Abstract

Lassa virus (LASV) is responsible for an acute viral hemorrhagic fever known as Lassa fever. Sequence analyses of LASV proteome identified the most immunogenic protein that led to predict both T-cell and B-cell epitopes and further target and binding site depiction could allow novel drug findings for drug discovery field against this virus. To induce both humoral and cell-mediated immunity peptide sequence SSNLYKGVY, conserved region 41–49 amino acids were found as the most potential B-cell and T-cell epitopes, respectively. The peptide sequence might intermingle with 17 HLA-I and 16 HLA-II molecules, also cover 49.15–96.82% population coverage within the common people of different countries where Lassa virus is endemic. To ensure the binding affinity to both HLA-I and HLA-II molecules were employed in docking simulation with suggested epitope sequence. Further the predicted 3D structure of the most immunogenic protein was analyzed to reveal out the binding site for the drug design against Lassa Virus. Herein, sequence analyses of proteome identified the most immunogenic protein that led to predict both T-cell and B-cell epitopes and further target and binding site depiction could allow novel drug findings for drug discovery field against this virus.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1106-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Lassa fever, Docking simulation, Vaccine design, Binding site, Drug design

Introduction

Lassa virus (LASV) includes Arenaviridae virus family which causes Lassa fever (LF) disease. LASV is transmitted to human by a rodent named Mastomys natalensis. LASV is responsible for fatal hemorrhagic fever due to its capability to infect the highest number of people including 100,000–300,000 and 5000–10,000 annual deaths in western Africa. There is no licensed vaccine invented against Lassa virus yet. Carrying on research to develop vaccine is becoming cost effective due to non-human primate models and biocontainment requirements (BSL-4) (McCormick and Fisher 2002; Khan et al. 2008; Fichet-Calvet and Rogers 2009; Richmond and Baglole 2003; Loureiro et al. 2011; Charrel and de Lamballerie 2003). There are different areas assuming to be affected by Lassa fever, such as 10% of Ghana, 30% of each of Côte d’Ivoire, Togo and Benin, 40% of Nigeria, 50% of Guinea, 80% of Sierra- Leone and Liberia (Fichet-Calvet and Rogers 2009) and a few areas of Mali (Safronetz et al. 2010). About 200 million people of West Africa like Nigeria and Senegal are at high risk for outbreak of LASV (Charrel and de Lamballerie 2003). Sometimes North America, Europe and Japan revealed the existence of LASV. There are some viruses responsible for hemorrhagic fever such as Ebola, LASV and Marburg virus. Among them LASV is the most frequently imported virus by returning travelers (Wolfe and Macher 2006; Gunther et al. 2001; Schmitz et al. 2002). Many areas of Europe such as Germany (Haas et al. 2003; Gunther et al. 2000), Netherlands (Weekly epidemiological record 2000) and the United Kingdom (Communicable disease report CDR weekly 2000) are affected by imported LASV. Some vaccination processes like immunization with inactivated LASV showed nearly no efficacy. Therefore, it is urgent to develop an efficient vaccine with a view to repel an extreme outbreak of this disease.

Epitope or peptide based vaccine is more eligible than the conventional vaccines due to its easy production, more specificity, and also safety. Two types of proteins are found in a virus. One is found in its surface and another is secreted from that virus. Both of them are antigenic and pathogenic (Hasan et al. 2015; Cerdino-tarraga et al. 2003). So, they are considered for vaccination. Portions of these proteins bind with antibodies as they are recognized as antigenic. The identification of B-cell epitope is required to design vaccine (Larsen et al. 2006a, b). Specific binding of Antigen to HLA alleles (MHC-I and MHC-II) might induce an effective immune response (Kuhns et al. 1999; Watts 1997; Germain 1994).

Recently, several bioinformatics tools and servers are being used to predict both B-cell and T-cell epitopes precisely. Researchers tried to develop the way by in silico studies for the advancement of better medication against cancer and autoimmune diseases by predicting candidate antigens from which they could propose the suitable epitopes for vaccination. (Hammer et al. 1995; Saha and Raghava 2006; Segal et al. 2008; Stassar et al. 2001). This approach of vaccine designing is used in a long range to defeat many diseases such as multiple sclerosis (Bourdette et al. 2005) malaria (Lopez et al. 2001) and tumors (Knutson et al. 2001). The identification of HLA class I and II ligands, B-cell and T-cell epitopes is crucial to design epitope-based vaccine (Petrovsky and Brusic 2002). To predict the T-cell epitope is required the identification of proteasomal peptide cleavage sites, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binding peptides, and transporters associated with antigen presentation (TAP) molecules. These identifications are achieved by computational approaches using several tools and servers (Brusic et al. 2004; Peters et al. 2003; Bhasin and Raghava 2004; Nielsen et al. 2005). B-cell epitope identification is helpful to predict more potential peptide vaccine candidate. Further, allergenicity assessment is required to avert any harm for human health. We have used these in silico approach on LASV to design a synthetic peptide vaccine candidate. For the post therapy against LASV we have also tried to identify the binding and active site by predicting 3D model. So, this study also could pave the lead to design drug candidates on glycoprotein for the treatment against LASV.

Materials and methods

Retrieving protein sequences

Available all the protein sequences of LASV were retrieved in FASTA format from UniProtKB (http://www.uniprot.org) for this study.

Prediction of the most potent antigenic protein

Each of the retrieved FASTA sequence of corresponding protein was submitted in VaxiJen v2.0 (Doytchinova and Flower 2007) in plain format to identify the antigenic score. The protein with highest antigenic score was not taken for further analysis because polymerase protein could not be ideal for vaccine design as it is needed for DNA synthesize. In this case, glycoprotein (UniprotKBID: D6NLU3) could be ideal candidate for vaccine design as it is a surface protein.

Prediction of T-cell epitope

NetCTL 1.2 server which is based on neural network architecture was utilized to predict the Cytotoxic (CD8+) T-cell epitopes for each of the 12 HLA class I super types (A1, A2, A3, A24, A26, B7, B8, B27, B39, B44, B58, B62) (Larsen et al. 2007; Lund et al. 2004). The selected FASTA sequence of the glycoprotein was submitted to this server at 0.5 threshold level to have sensitivity and specificity of 0.89 and 0.94, respectively which allowed to find out more epitopes. An integrated value of transporter of antigenic peptide (TAP) transport efficiency, MHC-I binding and proteasomal cleavage efficiency values were also measured by this web-based tool.

Immune epitope database (IEDB) was utilized to predict the MHC-1 binding with the selected epitope by the measurement of IC50 values (Buus et al. 2003). The alleles having binding affinity IC50 less than 200 nm were chosen for selected 5 epitopes for further analysis.

Proteasomal cleavage/TAP transport/MHC class I combined predictor (Lundegaard et al. 2006) was used to find proteasomal cleavage score, TAP score, processing score and MHC-I binding score which are essential for the suitable T-cell epitope.

MHC class II epitope prediction

The most probable MHC class I T-cell epitope was studied to know whether it can generate MHC class II immune response. For this reason, MHC-II binding prediction tools were used from immune epitope database (IEDB) (Wang et al. 2010). HLA-DP, HLA-DQ and HLA-DR alleles of human were separately estimated.

Epitope conservancy analysis

To analyze the conservancy of each peptide of selected 5 epitopes, the web-based tool from IEDB (Bui et al. 2007) analysis resource was performed. Conservancy of each epitope was estimated for both filtered proteins and all of the glycoprotein of LASV found in UniProtKB.

Population coverage prediction

Predicted 5 epitopes with corresponding different HLA Class I and II alleles were submitted to the population coverage analysis tool of IEDB (http://tools.immuneepitope.org/tools/population/iedb input) with the default parameters like “Query by: Area, Country and Ethnicity” to find out the human population coverage for each epitope.

Design of the three-dimensional (3D) epitope structure

The conserved T-cell epitope peptide sequence SSNLYKGVY was employed in PEP-FOLD (Thevenet et al. 2012) server to build the 3D structure that was further utilized to analyze the interactions with HLA (I and II).

Docking simulation study

Before performing the docking simulation study the 3D crystal structure of HLA-B*15:01 (PDB ID:1XR8) and HLA-DR (PDB ID:1D5 M) from HLA-II were retrieved from RCSB (Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics) (Berman et al. 2000) and then prepared for docking runs by removing the ligands from these structure. Thereafter, Autodock Vina (Trott and Olson 2010) was used for the assurance of the binding between HLA (I and II) molecules predicted epitope, SSNLYKGVY.

Prediction of B-cell epitope

The portion of the antigen that interacts with B-lymphocytes is the B-cell epitope. It is required to know whether the potential epitope is able to generate humoral immune response interacting with B lymphocyte as it is the only target to predict B-cell epitope (Nair et al. 2002). B-cell antigenicity was identified using different tools available in IEDB. These tools are Kolaskar and Tongaonkar antigenicity scale (Kolaskar and Tongaonkar 1990), Emini surface accessibility prediction (Emini et al. 1985), Karplus and Schulz flexibility prediction (Karplus and Schulz 1985) and Bepipred linear epitope prediction analysis (Larsen et al. 2006a, b). The antibodies can recognize beta turn of the protein (Rini et al. 1992). Such kind of property makes the beta turn of the protein as an antigenic. The beta turn was predicted using the Chou and Fasman beta-turn prediction tool (Chou and Fasman 1978).

Allergenicity assessment

AllerHunter was utilized to predict the sequence-based allergenicity of the epitopes (Liao and Noble 2010; Muh et al. 2009) which is constructed on a combination with support vector machine (SVM).

Structural analysis of most potent antigenic protein

The three-dimensional (3D) structure of glycoprotein of LASV was constructed using protein modeling software MODELLER 9v11 (Šali et al. 1995) through HHpred (Söding et al. 2005; Söding 2005). Energy minimization of the 3D built model was performed by the utilization of YASARA (Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application) (Krieger et al. 2009; Sippl 1993; Sander and Vriend 1993; Kuszewski and Clore 1997) server to refine the any gaps and structural alignment of the 3D structure. The predicted 3D model of glycoprotein was evaluated by ProCheck tools (Laskowski et al. 1993) and Anolea (Melo et al. 1997).

Binding site study

We used the Meta pocket server 2.0 (Bingding 2009) and Discovery studio (Van Joolingen et al. 2005) for analyzing binding site and facilitating the drug binding to our projected model. By these servers, the predicted binding site of our created model could be employed for the detection of effective drugs against glycoprotein.

Active site study

Active site analysis was performed to enrich a considerable insight of the docking simulation study. Computed Atlas of Surface Topography of proteins (CASTp) (Dundas et al. 2006) was used to explore the active amino acid residues of the built model. Therefore, the binding sites, active sites, internal cavities of proteins, structural pockets, area, shape and volume of every pocket were identified and determined.

Results

Retrieving protein sequences

A total of 1046 protein sequences, all the available proteins of various LASV strains in UniProtKB after filtering, including 225 glycoproteins, 2 polymerase RDRP, 28 RNA-directed RNA polymerase L, 6 envelope glycoprotein, 298 polymerase, 1 glycoprotein C, 1 putative glycoprotein, 2 nucleocapsid protein, 312 nucleoprotein, 24 pre-glycoprotein polyprotein GP complex, 3 ring finger protein, 144 Z protein were retrieved from UniProtKB database Supplementary table, S1.

Prediction of the most potent antigenic protein

VaxiJen v2.0 server revealed the highest surface antigenic protein UniprotKB id: D6NLU3 which is glycoprotein with a total prediction score of 0.6739 Supplementary table, S1. Herein, D6NLU3 has been selected over the other polymerase and Z protein because they could not be ideal for vaccine design as they are not the surface protein.

Prediction of T-cell epitope

The best 5 epitopes were selected based on combinatorial score from NetCTL prediction server (Table 1).

Table 1.

The selected epitopes based on their overall score predicted by the NetCTL server

| Number | Epitopes | Overall score (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SSNLYKGVY | 2.9170 |

| 2 | CTKNNSHHY | 2.9140 |

| 3 | MTMPLSCTK | 1.3934 |

| 4 | NLYKGVYEL | 1.2724 |

| 5 | VQYNLSHSY | 1.0182 |

The MHC-I alleles for which the epitopes showed higher affinity (IC50 < 200 nM) were selected for further analysis from IEDB database (Table 2). There is an inverse relationship between binding affinity of the epitopes with the MHC-I alleles and IC50 values.

Table 2.

The five potential T-cell epitopes, along with their interacting MHC-I alleles and total processing score, and epitope conservancy result

| Epitope | Interacting MHC-I allele with an affinity of < 200 nM (the total score of Proteasome score, TAP score, MHC-I score and processing score) | Epitope conservancy within whole proteins (%) | Epitope conservancy within glycoproteins (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSNLYKGVY | HLA-A*01:01 (0.29) HLA-C*06:02 (0.3) HLA-C*15:02 (0.55) HLA-B*35:01 (0.59) HLA-A*32:15 (0.6) HLA-C*07:01 (0.61) HLA-B*15:01 (0.64) HLA-B*40:13 (0.65) HLA-C*03:03 (0.8) HLA-C*14:02 (0.88) HLA-A*68:23 (0.98) HLA-B*15:03 (1.03) HLA-A*32:07 (1.04) HLA-B*15:02 (1.09) HLA-C*12:03 (1.41) HLA-B*15:17 (1.51) HLA-B*27:20 (1.75) |

23.90 | 98.21 |

| CTKNNSHHY | HLA-C*14:02 (0.32) HLA-C*03:03 (0.38) HLA-A*68:23 (0.59) HLA-B*27:05 (0.65) HLA-C*12:03 (1.08) HLA-A*32:07 (1.22) HLA-B*27:20 (2.06) |

24.19 | 99.55 |

| MTMPLSCTK | HLA-B*40:13 (− 0.35) HLA-B*15:02 (− 0.28) HLA-C*12:03 (− 0.26) HLA-B*39:01 (− 0.26) HLA-C*07:01 (− 0.18) HLA-A*02:17 (− 0.14) HLA-C*07:02 (− 0.06) HLA-C*14:02 (− 0.04) HLA-A*68:23 (− 0.02) HLA-A*32:07 (0.01) HLA-C*03:03 (0.13) HLA-B*27:20 (0.85) |

20.27 | 81.25 |

| NLYKGVYEL | HLA-C*03:03 (− 0.04) HLA-A*32:15 (0.16) HLA-B*15:03 (0.21) HLA-C*14:02 (0.28) HLA-C*07:02 (0.29) HLA-C*12:03 (0.37) HLA-A*68:23 (0.43) HLA-B*40:13 (0.67) HLA-A*32:07 (0.88) HLA-A*02:50 (0.89) HLA-A*24:03 (1.09) HLA-B*27:20 (1.44) |

19.22 | 81.25 |

| VQYNLSHSY | HLA-C*05:01 (− 1.17) HLA-A*32:15 (− 1.12) HLA-B*40:13 (− 0.89) HLA-A*68:23 (− 0.83) HLA-A*11:01 (− 0.81) HLA-C*12:03 (− 0.38) HLA-A*32:07 (− 0.19) HLA-B*27:20 (0.72) |

8.41 | 33.93 |

The proteasome complex is responsible for cleavage of peptide bonds of proteins to convert them into peptides. These peptides are transported to endoplasmic reticulum TAP (transporter of antigenic peptides) where they bind to MHC-I molecules. These peptide-MHC molecules are then transported to the cell membrane where they are presented to cytotoxic T cell. In this case, the overall score was taken as the higher the overall score meant the higher the efficiency of all these processes. The predicted overall score in represented shortly in Table 2.

Among the 5 T-cell epitopes, a 9-mer epitope, SSNLYKGVY, position: 41–49 was found to interact with the most MHC-I alleles including HLA-B*27:20, HLA-B*15:17, HLA-C*12:03, HLA-B*15:02, HLA-A*32:07, HLA-B*15:03, HLA-A*68:23, HLA-C*14:02, HLA-C*03:03, HLA-B*40:13, HLA-B*15:01, HLA-C*07:01, HLA-A*32:15, HLA-B*35:01, HLA-C*15:02, HLA-C*06:02, HLA-A*01:01. Besides, SSNLYKGVY was found to interact with the most MHC-II alleles including HLA-DQA1*05:01/DQB1*03:01, HLA-DQA1*05:01/DQB1*02:01,HLA-DQA1*01:02/DQB1*06:02,HLA-DQA1*03:01/DQB1*03:02, HLA-DQA1*01:01/DQB1*05:01, HLA-DRB1*01:01, HLA-DRB1*04:01, HLA-DRB4*01:01, HLA-DRB1*09:01, HLA-DRB3*01:01, HLA-DRB1*07:01, HLA-DRB5*01:01, HLA-DRB1*13:02, HLA-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DRB1*04:05, HLA-DRB1*11:01 (Tables 2, 3). But, the predicted epitope did not interact with HLA-DP allele (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

MHC-II molecules from the desired peptide epitope

| Epitope peptide | MHC-II molecules |

|---|---|

| SSNLYKGVY | HLA-DQA1*05:01/DQB1*03:01 |

| HLA-DQA1*05:01/DQB1*02:01 | |

| HLA-DQA1*01:02/DQB1*06:02 | |

| HLA-DQA1*03:01/DQB1*03:02 | |

| HLA-DQA1*01:01/DQB1*05:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*01:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*04:01 | |

| HLA-DRB4*01:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*09:01 | |

| HLA-DRB3*01:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*07:01 | |

| HLA-DRB5*01:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*13:02 | |

| HLA-DRB1*03:01 | |

| HLA-DRB1*04:05 | |

| HLA-DRB1*11:01 |

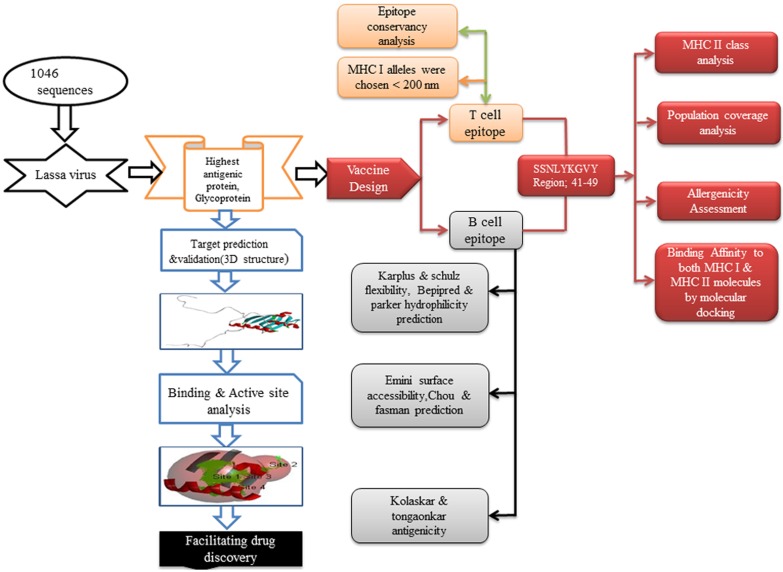

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the whole work

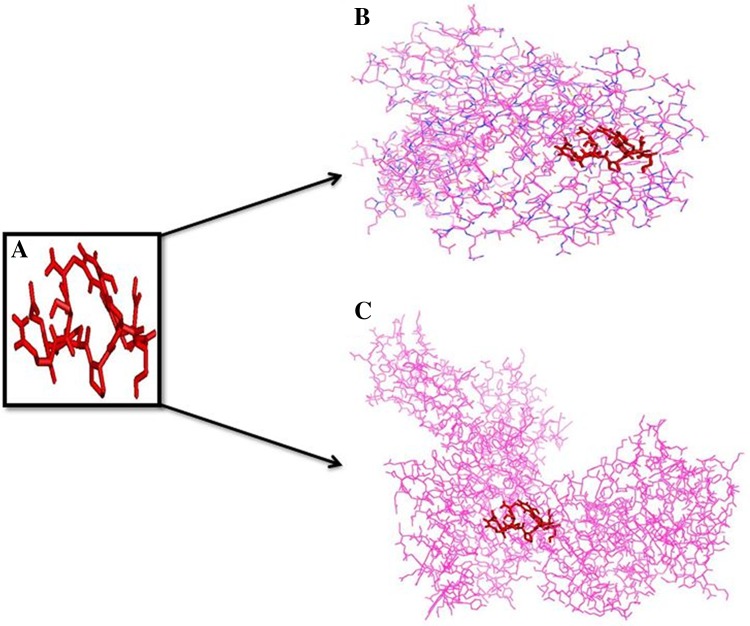

PEP-FOLD 2.0 server predicted a 3D structure of our suggested SSNLYKGVY epitope shown in Fig. 2a. Then AutoDock Vina generated the binding energy for the epitope SSNLYKGVY with HLA-I and HLA-II molecules. The interacted binding energy with HLA-B*1501 (HLA-I) was − 7.2 while the HLA-DR (HLA-II) generated − 6.99 kcal/mol. The 3D structures with epitope are shown in Fig. 2b, c.

Fig. 2.

Binding confirmation of predicted epitope to both MHC-I and MHC-II. a Epitope structure. b Binding affinity of epitope structure to HLA-I molecule. c Binding affinity of epitope structure to HLA-II molecule

Using the IEDB conservancy analysis tool we estimated conservancy of the selected 5 epitopes. SSNLYKGVY showed the second highest conservancy within both all of the available proteins and only glycoproteins of LASV (Table 2).

Population coverage of 5 epitopes with their corresponding MHC-I alleles for different continent and countries are shown in Table 4. Among the continents, Europe showed the highest population coverage of 91.20% as well as South Africa showed the second highest population coverage of 89.83%.

Table 4.

Population coverage by epitopes with corresponding Class I HLA alleles for different areas

| Population/area | Coverage (%) | Average hit | PC90 |

|---|---|---|---|

| South Asia | 80.45 | 2.25 | 0.51 |

| Southeast Asia | 79.77 | 2.23 | 0.49 |

| Southwest Asia | 74.87 | 1.88 | 0.40 |

| Europe | 91.20 | 3.14 | 1.08 |

| England | 89.66 | 2.73 | 0.97 |

| Finland | 93.70 | 3.44 | 1.31 |

| Germany | 93.66 | 3.28 | 1.28 |

| Ireland Northern | 95.89 | 3.22 | 1.51 |

| Ireland South | 96.82 | 3.39 | 1.67 |

| East Africa | 69.43 | 1.56 | 0.33 |

| Kenya | 75.88 | 1.70 | 0.41 |

| West Africa | 68.17 | 1.51 | 0.31 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 49.15 | 0.77 | 0.20 |

| North Africa | 80.56 | 2.21 | 0.51 |

| Mali | 61.99 | 1.51 | 0.26 |

| Morocco | 87.63 | 2.16 | 0.81 |

| South Africa | 89.83 | 2.63 | 0.98 |

| North America | 81.64 | 2.34 | 0.54 |

| United States | 81.87 | 2.36 | 0.55 |

| South America | 67.97 | 1.77 | 0.31 |

AllerHunter calculated the sequence-based allergenicity of the predicted epitopes. However, the query epitopes were predicted as non-allergen which was 0.00 (sensitivity = 93.0%, specificity = 79.4%).

Prediction of B-cell epitope

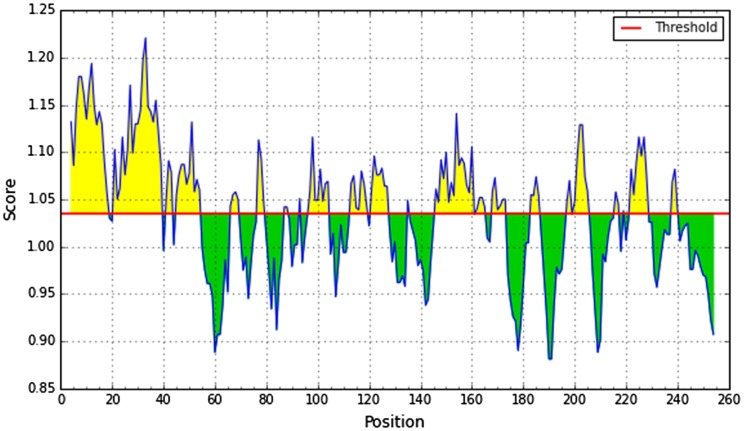

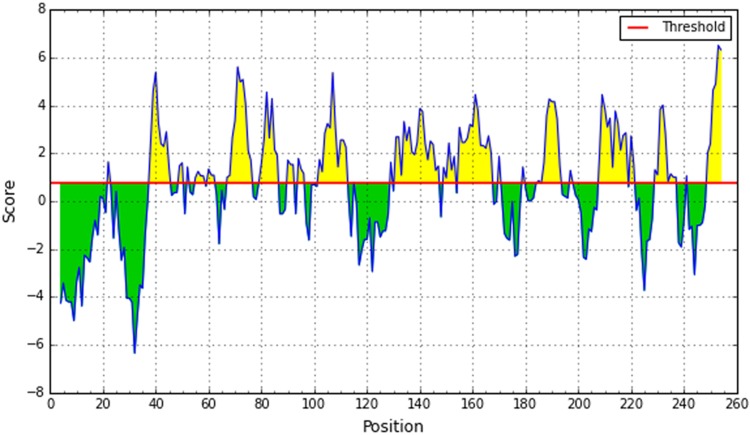

We used different analysis methods for the prediction of B-cell epitope. The physico-chemical properties of peptides were determined by utilizing the Kolaskar and Tongaonkar antigenicity prediction method. The average antigenic propensity of the protein was 1.030. The values greater than 1.00 were considered as potential antigenic determinant. Six epitopes were considered to have the potentiality for produce the B-cell immunity. The results are summarized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Kolashkar and Tongaonkar antigenicity prediction. Here the x-axis represents sequence position and y-axis represents antigenic propensity. The threshold value is 1.00. The regions above the threshold, shown in yellow, are antigenic

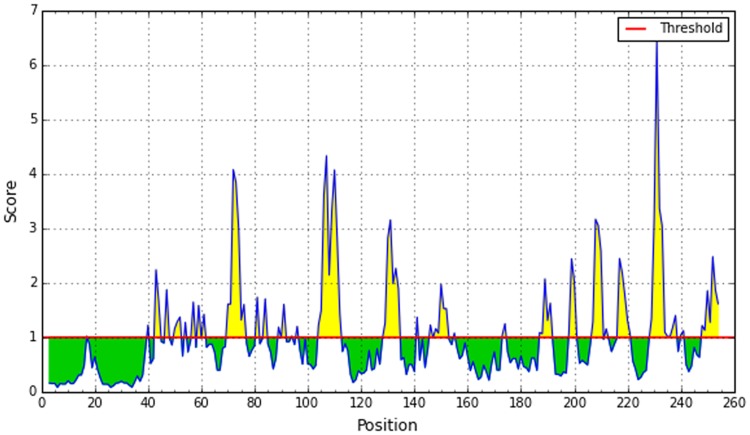

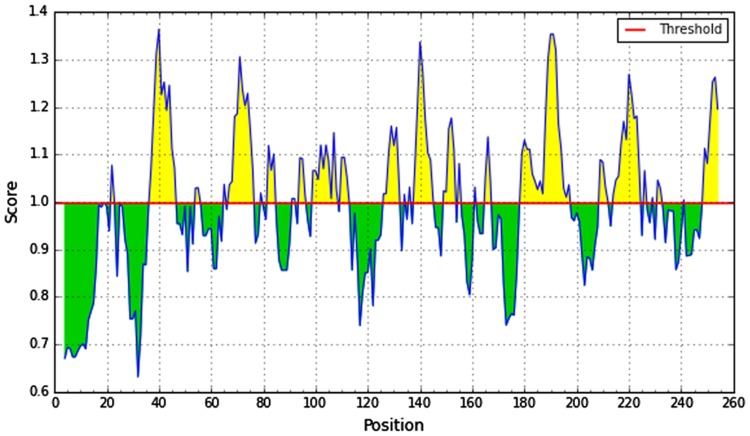

A potent B-cell epitope must have surface accessibility and the hydrophilic regions. Emini surface accessibility prediction showed the highest and the lowest result of 4.019 and 0.063, respectively (Fig. 4), and Parker hydrophilicity prediction showed the highest and lowest value of 6.8 and − 7.629, respectively (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Emini surface accessibility prediction of the most antigenic protein. The x-axis and y-axis represent the sequence position and surface probability, respectively. The threshold value is 1.0. The regions above the threshold, shown in yellow, are antigenic

Fig. 5.

Parker hydrophilicity scale. Here the x-axis and y-axis represent sequence position and hydrophilicity scale, respectively. The threshold is 1.0. The regions above the threshold are hydrophilic, shown in yellow

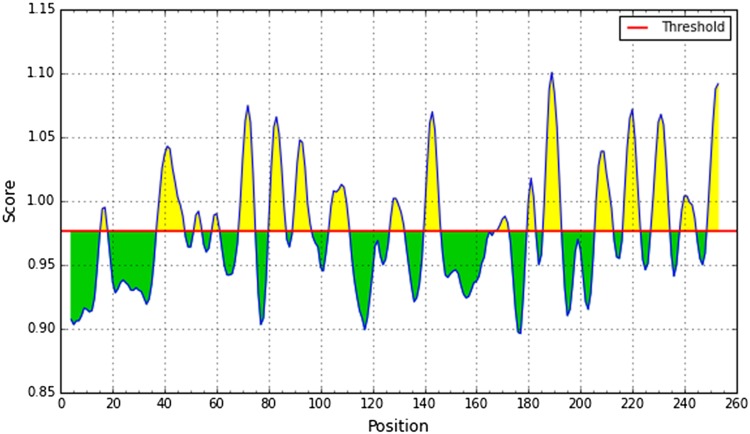

In the beta sheet region, the beta turns are frequently accessible and significantly hydrophilic in nature. These are two properties of antigenic regions of a protein (Rose et al. 1985). Therefore, Chou and Fasman beta-turn prediction was taken place to predict these properties. As the region 42–55 represents the highest score, it was considered as beta turn region (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Chou and Fasman beta-turn prediction. The x-axis and y-axis represent position and score, respectively. The threshold is 1.0. The regions having beta turns are shown in yellow

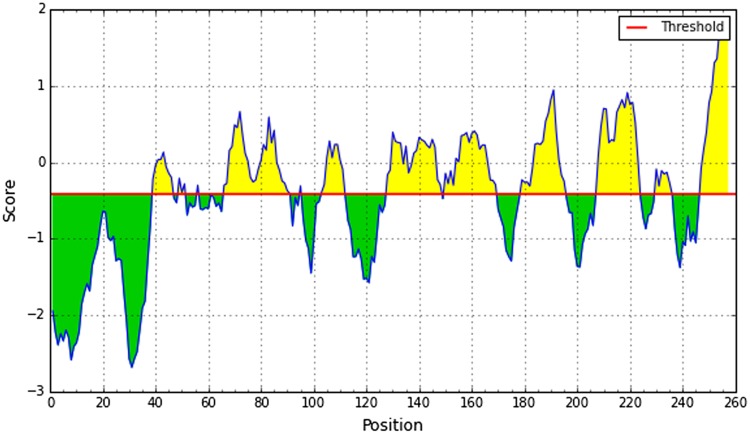

It is experimentally proved that the flexibility of the peptide is correlated with antigenicity (Novotný et al. 1986). Herein Karplus and Schulz method predicted the flexibility of epitope region. According to the results, 42–50 region showed higher flexibility (Fig. 7). To predict linear B-cell epitope, the Bepipred linear epitope prediction tool was used. Region 44–59 showed the highest value for this purpose (Fig. 8). After cross-referencing all the data, we confirmed that peptide sequence from 41 to 49 amino acids, SSNLYKGVY, claimed the highest potential to induce B-cell immune response.

Fig. 7.

Karplus and Schulz flexibility prediction. Here, x-axis and y-axis represent position and score, respectively. The threshold is 1.00. The flexible regions are shown in yellow

Fig. 8.

Bepipred linear epitope prediction. The x-axis and y-axis represent the position and score, respectively. The threshold is 0.35. The higher peak regions, shown in yellow, indicate more potent B

3D model quality assessment

A 3D model of the glycoprotein was constructed to utilize a template 3bso_A using MODELLER (Fig. 9a). Then, the model refinement was done by YASARA server that produces the START energy − 58561.6 kj/mol to END energy − 118522.2 kj/mol for the built model Supplementary Fig S1. The amino acids favored and disfavored region with φ and ψ distribution value of the Ramachandran plot through PROCHEK of non-glycine and non-proline residues were shown in Supplementary Fig S2 and Supplementary Table 1. Further, anolea quality assessment also ensured the alignment of majority amino acid residues in good region. Supplementary Fig S3.

Fig. 9.

3D structure of glycoprotein (a). Binding site of glycoprotein (b)

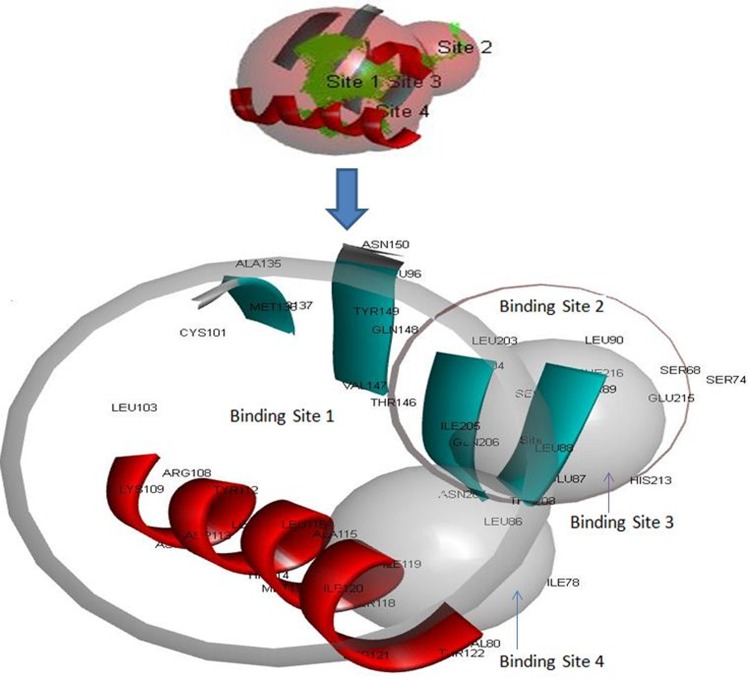

Binding site and active site analysis of built model

Meta pocket tools explored the two binding sites for the binding of molecules or ligands to its target glycoprotein (Figs. 9b, 10 and Table 5). CASTp server conferred an important prediction about the interaction sites on protein with ligand molecules (Fig. 10 and Table 5).

Fig. 10.

Binding site analysis of glycoprotein. Here, four binding site and their amino acid residues were shown

Table 5.

Binding site and residues analysis

| Properties | Binding site 1 | Binding site 2 | Binding site 3 | Binding site 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid size (X, Y, Z) | X = − 2.651, Y = 16.81, Z = − 4.173 | X = − 13.901, Y = 19.931, Z = − 9.173 | X = − 3.901, Y = 18.931, Z = − 16.923 | X = − 2.151, Y = 22.431, Z = − 7.423 |

| Grid space | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Grid angles | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Volume | 230.375 | 18.875 | 14.5 | 13.125 |

| Residues involved in binding site | Met36, Ile78, Leu86, Leu88, Leu111, Asp113, Met117, Ser118, Ile120, Phe123, Leu125, Val147, Ile166, Val170, Ile205, Gln206, | Ser74, Leu88, Thr89, Leu90, Ala167, Leu181, Tyr183, Leu203 | Glu87, Thr89, Thr208, His213, Glu215, Phe216, Ser217 | Ile78, Val80, Leu86, Leu88, Ala115, Ser118, Ile119 |

| Active residues in binding site | Ile78, Leu86, Asp113, Ser118, Phe123, Val147, Ile205, Gln206 | Ser74, Thr89, Leu90, Ala167, Leu203 | Glu87, Thr89, Glu215, Phe216, Ser217 | Ile78, Leu86, Ala115, Ser118, Ile119 |

Discussion

The outline of the whole study is illustrated in Fig. 1. To recognize and characterize the potential epitopes from antigenic protein of LASV, several bioinformatics tools are being used that may produce efficient B-cell and T-cell mediated immunity.

The glycoprotein sequence UniprotKB id: D6NLU3 of LASV was considered as potent having a well conserved T-cell epitope Supplementary table, S1. Here, from this sequence NETCTL server predicted 5 epitopes based on their overall score from which epitope SSNLYKGVY posed the highest score 2.9170 (Table 1). The most conserved T-cell epitope amongst 5 epitopes from NetCTL server was SSNLYKGVY that showed higher conservancy, 98.21% (Table 2). In our study, we found that 17 HLA-I (HLA-A, HLA-B and HLA-C) alleles could interact with SSNLYKGVY (Table 2). Besides, there are 16 HLA-II molecules could also interact with the epitope SSNLYKGVY (Table 3). The efficiency of an epitope vaccine to a great extent relies on the exact interaction between epitope and HLA alleles, expected from this high specific binding affinity. The affinity exposing HLA alleles by SSNLYKGVY were looked for population coverage. LASV endemic regions were the main focus of search. South Africa, a LASV endemic zone was recorded (89.83%) the highest population coverage (Table 4).

In Europe, the coverage was 91.20% and North America also had a considerable percentage as the most recent LASV outbreak. The epitope declared as non-allergen to be an ideal candidate vaccine. The results urged that the vaccine might be efficient for a wide epidemic zone all over the world. To ensure the binding affinity the epitope was docked to both HLA-I allele (HLA-B*15:01) and HLA-II (HLA-DR) which resulted − 7.2 and − 6.99 kcal/mol. According to these results, it is therefore to be confirmed that the epitope could bind effectively to HLA-I and HLA-II (Fig. 2).

The epitopes affinity for MHC-I molecules and support its location as a new vaccine candidate was confirmed by this in silico analysis. The B-cell epitope which could induce primary and secondary immunity together were searched for LASV glycoprotein. We performed bioinformatics tools from IEDB database to predict B-cell epitopes based on the important features by protein analysis. The common features of the region were mentioned such as beta turns, accessibility to surface, hydrophilic comparatively than other regions and proved to be antigenic (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and Table 5). The region from 41 to 49 was predicted as potent B-cell epitope using Bepipred tool and all the data were referenced (Fig. 8). The 9-mer epitope SSNLYKGVY was the most satisfactory peptide as B-cell epitope.

When LASV infection rises to chronic stage it can last for long times. Therefore, therapeutic agent is necessary to minimize or eliminate the chronic symptoms completely caused by the viral infection. Moreover, to provide an inclusive safety against LASV infection number of universal drugs is required. In our study, we predicted the glycoprotein 3D structure (Fig. 9a) for revealing of binding site and active site so that this study could effectively contribute to design more drugs against Lassa virus. Therefore, we have projected a refined 3D model Supplementary Fig, S1 which showed 94% amino acids were aligned in favored region Supplementary Fig, S2 and Supplementary Table 2 further model validation confirmed us to be good quality model for the studies in drug discovery field Supplementary Fig, S3. Consequently, we have identified four binding sites Fig. 9b and these active sites where the drugs could bind. There were 16 amino acid residues Met36, Ile78, Leu86, Leu88, Leu111, Asp113, Met117, Ser118, Ile120, Phe123, Leu125, Val147, Ile166, Val170, Ile205, Gln206 involved in binding site 1 (comprised with X = − 2.651, Y = 16.81, Z = − 4.173; grid space 0.5 and grid angles X, Y, Z = 90) in which 8 amino acid residues Ile78, Leu86, Asp113, Ser118, Phe123, Val147, Ile205, Gln206 found as active residues. On the other hand, 8 amino acid residues Ser74, Leu88, Thr89, Leu90, Ala167, Leu181, Tyr183, Leu203 were involved in binding site 2 (comprised with Grid size X = −13.901, Y = 19.931, Z = − 9.173; Grid space 0.5 and Grid angles X, Y, Z = 90) where 5 amino acid residues Ser74, Thr89, Leu90, Ala167, Leu203 were predicted as active residues. In binding site 3 (comprised with Grid size X = − 3.901, Y = 18.931, Z = − 16.923; Grid space 0.5 and Grid angles X, Y, Z = 90), Glu87, Thr89, Thr208, His213, Glu215, Phe216, Ser217 were found, whereas Glu87, Thr89, Glu215, Phe216, Ser217 anticipated as active residues. Lastly, Ile78, Val80, Leu86, Leu88, Ala115, Ser118, Ile119 were found in binding site 4 (comprised with Grid size X = − 2.151, Y = 22.431, Z = − 7.423; Grid space 0.5 and Grid angles X, Y, Z = 90) where Ile78, Leu86, Ala115, Ser118, Ile119 found as active residues (Fig. 10 and Table 5).

In this research, we have suggested a potent T-cell and B-cell epitope which might successfully be used to induce a complete immune response against LASV. Furthermore, the revealing of binding and active site of glycoprotein could play a myriad role for expediting the drug discovery field to design number of effective drugs against LASV.

Conclusion

In our study, the immunoinformatics analysis of glycoprotein proposed a peptide SSNLYKGVY that would let to be a candidate target for the universal vaccine to trigger both T-cell and B-cell immune response. And also with binding and target site depiction on its predicted 3D model could assist to drug design against LASV. However, all of these results generated from in silico analysis might explore a new strategy for better medication against LASV.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author reports no acknowledgments of this work.

Authors contribution

MUH and KMKK: Conceived, designed, and guided the study, analyzed the data, performed bioinformatics analysis, helped in drafting and performed critical revision. TMO and MUH: Helped to design the study, performed bioinformatics analysis, drafted and developed the manuscript and performed critical revision. ARO and MM: Guided the study, acquisition and analysed the data, helped in drafting the manuscript and performed critical revision. AZS, SRA and MMI: Helped in bioinformatics analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors have approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors report no competing interest in this work.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-018-1106-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Mohammad Uzzal Hossain, Phone: +88-02-7788443, Email: uzzalbge10044@gmail.com, Email: uzzal@nib.gov.bd, http://www.nib.gov.bd.

Taimur Md. Omar, Email: taimurmd.omar@gmail.com

Arafat Rahman Oany, Email: arafatr@outlook.com.

K. M. Kaderi Kibria, Phone: +88-0921-62407, Email: km_kibria@yahoo.com.

Abu Zaffar Shibly, Email: zaffarshibly1987@gmail.com.

Md. Moniruzzaman, Email: monirbge06033@gmail.com

Syed Raju Ali, Email: m15121307@bau.edu.bd.

Md. Monirul Islam, Email: moniruli160@gmail.com.

References

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, et al. The protein data bank. Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28(1):235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin M, Raghava GP. Analysis and prediction of affinity of TAP binding peptides using cascade SVM. Protein Sci. 2004;13(5):596–607. doi: 10.1110/ps.03373104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingding H. MetaPocket: a meta approach to improve protein ligand binding site prediction. OMICS. 2009;13(4):325–330. doi: 10.1089/omi.2009.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdette DN, Edmonds E, Smith C, et al. A highly immunogenic trivalent T cell receptor peptide vaccine for multiple sclerosis. Multip Scler J. 2005;11(5):552–561. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1225oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusic V, Bajic VB, Petrovsky N. Computational methods for prediction of T-cell epitopes—a framework for modelling, testing, and applications. Methods. 2004;34(4):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui HH, Sidney J, Li W, Fusseder N, Sette A. Development of an epitope conservancy analysis tool to facilitate the design of epitope-based diagnostics and vaccines. BMC Bioinf. 2007;8(1):361. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buus S, Lauemøller SL, Worning P, et al. Sensitive quantitative predictions of peptide-MHC binding by a ‘Query by Committee’ artificial neural network approach. Tissue Antigens. 2003;62(5):378–384. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerdino-tarraga AM, et al. The complete genome sequence and analysis of Corynebacterium diphtheriae NCTC13129. Nucl Acids Res. 2003;31:6516. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrel RN, de Lamballerie X. Arenaviruses other than Lassa virus. Antiviral Res. 2003;57:89–100. doi: 10.1016/S0166-3542(02)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou PY, Fasman GD. Empirical predictions of protein conformation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1978;47:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.47.070178.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doytchinova IA, Flower DR. VaxiJen: a server for prediction of protective antigens, tumour antigens and subunit vaccines. BMC Bioinf. 2007;8:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dundas J, Ouyang Z, Tseng J, Binkowski A, Turpaz Y, et al. CASTp, computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucl Acids Res. 2006;34:116–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emini EA, Hughes JV, Perlow DS, Boger J. Induction of hepatitis A virus-neutralizing antibody by a virus-specific synthetic peptide. J Virol. 1985;55(3):836–839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.836-839.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichet-Calvet E, Rogers DJ. Risk maps of Lassa fever in West Africa. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(3):e388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain RN. MHC-dependent antigen processing and peptide presentation: providing ligands for T lymphocyte activation. Cell. 1994;76:287. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther S, Emmerich P, Laue T, Kuhle O, Asper M, Jung A, et al. Imported lassa fever in Germany: molecular characterization of a new lassa virus strain. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6(5):466–476. doi: 10.3201/eid0605.000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther S, Weisner B, Roth A, Grewing T, Asper M, Drosten C. Lassa fever encephalopathy: Lassa virus in cerebrospinal fluid but not in serum. J Infect Dis. 2001;184(3):345–349. doi: 10.1086/322033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas WH, Breuer T, Pfaff G, Schmitz H, Kohler P, Asper M, et al. Imported Lassa fever in Germany: surveillance and management of contact persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(10):1254–1258. doi: 10.1086/374853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer J, Gallazzi F, Bono E, et al. Peptide binding specificity of HLA-DR4 molecules: correlation with rheumatoid arthritis association. J Exp Med. 1995;181(5):1847–1855. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.5.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan MA, Khan MA, Datta A, Mazumder MHH, Hossain MU. A comprehensive immunoinformatics and target site study revealed the corner-stone towards Chikungunya virus treatment. Mol Immunol. 2015;65(1):189–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Joolingen WR, Jong TD, Lazonder AW, Savelsbergh ER, Manlove S. Co-Lab: research and development of an online learning environment for collaborative scientific discovery learning. Comput Hum Behav. 2005;21(4):671–688. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2004.10.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karplus PA, Schulz GE. Prediction of chain flexibility in proteins. Naturwissenschaften. 1985;72(4):212–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01195768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SH, Goba A, Chu M. New opportunities for field research on the pathogenesis and treatment of Lassa fever. Antivir Res. 2008;78:103–115. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Schiffman K, Disis ML. Immunization with a HER-2/neu helper peptide vaccine generates HER-2/neu CD8 T-cell immunity in cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(4):477–484. doi: 10.1172/JCI11752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolaskar AS, Tongaonkar PC. A semi-empirical method for prediction of antigenic determinants on protein antigens. FEBS Lett. 1990;276(1–2):172–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80535-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, Tyka M, Baker D, Karplus K. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77:114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhns JJ, Batalia MA, Yan S, Collins EJ. Poor binding of a HER-2/neu epitope (GP2) to HLA-A2.1 is due to a lack of interactions with the center of the peptide. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(51):36422–36427. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuszewski J, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Improvements and extensions in the conformational database potential for the refinement of NMR and X-ray structures of proteins and nucleic acids. J Magn Reson. 1997;125:171–177. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JE, et al. Improved method for predicting linear B-cell epitopes. Immunome Res. 2006;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen JE, Lund O, Nielsen M. Improved method for predicting linear B-cell epitopes. Immunome Res. 2006;2(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1745-7580-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen MV, Lundegaard C, Lamberth K, Buus S, Lund O, Nielsen M. Large-scale validation of methods for cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope prediction. BMC Bioinf. 2007;8:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lassa fever, imported case, Netherlands (2000) Releveepidemiologiquehebdomadaire/Section d’hygiene du Secretariat de la Societe des Nations=Weekly epidemiological record/Health Section of the Secretariat of the League of Nations 75(33):265

- Lassa fever imported to England (2000) Commun Dis Rep CDR Week 10(11):99 [PubMed]

- Liao L, Noble WS. Combining pairwise sequence similarity and support vector machines for detecting remote protein evolutionary and structural relationships. J Comput Biol. 2010;10(6):857–868. doi: 10.1089/106652703322756113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JA, Weilenman C, Audran R, et al. Synthetic malaria vaccine elicits a potent CD8(+) and CD4(+) T lymphocyte immune response in humans. Implications for vaccination strategies. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31(7):1989–1998. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<1989::AID-IMMU1989>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loureiro ME, Wilda M, Levingston-Macleod JM. Molecular determinants of Arenavirus Z protein homo-oligomerization and L polymerase binding. J. Virol. 2011;85(23):05691–05611. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05691-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund O, Nielsen M, Kesmir C, Petersen AG, Lundegaard C, et al. Definition of supertypes for HLA molecules using clustering of specificity matrices. Immunogenetics. 2004;55:797–810. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0647-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundegaard C, Nielsen M, Lund O. The validity of predicted T-cell epitopes. Trends Biotechnol. 2006;24(12):537–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JB, Fisher HSP. Lassa fever. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;262:75–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo F, Devos D, Depiereux E, Feytmans E. ANOLEA: a www server to assess protein structures. ISMB. 1997;5:187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muh HC, Tong JC, Tammi MT. AllerHunter: a SVM-pairwise system for assessment of allergenicity and allergic cross-reactivity in proteins. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair DT, Singh K, Siddiqui Z, Nayak BP, Rao KV, Salunke DM. Epitope recognition by diverse antibodies suggests conformational convergence in an antibody response. J Immunol. 2002;168(5):2371–2382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Lund O, Kesmir C. The role of the proteasome in generating cytotoxic T-cell epitopes: insights obtained from improved predictions of proteasomalcleavage. Immunogenetics. 2005;57(1–2):33–41. doi: 10.1007/s00251-005-0781-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotný J, Handschumacher M, Haber E, et al. Antigenic determinants in proteins coincide with surface regions accessible to large probes (antibody domains) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(2):226–230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.2.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters B, Bulik S, Tampe R, et al. Identifying MHC class I epitopes by predicting the TAP transport efficiency of epitope precursors. J Immunol. 2003;171(4):1741–1749. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.4.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovsky N, Brusic V. Computational immunology: the coming of age. Immunol Cell Biol. 2002;80(3):248–254. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2002.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richmond JK, Baglole D. Lassa fever: epidemiology, clinical features, and social consequences. BMJ. 2003;327:1271–1275. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7426.1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rini JM, Schulze-Gahmen U, Wilson IA. Structural evidence for induced fit as a mechanism for antibody-antigen recognition. Science. 1992;255(5047):959–965. doi: 10.1126/science.1546293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GD, Gierasch L, Smith JA. Turns in peptides and proteins. Adv Protein Chem. 1985;37:1–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safronetz D, Job E, Nafomon S, Traore SF, Raffel SJ, Fischer ER, Ebihara H, Branco L, Garry RF, Schwan TG, Feldmann H. Detection of Lassa Virus, Mali. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1123–1126. doi: 10.3201/eid1607.100146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Raghava GP. Prediction of continuous B-cell epitopes in an antigen using recurrent neural network. Proteins. 2006;65(1):40–48. doi: 10.1002/prot.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šali A, Potterton L, Yuan F, van Vlijmen H, Karplus M. Evaluation of comparative protein modelling by MODELLER. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinf. 1995;23:318–326. doi: 10.1002/prot.340230306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander C, Vriend G. Quality control of protein models: directional atomic contact analysis. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:47–60. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892008240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz H, Kohler B, Laue T, Drosten C, Veldkamp PJ, Gunther S, et al. Monitoring of clinical and laboratory data in two cases of imported Lassa fever. Microb Infect/Institut Pasteur. 2002;4(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal NH, Parsons DW, Peggs KS, et al. Epitope landscape in breast and colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(3):889–892. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sippl MJ. Recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:355–362. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stassar MJ, Raddrizzani L, Hammer J, et al. T-helper cell-response to MHC class II-binding peptides of the renal cell carcinoma-associated antigen RAGE-1. Immunobiology. 2001;203(5):743–755. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(01)80003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söding J. Protein homology detection by HMM–HMM comparison. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:951–960. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söding J, Biegert A, Lupas AN (2005) The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucl Acids Res 33(web Server Issue):W244–W248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thevenet P, Shen Y, Maupetit J, Guyon F, Derreumaux P, et al. PEP-FOLD: an updated de novo structure prediction server for both linear and disulfide bonded cyclic peptides. Nucl Acids Res. 2012;40:W288–W293. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDockVina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P, Sidney J, Kim Y, Sette A, Lund O, Nielsen M, Peters B. Peptide binding predictions for HLA DR, DP and DQ molecules. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11:568. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts C. Capture and processing of exogenous antigens for presentation on MHC molecules. Immunology. 1997;15:821. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe MS, Macher AM. Historical Lassa fever reports and 30-year clinical update. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(5):835–837. doi: 10.3201/eid1205.050052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.