Abstract

Introduction: Vaccination against human papillomavirus (HPV) is routinely recommended for ages 11–12, yet in 2016 only 49.5% of women and 37.5% of men had completed the three-dose series in the United States. Offering information and cues to action through a serious videogame for preteens may foster HPV vaccination awareness, information seeking, and communication.

Materials and Methods: An iterative process was used to develop an interactive videogame, Land of Secret Gardens. Three focus groups were conducted with 16 boys and girls, ages 11–12, for input on game design, acceptability, and functioning. Two parallel focus groups explored parents' (n = 9) perspectives on the game concept. Three researchers identified key themes.

Results: Preteens wanted a game that is both entertaining and instructional. Some parents were skeptical that games could be motivational. A back-story about a secret garden was developed as a metaphor for a preteen's body and keeping it healthy. The goal is to plant a lush secret garden and protect the seedlings by treating them with a potion when they sprout to keep them healthy as they mature. Points to buy seeds and create the potion are earned by playing mini-games. Throughout play, players are exposed to messaging about HPV and the benefits of the vaccine. Both boys and girls liked the garden concept and getting facts about HPV. Parents were encouraged to discuss the game with their preteens.

Conclusion: Within a larger communication strategy, serious games could be useful for engaging preteens in health decision making about HPV vaccination.

Keywords: : Preteen, Videogame, HPV, Vaccination, Communication

Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the United States, causes genital warts, and is associated with genital and oral cancers.1 Vaccination against HPV is routinely recommended for ages 11–12, yet in 2016 only 49.5% of women and 37.5% of men ages 13–17 had completed the three-dose series.2 Thus, strategies are urgently needed to increase the uptake of HPV vaccination among preteens.

Evidence suggests that many providers are not strongly promoting the vaccine to their patients at the recommended ages.3–7 In addition, many parents are hesitant to decide on HPV vaccination at these ages.7 Engaging preteens in this dialogue can be particularly challenging for parents and providers because it involves discussing how HPV is transmitted (intimate skin-to-skin contact).8 Youth at this age, however, are developmentally positioned to begin making informed decisions about their health and well-being.9–11 Communications strategies that are developmentally tailored and will engage preteens in learning about HPV and the vaccine are warranted.9,12

Serious videogames can be effective at engaging children and adolescents in health decision making.10,13–16 Rather than didactic presentations, serious videogames promote “situated learning” where players can learn through exploration and experimentation. An immersive story is often used to enhance motivation to play the game16,17 and to allow for deeper information processing.15 Further, games that incorporate behavioral theory may be more effective at facilitating health communication and behavior change endpoints.13

Serious games have been used to engage children in a number of health behaviors, including fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity.11,13,18,19 We are not aware of similar research using serious game principles to engage children in decision making about HPV vaccination. Thus, to fill this gap and foster communication and decision making among preteens, we created a serious game whose goal is to increase HPV vaccination knowledge, promote communication with parents and providers, and influence a decision toward initiating the vaccine. The purpose here is to report on the input we received from preteens and parents that helped contribute to the initial development of this videogame.

Materials and Methods

Study context

The videogame is designed to be a part of a larger intervention, Protect Them, to promote HPV vaccination at the recommended ages of 11–12 through enhanced communication among parents, preteens, and providers. Protect Them uses communication tools to normalize a discussion about STIs, cancer, and the benefits of preteen HPV vaccination. Practices and providers receive posters and brochures and online interactive training, whereas parents receive reminder texts for HPV vaccine appointments and web-based information about HPV (see Supplementary Fig. S1 available at http://online.liebertpub.com/doi/suppl/10.1089/g4h.2017.0002). Preteens play a web-based videogame that is designed to gain self-efficacy to participate in the decision-making process. The game is called Land of Secret Gardens and helps preteens learn about the importance of HPV vaccination to keep their bodies healthy as they mature into adulthood.

Theoretical framework

Strategies for developing the game structure and messaging were grounded in theory16,20 and designed to target individual-level determinants21 related to normalizing preteen HPV vaccination. See Table 1 for the categories and codes of constructs used for analyzing discussions with preteens and parents (separately). The game design was informed by the Self-Determination Theory (SDT), which has been applied to other health-promotion games.16 SDT holds that intrinsic motivation for health behavior change is enhanced when a game is entertaining and engaging.16 Thus, the game was designed to be slightly challenging, but entertaining for children in our target range. Game mechanics, such as points and challenges, were also used to increase engagement and repeated play.

Table 1.

Codes for Preteen and Parent Focus Group Discussions

| Coding analysis is based on selected constructs from the Self-Determination Theory (SDT)1–3 and the Health Belief Model4,5. In addition, we have included game elements and gamification components.6 |

| (1) Self-Determination Theory constructs |

| Intrinsic motivation: Doing something because it is inherently interesting or enjoyable, and motivation based in the inherent satisfaction derived from action. |

| Autonomy: A sense of volition or willingness when doing a task. |

| Competence: The ability to do something successfully or efficiently or a need for challenge and feelings of efficacy. |

| Enjoyment: Doing something because one enjoys it. |

| Intentions for future play: Plans to play at least one more time. |

| (2) Health Belief Model |

| Perceived susceptibility to HPV infection: One's opinion of chances of getting a condition. |

| Perceived severity of HPV infection: One's opinion of how serious a condition and its consequences are. |

| Perceived benefits of HPV vaccine: One's belief in the efficacy of the advised action to reduce risk or seriousness of impact. |

| Perceived barriers to getting HPV vaccine: One's opinion of the tangible and psychological costs of the advised action. |

| Cues to action to get vaccinated against HPV: Strategies to activate readiness. |

| Self-efficacy to get vaccinated against HPV: Confidence in one's ability to take action. |

| (5) Knowledge and awareness |

| Info source provider: Private provider or health department. |

| Info source family: Any family member or relative, including a parent. |

| Info source friends: Any friend, peer, or classmate. |

| Info source media: Website, Internet, brochure, poster, or advertisement. |

| (3) Game elements |

| Components may include: Self-representation with avatars; Three dimensional environments; Narrative context (or story); Feedback; Reputations, ranks, and levels; Marketplaces and economies; Competition under rules that are explicit and enforced; Teams; Parallel communication; Systems that can be easily configured; Time pressure. |

| (4) Gamification |

| Components may include: Leaderboards; Levels; Digital rewards (points, badges); Real-world prizes; Competitions; Social or peer pressure. |

| (6) Attitudes and intentions |

| Favorable attitudes: Any response that supports HPV vaccination. |

| Nonfavorable attitudes: Any response that does not support HPV vaccination. |

| Intent to pursue HPV vaccination: The likelihood respondent will get more information about the HPV vaccine or get vaccinated. |

HPV, human papillomavirus.

The development of game messages was informed by the Health Belief Model,20,22 which considers perceptions of susceptibility to HPV infection, severity of HPV-related disease, benefits of vaccination to prevent HPV infection, and possible barriers, including questions of safety, duration, and cost. We also used gain framing23 over loss framing (you can grow up healthy vs. you can get diseases). We base the use of gain framing on other studies24–26 and our own earlier work with middle school students who preferred gain framing when discussing the pros and cons of HPV vaccination.27 See Table 2 for examples of game elements that we incorporated based on our theories and models and those of transportation and story immmersion.28,29

Table 2.

Theoretical Conceptualization and Design of Land of Secret Gardens (LOSG)

| Concept/model | Implementation |

| Autonomy—a construct of intrinsic motivation elaborated on in cognitive evaluation theory; stresses the importance of degrees of choice, and the responsiveness of a game to the player's choices. | LOSG requires players to earn points, however, they can do so by playing one of two games. Players can also choose which plants they wish to purchase at the market, to then use in their gardens. |

| Competence—a construct of intrinsic motivation elaborated on in cognitive evaluation theory; stresses the importance of a player's sense of accomplishment and control over the game. | The incorporation of a leaderboard in LOSG provides a sense of control—to watch progress and orient oneself in the trajectory of the game. Earning points by completing levels in one of two games also contributes to a sense of accomplishment. |

| Presence suggested to be associated with intrinsic motivation; the sense of being within a game. | LOSG incorporates elements of fantasy (i.e.,—a wizard, a faraway land, and elements of mystery). |

| Perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits—components of the Health Belief Model that predict health behavior change; indicators of intention to act preventatively against a negative health outcome. | Ten facts about the prevalence and consequences of HPV, as well as the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine, appear seamlessly throughout play of LOSG. |

| Transportation/Immersion, via the Self-Determination Theory, can allow for intrinsic motivation as players, immersed as characters, have an incentive to finish the story; also stresses value of creating a sense of direct experience to elicit strong responses. | Players are encouraged to complete the game, immersed as they are in a narrative; the game commences with an audio/visual sequence to set up the plot, drawing in players, and emphasizing transportation to a fictional land; though there is not a strong intent to create a direct experience link, the concept of the garden and plant potion are metaphorical, encouraging a symbolic representation of the players as in need of protection also. |

Game development

Researchers used an iterative process to develop the videogame in partnership with professional game developers, Once Upon an App, LLC, Winston Salem, NC, over a 7-month period. The study team included a pediatric clinical psychologist, specialists in public health communication, and a pediatrician. The team refined the game by generating ideas, creating storyboards, beta testing, monitoring, debugging, evaluating, and updating with new insights. The process incorporated preteen and parent input to make the game relevant and acceptable to users while still communicating HPV-related messages. The study was approved by the university's Institutional Review Board.

The intention was to foster (1) in-game autonomy by posing creative choices in planting a thriving garden, (2) in-game competence by challenging the preteen to master the path to planting a healthy garden shielded from disease by a potion (vaccine), (3) narrative presence through an engaging story line of nurturing seedlings when they are young, and (4) motivation to learn about HPV disease and prevention. We use self-determination with both vaccination behavior and game play. To do this, we employed a user-centered approach by recruiting dyads of preteens and parents to provide feedback on game development.

Focus groups

The team conducted three 1-hour focus groups with preteens (11–12 years of age) and two parallel groups with their parents with “time out” in between to enable researchers a longer interval to process the group discussions.30 The focus groups were primarily conducted to improve the user experience by understanding perceptions and motivations for a proposed HPV vaccination game. The purpose of the first discussions was to confirm interest in the game concept and to elicit desired gameplay features. The second focus groups took place 4 months after the first round to review an early version of the game. Questions in the second group explored the use of educational games and also asked for specific feedback on the draft story line, images, and music for the initial mock-up of the garden game. Questions in both the first and second groups focused on knowledge and awareness of preteen vaccines and communication habits. Before intervention launch, the team conducted usability testing with a third focus group with preteens who were asked to bring their device for live play during the discussion time. Table 3 lists the preteen focus group questions and notes whether the questions were asked in the first (December 2014), second (February 2015), or third (May 2015) group. Table 4 lists the parallel parent focus group questions and notes that questions were asked in both the first (December 2014) and second (February 2015) groups. Through the course of the discussion, the facilitator encouraged participants to share if they had similar or different opinions from those that were discussed by other participants.

Table 3.

Questions for Preteen Focus Group Discussions

| Gaming interests and practices (focus groups 1 and 2) |

| 1. What videogames do you like to play? |

| 2. What do you like about the games? |

| 3. What makes the game fun: getting points or getting to the next level? |

| 4. If you were to develop a game for your friends, what would you put in that game? |

| 5. Do you communicate, or have conversations with other people in the game? |

| 6. Do you know the other players? |

| 7. What devices do you use to play (pc, mac, tablet, phone)? |

| Games with an educational message (focus groups 1 and 2) |

| 8. What comes to mind when you think about educational games? |

| 9. What kind of experience, if any, have you had playing educational games? |

| 10. What did you like about the educational games you have played? |

| 11. If you wanted to develop a game to teach your friends about healthy eating, or health, or a vaccine, what would you think about a game like that? |

| 12. If there was a game like that, that taught about HPV vaccination, is that something you would play with your parents? |

| 13. If your parents gave you a game and said, “Look, check out this game. It's something to learn about the HPV, about the vaccines that you're getting at this age,” would that be something that you'd be interested in? |

| 14. What in the game would help you understand about the vaccine? |

| 15. What is some information about the HPV vaccination that you would like to see in the game? |

| 16. What kind of information would make you feel like you could trust that information? |

| 17. Even if the information was being played in a game, would you think that it would be still trustworthy, if it came from a trustworthy source? |

| 18. What do you think your friends want to know about HPV? |

| Knowledge and awareness of preteen vaccines (focus groups 1 and 2) |

| 19. What do you know about vaccines for your age 11–12? |

| 20. What have you heard about the HPV vaccine? |

| 21. Has anyone ever heard of the HPV vaccine before today? |

| Where or from whom have you heard about the HPV vaccine? |

| 22. Have you heard of HPV before today? |

| What have you heard about it? |

| 23. What would make you want to get the vaccine? |

| 24. What would keep you from getting it? |

| 25. What would you want to know most about the virus or vaccine to help you make a decision about getting it? |

| Communication |

| 26. Do your mom/dad ask your opinion about shots or other medical/health decisions, or do they just make the decision for you? |

| 27. Ideally, how would you like to make decisions about your health with your parents? |

| 28. Is there anything that would make it easier? |

| 29. How does your doctor talk with you about your health? |

| Does s/he talk directly with you? |

| Does your parent leave the room? |

| Do you feel comfortable talking with your doctor about anything? |

| 30. If you wanted more information about something related to your health, where would you go to get it? |

| What about advice? |

| 31. If you wanted to learn more about vaccines, how would you do that? |

| 32. How many of you have cell phones? |

| Do you text on your phone? |

| Would you be interested in getting health-related texts on your phone from your doctor's office? |

| What about HPV-related texts? |

| What about reminders to go to your doctor's appointment? |

| 33. What are your thoughts about these messages?: |

| “HPV is a sexually transmitted infection. But there is a vaccine you can get to prevent it!” |

| “If you get the HPV vaccine, it will keep you healthy.” |

| “You need to get the HPV vaccine to keep from getting HPV one day.” |

| Feedback on game concept (focus groups 1 and 2) |

| 34. Creative exercise: If you were to text a message to a friend about HPV vaccination, what would you say? |

| 35. Use your imagination about what this opening scene for our game would look like: “Long ago and far away a land was filled with secret gardens. Now they're gone and no-one knows why…you can find them if you try…the secrets you discover there will help you throughout life…” What do you think this would look like? |

| 36. What would you put in this secret garden? You said magic would be good to have in it? |

| 37. What do you think the garden wizard does in the game? |

| 38. Let's see what you think about this music… |

| Feedback on specifics of the Land of Secret Gardens (focus group 3) |

| 39. What are your overall impressions of the game? |

| 40. How easy/difficult was it to grasp the concept of the game? |

| 41. Did you need any help playing the game, and if so, who provided it? |

| 42. How much effort did you put into playing the game? |

| 43. How much control over the game did you feel that you had? |

| 44. How easily were you distracted or interrupted while playing? |

| 45. What did you learn from the game? |

| 46. What, if anything, made the game fun or interesting to you? |

| 47. What did you like most/least about the game? |

| 48. Were there any activities that were kind of boring? |

| 49. What would you like to change about the game if you could? |

| 50. What did you learn from playing the game that you did not know before you played it? |

| 51. What other things did you want to learn? |

| 52. Did the game evoke any emotions, such as concern, anger, or confusion, and if so, how did you handle them? |

| 53. How motivated would you be to continue to play this game? |

| 54. About how much time would you spend playing? (looking for minutes/hours) |

| 55. How likely would you be to recommend this game to a friend? |

| 56. What can you tell me about the potion? |

| 57. What did it explain to you about how a potion is made? |

| 58. What did you think about the pop-up messages? |

| 59. Did the pop-up messages take you out of the experience of the game? |

| 60. How easy/difficult was it to get to the next screen or find the hidden object in the game? |

| 61. Did you think that the rewards were fair for what you were trying to do? |

| 62. Did you feel like when you were playing the game your performance was being measured correctly? |

| 63. Earlier, I asked a little bit about emotion and you said it's kind of scary because there's a creepy gnome guy. Was it scary also because there was information about HPV? |

| 64. Would you mind talking to your parents about the game or what the game is about? |

| 65. Is there anything else about the game that you think we should know? |

Table 4.

Questions for Parents' Focus Group Discussions

| Information sources for vaccination |

| 1. Where do you usually get information about the 4 vaccines (Tdap, Meningococcal, Flu, and HPV) that are required or recommended for your preteens? |

| 2. How or why are these sources helpful to you? |

| 3. How could these sources be more helpful to you? |

| 4. What kind of information would be helpful to parents like yourself to vaccinate your son or daughter at age 11 or 12 for the HPV vaccine? |

| 5. How do you think parents would like to get that information? |

| 6. What have you heard parents say about HPV vaccination of their children? |

| 7. What have you heard doctors or nurses say about HPV vaccination? |

| Motivators for/against vaccination |

| 8. What are some reasons you would get your preteen vaccinated against HPV? |

| 9. What are some of the reasons you would NOT get your preteen vaccinated against HPV? |

| 10. Is there anything else that would motivate you to vaccinate your son or daughter? |

| Discussing health-related topics |

| 11. Have you ever talked with your son/daughter about any of the preteen vaccines? |

| Which ones? |

| What brought up the conversation? |

| How did the conversation(s) go? |

| 12. Have you talked with your son/daughter about the HPV vaccine? |

| How did that conversation go? |

| Did you prepare in any way beforehand? |

| Starting a conversation |

| 13. Is there anything that you would have liked but didn't have to start the conversation with your preteen? |

| 14. If you haven't talked with them, why not? (or why do you think parents might wait to talk or not talk at all) |

| Feedback on project development |

| 15. Last year, parents said that conversations with a healthcare provider, brochures, and a website were the most preferred ways to learn about the vaccine. Does that seem about right to you? |

| 16. What would you want to see on a website? |

| What sort of information? |

| How would you like to see it? |

| 17. What do you think about the look and navigation of this sample home page? |

| 18. What do you think about this proposed content? |

| 19. How acceptable would it be to have information about these topics on the website?: |

| Risk of getting HPV over a lifetime |

| Transmission |

| Health outcomes |

| Symptoms |

| Why vaccinating at 11–12 is important (or before sexual debut) |

| 20. Should we include any of these preteen topics on the website, in addition to the HPV vaccine? |

| All preteen vaccines |

| Puberty and what that means to parenting, your family, and relationship with your child |

| Other common health/social concerns such as depression, substance use, smoking |

| -How to start the conversation about sex |

| -More in-depth information about sex |

| 21. What would you think about a short 30-second video from kids and parents about vaccination? |

| Would that help you make a decision about vaccination? |

| Is there something you'd like to see covered in a video? |

| 22. How would you react to text messages from your healthcare provider about?: |

| Appointment reminders |

| Short motivational messages such as “Protect Them” |

| Links to other pieces of our project, such as the website or the videogame |

| 23. What are your thoughts about why you might NOT want to get texts? |

| How often would you want to get texts? |

| How much is too much? |

| Feedback on videogames |

| 24. First, what do you think about the idea of using a videogame to teach about preteen vaccines? |

| 25. Would you prefer it focus on preteen vaccines in general, or on HPV vaccine only? |

| 26. Any other thoughts about how to “package” the message? |

| 27. Would you be willing or interested in playing a vaccine game with your child? |

| It could be for fun, or as a way to start a conversation around HPV vaccine or (broader) |

| 28. Any preferences on competitive vs. cooperative themes? |

| 29. Do you play videogames with your preteen now? |

| What do you like about it? |

| What don't you like? |

| 30. What types of information or messages would you most like to see in a videogame? |

| 31. Did we miss any good ways to communicate with you or with your preteens? |

| 32. How much control/interaction would you want over what your kids see from our project? |

Questions same for both groups of parents.

Data analysis

We conducted thematic analysis by constant comparison, a technique in grounded theory through which codes and categories are defined.30 The team compiled a list of codes used in past research to develop discussion guides for the preteen (Table 3) and parent (Table 4) focus groups. The team worked together to have consistency in coding but did not test intercoder reliability since operational definitions seemed to be clear. Past research was based on constructs from the Self-Determination Theory,16 the Health Belief Model,20 gamification,13 and HPV vaccine decision making.31,32 All focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three authors independently reviewed transcripts, marked passages according to the categories and codes, and identified exemplar quotes.

Results

Game structure

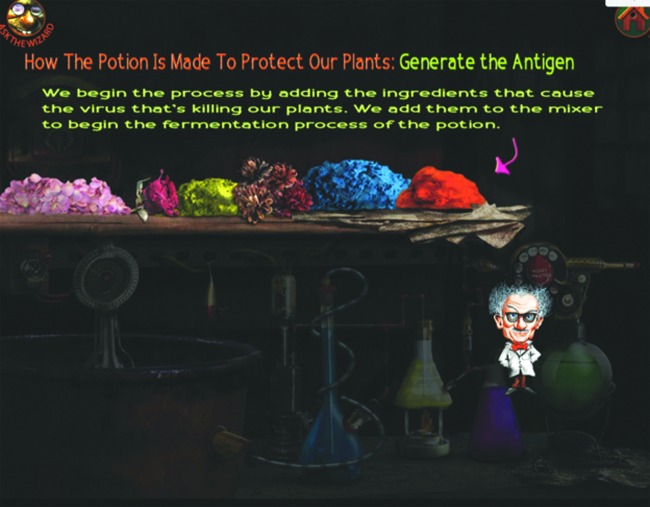

The Land of Secret Gardens is a single-player videogame and is designed for repeated play on tablets, smartphones, and personal computers by 11–12-year-old boys and girls with IOS or android operating systems (Table 5). The first scene with a garden shows planting beds without plants (Fig. 1). Preteens play interactive “mini-games,” which pull them into the game by teaching them to protect their bodies—or “secret gardens”—from HPV through vaccination. The mini-games include several versions of “Find the Hidden Objects in the Garden Shed,” (Fig. 2) and a motion game in which falling HPV viruses can be zapped before they hit flowering plants below (Fig. 3). Coins are earned for completing the mini-games, allowing the preteen to purchase supplies for planting seeds in their garden (Fig. 4). As more coins are earned, players can create a potion—or vaccine—to protect their plants from diseases—or HPV (Fig. 5). Successful protection ultimately results in mature plants being covered by shields (Fig. 6). The design includes gamification features with rewards and levels, and it excludes elements of competition and peer pressure. Players learn facts about HPV and the benefits of vaccination via messages that briefly flash on screen without interrupting play (Table 6).

Table 5.

Characteristics of a Videogame for Health: Land of Secret Gardens

| Health topic(s) | HPV vaccination |

| Targeted age group(s) | 11–12 years of age |

| Other targeted group characteristics | Boys and girls |

| Short description of game idea | The game is designed to entertain children so that they are more receptive to learning about HPV and the benefits of vaccination. |

| Target player | Individual |

| Guiding knowledge or behavior change theory(ies), models, or conceptual framework(s) | Health Belief Model; Self-Determination Theory |

| Intended health behavior changes | Decisional balance; communication |

| Knowledge element(s) to be learned | Facts about HPV and HPV vaccination; Dispelling myths about how vaccines are made |

| Behavior change procedure(s) (taken from Michie inventory) or therapeutic procedure(s) employed | Information about general and individual consequences; normative information about others' behavior; anticipate future rewards |

| Clinical or parental support needed? (please specify) | Parents can play with child as an observer but not required |

| Data shared with parent or clinician | No |

| Type of game: (check all that apply) | Strategy; Casual Play; Educational |

| Story (if any) | |

| Synopsis (including story arc) | A back-story about a secret garden was developed as a metaphor for a preteen's body and keeping it healthy. The goal is to plant a lush secret garden and protect the seedlings by treating them when they sprout with a potion to keep them healthy as they mature. Points to buy seeds and create the potion are earned by playing mini-games. Throughout the process of play, players are exposed to messaging about HPV and the benefits of the vaccine. |

| How the story relates to targeted behavior change | Land of Secret Gardens is a metaphor about keeping oneself healthy by vaccination against viruses that can cause infection and disease |

| Game components | |

| Player's game goal/objective(s) | Level up by planting and tending to a flourishing secret garden—protect the seedlings before they mature. |

| Rules | Players must earn points by playing mini-games to purchase seeds for their garden and ingredients to create a vaccine to protect seedlings. Embedded within the game are HPV messages. Points earned in the game are exchanged for seeds and ingredients to create a vaccine. |

| Game mechanic(s) | Feedback loops; encourage discovery/exploration; resource management; levels; points; badges |

| Procedures to generalize or transfer what's learned in the game to outside the game | Players are encouraged to discuss the game with their parents |

| Virtual environment | |

| Setting (describe) | Third-Person Point of View |

| Avatar | |

| Characteristics | Static cartoon picture |

| Abilities | None |

| Game platform(s) needed to play the game | Smartphone, tablet, computer |

| Sensors used | Touch and keypad |

| Estimated play time | Unlimited; players can keep playing until they are satisfied with their garden. |

FIG. 1.

Screenshot: Garden at beginning.

FIG. 2.

Screenshot: Earn points by finding hidden objects.

FIG. 3.

Screenshot: Earn points with the shield power game.

FIG. 4.

Screenshot: Garden with new plants.

FIG. 5.

Screenshot: Making the potion.

FIG. 6.

Screenshot: Garden with shielded adult plants.

Table 6.

Game Messages About Human Papillomavirus and Human Papillomavirus Vaccine

| HPV stands for HPV. |

| HPV can cause genital warts. |

| HPV can cause certain cancers. |

| HPV can be transmitted to another person through sexual contact. |

| Most people get HPV at some point in their lives. |

| HPV can be prevented by a vaccine. |

| HPV vaccination is recommended for both boys and girls at ages 11–12. |

| HPV vaccine is safe. |

| HPV vaccine is effective. |

| HPV vaccine can be given at the same time as other recommended vaccines. |

Focus groups

Overall, 16 preteens, ages 11 and 12, participated in the three rounds of focus groups. Of the 16, 11 were boys, 5 girls, 7 white, 8 black, and 1 of mixed race. Five boys, two girls, and seven mothers participated in the first round to discuss the game concept and desired gameplay features. The second focus group with two preteen boys and their mothers took place 4 months after the first round to review an early version of the game. Usability testing was conducted with a focus group of four boys and three girls.

Preteen participants responded more to the moderator-guided questions than to each other's responses. Participants in the usability group were more talkative than in the preceding two, sometimes cutting each other off and empathizing with common likes and dislikes while playing the game. Parent participants responded voluntarily, often providing anecdotes or extended responses that solicited verbal agreement from others in the group.

From the focus groups with preteens (Table 3) and their parents (Table 4), we identified five thematic groups: (1) knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination, (2) attitudes and intentions to get vaccinated, (3) features of the Health Belief Model, (4) self-determination of preteens, and (5) preferred elements of gamification. Exemplar quotes are in Tables 7 and 8.

Table 7.

Preteen Focus Group Themes For Game Development

| Themes | Patterns within themes | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and awareness | Info source provider Info source family Info source media Info source school Info source undefined |

“I want to know about the symptoms and the signs of how you get—like the signs, or how do you know you got the virus, like headaches or anything like that, I'd want to know.” “My mom knows about it because she read the little paper.” “I was going to get it but the doctors said something about side effects.” “[My PE teacher] he says…when you're trying to avoid HPV, when someone has it, you try to avoid…contact, touching them or like either talking to them…and like some places that are like infected with diseases stay away from there…” “Viruses, they're a type of bacteria that gets inside your body from—through your nose, if you breathe it in, taste it, or it goes through your mouth, or it can enter either into your skin and…once it starts it spreads throughout your body and makes you sick…” |

| Attitudes and intentions | Favorable Nonfavorable Intentions to get vaccine |

“Because I've heard on the news that vaccines and stuff like that, they cause retardation and stuff. It makes your brain stop functioning” “[My mom] will say something like if you get HPV and it's at the future, she will say something like we need to get the vaccine before you get that type of virus.” “I would get the vaccine so I can stay safe and healthy in the future.” |

| Health Belief Model | Perceived susceptibility Perceived severity Perceived benefits Perceived barriers Cues to action Self-efficacy |

“If you don't have it, then you could get a certain virus. And if you do have it, you can't get those viruses.” “So that way when it breaks out you're already cleared, that you can go back to school, get your education…” “I would like to know more about it. Because if I don't know a lot about it then I won't get the shot. I'm not really comfortable around shots…” “I'm still scared of needles.” “I would create have you ever heard of HPV? And if they say yes or no I would say, well it's a very bad virus, it only happens when you have skin contact or sexual contact. And then if other person says, like really, or something like that, I would've said, yeah, man, it's a virus and it can do very bad things to you…” “HPV is like not good.” “Maybe it should have the information that would like—your parents should send you the information for the last time they got their vaccine shot, so that way you can predict around the time that you should get another one so you could send a text like, for example, that you have to get a vaccine shot in maybe like five days or something like that.” “I feel like the point of HPV [the vaccine] is that you can protect yourself…” |

| Self-determination | Transportation Autonomy Competence Intrinsic motivation Enjoyment Intentions for future play |

“See, I'm into cars, so I'm a racing car game fan…I like the thrill, cause you know, when the cut scene comes on, you walk past the corner or somebody can be shooting at you, the vibration of the controller, the shot just feel your whole body…Like I actually felt it before, the shock of the controller just travels all through you, you just feel like jumping up…” “Those really pulled me in…it was like they were really magical…” “I like how you didn't tell us what to do but you made us figure it out” “It's like okay, play this game for homework and we're all just like oh yeah, I've already played it. I'm a pro.” “The thing that I saw is I didn't have to get all the items to finish and it said now you have a score. I was like oh I want to keep going.” “But then with the other one, the mystery one, I think that one was kind of easy to figure out oh, like find this, find this.” “I mean when I first heard about this game, my dad said, “hey do you want to do this game for this focus group?” I was like oh he's probably just tricking me and it's going to be one of those like question and answer quiz things but once I logged on and I saw just a fun page of it, I realized it was going to be nothing like that and it wasn't/It was a really fun, educational game.” “I'd play it every day if I had a choice…” “I want to be the first one to play it.” “But like it's like two games. It's the find one, the finding stuff and then like the shield game. I mean it showed you like facts about the virus… and then it was fun but then like with the garden and everything that was really fun. You can plant stuff. I liked how they incorporated the virus kind of too in some of the mini games like the one with the shield game, like the blue ones.” |

| Game elements/gamification | “…I mean you start out with the plants in the store but as you get like more and more points and plant more, you get like a bigger garden. You can upgrade your garden and get more, buy more plants with like points…buy more items for your garden, make other potions” “Honestly, it's kind of fun though…because the game is kind of set in a magical place because there's the creepy little wizard, gnome guy and gnomes just period…but like ones with eyes and a smile and sharp teeth and then like the music kind of goes with that…” “That's what kind of brings me some ideas about your game. What I think you should do is be like different types, like different types of different magic. I think there should be lots of magic with your game, like the opening cut scene…” “I'd play it with my parents, but most likely I wouldn't play it if one of my friends would come over…. Because they could make fun of me… Ha-ha; you're looking at and playing a game about health. Some people do that at school.” |

Table 8.

Parent Focus Group Themes For Game Development

| Themes | Patterns within these themes | Exemplar quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge and awareness | Info source provider Info source family Info source media Info source school Info source undefined |

“And sometimes our kids are more apt to talk to someone else than talk to us…because sometimes it takes a second person” “In light of that, you also have to think of with children, some of their information does get across to them through education, through games” “That's what I want; I don't want them (my children) to ever be scared to come to me” “As parents, you know, we need to be that first line to put the information out there…” “So sometimes we have to take our experience and what we know and share with other parents and I think that will make it easier to some of them, even if they're kind of squeamish” “I mean, I trust them, so they're doctors…So I would feel confident in his decision…You know, you're trusting your physician…” “And I think if they (the provider) recommend it (the HPV vaccine) and you still decide you're not going to do it that day, they should do a follow up, like a call…I see these people really recommending it…” “And I think it helps if that provider, they have kids, they can say, well you know what, I have three, and I understand, and I made the decision…” “The age group it recommended for, how often it needs to be given, the ingredients, the percentage wise of effectiveness, and the cons of it, the negative” |

| Attitudes and intentions | Favorable Nonfavorable Intentions to get vaccine |

“I said, so at least this way you're protected. And he (my son) was like, whatever I can to protect myself” “…the only time they (the provider) mention it is when you're going to get shots, they mention it on that day and you're like hello, it's the day of, no” “I would just say that when they (children) do become sexually active they're already protected, if they get the vaccine at an early age” “They (hesitant parents) use that as like a stepping stone instead of saying, I'm not ready to talk about it yet with their kids” “…but if it's beneficial in the long term, then yes, I would consider it, but you know, it's like I'm against the chicken pox vaccination, I'm one of those parents that believe you should still get chicken pox the natural way” “I think for a lot people what it is when you start hearing vaccination people, you get paranoid like, okay, what is this combination of stuff that you're saying we need to fight, and how will this affect me in the long term because of course there's that whole vaccination cause autism. Once people get in that frame of mind, there's no changing their mind” “You definitely want to know side effects because again, you're introducing the body to a foreign agent that is not used to, and like she said, with viruses constantly changing, every time it changes is because somebody's DNA put their own little stamp on it which made that change so then it's back to the drawing board. Let's figure out a new cocktail” “Again it's the whole weight of considering what cocktail of stuff you want to be putting in my baby to prevent something down the line” “…if the information is just backed up with just a little more benefit and not just this is what your child needs, and this is why, and you know, had it not been presented the way that it was presented, then I would be one of those parents who was like, okay, yes, this would be for your own protection…” “Yes, especially with everything always changing, you definitely want to know your rights, and if there's an opt out, things of that nature” “Well I've heard a couple of my co-workers, well, it seems like they're just pushing it toward the African American community, like it's our children that are the only ones out there having sex” “I think that where things, where kids act out a lot of stuff, what's not being done is it's being talked about so if you talk about it, you take the stigmatism off of it” |

| Health Belief Model | Perceived susceptibility Perceived severity Perceived benefits Perceived barriers Cues to action Self-efficacy |

“I have all boys, and the things that I saw were mostly based toward girls” “So, when you, you know, the reason why it's in our minds like that is because that's how it's associated. Get this for your child because they are sexually active” “Well, let's just put it like this. Every few years there's going to be something new” “And that's even if it's preventable because you can still vaccinate and still get it” “So when he found out about HPV, I talked to him about it, you know, that's not saying that you want to go there and do anything, but you can be an adult and sleep with somebody for the first time and she can have it” “…it just seems like you just trying to vaccinate against sexually transmitted diseases which is impossible because people carry germs, and you got to build up an immunity to even fight something first” |

| Self determination | Transportation Autonomy Competence Intrinsic motivation Enjoyment Intentions for future play Conversations |

“No, they (the preteens/children) need to have some type of input on what's taking place.” “…as a parent, you're not going to take that decision away from me at the visit saying this is what they need. No, this is what you're saying that they need” “It just that with that age comes more responsibility of individual decision thinking” “Well, the first thing that we do is I tell him, I say, since the world is full of information and it's accessible, let's get on the Internet to see what viable sources we can get it from” “You come tell me what you've learned, and then we discuss it together” “…the average parent, not going to really have the time to sit there and look at a video, and then be like, I don't need no video to talk, how to talk to my child” “Games are not real, but diseases are real. So it just needs to be presented to them as this is real” |

| Game elements/gamification | “Like a little time limit that is going to keep their attention long enough and still give them the amount of information that they need” “It's not going to work…it's because based off of the type of games that they are playing now and the graphics and everything they're already exposed to,—so if you want to get some information to them, you got to put a little shooting or something…” “…put it something similar to that, and you know, keep the same thing where you're rebuilding, you're earning points based off how much information you know, that's definitely going to be a winner to get them to play” “Something to keep them going, so if they don't pass it and they come back the next day, they try to pass it again, so they go up another level.” |

Knowledge and awareness of HPV and HPV vaccination

Both preteens and their parents shared the desire to know about HPV transmission, how to avoid the virus, and whether HPV vaccination was safe. Parents wanted to have a trustworthy source for preteens to consult and they were acutely aware that sources other than parents themselves were often helpful.

Attitudes and intentions to get vaccinated

Preteens wanted to be able to protect themselves against the virus and “be safe and healthy in the future.” Parents were mostly favorable about HPV vaccination but also acknowledged that some parents were hesitant and wanted more time to decide.

Features of the Health Belief Model

Preteens recognized their risk of getting HPV and also admitted their dislike of shots. Parents tended to accept preteen HPV vaccination but also wondered whether additional infectious diseases would require vaccination in the future.

Self-determination of preteens

Preteens said that they would play the game with parents but not with friends because of the sensitive STI topic. Parents seemed eager to have their children learn the facts, noting that “with age comes more responsibility of individual decision making.”

Preferred elements of gamification

Preteens preferred a videogame that was both entertaining and instructional, that provided an opportunity to earn tokens, and that offered advancing levels. They liked the garden concept, the “spooky” music and were interested in facts about HPV. Parents also favored levels that were contingent on correct answers to HPV knowledge questions. Some parents expressed hesitancy around games as motivational tools (“games are not real, diseases are real”). The game is currently in a research study funded by the National Institutes of Health to determine whether it is effective in stimulating preteen/parent/provider conversations and decision making about HPV vaccination. The game is not publicly available while used in the study.

Discussion

This article reports on the development of a videogame about HPV and the importance of HPV vaccination targeted for preteens ages 11–12. We based the design concept on theoretical constructs from the Health Belief Model of assessing personal risk of getting an STI or cancer and on the Self-Determination Theory, which emphasized autonomy and competence in health decision making. We used an engaging story line to plant a thriving garden and drop-down facts about HPV disease and prevention to educate about HPV and consequences of the virus. Our game is part of an intervention in clinical settings that is used to motivate the acceptance of HPV vaccination by providers, parents, and preteens. The formative work led to a gain-framed game metaphor for one's own body and a potentially effective narrative to promote HPV vaccination to young adolescents. This is the first demonstration of the use of serious videogames targeted toward preteens to promote HPV vaccination uptake.

There is promise in using serious videogames to facilitate promotion of healthy lifestyles,13,33,34 but there has been very little work on using serious videogames to address vaccine hesitancy.11 A recent review found 16 videogames related to vaccination developed since 2003 (none targeted HPV).35 The authors concluded that such approaches could be a useful public health tool to address vaccination hesitancy, but that there is still a need to incorporate behavioral theories in their development and evaluate their targeted objectives. In general, interventions to increase vaccine uptake perform better when they include multicomponent communication strategies and/or have a focus on dialogue-based approaches.35 Thus, one of our goals in developing Land of Secret Gardens was to use the behavioral theory to inform the design of a game that could fit into a larger communication intervention aimed at increasing HPV vaccination uptake. We also aimed at developing a game that could be useful in not only increasing awareness of the vaccine and decreasing stigma, but that could also be used to stimulate dialogue with parents and providers. In the future, we will evaluate the extent to which preteens playing this game affected HPV vaccination attitudes, increased communication, or motivated vaccination uptake.

The qualitative data collection allowed us to refine our approaches before developing the software for the game. Data from our focus groups showed that 11–12-year-olds were very willing to discuss their knowledge or lack of knowledge regarding HPV and the vaccination. This suggested to us that appropriately presented information about HPV and how it is contracted and prevented, as in Land of Secret Gardens, has the potential to incite curiosity and a desire for conversation in these preteens. Parents acknowledged a hesitancy to discuss STIs with children at this age, and the importance of reliable information sources and recommendations for or against vaccination. They confirmed the value of providers' opinions and a wariness of side effects and ineffectiveness, and they responded well to the idea of protecting their children from harm. Though we received mixed responses from parents as to whether games can be a serious vehicle to communicate about STIs and vaccination, they provided insight for improvement to address this concern. Land of Secret Gardens strives to be an effective and unique intersection to encourage discussion around controversial health topics—vaccination and STIs—as well as provides an engaging source of information. The feedback received from these focus groups is novel in providing insight to this end.

Of note, the approach we used for game development had both strengths and limitations. A strength of our development approach was the involvement of both preteens and their parents in helping to guide the design of the videogame. This was helpful because it allowed our team to test different game concepts, imagery, sound design, and text that could be integrated in the game in a manner relevant to children who are in the targeted age range for vaccination. Having parents provide feedback was also helpful to the development process as they provided insight into the types of games their children play and the degree to which they would engage with a serious game. This type of collaborative design is useful for developing games that will appeal to the target audience. Our development process was also informed by the health behavioral theory, which has been shown to result in better outcomes.20,22

A potential limitation of our approach was that only three focus groups with preteens and two with parents were conducted and each group formed a separate sample for a separate purpose. This limited our qualitative analysis because we could not reach a saturation level of data collection, and we are unable to fully integrate these qualitative findings from the various focus groups to better understand the underlying constructs being evaluated. However, this did allow for a more rapid and fluid development process that was essential to meet the timeline for the development of other intervention components. Another limitation is that that we did not conduct an intercoder reliability test to check consistency among the three coders. However, codes were developed based on published research,16,20,22,26,28 the coders received training in the coding methodology, and constant comparison methods were used whereby the coders reviewed and resolved any coding discrepancies. Together, these methods are helpful in producing more reliable results.30 Again, although this potentially limits the overall validity of the qualitative findings, it did allow for the team to quickly assess the content being developed for the game.

Conclusion

Our formative research with preteens and their parents indicates that a serious videogame is a potentially effective channel to promote HPV vaccination communication and uptake. The key element is fostering preteen self-efficacy so that the preteen feels empowered to question an adult (parent or provider) about a sensitive sexual health subject (STI and vaccine). The game is intended to foster conversation with a parent in the context of a metaphor about growing up and taking care of a garden (self) so that it is healthy and protected from viruses. The next phase is to test the game in clinical settings and with preteens and parents assigned to comparison intervention and control groups. Outcomes to be measured include preteens' perceived self-efficacy to communicate with parents and providers about HPV vaccination.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Randall Teal, UNC's CHAI Core and Regina McNeill Johnson for assistance with participant recruitment. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health 1R01AI113305-01 J.R.C. (PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) recommendations and reports. MMWR 2014; 63(RR05):1–30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Singleton JA, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:874–882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holman DM, Benard V, Roland KB, et al. Barriers to human papillomavirus vaccination among us adolescents: A systematic review of the literature. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168:76–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents, 2007–2013, and postlicensure vaccine safety monitoring, 2006–2014—United States. MMWR 2014; 63:620–624 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofstetter AM, Rosenthal SL. Health care professional communication about STI vaccines with adolescents and parents. Vaccine 2014; 32:1616–1623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hofstetter AM, Stockwell MS, Al-Husayni N, et al. HPV vaccination: Are we initiating too late? Vaccine 2014; 32:1939–1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mergler MJ, Omer SB, Pan WKY, et al. Association of vaccine-related attitudes and beliefs between parents and health care providers. Vaccine 2013; 31:4591–4595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is HPV? HPV home. 2017. www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/whatishpv.html (accessed August15, 2017)

- 9.Ford CA, Davenport AF, Meier A, McRee A-L. Partnerships between parents and health care professionals to improve adolescent health. J Adolesc Health 2011; 49:53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson D, Baranowski T, Buday R. Conceptual model for the design of a serious video game promoting self-management among youth with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2010;4:744–749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baranowski T, Thompson D, Buday R, et al. Design of video games for children's diet and physical activity behavior change. Int J Comput Sci Sport 2014; 9:3–17 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chu SKW, Kwan AC, Reynolds R, et al. Promoting sex education among teenagers through an interactive game: Reasons for success and implications. Games Health J 2015; 4:168–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson D, Baranowski T, Buday R, et al. Serious video games for health how behavioral science guided the development of a serious video game. Simul Gaming 2010; 41:587–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu AS, Baranowski J, Islam N, Baranowski T. How to engage children in self-administered dietary assessment programmes. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014; 27:5–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baranowski T, Buday R, Thompson DI, Baranowski J. Playing for real: Video games and stories for health-related behavior change. Am J Prev Med 2008; 34:74–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryan RM, Rigby CS, Przybylski A. The motivational pull of video games: A self-determination theory approach. Motiv Emot 2006; 30:344–360 [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGonigal J. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Press; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barnett A, Cerlin E, Baranowski T. Active video games for youth; A systematic review. J Phys Act Health 2011; 8:724–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson D, Bhatt R, Lazarus M, et al. A serious video game to increase fruit and vegetable consumption among elementary aged youth (Squire's Quest! II): Rationale, design, and methods. JMIR Res Protoc 2012; 1:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becker MH. The Health Belief Model and Personal Health Behavior. Health Education Monographs. Vol Monog. 2. San Francisco, CA: Society for Public Health Education; 1974:324–508 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartholomew LK, Mullen PD. Five roles for using theory and evidence in the design and testing of behavior change interventions. J Public Health Dent 2011; 71:S20–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Lewis FM, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002:45–66 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothman AJ, Bartels RD, Wlaschin J, Salovey P. The strategic use of gain- and loss-framed messages to promote healthy behavior: How theory can inform practice. J Commun 2006; 56:S202–S220 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang Y, Cho H, Sands L, Jeong SH. Effects of gain- and loss-framed messages on the sun safety behavior of adolescents: The moderating role of risk perceptions. J Health Psychol 2012; 17:929–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nan X. Relative persuasiveness of gain- versus loss-framed human papillomavirus vaccination messages for the present- and future-minded. Hum Commun Res 2012; 38:72–94 [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Keefe DJ, Jensen JD. The relative persuasiveness of gain-framed and loss-framed messages for encouraging disease detection behaviors: A meta-analytic review. J Commun 2009; 59:296–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cates JR, Ortiz RR, North S, et al. Partnering with middle school students to design text messages about HPV vaccination. Health Promot Pract 2015; 16:244–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green MC, Brock TC. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000; 79:701–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu AS, Baranowski T, Thompson D, Buday R. Story immersion of videogames for youth health promotion: A review of literature. Games Health J 2012; 1:199–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindlof TR, Taylor BC. Qualitative Communication Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011:243–249 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reiter PL, McRee A-L, Pepper JK, et al. Longitudinal predictors of human papillomavirus vaccination among a national sample of adolescent males. Am J Public Health 2013; 103:1419–1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shafer A, Cates JR, Diehl S, Hartmann M. Asking mom: Formative research for an HPV vaccine campaign targeting mothers of adolescent girls. J Health Commun 2011; 16:988–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Thompson D, Buday R. Behavioral science in video games for children's diet and physical activity change: Key research needs. J Diabetes Sci Technol 2011; 5:229–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baranowski T, Baranowski J, Thompson D, et al. Video game play, child diet, and physical activity behavior change a randomized clinical trial. Am J Prev Med 2011; 40:33–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohannessian R, Yaghobian S, Verger P, Vanhems P. A systematic review of serious video games used for vaccination. Vaccine 2016; 34:4478–4483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.