changes may be important contributors to improved health outcomes among family members.

Table 5.

Family Changes from the Framework for Outcomes in Clinical commUnication Services (FOCUS)

| Family Change Categoriesa |

Description | Example Measures |

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Changes among the patient’s family as an indirect result of health services provided to a patient. These are important because they can lead to improved health outcomes among family members.

References

M. McAllister, K. Payne, S. Nicholls, R. MacLeod, D. Donnai, and L. M. Davies, “Improving service evaluation in clinical genetics: identifying effects of genetic diseases on individuals and families.,” J. Genet. Couns., vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 71–83, Feb. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17295055

K. Payne, S. G. Nicholls, M. McAllister, R. MacLeod, I. Ellis, D. Donnai, and L. M. Davies, “Outcome measures for clinical genetics services: a comparison of genetics healthcare professionals and patients’ views.,” Health Policy, vol. 84, no. 1, pp. 112–22, Nov. 2007. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17485130

C. Hughes, C. Lerman, M. Schwartz, B. N. Peshkin, L. Wenzel, S. Narod, C. Corio, K. P. Tercyak, D. Hanna, C. Isaacs, and D. Main, “All in the family: evaluation of the process and content of sisters’ communication about BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic test results.,” Am. J. Med. Genet., vol. 107, no. 2, pp. 143–50, Jan. 2002. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11807889

I. Mesters, H. van den Borne, L. McCormick, J. Pruyn, M. de Boer, and T. Imbos, “Openness to discuss cancer in the nuclear family: scale, development, and validation.,” Psychosom. Med., vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 269–79, 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9178338

K. E. Watkins, C. Y. Way, D. M. Gregory, H. M. LeDrew, V. C. Ludlow, M. J. Esplen, J. J. Dowden, J. E. Cox, G. W. N. Fitzgerald, and P. S. Parfrey, “Development and preliminary testing of the psychosocial adjustment to hereditary diseases scale.,” BMC Psychol., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 7, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25566359

“FACES IV,” Prepare/enrich. [Online]. Available: http://www.facesiv.com/

D. H. Olson, “Circumplex Model VII: validation studies and FACES III.,” Fam. Process, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 337–51, Sep. 1986. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3758310

J. A. Baptist, D. E. Thompson, A. M. Norton, N. R. Hardy, and C. D. Link, “The effects of the interenerational transmission of family emotional processes on conflict styles: the moderating role of attachment,” Am. J. Fam. Ther., no. 40, pp. 56–73, 2012. http://www.buildingrelationships.com/facesiv_studies/baptist.pdf

D. Olson, “Faces IV and the circumplex model: validation study,” J. Marital Fam. Theraop, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 64–80, 2011. http://www.buildingrelationships.com/facesiv_studies/Validation_Study_JMFT_2011.pdf

P. S. Sinicrope, S. W. Vernon, P. M. Diamond, C. A. Patten, S. H. Kelder, K. G. Rabe, and G. M. Petersen, “Development and preliminary validation of the cancer family impact scale for colorectal cancer.,” Genet. Test., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 161–9, Mar. 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18373413

R. D. Hoge, D. A. Andrews, P. Faulkner, and D. Robinson, “The Family Relationship Index: validity data.,” J. Clin. Psychol., vol. 45, no. 6, pp. 897–903, Nov. 1989. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2613899

K. L. Davis, D. B. Marin, R. Kane, D. Patrick, E. R. Peskind, M. A. Raskind, and K. L. Puder, “The Caregiver Activity Survey (CAS): development and validation of a new measure for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease.,” Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry, vol. 12, no. 10, pp. 978–88, Oct. 1997. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9395929

FOCUS-GC Step-by-step Guide and Examples

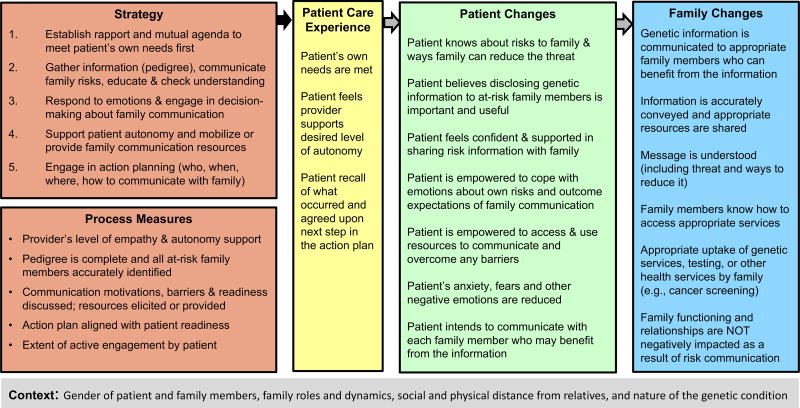

Two concrete examples of how FOCUS can be applied to genetic counseling were created. The first example, entitled “FOCUS on Genetic Counseling to Improve Family Risk Communication and Appropriate Uptake of Health Services”, is illustrated in Figure 2 and described briefly below. This example could be useful for researching the effectiveness of genetic counseling interventions on conditions, such as hereditary cancer syndromes and familial hypercholesterolemia, where genetic testing/screening can empower family members to access genetic services and take appropriate actions that can ultimately reduce morbidity and mortality (George, Kovak, & Cox, 2015).

Figure 2.

FOCUS on Genetic Counseling to Improve Family Communication and Appropriate Service Utilization

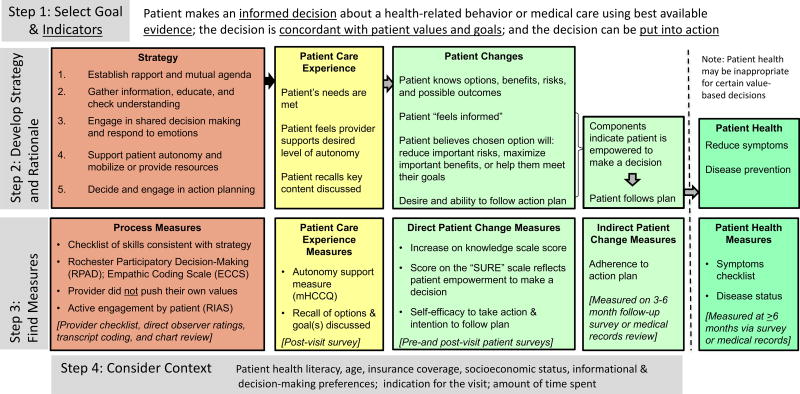

The second example uses the step-by-step guide to illustrate how FOCUS can be applied in designing research studies and is summarized in Figure 3. To complete the first step, we selected our primary goal and used Tables 3 and 4 to identify indicators or outcomes related to the goal. The primary goal was “to promote quality health decisions”; and the primary indicators/outcomes, selected to reflect the extent to which this goal is achieved, include: 1) patient makes an informed decision; 2) the decision is based upon best available evidence; 3) the decision aligns with the patient’s values and goals; and 4) the decision can be put into action.

Figure 3.

FOCUS on Genetic Counseling to Promote Quality Health Decisions

In the second step we created a strategy for the intervention by listing communication skills from Table 1a that together would likely help achieve the primary goal (either directly or indirectly). As part of this step we also began developing a rationale for choosing these specific skills based on logic, empirical research findings and other frameworks or theories in order to explain why and how combining these communication skills in a specific way would be expected to improve the select indicators and outcomes. The skills we combined to create our strategy included: 1) establish rapport and a mutual agenda; 2) gather information, educate, and check understanding; 3) respond to emotions and engage patient in decision making; 4) support patient autonomy and mobilize or provide resources; 5) decide and engage in action planning. These skills are each comprised of several processes, including several from the Ottowa Decision-making Framework and those that were identified as critical to shared decision making in a review article (Légaré et al., 2006; Makoul & Clayman, 2006). We then mapped out direct and indirect pathways through which our strategy may influence the patient care experience as well as cognitive, emotional or behavioral changes among the patient.

To complete step 3 we identified measures to ensure that the strategy was implemented with fidelity (process measures). Measures were also selected for inclusion on patient surveys in order to evaluate the patient care experience and measure direct patient changes (Figure 3). Additionally, indirect patient changes and patient health measures were considered for inclusion on a follow-up survey and medical record review 3–6 months later. Finally, to complete step 4 we considered some of the general contextual variables that might modify or confound decision making studies and are therefore important to measure so that they can be used as covariates in the analysis. Although we elected to create a somewhat general decision-making example, literature on a specific type of decision and/or specific setting in which it occurs may identify other important contextual variables.

DISCUSSION

The unique contribution of FOCUS is that it consolidates prior models, published literature, and professional experience into a more comprehensive framework that defines terms and helps postulate general mechanisms by which clinical communication services (including genetic counseling, health coaching and care-coordination) may influence patients and families either directly or indirectly and result in improved care experiences and health outcomes. FOCUS is purposefully agnostic to any specific outcome or context in order to maintain flexibility and applicability to a variety of clinical settings in which GC or other communication intense health services are provided. The examples we created demonstrate how FOCUS can be tailored to examine different outcomes. Ultimately, this type of framework may help in designing studies to demonstrate and establish the gold standard of quality in genetic counseling and other healthcare communication services more generally.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has defined quality based on the extent to which health care services are patient-centered, equitable, effective, timely, safe and efficient (Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). Development of quality measures begin with clinical research that links clinical care processes with the IOM quality indicators. The two examples we created using FOCUS can help conceptualize how GC may impact quality. Specifically, with regard to our first example, increasing family members’ uptake of testing may improve timeliness of identifying at-risk family members and contribute to effective care through the prevention or early detection of disease. In addition, efficiency can be improved through ordering single site testing for family members (as opposed to full gene sequencing); and this is only possible if a patient accurately communicates test results to family members. In relation to our second example, using a shared decision-making strategy is considered high quality care because it takes into consideration the patients’ needs, values, and goals and therefore the approach is patient-centered. Furthermore, a quality health decision is hypothesized to indirectly increase the effectiveness of care in some settings or contexts by improving patient adherence to evidence-based health recommendations.

Study Limitations

Despite the potential usefulness of FOCUS, there were limitations with the approach used to construct the framework. First, the process of developing the framework was not entirely systematic. However, it would have been impractical to review all literature within all relevant disciplines and to provide detailed examples or evidence for each of the proposed relationships between framework components. Thus, additional work is needed to comprehensively review research findings and to indicate the strength of evidence supporting or refuting the proposed relationships between constructs. Second, this framework was informed largely by the GC literature. As a result, some components of the framework may be less relevant to health service delivery that occurs outside the context of GC. Further, the process of consolidating and determining labels and definitions for FOCUS domains and constructs was challenging due to notable similarities between several outcomes or communication skills and processes as well as insufficient evidence to suggest that one label or description is superior to another. Subsequently, nuances in constructs and labels may have been lost during the consolidation process. Finally, there are several important limitations related to the sample measures included in the FOCUS tables. Although researchers may find some of these measures useful, we did not use any type of systematic method in their selection and we created several of the measures to serve as examples. Consequently, we are unable to endorse any of the measures because we have not evaluated or generated evidence of their reliability or validity.

Practice Implications

FOCUS could be used to evaluate GC service delivery and help answer relevant clinical questions like: 1) How do genetic counselors contribute to improvements in patient care experiences and outcomes? and 2) What are best practices in genetic counseling? Professional consensus regarding terminology related to GC processes and outcomes together with widespread use of a consolidated framework (such as a modified version of FOCUS) may help move genetic counseling outcomes research ahead more quickly in order to build a strong evidence base for GC practice. Currently evidence supporting linkages between communication strategies and outcomes is somewhat limited in GC (Bettina Meiser et al., 2008; Paul, Metcalfe, Stirling, Wilson, & Hodgson, 2015). However, several propositions linking some of the FOCUS constructs do exist and provide rich areas of continued exploration. For example, patient-centered strategies based on Self-determination Theory, Motivational Interviewing techniques, and/or the Extended Parallel Process Model have increased autonomous motivation, improved perceived competence and self-efficacy, and/or changed cognitions, emotions or behaviors (DiClemente et al., 2009; Kinney et al., 2014; Lundahl et al., 2013; Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Pengchit et al., 2011; Ruiter, Kessels, Peters, & Kok, 2014). These strategies consist of skills and techniques that are included in FOCUS such as asking the patient what she/he wants to achieve; refraining from judgment; encouraging questions; exploring and resolving ambivalence in decision making; altering risk perceptions; and/or promoting beliefs that certain actions or resources can help the patient effectively mitigate their risks.

Research Recommendations

In order for FOCUS to impact clinical practice, additional efforts are needed that go beyond the scope of the current study. Identifying appropriate outcome measures is still an important research area that will require additional efforts. A few articles have identified and reviewed measures that capture some GC outcomes (M McAllister & Dearing, 2015; B Meiser et al., 2001; Payne, Nicholls, McAllister, Macleod, et al., 2007) and we have included several other potential measures as examples. However, it will be critical to ensure these measures are well validated in a variety of GC contexts. Efforts will also be needed to further hypothesize and test specific direct and indirect relationships between constructs using methods such as structural equation modeling. As empirical evidence is gathered to support or refute hypothesized relationships, additional modifications to FOCUS may be necessary. We also anticipate that constructs will be added to the framework over time and that FOCUS will be used in conjunction with other models and theories.

Conclusion

FOCUS provides a comprehensive way of thinking about clinical communication services and has the potential to help researchers: 1) develop ideas about how to evaluate clinical communication services (including genetic counseling); 2) organize, categorize, and define a broad array of possible outcomes; 3) select outcomes and measures; 4) hypothesize how communication strategies may positively impact health care quality; 5) guide comparative effectiveness research to determine whether and how differences in GC may or may not be associated with differences in patient outcomes. Use and refinement of this type of macro-level framework is expected to improve our ability to conceptualize and summarize genetic counseling outcome studies (both past and future) and help to collate much needed evidence on what communication strategies could be endorsed as best practices in GC. It is our hope that patients, healthcare providers, and researchers in many different areas may benefit from applying this type of framework in research and practice.

Acknowledgments

Partial support for Deborah Cragun’s time was provided during her postdoctoral training fellowship funded by a NCI R25 training grant awarded to Moffitt Cancer Center (5R25CA147832-05). However, this work reflects the authors' opinions and has neither been reviewed nor endorsed by the NCI or entities acknowledged below. The authors would like to acknowledge the National Society of Genetic Counselors outcomes work group because serving on this group revealed the need for and helped in conceptualizing this framework. Deborah Cragun would also like to acknowledge that framework development was inspired and/or influenced by: 1) training she received from her mentors (Dr. Rita DeBate and Dr. Tuya Pal); 2) discussions with Dr. Courtney Scherr and Dr. Anita Kinney; and 3) participation in the Mentored Training in Dissemination and Implementation Research in Cancer (MT-DIRC) program. MT-DIRC is supported through a NCI grant (R25CA171994-02) and by the Veterans Administration.

Dr. Christina Palmer served as Action Editor on the manuscript review process and publication decision.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Heather Zierhut, PhD, MS and Deborah Cragun, PhD, MS declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Subjects & Infomed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Animal Studies No animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article

References

- Accreditation Counsel for Genetic Counseling. Practice-Based Competencies for Genetic Counselors Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt BA, Biesecker BB, Mastromarino CL. Goals, benefits, and outcomes of genetic counseling: client and genetic counselor assessment. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000;94(3):189–97. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20000918)94:3<189::aid-ajmg3>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chivers Seymour K, Addington-Hall J, Lucassen AM, Foster CL. What facilitates or impedes family communication following genetic testing for cancer risk? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of primary qualitative research. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2010;19(4):330–42. doi: 10.1007/s10897-010-9296-y. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-010-9296-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press. 2001 Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25057539. [PubMed]

- DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler M. In: Emerging theories in health promotion pracitce and research. 2. DiClemente RJ, Crosby RA, Kegler M, editors. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Donabedian A. The Quality of Care - How Can It Be Assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George R, Kovak K, Cox SL. Aligning policy to promote cascade genetic screening for prevention and early diagnosis of heritable diseases. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2015;24(3):388–99. doi: 10.1007/s10897-014-9805-5. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-014-9805-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health. 2010;31:399–418. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha Dinh TT, Bonner A, Clark R, Ramsbotham J, Hines S. The effectiveness of the teach-back method on adherence and self-management in health education for people with chronic disease: a systematic review. JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2016;14(1):210–47. doi: 10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2296. http://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2016-2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallowell N, Lawton J, Gregory S. Reflections on Research: The Realitities of Doing Research in the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Open University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann JE, Veach PM, MacFarlane IM, LeRoy BS. Genetic counselor perceptions of genetic counseling session goals: a validation study of the reciprocal-engagement model. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2015;24(2):225–37. doi: 10.1007/s10897-013-9647-6. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-013-9647-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Epstein RM, Winters PC, Fiscella K, Duberstein PR, Gramling R, Kravitz RL. Values and options in cancer care (VOICE): study design and rationale for a patient-centered communication and decision-making intervention for physicians, patients with advanced cancer, and their caregivers. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:188. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-188. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-13-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House JS. Work stress and social support. Addison-Wesley Pub Co; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon CC, Palakshappa D, Feudtner C. Logic Models--Tools to Bridge the Theory-Research-Practice Divide. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(9):801–2. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1365. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney AY, Boonyasiriwat W, Walters ST, Pappas LM, Stroup AM, Schwartz MD, Higginbotham JC. Telehealth personalized cancer risk communication to motivate colonoscopy in relatives of patients with colorectal cancer: the family CARE Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology : Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(7):654–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.6765. http://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.51.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Légaré F, O’Connor AC, Graham I, Saucier D, Côté L, Cauchon M, Paré L. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Canadian Family Physician Medecin de Famille Canadien. 2006;52:476–7. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17327891. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JS, Li Y, Valdesolo P, Kassam KS. Emotion and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015;6633 doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling. 2013;93(2):157–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Education and Counseling. 2006;60(3):301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Dearing A. Patient reported outcomes and patient empowerment in clinical genetics services. Clinical Genetics. 2015;88(2):114–21. doi: 10.1111/cge.12520. http://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Moldovan R, Paneque M, Skirton H. The need to develop an evidence base for genetic counselling in Europe. European Journal of Human Genetics : EJHG. 2016;24(4):504–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.134. http://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Payne K, Macleod R, Nicholls S, Donnai Dian, Davies L. Patient empowerment in clinical genetics services. Journal of Health Psychology. 2008;13(7):895–905. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095063. http://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308095063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister M, Payne K, Nicholls S, MacLeod R, Donnai D, Davies LM. Improving service evaluation in clinical genetics: identifying effects of genetic diseases on individuals and families. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16(1):71–83. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9046-3. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-006-9046-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcallister M, Wood A, Dunn G, Shiloh S, Todd C. The Genetic Counseling Outcome Scale: A new patient-reported outcome measure for clinical genetics services. Clinical Genetics. 2011;79:413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01636.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Butow PN, Barratt AL, Schnieden V, Gattas M, Kirk J Psychological Impact Collaborative Group. Long-term outcomes of genetic counseling in women at increased risk of developing hereditary breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling. 2001;44(3):215–25. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser B, Irle J, Lobb E, Barlow-Stewart K. Assessment of the content and process of genetic counseling: a critical review of empirical studies. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2008;17(5):434–51. doi: 10.1007/s10897-008-9173-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-008-9173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: helping people change. 3. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Measures Clearninghouse. 2017 doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. Retrieved February 6, 2017, from https://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nci, DCCPS, & Arp. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing & Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: NIH publication; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsen P, Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Walker A, Johnston M, Pitts N, Baumgardner M. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implementation Science. 2015;10(1):53. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. http://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]