Abstract

This study examined teacher–child conflict as a possible mediator of the effects of temperamental anger and effortful control on subsequent externalizing behavior. Reciprocal influences between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior were also examined. Participants were 1,152 children (49% female; 81.6% non-Hispanic white) from the SECCYD. Multivariate growth curve modeling revealed that greater effortful control at age 54 months indirectly predicted lower levels of, and subsequent changes in, externalizing behavior from kindergarten to grade 6 through reduced teacher–child conflict. An alternative model, in which greater effortful control predicted lower teacher–child conflict through lower externalizing behavior, received less support. Within persons, greater than expected teacher–child conflict predicted greater than expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior concurrently and over time.

A growing literature supports an association between adverse child temperament and the development of externalizing behavior (Olson, Sameroff, Kerr, Lopez, & Wellman, 2005; Zhou Lengua, & Wang, 2009). Although it is defined in various ways, adverse temperament is often characterized by poor attention regulation, low adaptability to environmental changes, high activity level, and proneness to intense negative affect (i.e., “difficult temperament”, Thomas & Chess, 1977); it can also involve non–compliance and resistance to adult control (Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994). Adverse temperament typically includes high levels of negative affect (especially anger/frustration, hereafter referred to as “anger”) and low levels of attentional and inhibitory control (i.e., poor effortful control). In this study, adverse temperament is operationalized as high anger and poor effortful control. Externalizing behavior encompasses a broad array of behaviors that are disruptive, disobedient, aggressive, or antisocial with key features being aggression and delinquent behavior (Achenbach, 1991). Although adverse temperament is positively associated with subsequent externalizing behavior, the mechanisms underlying this association are not well understood. Given that childhood externalizing behavior is associated with myriad negative outcomes in adolescence and adulthood, including poor peer relationships, academic problems, and antisocial behavior (Hinshaw & Melnick, 1995; Lucio, Hunt, & Bornovalova, 2012), the processes linking adverse temperament to externalizing behavior merit continued study.

In an extensive review of the literature, Rothbart and Bates (2006) identified several potential models of temperament effects on externalizing behavior. One possibility is that adverse temperament represents a proclivity for disruptive, impulsive behavior that reflects either a predisposition towards, or an early expression of, externalizing behavior (i.e., a direct effect). A second possibility is that adverse temperament shapes children’s experiences in key social contexts in ways that affect their subsequent development (i.e., an indirect effect). More precisely, adverse temperament traits such as negative affect and poor effortful control may influence the ways that social partners respond to a child (Shiner & Caspi, 2003), resulting in negative social interactions that in turn contribute to externalizing behavior. To date, most empirical work on such indirect effects has focused on parent–child relationships and has supported an association between adverse child temperament (or its components) and less positive parent–child relationships (Rothbart & Bates, 2006). However, adverse temperament could also influence other critical social relationships, including those with teachers. In this study, we explored the role of teacher–child conflict as an intervening factor linking adverse temperament to externalizing behavior.

Teacher–child relationships play a fundamental role in children’s learning and behavioral adjustment (Baker, 2006; Hamre & Pianta, 2001), and poor quality relationships involving high levels of conflict are associated with higher levels of child academic and behavioral problems, including externalizing behavior (Doumen et al., 2008; Silver, Measelle, Armstrong, & Essex, 2010). Furthermore, a small body of work has shown that teacher–child conflict is positively associated with temperamental anger and negatively associated with effortful control in preschool and first grade (e.g., Justice, Cottone, Rimm-Kaufman, & Mashburn, 2008; Rudasill & Rimm-Kaufman, 2009). Given these findings, it is plausible that adverse temperament influences externalizing behavior indirectly by increasing the amount of teacher–child conflict. It is also possible that child externalizing behavior contributes to increased teacher–child conflict. Indeed, negative interactions with teachers could contribute to further externalizing behavior and vice versa, such that conflict and externalizing become mutually reinforcing (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). To elucidate these processes, we examined the predictive relations between two adverse temperament traits—high anger and poor effortful control—and subsequent teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior. We also examined bidirectional associations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior across the elementary school years.

Temperament and Externalizing Behaviors

Typically, temperament traits that are indicative of more intense reactions to the environment (e.g., quick to anger) or difficulty with regulating behaviors and emotions (e.g., poor effortful control) present greater challenges for parents, peers, and teachers; moreover, these traits have shown relatively consistent associations with externalizing behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001; Gartstein, Putnam, & Rothbart, 2012). In general, negative affectivity, especially anger, is associated with greater externalizing behavior, whereas effortful control (including attention regulation and inhibitory control) is associated with less externalizing behavior. Among Dutch preschool children, greater externalizing behavior was associated with higher negative affect and lower effortful control (DePauw, Mervielde, & Van Leeuwen, 2009). Similarly, greater externalizing behavior was associated with higher anger and lower effortful control among U.S. three–year–olds, although the associations varied by reporter (Olson et al., 2005). For children in grades 3–5, Lengua and Kovacs (2005) reported a positive link between externalizing behavior and temperamental irritability (similar to anger) but no association between self–regulation and externalizing behavior. Lastly, among Dutch preadolescents, a profile of externalizing problems (without comorbidity) was associated with higher frustration and lower effortful control (Oldehinkel, Hartman, DeWinter, Veenstra, & Ormel, 2004). It is also noteworthy that effects of preschool temperament can be enduring: higher negative affect (including anger) and lower effortful control at age 4 predicted greater externalizing behavior in adolescence (Honomichl & Donnellan, 2012).

Temperament and Teacher–Child Conflict

Temperament characteristics can set the stage for warm, comfortable relationships or for conflict and stress with teachers. High levels of child anger may increase the burden for teachers who must deal with students’ outbursts. Similarly, children with poor effortful control require more hands-on involvement by teachers to enforce limits and help them regulate their behavior. Low effortful control is also characterized by poor attention, so teachers may need to work harder to keep children engaged and on task. In this way, children’s temperament shapes their interactions with teachers, who in turn create the social milieu of the early elementary classroom (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000).

Although teachers have received relatively little attention in the temperament literature, several studies have linked child anger and effortful control to teacher–child conflict. In one study, teachers reported more conflict with preschool children who were higher in anger (Justice et al., 2008). In another study, higher child anger was associated with a less positive teacher–child relationship in kindergarten, whereas higher effortful control predicted a more positive teacher–child relationship (Valiente, Swanson, & Lemery-Chalfant, 2012). Among first graders, Rudasill and Rimm-Kaufman (2009) found a negative association between effortful control and teacher–child conflict that was mediated by teacher-initiated interactions. Children with lower effortful control received more interactions initiated by teachers, and these interactions, in turn, predicted more conflict.

Teacher–Child Relationships and Externalizing Behavior

School is a key social context outside the family with significant implications for children’s academic and social adjustment. There is abundant evidence that positive teacher–child relationships are beneficial for children’s academic, social, and behavioral outcomes, whereas negative teacher–child relationships are associated with poor academic performance and higher externalizing and antisocial behaviors (e.g., Baker, 2006; Hamre & Pianta, 2001). For example, Meehan, Hughes, and Cavell (2003) found that supportive teacher–student relationships were associated with reduced levels of aggressive behavior over a two–year period among aggressive second and third graders, especially African American and Hispanic children. Silver and colleagues (2010) identified three groups of children over the elementary years based on teacher–rated externalizing behavior scores in grades K, 1, 3, and 5. Higher teacher–child conflict in kindergarten was associated with membership in the chronic high externalizing group and the low increasing externalizing group compared to the low externalizing group.

The transition to school is a critical time for the development of teacher–child relationships and school adjustment. Because the transition entails a new social setting and places significant demands on children to pay attention and follow instructions, it is often challenging for children, particularly those with poor regulatory capacity or a predisposition towards negative affect (Goldsmith, Aksan, Essex, Smider, & Vandell, 2001). From an ecological perspective, children’s positive adjustment to school depends on characteristics of the child (e.g., temperament), as well as characteristics of the environment (e.g., teacher–child relationships), and interactions between the child and environment over time (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). Empirical findings indicate that children who have positive experiences with the transition to school tend to have continued positive experiences and successful adjustment in the school setting; conversely, those who have negative experiences, such as poor teacher–child relationships, tend to have problems with later teacher–child relationships, peer relationships, and academic performance (O’Connor, 2010; Rudasill, Neihaus, Buhs, & White, 2013).

Notably, conflict with teachers during the transition to school is associated with the development of children’s externalizing problems. Pianta and Stuhlman (2004) found that higher levels of teacher–child conflict in kindergarten and first grade predicted higher levels of first grade externalizing behavior with prior externalizing controlled. Furthermore, among boys, greater conflict with teachers in kindergarten predicted more disciplinary infractions in seventh and eighth grades (Hamre & Pianta, 2001). Similarly, O’Connor, Dearing, and Collins (2011) reported that children who had closer and less conflictual relationships with teachers at the start of elementary school had lower levels of externalizing behavior into fifth grade. The findings suggest that high levels of teacher–child conflict may contribute to externalizing behavior.

Externalizing Behavior and Teacher–Child Conflict

Although teacher–child conflict predicts externalizing behavior, there is also evidence that externalizing behavior contributes to more conflictual teacher–child relationships (O’Connor, 2010). Ladd, Birch, and Buhs (1999) found that observer-rated antisocial behavior during the first 10 weeks of kindergarten was negatively associated with the quality of teacher–child relationships in the following weeks (e.g., less warmth and nurturance; more conflict and anger). Similarly, Ladd and Burgess (1999) reported that aggressive children, identified from teacher-rated behaviors in the fall of kindergarten, had higher levels of teacher–child conflict through second grade compared to a normative group of children. Among children in grades 3 to 5, greater externalizing behavior concurrently predicted higher teacher–child conflict (Murray & Murray, 2004). Thus, a possible alternative model is that temperament traits influence externalizing behavior which then influences teacher–child conflict.

Reciprocal Effects Between Teacher–Child Conflict and Externalizing Behavior

Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta’s (2000) theory suggests a transactional process where children’s negative interactions and externalizing behavior are mutually reinforcing and each contributes to the maintenance and progression of the other. Such transactional processes are in keeping with contemporary models of child development in which interactions between children and their social environment continually shape both children’s behavior and aspects of their social-relational context (e.g., Sameroff, 2009). However, tests of reciprocal effects between teacher–child relationships and student behavior are rare. A few studies have found support for both sets of predictive relations, but in separate analyses. Howes and colleagues (2000) showed that greater preschool behavior problems predicted higher teacher–child conflict in kindergarten and also that higher teacher–child conflict in preschool predicted more kindergarten behavior problems. Birch and Ladd (1998) reported that children’s antisocial behavior, rated by their kindergarten teachers, predicted higher conflict and less closeness in relationships with teachers in first grade; conversely, teacher–child conflict in kindergarten accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in children’s first grade aggression towards peers. Rudasill (2011) found that children with poor effortful control had more conflict with teachers in first grade and elicited more teacher-initiated interactions. In turn, more teacher-initiated interactions in first grade predicted more teacher-initiated interactions in third grade, which predicted more teacher–child conflict. Although not a test of reciprocal effects, this study suggests that different teachers find it necessary to intervene with the same children and tend to report higher levels of conflict with them, pointing to patterns of student–teacher interaction that carry over into future grades.

To our knowledge only one study has directly examined reciprocal effects between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior. Doumen and colleagues (2008) found that Dutch school children who were more aggressive at the start of kindergarten showed increased teacher–child conflict at mid-year, controlling on initial levels; in turn, children with higher levels of teacher–child conflict at mid-year showed further increases in aggression by the end of the school year. Although limited to a single grade, the findings suggest a short-term reciprocal effect. Moreover, other studies discussed in this section span multiple years and show that child behavior and teacher–child conflict predict each other longitudinally into the next grade, providing preliminary support for reciprocal effects that transcend a single school year.

Reporter Effects on the Relations Between Teacher–Child Conflict and Externalizing

Studies of associations between teacher–child conflict and child externalizing behavior often use teacher reports to measure both constructs (e.g., Doumen et al., 2008; Ladd & Burgess 1999; Silver et al. 2010). The rationale is that the teacher is in the best position to rate her relationship with the child and to report on the child’s level of externalizing behavior within the classroom setting. However, relying solely on teachers could inflate the association between teacher-rated conflict and teacher-rated externalizing behavior owing to shared source variance. Therefore, it is useful to include additional reporters, recognizing that other reporters (e.g., parents) observe children in multiple settings and may hold different views of the child than teachers do. Indeed, when both mother- and teacher-reports are used, results may differ (e.g., Olson et al., 2005). Nonetheless, it is likely that children’s behavior shows some stability across contexts, and including multiple reporters allows an examination of reporter effects.

To summarize, there is evidence that adverse temperament influences the quality of teacher–child relationships and that teacher–child conflict contributes to levels of and increases in externalizing behavior; there is also evidence that children’s externalizing behavior predicts teacher–child conflict. Two issues require further attention. First, although some studies have documented an association between child temperament traits and teacher–child relationships (Justice et al., 2008; Rudasill & Rimm-Kaufman, 2009) or between poor teacher–child relationships and externalizing problems (e.g., Silver et al., 2010), the mediating role of teacher–child relationships in the temperament–externalizing behavior association has not been examined. Second, most studies have tested only unidirectional models of the predictive relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior, perhaps because very few studies include the repeated assessments needed to test dynamic, transactional processes. Although Doumen et al. (2008) provided evidence of reciprocal effects during kindergarten, we know of no studies that have examined these reciprocal effects over longer periods of time or with older children, particularly while considering the role of temperament. The present study was intended to address these gaps in the literature.

Present Study

In this study, we joined evidence regarding the role of early temperament in shaping teacher–child relationships with Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta’s (2000) notion that negative teacher–child interactions and child externalizing behavior mutually reinforce each other. Specifically, we hypothesized that higher anger and lower effortful control prior to kindergarten would predict higher levels of and greater increases in teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior during elementary school. We further hypothesized that there would be indirect relations between temperament traits and externalizing behavior through teacher–child conflict, and potentially between temperament traits and teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior. To explore possible reciprocal effects between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior, we examined the lagged within-person relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior in two alternative models: in one model, greater teacher–child conflict predicted greater externalizing behavior; in the other, greater externalizing behavior predicted greater teacher–child conflict. We expected that teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior would mutually influence each other, as indicated by significant lagged relations between these variables over time. Evidence of within-person reciprocal effects would be strongest if teacher–child conflict at one occasion predicted increased externalizing behavior at the next occasion with prior externalizing behavior controlled, and vice versa. To examine possible reporter differences, models included both teacher-reported and mother-reported externalizing behavior. Finally, because there are gender differences in levels of effortful control (Else-Quest, Hyde, Goldsmith, & Van Hulle, 2006), teacher–child conflict (e.g., Ewing & Taylor, 2009), and externalizing behavior (Card, Stucky, Sawalani, & Little, 2008), as well as associations between socioeconomic status (SES) and externalizing behavior (Letourneau, Duffett-Leger, Levac, Watson, & Young-Morris, 2013), we controlled for gender and income-to-needs effects in the analyses.

Method

Participants

Data came from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD), which followed a socioeconomically diverse cohort of children from birth to age 15 years. In 1991, new mothers were recruited from hospitals in ten locations across the U.S. (e.g., Little Rock, AR; Irvine, CA; Lawrence, KS; Boston, MA). Mothers were eligible if they were healthy, at least 18 years of age, had a single birth that resulted in a healthy baby, reported no substance abuse, and were not planning to move. Of 8,986 mothers, 5,416 (60%) were eligible and agreed to be contacted, and a randomly selected subset was enrolled (N = 1,364 children).

Data for this study were drawn from Phase II of the SECCYD (1996–1999), which followed the children from age 54 months to grade 1, and Phase III (2000–2004), which followed them from grades 2 to 6. To be included in the analysis, children had to have at least one value for one time–varying outcome variable (i.e., teacher–child conflict or externalizing behavior); children who did not meet this criterion were excluded (n = 212). All other children in the SECCYD sample were retained in the analysis. The analytic sample included 1,152 children (49% female; 81.6% white, non-Hispanic; 11.7% African American; 6.7% other racial/ethnic groups). At the 54-month assessment, children were 4.64 years of age on average (SD = 0.09), and most mothers (71.8%) had at least some college education. Attrition analyses comparing the analytic sample (n = 1,152) to the attrited sample (n = 212) indicated that children from lower income families, F(1, 1,271) = 30.93, p <.01, η2 = .02, were slightly less likely to be retained in the analytic sample than children from higher income families. Additionally, non-White children were less likely to stay in the study than White children, χ2(1) = 6.47, p <.05, and mothers who had less than a college degree were less likely to be retained than mothers with at least a bachelor’s degree, χ2(1) = 28.11, p < .001. Teachers of the child participants were primarily female (97.18%) and Caucasian (87.7%), with a mean of 15.54 years of teaching experience (SD = 9.06). In most cases there was only one study child per classroom.

Measures

Primary study measures (described below) included mother reports of child anger and effortful control at age 54 months, annual teacher reports of teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior in kindergarten through grade 6, and mother reports of externalizing behavior in kindergarten, grade 1, and grades 3–6. Controls included gender and family income-to-needs (a proxy for socioeconomic status). Further details on the SECCYD measures can be found at: http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/seccyd/Pages/overview.aspx#initiating.

Measurement models

Before testing the multivariate growth curves, measurement models were conducted for the time-invariant predictors (anger and effortful control) and time-varying outcomes (teacher–child conflict and teacher- and mother-reported externalizing behavior). Items on these measures were treated as ordinal indicators (i.e., using item response theory; IRT). Following best practice in IRT, reliability was assessed at each standard deviation above and below the mean of the latent variable for that measure (see Measures). For the time-varying outcomes, we specified full scalar invariance across the 6–7 occasions to ensure comparable measurement across grades. Given the complexity of the multivariate growth models, factor scores were extracted from the measurement models and used as observed variables to represent each construct.

Temperament at 54 months

Two temperament traits—anger and effortful control—were measured using the Children’s Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ; Rothbart, Ahadi, & Hershey, 1994). Mothers were asked to rate how well each item described their child in the past 6 months using a 7-point scale, in which 1 = extremely untrue and 7 = extremely true.

Anger was indicated with 10 items measuring children’s displays of negative affect in response to having to stop an activity or being prevented from doing something (e.g., “Gets angry when called in from play”). Reliability > .80 was observed from approximately −4.0 to +2.5 SDs of the anger factor, indicating excellent reliability across the range of scores.

Effortful control was assessed with 8 items measuring attentional focusing (e.g., “When building or putting something together, [child] becomes very involved in what s/he is doing, and works for long periods”), and by 10 items measuring inhibitory control (e.g., “Can easily stop an activity when s/he is told ‘no’”). Reliability > .80 was observed from approximately −5.0 to +3.0 SDs of the effortful control factor, indicating excellent reliability.

Teacher–child conflict

In kindergarten and grades 1–6, teachers completed the 7-item Teacher–Child Conflict subscale from a shortened, 15-item version of the Student Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS; Pianta, 2001). Teachers were asked to determine how well each item described the student–teacher relationship on a 5-point scale in which 1 = definitely does not apply and 5 = definitely applies. Sample items are: “This child and I always seem to be struggling with each other” and “Dealing with this child drains my energy.” Reliability > .80 was observed from approximately −0.5 to +2.4 SDs of the teacher–child conflict latent factor. The STRS has been widely used to measure teacher–child conflict. It assesses the nature of the relationship between the teacher and the child.

Externalizing behavior

In kindergarten and grades 1–6, teachers completed the Teacher Report Form (TRF), the teacher version of the Child Behavior Check List (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). Mothers completed the CBCL in kindergarten, grade 1, and grades 3–6. The CBCL and TRF are widely used with children and adolescents and have shown high internal consistency and predictive validity (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). For both teachers and mothers, externalizing behavior was measured with items from the Delinquent Behavior and Aggressive Behavior scales. One delinquency item on use of alcohol/drugs for non-medical purposes was dropped for each reporter owing to low endorsement (< 1%). Thus, for teachers, there were 33 TRF items (8 items for delinquent behavior and 25 items for aggressive behavior) and for mothers there were 32 CBCL items (12 items for delinquent behavior and 20 items for aggressive behavior). Examples of delinquent behaviors include “Doesn’t seem to feel guilty after misbehaving” and “Lying or cheating.” Examples of aggressive behaviors include “Disobedient at school” and “Gets in many fights.” Most items on the TRF and CBCL are identical and do not refer to a specific setting; however, 14 items differ to some degree. Teachers and mothers were asked how well each item described the target child on a 3–point scale in which 0 = not true and 2 = very true. To facilitate estimation, if a value of “2” was chosen for < 1% of all responses for an item across grades, the value “2” was recoded as “1” for that item; this occurred for 7 items on the TRF and 13 items on the CBCL. Reliability > .80 was observed from approximately −0.4 to +3.8 SDs of the externalizing behavior factor based on the teacher reports, and from approximately −1.3 to +4.6 SDs based on the mother reports.

It is important to note that items on the Teacher–Child Conflict scale assess the nature of the relationship between the teacher and the child, and do not ask teachers about specific behaviors the child displays. In contrast, the measure of externalizing behaviors asks teachers to report on the frequency of specific behaviors, but does not attempt to assess how these behaviors affect the teacher-child relationship.

Sociodemographic variables

Control variables were child gender (0 = girls and 1 = boys) as reported by mothers at 1 month of age and the income–to–needs ratio (defined as the total household income at 1 month of age divided by the index for the poverty line). Because the distribution of income-to-needs ratio was positively skewed, this variable was log-transformed.

Analytic Method

To address the research questions we conducted a series of multivariate latent growth curve models using Mplus v. 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). Absolute model fit was assessed using the Comparative Fix Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). CFI values ≥ .95 and RMSEA values ≤ .05 indicate good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Owing to the large number of statistical tests, alpha was set at .01. Missing data were addressed using full-information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML).

Grade was treated as the time variable, ignoring trivial differences in assessment date. Change across grades in each outcome variable (teacher–child conflict, teacher-reported externalizing behavior, and mother-reported externalizing behavior) was modeled using a latent basis (see Bollen & Curran, 2006). In these models, a latent intercept factor was specified by fixing all factor loadings to 1. A latent slope factor was specified by fixing the kindergarten factor loading to 0, the grade 6 factor loading to 1, and freely estimating the other factor loadings. This approach allows the pattern of change to be captured by a single factor instead of separate factors for linear and nonlinear change, respectively. The intercept factor is interpreted as the predicted value at kindergarten, and the slope factor as the overall pattern of change across all grades. The slope factor mean captures the average growth trajectory, whereas the slope factor variance captures individual differences in trajectories.

We first estimated an unconditional growth model (i.e., without predictors) to describe the average growth trajectory and individual differences in growth trajectories in the three outcome variables. We then estimated conditional multivariate growth models to see how well the time-invariant predictors (anger and effortful control at 54 months, gender, and income-to-needs ratio at 1 month) predicted the intercept and slope factors for teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior. To reduce the number of analyses, we specified the models following Hoffman (2015). This allowed us to estimate the effects of the time-invariant predictors on teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior (i.e., between-person effects), as well the within-person relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior, in a single model. The within-person effects were estimated using the residuals for teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior (i.e., values at each grade after controlling for individual differences in growth; see also Curran, Howard, Bainter, Lane, & McGinley, 2014). This allowed us to estimate the extent to which a child’s score at any given time point is higher or lower than predicted by her individual intercept and slope factors. All models included separate measures of mother-reported and teacher-reported externalizing behavior.

We tested the hypothesized Model A, in which temperament predicted externalizing behavior through teacher–child conflict. We also tested an alternative model (Model B), in which temperament predicted teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior. Having two models was necessary to test for reciprocal effects between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior while taking their concurrent predictive relationship (i.e., the concurrent regression coefficient) into account. For both models we tested the significance of the indirect effects with bias–corrected bootstrap standard errors (MacKinnon, Lockwood & Williams, 2004) estimated via MODEL INDIRECT in Mplus.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. Higher levels of temperamental anger at 54 months were associated with more teacher–child conflict, teacher-reported externalizing behavior, and mother-reported externalizing behavior in all grades, whereas higher levels of effortful control were associated with lower levels of all three outcomes. Anger and effortful control were negatively correlated. The three outcomes were positively correlated, with stronger correlations observed between teacher–child conflict and teacher-reported externalizing behavior than between teacher–child conflict and mother-reported externalizing behavior. To examine the proportion of between-person and within-person variability in the three outcome variables, we estimated intraclass correlations: they were .60 for teacher–child conflict, .71 for teacher-reported externalizing behavior, and .71 for mother-reported externalizing behavior. Thus, although most of the variability in the outcomes was due to between–person differences, some of the variability was due to within-person differences.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, sample size, and correlations for study variables

| Variable | M | SD | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Anger at 54 months | 0.00 | 0.90 | 1047 | ||||||||||

| 2. Effortful Control at 54 months | 0.01 | 0.94 | 1047 | −.36 | |||||||||

| 3. Girl vs. Boy at 1 month | 0.51 | 0.50 | 1152 | .07 | −.17 | ||||||||

| 4. Income-to-Needs Ratio at 1 month | 0.72 | 0.96 | 1079 | −.06 | .25 | −.01 | |||||||

| 5. Teacher-Child Conflict Kindergarten | −0.20 | 0.72 | 1007 | .14 | −.23 | .18 | −.11 | ||||||

| 6. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 1 | 0.01 | 0.53 | 1007 | .16 | −.31 | .22 | −.18 | .61 | |||||

| 7. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 2 | −0.02 | 0.56 | 936 | .15 | −.30 | .22 | −.15 | .63 | .70 | ||||

| 8. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 3 | 0.05 | 0.59 | 978 | .16 | −.31 | .24 | −.19 | .59 | .70 | .74 | |||

| 9. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 4 | 0.01 | 0.57 | 917 | .16 | −.28 | .23 | −.21 | .57 | .60 | .66 | .72 | ||

| 10. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 5 | 0.07 | 0.56 | 930 | .15 | −.28 | .21 | −.23 | .46 | .66 | .62 | .65 | .68 | |

| 11. Teacher-Child Conflict Grade 6 | −0.01 | 0.58 | 857 | .12 | −.29 | .24 | −.22 | .39 | .60 | .48 | .58 | .64 | .68 |

| 12. Teacher-Report EB Kindergarten | −0.02 | 0.86 | 1007 | .16 | −.28 | .26 | −.13 | .74 | .59 | .61 | .58 | .55 | .46 |

| 13.Teacher-Report EB Grade 1 | 0.12 | 0.79 | 1008 | .15 | −.33 | .27 | −.18 | .55 | .79 | .67 | .66 | .59 | .58 |

| 14. Teacher-Report EB Grade 2 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 923 | .17 | −.35 | .27 | −.18 | .58 | .69 | .80 | .71 | .64 | .62 |

| 15. Teacher-Report EB Grade 3 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 983 | .16 | −.32 | .25 | −.22 | .54 | .66 | .70 | .81 | .68 | .62 |

| 16. Teacher-Report EB Grade 4 | 0.08 | 0.84 | 915 | .19 | −.33 | .29 | −.22 | .53 | .65 | .67 | .71 | .79 | .66 |

| 17. Teacher-Report EB Grade 5 | 0.13 | 0.83 | 930 | .16 | −.27 | .29 | −.22 | .48 | .62 | .63 | .63 | .67 | .80 |

| 18. Teacher-Report EB Grade 6 | 0.01 | 0.86 | 858 | .11 | −.27 | .32 | −.19 | .42 | .59 | .51 | .60 | .61 | .63 |

| 19. Mother-Report EB Kindergarten | 0.26 | 0.89 | 1046 | .46 | −.43 | .08 | −.15 | .29 | .30 | .33 | .29 | .28 | .25 |

| 20. Mother-Report EB Grade 1 | 0.13 | 0.90 | 1009 | .47 | −.41 | .07 | −.17 | .32 | .37 | .38 | .36 | .35 | .31 |

| 21. Mother-Report EB Grade 3 | 0.02 | 0.91 | 1007 | .39 | −.38 | .07 | −.19 | .28 | .37 | .39 | .37 | .38 | .33 |

| 22. Mother-Report EB Grade 4 | −0.06 | 0.91 | 992 | .39 | −.38 | .06 | −.18 | .26 | .32 | .34 | .33 | .35 | .33 |

| 23. Mother-Report EB Grade 5 | −0.16 | 0.94 | 995 | .37 | −.35 | .07 | −.15 | .26 | .33 | .34 | .34 | .34 | .32 |

| 24. Mother-Report EB Grade 6 | −0.20 | 0.95 | 987 | .38 | −.37 | .07 | −.18 | .24 | .34 | .34 | .35 | .35 | .34 |

| Variable | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12. Teacher-Report EB Kindergarten | .41 | ||||||||||||

| 13. Teacher-Report EB Grade 1 | .55 | .70 | |||||||||||

| 14. Teacher-Report EB Grade 2 | .53 | .73 | .82 | ||||||||||

| 15. Teacher-Report EB Grade 3 | .60 | .67 | .76 | .83 | |||||||||

| 16. Teacher-Report EB Grade 4 | .61 | .68 | .74 | .81 | .85 | ||||||||

| 17. Teacher-Report EB Grade 5 | .62 | .56 | .68 | .76 | .72 | .81 | |||||||

| 18. Teacher-Report EB Grade 6 | .77 | .51 | .66 | .64 | .72 | .75 | .76 | ||||||

| 19. Mother-Report EB Kindergarten | .25 | .30 | .31 | .35 | .31 | .31 | .29 | .25 | |||||

| 20. Mother-Report EB Grade 1 | .32 | .32 | .36 | .41 | .39 | .39 | .34 | .33 | .76 | ||||

| 21. Mother-Report EB Grade 3 | .33 | .32 | .36 | .42 | .41 | .39 | .34 | .33 | .67 | .74 | |||

| 22. Mother-Report EB Grade 4 | .32 | .30 | .32 | .37 | .38 | .37 | .34 | .33 | .65 | .74 | .80 | ||

| 23. Mother-Report EB Grade 5 | .33 | .30 | .35 | .38 | .39 | .39 | .35 | .36 | .63 | .70 | .75 | .79 | |

| 24. Mother-Report EB Grade 6 | .37 | .28 | .32 | .38 | .40 | .36 | .34 | .36 | .62 | .67 | .72 | .75 | .80 |

Note: EB = Externalizing Behavior. Correlations > .10 in absolute value are significant at p < .0001. Descriptives for temperament, teacher–child conflict, and externalizing behavior are based on factor scores.

Unconditional Multivariate Growth Models

An unconditional growth model (i.e., without predictors) was estimated to examine average patterns of change and individual differences in trajectories in the three outcomes (teacher–child conflict, teacher–reported externalizing behavior, and mother-reported externalizing behavior). This model had excellent fit, χ2(159) = 527, p < .01, CFI = .98, RMSEA [90% CI] = .05 [.04, .05]. Teacher–child conflict exhibited a small but significant increase over time; the trajectory was nonlinear, with the largest increase occurring between kindergarten and grade 1 and a slower rate of increase thereafter. Teacher–reported externalizing behavior also showed a small but significant nonlinear increase, most of which occurred by grade 3. In contrast, mother-reported externalizing behavior exhibited a significant and mostly linear decline across grades. Significant individual differences in trajectories were observed for each outcome.

Conditional Multivariate Growth Models

Conditional multivariate growth models were estimated to test the hypotheses. In these models, between-person effects captured the direct and indirect effects of anger and effortful control on the intercept (i.e., predicted value at kindergarten) and slope factors (i.e., change across all grades) for each outcome. The within-person effects captured the direct relations between the outcome variables concurrently and from one grade to the next, controlling for individual differences in growth. Model A, in which temperament predicted externalizing behavior through teacher–child conflict, had excellent fit, χ2(235) = 832, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA [90% CI] = .05 [.04, .05], AIC = 33337, BIC = 33776; results are summarized in Table 2. Model B, in which temperament predicted teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior, also had excellent fit, χ2(237) = 793, p < .01, CFI = .97, RMSEA [90% CI] = .05 [.04, .05], AIC = 33294, BIC = 33723; results are summarized in Table 3. For complete estimates for both models, see Appendix A and B (Supplemental Information). For each model, we discuss the between-person relations, followed by the within-person relations.

Table 2.

Summary of results for Model A

| Intercept Factor | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Between-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Intercept Factor | ||||||

| Intercept Factor Mean | −0.22* | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.34* | 0.04 |

| Intercept Factor Variance | 0.41* | 0.02 | 0.20* | 0.01 | 0.35* | 0.02 |

| Direct Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| Anger | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.34* | 0.03 |

| Effortful Control (EC) | −0.14* | 0.03 | −0.05* | 0.02 | −0.22* | 0.03 |

| Girl vs. Boy | 0.20* | 0.04 | 0.12* | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.04 |

| Income-to-Needs Ratio | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Indirect Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| EC through Conflict Intercept | −0.17* | 0.03 | −0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Boy through Conflict Intercept | 0.23* | 0.05 | 0.09* | 0.02 | ||

| Relations Between Outcomes | ||||||

| Conflict Intercept | 1.16* | 0.04 | 0.45* | 0.06 | ||

| Conflict Slope | 0.44* | 0.06 | 0.26* | 0.07 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Slope Factor | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Between-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Slope Factor | ||||||

| Slope Factor Mean | 0.25* | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.46* | 0.04 |

| Slope Factor Variance | 0.29* | 0.02 | 0.18* | 0.02 | 0.27* | 0.03 |

| Direct Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| Anger | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.08* | 0.03 |

| Effortful Control (EC) | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Girl vs. Boy | 0.01 | 0.04 | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.08 | 0.05 |

| Income-to-Needs Ratio | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Indirect Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| EC through Conflict Intercept | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.03* | 0.01 | ||

| Boy through Conflict Intercept | 0.04* | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.02 | ||

| Relations between Outcomes | ||||||

| Conflict Intercept | 0.20* | 0.05 | 0.24* | 0.06 | ||

| Conflict Slope | 0.76* | 0.07 | 0.42* | 0.08 | ||

|

| ||||||

| Residuals | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Within-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Concurrent Relations | ||||||

| Grade K Conflict to Grade K EB | a0.72* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Grade 1 Conflict to Grade 1 EB | b0.54* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Grade 2 Conflict to Grade 2 EB | b0.54* | 0.02 | n/a | |||

| Grade 3 Conflict to Grade 3 EB | b0.54* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Grade 4 Conflict to Grade 4 EB | a0.72* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Grade 5 Conflict to Grade 5 EB | a0.72* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Grade 6 Conflict to Grade 6 EB | a0.72* | 0.02 | d0.07* | 0.02 | ||

| Cross-lagged Relations | ||||||

| Grade K Conflict to Grade 1 EB | −0.39* | 0.06 | e0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| Grade 1 Conflict to Grade 2 EB | c0.07* | 0.02 | e0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| Grade 2 Conflict to Grade 3 EB | c0.07* | 0.02 | n/a | |||

| Grade 3 Conflict to Grade 4 EB | c0.07* | 0.02 | e0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| Grade 4 Conflict to Grade 5 EB | c0.07* | 0.02 | e0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| Grade 5 Conflict to Grade 6 EB | c0.07* | 0.02 | e0.00 | 0.03 | ||

Note:

p < .01,

EST = estimate, SE = standard error, and K = Kindergarten. EC = Effortful Control and EB = Externalizing Behavior. Intercepts and slopes are latent variables. Only significant indirect effects are shown. Parameters with the same letter superscript are constrained to be equal.

Table 3.

Summary of results for Model B

| Intercept Factor | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Between-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Intercept Factor | ||||||

| Intercept Factor Mean | −0.24* | 0.03 | −0.08 | 0.04 | 0.30* | 0.04 |

| Intercept Factor Variance | 0.15* | 0.01 | 0.55* | 0.03 | 0.39* | 0.02 |

| Direct Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| Anger | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.36* | 0.03 |

| Effortful Control (EC) | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.21* | 0.03 | −0.28* | 0.03 |

| Girl vs. Boy | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.35* | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Income-to-Needs Ratio | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.08* | 0.03 | −0.06* | 0.02 |

| Indirect Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| EC through Teacher EB Intercept | −0.14* | 0.02 | ||||

| Boy through Teacher EB Intercept | 0.24* | 0.03 | ||||

| Relations Between Outcomes | ||||||

| Teacher EB Intercept | 0.67* | 0.03 | ||||

| Teacher EB Change | 0.09* | 0.04 | ||||

| Mother EB Intercept | 0.07 | 0.03 | ||||

| Mother EB Change | −0.06 | 0.04 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Slope Factor | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Between-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Slope Factor | ||||||

| Slope Factor Mean | 0.25* | 0.04 | 0.14* | 0.03 | −0.41* | 0.04 |

| Slope Factor Variance | 0.16* | 0.01 | 0.32* | 0.03 | 0.30* | 0.03 |

| Direct Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| Anger | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.08* | 0.03 |

| Effortful Control (EC) | −0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Girl vs. Boy | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.05 |

| Income-to-Needs Ratio | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.03 |

| Indirect Effects of Time-Invariant Predictors | ||||||

| EC through Teacher EB Intercept | 0.03* | 0.01 | ||||

| Boy through Teacher EB Intercept | −0.05* | 0.01 | ||||

| Relations Between Outcomes | ||||||

| Teacher EB Intercept | −0.13* | 0.03 | ||||

| Teacher EB Change | 0.45* | 0.04 | ||||

| Mother EB Intercept | −0.04 | 0.03 | ||||

| Mother EB Change | 0.11* | 0.05 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Residuals | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Within-Person Effects | T-C Conflict | Teacher EB | Mother EB | |||

|

|

|

|

||||

| EST | SE | EST | SE | EST | SE | |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

| Teacher EB: Concurrent Relations | ||||||

| Grade K EB to Grade K Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 1 EB to Grade 1 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 2 EB to Grade 2 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 3 EB to Grade 3 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 4 EB to Grade 4 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 5 EB to Grade 5 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 6 EB to Grade 6 Conflict | a0.45* | 0.01 | ||||

| Teacher EB: Cross-lagged Relations | ||||||

| Grade K EB to Grade 1 Conflict | 0.11* | 0.04 | ||||

| Grade 1 EB to Grade 2 Conflict | b−0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 2 EB to Grade 3 Conflict | b−0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 3 EB to Grade 4 Conflict | b−0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 4 EB to Grade 5 Conflict | b−0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 5 EB to Grade 6 Conflict | b−0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Mother EB: Concurrent Relations | ||||||

| Grade K EB to Grade K Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 1 EB to Grade 1 Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 3 EB to Grade 3 Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 4 EB to Grade 4 Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 5 EB to Grade 5 Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 6 EB to Grade 6 Conflict | c0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Mother EB: Cross-lagged Relations | ||||||

| Grade K EB to Grade 1 Conflict | d0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 1 EB to Grade 2 Conflict | d0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 3 EB to Grade 4 Conflict | d0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 4 EB to Grade 5 Conflict | d0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

| Grade 5 EB to Grade 6 Conflict | d0.02 | 0.01 | ||||

Note:

p < .01,

EST = estimate, SE = standard error, and K = Kindergarten. EC = Effortful Control and EB = Externalizing Behavior.

Intercepts and slopes are latent variables. Only significant indirect effects are shown. Parameters with the same letter superscript are constrained to be equal.

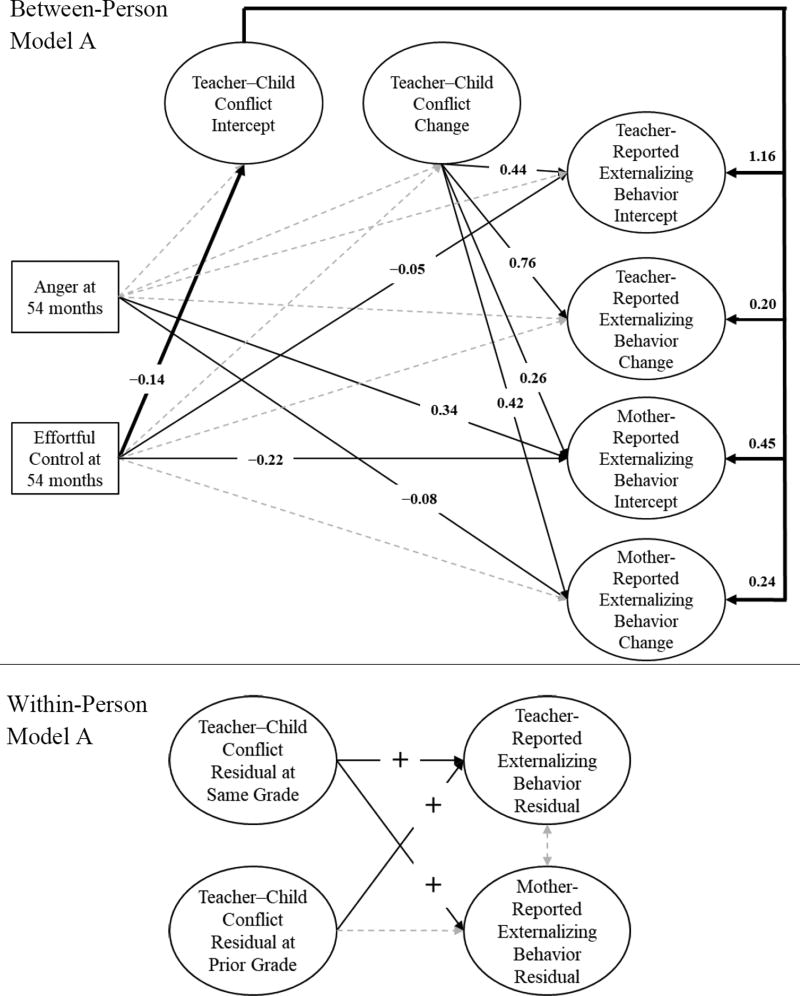

Model A: Between-person relations

The top panel of Figure 1 illustrates the between-person part of Model A. Significant effects are shown in solid black lines. More anger at 54 months predicted more mother-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten (i.e., the intercept factor), as well as a faster rate of decrease in mother-reported externalizing (i.e., the slope factor). However, anger did not predict the intercept or slope of either teacher-reported externalizing behavior or teacher–child conflict. Better effortful control at 54 months predicted lower kindergarten levels of teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior as reported by teachers and mothers; however, it did not predict the slope factor for any outcome.

Figure 1.

Between-person (top) and within-person (bottom) components of Model A. Nonsignificant direct effects are shown with dashed gray lines, significant direct effects are shown by solid black lines, and significant indirect effects are shown by heavy black lines. Within-variable covariances for growth factors were estimated and gender and income-to-needs were controlled (not shown). The within-person diagram is simplified and shows only the general pattern of ssociations across grades; the negative association between teacher-child conflict in kindergarten and teacher-reported externalizing behavior in first grade is omitted.

Turning to associations among the outcome variables, teacher–child conflict in kindergarten positively predicted teacher- and mother-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten (see Table 2). Higher levels of teacher-child conflict in kindergarten also predicted a faster increase in teacher-rated externalizing behavior and a slower decline in mother-rated externalizing behavior. Lastly, change in teacher–child conflict was positively related to change in teacher- and mother-rated externalizing behavior. Thus, children who increased more quickly in teacher–child conflict across grades also tended to increase more quickly in teacher-reported externalizing behavior and to decrease more slowly in mother-reported externalizing behavior.

Most important, there were significant indirect effects of effortful control on externalizing behavior through teacher–child conflict. These indirect effects are depicted in the top panel of Figure 1 by heavy black lines. Higher levels of effortful control at 54 months predicted lower levels of externalizing behavior in kindergarten through lower levels of teacher–child conflict in kindergarten. This indirect effect was found for both mother-reported and teacher-reported externalizing behavior. Additionally, effortful control indirectly predicted change in externalizing behavior. That is, effortful control predicted lower initial levels of teacher–child conflict, and lower initial levels of conflict predicted a faster rate of decrease in teacher-reported and mother-reported externalizing behavior. The four significant indirect effects of effortful control are shown in Table 2.

Model A: Within-person relations

The within-person portion of Model A examined relations between the residuals for teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior at the same grade and from one grade to the next. These effects can be interpreted as the relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior after accounting for individual differences in intercept and rate of change. For greater parsimony, these effects were constrained to be equal across grades when doing so did not decrease model fit (i.e., when there was a non-significant likelihood ratio test for nested models). Results are summarized in Table 2 and depicted in the bottom panel of Figure 1.

In each grade, greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict predicted greater-than-expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior in the same grade, as hypothesized. Furthermore, with one exception, greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict in each grade predicted greater than expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior in the next grade. The one exception was that greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict in kindergarten predicted lower than expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior in grade 1. Finally, greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict predicted greater-than-expected mother-reported externalizing behavior in the same grade; however, the lagged relation was not significant.

In summary, results for Model A indicated that child anger predicted initial levels of, and rates of change in, mother-reported externalizing behavior only, whereas effortful control predicted lower initial levels of teacher–child conflict, teacher-reported externalizing behavior, and mother-reported externalizing behavior. Furthermore, greater teacher–child conflict in kindergarten predicted greater externalizing behavior in kindergarten as well as change in externalizing behavior as reported by teachers and mothers. Most important, teacher–child conflict in kindergarten partially mediated the effects of effortful control on initial levels of and changes in externalizing behavior as reported by both teachers and mothers (four significant indirect effects). Within-person results showed that, with one exception, greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict in one grade predicted greater-than-expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior in that grade and the next grade (11 significant effects) as well as greater-than-expected mother-reported externalizing behavior in the same grade (five significant effects).

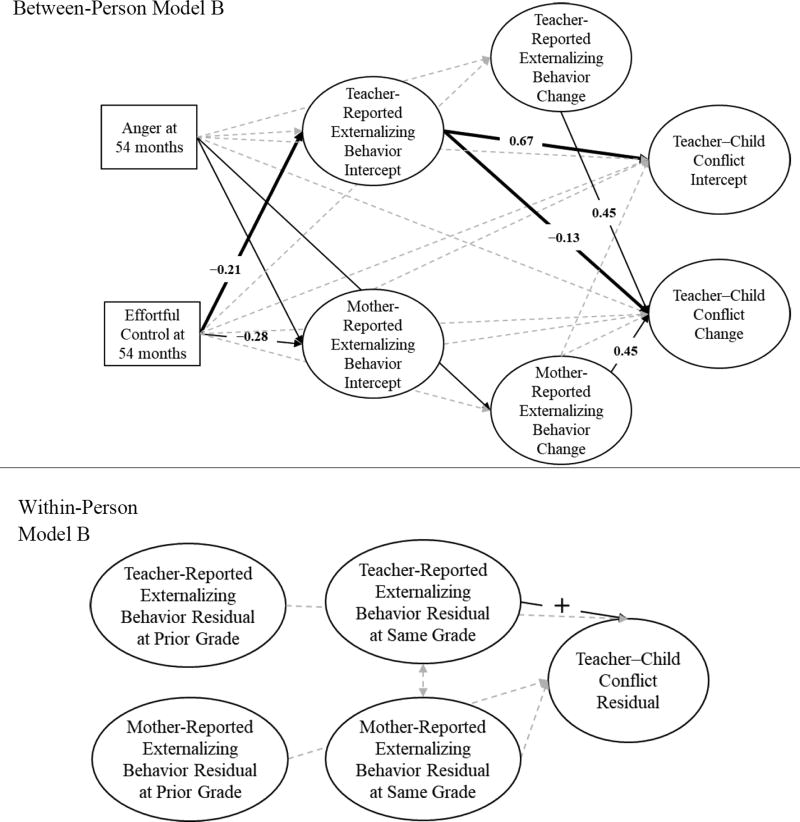

Model B: Between–person relations

An alternative predictive model (Model B) was estimated in which temperament traits predicted teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior. The top panel of Figure 2 illustrates the between–person portion of this model; significant effects are shown in solid black lines. The direct effects of the temperament variables were similar to those reported for Model A, except that effortful control at 54 months no longer predicted teacher–child conflict in kindergarten after controlling for externalizing behavior (see Table 3 for a summary of results).

Figure 2.

Between-person (top) and within-person (bottom) components of Model B. Nonsignificant direct effects are shown with dashed gray lines, significant direct effects are shown in solid black lines, and significant indirect effects are shown by heavy black lines. Within-variable covariances for growth factors were estimated and gender and income-to-needs were controlled (not shown). The within-person diagram is simplified and shows only the general pattern of associations across grades; the one significant cross-lagged association between teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten and teacher-child conflict in grade 1 is omitted.

Turning to relations among the outcome variables, more teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten predicted more teacher–child conflict in kindergarten (i.e., the intercept factor) and, counterintuitively, a slower increase in teacher–child conflict across grades (i.e., the slope factor). In contrast, mother-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten did not predict the intercept or slope of teacher–child conflict (see Table 3). The slope factors of externalizing behavior and teacher–child conflict were related: faster increases in both teacher-reported and mother-reported externalizing behavior predicted a faster increase in teacher–child conflict across grades.

Significant indirect effects are reported in Table 3 and depicted in the top panel of Figure 2 by heavy black lines. Effortful control predicted the intercept and slope of teacher–child conflict through teacher-reported externalizing behavior. That is, more effortful control predicted less teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten, and, in turn, less teacher-reported externalizing predicted less teacher–child conflict in kindergarten and, counterintuitively, a faster rate of growth in teacher–child conflict. In contrast, mother-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten did not mediate the effects of effortful control on teacher–child conflict.

Model B: Within-person relations

Results for the within-person portion of Model B appear in Table 3 and the bottom panel of Figure 2. Greater-than-expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior at each grade predicted greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict in the same grade. Furthermore, greater-than-expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten predicted greater-than-expected teacher–child conflict in grade 1; however, no other lagged effects were significant. The residuals for mother-reported externalizing behavior did not predict teacher–child conflict either concurrently or in the next grade.

In summary, results for Model B indicated that anger predicted initial levels of, and rates of change in, mother-reported externalizing behavior, whereas effortful control predicted lower levels of externalizing behavior in kindergarten as reported by both teachers and mothers. Greater teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten predicted greater teacher–child conflict in kindergarten but a slower increase in teacher–child conflict across grades. A faster increase in teacher-reported and mother-reported externalizing behavior predicted a faster increase in teacher–child conflict across grades. Teacher-reported externalizing behavior in kindergarten mediated the effects of effortful control on levels of and changes in teacher–child conflict, but mother-reported externalizing behavior did not. Regarding within-person effects, greater than expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior at each grade predicted greater than expected teacher–child conflict in the same grade, but the lagged relation was significant only from kindergarten to grade 1 (a total of seven significant effects).

Discussion

This study was designed to expand our understanding of how temperament shapes future externalizing behavior. To that end, we examined teacher–child conflict as a mediating variable between temperament traits and externalizing behavior, and explored the links between teacher–child conflict and child externalizing behavior across the elementary school years. Results indicated that teacher–child conflict partially mediated the effects of effortful control on levels of and changes in externalizing behavior as reported by both teachers and mothers. Furthermore, tests of within-person effects supported concurrent relations between teacher–child conflict and teacher- and mother-reported externalizing behavior, as well as cross-lagged relations between teacher–child conflict and teacher-reported externalizing behavior. An alternative model, in which temperament traits indirectly predicted teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior, received less consistent support. For both models, some results differed depending on whether externalizing behavior was reported by teachers or mothers.

Are Effects of Preschool Temperament Mediated by Teacher–Child Conflict?

The first study goal was to determine whether teacher–child conflict mediated the effect of preschool temperament traits on later externalizing behavior (Model A). This prediction was supported by significant indirect effects of effortful control. Children with higher levels of effortful control at age 54 months tended to have less teacher–child conflict in kindergarten; in turn, less teacher–child conflict predicted less externalizing behavior in kindergarten as well as a slower increase in teacher-reported externalizing, and a faster decrease in mother-reported externalizing, across grades (Table 2 and Figure 1). Indirect effects were observed whether externalizing behavior was rated by teachers or mothers, suggesting a robust effect. Our findings are consistent with prior research documenting the beneficial role of effortful control for positive social relationships and behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2001), as well as recent research showing associations between low effortful control and poor teacher–child relationship quality (Rudasill & Rimm-Kaufman, 2009; Valiente et al., 2012) and between teacher–child relationships and externalizing behavior (e.g., Doumen et al., 2008; Silver et al., 2010). Taken together, the findings suggest that children low in effortful control are less able to pay attention and control their behavior in classroom settings, leading to negative experiences with teachers that contribute to disruptive and aggressive behavior at school and at home. Thus one important way in which preschool effortful control appears to influence subsequent development is through its effect on early teacher–child conflict. However, effortful control also directly predicted externalizing behavior, so other processes may be involved as well.

The alternative causal sequence, in which effortful control indirectly predicted teacher–child conflict through externalizing behavior, also received partial support. In this case, more effortful control at age 54 months predicted less teacher-reported externalizing in kindergarten; in turn, less externalizing behavior predicted less teacher–child conflict in kindergarten but also, counterintuitively, a faster increase in teacher–child conflict from kindergarten to grade 6 (Table 3 and Figure 2). These results are largely congruent with previous findings showing that antisocial behavior increases the risk of negative teacher–child relationships (e.g., Birch & Ladd, 1998; Howes, Phillipsen, & Peisner-Feinberg, 2000), and raise the possibility that high effortful control limits the display of externalizing behavior, which then sets the stage for less teacher–child conflict. It is noteworthy, however, that this alternative model was supported only for teacher-reported externalizing behavior; the indirect effect of effortful control through mother-reported externalizing behavior was not significant.

In contrast to effortful control, indirect effects of temperamental anger were not found. Instead, preschool anger directly predicted levels of and changes in mother-reported externalizing behavior, consistent with some prior research (Olson et al., 2005). Interestingly, anger had no significant direct effects on teacher–child conflict or teacher-reported externalizing behavior in either model, even though the bivariate correlations were significant. Although some studies (e.g., Justice et al., 2008) have shown that temperamental anger predicts teacher–child conflict, our results indicate that anger does not substantially influence teacher–child conflict once effortful control is taken into account. Thus, in keeping with theoretical perspectives that emphasize the protective role of self-regulation for children with high levels of negative affectivity (Rothbart & Bates, 2006), effortful control may allow children high in anger to inhibit inappropriate classroom behavior and develop positive relationships with teachers.

Are There Reciprocal Effects of Teacher–Child Conflict and Externalizing Behavior?

Our results revealed more consistent support for teacher–child conflict predicting externalizing behavior than the converse. Between-person results showed that teacher–child conflict predicted levels of, and change in, externalizing behavior reported by both teachers and mothers. In contrast, only teacher-reported externalizing behavior predicted levels of, and change in, teacher–child conflict, and some of those effects were counterintuitive. Within persons, the concurrent relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior were significant at each grade level (regardless of reporter), and the lagged effects from teacher–child conflict in one grade to teacher-reported externalizing in the next grade were significant as well (see Table 2). Furthermore, the lagged effect controlled for prior levels of externalizing behavior, strengthening the case for a causal role of teacher–child conflict. In contrast, when teacher-reported externalizing was the predictor, the concurrent relations between teacher-reported externalizing behavior and teacher–child conflict were significant, but there was only one lagged effect (see Table 3). Thus, although reciprocal effects may occur within a single grade, as reported by Doumen et al. (2008), the primary pattern we observed across the elementary school years was one where teacher–child conflict in one year set the stage for higher than expected teacher-reported externalizing behavior the following year. This pattern is especially noteworthy because different teachers rated the children in different grades. The role of teacher–child relationships in subsequent externalizing behavior merits further attention.

Differences Between Reporters

As seen in other studies (Olson et al., 2005), there was evidence of reporter differences in ratings of children’s externalizing behavior. The bivariate associations between mother-rated and teacher-rated externalizing behavior were moderate at best, and in some cases results for the primary analyses differed by reporter. For example, effects of temperamental anger on externalizing were found only with mother-rated externalizing behavior, whereas effects of externalizing behavior on teacher–child conflict (Figure 2) and within-person associations between teacher–child conflict and subsequent externalizing (Figure 1) were found only with teacher-rated externalizing. These differences could reflect differences in the reporting context, as teachers observe children at school whereas mothers observe their children in multiple social contexts. Another possible explanation is reporter bias, which could inflate associations between mother reported variables (e.g., anger and externalizing) and between teacher-reported variables (e.g., teacher–child conflict and externalizing). For example, it is possible that a teacher who has developed a particular attitude towards a child rates the child’s behavior and the child’s relationship with her from this perspective, inflating the association between them. However, reporter bias cannot fully account for the present findings. First as noted earlier, there were some consistent effects of effortful control and teacher–child conflict on externalizing behavior regardless of reporter. Second, the lagged associations between teacher–child conflict in one grade and teacher-rated externalizing behavior in the next were not based on a single reporter but on teachers from different grades. Nonetheless, the differences between reporters underscore the importance of including multiple raters in future research on externalizing behavior.

These findings have significant implications for intervention. First, because poor effortful control is associated with more externalizing behavior (both directly and through greater teacher–child conflict), improving effortful control could be an important strategy for reducing externalizing behavior. Several classroom-based interventions have been designed to improve key components of children’s effortful control, attention and inhibitory control (e.g., Tools of the Mind: Diamond, Barnett, Thomas, & Munro, 2007; INSIGHTS: O’Connor, Cappella, McCormick, & McClowry, 2014). Both Tools of the Mind and INSIGHTS are based on an early intervention model in which children’s attention and inhibitory control skills are scaffolded and supported at the beginning of their educational trajectories. Evidence from randomized control trials with children in kindergarten and first grade suggests that INSIGHTS improves children’s attention which, in turn, improves their behavior and academic performance (O’Connor et al., 2014). Second, the concurrent and cross-lagged relations we observed between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior suggest that helping teachers improve their relationships with children may decrease externalizing behavior both concurrently and in the next grade. Such interventions are already available. In Banking Time, pre-school teachers spend 10–15 minutes in one-on-one child-directed interaction two to three times per week. Evidence from the first randomized control trial of Banking Time’s effectiveness demonstrated that teachers using Banking Time are significantly less negative and more positive during interactions with children than teachers in control conditions (Williford et al., 2015). Third, the positive associations we found between initial levels of teacher–child conflict and increases in externalizing behavior over the elementary school years suggest that intervening early to reduce teacher-child conflict may be especially beneficial for decreasing the likelihood of externalizing behaviors downstream.

Limitations and Future Directions

The findings should be viewed with several caveats in mind. First, although the SECCYD sample was diverse with respect to SES, average levels of mother’s education and family income-to-needs were relatively high from the outset, and there were relatively few minority children. Furthermore, there was higher attrition among non-White children, mothers without a college degree, and children from low income families resulting in a final sample that was somewhat more advantaged than the SECCYD as a whole. Therefore further research is needed to determine whether the effects found here hold for low SES children and for specific racial and ethnic groups. Second, although we examined reciprocal effects between teacher–child conflict and children’s externalizing behavior across multiple years, we could not test reciprocal effects within a school year. Future investigations are needed to tease apart reciprocal effects within versus across grades. Finally, the high associations between teacher–child conflict and teacher-reported externalizing behavior raise concerns about reporter bias. Including mother-reported externalizing behavior reduces this concern to some extent but not entirely, as mothers likely observe their children’s behavior across multiple contexts (e.g., home, community, and school), whereas teachers likely focus on behavior at school. In future studies it would be useful to include observer ratings of children in the classroom to minimize shared source effects.

Conclusions and Implications

Despite these limitations, the present study contributes uniquely to the existing literature on long-term effects of early temperament by documenting the role of teacher–child conflict as an intervening variable linking preschool effortful control to subsequent externalizing behavior and by testing for reciprocal effects between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior across the elementary school years. Our findings indicate that although temperamental anger is associated with externalizing behavior, effortful control plays a more substantial role in children’s development. Effortful control appears to limit externalizing behavior in part by reducing levels of teacher–child conflict in kindergarten which in turn slows growth in externalizing behavior across the elementary school years. Effortful control also contributes to lower teacher–child conflict by reducing children’s externalizing behavior, but these effects are less consistent. In addition, examination of within-person relations between teacher–child conflict and externalizing behavior over time provided stronger support for the effects of teacher–child conflict on subsequent externalizing behavior than the reverse. The findings point to the need for theoretical models of externalizing behavior that explicitly incorporate children’s temperament traits and their experiences in social contexts beyond the family, particularly at school. In terms of practice, efforts to provide teachers with knowledge about the importance of teacher–child relationships and skills to build positive relationships with children, especially those with poor effortful control and greater externalizing behavior, should be prioritized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R03HD077113 from NICHD to L. Crockett. Data came from the Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development, which was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) through a cooperative agreement (U10) that calls for scientific collaboration between NICHD staff and participating investigators.

Contributor Information

Lisa J. Crockett, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Alexander Michael Wasserman, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Kathleen Moritz Rudasill, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Lesa Hoffman, University of Kansas.

Irina Kalutskaya, University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4–18 and Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baker JA. Contributions of teacher–child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology. 2006;44:211–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. The interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the developmental of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–995. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch SH, Ladd GW. Children's interpersonal behaviors and the teacher–child relationship. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:934–946. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD. Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Howard AL, Bainter SA, Lane ST, McGinley JS. The separation of between-person and within-person components of individual change over time: A latent curve model with structured residuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82:879–894. doi: 10.1037/a0035297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePauw SSW, Mervielde I, Van Leeuwen KG. How are traits related to problem behavior in preschoolers? Similarities and contrasts between temperament and personality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:309–325. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9290-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, Barnett WS, Thomas J, Munro S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science. 2007;318:1387–1388. doi: 10.1126/science.1151148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumen S, Verschueren K, Buyse E, Germeijs V, Luyckx K, Soenens B. Reciprocal relations between teacher–child conflict and aggressive behavior in Kindergarten: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:588–599. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Cumberland A, Spinrad TL, Fabes RA, Shepard SA, Reiser M, et al. The relations of regulation and emotionality to children’s externalizing and internalizing problem behavior. Child Development. 2001;72:1112–1134. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Hyde JS, Goldsmith HH, Van Hulle CA. Gender differences in temperament: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:33–72. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AR, Taylor AR. The role of child gender and ethnicity in teacher–child relationship quality and children’s behavioral adjustment in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2009;24:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gartstein MA, Putnam SP, Rothbart MK. Etiology of preschool behavior problems: Contributions of temperament attributes in early childhood. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2012;33:197–211. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Aksan N, Essex M, Smider NA, Vandell DL. Temperament and socioemotional adjustment to kindergarten: A multi-informant perspective. In: Wachs TD, Kohnstamm GA, editors. Temperament in context. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 103–138. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre BK, Pianta RC. Early teacher–child relationships and the trajectory of children's school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development. 2001;72:625–638. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Melnick SM. Peer relationships in boys with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without comorbid aggression. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:627–647. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400006751. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman L. Longitudinal analysis: Modeling within-person fluctuation and change. New York: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Honomichl RD, Donnellan MB. Dimensions of temperament in preschoolers predict risk taking and externalizing behaviors in adolescents. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;3:14–22. doi: 10.1177/1948550611407344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C, Phillipsen LC, Peisner-Feinberg E. The consistency of perceived teacher–child relationships between preschool and kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:113–132. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(99)00044-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Justice LM, Cottone EA, Mashburn A, Rimm-Kaufman SE. Relationships between teachers and preschoolers who are at risk: Contribution of children’s language skills, temperamentally based attributes, and gender. Early Education and Development. 2008;19:600–621. doi: 10.1080/10409280802231021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]