Abstract

The rolB plant oncogene of Agrobacterium rhizogenes perturbs many biochemical processes in transformed plant cells, thereby causing their neoplastic reprogramming. The oncogene renders the cells more tolerant to environmental stresses and herbicides and inhibits ROS elevation and programmed cell death. In the present work, we performed a proteomic analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana rolB-expressing callus line AtB-2, which represents a line with moderate expression of the oncogene. Our results show that under these conditions rolB greatly perturbs the expression of some chaperone-type proteins such as heat-shock proteins and cyclophilins. Heat-shock proteins of the DnaK subfamily were overexpressed in rolB-transformed calli, whereas the abundance of cyclophilins, members of the closely related single-domain cyclophilin family was decreased. Real-time PCR analysis of corresponding genes confirmed the reliability of proteomics data because gene expression correlated well with the expression of proteins. Bioinformatics analysis indicates that rolB can potentially affect several levels of signaling protein modules, including effector-triggered immunity (via the RPM1-RPS2 signaling module), the miRNA processing machinery, auxin and cytokinin signaling, the calcium signaling system and secondary metabolism.

Introduction

Decades-long study of plant-Agrobacterium interactions and T-DNA oncogene function has revealed very complex behavior of these systems and a sophisticated mechanism of pathogenesis. The rolB oncogene of Agrobacterium rhizogenes is the gene associated with the largest number of disputes and conflicting opinions. Since 1991, it has gradually become apparent that rolB perturbs hormonal signaling pathways in transformed plants and plant cells1,2. RolB alters leaf and flower morphology, provokes heterostyly and the formation of adventitious roots in plant explants3, disturbs root geotropism4 and substantially increases the sensitivity of roots to auxin1,5. The rolB gene promotes de novo meristem formation in tobacco thin cell layers and plants6,7, and the type of organ that is formed from these meristems depends on many factors. The reproductive fate of the ovule and the process of anther dehiscence are also greatly affected in rolB-transformed plants2,7,8. Later, it was found that rolB influences ROS signaling and represses apoptosis in transformed calli9,10. These traits are associated with extremely high resistance of rolB-transformed callus cells to the ROS-inducing herbicides paraquat and menadione9. In general, rolB represses growth, and high expression of the gene causes cell necrosis3. However, cells transformed with moderately or weakly expressed rolB genes acquire a remarkable ability to resist various types of stress factors11 and display enhanced defense against pathogenic fungi12. The activation of secondary metabolism in rolB-transformed calli and plants is a known characteristic of rolB-transformed callus and plant cells, which reflects the general defensive status of the cells and appears to be most likely due to the activation of genes encoding the MYB and bHLH transcription factors13–15.

The first indication that a plant T-DNA oncoprotein might act as a chaperone was published in 200716. The 6b gene of A. tumefaciens belongs to the plast (RolB) gene family17. It was shown that the 6b oncoprotein binds to histone H3 and causes modification of transcription patterns in the host nuclei by changing the epigenetic status of the host chromatin16–18. By affecting chromatin structure, the histone chaperone activity of 6b regulates the expression of genes related to auxin and cytokinin biosynthesis18. In principle, histone modification is a widely known epigenetic alteration that occurs during animal and human oncogenesis19. Other chaperones, such as heat-shock proteins and cyclophilins, have been studied intensively for a long time to show their pivotal role in the processes of oncogenesis in human cells20,21.

Plants generate unorganized cell masses, such as callus or tumors, in response to stresses, such as wounding or pathogen infection22. This experimental system has been used extensively in basic research to address question how plants perceive and transduce endogenous and environmental signals and how they induce or maintain cell differentiation/dedifferentiation22. Presently, callus cultures are widely used in proteomic experiments as a universal model, giving a relatively standardized and homogeneous basis for research. Plant callus cultures were successfully used in proteomics experiments to study the molecular mechanisms underlying different aspects of cell differentiation and somatic embryogenesis23–25, stress adaptation26, and Agrobacterium-plant interaction27.

In this study, we used proteomics analysis in order to identify proteins with different expression in transformed calli. Transformed by the rolB gene calli are primary tumors, which can further differentiate in organs2,6. Taking into account that in rolB-transformed plants, the rolB signaling is interfered with the tissue-specific and developmental signaling2,7,8, we focused on studying primary tumors to see the first layer of regulation devoid of developmental signals. For this, we used moderately rolB-expressing Arabidopsis thaliana calli to find proteins whose abundance was significantly affected by the transformation. The term “moderately expressed” was initially introduced on the model of Rubia cordifolia28 and then applied to Arabidopsis9. The attribution to the average, weak or strong levels of rolB-gene expression was made based on a scale developed earlier28. According to this scale, the average expression of the gene is within 0.3–1.0 relative expression level units (that corresponds to expression of rolB in rolABC- or wild-type pRiA4-transformed cells). We use such callus line where the oncogene was expressed at physiological conditions. In this case, no signs of cell death or necrosis were observed. The culture grew well and the biomass accumulation was almost equal to the control vector-transformed culture. In other words, we created normal physiological conditions for tissues that express the oncogene.

Proteomics analysis showed that rolB perturbs the expression of chaperone-type proteins. In particular, heat-shock proteins of the DnaK subfamily were overexpressed in rolB-transformed calli, whereas the abundance of cyclophilins, members of the closely related single-domain cyclophilin family, decreased.

Experimental Procedures

Plant Material

Arabidopsis thaliana Columbia (Col-0) vector control and rolB-transgenic callus cultures were obtained from seedlings using the pPCV002-CaMVBT construct as described previously9. The calli were cultivated in W2,4-D medium supplemented with 0.4 mg l−1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid in the dark at 24 °C with 30-day subculture intervals. Samples were taken from 21-day cultures designated as “At” (A. thaliana vector control) and “AtB-2” (A. thaliana rolB-transformed calli). These cultures were two years of age. Three biological experiments were carried out.

2-D Gel Electrophoresis and quantification of protein expression

Proteins were isolated from 0.5 g fresh weight of calli using a phenol extraction methanol/ammonium acetate precipitation method29. The phenolic phase was collected and precipitated overnight in five volumes of 100 mM ammonium acetate in ethanol at −20 °C. After centrifugation (10 min, 6000 g, 4 °C), the pellet was washed twice with ice-cold acetone.

For isoelectric focusing, dried protein pellets were dissolved in IPG buffer (9.5 M urea, 4% w/v CHAPS, 2% Pharmalyte pH 3–10 (GE Healthcare, Uppsala, Sweden), DeStreak Reagent (GE Healthcare) and 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue). Protein concentration was determined using an RC/DC kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). A total of 500 µg of whole protein sample in 350 ml IPG buffer was applied to 18-cm Immobiline DryStrip pH 3–10 NL (GE Healthcare) by passive rehydration for 12 h at 20 °C according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. IEF was performed in a Protean IEF Cell (Bio-Rad) for 60,000 V-h. Before separation in the second dimension, the Immobiline DryStrip was equilibrated in buffer (6 M urea, 0.375 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 2% DTT) for 10 min. For SDS-PAGE, 12% polyacrylamide gels with 4% stacking gels were run in a Protean II xi cell (Bio-Rad). The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250. Three control and three experimental gels were used in the analysis.

Protein Expression

Gels were scanned using the PharosFX Plus System (Bio-Rad). PDQuest 8.0.1 Advanced software (Bio-Rad) was used for image and analysis of protein maps. The Spot Detection Wizard was used to select the parameters for spot detection, such as a faint spot and a large spot cluster. The results of automated spot detection were checked and manually corrected. On average, 1,500 protein spots were detected on gels of Arabidopsis calli. A local regression model (Loess) was used for normalization of spot intensity. The protein expression was accessed using PDQuest 8.0.1 Advanced software and was presented as mean total intensity of a defined spot in a replicate gel group. Spot quantity is the sum of the intensities of pixels inside the boundary. Fold of protein expression change was accessed based on mean protein intensity. For quantitative differentiation, a 1.5-fold change or higher in the average spot intensity was regarded as significant. Statistical significance of differences was assessed using Student’s t test at a significance level of 0.05 in three replicates. All identified proteins in qualitatively different spots were considered. Mean expression values and standard deviations were calculated from three biological experiments.

Mass spectrometry

The total number of samples analyzed by MALDI was 203. The number of technical replicates was 2–3 (up to 8 for important proteins). Individual protein spots selected on the basis of image-analysis output were excised and digested in-gel with trypsin (Trypsin V511, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) as previously described30. For MALDI-TOF identification, 0.5–1 μl of the sample (50% solution of acetonitrile in water, 0.1% TFA) was placed on a ground steel MALDI target plate or AnchorChip or SmallAnchor (depending on the protein quantity; also see Supplementary Dataset S1), and 0.5–1 μl of the matrix (α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid) was added. For LC-ESI-MS/MS, 10-μl protein samples dissolved in water containing 0.1% TFA were used.

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry and Protein Identification

All mass spectra were acquired with an Autoflex (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer with a nitrogen laser operated in the positive reflector mode (standard method RP 700–3500 Da.par) under the control of FlexControl software (version 3.4; Bruker Daltonics). The analysis was performed in the automatic mode (AutoXecute – automatic Run). The spectra were externally calibrated using the CalibratePeptideStandards.FAMSMethod and a standard calibration mixture (Protein Calibration Standard I, Bruker Daltonics). The data files were transferred to Flexanalysis software version 3.4 (Bruker Daltonics) for automated peak extraction. Assignment of the first monoisotopic signals in the spectra was performed automatically using the signal detection algorithm SNAP (Bruker Daltonics). For MS and MS/MS analyses, we used the PMF.FAMSMethod and SNAP_full_process.FALIFTMethod, respectively. Each spectrum was obtained by averaging 1500–5000 laser shots (300 shots in a step) acquired at the minimum laser power. The data were analyzed using BioTools (version 3.2; Bruker Daltonics). A peptide mass tolerance of 0.5 Da and a fragment mass tolerance of 0.5 Da were adopted for database searches. The m/z spectra were searched against the Arabidopsis thaliana NCBInr and SwissProt databases using the Mascot search engine. Threshold score was 40. Further data were analyzed using UniProt (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/) and other specialized databases and programs as indicated below. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE31 partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD005889 (DOI: 10.6019/PXD005889).

LC-ESI-MS/MS

For determination of proteins of low abundance, we used (in additional to MALDI analysis) an HCTultra PTM Discovery System (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Germany) equipped with a Proxeon EASY-nLC ultra-performance liquid chromatograph and a nanoFlow ESI sprayer. The coupling of Proxeon EASY-nLC to the Bruker HCT ion trap was performed using the program HyStar v3.2 (Bruker Daltonik GmbH). The HCTultra is equipped with a high-capacity ion trap that enables the acquisition of MS/MS data on low-abundance precursor ions. For the LC studies, Buffer A (0.1% formic acid in water) and Buffer B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile/10% water) (Acetonitrile G Chromasolv for HPLC, super gradient grade; Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) were used. Separation was carried out on a C18-reversed phase EASY-Column (10 cm × 75 µm i.d., 3-µm beads, 120-Å pore size, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The flow rate was 300 nl min−1 with the following gradient: 5% Buffer B at 0 min, linearly increased to 35% B at 10 min and to 100% B from 10 to 25 min followed by washing at 100% B from 25 to 40 min. The ion trap capillary temperature was set to 300 °C, and the dry gas flow was 5 l min−1. The ion trap was set to acquire in positive ion mode, scanning in the manufacturer-specified standard enhanced mode (8,100 m/z/s) between m/z 300 and 2,000 for MS, averaging five spectra, and accumulated 200,000 charges (by ion charge control). Collision-induced dissociation fragmentation was performed on the four most intense ions with the threshold for precursor ion selection at an absolute intensity of 20,000. The strict active exclusion was used; a precursor ion was excluded after one spectrum and released after 0.1 min. MS-MS spectra were scanned from m/z 300–2,000, averaging three spectra. Data were analyzed using BioTools (version 3.2; Bruker Daltonics). The following parameters were used for database searches: peptide mass tolerance 0.1% and fragment mass tolerance 0.5 Da.

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time PCR

The isolation of total RNA and first-strand cDNA synthesis were carried out as described previously9. RNA samples were isolated from callus cultures during the linear phase of growth (20–22 days). RNA concentration and 28S/18S ratios were determined using an RNA StdSens LabChip® kit and ExperionTM Automated Electrophoresis Station (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) with ExperionTM Software System Operation and Data Analysis Tools (version 3.0) following the manufacturer’s protocol and recommendations. The samples with 28S/18S ribosomal RNA between 1.5–2.0 and an RNA Quality Indicator (RQI) above 9.0 were used for real-time PCR analysis. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analysis was performed using a CFX96 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) with 2.5 × SYBR green PCR master mix containing ROX as a passive reference dye (Syntol, Russia) as described9. Two biological replicates, resulting from two different RNA extractions, were used for analysis, and three technical replicates were analysed for each biological replicate. The gene-specific primer pairs used in the qPCR were as follows in the Supplementary Table S1. A. thaliana actin (AtAct2) and ubiquitin (AtUBQ10) genes (GenBank ac. no. NM_112764 and NM_001084884, respectively) were used as endogenous controls to normalize variance in the quality and the amount of cDNA used in each real-time RT-PCR experiment9. The highest expressing sample assigned the value 1 in the relative mRNA calculation using the formula 2−ΔΔCT. Data were analyzed using CFX Manager Software (Version 1.5; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). For comparison among multiple data, analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a multiple comparison procedure was employed. Fisher’s protected least significant difference (PLSD) post-hoc test was employed for the inter-group comparison. A difference of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Protein Network Visualization

The network was built using the program Cytoscape as previously described32. The data loaded into the program were obtained from the PAIR [PAIR-V3.333, http://www.cls.zju.edu.cn/pair/]. The protein-protein interactions presented in PAIR were compared with the databases BioGRID34 (http://thebiogrid.org/). The size of each circle is correlated with the “betweenness centrality” metric, which describes the global position (“centrality”) of the protein in the interactome. Betweenness centrality was calculated by Cytoscape. Information about protein-protein interactions was also obtained by using UniProt and by linking Cytoscape with external databases (IntAct and STRING). The network was validated using recently developed algorithms35,36.

Data Availability

The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to ProteomeXchange via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD005889 (Project DOI: 10.6019/PXD005889).

Results

Characterization of the rolB-expressing line AtB-2

Expression of rolB in AtB-2 callus line was tested by qPCR before proteomic analysis. The rolB-expressing callus line AtB-2 was shown to be a line with moderate rolB expression (0.56 ± 0.04 relative expression level units, see Supplementary Table 2). The presence of the RolB protein in callus extracts was confirmed by mass spectrometry (Supplementary Dataset S3).

Proteomics Analysis

Total protein fractions were isolated from Arabidopsis thaliana vector control and rolB-transgenic callus cultures as described in Materials and Methods. Overall, 1,500 proteins were resolved on 2-D gels (Supplementary Figure S1). Of these, over 200 were identified using MALDI MS. Proteins whose determinations represented reliable data meeting the requirements of precision mass-spectrometric analysis and quantitative differences for proteins are included in Tables 1 and 2 and were considered in further analysis (see also Supplementary Dataset S1 and Dataset S2). Three differentially expressed proteins remain undetermined because the search of databases yielded no results. Thus, 31 proteins were upregulated in rolB-expressing cells compared with control cells (Table 1), and 29 proteins were down-regulated (Table 2). We also performed a targeted search of chaperone-type proteins using their predicted masses and isoelectric points. These data are presented in Table 3. To identify low-abundance proteins such as VH1-interacting kinase and heat stress tolerant DWD1 (DWD1/HTD1), we used an Anchor chip or SmallAnchor chip (otherwise, it was not possible to identify these proteins). Examples are shown in Supplementary Dataset S1. RolB itself was also detected (Supplementary Dataset S3).

Table 1.

Proteins upregulated in rolB-expressing Arabidopsis calli.

| UniProtKB code | Name of the protein | Function or biological process | Activation, folds* | Notes1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Q9SN86 (MDHP_ARATH) | Malate dehydrogenase, chloroplastic/MDH | Carbohydrate metabolic process Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

14 ± 2 | Primary metabolism Response to cold |

| 2 | Q9LDV4 (ALAT2_ARATH) | Alanine aminotransferase 2, mitochondrial | Synthesizes pyruvate from L-alanine Photosynthesis |

12 ± 2 | Primary metabolism Response to hypoxia |

| 3 | Q9LVW7 (CARA_ARATH) | Carbamoyl-phosphate synthase small chain, chloroplastic | Amino-acid biosynthesis | 10 ± 0.5 | Primary metabolism Response to phosphate starvation |

| 4 | Q9LZ66 (SIR_ARATH) | Assimilatory sulfite reductase (ferredoxin), chloroplastic | Assimilatory sulfate reduction pathway during both primary and secondary metabolism | 10 ± 2 | Secondary metabolism Response to cold |

| 5 | Q9S7B5 (THRC1_ARATH) | Threonine synthase 1, chloroplastic | L-threonine biosynthesis | 1 ± 0.5 | Primary metabolism Stress-inducible1 |

| 6 | P24102 (PER22_ARATH) | Peroxidase 22 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 5.6 ± 0.7 | Plant defense |

| 7 | Q9SJZ2 (PER17_ARATH) | Peroxidase 17 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 3.4 ± 0.6 | Plant defense |

| 8 | Q9C6Z3 (ODPB2_ARATH) | Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta-2, chloroplastic | Fatty acid biosynthetic process Glycolysis |

5.3 ± 0.7 | Primary metabolism |

| 9 | Q9LFG2 (DAPF_ARATH) | Diaminopimelate epimerase, chloroplastic | Amino-acid biosynthesis | 4 ± 1.5 | Primary metabolism Stress-inducible1 |

| 10 | Q9SRY5 (GSTF7_ARATH) | Glutathione S-transferase F7 | Defense response to bacterium Defense response to fungus, incompatible interaction Response to salt stress |

3.5 ± 0.4 | Plant defense |

| 11 | P42760 (GSTF6_ARATH) | Glutathione S-transferase F6 | Defense response to bacterium Response to oxidative stress Response to salt stress Response to water deprivation |

3.5 ± 0.6 | Plant defense Involved in camalexin biosynthesis |

| 12 | Q9FUS6 (GSTUD_ARATH) | Glutathione S-transferase U13 | Detoxification Stress response |

3 ± 0.2 | Plant defense |

| 13 | Q9FWR4 (DHAR1_ARATH) | Glutathione S-transferase DHAR1, mitochondrial | Scavenging of ROS under oxidative stresses | 2 ± 0.3 | Plant defense Key component of the ascorbate recycling system |

| 14 | Q9STW6 (HSP7F_ARATH) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 6, chloroplastic/Hsp70-6 Synonym: cpHsc70-1 |

Host-virus interaction, protein transport, stress response | 2.4 ± 0.15 | Chaperone |

| 15 | Q9LTX9 (HSP7G_ARATH) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 7, chloroplastic/Hsp70-7 | Host-virus interaction, protein transport, stress response | 2.9 ± 0.6 | Chaperone |

| 16 | Q9SIF2 (HS905_ARATH) | Heat shock protein 90-5, chloroplastic Hsp90-5/CR88 Synonym: Hsp88.1 |

Response to heat Response to salt stress Response to water deprivation Embryo development |

2.4 ± 0.7 | Chaperone |

| 17 | P21238 (CPNA1_ARATH) | Chaperonin 60 subunit alpha 1, chloroplastic, Cpn60 | Chloroplast organization Embryo development |

2.3 ± 0.6 | Chaperone |

| 18 | O65282 (CH20_ARATH) | 20 kDa chaperonin, chloroplastic, Cpn10 | Stress response Required to activate the iron superoxide dismutases (FeSOD) |

2 ± 0.6 | Chaperone Functions along with Cpn60 |

| 19 | O04130 (SERA2_ARATH) | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase 2, chloroplastic | Amino-acid biosynthesis | 2.5 ± 1 | Primary metabolism |

| 20 | Q9M9K1 (PMG2_ARATH) | 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase 2 | Glycolysis | 2.1 ± 0.5 | Primary metabolism |

| 21 | Q42592 (APXS_ARATH) | L-ascorbate peroxidase S, chloroplastic/mitochondrial | Plays a key role in hydrogen peroxide removal | 2 ± 0.5 | Plant defense |

| 22 | Q9XI87 (Q9XI87_ARATH) | VH1-interacting kinase (VIK) |

Auxin-activated signaling pathway, negative regulation of programmed cell death, plant-type hypersensitive response, response to cold and water deprivation | 2 ± 0.6 | Signal transduction, MAPK cascade |

| 23 | Q9ZUN8 (Q9ZUN8_ARATH) | HEAT STRESS TOLERANT, DWD1 Synonym: HTD1/WD-40 repeat family protein |

Cul4-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase complexHeat stress response | 2 ± 0.4 | Signal transduction |

| 24 | Q9S7D8 (APS4_ARATH) | ATP sulfurylase 4, chloroplastic/APS4 | Hydrogen sulfide biosynthetic process Regulation of hypersensitive response |

2.2 ± 1.0 | Positive regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis |

| 25 | Q9SA34 (IMDH2_ARATH) | Inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | Purine biosynthesis | 2.1 ± 1.0 | Primary metabolism |

| 26 | P93819 (MDHC1_ARATH) | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic 1 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 2 ± 0.6 | Primary metabolism Stress-inducible1 |

| 27 | P57106 (MDHC2_ARATH) | Malate dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic 2 | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 2 ± 0.7 | Primary metabolism Stress-inducible1 |

| 28 | Q94JQ3 (GLYP3_ARATH) | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase 3, chloroplastic | Glycine metabolic process | 2 ± 0.2 | Primary metabolism |

| 29 | O22832 (STAD7_ARATH) | Acyl-[acyl-carrier-protein] desaturase 7, chloroplastic, FAB2 | Fatty acid biosynthetic process | 2 ± 0.3 | Plant defense |

| 30 | P41088 (CFI1_ARATH) | Chalcone-flavonone isomerase 1/TRANSPARENT TESTA 5 | Flavonoid biosynthesis | 2 ± 0.15 | Secondary metabolism |

| 31 | Q8VY84 (KCY1_ARATH) | Probable UMP-CMP kinase 1 | Pyrimidine nucleotide biosynthetic process | 1.8 ± 0.12 | Primary metabolism |

1Data from UniProt and TAIR.

2Less and Galili59.

*Mean ± standard deviation of three biological repeats.

Table 2.

Proteins down-regulated in rolB-expressing Arabidopsis calli.

| UniProtKB code | Name of the protein | Function or biological process1 | Inhibition, folds | Notes1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Q9M885 (RS72_ARATH) | 40S ribosomal protein S7-2 | Structural constituent of ribosome | 15 ± 4 | Protein biosynthesis |

| 2 | Q9C514 (RS71_ARATH) | 40S ribosomal protein S7-1 | Structural constituent of ribosome | 12 ± 2 | Protein biosynthesis |

| 3 | P57720 (AROC_ARATH) | Chorismate synthase, chloroplastic | Catalyzes the last common step of the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids, produced via the shikimic acid pathway | 11 ± 2 | Aromatic amino acid biosynthesis |

| 4 | Q38867 (CP19C_ARATH) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP19-3/Rotamase cyclophilin-2, ROC2 | Protein folding | 10 ± 0.5 | Chaperone Signal transduction |

| 5 | P34791 (CP20C_ARATH) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP20-3/Rotamase cyclophilin-4, ROC4 | Protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization Links light and redox signals |

10 ± 1 | Chaperone |

| 6 | P34790 (CP18C_ARATH) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP18-3, ROC1 | Protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization Plant defense Hypersensitive response |

6.6 ± 0.7 | Chaperone |

| 7 | Q9SKQ0 (CP19B_ARATH) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP19-2/ROC6 | Protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization | 6.0 ± 0.4 | Chaperone |

| 8 | Q9ASS6 (PNSL5_ARATH) | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase CYP20-2 | Protein peptidyl-prolyl isomerization NAD(P)H dehydrogenase complex assembly |

3.4 ± 0.4 | Chaperone Modulates the conformation of BZR1 |

| 9 | Q96255 (SERB1_ARATH) | Phosphoserine aminotransferase 1, chloroplastic | Amino-acid biosynthesis | 8.9 ± 1.0 | Primary metabolism |

| 10 | Q93ZC5 (AOC4_ARATH) | Allene oxide cyclase 4, chloroplastic | Jasmonic acid biosynthetic process | 5.4 ± 0.5 | |

| 11 | O49485 (SERA1_ARATH) | D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase 1, chloroplastic | L-serine biosynthetic process Embryo development Pollen development |

2.6 ± 0.5 | Primary metabolism |

| 12 | Q8RWV0 (TKTC1_ARATH) | Transketolase-1, chloroplastic | Pentose-phosphate cycle | 2.8 ± 0.3 | Primary metabolism |

| 13 | Q9C5Y9 (Q9C5Y9_ARATH) | Initiation factor 3 g | Stimulates binding of mRNA and methionyl-tRNAi to the 40S ribosome | 2.6 ± 0.2 | Protein biosynthesis |

| 14 | Q8LFK2 (Q8LFK2_ARATH) | Adenine nucleotide alpha hydrolases-like protein | Hydrolase activity | 2.7 ± 0.2 | Response to stress |

| 15 | Q9FMF5 (RPT3_ARATH) | Root phototropism protein 3, RPT3 | Substrate-specific adapter of an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase complex (CUL3-RBX1-BTB) | 2.2 ± 0.5 | Signal transduction |

| 16 | O49203 (NDK3_ARATH) | Nucleoside diphosphate kinase III, chloroplastic/mitochondrial | Nucleoside triphosphate biosynthetic process | 2.1 ± 0.5 | Nucleotide metabolism |

| 17 | O04310 (JAL34_ARATH) | Jacalin-related lectin 34 | Copper ion binding Response to cold |

2.1 ± 0.5 | Brassinosteroid biosynthetic process |

| 18 | Q8LBZ7 (SDHB1_ARATH) | Succinate dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] iron-sulfur subunit 1, mitochondrial | Tricarboxylic acid cycle | 2.1 ± 0.2 | Primary metabolism |

| 19 | Q8W4S6 (INV6_ARATH) | Beta-fructofuranosidase, insoluble isoenzyme CWINV6 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 2 ± 0.15 | Primary metabolism |

| 20 | F4JGR5 (PFPB2_ARATH) | Pyrophosphate-fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase subunit beta 2 | Glycolysis | 2 ± 0.6 | Primary metabolism |

| 21 | Q9LZT4 (EXLA1_ARATH) | Expansin-like A1 | Plant-type cell wall loosening, unidimensional cell growth | 2 ± 1 | |

| 22 | O80713 (SDR3A_ARATH) | Short-chain dehydrogenase reductase 3a | Hypersensitive response | 2 ± 0.2 | Plant defense |

| 23 | Q9ZV34 (Q9ZV34_ARATH) | Pathogenesis-related thaumatin-like protein | Unknown | 2 ± 1 | Probably a defensive function |

| 24 | Q9LK23 (G6PD5_ARATH) | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, cytoplasmic isoform 1 | Pentose-phosphate cycle | 1.8 ± 0.4 | Primary metabolism |

| 25 | P32962 (NRL2_ARATH) | Nitrilase 2 | Indoleacetic acid biosynthetic process | 1.8 ± 0.3 | |

| 26 | Q9XEE2 (ANXD2_ARATH) | Annexin D2 | Calcium-dependent phospholipid binding Response to stress |

1.5 ± 0.2 | Polysaccharide transport |

| 27 | Q9SR13 (FLK_ARATH) | Flowering locus K homology domain | RNA binding | 1.5 ± 0.3 | Positive regulation of flower development |

| 28 | O24456 (GBLPA_ARATH) | Receptor for activated C kinase 1 A, RACK1A | MAP-kinase scaffold activity Protein complex scaffold Signal transducer activity |

1.5 ± 0.2 | Signal transduction |

| 29 | Q9FWA3 (6GPD3_ARATH) | 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, decarboxylating 3 | Pentose phosphate pathway | 1.5 ± 0.2 | Primary metabolism |

1Data from UniProt and TAIR.

Table 3.

Chaperone-type proteins which abundance was not changed in rolB-expressing calli.

| UniProtKB code | Name of the protein | Function or biological process | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Q9LDZ0 (HSP7J_ARATH) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 10, mitochondrial (Hsp70-10) | Response to heat Response to salt stress Response to virus | Chaperone |

| 2 | Q9S7C0 (HSP7O_ARATH) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 14, cytoplasmic and nucleolar (Hsp70-14) | Response to heat | Chaperone |

| 3 | F4HQD4 (HSP7P_ARATH) | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 15 cytoplasmic and nucleolar (Hsp70-15) | Response to stress | Chaperone |

| 4 | P55737 (HS902_ARATH) | Heat shock protein 90-2, cytoplasmic (Hsp90-2) Synonym: Hsp81-2 |

Response to stress Defense response to bacterium |

Chaperone Maintains appropriate levels of immune receptor proteins to avoid autoimmunity |

| 5 | Q9LV21 (TCPD_ARATH) | TCP-1/cpn60 chaperonin family protein, cytoplasmic (T-complex protein 1 subunit delta) |

Folding of actin and tubulin | Chaperone |

Proteins Upregulated in rolB-expressing Cells

Primary metabolism and ROS-detoxifying enzymes

Several proteins involved in various biosynthetic processes of primary metabolism were strongly activated; these included alanine aminotransferase, carbamoyl phosphate synthase, malate dehydrogenase, threonine synthase, pyruvate dehydrogenase and others (Table 1). Another subset of upregulated proteins was represented by defensive enzymes involved in ROS metabolism. Among them were peroxidases, the activation of which in rolB-expressing cells was previously demonstrated at the level of gene expression37. The increase in expression of antioxidant enzymes determined in the present work was essentially the same as determined previously by other methods38, thus confirming the reliability of the proteomics experiments. The previously found induction of ascorbate peroxidase genes in rolB-transformed cells9 was also confirmed (Table 1). New data were obtained regarding glutathione S-transferases. Glutathione S-transferases F6 and F7, as well as glutathione S-transferase DHAR1, a key component of the ascorbate recycling system39, were upregulated in rolB-transformed cells. These transferases are involved in redox homeostasis and especially in the scavenging of ROS under oxidative stress conditions subsequent to induction by biotic or abiotic inducers39. Taken together, our data confirm the hypothesis9 that rolB affects ROS metabolism by participating in a cellular process that resembles the process of stress acclimation.

Heat-shock proteins and chaperonins

Heat-shock 70-kDa proteins 6 and 7 (Hsp70-6 and Hsp70-7), Hsp90-5, 20-kDa chaperonin (Cpn10) and chaperonin 60 subunit α1 were activated in rolB-expressing Arabidopsis cells (Table 1). It is known that in cooperation with other chaperones, Hsp70s stabilize preexisting proteins against aggregation and mediate the folding of newly translated polypeptides in the cytosol as well as within organelles40. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing a fungal hsp70 gene exhibited enhanced tolerance to heat stress and to osmotic, salt and oxidative stresses40.

The Hsp70 protein family is divided into two subfamilies: DnaK and Hsp110/SSE41. Of the DnaK subfamily, only chloroplastic AtHsp70-6 and AtHsp70-7 were upregulated in rolB-transformed cells. Other Hsp70 proteins found by the targeted analysis, such as AtHsp70-10 (DnaK subfamily, mitochondrial) and AtHsp70-14 and AtHsp70-15 (Hsp110/SSE subfamily, cytosolic), were found in equal abundance in control and rolB-expressing calli (Table 3).

Other proteins

The abundance of the VH1-interacting kinase (VIK, VH1-interacting tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-containing protein) in rolB-transformed cells was also increased. Another protein upregulated in the transformed cells was DWD1/HTD1. This protein was shown to participate in heat stress responses, possibly by interacting with Hsp90-142. Enzymes that participate in secondary metabolism, such as chalcone-flavonone isomerase 1 and ATP sulfurylase 4, were upregulated.

Proteins Down-Regulated in rolB-expressing Cells

Expression of the 40S ribosomal proteins S7-2 and S7-1 was significantly inhibited in rolB-expressing cells (Table 2). These proteins are structural constituents of the ribosome and participate in ribosomal RNA processing, ribosomal small subunit biogenesis and translation (BioGrid). Initiation factor 3 g was also down-regulated. This factor is involved in protein synthesis; together with other initiation factors, it stimulates binding of mRNA and methionyl-tRNAi to the 40S ribosome. These data indicate that rolB can potentially inhibit protein biosynthesis.

The expression of several enzymes involved in processes of primary metabolism such as glycolysis, the pentose phosphate cycle, amino acid biosynthesis, carbohydrate metabolic processes, the Calvin cycle and the Krebs cycle was moderately inhibited. Among them were chorismate synthase, phosphoserine aminotransferase 1, D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase 1, transketolase 1, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase, pyrophosphate-fructose 6-phosphate 1-phosphotransferase and others (Table 2). The suppression of these enzymes reflects the repressive action of rolB on primary metabolism that eventually causes the well-known growth-inhibiting effect of rolB.

Several peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerases were down-regulated in rolB-transformed cells. This group of proteins, also called cyclophilins or immunophilins, has been shown to possess peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPIase) activity that is involved in protein folding. It includes CYP18-3 (ROC1), CYP19-2 (ROC6), CYP19-3 (ROC2), CYP20-2 and CYP20-3 (ROC4). RolB affects only one family of closely related single-domain cyclophilins (Clade I)43 (Table 2). The receptor for activated C kinase 1 A (RACK1A) was down-regulated in rolB-transformed cells (Table 2). RACK1A, a WD-40-type scaffold protein, is the major RACK1 regulatory protein conserved in eukaryotes. RACK1A participates in multiple signal transduction pathways, including pathways mediated by RACK1A-cyclophilin interactions44,45. Interestingly, some enzymes involved in plant hormone biosynthesis, such as allene oxide cyclase 4 (jasmonic acid biosynthesis), jacalin-related lectin 34 (brassinosteroid biosynthesis) and nitrilase 2 (indoleacetic acid biosynthesis), were down-regulated (Table 2).

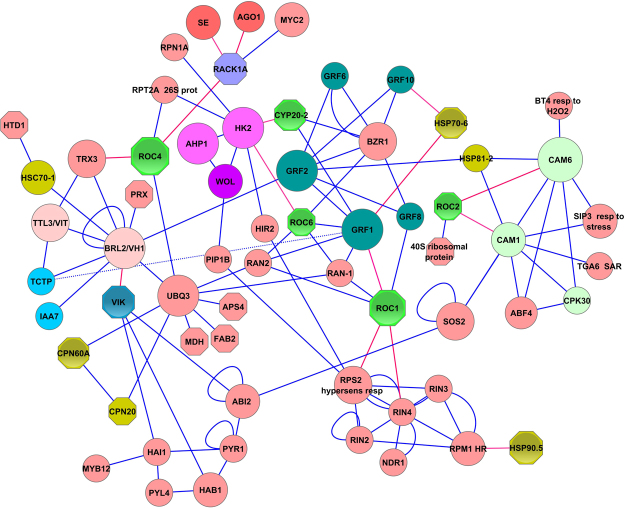

Analysis of Gene Expression

To confirm the results of the proteomic analysis, qPCR was performed to detect expression of genes corresponding to six up-regulated proteins, six down-regulated proteins and five proteins which abundance was not changed in rolB-expressing Arabidopsis calli (Fig. 1). The activation of VIK, Hsp70-6, Hsp70-7, Hsp90-5, Cpn60 and Cpn10 genes in AtB callus culture was consistent with the proteomic data (Table 1, Fig. 1A). Expression of RACK1A, ROC2, ROC4, ROC1, ROC6 and CYP20-2 was decreased in rolB-expressing cells (Fig. 1B). In agreement with the proteomic data, no significant differences were observed in expression levels of the Hsp70-10, Hsp70-14, Hsp70-15, Hsp90-2 and TCP-1 genes in At and AtB calli (Fig. 1C). Thus, the gene-expression data were in accordance with proteomics data.

Figure 1.

Expression of chaperone genes, VIK and RACK1A in Arabidopsis normal and rolB-transformed calli. RNA samples were isolated from callus cultures during the linear phase of growth (20–22 days). qPCR data (mean ± standard error) were summarized from two biological and three technical replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences of means (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01), Fisher’s LSD.

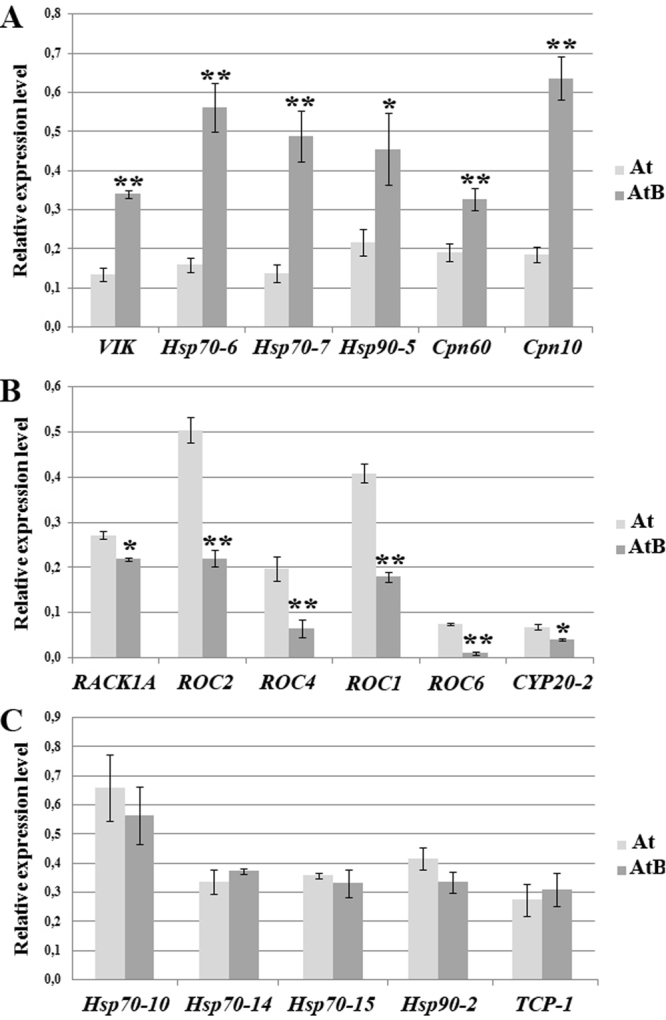

Network Reconstruction and Analysis

To create a subnetwork of signaling components affected by RolB, we used our previous reconstruction of the Arabidopsis interactome32, as well as algorithms for construction of subgraphs and validation of small subnetworks35,36. Our analysis indicated high level of integrity of the subnetwork presented in Fig. 2. Deleting the individual nodes indicated by octagons (affected by RolB) eliminated the subnetwork. Removing nodes that are not directly related to octagons does not destroy the network (in this case, the network turns out to be simpler). As can be seen from Fig. 2, the network shows the perturbations of the proteome but does not show input nodes. Although it is impossible at present to determine the primary targets of the oncoprotein, the reconstruction is useful for creating a working model.

Figure 2.

General presentation of changes in the Arabidopsis protein signaling network caused by expression of the rolB gene. The octahedrons represent proteins whose expression was changed by rolB. Heat shock proteins are shown in brown-green and cyclophilins in bright green. The most important interactions are indicated by red lines. The basic signaling modules are as follows (top to bottom): SE and AGO1 (red nodes) represent members of the miRNA processing machinery (the complete subnetwork is presented in32). The violet circles HK2, AHP1 and WOL represent core components of the cytokinin signaling network. To their right, a large cluster of general regulatory factors (GRFs) is highlighted in green. In the central part of the figure on the left, the hub proteins BRL2/VH1 and TTL3/VIT (brassinosteroid and auxin signaling) and CAMs on the right (calcium signaling) are presented. The RPM1-RPS2 signaling module is located at the bottom right of the figure. The interactions of VIK with the protein phosphatases HAI1, HAB1 and ABI2 indicate possible links of VIK with abscisic acid signaling and chromatin-remodeling complexes82. BZR1, brassinazole-resistant 1; GRFs, growth-regulating factors; HSPs, heat shock preteins; RANs, RAN GTPase-activating proteins; ROCs, rotamase cyclophilins; RACK1A, receptor for activated C kinase 1A; RPT2A, 26S proteasome AAA-ATPase subunit; RPN1A, 26S proteasome regulatory subunit S2 1 A; SE, Serrate; AGO1, Argonaute 1; MYC2, transcription factor MYC2; CYP20-2, CYCLOPHILIN 20-2; HK2, histidine kinase 2; AHP1, histidine-containing phosphotransmitter 1; WOL, histidine kinase 4; PIP1B, aquaporin PIP1-2; TCTP, translationally controlled tumor protein; BRL2/VH1, serine/threonine-protein kinase BRI1-like 2; PRX, PEROXIDASE; TRX3, thioredoxin H3; TTL3/VIT, tetratricopetide-repeat thioredoxin-like 3/VHI-interacting TPR containing protein; HSC70-1, heat shock cognate protein 70-1; HTD1, heat stress tolerant DWD 1; UBQ3, polyubiquitin 3; CPNs, chaperonins; MDH, malate dehydrogenase; FAB2, fatty acid biosynthesis 2; APS4, sulfate adenylyltransferase; VIK, VH1-interacting tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-containing protein; HAI1, highly ABA-induced PP2C; MYB12, transcription factor MYB12; PYL4, abscisic acid receptor PYL4; HAB1, protein phosphatase 2 C 16; ABI2, protein phosphatase 2C 77; PYR1, abscisic acid receptor PYR1; SWI3B, chromatin remodeling complex subunit B; HIR2, hypersensitive-induced response protein 2; RPS2, disease resistance protein RPS2; RINs, E3 ubiquitin protein ligases; RIN4, RPM1 interacting protein 4; NDR1, non-race specific disease resistance protein 1; RPM1, disease resistance protein RPM1; SOS2, CBL-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 24; CAMs, calmodulins; BZIPs, basic leucine-zippers; BZO2H1, basic leucine zipper 10; ABF4, ABA-responsive element binding protein 4; CPK30, calcium-dependent protein kinase 30; BT4, BTB and TAZ domain protein 4; SIP3, CBL-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 6; TGA6, transcription factor TGA6; NPR1, nonexpresser of PR genes 1.

Cyclophilins

ROC1 (CYP18-3): As a first step in the reconstruction of signaling components affected by RolB, we began to reconcile ROC1 interactions (Fig. 2). The abundance of ROC1 in rolB-transformed cells is significantly decreased (Table 2). Via RIN4, ROC1 is connected to the RPM1-RPS2 signaling module46 that controls effector-triggered immunity. Another consequence of ROC1 deficiency might be perturbations in the expression of ROC1-associated proteins such as RAN1 and RAN2 (RAN GTPase-activating proteins, Fig. 2) as well as the 14-3-3 proteins GRF1 and GRF8 (general regulatory factors). RANs mediate protein import into nuclei and the cellular response to salt stress. The interaction of ROC1 with GRFs was demonstrated previously47, but neither the exact mechanism of this interaction nor its outcome is known.

ROC2 (CYP19-3): ROC2 physically interacts with calmodulins (CAMs) and thus affects a broad array of reactions controlled by CAMs48. These include the response to stress (mediated by the CBL-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 6 (SIP3), BTB and TAZ domain protein 4 (BT4) and basic leucine-zipper proteins; Fig. 2) and induced systemic resistance (mediated by TGA6 and NPR1). It is likely that in this manner, i.e., via ROC2-CAM interactions, rolB also exerts its modulating effect on calcium-dependent protein kinases49.

ROC4 (CYP20-3): ROC4 connects redox and light signals to cysteine biosynthesis and stress responses in chloroplasts50 and is known to be a key effector protein that links hormone signaling to amino acid biosynthesis and redox homeostasis during stress responses51. The important interactions of ROC4 include its interaction with the 26S proteasome subunit RPT2A and with RACK1A (Fig. 2). RPT2A controls the meristematic activity in roots and shoots52. Both RPT2A and RACK1A mediate crosstalk between developmental and defense signaling pathways in plants44,45,53,54. Reduction of the concentration of ROC4 in transformed cells should ultimately lead to a change in the immune status of the cells. Unfortunately, the precise mechanism of the ROC4-RPT2A interaction or ROC4-RACK1A interaction is unknown.

RACK1 is a WD-40-type scaffold protein that is conserved in eukaryotes and plays regulatory roles in diverse signal transduction and stress response pathways44. RACK1A ensures the accumulation and processing of some pri-miRNAs, directly interacting with SERRATE and the AGO1 complex55. These interactions explain recent data indicating the active involvement of rolB in the modulation of expression of core components of the miRNA processing machinery, including SERRATE and AGO156.

ROC4 also interacts with TRX3 (thioredoxin)57. TRX3 controls the abundance of numerous proteins that are involved in a wide variety of processes including the Calvin cycle, metabolism, photosynthesis, defense against oxidative stress and amino acid synthesis57. Again, the precise function of the ROC4-TRX3 interaction is unknown (see also the interaction data presented at http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/interaction/EBI-449668;jsessionid=BC14D657B31C0FA84F73F7E9DC43F683). However, because TRX3 has a dual function as a disulfide reductase and a molecular chaperone58, decreased ROC4 abundance could diminish ROC4-TRX3 interactions and thus TRX activity. Indeed, many of the proteins whose expression is increased in rolB-expressing cells (Table 1) are under the control of TRX359. These include ascorbate peroxidases, glutathione S-transferase DHAR, glutathione S-transferase F6, alanine aminotransferase and others.

ROC6 (CYP19-2) and CYP20-2: The cyclophilins ROC6 (CYP19-2) and CYP20-2 interact with the transcriptional repressor BZR1 and the cytokinin signaling system (Fig. 2). The interaction between CYP20-2 and BZR1 is presently considered important in the regulation of flowering60. BZR1 modulates ovule initiation and development by monitoring the expression of genes related to ovule development. The HK2 (histidine kinase 2) cytokinin receptor, together with the histidine-containing phosphotransferase protein AHP1 and the histidine kinase WOL, regulates many developmental processes including meristematic activity, cell division, chlorophyll content, root growth and shoot promotion (TAIR annotation). Reprogrammed reproductive fate of the ovule, decreased chlorophyll content, lateral root growth and shoot promotion are characteristic traits of rolB-transformed plants7,8,61. Therefore, the CYP19-2:CYP20-2–HK2/BZR1 interactions provide evidence in favor of the involvement of rolB in cytokinin signaling and may explain the numerous cytokinin-dependent morphological alterations observed in A. thaliana rolB-transformed plants61.

VH1-interacting kinase (VIK)

Expression of rolB in Arabidopsis calli led to the activation of several regulatory proteins. We found increased expression of the VH1-interacting kinase (VIK) in rolB-transformed cells (Table 1). VIK participates in the regulation of the hub protein VH1/BRL2, facilitating the diversification and amplification of signals perceived by VH1/BRL262. VH1/BRL2, in turn, interacts with TCTP (translationally controlled tumor protein), a general regulator required for the development of the entire plant, and with IAA7 (auxin-responsive protein IAA7), one of the members of the AUX/IAA family of auxin-induced transcriptional regulators. VIK is involved in the auxin-activated signaling pathway, the defense response to fungi, the negative regulation of programmed cell death, regulation of the plant-type hypersensitive response and responses to cold and water deprivation (TAIR annotation). Many of these responses have previously been shown to occur in rolB-expressing cells. RolB perturbs the auxin signaling pathway1, activates the defense response to fungi12, negatively regulates programmed cell death10, ensures higher resistance to salinity, cold and water deprivation11 and causes symptoms that closely resemble systemic acquired acclimation9. However, we could not find a relationship between VIK and cyclophilins either in our reconstructions or the literature.

Auxins and cytokinin signaling

It is generally accepted that rolB-induced modification of hormone signaling causes developmental abnormalities in transformed plants. The interaction of rolB with the protein module VIK-VH1/BRL2-(TCTP; IAA7) (Fig. 2) offers a plausible explanation of the mechanism by which rolB modulates auxin signaling. TCTP is a central mediator of auxin homeostasis and root development63; modification of its activity might be essential for the manifestation of many rolB-induced traits. Moreover, the function of TCTP in regulating cell division is part of a conserved growth regulatory pathway that is shared by plants and animals64, further confirming the idea that plant oncogenes affect ancient regulatory mechanisms. TCTP interacts with GRF1; modulation of its activity by rolB might also occur more directly via ROC1-GRF1-TCTP interaction (Fig. 2). IAA7 is connected with the expanded auxin subnetwork (27 proteins; the complete auxin network is presented in ref.32). IAA7 mediates not only the response to auxin but also gravitropism. Lessening of gravitropism is a well-known effect of rolB4.

It is clear that modification of auxin signaling in rolB-expressing cells is closely connected to the modification of cytokinin signaling. One pathway by which rolB might affect cytokinin signaling involves the interaction of ROC6 and CYP20-2 with HK2. This interaction affects the central cytokinin signaling module HK2-AHP1-WOL (indicated by the violet circles in Fig. 2). Thus, promising interactions for further investigation of the modification of auxin/cytokinin pathways in rolB-transformed cells include VIK-VH1/BRL2-(TCTP; IAA7), ROC1-GRF1-TCTP and ROC6;CYP20-2–HK2. It is very likely that auxin signaling is affected by cyclophilins in rolB-transformed cells; recent studies have shown a pivotal role of cyclophilins in auxin signaling and lateral root formation that includes perturbation of the activity of auxin-responsive Aux/IAA family proteins65,66. Certainly, these predictions must be further confirmed by experimental evidence.

Discussion

Primary Metabolism

Some enzymes of primary metabolism were highly activated in rolB-transformed cells, whereas some decreased in abundance. At first, these observations seem contradictory. However, we found that most of the enzymes that were hyper-activated in rolB-transformed cells have been shown to be highly responsive to various types of stress59 (Table 1). In general, rolB suppresses primary metabolism and activates anti-stress defense pathways in cells.

Chaperonin Family Proteins

Hsp70s are highly conserved in eukaryotes, and some their functions are conserved in animals and plants. In animals, overexpression of Hsp70 was found to confer tumorigenicity and provide a selective survival advantage to tumor cells due to its ability to inhibit multiple pathways of cell death, including apoptosis67. In the case of the rolB gene, we can see a similar picture, i.e., increased abundance of some Hsp70 proteins (Table 1) and inhibition of programmed cell death10. Therefore, rolB may function to provide favorable conditions for tumor growth after T-DNA integration. Only chloroplastic forms of Hsp proteins such as Hsp70-6, Hsp70-7, Hsp90-5/CR88 (synonym: Hsp88.1), 20-kDa chaperonin and chaperonin 60 subunit α1 were upregulated in rolB-transformed cells. Expression of genes encoding these proteins was also upregulated (Fig. 1). Indeed, recent data have shown the higher expression of genes encoding chloroplast heat-shock proteins in rolB-transformed tomato plants, compared with normal plants68.

It is presently unclear which reactions represent the direct action of RolB and which reactions compensate for this action. Presently, we assume that increased expression of chloroplastic heat shock proteins (Hsp70-6 and Hsp70-7, Hsp90-5, 20-kDa chaperonin and chaperonin 60 subunit α1) in rolB-transformed calli represents some kind of compensatory reaction. We propose the following development of events after the transformation. Basal levels of chaperones facilitate normal protein folding and guard the proteome against misfolding and aggregation. Increased expression of chaperones in normal Arabidopsis cells subjected to stress, which has been reported many times previously, is an adaptive response that enhances cell survival. The increased expression of chaperone proteins in rolB-transformed cells reflects the efforts of these cells to maintain homeostasis. These chaperone proteins also help tumor cells balance changes in cell biochemistry.

The enhanced expression of chaperonin family proteins in rolB-transformed calli can be linked with the decreased expression of cyclophilins CYP18-3 (ROC1), CYP19-2 (ROC6), CYP19-3 (ROC2), CYP20-2 and CYP20-3 (ROC4). Little is known about the functional connection of heat shock proteins with cyclophilins in plants69, but in animal and human studies, connections of this type have been demonstrated20. These interactions are critical in establishing tumor phenotypes through the disturbance of processes involved in protein folding, trafficking and degradation. Whereas these investigations are of high importance for human biology20, they are presently almost unknown for plant biology and represent an emerging (and intriguing) topic for understanding the formation of tumor phenotypes in plants.

Plant cells transformed with the rolB gene tolerate high temperatures11. Many properties of rolB-transformed cells resemble those of heat-acclimated plants, including inhibition of plant cell death, Hsp activation and induction of ascorbate peroxidases and other defense enzymes70. However, a fundamental difference is that the expression of cyclophilins is increased in heat-acclimated plants70 but decreased in rolB-expressing cells. Taken together, our results indicate that rolB affects the expression of chaperone-type proteins such as heat-shock proteins and cyclophilins. These chaperones seem to regulate several layers of developmental and defense processes and potentially can affect many components of the Arabidopsis signaling system, including the RPM1-RPS2 signaling module, auxin and cytokinin signaling, the calcium signaling system and secondary metabolism.

Effector-Triggered Immunity

According to the zig-zag model of the plant immune system71, pathogens have evolved virulence factors that promote pathogen growth by suppressing pattern-triggered immunity (PTI). To counteract the action of specific pathogen effectors, plants have evolved effector-triggered immunity (ETI)72. In Arabidopsis, the ETI receptor RPM1 is activated by phosphorylation of the RPM1-interacting protein RIN4. During activation of the RPS2 pathway, RPS2 physically interacts with RIN473. RPS2 initiates signaling based upon perception of RIN4 disappearance and induces plant resistance73.

The most probable scenario for rolB action is its primary effect which is inhibition of ROS, apoptosis and eventually cell immunity. However, rolB-transformed cells counteract this action in various ways. The first way is ROC1 suppression. Because ROC1 suppresses RPM1/RIN4 immunity in a PPIase-dependent manner46, it can be assumed that rolB-transformed cells, by suppressing ROC1, attempt to maintain a constitutively activated process that resembles ETI. Therefore, the final effects of rolB gene expression resemble ETI more than PTI. It is likely that RolB partially mimics the action of nucleotide-binding/leucine-rich-repeat (NLR) receptors that are necessary for ETI72,74.

On the other hand, RPM1 is an Hsp90-5 client protein75 (Fig. 2). Hsp90-5, together with cofactors, ensures dynamic interactions in the module Hsp90-5-PBS2/RAR1-SGT1, which regulates the stability and function of RPM175. Therefore, the current hypothesis is that rolB controls the RPM1-RPS2 signaling module in two ways: via ROC1-RIN4 and via Hsp90-5–RPM1 interactions.

RolB, Cyclophilins and RACK1A

Ito and Machida recently suggested that plant T-DNA oncogenes change the epigenetic status of the host chromatin through intrinsic histone chaperone activity17. Indeed, in both plants and animals, cyclophilins acting as PPIases and chaperones alter transcription by altering chromatin structure and by other mechanisms that include the recruiting of chromatin- and histone-modifying enzymes76. Another possible effect of cyclophilin silencing in rolB-expressing cells is silencing of RACK1A, an important protein that regulates the small RNA (miRNA and short interfering RNA)-processing machinery. Therefore, the action of the rolB gene could be similar to that of the 6b gene, the product of which targets key components of the small RNA processing machinery, namely both the DCL1-SE-HYL1 and RISC/AGO1 complexes77. Intriguingly, RACK1 suppression promotes gastric cancer by modulating the expression of miRNAs78. RACK1 inhibition may be important for rolB-mediated tumor progression in plants.

Secondary Metabolism

The mysterious ability of rolB to greatly activate secondary metabolism in transformed cells has been known for many years13. It was recently shown that expression of rolB in Arabidopsis thaliana calli leads to the activation of genes encoding secondary metabolism-specific MYB and bHLH transcription factors15. Accordingly, a higher transcript abundance of corresponding biosynthetic genes related to these factors was detected. The effect of rolB on the expression of transcription factors was highly specific; for example, rolB did not induce MYB111 or PAP1 expression and caused the conversion of MYB expression from cotyledon-specific to root-specific patterns15.

It should be noted that none of the regulatory proteins described in the present work whose expression was changed by rolB gene activity can be attributed to the common secondary metabolism activator pathways described earlier for Arabidopsis32. The rolB gene most likely does not affect secondary metabolism directly; its effect is more likely a part of general defense reactions. We suggested three signaling modules by which rolB might influence secondary metabolism: ROC4-RACK1A → MYC2 (MYB2-TT8; JAZ1-TT8); (VIK-HAI1-HAB1-ABI2)-MYB12 and ROC2-(CAM-CDPK) (Fig. 2). The first of these is based on the MYB2 signaling module, which connects secondary metabolism with hormone (JA, auxin, cytokinin and ethylene) signaling32. The second represents the connection between secondary metabolism and abscisic acid, which is mediated by HAI1-MYB12 interactions79. The third, ROC2-(CAM-CDPK) module, represents a pathway of secondary metabolism activation known as activation through calcium-dependent protein kinases80. Considering the observation that rolB is a more powerful activator of secondary metabolism than a constitutively expressed CDPK gene81, we suggest that more than one mechanism is involved in its activator function.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The analyses described in this work were performed using equipment from the Instrumental Centre for Biotechnology and Gene Engineering at the Institute of Biology and Soil Science. Financial support was provided by the Russian Science Foundation, Grant no. 18-44-08001 (V.P. Bulgakov) for proteomics and bioinformatics and RF President’s grant MK-491.2017.4 for young scientists (G.N. Veremeichik) for investigation of gene expression.

Author Contributions

Victor P. Bulgakov, data analysis, bioinformatics, manuscript writing. Yulia V. Vereshchagina, 2D gels, analysis. Dmitry V. Bulgakov, mass-spectrometry, analysis. Galina N. Veremeichik, qRCR, data analysis. Yuri N. Shkryl, qRCR, data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20694-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Delbarre A, et al. The rolB gene of Agrobacterium rhizogenes does not increase the auxin sensitivity of tobacco protoplasts by modifying the intracellular auxin concentration. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:563–569. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.2.563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cecchetti V, et al. Expression of rolB in tobacco flowers affects the coordinated process of anther dehiscence and style elongation. Plant J. 2004;38:512–525. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2004.02064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmülling T, Shell J, Spena A. Single genes from Agrobacterium rhizogenes influence plant development. EMBO J. 1988;7:2621–2629. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb03114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capone I, et al. Induction and growth properties of carrot roots with different complements of Agrobacterium rhizogenes T-DNA. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989;13:43–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00027334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurel C, et al. Alterations of auxin perception in rolB-transformed tobacco protoplasts. Time course of rolB mRNA expression and increase in auxin sensitivity reveal multiple control by auxin. Plant Physiol. 1994;105:1209–1215. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.4.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altamura MM, Capitani F, Gazza L, Capone I, Costantino P. The plant oncogene rolB stimulates the formation of flowers and root meristemoids in tobacco thin cell layers. New Phytol. 1994;126:283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb03947.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koltunow AM, Johnson SD, Lynch M, Yoshihara T, Costantino P. Expression of rolB in apomictic Hieracium piloselloides Vill. causes ectopic meristems in planta and changes in ovule formation, where apomixis initiates at higher frequency. Planta. 2001;214:196–205. doi: 10.1007/s004250100612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carmi N, Salts Y, Dedicova B, Shabtai S, Barg R. Induction of parthenocarpy in tomato via specific expression of the rolB gene in the ovary. Planta. 2003;217:726–735. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulgakov VP, et al. The rolB gene suppresses reactive oxygen species in transformed plant cells through the sustained activation of antioxidant defense. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:1371–1381. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.191494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gorpenchenko TY, et al. Can plant oncogenes inhibit programmed cell death? The rolB oncogene reduces apoptosis-like symptoms in transformed plant cells. Plant Signaling Behav. 2012;7:1–4. doi: 10.4161/psb.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulgakov VP, Shkryl YN, Veremeichik GN, Gorpenchenko TY, Vereshchagina YV. Recent advances in the understanding of Agrobacterium rhizogenes-derived genes and their effects on stress resistance and plant metabolism. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2013;134:1–22. doi: 10.1007/10_2013_179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arshad W, Haq IU, Waheed MT, Mysore KS, Mirza B. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of tomato with rolB gene results in enhancement of fruit quality and foliar resistance against fungal pathogens. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulgakov VP. Functions of rol genes in plant secondary metabolism. Biotechnol. Adv. 2008;26:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilshad E, Cusido RM, Ramirez Estrada K, Bonfill M, Mirza B. Genetic transformation of Artemisia carvifolia Buch with rol genes enhances artemisinin accumulation. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140266. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulgakov VP, Veremeichik GN, Grigorchuk VP, Rybin VG, Shkryl YN. The rolB gene activates secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis calli via selective activation of genes encoding MYB and bHLH transcription factors. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016;102:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terakura S, et al. An oncoprotein from the plant pathogen Agrobacterium has histone chaperone-like activity. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2855–2865. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito M, Machida Y. Reprogramming of plant cells induced by 6b oncoproteins from the plant pathogen Agrobacterium. J. Plant Res. 2015;128:423–435. doi: 10.1007/s10265-014-0694-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishibashi N, Kitakura S, Terakura S, Machida C, Machida Y. Protein encoded by oncogene 6b from Agrobacterium tumefaciens has a reprogramming potential and histone chaperone-like activity. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:572. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, Wen B. “Identification Card”: Sites on histone modification of cancer cell. Chin. Med. Sci. J. 2015;30:203–209. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(16)30001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taipale M, et al. A quantitative chaperone interaction network reveals the architecture of cellular protein homeostasis pathways. Cell. 2014;158:434–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vartholomaiou E, Echeverría PC, Picard D. Unusual suspects in the Twilight Zone between the Hsp90 interactome and carcinogenesis. Adv. Cancer Res. 2016;129:1–30. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeuchi M, Sugimoto K, Iwase A. Plant callus: mechanisms of induction and repression. Plant Cell. 2013;25:3159–3173. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.116053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu, H. G. et al. iTRAQ-based comparative proteomic analysis provides insights into somatic embryogenesis in Gossypium hirsutum L. Plant Mol. Biol. 10.1007/s11103-017-0681-x. (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Klubicová K, et al. Insights into the early stage of Pinus nigra Arn. somatic embryogenesis using discovery proteomics. J. Proteomics. 2017;169:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2017.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, et al. Induction and quantitative proteomic analysis of cell dedifferentiation during callus formation of lotus (Nelumbo nucifera Gaertn. spp. baijianlian) J. Proteomics. 2016;131:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reis RS, Vale Ede M, Heringer AS, Santa-Catarina C, Silveira V. Putrescine induces somatic embryo development and proteomic changes in embryogenic callus of sugarcane. J. Proteomics. 2016;130:170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou X, et al. Global analysis of differentially expressed genes and proteins in the wheat callus infected by Agrobacterium tumefaciens. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shkryl YN, et al. Individual and combined effects of the rolA, B and C genes on anthraquinone production in Rubia cordifolia transformed calli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;100:118–125. doi: 10.1002/bit.21727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carpentier SC, et al. Preparation of protein extracts from recalcitrant plant tissues: An evaluation of different methods for two-dimensional gel electrophoresis analysis. Proteomics. 2005;5:2497–2507. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou W, Petricoin EF, III, Longo C. Mass spectrometry-based biomarker discovery. Molecular profiling: methods and protocols. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;823:251–264. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-216-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vizcaíno JA, et al. 2016 update of the PRIDE database and related tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(D1):D447–D456. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bulgakov VP, Avramenko TV, Tsitsiashvili GS. Critical analysis of protein signaling networks involved in the regulation of plant secondary metabolism: focus on anthocyanins. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017;37:685–700. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2016.1141391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin M, Zhou X, Shen X, Mao C, Chen X. The predicted Arabidopsis interactome resource and network topology-based systems biology analyses. Plant Cell. 2011;23:911–922. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.082529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stark C, et al. BioGRID: A general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D535–D539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsitsiashvili, G., Sh. et al. Construction of subgraph from graph shortest ways. Applied Mathematical Sciences9, 3911–3916 (2015).

- 36.Tsitsiashvili, G., Sh., Bulgakov, V. P. & Losev, A. S. Factorization of directed graph describing protein network. Applied Mathematical Sciences11, 1925–1931 (2017).

- 37.Veremeichik GN, Shkryl YN, Bulgakov VP, Avramenko TV, Zhuravlev YN. Molecular cloning and characterization of seven class III peroxidases induced by overexpression of the agrobacterial rolB gene in Rubia cordifolia transgenic callus cultures. Plant Cell Rep. 2012;31:1009–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00299-011-1219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shkryl YN, et al. The production of class III plant peroxidases in transgenic callus сultures transformed with the rolB gene of Agrobacterium rhizogenes. J. Biotechnol. 2013;168:64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dixon DP, Skipsey M, Grundy NM, Edwards R. Stress-induced protein S-glutathionylation in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;138:2233–2244. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.058917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montero-Barrientos M, et al. Transgenic expression of the Trichoderma harzianum hsp70 gene increases Arabidopsis resistance to heat and other abiotic stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2010;167:659–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jungkunz I, et al. AtHsp70-15-deficient Arabidopsis plants are characterized by reduced growth, a constitutive cytosolic protein response and enhanced resistance to TuMV. Plant J. 2011;66:983–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim SH, et al. Characterization of a novel DWD protein that participates in heat stress response in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells. 2014;37:833–840. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2014.0224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romano PG, Horton P, Gray JE. The Arabidopsis cyclophilin gene family. Plant Physiol. 2004;134:1268–1282. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.022160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kundu N, Dozier U, Deslandes L, Somssich IE, Ullah H. Arabidopsis scaffold protein RACK1A interacts with diverse environmental stress and photosynthesis related proteins. Plant Signaling Behav. 2013;8:e24012. doi: 10.4161/psb.24012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cheng Z, et al. Pathogen-secreted proteases activate a novel plant immune pathway. Nature. 2015;521:213–216. doi: 10.1038/nature14243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M, et al. Proline isomerization of the immune receptor-interacting protein RIN4 by a cyclophilin inhibits effector-triggered immunity in Arabidopsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin R, Jez JM, Basra A, Zhang B, Schachtman DP. 14-3-3 proteins fine-tune plant nutrient metabolism. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur G, et al. Characterization of peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase- and calmodulin-binding activity of a cytosolic Arabidopsis thaliana cyclophilin AtCyp19-3. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0136692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Veremeichik GN, Shkryl YN, Pinkus SA, Bulgakov VP. Expression profiles of calcium-dependent protein kinase genes (CDPK1-14) in Agrobacterium rhizogenes pRiA4-transformed calli of Rubia cordifolia under temperature- and salt-induced stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2014;171:467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dominguez-Solis JR, et al. A cyclophilin links redox and light signals to cysteine biosynthesis and stress responses in chloroplasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:16386–16391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808204105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park SW, et al. Cyclophilin 20-3 relays a 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid signal during stress responsive regulation of cellular redox homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:9559–9564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218872110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ueda M, et al. The HALTED ROOT gene encoding the 26S proteasome subunit RPT2a is essential for the maintenance of Arabidopsis meristems. Development. 2004;131:2101–2111. doi: 10.1242/dev.01096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen JG, et al. RACK1 mediates multiple hormone responsiveness and developmental processes in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:2697–2708. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erl035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kurepa J, Toh-E A, Smalle JA. 26S proteasome regulatory particle mutants have increased oxidative stress tolerance. Plant J. 2008;53:102–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Speth C, Willing EM, Rausch S, Schneeberger K, Laubinger S. RACK1 scaffold proteins influence miRNA abundance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;76:433–445. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bulgakov VP, Veremeichik GN, Shkryl YN. The rolB gene activates the expression of genes encoding microRNA processing machinery. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015;37:921–925. doi: 10.1007/s10529-014-1743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marchand C, et al. New targets of Arabidopsis thioredoxins revealed by proteomics analysis. Proteomics. 2004;4:2696–2706. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200400805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park SK, et al. Heat-shock and redox-dependent functional switching of an h-type Arabidopsis thioredoxin from a disulfide reductase to a molecular chaperone. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:552–561. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Less H, Galili G. Principal transcriptional programs regulating plant amino acid metabolism in response to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:316–330. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.115733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Y, et al. The cyclophilin CYP20-2 modulates the conformation of BRASSINAZOLE-RESISTANT1, which binds the promoter of FLOWERING LOCUS D to regulate flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2013;25:2504–2521. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.110296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kodahl N, Müller R, Lütken H. The Agrobacterium rhizogenes oncogenes rolB and ORF13 increase formation of generative shoots and induce dwarfism in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. Plant Sci. 2016;252:22–29. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ceserani T, Trofka A, Gandotra N, Nelson T. VH1/BRL2 receptor-like kinase interacts with vascular-specific adaptor proteins VIT and VIK to influence leaf venation. Plant J. 2009;57:1000–1014. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berkowitz O, Jost R, Pollmann S, Masle J. Characterization of TCTP, the translationally controlled tumor protein, from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2008;20:3430–3447. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.061010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brioudes F, Thierry AM, Chambrier P, Mollereau B, Bendahmane M. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a conserved mitotic growth integrator in animals and plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16384–16389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007926107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ivanchenko MG, et al. The cyclophilin A DIAGEOTROPICA gene affects auxin transport in both root and shoot to control lateral root formation. Development. 2015;142:712–721. doi: 10.1242/dev.113225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jing H, et al. Peptidyl-prolyl isomerization targets rice Aux/IAAs for proteasomal degradation during auxin signalling. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7395. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murphy ME. The HSP70 family and cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1181–1188. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bettini PP, et al. Agrobacterium rhizogenes rolB gene affects photosynthesis and chlorophyll content in transgenic tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. J. Plant Physiol. 2016;204:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gupta D, Tuteja N. Chaperones and foldases in endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in plants. Plant Signaling Behav. 2011;6:232–236. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.2.15490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larkindale J, Vierling E. Core genome responses involved in acclimation to high temperature. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:748–761. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.112060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jones JD, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cui H, Tsuda K, Parker JE. Effector-triggered immunity: from pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015;66:487–511. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Axtell MJ, Staskawicz BJ. Initiation of RPS2-specified disease resistance in Arabidopsis is coupled to the AvrRpt2-directed elimination of RIN4. Cell. 2003;112:369–377. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henry E, Yadeta KA, Coaker G. Recognition of bacterial plant pathogens: local, systemic and transgenerational immunity. New Phytol. 2013;199:908–915. doi: 10.1111/nph.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hubert DA, et al. Cytosolic HSP90 associates with and modulates the Arabidopsis RPM1 disease resistance protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:5679–5689. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hanes SD. Prolyl isomerases in gene transcription. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1850:2017–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang M, et al. Molecular insights into plant cell proliferation disturbance by Agrobacterium protein 6b. Genes Dev. 2011;25:64–76. doi: 10.1101/gad.1985511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen L, et al. Loss of RACK1 promotes metastasis of gastric cancer by inducing a miR-302c/IL8 signaling loop. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3832–3841. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lumba S, et al. A mesoscale abscisic acid hormone interactome reveals a dynamic signaling landscape in Arabidopsis. Dev. Cell. 2014;29:360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shkryl YN, Veremeichik GN, Bulgakov VP, Zhuravlev YN. Induction of anthraquinone biosynthesis in Rubia cordifolia cells by heterologous expression of a calcium-dependent protein kinase gene. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011;108:1734–1738. doi: 10.1002/bit.23077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]