Abstract

Event-based prospective memory (PM) refers to relying on environmental cues to trigger retrieval of a deferred action plan from long-term memory. Considerable research has demonstrated PM declines with increased age. Despite efforts to better characterize the attentional processes that underlie these decrements, the majority of research has relied on measures of central tendency to inform theoretical accounts of PM that may not entirely capture the underlying dynamics involved in allocating attention to intention-relevant information. The purpose of the current study was to examine the utility of the diffusion model to better understand the cognitive processes underlying age-related differences in PM. Results showed that emphasizing the importance of the PM intention increased cue detection selectively for older adults. Standard cost analyses revealed that PM importance increased mean response times and accuracy, but not differentially for young and older adults. Consistent with this finding, diffusion model analyses demonstrated that PM importance increased response caution as evidenced by increased boundary separation. However, the selective benefit in cue detection for older adults may reflect peripheral target-checking processes as indicated by changes in non-decision time. These findings highlight the use of modeling techniques to better characterize the processes underlying the relations among aging, attention, and PM.

Keywords: Prospective memory, Aging, Diffusion model, Attention, Older adults

Introduction

Event-based prospective memory (PM) refers to remembering and executing deferred intentions in response to external cues. PM failures have important health and societal implications, particularly with increased age. Researchers have therefore sought to better understand the attentional processes underlying PM intention retrieval and develop strategies to reduce often-observed age-related differences in laboratory-based tasks. In a typical PM task, a PM intention (e.g., “remember to press the ‘7’ key when you see the ‘tor’ syllable”) is embedded within the context of some other ongoing task (e.g., lexical decision task). Although considerable research has demonstrated that monitoring for the occurrence of PM cues produces cost to ongoing task performance (i.e., slower and/or less accurate responding) relative to when the same task is performed with no intention (Smith, Hunt, McVay, & McConnell, 2007), the cognitive processes that give rise to such effects are not well-characterized. Consequently, it is difficult to localize processes that may underlie age-related differences in cue detection. The current study therefore utilized a well-established cognitive process model (the diffusion model, described below) to better characterize the mechanisms governing successful PM in both young and older adults.

Prospective memory (PM) monitoring

Most contemporary theories of PM share the assertion that during tasks that require monitoring (termed nonfocal tasks), costs occur because both the ongoing and the PM task draw on the same limited attentional resources (Einstein & McDaniel, 2010; Smith et al., 2007). Consequently, as more resources are devoted to search or check the environment for cues, fewer resources are available for ongoing task processing (termed capacity sharing). As such, it is generally assumed that age-related differences in nonfocal cue detection are due to general declines in executive functioning associated with increased age (Zacks & Hasher, 1988), whereby older adults are less able to strategically allocate limited-capacity attentional resources to the PM task while simultaneously performing a demanding ongoing task (Rendell et al., 2007).

More recently, however, it has been suggested that costs may instead arise because the PM task races and competes for response selection with the more routine ongoing task, and to ensure that an ongoing task response is not made in lieu of a PM response, participants delay ongoing task responding to allow more time for PM evidence to accumulate (termed delay theory; Loft & Remington, 2013). That is, the delay theory posits that PM information (e.g., whether the stimulus contains the syllable tor) accrues in parallel with ongoing task information (e.g., stimulus lexicality) but at a slower rate, and so delaying ongoing task responding allows more time for PM information to accumulate and increases the likelihood of the appropriate response (e.g., “7” key) being selected. Age-related differences in cue detection may therefore instead occur because older adults do not appropriately increase their threshold for responding to allow sufficient processing time for the less frequent PM response to occur. However, it is not possible to arbitrate between these theoretical alternatives using traditional measures of central tendency (i.e., mean reaction time (RT)/accuracy), as different underlying mechanisms can produce similar costs. Consequently, researchers have recently turned to more formal modeling techniques to better characterize the mechanisms that underlie ongoing task cost.

Diffusion model

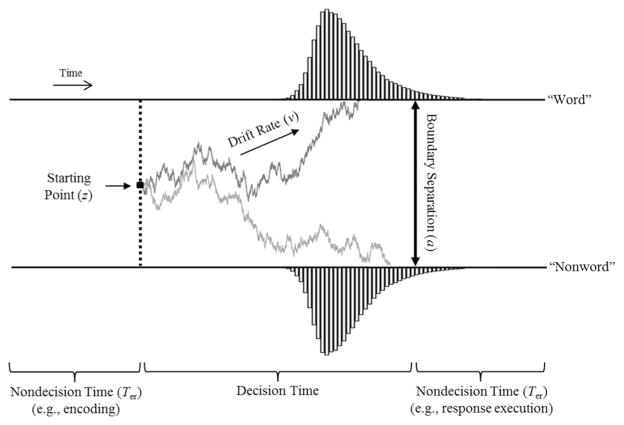

The diffusion model (Ratcliff, 1978) is a prominent cognitive process model that has been applied to accuracy and RT data from a variety of speeded decision tasks (for a review see Ratcliff & McKoon, 2008). This model assumes that the decision process (e.g., lexical decision) is based on the continuous accumulation of evidence from a starting point (z) toward one of two boundaries, and a decision (e.g., word or nonword) is made once a particular boundary is reached (see Fig. 1). The main parameters of the diffusion model include drift rate (v), boundary separation (a), nondecision time (Ter), and starting point (z).1

Fig. 1.

Major parameters of the diffusion model

Drift rate

The v parameter reflects processing efficiency (faster accumulation of evidence), and can be influenced by individual differences in the quality of information processing or stimulus characteristics that influence task difficulty. Higher values predict fast and accurate responses.

Boundary separation

The a parameter quantifies the distance between two boundaries and reflects the amount of information required to make a decision. Boundary separation is typically interpreted as response caution and is influenced by speed-accuracy instructions. Higher values predict slower RTs but more accurate responding.

Nondecision time

The Ter parameter reflects the duration of processes before and after the decision, such as stimulus encoding and motor response execution. Higher values predict slower RTs but produce no changes in accuracy.

Starting point

The z parameter is the starting point of evidence accumulation between the two boundaries. Starting point determines response bias (where unbiased responding corresponds to z = a/2) and is typically influenced by the relative frequency of presentation of different stimulus types (e.g., 75% words, 25% nonwords).

Diffusion modeling and PM

The application of diffusion modeling to PM tasks has provided interesting insights into the theoretical mechanisms that may underlie ongoing task costs. According to the capacity-sharing view of PM costs, monitoring for targets causes limited-capacity resources to be diverted from the ongoing task and therefore should slow evidence accumulation (drift) rates. Alternatively, delay theory posits that PM demands should produce changes in boundary separation because participants strategically increase response thresholds to allow more time for PM response selection to occur (Heathcote, Loft, & Remington, 2015). Lastly, Horn and Bayen (2015) suggested that PM demands may produce increases in nondecision time due to strategic checking of stimuli for intention-relevant details (i.e., target-checking) either prior to or following the ongoing task-decision process. It is important to note that although target-checking is attentionally demanding (Guynn, 2003), in the context of diffusion modeling it is considered to be a serial process occurring before/after the ongoing task decision and therefore should not slow response selection by diverting attention away from the ongoing task.2

Consistent with the delay theory, Heathcote et al. (2015) found that PM costs were associated with increases in boundary separation, rather than drift rates3 (see also Strickland, Heathcote, Remington, & Loft, 2017). Horn and Bayen (2015) similarly found that PM demands produced changes in threshold, but not drift rate, but additionally found that variables thought to influence the degree of monitoring enacted (i.e., importance of intention, cue frequency, and cue focality) selectively increased nondecision time. Together these results suggest that PM costs may reflect both response caution and target-checking, as indicated by changes in boundary separation and nondecision time, respectively, rather than decreased processing efficiency (i.e., drift rates).

PM, importance, and aging

The aforementioned findings have important implications for understanding age-related differences in cue detection. As described previously, it is generally assumed that PM decrements occur because older adults are less able, or less likely, to allocate limited-capacity attentional resources away from the ongoing task to support prospective remembering. Consistent with this idea, when the importance of the PM task (PM importance, or PMI) is emphasized, older adults are able to sacrifice ongoing task performance to produce comparable levels of cue detection to young adults (Hering et al., 2013; but see Smith & Hunt, 2014). Hering et al. suggested that the selective cue detection benefit for older adults in the PMI condition reflects that older adults may have “withdrawn part of the executive processing resources from the ongoing task to allocate them instead towards the fulfillment of the intended action” (p. 77), which would predict changes in the drift rate parameter had the authors implemented diffusion model analyses. However, Horn et al. (2013) found no evidence for processing efficiency differences between young and older adults during a standard nonfocal PM task (i.e., no importance manipulation), and Horn and Bayen (2015) found that PMI instructions selectively influenced nondecision time (with younger adults). Thus, it is possible that other processes (e.g., target-checking, response caution) may have contributed to the findings of Hering et al., and may underlie age-related cue detection differences more generally.

Current study

The current study examined the influence of importance on monitoring and cue detection in young and older adults. Participants performed an ongoing lexical decision task with a nonfocal intention (monitor for the “tor” syllable) and were either instructed that it was more important to detect all the PM cues (PMI condition), or that it was more important to do well on the ongoing task (ongoing task importance, or OTI, condition). Prior research with young adults has demonstrated that PMI instructions generally increase cue detection at the cost of ongoing task performance (Horn & Bayen, 2015; Loft et al., 2008). However, the influence of importance on PM in the context of aging is mixed, with one study showing a selective benefit in cue detection from PMI instructions for older adults (Hering et al., 2013), one showing a benefit for both age groups (Smith & Hunt, 2014), and one showing no effect for either age group (Kliegel, Martin & Moor et al., 2003). Smith and Hunt suggested that importance instructions may be more beneficial for older adults with an ongoing task that places relatively minimal demands on executive attention (e.g., a lexical decision task). We therefore expected that the increase in cue detection from PMI instructions would be greater for older adults. Importantly, we also expected any increase in cue detection following PMI instructions to come at a cost to ongoing task performance. If PMI instructions cause participants to allocate attention away from the ongoing task (Hering et al., 2013), this should be evidenced by changes in drift rate. Alternatively, if PMI instructions induce more cautious responding (Heathcote et al., 2015; Strickland et al., 2017) and/or increased target-checking (Horn & Bayen, 2015), the benefit in cue detection should be associated with changes in boundary separation and/or nondecision time, respectively.

Method

Participants

The participants included 70 younger adults (age 18–21 years) from Washington University who received course credit and 70 community dwelling older adults (age 60–90 years) who received monetary compensation for participation. Half the participants of each group were randomly assigned to the PMI or OTI condition. Participants that detected no PM cues and were unable to recall the PM instructions in a post-experimental questionnaire were excluded from all analyses (one young and ten older adults), as this reflects a failure of retrospective rather than prospective memory (Heathcote et al., 2015; Zimmerman & Meier, 2006). Additionally, one young and one older adult in each condition were excluded from analyses for having parameter estimates in the control and/or PM block greater than 3 standard deviations (SDs) from their respective groups mean. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information

| Young (PMI) | Young (OTI) | Older (PMI) | Older (OTI) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 34 | 33 | 29 | 29 | |

| Age | 19.2 (1.05) | 18.6 (1.95) | 76.0 (7.43) | 73.9 (8.07) | * |

| Education | 13.6 (.89) | 13.5 (.80) | 15.6 (2.68) | 16.0 (2.54) | * |

| Vocabulary | 27.8 (3.82) | 28.3 (3.24) | 30.2 (3.92) | 28.8 (4.70) | * |

Note. Each variable was submitted to a 2 (Age) × 2 (Condition) ANOVA, but there was no effect of condition or interaction of age and condition. Thus, the significance column refers to the main effect of age (e.g., older adults had higher vocab scores). Standard deviations are given in parentheses

Materials and procedure

For the lexical decision task, we selected 450 low-frequency English words (M = 5.42 occurrences per million, SD = .38) from the ELP database (Balota et al., 2007), and replaced one vowel from each word (e.g., pardon, chart) with another vowel to produce 450 pronounceable nonwords (e.g., parden, chirt). The computer program randomly selected for each participant one of the trial types (e.g., pardon, chirt) to be presented, meaning that the other trial type (e.g., parden, chart) would not be presented, with the stipulation that across the entire experiment 225 stimuli were words (e.g., pardon) and 225 items were nonwords (e.g., chirt). PM targets included eight low frequency words containing the “tor” syllable (e.g., vector). Each stimulus was randomly assigned to a trial position for each participant, and the eight PM cues were randomly assigned to trials 25, 50, 75, etc. through trial 200 in the PM block.

Participants completed a 30-trial practice phase, followed by a control (no intention) and PM (with intention) block (order was counterbalanced) each containing 210 LDT trials (50% words). Participants were to make lexical decisions as quickly and accurately as possible, after which a “waiting” message would appear to indicate that they should press the space bar to continue to the next trial. In the PM block, participants were additionally instructed to press the “7” key during the waiting message any time they encountered a word or nonword that contained the syllable “tor” (though “tor” only occurred in words). Critically, in the PMI condition participants were instructed that it was more important for them to detect every single “tor” syllable than it was for them to do well on the ongoing task, whereas in the OTI condition participants were instructed that it was more important for them to do well on the ongoing task than it was for them to detect every single “tor” syllable. Following intention encoding, participants performed the Shipley Vocabulary Test (Shipley, 1940) that lasted approximately 2 min. Participants performing the PM block first were instructed that the PM intention was no longer relevant prior to beginning the control block.

Ongoing task analyses

Standard reactions times (RTs)

The first five trials of each block, PM cue trials, and the three trials following cue presentation were excluded from analyses. Similar to Horn et al. (2013), we removed RTs faster than 350 ms or slower than 5,000 ms for older adults (2% of the data), and RTs faster than 300 ms or slower than 3,500 ms for younger adults (1% of the data). Subsequently, we excluded RTs greater than 3 SDs of each participant’s mean separately for each block (2% of the data for both age groups). Mean RT was then calculated for correct trials only, separately for each stimulus type (word/nonword) and block (control/PM). To control for age-related slowing, RTs were converted to within-participant z-scores based on the individual’s mean and SD (Faust, Balota, Spieler, & Ferraro, 1999). Analyses were averaged over stimulus type as lexical variables were not the focus of the study and conclusions do not differ whether or not stimulus type is included (Horn et al., 2013).

Diffusion model fitting

The diffusion model was fit to individual subjects’ data (described above, but including error trials) using maximum likelihood estimation implemented in fast-dm 30 (Voss, Voss, & Lerche, 2015). As we were primarily interested in how our manipulation differentially affected changes in mean parameter estimates from the control to the PM block, we fit 15 separate models of increasing complexity in which the main parameters (i.e., v, a, Ter, and z) were allowed to vary across blocks in isolation and then in combination up to and including all four of the major parameters. Additionally, drift rate was allowed to vary with stimulus type (i.e., words and nonwords) for all model variants (Ratcliff, Gomez, & McKoon, 2004). However, for mean level analyses drift rates were averaged over stimulus type as lexical variables were not the focus of the study and conclusions do not differ whether or not stimulus type is included (Horn et al., 2013). Lastly, we also estimated variability parameters (i.e., sv, sz, and st), but due to the relatively small number of trials we did not allow these parameters to vary as a function of block or stimulus type.

Participant level parameters from the best-fitting model were analyzed using ANOVA to test for group differences in model parameters as a function of age and importance instructions. To account for goodness of fit and parsimony, we selected the model with the smallest Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) index summed across participants (Myung & Pitt, 1997). As can be seen in Table 2, the best fitting model (Model 11) allowed boundary separation, nondecision time, and starting point, but not drift rate, to vary across blocks.4 Because the best fitting model did not allow drift rate to vary across blocks, there is only a single estimate for this parameter rather than having separate values for the control and PM blocks. Graphical fits for the best fitting model can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Table 2.

Diffusion model variants and corresponding Akaike Information Criteria

| Model | Varying by Block | K | ΣAIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | a | 9 | 38788 |

| 2 | Ter | 9 | 40180 |

| 3 | z | 9 | 43737 |

| 4 | v | 10 | 42074 |

| 5 | a, Ter | 10 | 38338 |

| 6 | a, z | 10 | 38468 |

| 7 | a, v | 11 | 38651 |

| 8 | Ter, z | 10 | 39917 |

| 9 | Ter, v | 11 | 39441 |

| 10 | z, v | 11 | 41700 |

| 11 | a, Ter, z | 11 | 38034 |

| 12 | a, Ter, v | 12 | 38206 |

| 13 | a, z, v | 12 | 38470 |

| 14 | Ter, z, v | 12 | 39264 |

| 15 | a, Ter, z, v | 13 | 38085 |

Note. K = number of model parameters per subject

Variability parameters were estimated but not allowed to vary across blocks. Drift rate was modeled separately for words and nonwords for all model variants

AIC Akaike Information Criteria, a boundary separation, Ter nondecision time, z starting point, v drift rate

Results

Cue detection

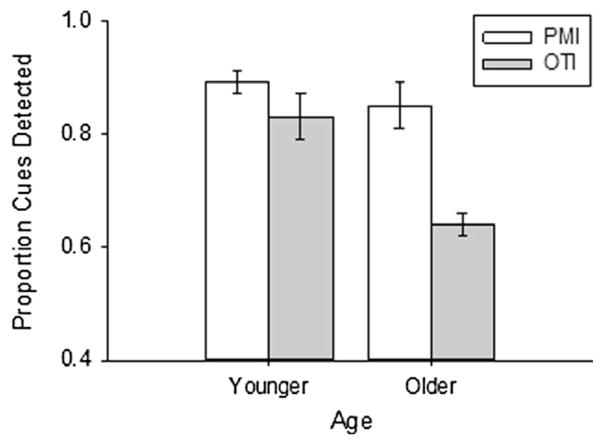

The proportion of PM cues successfully detected was submitted to a 2 (age: young, older) × 2 (condition: PMI, OTI) between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA). Cue detection was greater for young adults, F(1,121) = 7.96, p = .006, η2p = .062, and in the PMI condition, F(1,121) = 10.85, p = .001, η2p = .082. There was also a nominal age × condition interaction, F(1,121) = 2.94, p = .089, η2p = .024. Given the a priori predictions, follow-up analyses were conducted to examine the nature of the interaction effect. Planned comparisons revealed no cue detection differences between conditions for young adults, F(1,65) = 1.98, p = .163, η2p = .03, but greater cue detection for older adults in the PMI than OTI condition, F(1,56) = 8.51, p = .005, η2p = .132. As can be seen in Fig. 2, there were no age differences in the PMI condition, F(1,61) = 1.20, p = .278, η2p = .019, but better performance for young than older adults in the OTI condition, F(1,60) = 6.85, p = .011, η2p = .102.

Fig. 2.

Proportion of cues detected as a function of condition and age. PMI prospective memory performance, OTI ongoing task importance

Ongoing task performance

Ongoing task performance across each block is displayed in Table 3. Because possessing an intention produced significant increases in all ongoing task measures (including accuracy; all p < .05), the dependent variable for all analyses was the cost measure (PM block – control block). Each measure was submitted to a 2 (age: young, old) × 2 (condition: PMI, OTI) between-subjects ANOVA.

Table 3.

Ongoing task performance across blocks for young and older adults in each condition

| Block | Age | Cond | RT (ms) | ACC | a | Ter (ms) | z | v |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Young | PMI | 812 (23) | 0.86 (0.01) | 1.3 (0.05) | 525 (12) | 0.54 (0.01) | |

| OTI | 783 (16) | 0.87 (0.01) | 1.29 (0.05) | 518 (7) | 0.51 (0.02) | |||

| Older | PMI | 1240 (70) | 0.9 (0.01) | 1.92 (0.08) | 660 (24) | 0.52 (0.01) | ||

| OTI | 1215 (59) | 0.9 (0.01) | 1.93 (0.09) | 662 (21) | 0.56 (0.02) | |||

| PM | Young | PMI | 1000 (27) | 0.87 (0.01) | 1.73 (0.05) | 563 (13) | 0.56 (0.01) | 1.84 (.11) |

| OTI | 905 (27) | 0.87 (0.01) | 1.56 (0.06) | 543 (9) | 0.52 (0.01) | 1.92 (.09) | ||

| Older | PMI | 1610 (88) | 0.91 (0.01) | 2.65 (0.11) | 716 (31) | 0.54 (0.02) | 1.59 (.12) | |

| OTI | 1500 (76) | 0.9 (0.01) | 2.53 (0.11) | 663 (25) | 0.55 (0.01) | 1.67 (.11) | ||

| Cost | Young | PMI | 188 (18) | 0.012 (0.006) | 0.43 (0.05) | 38 (8) | 0.02 (0.01) | |

| OTI | 122 (18) | 0.004 (0.007) | 0.27 (0.05) | 25 (8) | 0.01 (0.01) | |||

| Older | PMI | 369 (35) | 0.011 (0.007) | 0.73 (0.07) | 56 (17) | 0.02 (0.01) | ||

| OTI | 286 (47) | 0.001 (0.006) | 0.6 (0.09) | 1 (15) | −0.01 (0.01) |

Note.

The selected diffusion model variant (the model with the lowest AIC index, described in the Method section) did not allow drift rates to vary across blocks, and therefore this value reflects drift rates across the entire ongoing task (i.e., there are not separate values for control and PM blocks)

RT reaction time, ms milliseconds, ACC accuracy, a boundary separation, Ter nondecision time, z starting point, v drift rate

Accuracy

Although participants were more accurate during the PM block, this did not differ as a function of age or condition, and there was no age × condition interaction, F’s < 2.33, p’s > .130.

Reaction time

Cost was greater for older adults, F(1,121) = 31.77, p < .001, η2p = .208, and in the PMI condition, F(1,121) = 5.97, p = .016, η2p = .047. The age × condition interaction was not significant, F < 1. Notably, after correcting for age-related slowing using z-transformed RTs (Faust et al., 1999), the effect of age was no longer significant, F < 1. However, cost was still greater in the PMI condition, F(1,121) = 11.23, p = .001, η2p = .088, and this did not differ by age, F < 1.

Together these results suggest a speed/accuracy tradeoff whereby possessing an intention resulted in slower but more accurate responding. However, PMI instructions and age only influenced RTs, and this latter finding was eliminated after correcting for age-related slowing.

Diffusion model analyses

As described in the Method section and as can be seen in Table 1, the best-fitting model (Model 11) allowed boundary separation, nondecision time, and starting point, but not drift rate, to vary across blocks (i.e., control and PM). Thus, sub-sequent analyses are performed on the cost measure (PM block – control block) for all diffusion model parameters except for drift rate, which instead is performed on the overall drift rate. Each measure was submitted to a 2 (age: young, old) × 2 (condition: PMI, OTI) between-subjects ANOVA.

Drift rate

Overall drift rate was slower for older adults, F(1,121) = 5.64, p = .019, η2p = .045. However, there was no effect of condition, and no age × condition interaction, F’s < 1.

Boundary separation

Cost was greater for older adults, F(1,121) = 24.14, p < .001, η2p = .166, and in the PMI condition, F(1,121) = 5.08, p = .026, η2p = .04. The age × condition interaction was not significant, F < 1.

Nondecision time

Cost was similar between age groups, F < 1, but greater in the PMI condition, F(1,121) = 7.53, p = .007, η2p = .059. There was also a nominal age × condition significance, F(1,121) = 2.88, p = .09, η2p = .023, such that there was no cost difference between conditions for young adults, F(1,65) = 1.30, p = .258, η2p = .02, but a greater cost for older adults in the PMI than the OTI condition, F(1,56) = 5.63, p = .021, η2p = .091.

Starting point

Cost did not differ across age groups or conditions, and there was no interaction between the two, F’s < 2.04, p’s > .158.

In summary, possessing an intention produced slower but more accurate responding, and diffusion model analyses suggested that this cost was due to increases in both boundary separation and nondecision time during the PM block. PMI instructions produced an increased RT cost for both age groups, which was largely due to increased boundary separation. Additionally, PMI instructions increased nondecision time cost for older but not younger adults. This latter finding is consistent with the influence of PMI instructions on cue detection.

Functional cost analyses

To examine the functional role of monitoring on cue detection, we examined the relation between diffusion model cost measures and successful PM detection. As can be seen in in Table 4, only boundary separation and nondecision time cost were predictive of cue detection. However, these cost measures were not correlated with one another, suggesting functionally independent processes.

Table 4.

Correlations between cue detection and cost measures

| PM | ACC | RT | RTz | a | Ter | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM | 1.00 | ||||||

| ACC | −.13 | 1.00 | |||||

| RT | .17 | −.10 | 1.00 | ||||

| RTz | .35** | −.17 | .73** | 1.00 | |||

| a | 0.18* | −.11 | .80** | .75** | 1.00 | ||

| Ter | .25** | −.05 | .36** | .36** | −.04 | 1.00 | |

| z | .13 | −.24** | .15 | .29** | .15 | .30** | 1.00 |

Note.

p < .01,

p < .05

PM cue detection, ACC ongoing task accuracy, RT reaction time, RTz z-transformed reaction time, a boundary separation, Ter nondecision time, z starting point

We performed a hierarchical regression analysis to examine whether these cost measures account for significant variability in cue detection beyond age. As can be seen in Table 5, in Step 1 age accounted for 6% of the variance in PM. Including the diffusion model cost measures of boundary separation and nondecision time increased the explained variance (21%), F(2,121) = 11.47, p < .001, and both uniquely predicted performance.

General discussion

Prior research suggests that one reason that older adults typically do worse in laboratory-based PM tasks is that they are less likely, or able, to divert limited-capacity attentional resources away from ongoing task processing to support prospective remembering. Hering et al. (2013) provided support for this notion, showing that emphasizing the importance of the PM intention produced a selective benefit for older adults at a cost to ongoing task performance. The results from the current study demonstrated a very similar pattern for older adults in terms of cue detection and RT cost. Diffusion model analyses, however, suggested that costs were not due to allocating attention away from the ongoing task, as would be indicated by a slowing of evidence accumulation (i.e., drift) rates. Rather, costs were a result of increased boundary separation and nondecision time. As described previously, these costs are thought to reflect increased response thresholds to allow more time for PM selection to occur as well as target-checking processes either prior to or following the decision process (Heathcote et al., 2015; Horn & Bayen, 2015). Interestingly, both boundary separation and nondecision time uniquely predicted cue detection, suggesting functionally independent processes that may facilitate prospective remembering.

Interestingly, overall there was a greater increase in boundary separation during the PM block for older than for young adults. This suggests that the metacognitive assessment of perceived task difficulty of the dual-task demands in the PM block may be greater for older than for young adults, thereby leading to a greater threshold for ongoing task responding (Horn & Bayen, 2015; see Starns & Ratcliff, 2010 for evidence that older adults do not optimally adjust thresholds to task demands). Alternatively, it may be that for older adults PM evidence accumulates more slowly, or more evidence is required to make a PM response, and therefore they adopt a more conservative decision threshold to ensure that the ongoing task decision is not made prior to PM response selection (Heathcote et al., 2015; Strickland et al., 2017). An interesting avenue for future research to examine this possibility would be to use a three-accumulator model to examine parameter estimates for PM responses (which is not possible with diffusion modeling and small PM trial counts).

Importantly, the selective benefit to cue detection in the PMI condition for older adults does not necessarily appear to be due to increases in boundary separation, as both young and older adults similarly increased response thresholds following PMI instructions, but only older adults increased cue detection. In contrast, while there was no nondecision time cost difference for young adults, there was greater cost for older adults in the PMI than the OTI condition. These findings suggest that the cue detection differences observed by older adults may be due to increased target-checking processes that were implemented by older adults in the PMI condition. Thus, rather than the traditional assumption that older adults are less able to divert attention resources from the ongoing task, it may be that typical age-related declines in cue detection reflect that older adults less effectively engage target checks to support prospective remembering. This interpretation is generally consistent with extant theories of PM costs (Guynn, 2003; Einstein & McDaniel, 2010; Smith et al., 2007) and age-related differences in cue detection (Rendell et al., 2007). However, we suggest that rather than older adults having difficulty in diverting attention away from the ongoing task, we suggest that executive attention deficits may preclude efficient engagement of an additional process (i.e., target check) either prior to or following the ongoing task decision.

More generally, the current study extends previous finding by demonstrating threshold increases when participants were instructed to make their PM response following, rather than instead of (Heathcote et al., 2015; Horn & Bayen, 2015), their lexical decision. It could be argued that increasing response thresholds may be less useful in this scenario, as participants could presumably remember the PM response during the intertrial (“waiting”) interval. These findings suggest that regardless of when the PM response can be executed, allowing greater time for processing of PM stimulus features by increasing thresholds may reduce PM errors. It should also be noted that although PM demands produced a considerably greater effect on nondecision time than boundary separation in terms of overall RT cost, target-checking has been described as a transient process that is not necessarily enacted on each trial (Ball, Brewer, Loft, & Bowden, 2015; Guynn, 2003) and therefore should theoretically produce smaller effects in overall mean estimates. While this interpretation is consistent with Horn and Bayen (2015), Heathcote et al. (2015) failed to find effects of PM demands on nondecision time using LBA. Future research should therefore aim to distinguish whether these differences in results are due to task influences or idiosyncrasies of the specific models used to describe the data.

In conclusion, the results from the current study suggest PMI instructions may facilitate target-checking for older adults. However, it is likely that other manipulations shown to reduce age-related cue detection differences (e.g., implementation intentions) may produce changes in monitoring that influence different parameters. Thus, future research implementing formal modeling techniques may provide a more complete picture of monitoring and cue detection differences across the lifespan that may be beneficial for targeting specific cognitive processes to facilitate performance.

Supplementary Material

Table 5.

Hierarchical regression predicting cue detection

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01

a boundary separation cost, Ter nondecision time cost

Acknowledgments

Author Notes B.H.B. was supported by an NIA Training Grant (T32AG000030-40). We thank Samantha Breen, Whitney Dominguez, and Erin Gourley for their assistance in data collection.

Footnotes

The diffusion model also has three variability parameters (though typically not of psychological interest), including across-trial variability in drift rate (normal distribution with standard deviation η), starting point (uniform distribution with range sz), and nondecision time (uniform distribution with range st).

The target-checking mechanism is actually derived from capacity sharing views of PM costs (see Guynn, 2003) and could theoretically occur in parallel with, or before/after, the ongoing task-decision process. However, in the context of diffusion modeling, target-checking has primarily been described as a serial process that should influence nondecision time (rather than drift rates) based on empirical findings (Horn & Bayen, 2015).

Heathcote et al. (2015) fit the linear ballistic accumulator (LBA) model to PM costs. The LBA is a prominent evidence accumulation model conceptually similar to the diffusion model in regard to the main parameters of the model (i.e., drift rate, boundary separation, nondecision time, and starting point).

We also calculated Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) indices for each model. Although the philosophical underpinnings of AIC and BIC indices differ, the practical implication for the present purposes is that the BIC model penalizes more for model complexity and thus will often only be sensitive to the strongest effects unless there is high power (Burnham & Anderson, 2004). The BIC favored a model in which only boundary separation varied across blocks, which is consistent with the finding from the AIC-favored model in which boundary separation was the largest contributor to PM cost. Importantly, analysis of boundary separation from the BIC model was identical to that reported from the AIC model. AIC and BIC values for each model variant, as well as graphical fits for the best fitting model, can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.3758/s13423-017-1318-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- Ball BH, Brewer GA, Loft S, Bowden V. Uncovering continuous and transient monitoring profiles in event-based prospective memory. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2015;22(2):492–499. doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0700-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balota DA, Yap MJ, Hutchison KA, Cortese MJ, Kessler B, Loftis B, … Treiman R. The English lexicon project. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(3):445–459. doi: 10.3758/bf03193014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociological Methods & Research. 2004;33(2):261–304. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein GO, McDaniel MA. Prospective memory and what costs do not reveal about retrieval processes: A commentary on Smith, Hunt, McVay, and McConnell (2007) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, & Cognition. 2010;9:147–162. doi: 10.1037/a0019184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust ME, Balota DA, Spieler DH, Ferraro FR. Individual differences in information-processing rate and amount: Implications for group differences in response latency. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(6):777. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guynn MJ. A two-process model of strategic monitoring in event-based prospective memory: Activation/retrieval mode and checking. International Journal of Psychology. 2003;38:245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote A, Loft S, Remington RW. Slow down and remember to remember! A delay theory of prospective memory costs. Psychological Review. 2015;122(2):376. doi: 10.1037/a0038952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering A, Phillips LH, Kliegel M. Importance effects on age differences in performance in event-based prospective memory. Gerontology. 2013;60(1):73–78. doi: 10.1159/000355057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS, Bayen UJ. Modeling criterion shifts and target checking in prospective memory monitoring. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2015;41(1):95–117. doi: 10.1037/a0037676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn SS, Bayen UJ, Smith RE. Adult age differences in interference from a prospective-memory task: A diffusion model analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2013;20(6):1266–1273. doi: 10.3758/s13423-013-0451-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliegel M, Martin M, Moor C. Prospective memory and ageing: Is task importance relevant? International Journal of Psychology. 2003;38(4):207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Loft S, Kearney R, Remington R. Is task interference in event-based prospective memory dependent on cue presentation? Memory & Cognition. 2008;36(1):139–148. doi: 10.3758/mc.36.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loft S, Remington RW. Brief delays in responding reduce focality effects in event-based prospective memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2013;66:1432–1447. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2012.750677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung IJ, Pitt MA. Applying Occam’s razor in modeling cognition: A Bayesian approach. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 1997;4(1):79–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R. A theory of memory retrieval. Psychological review. 1978;85(2):59. [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, McKoon G. The diffusion decision model: Theory and data for two-choice decision tasks. Neural Computation. 2008;20(4):873–922. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliff R, Gomez P, McKoon G. A diffusion model account of the lexical decision task. Psychological review. 2004;111(1):159. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendell PG, McDaniel MA, Forbes RD, Einstein GO. Age-related effects in prospective memory are modulated by ongoing task complexity and relation to target cue. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2007;14:236–256. doi: 10.1080/13825580600579186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley WC. A self-administering scale for measuring intellectual impairment and deterioration. The Journal of Psychology. 1940;9:371–377. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Hunt RR. Prospective memory in young and older adults: The effects of task importance and ongoing task load. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2014;21(4):411–431. doi: 10.1080/13825585.2013.827150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RE, Hunt RR, McVay JC, McConnell MD. The cost of event-based prospective memory: Salient target events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2007;33(4):734. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.33.4.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starns JJ, Ratcliff R. The effects of aging on the speed–accuracy compromise: Boundary optimality in the diffusion model. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25(2):377. doi: 10.1037/a0018022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strickland L, Heathcote A, Remington RW, Loft S. Accumulating evidence about what prospective memory costs actually reveal. Journal of experimental psychology. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 2017 doi: 10.1037/xlm0000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss A, Voss J, Lerche V. Assessing cognitive processes with diffusion model analyses: A tutorial based on fast-dm-30. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6:336. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacks RT, Hasher L. Capacity theory and the processing of inferences. Language, Memory, and Aging. 1988:154–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann TD, Meier B. The rise and decline of prospective memory performance across the lifespan. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2006;59(12):2040–2046. doi: 10.1080/17470210600917835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.