Abstract

We assessed which combinations of risk factors can classify adults who develop accelerated knee osteoarthritis (KOA) or not and which factors are most important. We conducted a case-control study using data from baseline and the first 4 annual visits of the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Participants had no radiographic KOA at baseline (Kellgren-Lawrence [KL]<2). We classified 3 groups (matched on sex): 1) accelerated KOA: ≥1 knee developed advance-stage KOA (KL=3 or 4) within 48 months, 2) typical KOA: ≥1 knee increased in radiographic scoring (excluding those with accelerated KOA), and 3) No KOA: no change in KL grade by 48 months. We selected 8 predictors: serum concentrations for C-reactive protein, glycated serum protein (GSP), and glucose; age; sex; body mass index; coronal tibial slope, and femorotibial alignment. We performed a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis to determine rules for classifying individuals as accelerated KOA or not (no KOA and typical KOA). The most important baseline variables for classifying individuals with incident accelerated KOA (in order of importance) were age, glucose concentrations, BMI, and static alignment. Individuals <63.5 years were likely not to develop accelerated KOA, except when overweight. Individuals >63.5 years were more likely to develop accelerated KOA except when their glucose levels were ≥81.98 mg/dL and they did not have varus malalignment. The unexplained variance of the CART=69%. These analyses highlight the complex interactions among four risk factors that may classify individuals who will develop accelerated KOA but more research is needed to uncover novel risk factors.

Keywords: knee, osteoarthritis, classification, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

For most people who develop knee osteoarthritis (KOA), the disease develops gradually over several years. However, 3.4% of adults at risk for KOA will develop an accelerated form of KOA, which we defined as the onset of advanced-stage disease within 4 years and that typically develops in less than 12 months (1–3). Accelerated KOA is a painful disorder (3) and associated with several risk factors: greater age, greater body mass index (BMI), recent knee injury, static knee alignment, and coronal tibial slope (1; 4; 5). While no single risk factor can accurately predict who is at risk for accelerated KOA, it would be beneficial to recognize the combinations and interactions of risk factors that identify people at risk for accelerated KOA.

While accelerated KOA represents 22% of incident cases of KOA in the Osteoarthritis Initiative cohort, the small sample size makes it is challenging to study complex interactions among risk factors. Furthermore, the nonlinear association between some risk factors and incident KOA (6) makes this even more challenging with common statistical methods (e.g., multinomial logistic regression). Classification and regression tree (CART) analysis overcomes these issues by using a non-parametric and nonlinear method to identify the most discriminating risk factor and associated cut point to differentiate two groups (e.g., accelerated KOA or no accelerated KOA) and then continue to find the next best risk factor and cut point (7; 8). Unlike traditional methods, a CART analysis can inform clinicians and researchers about the most important risk factors for classifying individuals and clarify potential complex interactions among risk factors.

Hence, we used a CART analysis to assess which combinations of risk factors can be used classify adults who develop accelerated KOA or not, and which risk factors are most important. We selected risk factors based on significant findings from our prior evaluations of risk factors for accelerated KOA (1–5). We hypothesized that age and BMI would be the most important risk factors. The results of this study will be valuable for developing predictive models to identify individuals at risk for accelerated KOA yet more immediately may help inform clinicians about high-risk groups of adults.

METHODS

We conducted a case-control study using data and images from baseline and the first four years of follow-up in the OAI. The OAI is a longitudinal multicenter observational study of adults with or at risk for KOA at four clinical sites in the United States: Memorial Hospital of Rhode Island, The Ohio State University, University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University, and the University of Pittsburgh. The staff enrolled 4,796 men and women (45 to 79 years of age) between February 2004 and May 2006. Descriptions of the eligibility criteria and the OAI protocol are publicly accessible at the OAI website (9). Institutional review boards at each OAI clinical site and the coordinating center (University of California, San Francisco) approved the OAI study and all participants provided informed consent.

Case and Control Definitions

We assessed 3 groups that we defined based on radiographic definitions of KOA. Everyone had no radiographic KOA (Kellgren-Lawrence [KL] grade < 2) in either knee at baseline. The cases were adults with accelerated KOA, which we defined as someone who developed advanced-stage KOA (KL grade 3 or 4, development of a definite osteophyte and joint space narrowing) within 48 months (n = 54). The first group of controls was individuals with a gradual onset of KOA (typical KOA) who had at least 1 knee that increased in radiographic scoring within 48 months (excluding those with accelerated KOA; n = 187). The second control group was individuals with no KOA who had no change in KL grade in either knee from baseline to the 48-month follow-up (n = 1,325). Participants were required to have baseline knee radiographs and enough follow-up radiographs to guarantee no misclassification. Specifically, we omitted individuals without accelerated KOA who had no 48-month radiograph to reduce the risk of misclassifying a possible case as a control.

To ensure timely completion of assessments, we did 1:1:1 matching for the three groups based on sex. Matching was completed at random. Each group had 54 participants. The index knee among those with accelerated or typical KOA was the knee that first met the definition of accelerated or typical KOA, respectively. We defined the index knee of an individual with no KOA to be the same knee as that person’s matched member of the accelerated KOA group.

For this study, we combined those with typical KOA and no KOA. This enabled us to explore if combinations of risk factors could classify adults who develop accelerated KOA from a sample with adults with and without radiographic progression.

Knee Radiographs and Semi-Quantitative Grading

Participants had bilateral weight-bearing, fixed-flexion posteroanterior knee radiographs at baseline and the first 4 annual follow-up visits. Central readers, who were blinded to the order of follow-up radiographs, scored the images for KL grades. The read-reread agreement for these readings was good (weighted κ [intrarater reliability] = 0.70–0.80). These KL grades are publicly accessible (files: kXR_SQ_BU##_SAS [versions 0.6, 1.6, 3.5, 5.5, and 6.3]) (9).

Acquisition of Biospecimens

Staff performed blood draws at the baseline visit at least one hour after the participant had awoken. Participants were asked to fast for at least 8 hours prior to the study visit. Immediately after the blood draw, staff inverted the serum sample tubes and then kept the tubes at room temperature for 30 minutes (maximum = 60 minutes). Next, the study staff centrifuged the tubes at 4°C (30,000 g-minutes) and immediately transferred the biospecimens to cryovials. Within 15 minutes of being aliquoted into cryovials, the samples were placed in a −70°C freezer for at least 30 minutes prior to shipping to Fisher Bioservices (Rockville, MD) for long-term storage. In September 2015, Fisher Bioservices shipped the serum samples to Temple University School of Medicine. The full protocols for the biospecimens collection and processing are accessible on the OAI website (9).

Biochemical Assays

One investigator (MA) performed all assays in duplicate at Temple University School of Medicine within 2 months of delivery. The biospecimens were de-identified to ensure the investigator was blinded. To assess serum high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, we used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (ELISA, Novex by Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA; range = 18.75 to 1200 pg/mL, sensitivity = 18.75 pg/mL, coefficient of variation <7.52% for intra-assay precision, and coefficient of variation <10% for inter-assay precision). To assess glycated serum protein (GSP) levels, we used an ELISA kit (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA; range = 78.125 nmol/mL to 1000nmol/mL, sensitivity = 48.875 nmol/mL, and coefficient of variation <10%). Samples used for glucose analyses were deproteinized prior to analysis with 10kD Spin Columns (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). For fasting glucose levels we used Abcam Glucose Assay Kits (Cambridge, MA, USA; range = 1 – 1000 µM, sensitivity = 1 µM, and coefficient of variation <2%).

Clinical Data

At baseline, age, sex, and BMI were acquired based on a standard protocol. The data and protocol are publicly available (9).

Coronal Tibial Slope

We measured the coronal tibial slope on weight-bearing, fixed-flexion posteroanterior knee radiographs. Details of these methods have been previously described (5). In brief, one reader (JBD) completed all of the measurements using an EFilm Workstation 3.4 (Merge Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA). First, the reader defined the longitudinal axis of the tibia. Next, the reader drew a line joining the peak points of the medial and lateral aspects of the tibial plateau. The reader then shifted the longitudinal axis to the peak lateral aspect of the tibial plateau and drew a line perpendicular to the longitudinal axis. If the peak lateral aspect was proximal to the peak medial aspect then the coronal tibial slope angle was positive. The intra-reader reliability was good (ICC3,1 = 0.87, n = 15 knees)(10).

Femorotibial Alignment Angle

Femorotibial angle (FTA) was measured on weight-bearing, fixed-flexion posteroanterior knee radiographs. These methods have been previously described (11) and the methods and data are publicly available on the OAI website (file: kXR_FTA_Duryea00, version 0.2) (9). In brief, a customized software tool defined the tibial axis based on the central point of the knee and the center of the tibial shaft, typically 10cm distal to the tibial plateau. The femoral axis was perpendicular to a line tangent to the distal ends of the medial and lateral femoral condyles. Varus malalignment had more negative values than knees with valgus malalignment. We adjusted FTA to match hip-knee-ankle angles as described in Iranpour-Boroujeni et al (11). The intra- and inter-reader reliability was excellent (intra-reader ICC = 0.98 and inter-reader ICC = 0.98 and 0.99) (11).

Statistical Analysis

We performed CART (12; 13) analysis to determine decision rules for classifying individuals as accelerated KOA or not (no KOA and typical KOA) based on baseline age, BMI, coronal tibial slope, FTA, serum measures and sex. Pruning and 10-fold cross-validation were performed to generate a tree of reasonable size and identify the most important variables. All analyses were performed using the rpart function in R (version 3.2.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

RESULTS

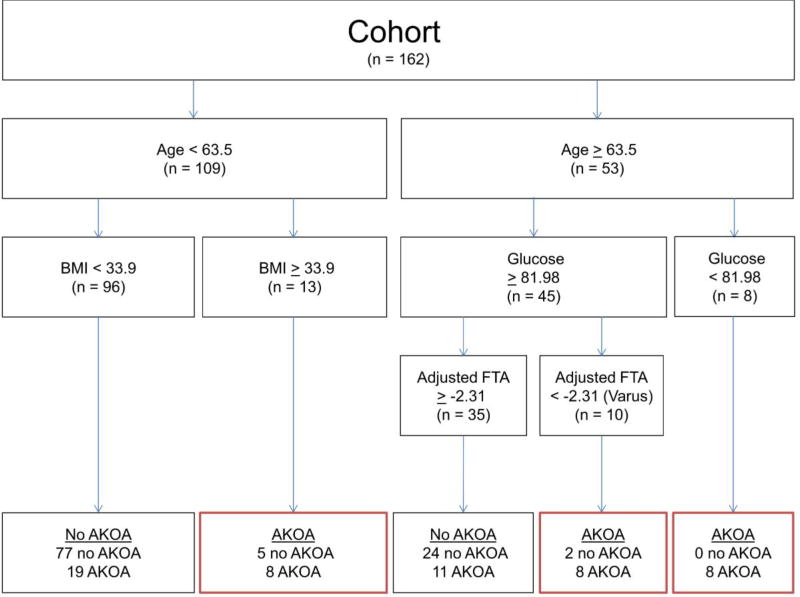

Based on the CART analysis, the most important baseline variables for classifying individuals with incident accelerated KOA (in order of importance) were age, glucose concentrations, BMI, and FTA (Figure 1). Overall, the CART had a sensitivity of 0.44, specificity of 0.94, positive predictive value = 0.77, and negative predictive value = 0.77. The relative error (unexplained variance) of the CART was 69%.

Figure 1. Classification and Regression Tree for Accelerated Knee Osteoarthritis (AKOA) versus those without AKOA.

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index, FTA = femorotibial alignment angle

The first split in the CART analysis divided people by age. Individuals < 63.5 years of age were unlikely to develop accelerated KOA, except when they were obese (BMI ≥ 33.9 kg/m2). For adults over 63.5 years of age glucose concentrations and alignment but not BMI contributed to the classification strategy. Individuals > 63.5 years of age were more likely to develop accelerated KOA except when their glucose levels were ≥ 81.98 mg/dL and they did not have varus malalignment (FTA ≥ −2.31°).

DISCUSSION

Age, BMI, fasting glucose, and static knee alignment may enable the classification of individuals at risk for developing accelerated KOA in the subsequent 4 years. Among these, age may be the most important factor for classifying people who will develop accelerated KOA. Our findings also highlight novel interactions among risk factors, as discussed further below.

We previously found that higher BMI and older age are independently associated with accelerated KOA (1; 4). Additionally, we found an interaction between age and BMI (4). Adults who are both older and have a higher BMI are at greater risk for developing accelerated KOA than those with no KOA (4). Our current analysis supports these prior findings, as well as past findings that younger individuals (45 to 64 years of age) with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 are not at risk for accelerated KOA (4). We also previously found that older individuals were at risk for accelerated KOA if they were overweight and/or had a recent knee injury (4). However, in our current analyses, we found that BMI was not informative among older individuals. Instead older adults were classified as at risk for accelerated KOA if they had low fasting glucose concentrations (< 81.98 mg/dL) or varus malalignment (FTA < −2.31°). Hence, these new findings may indicate that among older adults, metabolic pathways and joint biomechanics may play a greater role in the classification of accelerated KOA than just body mass.

There is conflicting evidence on the role of systemic inflammation and impaired glucose homeostasis on the incidence of radiographic KOA (14–17). Despite prior reports that fasting glucose was not associated with prevalent KOA (18) or incident KOA (17), we found that fasting glucose concentrations may be an important variable for classifying people who will develop accelerated KOA instead of typical KOA or no KOA. While glucose concentrations may play an important role in classifying people this cannot be used to infer that glucose concentrations are part of the causal pathway to accelerated KOA. However, the CART analysis enabled us to look at possible interactions that would be infeasible with other statistical analyses because of the limited sample size. For example, we previously found no relationship between glucose concentrations and incident accelerated KOA but the small sample size prevented us from assessing this relationship among older adults, where the CART analysis suggests it may be an important factor (6). Based on these findings, it may be fruitful to explore the association between fasting glucose levels and incident accelerated KOA among adults over 63.5 years of age.

These results highlight the challenges of classifying people at risk for accelerated KOA. Future studies need to be sufficiently powered to explore interactions among risk factors as well as how some risk factors (e.g., glucose concentrations) may be effect modifiers for the relationship between certain risk factors (e.g., static femorotibial alignment) and incident accelerated KOA.

It is important to note that a considerable portion of the variance (69%) remains unexplained. We previously reported that a recent knee injury – after the OAI baseline – is a risk factor for accelerated KOA. However, we found no association between a history of knee injury before the OAI baseline and accelerated KOA. Hence, recent knee injury, which is an exposure that occurs after baseline, was therefore omitted in this analysis. The omission of this risk factor may account for some of the unexplained variance. We must also consider other novel and unrecognized risk factors that may contribute to the classification of adults who will develop accelerated KOA. For example, we need to identify factors that may be responsible for presence of knee pain that occurs before the onset of accelerated KOA(3; 19). These early knee symptoms may increase the risk of a new injury(20), which could be a catalyst for accelerated KOA.

While this study raises awareness about the complex interactions that may occur among risk factors for accelerated KOA, we acknowledge that this study has limitations. First, we have not replicated this model in an external data set. We believe this is a critical future project but it would be beneficial to address some of the important findings from this study before proceeding with traditional model development and validation. For example, we found that there is a large amount of unexplained variance, we believe this emphasizes the need to explore other novel risk factors that may help classify individuals at risk for accelerated KOA. Additionally, larger samples sizes may enable more in-depth analyses to assess possible interactions. Despite a limited sample size and a large unexplained variance, we believe this study is a critical step towards classifying people who will develop accelerated KOA and will help strengthen future research on accelerated KOA.

In conclusion, age, BMI, fasting glucose concentrations, and static femorotibial alignment may enable the classification of individuals at risk for accelerated KOA in the subsequent 4 years. Among these factors, age may be the most important. We also demonstrated for the first time the complex interplay among risk factors and the need to explore novel risk factors for accelerated KOA. Identifying high-risk groups of adults may lead to targeted prevention strategies. For example, certain prevention strategies (e.g., weight management and injury prevention) may be targeted to younger individuals who are overweight while other strategies may be adopted for older individuals with varus malalignment (e.g., bracing) or impaired glucose homeostasis (e.g., weight management, nutritional counseling). Future predictive models should account for these risk factors, how they interact with one another, and the need to incorporate novel risk factors that may account for the unexplained variance.

Acknowledgments

These analyses were financially supported by a grant from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01-AR065977. The OAI is a public-private partnership comprised of five contracts (N01-AR-2-2258; N01-AR-2-2259; N01-AR-2-2260; N01-AR-2-2261; N01-AR-2-2262) funded by the National Institutes of Health, a branch of the Department of Health and Human Services, and conducted by the OAI Study Investigators. Private funding partners include Merck Research Laboratories; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline; and Pfizer, Inc. Private sector funding for the OAI is managed by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health. This manuscript was prepared using an OAI public use data set and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the OAI investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners. This work was also supported in part by the Houston Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence (HFP90-020). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Statement: All authors drafted the paper or revised it critically as well as read and approved the final submitted version. Driban, Eaton, Amin, and Barbe significantly contributed to the research design as well as acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data. Price, Lu, Lo, and McAlindon also significantly contributed to the research design as well as analysis and interpretation of data. Duryea contributed to both acquisition of data and interpretation of data. Davis also significantly contributed interpretation of data.

The authors have no other conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

References

- 1.Driban JB, Eaton CB, Lo GH, et al. Association of knee injuries with accelerated knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care Res. 2014;66:1673–1679. doi: 10.1002/acr.22359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Stout AC, Lo GH, et al. Best performing definition of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2016;8:165–171. doi: 10.1177/1759720X16658032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Price LL, Eaton CB, et al. Individuals with incident accelerated knee osteoarthritis have greater pain than those with common knee osteoarthritis progression: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin. Rheumatol. 2015;35:1565–1571. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3128-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Eaton CB, Lo GH, et al. Overweight older adults, particularly after an injury, are at high risk for accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1071–1076. doi: 10.1007/s10067-015-3152-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Stout AC, Duryea J, et al. Coronal tibial slope is association with accelerated knee osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:299. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Eaton CB, Amin M, et al. Glucose homeostasis influences the risk of incident knee osteoarthritis: Data from the osteoarthritis initiative. J Orthop Res. 2017 doi: 10.1002/jor.23531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29:1039–1049. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrard S, Speybroeck N, Hermans C. Classification and regression tree analysis vs. multivariable linear and logistic regression methods as statistical tools for studying haemophilia. Haemophilia. 2015;21:715–722. doi: 10.1111/hae.12778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Osteoarthritis Initiative. https://oai.epi-ucsf.org/

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979;86:420–428. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iranpour-Boroujeni T, Li J, Lynch JA, et al. A new method to measure anatomic knee alignment for large studies of OA: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2014;22:1668–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell FE. Regression Modeling Strategies with Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York: Springer-Verlag New York, Inc; 2001. pp. 26–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Friedman J. The Elements of Statisical Learning Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction. New York: Springer-Verlag New York Inc; 2001. pp. 266–279. [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Beguerie JR, Zhang W, et al. Circulating C reactive protein in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:703–710. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi Hosnijeh F, Siebuhr AS, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Association between biomarkers of tissue inflammation and progression of osteoarthritis: evidence from the Rotterdam study cohort. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2016;18:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0976-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, et al. Accumulation of metabolic risk factors such as overweight, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, and impaired glucose tolerance raises the risk of occurrence and progression of knee osteoarthritis: a 3-year follow-up of the ROAD study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20:1217–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engstrom G, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, Rollof J, et al. C-reactive protein, metabolic syndrome and incidence of severe hip and knee osteoarthritis. A population-based cohort study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2009;17:168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garessus ED, de Mutsert R, Visser AW, et al. No association between impaired glucose metabolism and osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2016;24:1541–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Eaton CB, Lo GH, et al. Knee symptoms among adults at risk for accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin. Rheumatol. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10067-017-3564-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driban JB, Lo GH, Eaton CB, et al. Knee Pain and a Prior Injury Are Associated with Increased Risk of a New Knee Injury: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. J. Rheumatol. 2015;42:1463–1469. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]