Abstract

In estuarine and coastal ecosystems, the majority of previous studies have considered coupled nitrification-denitrification (CND) processes to be exclusively sediment based, with little focus on suspended particulate matter (SPM) in the water column. Here, we present evidence of CND processes in the water column of Hangzhou Bay, one of the largest macrotidal embayments in the world. Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that SPM was negatively correlated with nitrate (rho = −0.372, P = 0.018) and marker genes for nitrification and denitrification in the water column were detected by quantitative PCR analysis. The results showed that amoA and nir gene abundances strongly correlated with SPM (all P < 0.01) and the ratio of amoA/nir strongly correlated with nitrate (rho = −0.454, P = 0.003). Furthermore, aggregates consisting of nitrifiers and denitrifiers on SPM were also detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Illumina MiSeq sequencing further showed that ammonia oxidizers mainly belonged to the genus Nitrosomonas, while the potential denitrifying genera Bradyrhizobium, Comamonas, Thauera, Stenotrophomonas, Acinetobacter, Anaeromyxobacter, Sulfurimonas, Paenibacillus and Sphingobacterium showed significant correlations with SPM (all P < 0.01). This study suggests that SPM may provide a niche for CND processes to occur, which has largely been missing from our understanding of nitrogen cycling in estuarine waters.

Introduction

The amount of reactive nitrogen (N) ultimately ending up in estuarine and coastal ecosystems, which stems from human activity has increased extensively (over 150%) in the 20th century. Excess N has resulted in increased eutrophication across numerous estuarine ecosystems and has consequently become a global matter of concern over the last several decades1. Estuarine eutrophication has resulted in a suite of environmental problems including oxygen depletion, algae blooms, loss of biodiversity, global acidification and even the establishment of invasive species2,3. Recently, the Bulletin of China’s Marine Environmental Status (2014) showed that anthropogenic pollution is of particular concern in China, with nearly 80% of Chinese estuaries subject to some level of eutrophication. Thus, understanding N transformation, as well as removal mechanisms in estuarine systems are critical for the maintenance and conservation of estuarine ecosystem health.

N biogeochemistry, which is almost exclusively reliant on reduction-oxidation (redox) reactions, is facilitated primarily by microorganisms4. Denitrification, the sequential reduction of nitrate (NO3−) to dinitrogen gas (N2) via oxidized intermediates, is considered to be the dominant loss pathway for fixed N in shallow coastal and estuarine systems5, although anammox (the anaerobic oxidation of ammonium) has been recently identified as an alternative microbial pathway of N2 production6. Two nitrite reductases—copper-containing and cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductases (nirK and nirS) are key enzymes in the denitrification pathway7. Nitrification, the two-step conversion of ammonium (NH4+) to NO3− via nitrite (NO2−), is generally thought to play a critical role in the N cycle. Ammonia oxidation is considered to be the rate-limiting step of nitrification and is catalyzed by ammonia monooxygenase (AMO), which is encoded by the amoA gene from both archaea (AOA amoA) and bacteria (AOB amoA)8. When coupled with denitrification, nitrification partially mitigates the adverse effects of eutrophication, by removing bioavailable N from the water and releasing it to the atmosphere as N2O or N2.

In general, nitrification is an aerobic process and denitrification is an anaerobic one, and the two processes are often carried out in different ecological niches. Sediment, with substantial niche diversity (characterized by complex structural properties and sharp redox gradients), has been identified as the dominant sink for fixed N9. Coupled nitrification-denitrification (CND) processes in estuarine sediments contribute substantially to N loss, in some cases removing 10-80% of anthropogenic N pollution10. To date, there are a number of studies which have shown the importance of sediment-based CND in estuaries11,12; however there may be additional sites with comparable niche diversity in estuaries that may facilitate CND and subsequent N removal.

Strong tidal currents often resuspend fine particulates from the benthos, and the resulting suspended particulate matter (SPM) is a universal component of estuarine waters, particularly in macrotidal estuaries13. Composed of nutrients, organic micro-pollutants and heavy metals, SPM can affect material exchange and biogeochemical processes in estuarine systems14. In the maximum turbidity zone (MTZ), where primary production tends to be light-limited, the accumulating SPM is a substrate for most bacterial activity15. While a number of studies have followed the effects of particle-attached heterotrophic bacteria on estuarine carbon circulation16,17, the fate of excess N, driven by microbially-mediated processes related to SPM in estuarine environments, remains unclear. Does SPM provide adequate conditions for CND processes to occur in estuarine waters?

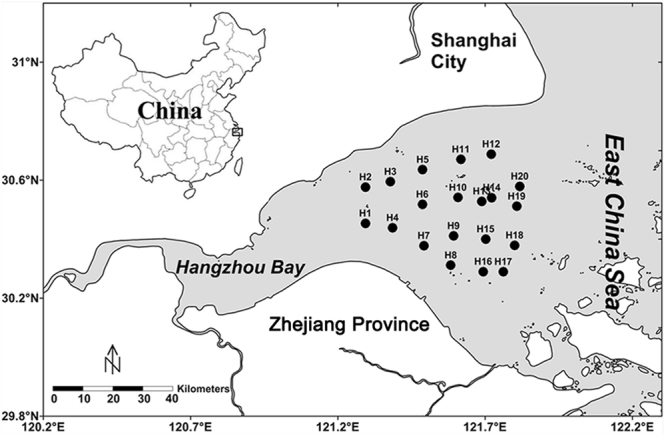

Hangzhou Bay is located in the northern Zhejiang Province of China and is adjacent to the East China Sea (Fig. 1). Covering an area of approx. 8,500 km2, it is one of the world’s largest macrotidal embayments. The tidal amplitude at the mouth is 3–4 m, and it exceeds 4–6 m further upstream. Tidal currents are mainly rectilinear and the maximal flood velocity exceeds 4.0 m/s18. Influenced by tidal currents and waves, Hangzhou Bay has a high carrying capacity for SPM, which is carried downstream from the Changjiang River and the Qiantang River19. The mean annual water discharge and sediment transport in Hangzhou Bay are 2.91 × 1010 m3 and 6.68 × 106 tons, respectively20. The purpose of this study is to investigate the potential for CND processes mediated by SPM in the water column of Hangzhou Bay and provide new insight into the role of SPM in estuarine N cycle.

Figure 1.

Map of Hangzhou Bay, China showing sampling sites on the west coast of the East China Sea. The Surfer 11 software (http://www.goldensoftware.com/products/surfer) was used to generate the map.

Results

Environmental parameters and correlation analyses

Environmental parameters in the water column of Hangzhou Bay are shown in Supplementary Table S1, across a scale of ~55 km. Ranging from 0.02 to 8.07 g/L, SPM of the surface water was significantly lower than that of the bottom water (Table 1; F(1,39) = 26.869, P = 0.000) and the opposite result was seen for particulate organic carbon (POC) (Table 1; F(1,39) = 40.301, P = 0.000). NO3− accounted for 95.85–99.80% of the dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) in the water column. However, NO3− of the surface water was significantly higher than that of the bottom water (Table 1; F(1,39) = 6.110, P = 0.018). The remaining environmental parameters, including temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, chlorophyll a (Chl a), NH4+ and NO2−, showed no significant differences between the surface and bottom water of Hangzhou Bay (Table 1).

Table 1.

Means (±SD) of environmental parameters for samples taken from the surface and bottom waters and results of the one-way ANOVA (F) showing significant differences in environmental parameters with depth.

| Depth | Temperature | Salinity | DO | pH | Chl a | SPM | POC | NH4+ | NO2− | NO3− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | (°C) | (ppt) | (mg/L) | (μg/L) | (g/L) | (g/g) | (μM) | (μM) | (μM) | ||

| mean ± SDa | 0.05 ± 0.00 | 20.27 ± 1.47 | 21.77 ± 5.08 | 6.21 ± 0.70 | 8.01 ± 0.02 | 0.65 ± 0.32 | 0.36 ± 0.25 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.6 | 0.12 ± 0.10 | 119.07 ± 16.22 |

| mean ± SDb | 9.80 ± 2.24 | 19.57 ± 0.93 | 22.51 ± 4.69 | 6.16 ± 0.78 | 8.00 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.2 | 2.64 ± 1.95 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 1.03 ± 1.02 | 0.16 ± 0.10 | 98.38 ± 33.73 |

| F | 345.233 ** | 3.237 | 0.230 | 0.053 | 2.967 | 0.323 | 26.869 ** | 40.301 ** | 0.186 | 1.455 | 6.110 * |

| rho | 0.760 ** | −0.436 ** | 0.152 | −0.029 | −0.209 | −0.161 | — | −0.706 ** | 0.027 | 0.345 * | −0.372 * |

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho) between SPM concentration and other environmental parameters of the entire water column (pooled surface + bottom) are also presented.

aEnvironmental parameters of surface water column.

bEnvironmental parameters of bottom water column.

Data in bold indicate significant correlations, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Spearman’s correlation analyses between SPM and other environmental parameters (pooled surface and bottom) were performed (Table 1; N = 40). Strong positive correlation was identified between SPM and depth (Table 1; rho = 0.760, P = 0.000) and strong negative correlations were identified between SPM and both temperature and POC (Table 1; rho = −0.436, P = 0.005 and rho = −0.706, P = 0.000). Furthermore, NO2− and NO3− showed weak correlations with SPM (Table 1; rho = 0.345, P = 0.029 and rho = −0.372, P = 0.018), while no relationship between SPM and NH4+ was observed. It is worth noting that no correlation was found between SPM and NO3− in surface water (N = 20) or bottom water (N = 20) when compared alone (data not shown).

Abundances of nitrifying and denitrifying genes and correlation analyses

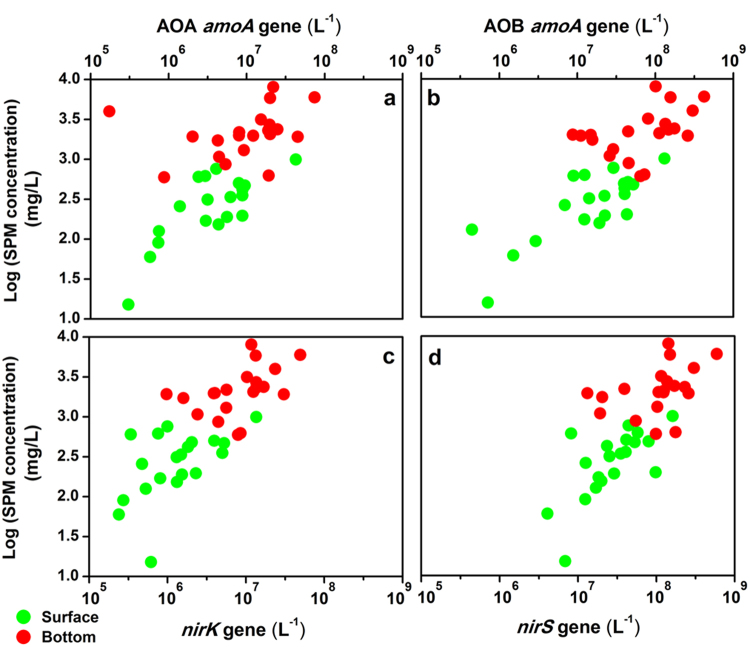

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis was used to estimate the abundances of the key nitrifying (AOA amoA and AOB amoA) and denitrifying (nirK and nirS) genes in the water samples obtained from the study area. Among the nitrifying genes, at each site, the abundance of AOB amoA gene (4.46 × 105−4.22 × 108 copies/L) was higher than that of AOA amoA gene (1.74 × 105−7.43 × 107 copies/L), with the exception of sample H4_S (Supplementary Table S2). Among the denitrifying genes, nirS gene appeared to be more numerous, with copy numbers ranging from 4.07 × 106 to 5.90 × 108 per liter of water, while copy numbers of nirK gene ranged from 2.39 × 105 to 4.95 × 107 per liter of water (Supplementary Table S2). The relative nirS/nirK ratios ranged from 6.90 to 76.29 in all samples, showing the clear dominance of nirS gene in the water column of Hangzhou Bay. Moreover, along the SPM gradient, both nitrifying and denitrifying genes showed significantly higher abundance of the bottom water than that of the surface water (Fig. 2). In addition, the abundance of anammox bacterial 16 S rRNA gene, ranging from 3.29 × 104 to 9.81 × 106 copies/L, was 1~2 orders of magnitude lower than the abundances of nir genes (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 2.

The abundances and distributions of (a) AOA amoA, (b) AOB amoA, (c) nirK and (d) nirS genes along SPM concentration gradient in Hangzhou Bay surface (N = 20) and bottom (N = 20) water column.

In order to explore the relationships between gene abundances and environmental parameters, Spearman’s correlation analyses were performed (Table 2; N = 40). The abundances of all functional genes showed strong positive correlations with SPM and depth (Table 2; all P < 0.01). Furthermore, negative correlations between NO3− and AOB amoA and nirK gene abundances (Table 2; rho = −0.320, P = 0.044 and rho = −0.323, P = 0.042) were observed; however, no significant correlation was found between NO3− and AOA amoA or nirS gene abundance (Table 2). Temperature and POC were also found to be negatively correlated with the abundances of all functional genes (Table 2; P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). Analyses of the gene copy ratios showed that the ratios of AOB amoA/AOA amoA and nirK/nirS were positively correlated with SPM (Table 2; rho = 0.495, P = 0.001 and rho = 0.403, P = 0.010), and negatively correlated with POC and NO3− (Table 2; P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). In addition, amoA/nir value showed strong negative correlation with NO3− (Table 2; rho = −0.454, P = 0.003).

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (rho) between environmental parameters and gene abundances and the ratios of target genes across sampling sites (pooled surface + bottom samples).

| Depth | Temperature | Salinity | DO | pH | Chl a | SPM | POC | NH4+ | NO2− | NO3− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | (°C) | (ppt) | (mg/L) | (μg/L) | (g/L) | (g/g) | (μM) | (μM) | (μM) | ||

| Abundance | |||||||||||

| AOA amoA | 0.397 ** | −0.397 * | 0.180 | −0.033 | −0.012 | −0.060 | 0.601 ** | −0.390 ** | 0.056 | 0.203 | −0.084 |

| AOB amoA | 0.562 ** | −0.526 ** | 0.268 | −0.111 | 0.105 | −0.230 | 0.697 ** | −0.467 ** | −0.087 | 0.190 | −0.320 * |

| nirK | 0.644 ** | −0.416 ** | 0.153 | −0.171 | 0.007 | −0.127 | 0.775 ** | −0.586 ** | −0.150 | 0.175 | −0.323 * |

| nirS | 0.548 ** | −0.395 * | 0.128 | −0.088 | −0.073 | −0.132 | 0.746 ** | −0.546 ** | −0.136 | 0.127 | −0.178 |

| Ratio | |||||||||||

| AOB amoA/AOA amoA | 0.476 ** | −0.414 ** | 0.286 | 0.026 | 0.133 | −0.226 | 0.495 ** | −0.342 * | 0.056 | 0.073 | −0.339 * |

| nirK/nirS | 0.459 ** | −0.269 | 0.192 | −0.304 | 0.233 | −0.122 | 0.403 ** | −0.316 * | −0.145 | −0.022 | −0.427 ** |

| amoAa/nirb | 0.153 | −0.491 ** | 0.345 * | −0.252 | 0.280 | −0.274 | 0.249 | −0.118 | 0.196 | 0.176 | −0.454 ** |

aRepresents the sum of AOB amoA and AOA amoA gene abundances.

bRepresents the sum of nirK and nirS gene abundances.

Data in bold indicate significant correlations, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Bacterial community structures and RDA analysis

The Illumina MiSeq platform produced ~1,500,000 raw reads of the V4 amplicons. After removing the short and low-quality reads, 34,117–69,053 bacterial reads of each sample were available for further analyses. The numbers of OTUs, Chao 1 and Shannon’s indices at cutoff levels of 3% are summarized in Supplementary Table S3. On the basis of OTU numbers, the H7_B sample had the richest abundance, and declined to less than half that in H19_S sample. The comparison between surface and bottom water samples showed that the latter contained more bacterial richness than the former at most of the sampling sites (Supplementary Table S3). Very similar trends in the Chao 1 index were observed in comparison with OTU richness (Supplementary Table S3). Shannon diversity indices also indicated a higher bacterial diversity for the bottom water samples relative to the surface at all the sampling sites (Supplementary Table S3).

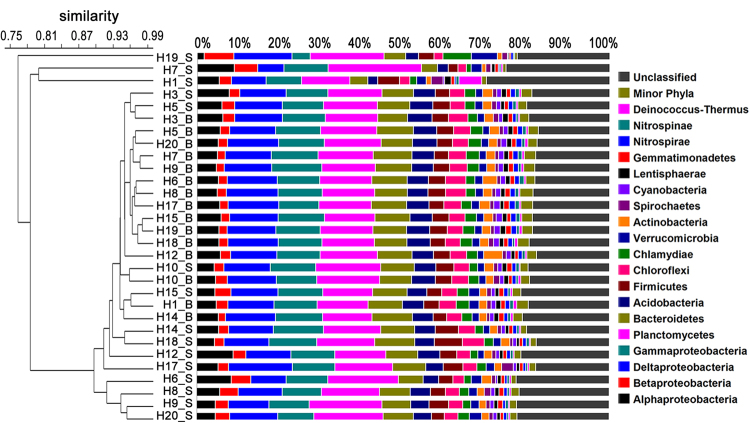

Cluster analysis at the phylum level revealed similarities of bacterial community structure in each sample of Hangzhou Bay (Fig. 3). In contrast to the surface water layer, bacterial communities in the bottom water layer were relatively stable and showed little variability, with almost all samples clustering together (Fig. 3). Proteobacteria was the most abundant phylum across all water samples, accounting for 28.56–35.32% of the total effective bacterial sequences. Within the Proteobacteria group, Deltaproteobacteria (6.37–15.52%, averaging 11.36%) was the most dominant class, followed by Gammaproteobacteria (4.44–12.19%, averaging 10.34%), Alphaproteobacteria (1.61–8.94%, averaging 5.41%) and Betaproteobacteria (1.73–7.19%, averaging 2.92%). The other dominant phyla were Planctomycetes (11.73–22.69%, averaging 14.10%), Bacteroidetes (3.86–9.82%, averaging 7.76%), followed by a few other major phyla (abundance >1% in each sample), including: Acidobacteria, Firmicutes, Chloroflexi, Chlamydiae and Verrucomicrobia. A few phyla (e.g. Actinobacteria, Spirochaetes, Cyanobacteria, Lentisphaerae, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospirae, Nitrospinae and Deinococcus-Thermus) were only major contributors (abundance >1%) to phyletic compositions of single samples.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram of hierarchical clustering of bacterial community structure based on Bray-Curtis similarity. Bacterial taxonomic information is shown at the phylum level (and subdivision level for Proteobacteria). Taxa represented occurred at >1% abundance in at least one sample. Minor phyla refer to the taxa with their maximum abundance <1% in any sample.

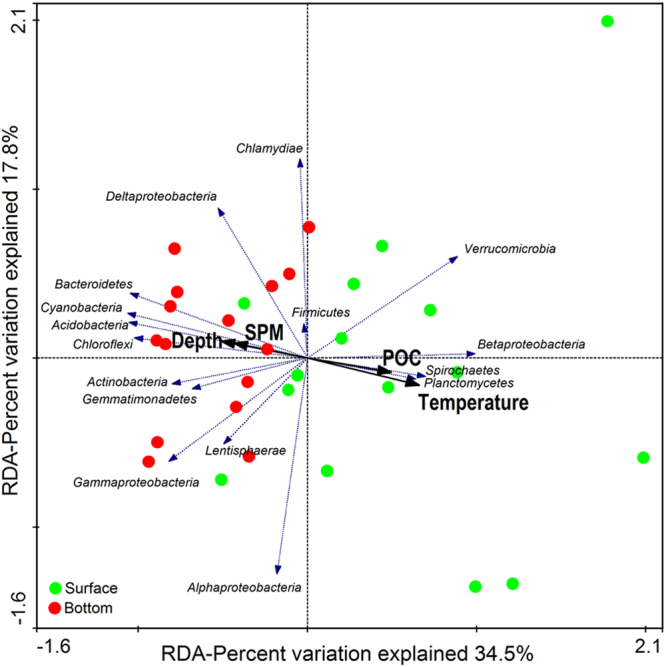

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted to identify the potential effect of environmental parameters on bacterial community patterns. Overall, the first two RDA axes explained 52.3% of the total variation, and RDA1 axis clearly distinguished the bacterial distributions of surface water from that of bottom water. Of all the environmental parameters measured, depth (F = 5.492, P = 0.001), temperature (F = 5.150, P = 0.005), SPM (F = 3.836, P = 0.033) and POC (F = 10.413, P = 0.001) appeared to be the major drivers influencing bacterial distributions, while other variables (e.g., salinity, DO, pH, Chl a, NH4+, NO2− and NO3−) had weaker effects on bacterial assemblages (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Redundancy analysis of the relationship between environmental parameters (black arrows) and bacterial community distributions of surface (green circles) and bottom (red circles) water column of Hangzhou Bay. Taxonomic information is shown at the phylum level (and subdivision level for Proteobacteria). Only P value of environmental parameter <0.05 (999 times Monte-Carlo permutation test) and average abundance of taxa >1% are shown.

Sequences belong to nitrifying and potential denitrifying genera

Taxonomically, AOB are phylogenetically restricted to two lineages within the Proteobacteria: the Betaproteobacteria, including the genera Nitrosomonas, Nitrosospira, Nitrosovibrio and Nitrosolobus21; and the Gammaproteobacteria, including the genus Nitrosococcus22. The Betaproteobacterial Nitrosomonas and Nitrosospira, and the Gammaproteobacterial Nitrosococcus were observed in this study. The Nitrosomonas and Nitrosococcus groups were the two dominant genera of AOB, accounting for 0.06–5.25% and 0.03–0.17% of the total sample sequences respectively, while the genus Nitrosospira was nearly absent in this study (Supplementary Figure S1a). In addition, the relative abundance of Nitrosomonas showed strong negative correlations with SPM, NO2− and AOB amoA gene (Supplementary Table S4; all P < 0.01), and a weak positive correlation with NO3− (Supplementary Table S4; rho = 0.442, P = 0.014). While, the relative abundance of Nitrosococcus was only positively correlated with SPM (Supplementary Table S4; rho = 0.422, P = 0.020).

Previous studies provided a list of ~100 denitrifying bacterial genera23–26, among which 44 genera were detectable in the water column of Hangzhou Bay (Supplementary Figure S1b). In this study, the majority of the potential denitrifying genera belonged to Proteobacteria (31 genera; 0.47–1.61% of the total 16 S rRNA sequences). The second largest group of denitrifiers was categorized as Bacteroidetes (4 genera; 0.17–0.83%), followed by the group of Firmicutes (5 genera; 0.08–0.46%) and Actinobacteria (4 genera; 0–0.05%) (Supplementary Figure S1b). Among the 44 denitrifying genera, many of them showed strong positive correlations with SPM (P < 0.01), which mainly included (i.e. average abundance >0.05%) the genera Bradyrhizobium of Alphaproteobacteria; Comamonas and Thauera of Betaproteobacteria; Stenotrophomonas and Acinetobacter of Gammaproteobacteria; Anaeromyxobacter of Deltaproteobacteria; Sulfurimonas of Epsilonproteobacteria; Paenibacillus of Firmicutes; and Sphingobacterium of Bacteroidetes (Supplementary Table S5).

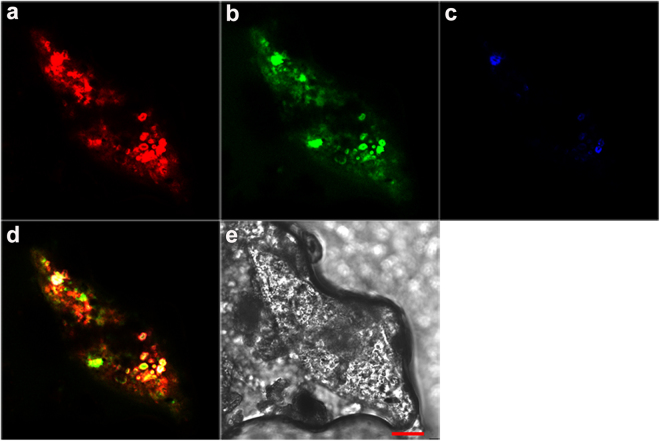

In situ characterization of nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria

The presence of nitrifiers and denitrifiers in the bacterial consortia of the SPM was examined by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. In situ hybridization clearly indicated that AOB and denitrifiers were not uniformly distributed within the SPM, and AOB were in greater abundance than acetate/methanol-denitrifying cells (Fig. 5a–c and Supplementary Figures S2a–c). Specifically, the majority of NSO190 probe-stained AOB and DEN124 probe-stained acetate-denitrifying cells formed irregularly shaped (2–10 μm), dense aggregates, with ammonia-oxidizing microcolonies found mainly in the outer part of the aggregate and acetate-denitrifying cells in the middle (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Figure S2d). Though fewer cells hybridizing with probe DEN67 were detected (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figure S2c), the white signals in the figures indicated that the methanol-denitrifying cells also existed in inner sections of the aggregates.

Figure 5.

Simultaneous in situ hybridization of SPM samples in the water column of Hangzhou Bay. Fluorescence micrograph of (a) ammonia-oxidizing bacteria hybridization with Cy3-labeled probe NSO190 (red); (b) acetate-denitrifying cluster hybridization with FAM-labeled probe DEN124 (green); (c) methanol-denitrifying cluster hybridization with Cy5-labeled probe DEN67 (blue); (d) combined image of the three fluorescence micrographs, where the yellow cell aggregates are double labeled with NSO190 and DEN124, and the white cell aggregates are tripled labeled with NSO190, DEN124 and DEN67. A phase contrast-micrograph of the floc section, where the red bar = 20 μm, is depicted in (e).

Discussion

Although a previous study has shown that NH4+ is the primary anthropogenic nutrient entering Hangzhou Bay from the Qiantang River27, NO3− was found to be the most important form of DIN in the water column of Hangzhou Bay. Chl a concentrations (0.26–1.75 μg/L) in the water column were much lower than those measured in other estuaries28,29, and is likely indicative of poor light availability which severely limits phytoplanktonic uptake of NH4+ 30. Furthermore, no negative relationship between Chl a and NH4+ or NO3− was found (data not shown). It is likely that microbial nitrification is a key process for the fate of NH4+ in the water column. SPM was found to be negatively correlated with NO3− and positively correlated with NO2−, potentially linking SPM-attached denitrifiers to nitrate reduction. We investigated these possibilities by quantifying the abundances of nitrifiers and denitrifiers in the water column and tested their relationships with the measured environmental parameters. High abundances of amoA and nir genes were detected in both the surface and bottom layers of the water column, with the abundances of AOB amoA and nirK genes and the ratio of amoA/nir significantly correlating with NO3−, showing links between nitrifiers/denitrifiers and available N31. Although correlations between SPM and indicators of denitrifying bacteria do not necessarily indicate causation, these results provide insight on the potential possibility of SPM to act as an important site for CND processes in the water column of Hangzhou Bay.

Crucial environmental parameters known to influence abundance and diversity of nitrifiers and denitrifiers mainly include temperature, salinity, oxygen and nutrient availability5,32. Nevertheless, in this study, the abundances of nitrifying and denitrifying genes were strongly correlated with SPM concentration. Moreover, the results of the RDA suggested that SPM played an important role in shaping the bacterial communities in the water column. In particular, the phyla (or class) Bacteroidetes, Planctomycetes and Deltaproteobacteria were the dominant community members and have recently been shown to be associated with larger particle size fractions33. Overall, these results suggest that SPM may provide a large area for nitrifiers and denitrifiers to co-exist, shaping nitrifying and denitrifying communities in estuarine water. Meanwhile, aggregates consisting of outer nitrifiers and inner denitrifiers detected by FISH analysis indicate that anoxic/low oxygen microsites probably exist inside the SPM. According to Jia et al. (2016), high O2 influx around suspended particles and decreasing DO concentration suggested that oxygen was being consumed near the particle’s surface by nitrification and/or microbial respiration34. They reported that particles with diameters <20 μm had the largest overall increase in O2 influx. Schramm et al. had also reported that the volumetric respiration rate was negatively correlated with floc size35. Accordingly, SPM in Hangzhou Bay is predominantly composed of fine and medium silt, and the grain size of over 90% of the SPM is less than 20 μm18,36. FISH analyses in the present study support this, showing that the size of most aggregates on SPM were far less than 20 μm (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Figure S2). Based on these results, we suggest that SPM could not only provide large areas for the co-existence of nitrifiers and denitrifiers, but may also provide redox conditions for CND processes to occur in oxic water.

Numerous earlier studies suggest that AOA phylotypes are more abundant than AOB in estuarine ecosystems37,38. However, our qPCR estimates indicated that the abundance of bacterial amoA gene was higher than that of archaeal amoA gene in all samples (with a single exception). Moreover, the abundance of AOB amoA gene significantly correlated with NO3−, while the abundance of AOA amoA gene did not. Thus, it is possible that nitrification may be driven by bacteria rather than archaea in the water column of Hangzhou Bay. Furthermore, the abundance of Nitrosomonas was positively correlated with NO3− and negatively correlated with NO2−, suggesting it may be the predominant AOB during nitrification process. Similar to previous studies, members of the Nitrosomonas group appear to be dominant in most terrestrial and aquatic environments39. Despite Nitrosomonas being the most dominant AOB in the water column, the genus Nitrosococcus was dominant in the sediment (Supplementary Figure S3). This may partly explain why the abundance of Nitrosomonas was negatively correlated with SPM.

Since the concentration of Chl a in the water column was very low, it seemed unlikely that nitrate was assimilated by algae. Additionally, the abundance of nirK gene was negatively correlated with NO3−, while the nirS gene was not. Thus, it is possible that the decrease of nitrate concentration in the system is mainly caused by nirK-type denitrifiers on SPM. Though nirS gene appears to be more abundant in nature40, the activity of cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductases (NirS) was more likely to be repressed than that of copper-containing nitrite reductases (NirK) in the oxic water of Hangzhou Bay. As Körner and Zumft (1989)41 pointed out, the threshold values for synthesis of copper-containing nitrite reductases (NirK) was 5 mg of O2 per liter, and several studies from different environments have also shown that bacteria carrying the nirK gene were not particularly sensitive to oxygen42,43. The higher abundance of nirS gene in the water column of Hangzhou Bay was probably a result of sediment resuspension, as the abundance of nirS-type denitrifiers (1.90 × 106–4.69 × 107 copies/g dry sediment) was much higher than that of nirK-type denitrifiers (1.21 × 104−3.27 × 106 copies/g dry sediment) in the sediment of Hangzhou Bay (Supplementary Figure S4). While not definitive, many of the denitrifying genera identified in this study showed strong positive correlations with SPM, and are potentially indicative of denitrification process, providing a new direction for inquiry into CND processes in aerobic water columns.

Recently, a series of 15N isotopic tracer studies have suggested that the nitrification/denitrification rates in oxic water are significantly affected by the abundances of nitrifiers/denitrifiers on the suspended particles44–47. Although the current study did not make direct measurement of nitrification or denitrification rate, on the basis of results above, we assume that the abundances of nitrifiers/denitrifiers on SPM can also reflect (to some extent) nitrification/denitrification rates in the turbid water of Hangzhou Bay. The microbial mechanisms behind CND processes are potentially as follows: in the case of water column with high oxygen concentration, SPM can provide large areas for the co-existence of nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria. As is known to all, NO2− is difficult to accumulate in the oxic environment and will finally be oxidized to NO3−. With the number of AOB being far greater than that of nirK-type denitrifiers, it is not NO2− but NO3− that accumulated in the system, accounting for 95.85–99.80% of the total inorganic nitrogen. When SPM increased, more low/anoxic microsites could be generated, caused by respiration of heterotrophic bacteria and transport limitations34. Although overall, the number of AOB significantly increased, the abundance of Nitrosomonas (the dominant AOB) itself, significantly decreased, leading to the decrease in NO3− production. Meanwhile, the number of nirK-type denitrifiers significantly increased, and the increase of both low/anoxic microsites and denitrifiers within the SPM promotes denitrification, leading to the increase in NO3− removal. In combination, both processes eventually resulted in a significant decrease in NO3− (Supplementary Figure S5). Correspondingly, the decrease of POC concentration suggested an increasing consumption of POC by denitrification and/or heterotrophic bacterial respiration.

With the caveat that correlations between SPM and indicators of denitrifying bacteria do not necessarily indicate causation, the current study reports for the first time that SPM may provide the conditions for CND processes to occur in the water column of Hangzhou Bay. These preliminary insights on the coupling of nitrification and denitrification processes mediated by SPM, help to resolve our understanding of N cycle in estuarine ecosystems. High SPM concentration, caused by erosion and bottom sediment resuspension, could accelerate N transformation and the subsequent removal processes in turbid estuaries and should be included in budgets of riverine N flux to coastal oceans. The findings shed further light on our conceptual views of N fluxes and transformation in estuarine ecosystems and provide another avenue of consideration with respect to CND processes. However, the paucity of direct measurements of CND rates of SPM hinders further interpretations of this current dataset. Quantifying the relationship between direct measurements of nitrification/denitrification rates of SPM and the associated microorganisms, through the application of 15N isotopic tracer technologies for example, may help to elucidate how these coupling processes respond to SPM variability in the turbid estuarine waters.

Materials and Methods

Sampling

Samples of surface (at 0.5 m depth) and bottom water (1 m above the benthos) were collected from twenty sites along Hangzhou Bay during a 7 day cruise in May 2014, when the phytoplankton quantity was quite low48 (Fig. 1). All water samples were collected with a 5-L Niskin bottle (Tianjin test center, Tianjin, China), and then sampled from the Niskin bottle with a plastic syringe. Standard oceanographic properties including water temperature, salinity, DO and pH were measured immediately using a Horiba U-52 water quality checker (Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). The concentrations of Chl a (µg/L), SPM (g/L), POC (g per g SPM) and nutrients (NH4+, NO2− and NO3−; µM) were measured following standard protocols49. Water samples for nucleic acids analysis and SPM samples for FISH analysis were collected onto 0.2-μm and 0.45-μm polycarbonate GTTP membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) respectively and preserved at −80 °C.

DNA extraction

Total nucleic acids of the water samples were extracted directly from the 0.2-μm membranes using a FastDNA spin kit for soil (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Duplicate DNA extractions for each water sample were performed. DNA quality was detected through 1% agarose gel electrophoresis which was stained with SYBR Safe DNA Gel Stain (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The duplicate DNA extractions were then merged together, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent molecular analysis.

QPCR analysis

To examine the spatial variation of community size for nitrifying and denitrifying groups in the water column of Hangzhou Bay, the abundances of AOA amoA, AOB amoA, nirK and nirS genes were quantified using qPCR. Serial tenfold dilutions (10−1 to 10−5) of linearized plasmids containing cloned AOA amoA, AOB amoA, nirK and nirS genes were used to obtain standard curves. All sample and standard reactions were performed in triplicate using CFX 96 C 1000TM Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and average values were calculated. Each reaction was performed in 20 μL containing 2 μL of total DNA template, 0.4 μL of each primer (10 mM) and 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S6. The PCR cycle started with 3 min at 95 °C, followed by a total of 40 cycles of 10 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 55 °C for AOB amoA gene (57 °C for AOA amoA and nirS genes, and 58 °C for nirK gene) and 30 s at 72 °C. The specificity of amplification was checked by the observation of melt curves. PCR amplification efficiencies were 83–100.7% with correlation coefficients (R2) over 0.99 for all calibration curves.

Illumina MiSeq sequencing and sequence analysis

Bacterial communities were investigated at 15 sites for both surface and bottom layers of the water column of Hangzhou Bay, using high-throughput sequencing according to the protocols described by Caporaso et al.50. The V4 regions of bacterial 16 S rRNA gene were amplified from the DNA extracts using primers 520 F (5′-barcode-AYTGGGYDTAAAGNG-3′) and 802 R (5′-TACNVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). The barcode is a seven-base sequence unique to each sample. A 25 μL reaction contained 1.25 U of Q5 polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), 5 μL Q5 reaction buffer (5×), 5 μL Q5 GC high Enhancer (5×), 0.2 mM of dNTPs (TaKaRa), 0.4 mM of each primer and 40 ng of total DNA. PCR amplification was conducted under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 5 min; 27 cycles at 98 °C for 30 s, 50 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 30 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. PCR amplicons were purified using AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kits (Axygen, Union City, CA, USA) and quantified on a FLx800 Fluorescence Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). Amplicons from different water samples were then pooled to achieve equal mass concentrations in the final mixture, which was sent out for high-throughput sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Personalbio, Shanghai, China). Sequences are available in the NCBI short-read archive database (Accession Number: SRP091596).

The sequencer generated 1,459,768 reads of 16 S rRNA gene from 30 samples. Raw sequences were de-multiplexed and quality-filtered using the default parameters in Qiime version 1.7.051. Criteria used for the filtering step were recommended by Bokulich et al.52. The remaining PCR chimeras were removed using the uchime method in mothur version 1.31.253. Bacterial sequences were then clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs; 97% similarity) with uclust in Qiime54. A bootstrap cutoff of 50% suggested by the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) was applied for taxonomic assignment55. On the basis of OTU numbers, the alpha diversity measures (Chao 1 and Shannon index) were calculated in mothur56.

FISH analysis

SPM samples were fixed on ice for 3 h in freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde solution and subsequently rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline. For in situ hybridization, 4 µL of each fixed sample was spotted onto adhesion microscope slides. Hybridization of the SPM samples was performed according to the procedure described by Amann (1995)57. Three 16 S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes were used for in situ detection of nitrifying and denitrifying bacteria: (1) Cy3-labeled NSO190 probes: specific for ammonia-oxidizing β-subclass Proteobacteria (2) Cy5-labeled DEN67 probes: specific for methanol-denitrifying cluster and (3) FAM-labeled DEN124 probes: specific for acetate-denitrifying cluster. The specificities, sequences and hybridization conditions of all probes are shown in Supplementary Table S7. All hybridizations were performed at a temperature of 50 °C. Subsequently, fluorescent and phase-contrast images were recorded using a multiphoton confocal LSM 780 NLO microscope system (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

Data analysis

To assess the variations in environmental parameters between surface and bottom water layers, we used a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Most of the variables were non-normal, except Chl a and NO3−. Spearman’s correlation analyses were used to test the correlations between SPM and other environmental parameters (depth, temperature, salinity, DO, pH, Chl a, POC, NH4+, NO2− and NO3−); between gene abundances (or gene copy ratios) and environmental parameters (depth, temperature, salinity, DO, pH, Chl a, SPM, POC, NH4+, NO2− and NO3−); between the abundance of nitrifying genera and SPM, NH4+, NO2−, NO3− and AOB amoA gene abundance; and finally between the abundance of denitrifying genera and SPM. All calculations were performed using IBM SPSS statistics 20.0 software.

To compare the bacterial community in different samples, hierarchical clustering was performed in the program PAST58 based on Bray-Curtis similarity index and unweighted pair group method average (UPGMA) algorithm. To test the influences of environmental parameters (depth, temperature, salinity, DO, pH, Chl a, SPM, POC, NH4+, NO2− and NO3−) on the distributions of bacterial phylotypes, redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed using the software Canoco 5.059. To meet assumptions, all measured environmental parameters were standardized before analyses.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Public Science and Technology Research Funds Projects of Ocean (201005030) and the National Science Foundation of China (41476156, 41321004).

Author Contributions

Z.W.J., and W.W.X. designed and conducted the experiments. Z.W.J. and W.C. wrote the main manuscript text. Z.W.J. and H.Y.Y. performed the experiments. W.W.X., M.Z.H., T.B.Y. and J.H. contributed to the data analysis and manuscript revision and language editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript and have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Weijing Zhu and Cheng Wang contributed equally to this work

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20688-4.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Zhihua Mao, Email: mao@sio.org.cn.

Weixiang Wu, Email: weixiang@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Herbert RA. Nitrogen cycling in coastal marine ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 1999;23:563–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1999.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabalais NN. Nitrogen in aquatic ecosystems. AMBIO. 2002;31:102–112. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gruber N, Galloway JN. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature. 2008;451:293–296. doi: 10.1038/nature06592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Falkowski PG. Evolution of the nitrogen cycle and its influence on the biological sequestration of CO2 in the ocean. Nature. 1997;387:272–275. doi: 10.1038/387272a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosier AC, Francis CA. Denitrifier abundance and activity across the San Francisco Bay estuary. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2010;2:667–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward BB, et al. Denitrification as the dominant nitrogen loss process in the Arabian Sea. Nature. 2009;461:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature08276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallin S, Lindgren PE. PCR detection of genes encoding nitrite reductase in denitrifying bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:1652–1657. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1652-1657.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosier AC, Francis CA. Relative abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in the San Francisco Bay estuary. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:3002–3016. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jørgensen, B. B. Eutrophication in Coastal Marine Ecosystems (eds. Richardson, K. & Jørgensen, B.B) 115–135 (American Geophysical Union, 1996).

- 10.Seitzinger SP. Denitrification in freshwater and coastal marine ecosystems: ecological and geochemical significance. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1988;33:702–724. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zopfi J, Kjær T, Nielsen LP, Jørgensen BB. Ecology of Thioploca spp.: Nitrate and sulfur storage in relation to chemical microgradients and influence of Thioploca spp. on the sedimentary nitrogen cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:5530–5537. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5530-5537.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sayama M, Risgaard-Petersen N, Nielsen LP, Fossing H, Christensen PB. Impact of bacterial NO3− transport on sediment biogeochemistry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:7575–7577. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7575-7577.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wollast, R. The major Biogeochemical Cycles and their Interactions (eds. Bolin, B. & Cook, R.B.) 385–407 (John Wiley & Sons, 1983).

- 14.Turner A, Millward GE. Suspended particles: their role in estuarine biogeochemical cycles. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2002;55:857–883. doi: 10.1006/ecss.2002.1033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muylaert K, Sabbe K. Spring phytoplankton assemblages in and around the maximum turbidity zone of the estuaries of the Elbe (Germany), the Schelde (Belgium/The Netherlands) and the Gironde (France) J. Marine Syst. 1999;22:133–149. doi: 10.1016/S0924-7963(99)00037-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abril G, Etcheber H, Delille B, Frankignoulle M, Borges AV. Carbonate dissolution in the turbid and eutrophic Loire estuary. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003;259:129–138. doi: 10.3354/meps259129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baltar F, Arístegui J, Gasol JM, Sintes E, Herndl GJ. Evidence of prokaryotic metabolism on suspended particulate organic matter in the dark waters of the subtropical North Atlantic. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2009;54:182–193. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.1.0182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie DF, Wang ZB, Gao S, De Vriend HJ. Modeling the tidal channel morphodynamics in a macro-tidal embayment, Hangzhou Bay, China. Cont. Shelf Res. 2009;29:1757–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2009.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou XJ, Gao S. Spatial variability and representation of seabed sediment grain sizes: An example from the Zhoushan-Jinshanwei transect, Hangzhou Bay, China. Chinese Sci. Bull. 2004;49:2503–2507. doi: 10.1007/BF03184286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker HJ. Geomorphological development and sedimentation in Qiantang Estuary and Hangzhou Bay. J. Coastal Res. 1990;6:559–572. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Purkhold U, et al. Phylogeny of all recognized species of ammonia oxidizers based on comparative 16 S rRNA and amoA sequence analysis: implications for molecular diversity surveys. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:5368–5382. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5368-5382.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward BB, O’Mullan GD. Worldwide distribution of Nitrosococcus oceani, a marine ammonia-oxidizing γ-proteobacterium, detected by PCR and sequencing of 16 S rRNA and amoA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:4153–4157. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.8.4153-4157.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heylen K, et al. Cultivation of denitrifying bacteria: optimization of isolation conditions and diversity study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:2637–2643. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2637-2643.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapleigh, J. P. The Prokaryotes (eds Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.H. & Stackebrandt, E.) 769–792 (Springer-Velag, 2006).

- 25.Yu Z, Yang J, Liu LM. Denitrifier community in the oxygen minimum zone of a subtropical deep reservoir. PloS One. 2014;9:e92055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong F, et al. Bacterial community analysis by PCR-DGGE and 454-pyrosequencing of horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetlands with front aeration. Appl. Microbiol. Biot. 2015;99:1499–1512. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu BL, et al. Distribution and diversity of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in the sediments of the Qiantang River. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2012;4:540–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzumura M, Kokubun H, Arata N. Distribution and characteristics of suspended particulate matter in a heavily eutrophic estuary, Tokyo Bay, Japan. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004;49:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell BJ, Kirchman DL. Bacterial diversity, community structure and potential growth rates along an estuarine salinity gradient. ISME J. 2013;7:210–220. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia XH, Yang ZF, Zhang XQ. Effect of suspended-sediment concentration on nitrification in river water: importance of suspended sediment-water interface. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:3681–3687. doi: 10.1021/es8036675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo GX, Deng H, Qiao M, Yao HY, Zhu YG. Effect of long-term wastewater irrigation on potential denitrification and denitrifying communities in soils at the watershed scale. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:3105–3113. doi: 10.1021/es304714a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santoro AE, Boehm AB, Francis CA. Denitrifier community composition along a nitrate and salinity gradient in a coastal aquifer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006;72:2102–2109. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.3.2102-2109.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fontanez KM, Eppley JM, Samo TJ, Karl DM, Delong EF. Microbial community structure and function on sinking particles in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:469. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xia, X. H. et al. Enhanced nitrogen loss from rivers through coupled nitrification-denitrification caused by suspended sediment. Sci. Total Environ. (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Schramm A, et al. On the occurrence of anoxic microniches, denitrification, and sulfate reduction in aerated activated sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999;65:4189–4196. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.4189-4196.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ru, R. Z. The statistical analysis of suspended sediment particle sizes in the Hangzhou Bay. Donghai Mar. Sci. 20, 14–19 (in Chinese) (2002).

- 37.Caffrey JM, Bano N, Kalanetra K, Hollibaugh JT. Ammonia oxidation and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea from estuaries with differing histories of hypoxia. ISME J. 2007;1:660–662. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abell GC, et al. Archaeal ammonia oxidizers and nirS-type denitrifiers dominate sediment nitrifying and denitrifying populations in a subtropical macrotidal estuary. ISME J. 2010;4:286–300. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zehr JP, Ward BB. Nitrogen cycling in the ocean: new perspectives on processes and paradigms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:1015–1024. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.3.1015-1024.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Braker G, Zhou J, Wu L, Devol AH, Tiedje JM. Nitrite reductase genes (nirK and nirS) as functional markers to investigate diversity of denitrifying bacteria in Pacific Northwest marine sediment communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:2096–2104. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2096-2104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Körner H, Zumft WG. Expression of denitrification enzymes in response to the dissolved oxygen level and respiratory substrate in continuous culture of Pseudomonas stutzeri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1989;55:1670–1676. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.7.1670-1676.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Desnues C, et al. Seasonal and diel distributions of denitrifying and bacterial communities in a hypersaline microbial mat (Camargue, France) Water Res. 2007;41:3407–3419. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knapp CW, Dodds WK, Wilson KC, O’Brien JM, Graham DW. Spatial heterogeneity of denitrification genes in a highly homogenous urban stream. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:4273–4279. doi: 10.1021/es9001407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia XH, et al. Nitrification in natural waters with high suspended-solid content—a study for the Yellow River. Chemosphere. 2004;57:1017–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu T, Xia XH, Liu SD, Mou XL, Qiu YW. Acceleration of denitrification in turbid rivers due to denitrification occurring on suspended sediment in oxic waters. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:4053–4061. doi: 10.1021/es304504m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia ZM, Liu T, Xia XH, Xia N. Effect of particle size and composition of suspended sediment on denitrification in river water. Sci.Total Environ. 2016;541:934–940. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia XH, Jia ZM, Liu T, Zhang SB, Zhang LE. Coupled nitrification-denitrification caused by suspended sediment (SPS) in rivers: importance of SPS size and composition. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;51:212–221. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.6b03886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cai, Y. H. The diversity of marine phytoplankton in Hangzhou Bay [D] (Ocean University of China, 2006).

- 49.AQSIQ,. The specification for oceanographic surve—Part 4: Survey of chemical parameters in the seawater (GB 12763.4-2007). General administration of quality supervision, inspection and quarantine of the People’s Republic of China (2007).

- 50.Caporaso JG, et al. Global patterns of 16 S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bokulich NA, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nature Methods. 2013;10:57–59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2194–2200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schloss PD, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Amann, R. I. Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual (eds. Akkerman, A.D.C., van Elsas, J.D. & de Bruijn, F.J.) 1–15 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995).

- 58.Hammer Ø, Harper DA, Ryan PD. Past:paleontological statistics software package for educationand data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica. 2001;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lepš, J. & Šmilauer, P. Multivariate Analysis of Ecological Data Using CANOCO 224–235 (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.