Abstract

Objective

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a genetically complex, inflammatory bile duct disease of largely unknown aetiology often leading to liver transplantation or death. Little is known about the genetic contribution to the severity and progression of PSC. The aim of this study is to identify genetic variants associated with PSC disease progression and development of complications.

Design

We collected standardised PSC subphenotypes in a large cohort of 3402 patients with PSC. After quality control, we combined 130 422 single nucleotide polymorphisms of all patients—obtained using the Illumina immunochip—with their disease subphenotypes. Using logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards models, we identified genetic variants associated with binary and time-to-event PSC subphenotypes.

Results

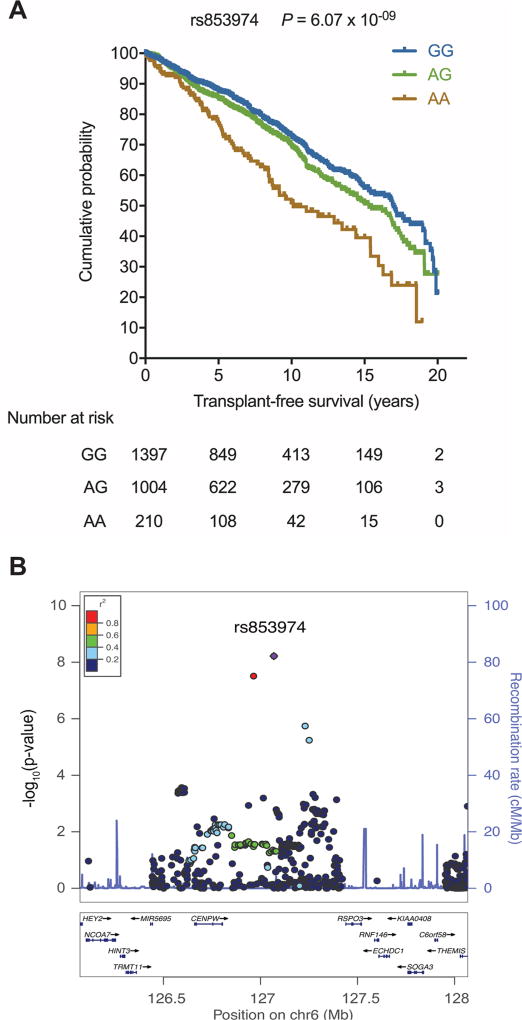

We identified genetic variant rs853974 to be associated with liver transplant-free survival (p=6.07×10−9). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a 50.9% (95% CI 41.5% to 59.5%) transplant-free survival for homozygous AA allele carriers of rs853974 compared with 72.8% (95% CI 69.6% to 75.7%) for GG carriers at 10 years after PSC diagnosis. For the candidate gene in the region, RSPO3, we demonstrated expression in key liver-resident effector cells, such as human and murine cholangiocytes and human hepatic stellate cells.

Conclusion

We present a large international PSC cohort, and report genetic loci associated with PSC disease progression. For liver transplant-free survival, we identified a genome-wide significant signal and demonstrated expression of the candidate gene RSPO3 in key liver-resident effector cells. This warrants further assessments of the role of this potential key PSC modifier gene.

Introduction

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a complex, cholestatic liver disease, in which chronic biliary inflammation and bile duct destruction leads to biliary fibrosis and liver cirrhosis, often in a slowly progressive manner.1 PSC is characterised by a cholangiographic image of strictures interchanged with dilatations throughout the biliary tract. Reported incidence rates of PSC vary widely, with incidence rates of 0.91, 1.31 and 0.5 per 100 000 inhabitants per year for North America, Norway and the Netherlands, respectively.2,3 There is a male to female ratio of 2:1, and the disease can occur at any age, with a peak incidence around 40 years.3 There is a close association between PSC and IBD, and PSC patients are subject to a fivefold increased risk of developing colorectal carcinoma (CRC) when compared with the general population.3 In addition, PSC carries an excess risk of cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) which seems to be unrelated to the disease duration and the presence of liver cirrhosis.4 There is no effective medical therapy that can halt disease progression in PSC. The only curative option to date is liver transplantation.

The aetiology of PSC is still largely unknown. The aetiology is most likely to be multifactorial, in which the occurrence of PSC could be triggered by environmental factors in a genetic susceptible host.5 The relationship between susceptibility to PSC and environmental factors has been studied for several risk factors, of which smoking has repeatedly been shown to be associated with a decreased risk of developing PSC, independent of its protective effect in UC.6

Already in 1983, the identification of associations between PSC and HLA-B8 of the human leucocyte antigen (HLA) complex located on chromosome 6—harbouring several genes that are involved in antigen presentation and are important in immunity—raised interest in the role of genetics in PSC.7 This was amplified by a large Swedish study on PSC heritability demonstrated a nearly 4 to 17 times increased risk for first-degree relatives of patients with PSC to develop PSC when compared with the general population.8 The additional 3.3 times increased risk of UC and the presence of at least one concomitant immune-mediated disease outside the liver and bowel in approximately 20% to 25% of patients with PSC suggests a shared genetic component between these diseases.8–10 Over the last 5 years, the application of genome-wide association studies has resulted in an increasing insight in the genetic architecture of PSC, with the identification of 19 non-HLA risk loci at the time of writing.11–14

Little is known about the genetic contribution to the severity and progression of complex diseases in general and PSC specifically. In Mendelian traits like cystic fibrosis and haemochromatosis, consortia efforts have led to the identification of robust and important modifier genes.15,16 If genetic variants would be associated with PSC phenotypes, this could enable risk stratification of patients with PSC according to disease behaviour and would lead to insight into pathogenetic mechanisms associated to disease progression. While translational research from susceptibility genes has yet to prove useful for the development of new drugs in complex disease, modifier genes may point towards pathways involved in disease progression amenable by pharmacological interventions.

The aim of this study is to identify genetic variants associated with PSC disease progression and development of complications, in a large, international, multicentre PSC cohort.

Methods

Study design and patients

Patients with PSC previously recruited throughout Europe, the USA and Canada and genotyped using the Immunochip by Liu et al13 were included. Subject recruitment was approved by the ethics committees or institutional review boards of all participating centres. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Patients of whom PSC diagnosis was revised after they were genotyped were excluded.

The following phenotypic data were collected for patient and disease characteristics: sex, date of birth, PSC subtype (small or large duct), date of PSC diagnosis, intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic disease, dominant strictures, concomitant IBD and type of IBD, date of IBD diagnosis and smoking status. Furthermore, follow-up data were collected for date and cause of death, date and indication of liver transplantation, occurrence and date of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), CCA, CRC, gallbladder carcinoma and occurrence and date of a colectomy.

PSC diagnosis was based on clinical, biochemical, cholangiographic and histological criteria, as formulated by the European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines.17 IBD diagnosis was scored based on accepted endoscopic, radiological and histological criteria.18

PSC-related death was defined as death from liver failure, death from cholangiosepsis, death from CCA or death from gallbladder carcinoma. The time-to-event phenotype liver transplant-free survival was defined as the time between PSC diagnosis and the composite endpoint of either liver transplantation or PSC-related death.

We used genotype data of patients with PSC as previously described.13 Online supplementary appendix 1 describes the quality control applied to this dataset. A total of 130 422 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for 3402 PSC samples remained after quality control and were used in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The age at PSC diagnosis was expressed as median value and IQR. Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages based on non-missing values.

Binary associations

Binary associations were calculated using multiple logistic regression. We corrected for clinical covariates by adding them to the regression model. To determine which clinical covariates to correct for, we performed a backward elimination procedure per binary phenotype. We started with the full model including sex, country, date of PSC diagnosis, established IBD diagnosis and smoking status and removed covariates from the model until the Akaike information criterion stabilised.

Time-to-event associations

Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the effect of genetic variants on time-to-event PSC subphenotypes. Clinical variables that were significantly associated with the time-to-event phenotype in univariable Cox regression analyses (p<0.05) were entered into a multivariable Cox model alongside the genotype. To visualise the effect of genotype on time-to-event phenotypes, Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were plotted (see methods described in online supplementary appendix 1).

We used the SNP2HLA software19 to impute classical HLA alleles from genotype data for HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQA1, HLA-DQB1, HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 and their corresponding amino acid polymorphisms from the genotype data (methods described in online supplementary appendix 1).

Mouse experiments and in vitro experiments on the role of RSPO3 in PSC

Mouse experiments

C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Charles River (Milan, Italy). Normal C57BL/6 mice were sacrificed at the age of 8–10 weeks. Organs were harvested and washed by cold phosphate buffered saline. Cholangiocytes were isolated both from normal mice (n=3) and from mice (n=3) fed 0.1% 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine (DDC) for 4 weeks, as a model of sclerosing cholangitis.20 Total RNA was extracted and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine (see online supplementary appendix 1 for more details).

In vitro experiments on human primary biliary tissue, cholangiocyte-like cells and hepatic stellate cells

Human primary biliary tissue was obtained from a liver and pancreas organ donor after obtaining informed consent from the donor's family. A section of the bile duct was excised and homogenised and RNA was extracted. Cholangiocyte-like cells (CLCs) were generated from human induced pluripotent stem cells and cultured. RSPO3 expression was determined using quantitative PCR (qPCR) and compared with the housekeeping gene using the 2−ΔCt method.21 Next to that, we used previously published microarray data to verify RSPO3 expression.22 The R/Bioconductor package limma23 was used to evaluate differential expression between pairs of conditions (human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hIPSCs) and CLCs and hIPSCs and primary bile duct). A linear model fit was applied and p values were corrected using the method of Benjamini and Hochberg.24 Methods are further described in online supplementary appendix 1.

Primary human hepatic stellate cells were isolated and cultured from wedge sections of liver tissue, obtained from patients undergoing surgery at the Royal Free Hospital in London. Total RNA was extracted and retrotranscribed into complementary DNA, which was used for gene expression assessment with qPCR. Gene expression was compared with the housekeeping gene using the 2−ΔCt method.

Results

Patient characteristics and natural history

Clinical characteristics of the PSC cohort are described in table 1. The cohort consisted of 2881 patients from Europe and 521 patients from the USA and Canada (see online supplementary table 1). A total of 2185 (65%) patients were male, and the median age at PSC diagnosis was 38.6 years (IQR 28.0–50.1). Concomitant IBD was diagnosed in 2390 (75%) patients. The median follow-up was 8.7 years. In total, 874 (26%) patients underwent liver transplantation and 181 (5%) patients died of PSC-related causes. Over 11% of patients developed a malignancy, most often CCA (5.6%) or CRC (4.3%).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the PSC cohort consisting of 3402 patients

| Variable | Groups | Number (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age at PSC diagnosis* | 38.6 years old (28.0–50.1) | |

| Sex | Male | 2185 (64.7) |

| Female | 1193 (35.3) | |

| Missing | 24 (0.7) | |

| Main diagnosis | PSC | 3159 (94.6) |

| Small duct PSC | 75 (2.2) | |

| PSC with AIH overlap | 107 (3.2) | |

| Missing | 61 (1.8) | |

| Liver transplantation | Yes | 874 (26.3) |

| No | 2444 (73.7) | |

| Missing | 84 (2.5) | |

| Colectomy | Yes | 419 (12.6) |

| No | 2897 (87.4) | |

| missing | 86 (2.5) | |

| IBD | No IBD | 816 (25.5) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 1940 (60.5) | |

| Crohn's disease | 357 (11.1) | |

| IBD-U | 93 (2.9) | |

| Missing | 196 (5.8) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | Yes | 188 (5.6) |

| No | 3147 (94.4) | |

| Missing | 67 (2.0) | |

| Colorectal carcinoma | Yes | 127 (4.3) |

| No | 2822 (95.7) | |

| Missing | 453 (13.3) | |

| Gall bladder carcinoma | Yes | 30 (1.0) |

| No | 2977 (99.0) | |

| Missing | 395 (11.6) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Yes | 22 (0.7) |

| No | 2984 (99.3) | |

| Missing | 396 (11.6) | |

| Smoking status | Smoker | 140 (6.0) |

| Ex-smoker | 529 (22.7) | |

| Non-smoker | 1657 (71.2) | |

| Missing | 1076 (31.6) | |

| Death | Non-PSC related | 47 (1.5) |

| Liver failure | 66 (2.1) | |

| Cholangiosepsis | 18 (0.6) | |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 12 (0.4) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 85 (2.6) | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 6 (0.2) | |

| Colorectal carcinoma in case of coexisting IBD | 3 (0.1) | |

| Alive | 2977 (92.6) | |

| Missing | 188 (5.5) |

Quantitative data are expressed as counts and percentages excluding missing data.

Values shown as median (IQR).

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; IBD-U, inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Genetic associations with binary subphenotypes

Genome-wide association analyses focusing on the occurrence of malignancy in patients with PSC revealed several suggestive associations (see online supplementary table 2). When comparing 107 patients with PSC autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) with 3159 patients with PSC but without AIH overlap, a strong genetic association in the HLA-DQB1 gene was identified (top SNP rs3891175, p=4.6×10−11, OR=2.41). After imputation of the classical HLA alleles, we found that the alleles DQA1*05:01 and DQB1*02:01 were most significantly associated with PSC/AIH overlap (p values of 3.8×10−11 and 1.8×10−07). For other binary subphenotypes—small duct PSC, the occurrence of HCC, gallbladder carcinoma and proctocolectomy—no genetic associations were found.

Genetic associations with time-to-event subphenotypes

Next, we aimed to determine whether genetic variants are associated with important time-to-event variables reflecting the PSC disease course, for example, time between PSC diagnosis and the development of a carcinoma. For this, we developed a framework to perform immunochip-wide Cox proportional hazards analyses. We defined the liver transplant-free survival subphenotype as time from PSC diagnosis until liver transplantation or PSC-related death.

Univariable Cox regression analyses including clinical parameters showed statistically significant associations with the time to event endpoint transplant-free survival for sex, country, date of PSC diagnosis, established IBD diagnosis and smoking status. Next, we tested 130 422 SNPs for association with liver transplant-free survival using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression, including the genotype effect alongside the significant clinical covariables. We found SNP rs853974 to be associated with liver transplant-free survival of patients with PSC at genome-wide significance (p=6.07×10−9). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a 50.9% (95% CI 41.5% to 59.5%) transplant-free survival for homozygous AA allele carriers of rs853974 compared with 72.8% (95% CI 69.6% to 75.7%) for GG carriers at 10 years after PSC diagnosis (figure 1A). AA homozygotes had a 2.14 (95% CI 1.66 to 2.76) increased hazard, indicating a 2.14 larger relative risk for need for liver transplantation or for PSC-related death compared with GG homozygotes. Figure 1B shows a regional plot of this observed association.

Figure 1.

Association of genetic variants on chromosome 6 with transplant-free survival of patients with PSC. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves of transplant-free survival. Patients are stratified according to their genotype for SNP rs853974. The p value for genotype effect in the Cox proportional hazards model is p=6.07.10−09. (B) Regional association plot for transplant-free survival. The Y-axis shows the −log10(p value) for genotype effect in the Cox proportional hazards model. PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

SNP rs853974 is located on chromosome 6. We did not identify a direct functional effect of this SNP on gene expression or regulatory features (see online supplementary appendix 1). We hypothesised that neighbouring gene R-Spondin 3 (RSPO3) would be the most likely positional candidate gene. The other neighbouring gene, CENPW, has a fundamental role in kinetochore assembly and is required for normal chromosome organisation and progress through mitosis and thtaberefore not a good candidate. In addition to SNP rs853974, additional suggestive genetic associations with time-to-event phenotypes liver transplant-free survival and time to CCA were found (see online supplementary table 3).

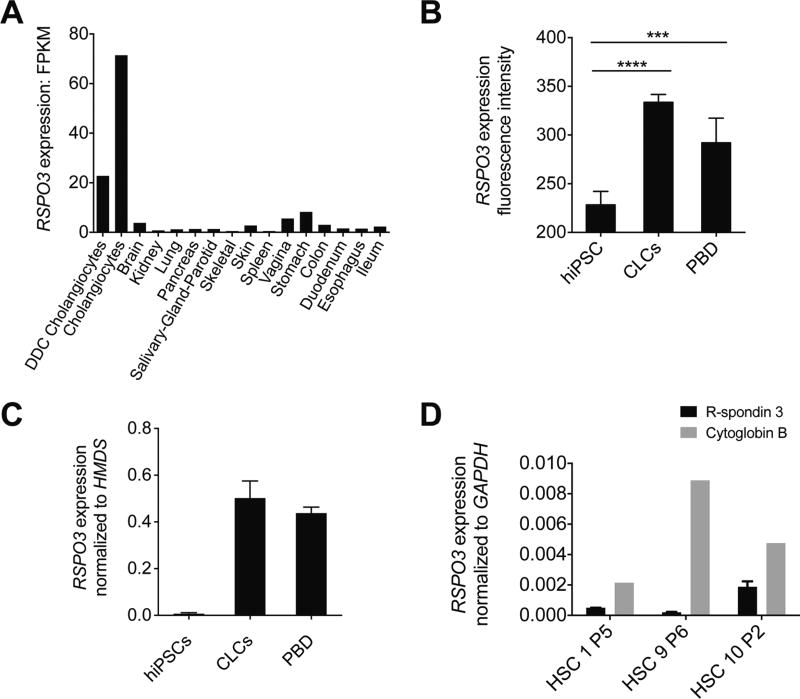

Expression of RSPO3 in key liver-resident effector cells

To assess whether RSPO3 is expressed in disease-relevant cells (cholangiocytes and hepatic stellate cells), we performed RNA sequencing on healthy and cholestatic cholangiocytes and multiple organs derived from normal C57BL/6 mice. RSPO3 expression was 7 to 20 folds higher in cholangiocytes as compared with any of the organs. Furthermore, RSPO3 expression was higher in healthy cholangiocytes than in cholestatic cholangiocytes (figure 2A).

Figure 2.

RSPO3 expression in mouse cholangiocytes and in human CLCs, PBD and HSCs. (A) RNA sequencing analysis of RSPO3 expression in DDC-induced cholestatic cholangiocytes, healthy cholangiocytes and multiple organs of normal C57BL/6 mice. (B) Microarray RSPO3 expression in hiPSCs, CLCs and PBD. RSPO3 expression is significantly increased in CLCs and in PBD compared with hiPSCs. n=3; error bars, SD. Asterisks represent statistical significance (****adjusted p<0.0001, ***adjusted p<0.001, Benjamini and Hochberg corrected p values). (C) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis demonstrating the expression of RSPO3 in hiPSC-derived CLCs and PBD samples compared with expression in hiPSCs. Expression levels are fold changes compared with housekeeping gene HMDS calculated using the 2−ΔCt method. (D) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis showing expression of RSPO3 and cytoglobin B in three patients without PSC. Cytoglobin B messenger RNA expression was evaluated as specific HSC marker. Target genes were normalised using GAPDH as endogenous control and their relative expression was calculated with the 2−ΔCt method. CLCs, cholangiocyte-like-cells; DDC, 3,5-diethoxycarbonyl-1,4-dihydrocollidine; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of exon per million mapped reads; hIPSC, human-induced pluripotent stem cells; HSC, hepatic stellate cell; PBD, primary bile duct.

Next, using microarrays, we assessed expression of RSPO3 in hIPSCs, hIPSC-derived CLCs, and human PBD samples. RSPO3 expression was significantly higher in CLCs and PBD cells compared with hIPSCs (figure 2B). This finding was confirmed by qPCR (figure 2C).

Since activated hepatic stellate cells are the main cells involved in liver fibrosis,25 we also investigated expression of RSPO3 in human culture-activated hepatic stellate cells. We isolated, cultured and activated human hepatic stellate cells of three patients without PSC. Using qPCR, we observed expression of the hepatic stellate cell marker gene cytoglobin B, as well as expression of RSPO3 in all three subjects (figure 2D). We did not observe RSPO3 expression in human CD4 and CD8 T lymphocytes (data not shown).

Discussion

To date, very few disease-modifying genes have been identified in rare complex diseases. Collaboration within the international PSC study group enabled the establishment of a cohort of unprecedented size, for an orphan disease such as PSC, enabling the investigation of genetic variation underlying the progression of PSC through time. Overall, it is a major challenge to determine genetic variants associated with survival, and only few genetic studies investigating this have been published.26 We present a conceptually new method to determine associations between genetic variants and disease course, using genome-wide multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression analyses. Here, we identify a genome-wide significant association between SNP rs853974 —located close to the RSPO3 gene—and liver transplant-free survival in PSC. Interestingly, this locus is not associated with PSC susceptibility and thus exemplifies different genetic regulation of disease susceptibility and disease progression.

This study is based on genotype data obtained using Illumina immunochip, a genotyping platform that densely covers genetic regions associated to immune-mediated diseases. Use of genome-wide association study (GWAS) arrays, that more uniformly cover genetic variants all over the genome, would have been ideal. However, a complete GWAS dataset for the entire international cohort was not available at the time of study. For that reason, we started with the available immunochip data. Given the positive findings in this study, a similar study on GWAS arrays data could very well be of additional value.

For the binary phenotype of developing CCA or not, we found an association at chromosome 5 at 150 Mb (see online supplementary table 2). Of interest, this locus contains an established genetic association with Crohn’s disease susceptibility in the autophagy gene IRGM.27 For the phenotype of developing colorectal carcinoma or not, we found an association at chromosome 14 at 35 Mb. This locus appeared not to be associated with sporadic colorectal cancer.

Since transplant-free survival is a combined and heterogeneous phenotype, we assessed to which extent the following three subgroups contribute to the association:

(1) transplanted patients with indication for transplantation ‘end stage liver disease’ and patients died because of ‘liver failure’; (2) transplanted patients with indication for transplantation ‘cholangiocarcinoma (cca)/high-grade dysplasia’ and patients died because of ‘cca or gallbladder carcinoma’ and (3) transplanted patients with indication for transplantation ‘intolerable complaints/pruritus/recurrent cholangitis’ and patients died of ‘cholangiosepsis’. We observed a stronger contribution of subgroups 1 and 3 to the association, indicating that the underlying biological mechanism is more likely one involved in causing progression of liver disease and/or cholangitis or cholangiosepsis rather than a mechanism involved in cancer development.

RSPO3 is a member of the R-Spondin protein family (R-Spondin 1–4).28 These proteins are secreted agonists of the canonical Wnt/beta (β)-catenin signalling pathway.28 They activate the pathway leading to induced transcription of Wnt target genes. Wnt/β-catenin signalling plays a central role in embryogenesis, organogenesis and adult homeostasis and is a critical regulator of stem cell maintenance.29,30 RSPO3 is a ligand of the Frizzled 8 and LRP5/6 receptors.28 In the canonical form of the Wnt pathway, binding of ligands to the Frizzled receptor and LRP5 or 6 coreceptors causes β-catenin to dephosphorylate in the cytoplasm. Accumulated β-catenin translocates to the nucleus where it binds to T cell factor/Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor, causing transcription of Wnt target genes—such as Fibronectin, MMP-7, Twist and Snail. These factors activate hepatic stellate cells and induce liver fibrosis. Blocking the Wnt signalling pathway using Dickkopf-1, a Wnt coreceptor antagonist, restores hepatic stellate cells quiescence in culture.31 Hence, Wnt signalling is involved in both progression and regression of liver fibrosis, either by inhibiting or promoting activation and survival of hepatic stellate cells.31,32 Also, RSPOs have been shown to facilitate hepatic stellate cell activation and promote hepatic fibrogenesis.33 Here, we demonstrate that RSPO3 is expressed in key effector cells involved in the pathogenesis of PSC. Since we have shown that patients with PSC that are homozygote AA carriers of rs853974 progress more rapidly towards PSC-related death or liver transplantation, RSPO3 can be regarded a plausible candidate gene to be involved in PSC disease progression. Hypothetically, patients with PSC might benefit from reduction of RSPO3 or generally canonical Wnt signalling.

In an immunochip analysis of the International IBD Genetics Consortium including over 75 000 individuals,34 an intronic SNP rs9491697 in RSPO3 (which is not in linkage disequilibrium with rs853974, r2=0.014) was identified to be associated with Crohn’s disease (p=3.79×10−10, OR=1.077) but not with UC. Given the small number of patients with Crohn’s disease (n=357) within the present study, the lack of linkage disequilibrium between the two ‘hit SNPs’ and the fact that our multivariate Cox model corrected for IBD-status, the identified association signal does not seem to be driven by the co-occurrence of Crohn’s disease in our cohort.

For several binary and time-to-event subphenotypes, we found suggestive genetic associations. Two additional SNPs, rs1532244 on chromosome 3 and rs17649817 on chromosome 5, were suggestively associated with transplant-free survival. Furthermore, one SNP, rs7731017, was suggestively associated with the presence of CCA. We investigated whether any of the candidate genes in the locus overlapped with genes identified in tumour sequencing studies of CCA. We did not find an overlap with the 32 genes reported to be significantly altered in intrahepatic, extrahepatic and gallbladder cancer by Nakamura et al.35 When comparing the genes in our CCA locus with 1146 genes containing non-synonymous somatic mutations in intrahepatic CCA,36 we found that the SYNPO gene was both in the list of 1146 genes of the sequencing study as well as in the locus that we identified to be associated with the presence of CCA. There is little known about this gene and there is no connection with oncogenesis. Another gene, SP100, was found in this study to be in the locus associated with time to CCA and is also in the list of 1146 genes. SP100 is associated with autoimmune disease of the urogenital tract and also with PBC. Interestingly, anti-sp100 autoantibodies have been described for PBC.37 The genetic association of SP100 with both PBC and the time to CCA within patients with PSC as well as the existence of anti-sp100 autoantibodies makes this an interesting gene for future follow-up studies.

When comparing patients with PSC-AIH with patients with PSC but without AIH, we found a strong genetic association with PSC-AIH in the HLA-DQB1 gene. The identified variant was tagging the classical HLA haplotypes DQA1*05:01 and DQB1*02:01. These associations overlap the associations found by a previous genome-wide association study of AIH type 1 in the Netherlands,38 suggesting that the genetic basis for AIH type 1 pathogenesis is similar for patients with isolated AIH type 1 compared with patients with PSC-AIH.

This study is limited by the relatively small cohort size when compared with other GWAS studies that incorporate tens of thousands of samples. The resulting lack of statistical power may have played a role in the binary analyses, in which suggestive hits were found for CCA and CRC but genome-wide significance was not reached. However, PSC is a rare disease, and the present study has included patients recruited throughout the world in a joined effort. It is therefore not expected that a larger cohort of PSC cases will become available soon.

In conclusion, we present the largest association study of PSC genotypes with disease phenotypes to date. We identified several genetic variants associated with PSC disease course. Specifically, we report rs853974 to be genome-wide significantly associated with liver transplant-free survival in PSC. Findings of candidate gene RSPO3 being expressed in both mouse and human cholangiocytes and human-activated hepatic stellate cells warrant further assessments of the role of this potential key PSC modifier gene.

Supplementary Material

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

-

►

Several case–control genome-wide association studies have revealed 20 susceptibility loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis.

-

►

Little is known about the genetic contribution to the severity and progression of complex diseases in general and primary sclerosing cholangitis in particular.

-

►

RSPO3 plays a role in the activation of the canonical Wnt signalling pathway, which is involved in liver fibrosis.

What are the new findings?

-

►

The genetic variant rs853974 is genome-wide significantly associated with liver transplant-free survival in primary sclerosing cholangitis.

-

►

Candidate gene RSPO3 is expressed in both murine and human cholangiocytes and in human hepatic stellate cells.

-

►

Three new loci were found to be associated with time to cholangiocarcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

-

►

Through its effect on liver fibrosis, RSPO3 could play an important role in PSC disease progression, and insight in its mechanism could lead to new therapeutic targets.

-

►

Furthermore, since we demonstrated that genetic variants are associated with PSC disease progression, genetics could provide a tool for risk stratification of patients with PSC in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients with PSC for participating in this study. We acknowledge the members of the International PSC Study Group and the UKPSC Consortium for their participation. We acknowledge Lukas Tittman for providing samples.

Funding RA is supported by a PSC Partners Seeking a Cure grant ‘Unraveling genetics driving PSC subphenotypes: anIPSCSG study’. LV and FS are supported by the ERC grant Relieve IMDs and the Cambridge Hospitals National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Center. SH is supported by a grant from the German Research Community (DFG), grant HO 4460/2–1. TM is supported by the German Research Community (DFG), grants MU 2864/1–1 and MU 2864/1–3. KNL is supported by the NIH RO1 DK 084960 and Sigismunda Palumbo Charitable Trust. EAMF is supported by a Career Development Grant from Dutch Digestive Foundation (Maag Lever Darm Stichting, MLDS). RKW is supported by a VIDI grant (016.136.308) from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and a PSC Partners Seeking a Cure grant ‘The Exome in PSC’.

Footnotes

Contributors RA, EMGdV, XJ, FS, KR, KS, ALM and WW: statistical analysis and interpretation of data. CYP and RKW: study supervision. KR, KS, XJ, FS and MP: performed experiments. RA, EMGdV, THK, SH, CS, TF, JRH, EM, FS, CYP and RKW wrote the manuscript. JZL, AFranke, DE and CAA performed genotyping, calling and QC. RA, EMGdV, ECG, XJ, FS, KR, KS, TF, TJW, ALM, WW, GA, DA, AB, NKB, UB, EB, KMB, CLB, MCB, MC, OC, AC, GD, JE, BE, DE, MF, EAMF, AFloreani, IF, DNG, GMH, BvH, KH, SH, JRH, FI, PI, BDJ, HL, WL, JZL, H-UM, MM, EM, PM, TM, AP, CRupp, CRust, RNS, CS, SS, ES, MSilverberg, BS, MSterneck, AT, LV, JV, AVV, BdV, KZ, RWC, MPM, MP, SMR, KNL, AFranke, CAA, THK, CYP, RKW, The UK–PSC Consortium and The International PSC Study Group contributed to sample and clinical data collection. All authors revised the manuscript for critical content and approved the final version.

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval Subject recruitment was approved by the ethics committees or institutional review boards of all participating centres.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hirschfield GM, Karlsen TH, Lindor KD, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Lancet. 2013;382:1587–99. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boonstra K, Beuers U, Ponsioen CY. Epidemiology of primary sclerosing cholangitis and primary biliary cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1181–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boonstra K, Weersma RK, van Erpecum KJ, et al. Population-based epidemiology, malignancy risk, and outcome of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2013;58:2045–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.26565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boberg KM, Lind GE. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and malignancy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:753–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eaton JE, Talwalkar JA, Lazaridis KN, et al. Pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis and advances in diagnosis and management. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:521–36. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell SA, Thyssen M, Orchard TR, et al. Cigarette smoking, appendectomy, and tonsillectomy as risk factors for the development of primary sclerosing cholangitis: a case control study. Gut. 2002;51:567–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapman RW, Varghese Z, Gaul R, et al. Association of primary sclerosing cholangitis with HLA-B8. Gut. 1983;24:38–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.1.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergquist A, Montgomery SM, Bahmanyar S, et al. Increased risk of primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis in first-degree relatives of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:939–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamberts LE, Janse M, Haagsma EB, et al. Immune-mediated diseases in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:802–6. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saarinen S, Olerup O, Broomé U. Increased frequency of autoimmune diseases in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3195–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Folseraas T, Melum E, Rausch P, et al. Extended analysis of a genome-wide association study in primary sclerosing cholangitis detects multiple novel risk loci. J Hepatol. 2012;57:366–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellinghaus D, Folseraas T, Holm K, et al. Genome-wide association analysis in primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis identifies risk loci at GPR35 and TCF4. Hepatology. 2013;58:1074–83. doi: 10.1002/hep.25977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu JZ, Hov JR, Folseraas T, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related disease regions identifies nine new risk loci for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Nat Genet. 2013;45:670–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellinghaus D, Jostins L, Spain SL, et al. Analysis of five chronic inflammatory diseases identifies 27 new associations and highlights disease-specific patterns at shared loci. Nat Genet. 2016;48:510–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett JR, Friedman KJ, Ling SC, et al. Genetic modifiers of liver disease in cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 2009;302:1076–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stickel F, Buch S, Zoller H, et al. Evaluation of genome-wide loci of iron metabolism in hereditary hemochromatosis identifies PCSK7 as a host risk factor of liver cirrhosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3883–90. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lennard-Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1989;170:6–19. doi: 10.3109/00365528909091339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.European Association for the Study of the Liver’. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia X, Han B, Onengut-Gumuscu S, et al. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS One. 2013;8:e64683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fickert P, Stöger U, Fuchsbichler A, et al. A new xenobiotic-induced mouse model of sclerosing cholangitis and biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:525–36. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sampaziotis F, Cardoso de Brito M, Madrigal P, et al. Cholangiocytes derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells for disease modeling and drug validation. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:845–52. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth GK. Linear models and empirical bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3:1–25. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mederacke I, Hsu CC, Troeger JS, et al. Fate tracing reveals hepatic stellate cells as dominant contributors to liver fibrosis independent of its aetiology. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2823. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu C, Li D, Jia W, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies common variants in SLC39A6 associated with length of survival in esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:632–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007;39:830–2. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nam JS, Turcotte TJ, Smith PF, et al. Mouse cristin/R-spondin family proteins are novel ligands for the frizzled 8 and LRP6 receptors and activate beta-catenin-dependent gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13247–57. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508324200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Amerongen R, Nusse R. Towards an integrated view of Wnt signaling in development. Development. 2009;136:3205–14. doi: 10.1242/dev.033910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Lau WB, Snel B, Clevers HC. The R-spondin protein family. Genome Biol. 2012;13:242. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-3-242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng JH, She H, Han YP, et al. Wnt antagonism inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G39–G49. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00263.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myung SJ, Yoon JH, Gwak GY, et al. Wnt signaling enhances the activation and survival of human hepatic stellate cells. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2954–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xinguang Y, Huixing Y, Linlin W, et al. RSPOs facilitated HSC activation and promoted hepatic fibrogenesis. Oncotarget. 2016;5 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491:119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakamura H, Arai Y, Totoki Y, et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat Genet. 2015;47:1003–10. doi: 10.1038/ng.3375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao Q, Zhao YJ, Wang XY, et al. Activating mutations in PTPN3 promote cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and migration and are associated with tumor recurrence in patients. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1397–407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman GL, Bialek A, Encabo S, et al. Is prevalence of PBC underestimated in patients with systemic sclerosis? Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:762–4. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Boer YS, van Gerven NM, Zwiers A, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants associated with autoimmune hepatitis type 1. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:443–52. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.