Abstract

The number of older adults with cancer is growing, necessitating more collaborative training in both geriatric principles and cancer care. We administered a web-based survey to U.S. geriatrics program directors (PDs) addressing cancer-specific training and perspectives on optimal training content and roles for geriatricians in cancer care. Of 140 PDs contacted, 67 (48%) responded. Topics considered very important in training included cancer screening (79%) and cancer-related pain management (70%). Respondents strongly agreed that some of the geriatrician’s roles in cancer care included assessing functional status (64%) and assessing physical/cognitive function for goals of care (64%). About half (54%) agreed that having a standardized geriatric oncology curriculum overall was important. The presence of a geriatric oncologist, requiring cancer-based rotations, being affiliated with a cancer center, or being internal vs. family medicine-based did not affect this response. Despite this high level of support, cancer-related skills and knowledge warrant better definition and integration into current geriatrics training. This survey establishes potential areas for future educational collaborations between geriatrics and oncology training programs.

Keywords: Geriatric Oncology, Geriatric Fellowship, Training, Program Directors, Cancer Education

Introduction

By 2030, approximately two-thirds of patients with cancer will be 65 years and older (Smith, 2009; American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2014). Therefore, physicians will need training in how best to manage the increasing number of older adults with cancer (OACs) and aging-related risks such as frailty and multi-morbidity. Only 47% of hematology/oncology trainees in the U.S. report receiving at least one dedicated lecture on caring for OACs (Maggiore et al., 2014). In the United Kingdom, 66% reported no formal geriatric oncology training (Kalsi et al., 2013). In a survey of U.S. hematology/oncology fellowship program directors (PDs), 32% reported having a formal curriculum including geriatric oncology (Naeim et al., 2010). Nonetheless, most hematology/oncology trainees and PDs value geriatric oncology training (Maggiore et al., 2014; Naeim et al., 2010). Although these oncology fellowship-based studies provide some insight into the training knowledge gaps in the care of OACs, little is known about such training needs from geriatrics fellowship perspective. Ultimately, optimal health care delivery models for OACs will require collaborations between oncology and geriatrics, beginning with fellowship training.

Cancer is one of several comorbidities for which geriatrics fellows must demonstrate knowledge, but cancer care is not a mandatory component of their training, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) (2016). Approaches to integrating cancer care into geriatrics training programs may vary widely, thereby warranting further investigation into the current training environment. We performed a survey-based study of geriatrics PDs to query them about their: 1) current geriatrics fellowship training landscape related to the care of OACs; 2) perceptions of optimal roles for geriatricians in caring for OACs; and 3) attitudes about geriatrics fellowship training content related to the care of OACs. We also looked at whether various program factors were associated with the endorsement of a geriatric oncology curriculum.

Methods

Participants

Potential participants were PDs or associate PDs from ACGME-accredited U.S. geriatrics fellowship programs.

Measures

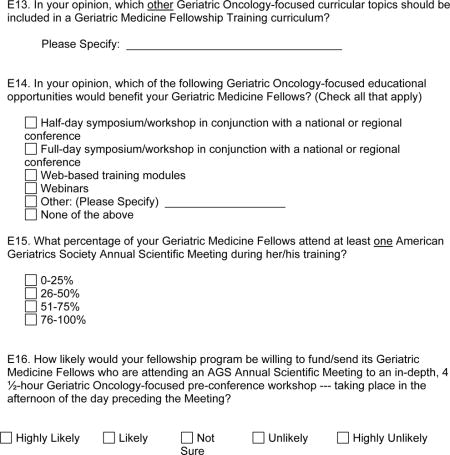

A modified Delphi process among a panel of U.S. geriatric oncologists affiliated with the Cancer and Aging Research Group (geriatricians, oncologists, and allied health professionals interested in geriatric oncology research) developed the survey items. Three rounds of reviews led to a consensus. The survey consisted of six sections (Appendix online).

1) demographics including years as program director (part A); 2) didactic and clinical experiences offered regarding care of OACs (parts B and C); 3) attitudes toward geriatric oncology principles in geriatrics fellowship training (parts D and E); and perceptions of geriatricians’ roles in caring for OACs (part F). A section for open-ended comments was provided.

Procedures

The American Geriatrics Society’s Fellowship Directors’ Committee provided email addresses of PDs/associate PDs of ACGME-accredited U.S. geriatrics fellowship programs (N=140 of 152 accredited programs). The survey was administered using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap™) software (Harris et al., 2009). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained with a waiver of written consent.

PDs received a short description of the study’s purpose, and were assumed to provide consent if they answered the survey. Potential respondents received the survey link by email, and two reminders, between May and December 2014.

Analysis

Responses were collectively organized by emerging themes rather than based on survey section. Data are presented as frequencies and percentages based on all responses, unless otherwise noted. Chi-square tests were utilized to compare whether (a) endorsement of a standard curriculum varied by four characteristics: presence of geriatric oncologist expert, mandatory geriatric oncology training experiences/rotations, cancer center affiliation, or program based in internal medicine vs. family medicine.A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was the threshold for statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SAS software (v 9.4, Cary, NC).

Results

Sixty-seven of the 140 potential respondents (48%) provided at least one response in all survey sections. Although e-mail addresses were not linked to these responses, the survey software allowed respondents to be tracked; as a result, these 67 respondents were from unique programs. Respondents were experienced PDs (about half with ≥6 years) and were mostly at academically oriented, internal medicine-based geriatrics fellowship programs with an affiliated cancer center (Table 1). Ten percent offered formal geriatrics-medical oncology fellowship training. Furthermore, 62% responded that collaborations between geriatrics and oncology divisions were “highly likely” or “likely” to support a geriatrics fellow interested in geriatric oncology.

Table 1.

Characteristics of survey respondents and representative programs (N=67).

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Years as Program Director/Associate Program Director | |

| 0–1 year | 9 (13) |

| 2 years | 9 (13) |

| 3–5 years | 15 (22) |

| 6–10 years | 22 (33) |

| >10 years | 12 (18) |

|

| |

| Sponsoring Department for Geriatrics Fellowship | |

| Internal Medicine | 45 (67) |

| Family Medicine | 21 (31) |

| Both | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Length of Geriatrics Fellowship Program(s) Offered | |

| 1 year | 63 (94) |

| 2 years | 21 (31) |

| 2 years with option of additional research years | 8 (12) |

|

| |

| Number of Fellowship Positions per Yeara | |

| 1–2 | 28 (44) |

| 3 | 12 (19) |

| 4 | 16 (25) |

| ≥5 | 8 (13) |

|

| |

| Formal geriatric oncology fellowship training pathway available | 7 (10) |

|

| |

| Affiliated with a cancer center or cancer program with clinical component | 63 (95) |

| Fellowship program likely or highly likely to collaborate with cancer centerb,c | 38 (62) |

| Presence of oncologist with expertise in geriatric oncologyb,d | 24 (39) |

| If present, does he/she provide education for geriatric fellowse | 14 (58) |

| If not present, who provides geriatric oncology education f | |

| Geriatric faculty | 22 (58) |

| No individual provides this content | 10 (26) |

| Other | 6 (16) |

|

| |

| Didactic Time Dedicated to the Care of OACg,h | |

| 0 | 6 (9) |

| <1 hour | 4 (6) |

| 1–3 hours | 31 (46) |

| 4–7 hours | 21 (31) |

| >7 hours | 5 (7) |

|

| |

| Clinical Experience Time Dedicated to the Care of OACh | |

| <2 hours | 19 (29) |

| 2–4 hours | 8 (12) |

| 5–12 hours | 11 (17) |

| 13–20 hours | 15 (23) |

| >20 hours | 12 (18) |

N=64; 3 participants missing

Among participants with a cancer center or cancer program with clinical component, N=63

N=61; 2 participants missing

N=62; 1 participant missing

Among participants with oncologist with expertise in geriatric oncology at cancer center, N=24

Among participants without oncologist with expertise in geriatric oncology at cancer center, N=38

N=65; 2 participants missing

OAC=Older adults with cancer

Three emergent themes arose within the responses for purposes of conceptually organizing and reporting the study data:

-

Current Geriatrics Fellowship Training Landscape Related to the Care of OACs

Most PDs reported having formal teaching addressing care of OACs, usually in lectures or seminars (81%). Other methods included readings or journal clubs (75%); case studies or conferences (55%); workshops (6%); and geriatric oncology modules from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)(1%). About 30% of programs dedicated 4-7 hours of instruction, while 46% dedicated 1-3 hours to teaching cancer care. Only 39% reported mandatory clinical experiences in cancer care for older adults, whereas 46% reported offering clinical electives in geriatric oncology. The time dedicated to clinical experiences in caring for OACs and formal teaching of geriatric oncology topics varied (Table 1). Several respondents reported in free-text comments that palliative medicine rotations were an opportunity for fellows to learn more about caring for OACs.

-

_Perceptions of Optimal Roles for Geriatricians Caring for OACs

The majority of respondents reported that geriatricians in general should serve in consultative as well as primary-care roles (92%), rather than as consultants alone (8%). Among free-text comments obtained, a few PDs pointed out the importance of geriatricians’ playing a role in primary palliative care (N=2); transitions of care including end-of-life care (N=2); primary care for OACs with dementia (N=1); and equal co-management of OACs throughout the cancer trajectory alongside the oncologist (N=5). More specifically, many PDs strongly agreed that optimal roles for geriatricians in care for OACs include: 1) determining functional status, as a consultant; 2) determining physical/cognitive status in context of goals of care; and 3) participating in cancer care decision-making when the geriatrician is the primary care provider (Table 2). Respondents felt geriatricians should assume more of a primary care provider role during active cancer therapy (67%), at completion of cancer therapy (79%), and when the patient is cancer-free for at least 5 years (89%). However, only 57% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that geriatricians’ roles included overseeing cancer surveillance and managing late-term effects of cancer therapy. Nearly all respondents thought geriatricians should be both primary care providers and consultants in caring for OACs, not just consultants (92% vs. 8%).

-

Attitudes about Geriatrics Fellowship Training Content Related to the Care of OACs

Most respondents agreed that geriatric oncology principles should be integrated in geriatrics fellowship training through a standardized curriculum (Table 2). Respondents’ attitudes toward a standardized geriatric oncology curriculum did not differ across programs based on presence of a geriatric oncologist expert (66.7% (yes) vs 47.4% (no/don’t know), p=0.14), mandatory formal geriatric oncology training experiences/rotations (60.0% (yes) vs. 52.5% (no), p=0.55), cancer center affiliation (56.5% (yes) vs. 57.5% (no), p=0.94), or internal medicine vs. family medicine (54.5% (internal) vs. 52.4% (family), p=0.87).Most respondents felt that screening and assessment skills for care of OACs were “very important” for fellows to learn (Table 3). Few PDs defined these areas in care of OACs as very important: assessing and managing cancer therapy-related adverse events; broadly understanding therapies for prevalent cancers in OACs; and utilizing cancer-focused geriatric assessment items.

Table 2.

Agreement with statements regarding geriatric oncology content and roles for geriatricians in the care of the older adult with cancer.

| % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | N | Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree |

| Geriatrics fellowship curriculum should: | ||||||

| Include geriatric oncology components | 66 | 26 | 51 | 15 | 6 | 1 |

| Be standardized to meet geriatrics fellow training needs | 66 | 21 | 33 | 29 | 15 | 2 |

|

| ||||||

| Geriatrician’s role in the care of the older adult with cancer: | ||||||

| Determining functional status as consultant | 66 | 64 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Determining physical and cognitive status in context of goals of care at the time of diagnosis | 64 | 64 | 33 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Participating in cancer care decision-making when geriatrician is the primary care provider | 66 | 58 | 33 | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Participating in developing a patient’s cancer survivorship plan with the oncologist | 66 | 33 | 53 | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| Being solely responsible for a patient’s primary care management during active cancer therapy | 66 | 20 | 47 | 18 | 14 | 1 |

| Being solely responsible for a patient’s primary care management upon completion of cancer therapy | 66 | 32 | 47 | 14 | 8 | 0 |

| Being solely responsible for a patient’s primary care when cancer-free for ≥5 years | 65 | 34 | 55 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| Being responsible for cancer-specific surveillance/monitoring of late-term cancer therapy-related adverse effects when cancer-free ≥5 years | 65 | 22 | 35 | 26 | 17 | 0 |

OAC = Older adults with cancer

Table 3.

Endorsed importance of geriatric oncology content.

| Item | N | Very Important | Important | % Neutral |

Somewhat Important | Not Important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer screening in older adults | 66 | 79 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess and manage cancer-related pain | 66 | 70 | 24 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Assess and optimize functional status in vulnerable older adults throughout cancer trajectory | 65 | 65 | 32 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess cognitive status in cancer care decision-making | 65 | 65 | 28 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess geriatric syndromes in cancer therapy decision-making | 65 | 62 | 32 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess geriatric syndromes in supportive care decision-making | 65 | 58 | 34 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess and optimize functional status in fit patients throughout cancer trajectory | 66 | 55 | 33 | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| Assess and manage psychological issues throughout cancer trajectory | 64 | 53 | 41 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Assess and manage comorbidities | 66 | 53 | 41 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Assess and manage cancer therapy-related adverse events | 64 | 41 | 42 | 11 | 5 | 1 |

| Broadly understand cancer therapies for most common cancers in older adults | 66 | 26 | 56 | 12 | 3 | 3 |

| Utilize cancer-focused comprehensive geriatric assessment instruments | 66 | 17 | 52 | 24 | 6 | 1 |

Discussion

Most respondents believe that cancer care and geriatric oncology principles are relevant to their trainees. However, formal didactic teaching or clinical experiences on this topic, although prevalent in our sample, vary widely. Many respondents stated they would support a standardized geriatric oncology curriculum, and such efforts have been reported (Eid et al., 2015). This survey’s results identified areas which geriatrics fellowship PDs identified as important for future geriatricians and their roles in care for OACs. These can be the foundation for collaborations between geriatrics and oncology educators, to determine common core competencies to benefit trainees from both fields, particularly since most of the programs reported being affiliated with a cancer center.

General challenges to collaborations between geriatrics and oncology fellowship programs include difficulties in scheduling clinical and didactic experiences, differences in training requirements, and the lack of formally accredited combined fellowship programs. These issues may partly explain underuse of extramural resources, such as ASCO’s online geriatric oncology modules. Such modules could provide didactic support for programs with more limited access to faculty or a cancer center.

This study highlights educational content and roles that geriatricians perceive as most important to support their care of OACs. This information is critical to designing education to support effective models of care. Respondents identified application of geriatric assessment findings (i.e., cognitive and functional status) and formulation of goals of care as key skills for optimal care of OACs. These areas of content overlap with unmet training needs in oncology fellowships. Hematology/oncology fellows in the U.K. identified geriatric assessment skills and recognizing geriatric syndromes that impact cancer therapy decision-making as areas where they needed improved training (Kalsi et al., 2013; Maggiore et al., 2014). These fellows receive less formal training in observation/feedback of functional assessment of OACs or end-of-life care discussions versus procedure-based, “traditional” oncology skills (e.g. bone marrow biopsies) (Buss et al., 2011; Maggiore et al., 2014).

Combined geriatrics and hematology/oncology training may allow geriatrics and hematology/oncology fellows to better learn from one another. For example, incorporating cognitive and functional assessments into care of OACs can be an opportunity for integrated, milestone-oriented training for geriatrics and hematology/oncology fellows, incorporated into ACGME-required training now in place. Other interdisciplinary care venues can foster improved training for both geriatrics and cancer trainees (Akthar et al., 2014). For example, tumor board conferences allow geriatricians and oncologists to collaborate and thereby influence shared cancer treatment decision-making for OACs (Blanc et al., 2014).

Many patients who use palliative medicine services are OACs. Since both geriatrics and medical oncology fellows must rotate through and attain competencies in palliative medicine, it may be a natural place to integrate geriatric oncology education. However, it is unclear to what extent geriatric oncology is covered during the palliative medicine experiences of geriatrics fellows, which can be affected by availability of resources (e.g., type of clinical setting) and other factors (Cao et al., 2015).

There was less consensus regarding the geriatrician’s role in managing cancer therapy-related adverse events or focusing curricular content on specific cancer therapies. Given the time constraints (usually one year of training) and specific requirements of geriatrics fellowship programs, there is likely little flexibility to add more cancer-based didactics or clinical experiences for these topics to be addressed. Alternatively, a co-management model may be more preferred by geriatricians in that some or all of these knowledge and skill-sets be delegated to the hematologist or oncologist specifically. This framework allows the geriatrician to focus more on “gero-centric” issues across the cancer care continuum, such as functional and cognitive issues to which the survey results appear to allude. Taken together, these data provide a framework for future collaborations between geriatrics and oncology educators to determine common core competencies for trainees.

The current study has limitations. The AGS fellowship directors’ committee list is representative of, but not entirely inclusive of, all active programs, and the contribution of program and program directors’ information is entirely voluntary. Not all intended recipients completed the survey, despite reminders. The most important limitation is potential response bias in interpreting survey results. The program directors who responded might inherently be more supportive of geriatric oncology education. To examine potential response bias, we used late responders (i.e., last quartile to complete) as a proxy for non-responders, a technique used in other studies (Kellerman & Herold, 2001), and compared them to the first quartile of respondents. Early and late survey responders did not significantly differ in ratings of importance of screening and assessment skills for care of OACs (data not shown) This lack of difference uggests that non-responders’ attitudes may not differ from survey responders. Importantly, our response rate is comparable to that in other survey-based studies; physician surveys have an average response rate of 54% (Asch, Jedrziewski, & Christakis, 1997), although specialist responses may be as low as 27% (Cunningham et al., 2015). Furthermore, non-response bias may not be as meaningful in physician surveys, based on the lack of significant differences between responders and non-responders in studies exploring this issue (Draugalis, Coons, & Plaza, 2008; Kellerman & Herold, 2001).

This is the first study to evaluate geriatrics fellowship program directors’ views on the current training landscape for geriatrics fellows regarding care of OACs, perceptions of geriatricians’ roles in such care, and their attitudes toward the training needs for delivery of such care. In this survey of geriatrics fellowship program directors, geriatric oncology principles were considered important for geriatrics fellows to learn. The new information gained from this study provides a foundation for educational programming that best meets the needs of future OAC care-providers. Future studies are required to develop a formal needs assessment for OAC care for geriatrics fellows. Furthermore, strategies in creating opportunities for collaborative education in geriatrics and hematology/oncology will continue to be needed.

Conclusion

Types of didactic and clinical resources for geriatrics fellows vary across programs regarding OAC care. Most respondents felt that geriatricians can serve specific roles within this context. Further studies are needed to determine consensus regarding (1) a geriatric oncology curriculum and (2) augmented educational resources relevant for trainees caring for OACs in their careers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Erin Obrusniak and members of the American Geriatrics Society for facilitating the development and conduct of this study. We also thank Karen Klein in the Wake Forest Clinical and Translational Science Institute (which is supported by UL1 TR001420; PI: King Li) for reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Funding Sources:

This research was supported by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of the Comprehensive Cancer Center of Wake Forest University (P30 CA012197, PI: Boris Pasche).

ONCOLOGY CURRICULAR CONTENT OF UNITED STATES-BASED GERIATRIC MEDICINE FELLOWSHIP TRAINING PROGRAMS

This survey should take approximately 5-10 minutes to complete. You may save answers and return at a later time to complete the survey if needed. Your participation is appreciated.

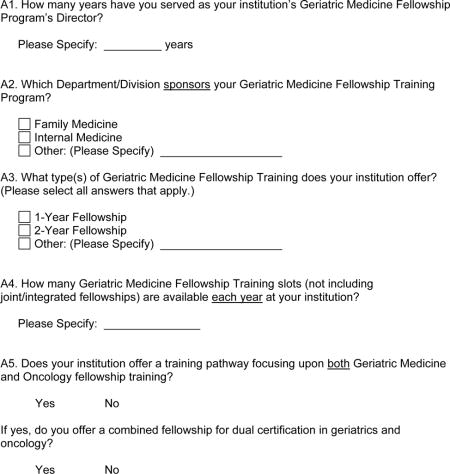

A. Geriatric Medicine Fellowship Training Program Profile

B. Geriatric Medicine Fellowship Training Program Oncology Curricular Content

The following questions are addressing training experiences of the geriatric medicine fellows in your program, excluding those fellows who are in a joint geriatric medicine/oncology program.

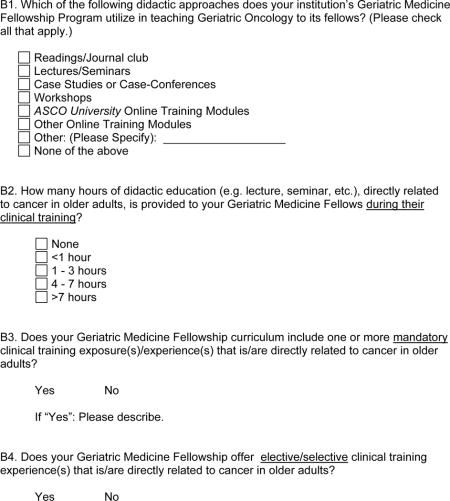

C. Oncology Program Status At Your Institution

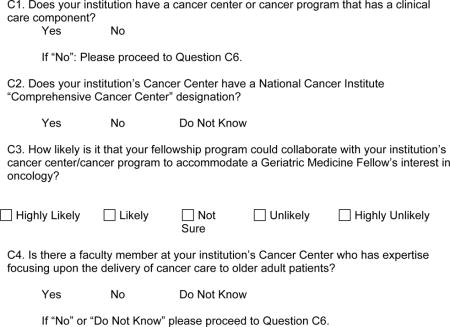

D. Oncology training in geriatrics fellowship

What is your level of agreement with regard to the following statements?

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1. Geriatric medicine fellowship training programs should include dedicated curricular components focusing upon Geriatric Oncology. | |||||

| D2. A standard curriculum should be established targeting the Geriatric Oncology training needs of Geriatric Medicine Fellows. |

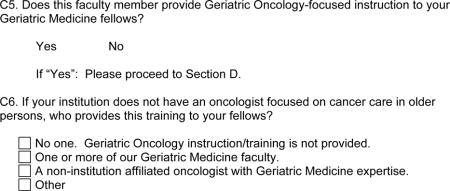

E. Curricular content regarding care of older patients in geriatrics training

How important is it to include the following topics in a Geriatric Medicine Fellowship Training curriculum?

| Very Important | Important | Neutral | Somewhat Important | Not Important | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1. Screening for common cancers of older adults. | |||||

| E2. Having a broad understanding of cancer therapies (e.g., curative vs. palliative intent, potential toxicities, goals of care) for treatment of common cancers in older adults (i.e., prostate, breast, colorectal, lung, lymphoma). | |||||

| E3. Assessing cognitive status within the framework of cancer care decision-making capacity. | |||||

| E4. Assessing for geriatric syndromes that may potentially impact cancer therapy decision-making. | |||||

| E5. Assessing for geriatric syndromes that may potentially impact cancer supportive care decision-making. | |||||

| E6. Utilizing cancer-focused Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment instruments. | |||||

| E7. Assessing and managing medical comorbidities throughout the patient’s cancer care. | |||||

| E8. Assessing and optimizing functional status in fit older adult patients throughout their cancer care trajectory. | |||||

| E9. Assessing and optimizing functional status in vulnerable older adult patients throughout their cancer care trajectory. | |||||

| E10. Assessing and managing cancer-related pain. | |||||

| E11. Assessing and managing adverse effects/events related to cancer therapy. | |||||

| E12. Assessing and managing psychological issues throughout the patient’s cancer care trajectory. |

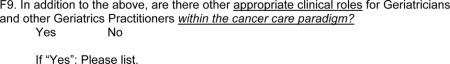

F. Clinical roles for geriatricians in the care of older cancer patients

What is your level of agreement with regard to appropriate clinical roles of Geriatricians and other Geriatrics Practitioners within the cancer care paradigm?

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1. Determining a patient’s functional status/“medical vulnerability” in a consultative role. | |||||

| F2. Determining a patient’s physical and cognitive function in relation to goals of care at the time of cancer diagnosis in a consultative role. | |||||

| F3. Participating in the cancer care treatment decision–making process when the Geriatrician is the physician-of-record of the cancer patient. | |||||

| F4. Participating in the development of a survivorship care plan for older adults with cancer (in conjunction with the hematologist/oncologist). | |||||

| F5. Being solely responsible for the patient’s primary care management during the patient’s active cancer care treatment. | |||||

| F6. Being solely responsible for the patient’s primary care management upon the completion of the patient’s active cancer care. | |||||

| F7. Being solely responsible for the primary care management of older adult cancer survivors who have been “cancer-free” for 5 years. | |||||

| F8. Being responsible for cancer disease-specific, tumor surveillance and the monitoring for cancer treatment-related adverse effects/events of older adult cancer survivors who have been “cancer-free” for 5 years. |

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest (disclosures table below). We affirm that this manuscript has not previously been published, nor has it simultaneously been submitted for review for publication at another journal.

Meetings: An abstract of this study was accepted and presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society on May 15, 2015.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Geriatric Medicine (Family Medicine or Internal Medicine) 2016 Feb 8; doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5552. (online). Retrieved from https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/125-151_geriatric_medicine_2016_1-YR.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Akthar AS, Ganai S, Hahn OM, Maggiore RJ, Cohen EEW, Posner M, Golden DW. Interdisciplinary oncology education: A survey of trainees and program directors in the United States. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(suppl) doi: 10.1007/s13187-016-1139-6. abstr e17617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) The State of Cancer in America, 2014. 2014 Mar 10; Retrieved from http://www.asco.org/practice-research/cancer-care-america.

- Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50(10):1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc M, Dialla O, Manckoundia P, Arveux P, Dabakuyo S, Quipourt V. Influence of the geriatric oncology consultation on the final therapeutic decision in elderly subjects with cancer: analysis of 191 patients. Journal of Nutrition, Health, and Aging. 2014;18(1):76–82. doi: 10.1007/s12603-013-0377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss MK, Lessens DK, Sullivan AM, Von Roenn J, Arnold RM, Block SD. Hematology/oncology fellows’ training in palliative care: Results of a national survey. Cancer. 2011;117(18):4304–4311. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Q, Lee TJ, Hayes SM, Nye AM, Hamrick I, Patil S, Steinweg KK. Are geriatric medicine fellows prepared for the important skills of hospice and palliative care? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care. 2015;32:322–328. doi: 10.1177/1049909113517050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, Jetté N. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BioMed Central Medical Research Methodology. 2015;15:32, 1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0016-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draugalis JR, Coons SJ, Plaza CM. Best practices for survey research reports: A synopsis for authors and reviewers. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2008;72(1):11. doi: 10.5688/aj720111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eid A, Hughes C, Karuturi M, Reyes C, Yorio J, Holmes H. An interprofessionally developed geriatric oncology curriculum for hematology-oncology fellows. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2015;6(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap™) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsi T, Payne S, Brodie H, Mansi J, Wang Y, Harari D. Are the UK oncology trainees adequately informed about the needs of older people with cancer? British Journal of Cancer. 2013;108:1936–1941. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician responses to surveys. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;20(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiore RJ, Dale W, Buss MK, Hurria A, Chapman AE, Dotan E, Mohile SG. Survey of geriatric oncology (geri onc) training among hematology/oncology (hem/onc) fellows. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32(suppl) doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.022111. abstr e20519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeim A, Hurria A, Rao A, Cohen H, Heflin M, Seo P. The need for an aging and cancer curriculum for hematology/oncology trainees. Journal of Geriatric Oncology. 2010;1(2):109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Smith GL, Hurria A, Hortobagyi GN, Buchholz TA. Future of cancer incidence in the United States: burdens upon an aging, changing nation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27(17):2758–2765. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]