Abstract

Novel in vivo excision assays for monitoring the excised oligonucleotide products of nucleotide excision repair in UV-irradiated cells have provided unprecedented views of the kinetics and genomic distribution of repair events. However, an unresolved issue is the fate of the excised oligonucleotide products of repair and their mechanism of degradation. Based on our observation that decreases in excised oligonucleotide abundance coincide with the induction of apoptotic signaling in UV-irradiated cells, we considered the possibility that caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling contributes to excised oligonucleotide degradation or to a general inhibition of the excision repair system. However, genetic and pharmacological approaches to inhibit apoptotic signaling demonstrated that caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling does not affect excision repair or excised oligonucleotide stability. Nonetheless, our assay for detecting soluble DNAs produced by repair also revealed the production of larger DNAs following DNA damage induction that was dependent on caspase activation. We therefore further exploited the versatility of this assay by showing that soluble DNAs produced by both nucleotide excision repair and apoptotic signaling can be monitored simultaneously with a diverse set of DNA damaging agents. Thus, our in vivo excision repair assay provides a sensitive measure of both repair kinetics and apoptotic signaling in genotoxin-treated cells.

Introduction

The human nucleotide excision repair system removes a wide variety of lesions from DNA through a dual incision mechanism, in which the damaged nucleotides are essentially cut out of the DNA in the form of a small DNA oligonucleotide approximately 30 nt in length1,2. Though this phenomenon was initially demonstrated in vitro using defined DNA damage-containing templates and cell-free extracts3,4 or purified repair proteins5,6, nearly identical observations have subsequently been made using cultured cells exposed to UV or other related environmental carcinogens and anti-cancer compounds. The detection of these repair events in vivo was made possible by the fact that these excised oligonucleotides are readily solubilized during cell lysis, and, once purified, can be labeled, separated by electrophoresis, and detected via radioactivity or chemiluminescence7–10. Moreover, the fact that these excised DNAs are released from DNA in association with specific repair proteins7,11 has allowed for studies of post-excision repair events12,13 and for the mapping of DNA repair events throughout the genome2,14–18.

These assays for monitoring excision repair capture only a transient repair intermediate in nucleotide excision repair. Ultimately, the 30-nt-long, damage-containing excised oligonucleotides are degraded to smaller species that must be detected via other methods19. How these repair products are degraded is completely unknown13,20, but their efficient degradation and intracellular processing are likely important to general cell biology and to human health. Indeed, the aberrant localization and processing of DNA in the cytosol leads to the activation of innate immune pathways implicated in autoimmunity21–24, and mutations in DNases responsible for degrading different DNA species cause autoimmune disorders such as lupus erythematosus in both experimental animal models and human patients25–30. Defective processing of the excised oligonucleotide products of repair or of other DNA species may therefore contribute to human disease, and thus their mechanism of degradation needs to be characterized and understood.

Based on our observation that the induction of apoptotic signaling was correlated with a decrease in excised oligonucleotide abundance in cultured cells following UV exposure, we tested the hypothesis that nucleotide excision repair and/or excised oligonucleotide stability were directly regulated by caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling. Though our analyses showed no strong link between caspase signaling and repair inhibition, our assays for monitoring excision repair unexpectedly showed that caspase-dependent degradation of genomic DNA can be readily and simultaneously observed along with bona fide excision repair events. Thus, this discovery demonstrates the versatility of our assay for monitoring soluble DNAs that are generated in genotoxin-treated cells and should therefore facilitate future studies of DNA damage responses in human cells exposed to a wide variety of DNA damaging agents.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and genotoxin exposure

HeLa cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank of Seoul National University (Seoul, Korea). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. For UV exposure, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Gibco) and then exposed to the indicated doses of UV using a germicidal lamp that emits primarily 254 nm light. The intensity of radiation was determined by using a portable digital radiometer (UVX Digital radiometer UVP). Benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol-9,10-epoxide (BPDE) was obtained from the NCI Chemical Carcinogen Reference Standard Repository (Midwest Research Institute, MO). Cisplatin and camptothecin were purchased from Sigma. For treatment of these DNA-damaging agents, the indicated doses of each chemical compound were directly added to the culture medium at the indicated concentrations.

Caspase inhibition

Caspase inhibition was achieved by using Z-VAD-FMK (Promega) in the culture medium at 20 μM unless otherwise indicated. For siRNA-mediated knockdown of Caspase 3, siGENOME human Casp3 (836) siRNA SMARTpool (Dharmacon) was transfected into cells using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As a negative control for siRNA experiments, siGENOME Non-Targeting siRNA pool #1 (Dharmacon) was used.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were analyzed on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels (Invitrogen) and subjected to immunoblotting analysis. Antibodies used for immunoblotting included anti-cleaved PARP (#9546), anti-cleaved Caspase-3 (#9661), anti-GAPDH (#2118), anti-XPC (sc74410), anti-XPA (sc-853) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, and anti-RPA32 (NA18, Calbiochem), anti-p62 (sc-292), anti-p89 (sc-293), anti-Caspase-3 (#9665) from Cell Signaling Technology. Secondary antibodies included horseradish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse (sc-2005) and anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2004) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Chemiluminescence was visualized with Amersham ECL Western or Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) on an ImageQuant LAS 4000 Mini apparatus (GE Healthcare) and quantified using ImageQuant TL Software (GE Healthcare). The specificity of all commercially available antibodies used for immunoblotting was verified with appropriate size markers, and the graphed data validates the reproducibility our findings in at least two independent experiments.

Immunoslot blot assay

Genomic DNA was isolated from insoluble pellets obtained during the preparation of cell lysates and subjected to immunoslot blot analysis as described previously9,31.

Cell lysis and in vivo excision assay

Genotoxin-treated cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and harvested with a cell scraper at the indicated time points. After centrifugation (1,000 × g), the cell pellets were resuspended in a Triton X-100 lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, and 1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 15 min at 4 °C on a rotating mixer. Soluble cell lysates were prepared by centrifugation (20,000 × g) for 1 h at 4 °C and transferred to new tubes. Small portions of the lysates were saved for immunoblot analysis. The cell lysates were incubated with RNase A (10 μg/ml) and RNase T1 (20 units/ml) for 20 min at 37 °C, and then treated with 0.15 mg/ml of proteinase K for 30 min at 55 °C. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the extracted DNA samples were resuspended in TE buffer, and then subjected to labeling with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT) and the nucleotide analog biotin-11-dUTP as described previously8,9. Briefly, the resuspended DNA was 3′-end labeled with 2 μM of biotin-11-dUTP (Biotium, Inc.) and 0.2 units/μl of TdT (New England Biolabs) in 1X TdT reaction buffer supplemented with 0.25 mM CoCl2 for 30 min at 37 °C. The labeling reactions were stopped by addition of 10 mM EDTA. About 100 ng of 10 bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen) was labeled in an identical reaction for use as a DNA marker during gel electrophoresis. The reactions were then treated with RNase A (10 μg/ml) and RNase T1 (20 units/ml) for 20 min at 37 °C and incubated with 0.4% SDS and 40 μg/ml of proteinase K for 30 min at 55 °C. After phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the labeled DNA samples were separated on 10–12% TBE-urea gels, transferred onto a modified nylon membrane (Zeta-Probe membrane by Bio-Rad or Biodyne B membrane by Pierce), and then fixed by UV crosslinking. The membrane was incubated with 1X PBS containing 2% SDS for 30 min and incubated with streptavidin-HRP conjugates (Thermo Scientific) in 1× PBS containing 2% SDS for 30 min. The membrane was then washed three times for 10 min with 1X PBS containing 0.5% SDS and incubated with 200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9.0) containing 10 mM MgCl2 for 5 min. Chemiluminescence was visualized with Amersham ECL Western or Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare) on ImageQuant LAS 4000 Mini apparatus (GE Healthcare) and quantified by ImageQuant TL Software (GE Healthcare). Detection of biotin-labeled DNA could also be achieved with the Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The entire blot was probed with streptavidin-HRP conjugates, and the entire image is displayed in each of the figures along with longer exposures of the region of the gel corresponding to the excised products of repair. To determine the size of DNA fragments, 10 bp DNA ladder (Invitrogen) was used.

Immunoprecipitation of excised oligomers

Detection of excised oligomers containing specific UV photoproducts was performed as previously described7–9.

Results

Nucleotide excision repair and apoptotic signaling show distinct kinetics in UV-irradiated cells

The human nucleotide excision repair system responds to UV-induced DNA damage by removing UV photoproducts from the genome in the form of short DNA oligonucleotides approximately 30 nt in length both in vitro3–5 and in vivo7,8,14. These primary repair products, as well as secondary, partially degraded products approximately 18- and 24-nt in length, are released from duplex DNA bound to specific DNA repair proteins11,32 and can be readily extracted from UV-irradiated cells and separated from bulk genomic DNA by using a mild lysis buffer and high-speed centrifugation8,9. The small, soluble repair products are then purified, labeled on the 3′ end with a biotinylated nucleotide, and electrophoresed on a sequencing gel. Following electrophoretic transfer to a nylon membrane, the DNAs can be visualized with streptavidin-bound HRP and chemiluminescent detection10. An example of this repair assay in HeLa cells exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC and then harvested at various time points following irradiation is shown in Fig. 1A (top panel).

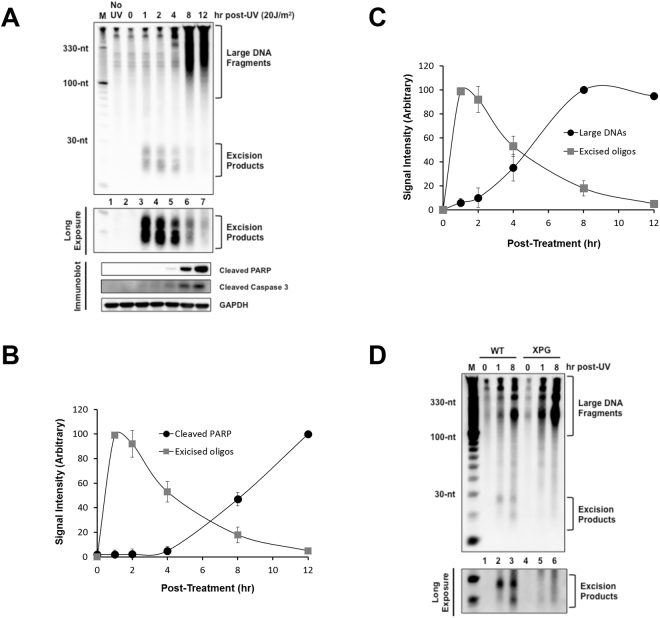

Figure 1.

Correlation between apoptotic signaling and the generation of large DNAs with decreased generation of excised oligonucleotide repair products. (A) Analysis of large DNA fragments and excised oligomers released from genomic DNA following UV irradiation. HeLa cells were exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC and incubated for the indicated time points. After extraction of low molecular weight of DNAs from the cells, the DNA molecules were labeled with biotin at 3′-end using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT). The labeled DNA molecules were separated by gel electrophoresis, transferred to a nylon membrane and immobilized by UV cross-linking. The membrane was then incubated with HRP-conjugated streptavidin, and the labeled DNA molecules were detected with a chemiluminescence reagent (upper panel). A small portion of the UV-irradiated cells were lysed and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) Quantification of the excised oligonucleotide repair products and cleaved PARP signals as shown in (A). The relative signal intensities were determined by setting the highest signal to 100. The results were quantified and are plotted as mean and standard deviations. (C) Quantitative analysis of the excised repair products and the large DNA molecules. (D) Wild-type (AA8) and XPG mutant (UV135) CHO cell lines were exposed to UV and processed as described above for the detection of soluble DNAs.

As previously reported, the peak generation of these excised oligonucleotide repair products occurs 1 h following UV exposure8,9. At later time points, the steady state level of the excised oligonucleotides decreases, such that by 8–12 h post-UV, the excised oligonucleotide products of repair are barely visible. The low level of repair products at these time points is not due to the completion of UV photoproduct repair, however, because immunoslot blot analysis of the genomic DNA from these cells revealed that more than 60% of UV-induced CPDs remain in genomic DNA as unrepaired potential substrates for the nucleotide excision repair machinery 8 to 12 h after UV exposure. Whether the low level of repair products that are present at these time points is due to a lower rate of damage excision or to an increased rate of excised oligonucleotide degradation is not known.

Nonetheless, the large fluence of UV used in this experiment (20 J/m2) is known to saturate nucleotide excision repair capacity8 and to significantly compromise cell viability. Because caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling is a major mechanism by which UV induces cell death33, we therefore also examined the induction of apoptotic signaling in the same cell lysates that were used to monitor excision repair. As shown in Fig. 1A (bottom), cleavage of two well-known apoptotic markers (PARP and caspase 3) was observed 8–12 h post-UV, which corresponds to the same time points at which the excised oligonucleotides become barely visible. Quantitation of excision repair and PARP cleavage from several independent experiments revealed that the increase in apoptotic signaling was correlated with a decrease in excised oligonucleotide abundance (Fig. 1B).

Interestingly, examination of soluble DNAs from the UV-irradiated cells also revealed the emergence of a larger species of DNAs that began at the origin of the gel and smeared down to a size of approximately 70 nt in length (Fig. 1A, top). The presence of these DNAs in the cell lysates coincided in time with the activation of apoptotic signaling and with the decrease in excised oligonucleotides (Fig. 1B,C). Importantly, these large DNAs were also observed in UV-irradiated cells that are deficient in nucleotide excision repair (Fig. 1D), which demonstrates that the nucleotide excision repair system is not responsible for generating these large, soluble DNA fragments.

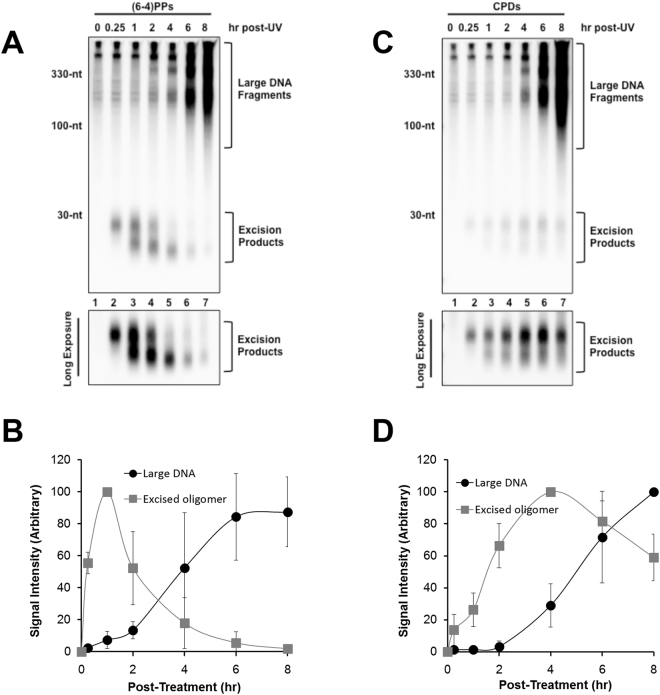

The analysis of excised oligonucleotides shown in Fig. 1A represents the totality of diverse excision products that are generated by the nucleotide excision repair system following UV exposure. To determine whether the kinetics of repair of specific UV photoproducts exhibit a similar inverse correlation with apoptotic signaling, we used anti-(6-4)PP and anti-CPD antibodies to immunoprecipitate soluble DNAs containing the corresponding specific DNA lesions. As shown in Fig. 2A, (6-4)PP-containing repair products are generated within minutes following UV exposure, peak 1 h after UV irradiation, and then begin to rapidly decrease in abundance. However, examination of the top of the gel revealed larger (6-4)PP-containing DNAs that became apparent at late time points after UV exposure. Quantitation of several independent experiments confirmed the opposing kinetics of the excision repair products and large DNAs (Fig. 2B). Though CPDs are recognized less efficiently than (6-4)PPs34 and thus are removed from the genome at a slower rate, we noted a similar pattern of large and small DNAs containing CPDs. Thus, large CPD-containing DNAs become more abundant at late time points after UV as the canonical CPD-containing repair products became less abundant (Fig. 2C,D).

Figure 2.

Emergence of large DNA fragments containing (6-4)PPs and CPDs at later time points with decreased generation of excision repair products. UV-irradiated HeLa cells were harvested at the indicated time points and subjected to extraction of soluble DNA fragments released from genomic DNA. The extracted DNA molecules were then immunoprecipitated with anti-(6-4)PPs (A) or anti-CPDs antibodies (C) and analyzed as described in Fig. 1(A). The relative intensities of the excised oligonucleotides and the large DNA molecules containing (6-4)PPs and CPDs were quantified and shown in (B) and (D), respectively.

Thus, we conclude that the generation and/or stability of the excised oligonucleotide products of nucleotide excision repair show an opposite pattern in comparison with apoptotic signaling and the generation of large, soluble, UV photoproduct-containing DNAs. The activation of apoptosis is therefore correlated with a reduction in the excised oligonucleotides and the emergence of a new, larger soluble DNA species. The fact that these large DNAs contain bona fide UV photoproducts suggests that DNA fragments containing UV photoproducts are released from bulk genomic DNA to a some extent in dying cells.

Nucleotide excision repair and apoptotic signaling show different kinetics in cells exposed to UV mimetics

The nucleotide excision repair system acts on DNA adducts induced by a wide variety of agents, including bulky aromatic lesions induced by the environmental carcinogen BPDE35–37 and intrastrand crosslinks caused by the anti-cancer drug cisplatin38–41. Because we previously showed that excised oligonucleotide products of repair could be observed in cells treated with these compounds9, we next quantified the level of excised oligonucleotides, cleaved PARP, and large, soluble DNAs as a function of time in cells treated with BPDE and cisplatin. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, we show that maximal abundance of the excision repair products occurred prior to the generation of cleaved PARP and the large DNAs, which became more abundant as the repair product signal began to decrease. We conclude from these experiments that multiple DNA damaging agents that generate substrates for the nucleotide excision repair system and induce apoptosis also cause the formation of large, soluble DNAs that are generated coincident with apoptotic signaling. Moreover, a decrease in either repair rate or excised oligonucleotide stability of these diverse forms of DNA damage is correlated in time with the activation of caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling.

Apoptotic signaling does not affect excision repair rate, excised oligonucleotide stability, or excision repair protein levels

Given that apoptotic signaling is a highly coordinated enzymatic process that maintains cellular energy supplies during cell death42,43, the notion that apoptotic signaling could essentially “turn off” nucleotide excision repair to avoid wasting cellular energy would appear to be a reasonable hypothesis. To test this idea, we therefore pre-treated cells with DMSO or the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK prior to exposure to a high dose of UV. As shown in Fig. 3A and quantified in Fig. 3B, this treatment greatly reduced the amount of cleaved PARP that was present in the cells following the UV exposure. Interestingly, we also noted that the caspase inhibitor significantly abrogated the generation of the large, soluble DNA species that are generated in cells at late time points following UV irradiation (Fig. 3A,C). This result demonstrates that these large DNA species are not a result of simple DNA breaks produced by general DNA metabolism that undergo non-specific nucleolytic processing. Rather, the fact that caspase inhibition blocks their production shows that these DNAs are specifically generated in a caspase-dependent manner.

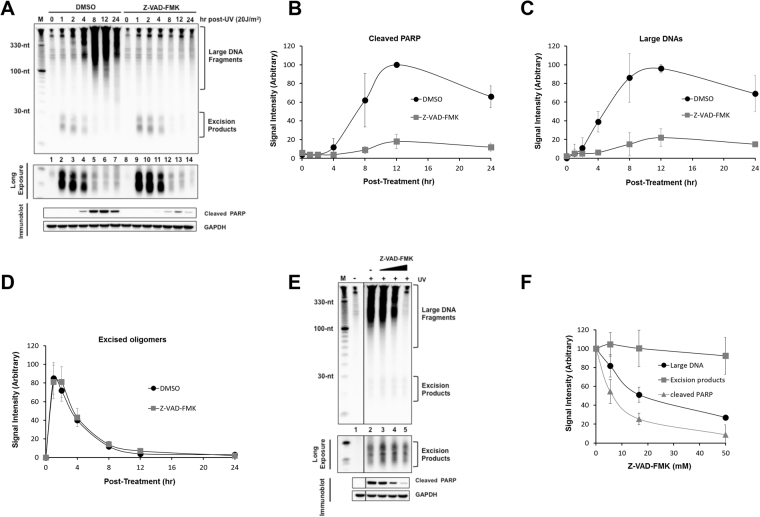

Figure 3.

Caspase inhibition prevents PARP cleavage and generation of large DNA fragments but does not affect excision repair activity. (A) Effects of caspase inhibition on the generation of large DNA fragments and excised oligomers released from genomic DNA following UV irradiation. HeLa cells were pre-incubated with DMSO or the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM) for 1 h and then exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC. The UV-irradiated cells were further incubated, harvested at the indicated time points, and analyzed for generation of large DNAs and excised oligonucleotides released from genomic DNA. Levels of cleaved PARP (B), generation of large DNAs (C) and excised oligos (D) were quantified and are presented as the mean values ± standard deviation. (E) Dose-dependent inhibition of caspase. DMSO or Z-VAD FMK (20 μM)-treated HeLa cells were exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC, harvested 8 h later and analyzed for the generation of large DNAs, excised oligomers. The image was cropped in order to place a non-irradiated negative control adjacent to the UV-treated samples. (F) Levels of cleaved PARP, generation of large DNAs and excised oligos in (E) were quantified and are presented as the mean values ± standard deviation.

In contrast, and somewhat unexpectedly, the level of excised oligonucleotides that were present in the UV-irradiated cells was not affected to any significant extent by caspase inhibition (Fig. 3A,D). Moreover, experiments varying the dose of the caspase inhibitor showed that although the use of increasing concentrations of the Z-VAD-FM resulted in a clear reduction in PARP cleavage and the production of large, soluble DNAs, the canonical excision repair products were unaffected (Fig. 3E,F). These results indicate that apoptotic signaling does not have a significant impact on either the generation or stability of the excised oligonucleotide products of nucleotide excision repair.

As we previously showed that the large DNA species that are present at later time points following UV exposure contain specific UV photoproducts (Fig. 2), we repeated our experiments with UV-irradiated cells treated with the caspase inhibitor but used anti-CPD and anti-(6-4)PP antibodies to isolate specific UV photoproduct-containing DNAs. As shown in Fig. 4A and quantified in Fig. 4B, treatment with the caspase inhibitor largely abrogated the generation of the large damage-containing DNAs but did not significantly impact the generation of the canonical excision repair products.

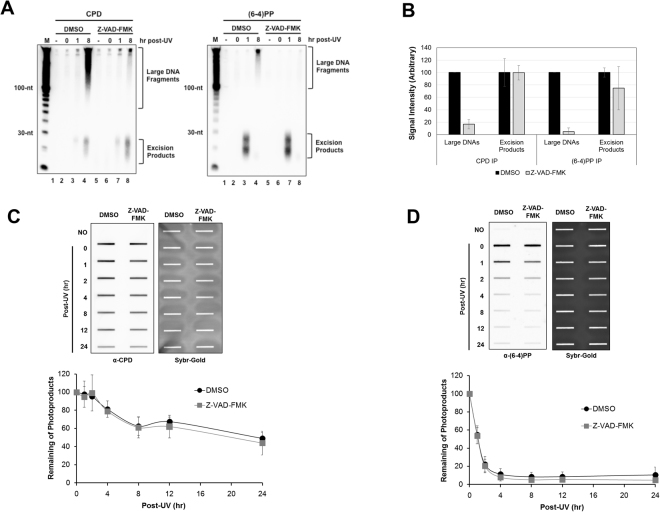

Figure 4.

Effects of caspase inhibition on the generation of large DNA fragments containing specific UV photoproducts. (A) DMSO or Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM) treated-HeLa cells were exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC, harvested at the indicated time points, and subjected to extraction of soluble DNA fragments. The purified DNAs were immunoprecipitated with anti-CPDs (left) or anti-(6-4)PPs (right) and analyzed as described in Fig. 1(A). (B) Quantitative analysis is shown for the levels of large DNAs and excised oligomers. (C and D) Genomic DNA was isolated from DMSO or Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM) treated-HeLa cells after UV-irradiation and then used in immune-slot blot assays with antibodies against CPDs (C) and (6-4)PPs (D). The Sybr-Gold staining shows equal loading of total genomic DNA. Quantitative analyses of repair kinetics for CPDs and (6-4)PPs are shown below the representative images.

We next wished to use an independent experimental methodology to confirm our finding that apoptotic signaling does not affect nucleotide excision repair. We therefore used immunoslot blot analysis to monitor the levels of unrepaired UV photoproducts in genomic DNA from UV-irradiated cells that were treated or not with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. As shown in Fig. 4C, approximately 50% of CPDs were removed from genomic DNA by 24 after UV exposure, regardless of the treatment with the caspase inhibitor. Though repaired at a faster rate, (6-4)PP removal was similarly unaffected by caspase inhibition (Fig. 4D). We conclude from these experiments that caspase inhibition does not affect UV photoproduct removal rate or excised oligonucleotide stability.

The caspases that are activated during apoptosis cleave a variety of cellular proteins to abrogate unnecessary biochemical processes and conserve cellular energy for apoptosis44. However, our observation that caspase inhibition does not affect nucleotide excision repair rate or excised oligonucleotide stability suggests that nucleotide excision repair proteins may not be targeted by canonical apoptotic caspase signaling. We therefore pre-treated cells with DMSO or the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK prior to exposure to a high dose of UV and then prepared soluble protein lysates at various time points following irradiation. Though caspase inhibition largely blocked the generation of cleaved PARP, the protein levels of several essential nucleotide excision repair proteins were not significantly affected by either UV or the caspase inhibitor (Supplementary Figure 2). These results therefore further validate our findings that apoptotic signaling does not influence nucleotide excision repair.

Large, soluble DNAs are a measure of DNA damage-induced apoptotic signaling

To confirm our observations that the generation of large, soluble DNAs in UV-irradiated cells could be blocked via the use of a caspase inhibitor, we next used siRNAs to silence the expression of the caspase 3. As shown in Fig. 5A, the siRNAs led to a reduction in UV-induced PARP cleavage. Moreover, the caspase 3 knockdown also partially abrogated the generation of the large, soluble DNA species that appear at late time points following UV exposure (Fig. 5A,B). In contrast, and similar to the results with the pan-caspase inhibitor, the use of the caspase 3 siRNAs did not affect the generation or stability of the small, canonical excised oligonucleotide products of nucleotide excision repair (Fig. 5C). We conclude that although apoptotic signaling does not affect the activity of the nucleotide excision repair system in UV-irradiated cells, it does generate larger soluble DNA species that can readily observed with our method for detecting soluble DNA repair products.

Figure 5.

Effects of caspase 3 knockdown on the generation of large DNAs and excised oligomers. (A) HeLa cells were transfected with control non-targeting siRNA or caspase 3 siRNA, exposed to 20 J/m2 of UVC 48 h later and harvested at the indicated time points. The cells were analyzed for the soluble DNAs (upper panel), and used for immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies (lower panel). Quantitative analysis of the generation of large DNAs (B) and excised oligomers (C) is also shown.

We next wished to determine whether the large, soluble DNA species that are observed in cells treated with UV mimetic compounds9 are also generated in a caspase-dependent manner. As shown in Fig. 6A and quantified in Fig. 6B, the large, soluble DNAs that are produced at late time points after administration with the environmental carcinogen BPDE could be significantly reduced by treatment of the cells with the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. However, analyses of the small, excised products of nucleotide excision repair showed that repair was not affected to a significant extent by caspase inhibition.

Figure 6.

Generation of caspase-dependent large DNA fragments in response to other DNA damaging agents. (A) Effects of caspase inhibition on BPDE-treated cells. HeLa cells were pre-incubated with DMSO or Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM), treated with BPDE (1 μM) and harvested at the indicated time points. The cells were then analyzed for the generation of large DNA fragments and excised oligomers released from genomic DNA. Quantitative analysis of the generation of large DNAs (B) is also shown. (C) Effects of caspase inhibition on CPT-treated cells. HeLa cells were pre-incubated with DMSO or Z-VAD-FMK (20 μM), treated with CPT (20 μM) and analyzed as in (A). A longer exposure of the 20–40 nt region of the blot is provided to show that camptothecin does not induce canonical NER products. Quantitative analysis of the generation of large DNAs is shown in (D).

Camptothecin is a commonly used anti-cancer drug that traps topoisomerase I on the DNA and therefore generates single-strand breaks in DNA45,46. Transcription and replication at these sites can convert the single-strand breaks intermediates into potentially lethal double-strand breaks. Using our assay for monitoring soluble DNAs, we observed a robust production of large, soluble DNAs that coincided in time with the cleavage of PARP (Fig. 6C). Moreover, these DNAs were found to be due to apoptotic signaling, as caspase inhibition largely abolished the production of the large, soluble DNAs (Fig. 6C,D). Because camptothecin does not generate a substrate for the nucleotide excision repair machinery, no small DNAs were observed in these experiments. Taken together, our in vivo excision repair assay for monitoring the excised oligonucleotide products of excision repair in cultured cells provides not only a high resolution view of repair kinetics but also a sensitive measure of apoptotic signaling, which to our knowledge has not been reported elsewhere.

Discussion

Here we showed that although apoptotic signaling does not affect the generation or stability of the excised oligonucleotide products of nucleotide excision repair, it does produce a DNA species that can be readily visualized using the same experimental methodology for monitoring the small oligonucleotides products of canonical nucleotide excision repair. Though we have previously reported observing these larger DNA species in cells treated DNA damaging agents8,9, their source and mechanism of production remained unknown. The fact that the generation of these DNAs is largely attenuated in the presence of a caspase inhibitor (Fig. 3) or with genetic disruption of caspase 3 (Fig. 5) indicates that they are primarily produced by caspase-mediated apoptotic signaling. Caspase-mediated fragmentation of genomic DNA is considered a biochemical hallmark of apoptosis47–49. This cleavage of chromosomal DNA into oligonucleosomal fragments is caused by the activation of endogenous endonucleases such as caspase 3-activated DNase (CAD)50, which leads to DNA laddering as multiples of ~180 bp oligonucleosomal size fragments that are visible by agarose gel electrophoresis49. The TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling) assay is also widely used to detect apoptotic cells; however, it may not discriminate from DNA repair intermediates51. Though the use of terminal transferase labeling, urea-PAGE, and chemiluminescent detection, we show here that additional caspase-mediated degradation of DNA down to ~70 nt in length can be readily observed on the same gels that are used to visualize the ~30-nt-long DNA products of nucleotide excision repair. Thus, our ability to now define the origin of the large, soluble DNAs as arising from apoptotic signaling (Figs 3–6) will be useful in future analyses of nucleotide excision repair and other DNA damage responses in both cultured cells and animal tissues. However, we note that there may be some quantitative limitations to the existing assay, and care must be taken to observe repair and apoptotic signals within the linear range of detection. Moreover, terminal transferase may add multiple biotinylated nucleotides to the 3′ ends of the DNAs, which could amplify the observed signals. Because the excised oligonucleotide products of repair in our experiments are of the expected size (20–30 nt), terminal transferase does not appear to be adding multiple nucleotides to these DNAs to any significant extent. In contrast, it is not known whether terminal transferase adds multiple nucleotides to the apoptotic DNAs, and thus it is possible that the large, apoptotic DNA signals that are observed may be artificially amplified by the current methodology.

The ability to detect damage-containing excision products and apoptotic fragments will be useful for biochemical studies addressing their fate in cells and tissues, including in identifying novel proteins that associate with these DNA species to promote their ultimate degradation. UV-irradiated DNA has been shown to less efficiently degraded by cellular nucleases52 and thus, if inappropriately localized to the cytosol, these DNAs have the potential to stimulate innate immune signaling pathways that are implicated in autoimmune disorders21–24. Thus, in addition to understanding the fate of the canonical excised products of nucleotide excision repair, it will be interesting to determine how cells and tissues process these larger, damage-containing DNAs that are generated during apoptosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science under the project “Development of bio-clinical measurement standards” [17011048] and also in part by the R&D Convergence Program of NST (National Research Council of Science and Technology) of Republic of Korea [CAP-15-10-KRICT].

Author Contributions

M.G.K. and J.H.C. designed the study; S.B., S.H. and D.K. conducted the experiments; S.B., S.H., M.G.K. and J.H.C. analyzed data; S.B. and S.H. prepared the figures; M.G.K. and J.H.C. wrote the main manuscript text; all the authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Soyun Baek and Sueji Han contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20527-6.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Michael G. Kemp, Email: mike.kemp@wright.edu

Jun-Hyuk Choi, Email: junchoi@kriss.re.kr.

References

- 1.Reardon JT, Sancar A. Nucleotide excision repair. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2005;79:183–235. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(04)79004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu, J., Selby, C. P., Adar, S., Adebali, O. & Sancar, A. Molecular mechanisms and genomic maps of DNA excision repair in E. coli and humans. J Biol Chem, 10.1074/jbc.R117.807453 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Huang JC, Svoboda DL, Reardon JT, Sancar A. Human nucleotide excision nuclease removes thymine dimers from DNA by incising the 22nd phosphodiester bond 5′ and the 6th phosphodiester bond 3′ to the photodimer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3664–3668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Svoboda DL, Taylor JS, Hearst JE, Sancar A. DNA repair by eukaryotic nucleotide excision nuclease. Removal of thymine dimer and psoralen monoadduct by HeLa cell-free extract and of thymine dimer by Xenopus laevis oocytes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1931–1936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mu D, et al. Reconstitution of human DNA repair excision nuclease in a highly defined system. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:2415–2418. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans E, Moggs JG, Hwang JR, Egly JM, Wood RD. Mechanism of open complex and dual incision formation by human nucleotide excision repair factors. EMBO J. 1997;16:6559–6573. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J, et al. Nucleotide excision repair in human cells: fate of the excised oligonucleotide carrying DNA damage in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20918–20926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.482257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi JH, et al. Highly specific and sensitive method for measuring nucleotide excision repair kinetics of ultraviolet photoproducts in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e29. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi JH, Kim SY, Kim SK, Kemp MG, Sancar A. An Integrated Approach for Analysis of the DNA Damage Response in Mammalian Cells: Nucleotide excision repair, dna damage checkpoint, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:28812–28821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.690354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Kemp MG, Choi JH. Detection of the Excised, Damage-containing Oligonucleotide Products of Nucleotide Excision Repair in Human Cells. Photochem Photobiol. 2017;93:192–198. doi: 10.1111/php.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kemp MG, Reardon JT, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Sancar A. Mechanism of release and fate of excised oligonucleotides during nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22889–22899. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.374447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kemp MG, Gaddameedhi S, Choi JH, Hu J, Sancar A. DNA repair synthesis and ligation affect the processing of excised oligonucleotides generated by human nucleotide excision repair. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26574–26583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.597088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kemp MG, Hu J. PostExcision Events in Human Nucleotide Excision Repair. Photochem Photobiol. 2017;93:178–191. doi: 10.1111/php.12641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu J, Adar S, Selby CP, Lieb JD, Sancar A. Genome-wide analysis of human global and transcription-coupled excision repair of UV damage at single-nucleotide resolution. Genes Dev. 2015;29:948–960. doi: 10.1101/gad.261271.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adar S, Hu J, Lieb JD, Sancar A. Genome-wide kinetics of DNA excision repair in relation to chromatin state and mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E2124–2133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1603388113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, Lieb JD, Sancar A, Adar S. Cisplatin DNA damage and repair maps of the human genome at single-nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:11507–11512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614430113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li W, et al. Human genome-wide repair map of DNA damage caused by the cigarette smoke carcinogen benzo[a]pyrene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:6752–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706021114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, Adebali O, Adar S, Sancar A. Dynamic maps of UV damage formation and repair for the human genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:6758–6763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706522114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douki T, von Koschembahr A, Cadet J. Insight in DNA Repair of UV-induced Pyrimidine Dimers by Chromatographic Methods. Photochem Photobiol. 2017;93:207–215. doi: 10.1111/php.12685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemp MG, Sancar A. DNA excision repair: where do all the dimers go? Cell Cycle. 2012;11:2997–3002. doi: 10.4161/cc.21126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cai X, Chiu YH, Chen ZJ. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING pathway of cytosolic DNA sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2014;54:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemp MG. Crosstalk Between Apoptosis and Autophagy: Environmental Genotoxins, Infection, and Innate Immunity. J Cell Death. 2017;9:1179670716685085. doi: 10.1177/1179670716685085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gasser S, et al. Sensing of dangerous DNA. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;165:33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen YJ, et al. Genome-derived cytosolic DNA contributes to type I interferon expression and immunogenicity of B-cell lymphoma cells. Cytokine. 2015;76:581–582. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rice GI, Rodero MP, Crow YJ. Human disease phenotypes associated with mutations in TREX1. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10875-015-0147-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasutomo K, et al. Mutation of DNASE1 in people with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Genet. 2001;28:313–314. doi: 10.1038/91070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stetson DB, Ko JS, Heidmann T, Medzhitov R. Trex1 prevents cell-intrinsic initiation of autoimmunity. Cell. 2008;134:587–598. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fye JM, Orebaugh CD, Coffin SR, Hollis T, Perrino FW. Dominant mutation of the TREX1 exonuclease gene in lupus and Aicardi-Goutieres syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32373–32382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.276287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Napirei M, et al. Features of systemic lupus erythematosus in Dnase1-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2000;25:177–181. doi: 10.1038/76032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyel PA. Dnases in health and disease. Dev Biol. 2017;429:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2017.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaddameedhi S, et al. Similar nucleotide excision repair capacity in melanocytes and melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4922–4930. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mu D, Wakasugi M, Hsu DS, Sancar A. Characterization of reaction intermediates of human excision repair nuclease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28971–28979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batista LF, Kaina B, Meneghini R, Menck CF. How DNA lesions are turned into powerful killing structures: insights from UV-induced apoptosis. Mutat Res. 2009;681:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Branum ME, Reardon JT, Sancar A. DNA repair excision nuclease attacks undamaged DNA. A potential source of spontaneous mutations. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:25421–25426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101032200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de los Santos C, et al. Influence of benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide chirality on solution conformations of DNA covalent adducts: the (−)-trans-anti-[BP]G.C adduct structure and comparison with the (+)-trans-anti-[BP]G.C enantiomer. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5245–5252. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cosman M, et al. Solution conformation of the (+)-cis-anti-[BP]dG adduct in a DNA duplex: intercalation of the covalently attached benzo[a]pyrenyl ring into the helix and displacement of the modified deoxyguanosine. Biochemistry. 1993;32:4145–4155. doi: 10.1021/bi00067a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alexandrov K, Rojas M, Satarug S. The critical DNA damage by benzo(a)pyrene in lung tissues of smokers and approaches to preventing its formation. Toxicol Lett. 2010;198:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jamieson ER, Lippard SJ. Structure, Recognition, and Processing of Cisplatin-DNA Adducts. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2467–2498. doi: 10.1021/cr980421n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zamble DB, Mu D, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lippard SJ. Repair of cisplatin–DNA adducts by the mammalian excision nuclease. Biochemistry. 1996;35:10004–10013. doi: 10.1021/bi960453+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang JC, Zamble DB, Reardon JT, Lippard SJ, Sancar A. HMG-domain proteins specifically inhibit the repair of the major DNA adduct of the anticancer drug cisplatin by human excision nuclease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:10394–10398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang D, Hara R, Singh G, Sancar A, Lippard SJ. Nucleotide excision repair from site-specifically platinum-modified nucleosomes. Biochemistry. 2003;42:6747–6753. doi: 10.1021/bi034264k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philchenkov A. Caspases: potential targets for regulating cell death. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:432–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robertson JD, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Review: nuclear events in apoptosis. J Struct Biol. 2000;129:346–358. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pommier Y. Topoisomerase I inhibitors: camptothecins and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:789–802. doi: 10.1038/nrc1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pommier Y. DNA topoisomerase I inhibitors: chemistry, biology, and interfacial inhibition. Chem Rev. 2009;109:2894–2902. doi: 10.1021/cr900097c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang JH, Xu M. DNA fragmentation in apoptosis. Cell Res. 2000;10:205–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wyllie AH. Glucocorticoid-induced thymocyte apoptosis is associated with endogenous endonuclease activation. Nature. 1980;284:555–556. doi: 10.1038/284555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Enari M, et al. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature. 1998;391:43–50. doi: 10.1038/34112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watanabe M, et al. The pros and cons of apoptosis assays for use in the study of cells, tissues, and organs. Microsc Microanal. 2002;8:375–391. doi: 10.1017/S1431927602010346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gehrke N, et al. Oxidative damage of DNA confers resistance to cytosolic nuclease TREX1 degradation and potentiates STING-dependent immune sensing. Immunity. 2013;39:482–495. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.