Abstract

Multiple studies have demonstrated that the pathological geometries unique to each patient can affect the durability of mitral valve (MV) repairs. While computational modeling of the MV is a promising approach to improve the surgical outcomes, the complex MV geometry precludes use of simplified models. Moreover, the lack of complete in-vivo geometric information presents significant challenges in the development of patient-specific computational models. There is thus a need to determine the level of detail necessary for predictive MV models. To address this issue, we have developed a novel pipeline for building attribute-rich computational models of MV with varying fidelity directly from the in-vitro imaging data. The approach combines high-resolution geometric information from loaded and unloaded states to achieve a high level of anatomic detail, followed by mapping and parametric embedding of tissue attributes to build a high resolution, attribute-rich computational models. Subsequent lower resolution models were then developed, and evaluated by comparing the displacements and surface strains to those extracted from the imaging data. We then identified the critical levels of fidelity for building predictive MV models in the dilated and repaired states. We demonstrated that a model with a feature size of ~5 mm and mesh size of ~1 mm was sufficient to predict the overall MV shape, stress, and strain distributions with high accuracy. However, we also noted that more detailed models were found to be needed to simulate microstructural events. We conclude that the developed pipeline enables sufficiently complex models for biomechanical simulations of MV in normal, dilated, repaired states.

1. Introduction

The mitral valve (MV) is a bi-leaflet structure located between the left atrium and ventricle that regulates the unidirectional blood flow during the cardiac cycle. The MV apparatus [1] consists of the anterior and posterior leaflets, annulus, chordae tendineae (MVCT), and papillary muscles (PM). The physiological function of the MV is highly dependent on the interconnected relations between these constituents [2]; with the MV geometry having a particularly critical impact [3, 4]. MV regurgitation (MVR) is the most prevalent valvular heart disease, which will continue to grow as the domestic and international population ages [5]. MVR occurs when the valve leaflets fail to fully cover the MV orifice area and blood leaks to the left atrium during systole, [6]. The causes of MVR can be either primary (myxomatous degeneration and rheumatic fever) or secondary (ischemic left ventricular remodeling) [7]. There are two major treatment strategies for MVR: valve replacement and repair [8]. The major repair strategies include annuloplasty, leaflet resection, and neo-chordoplasty [9].

MV repair has been embraced as the gold standard strategy to treat the regurgitation [10] with excellent initial results for Carpentier’s annuloplasty technique [11]. In the annuloplasty procedure, a ring is sutured on the MV orifice near the MV annulus hinge region to reduce the orifice size so that the leaflet cooptation completely covers the left atrioventricular cavity [12]. Unfortunately, more recent follow-up studies have revealed an undesirable rate of failure and reoperation required for repaired MVs [13]. Importantly, there still exists uncertainty in the optimal shape and size of the annuloplasty rings [14].

While recent studies have shown that patient-specific geometries affect the repair durability and effectiveness [15, 16], the repair planning has remained mostly qualitative. It is believed that the complex structure of the MV plays a significant role in the valvular response to the repair [17]. Yet, isolating the effect of each factor to study the valvular response is not feasible either in vitro or in vivo animal studies. On the other hand, computational simulations of the heart valve behavior have proven to be promising tools to enhance our understanding of the valvular mechanisms and response to pathological alterations [18, 19]. However, the existing computational models have yet to account for all the underlying features that impact the MV behavior.

The development of MV models has a long and productive history, with the first 3D finite element (FE) model of the MV described by Kunzelman et al. [20] in 1993. In that study, a simplified symmetric model that based on the few in-vitro physical measurements, including the regional thickness variations, collagen fiber architecture, and anisotropic material properties. Later studies by Prot et al. [21, 22] performed measurements on post-mortem porcine tissue to acquire geometric dimensions of the MV, and build a simplified model without the commissural regions and flat symmetric annulus. Votta et al. [23] built a more detailed model by including the saddle-shaped non-symmetric annulus using the ultrasound images. The leaflet surface was generated as a conical surface which qualitatively matched the echocardiography images. Maisano et al. [24] used the in-vitro measurements [25] to develop a geometric representation of the MV in the healthy state with symmetric leaflets and circular annulus. Skallerud et al. [26] used a 3D ultrasound imaging technique to extract the annular geometry, combined with the leaflet surface reconstructed from the post-mortem tissue. In parallel to the work on building MV models from the in-vitro data, several other researchers successfully built simplified models of MV from the in-vivo data. Lim et al. [27] reconstructed the MV geometry based on the end-diastole coordinates of transceiver crystals implanted on the MV annulus and free edge. The leaflets were assigned a constant thickness of 1.26 mm, even though the variations were measured from 0.5 mm in the leaflet belly to 2 mm in the trigons. Stevanella et al. [28] developed a patient-specific model of the MV based on the end-diastolic images acquired using cardiac magnetic resonance. They fitted spline curves to the outlines of the annulus and free edges, thus approximating the leaflet surface with the thickness map based on the values reported for post mortem tissue. Wang and Sun [29] based their analysis on the patient-specific multi-slice computer tomography images to extract a discretized representation of the MV leaflets with regional thickness values. This enabled them to develop a detailed leaflet structure with a realistic annular shape. Choi et al. [30] developed a patient-specific model of a MV with annular dilation based on 3D Trans-Esophageal Echocardiography (TEE) imaging. They simulated the MV ring annuloplasty by imposing an annuloplasty ring as a boundary condition. Pouch et al. [31, 32] developed a deformable template for the MV leaflet structure that allowed semi-automatic segmentation of in-vivo TEE images to build patient-specific models suitable for FE simulations. In another study, Witschey et al. [33] used the same framework to build quantitative virtual models of the MV under normal, ischemic, and myxomatous conditions.

Yet, these existing models rely on a limited subset of measurements or simplifications to reconstruct the MV geometry from imaging data [34, 35]. This issue is the direct result of the limitations of the existing imaging techniques, which cannot fully resolve the complete MV apparatus in-vivo, so that fine geometric features (e.g. the MVCT) are only partially resolvable. Consequently, MV computational simulations need to rely on the in-vitro imaging data to construct MV models [20, 21, 36, 37]. Furthermore, mechanical properties are customarily assigned globally, thus failing to account for the local variations of the tissue properties. The data on geometry, mechanical properties, and internal structure are also collected using different modalities (sometimes with very sparse data), so that existing methods for data assimilation are prone to mapping degeneracies and interpolation errors. New approaches to faithfully reconstruct the geometric details and embed tissue attributes are needed to improve the predictive power of the MV biomechanical models.

In our prior work [38], we developed the first high-resolution MV model that directly embedded key attributes at high resolution, such as full-field mapped collagen fiber architecture (CFA) data and robust material models for the leaflet and chordae. Extensive procedures were used to calibrate and validate the resulting computational solutions. Results of this study indicated appropriate parameter ranges and underscored the importance of structural “tuning” of the collagen structure for proper leaflet coaptation and natural functioning of the MV apparatus. While comprehensive and informative, there remains open questions as to the level of fidelity required in various clinical and scientific studies. This is particularly important in clinically-driven patient specific problems wherein high resolution information will in general not be available, and computational time is at a premium.

In the current study, we extended our original approach to develop a robust pipeline to build an attribute-rich computational model of MV with significantly higher level of geometric detail and fidelity of geometric reconstruction. Importantly, we extended the MV model pipeline to enable building of models with adjustable levels of detail and discretization. This allowed us to establish a framework for multi-resolution models of MV. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study of the development of validated multi-resolution attribute-rich computational models of the MV. In the following, we discuss the major processing steps, and illustrate the benefits of the proposed approach by building a single ovine MV model from in-vitro data.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data acquisition

A single, randomly selected MV image set was taken from the previous study which utilized micro-computed tomography (μCT) of ovine MVs in an in-vitro flow loop [39]. Briefly, freshly excised MV specimens from ovine hearts (from an USDA approved abattoir, Superior Farms, CA, USA) were selected based on the annular size of 30 mm. Prior to imaging, the leaflets were instrumented with ~100 high-contrast fiducial markers uniformly distributed to cover the full surface of both leaflets. The annulus was sutured to the adjustable annulus plate holder, which remained stationary during imaging, and could be easily adjusted to simulate different configuration (normal, dilated, and repaired). The annular dimensions in the normal and dilated states were taken from the previously published in-vivo data [40]. The dimensions of the normal annulus were set to 30×24 mm, and the dilated dimensions were 33×30 mm. The repaired annulus dimensions were set to be the same as for the normal annulus. PMs were attached to the adjustable rods, and the whole MV complex was mounted into Georgia Tech Cylindrical Left Heart Simulator (GT CLHS) [41].

This system was then installed into the pulsatile flow loop for hemodynamic tuning. The flow loop replicated the function of a healthy left ventricle with the flow parameters set to: pressure of 100 mmHg, flow rate of 5 L/min, and heart rate of 70 bpm. The positions of PMs were adjusted to achieve normal coaptation behavior defined as: (1) anterior leaflet occupying 2/3 of A2-P2 diameter, (2) coaptation length of 5mm, (3) no noticeable leakage measured in pressure and flow rate. The details of experimental setup and related experimental procedures can be found in [36, 38, 42, 43]. The MV was then imaged in three configurations that simulated: (1) normal (physiological), (2) dilated (the ischemic mitral regurgitation due to myocardial infarction), and (3) repaired (flat-ring annuloplasty repair) states. For the imaging of dilated and repaired configurations, the PMs were displaced to simulate the LV distension observed in the MVR patients as reported in [40, 44]. The posteromedial PM displacements were set to 4, 6, and 2 mm in the lateral, posterior, and basal directions, respectively. The displacement for the anterolateral PM were 2 mm laterally, 1 mm anteriorly, and 1.5 mm apically. Each specimen was imaged in two loading states for each of the considered configrations: end-diastolic (open, fully unloaded) and end-systolic (closed, fully pressurized) using a Siemens Inveon μCT scanner (Siemens Corp, Malvern, PA, USA). Since the radiopacity of MV tissue and water are very similar, all scans were performed in humidified air. The scan parameters were optimized for soft tissue: voltage of 80 keV, current of 500 uA, and resolution of 40 μm (isotropic voxels). The imaging time per scan was approximately 7 minutes and the resulting images stack was about 1200×1200×1200 voxels3.

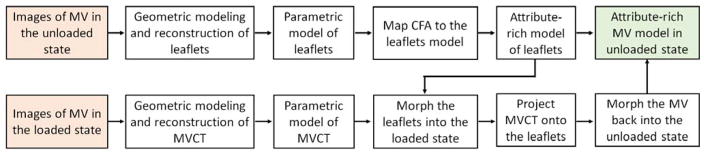

The structure of MV makes it difficult to capture the high-fidelity geometry of the MVCT and leaflets simultaneously in the same state. Specifically, in the end-diastolic state, the MVCT are loose and clump together, making it difficult to distinguish the individual branches (when imaged in humidified air chamber), whereas the leaflet geometry can be reconstructed with a high level of detail. Thus, reconstructing the MVCT geometry from this state would produce the geometry with underestimated level of branching, and exaggerated cross-sectional areas. In the end-systolic state, leaflets are in direct contact with each other, thus obstructing the extraction of boundaries of each leaflet surface. However, fine details of MVCT are more pronounced due to the tensioning of individual MVCT branches in this state. To address these issues, we reconstructed MVCT and leaflet geometries from two different states (Figure 1). End-systolic (loaded) scans were performed first, followed by the tissue fixation for the end-diastolic (unloaded) imaging. A solution of 0.5% glutaraldehyde was dripped over the MV tissues for two hours in the vertical closed loop fixation setup. This step was necessary to prevent shrinking of the leaflet tissue due to imaging in air and distortions caused by positioning of the GT CLHS into the μCT scanner. While this approach allows to capture high-fidelity geometry of MV structure, these geometric models cannot be directly used to perform biomechanical simulations of MV function. We co-register these two models to build full MV reconstructions in end-systolic and end-diastolic states.

Figure 1.

Overview of the major data processing states to build full attribute-rich MV model from two loading states.

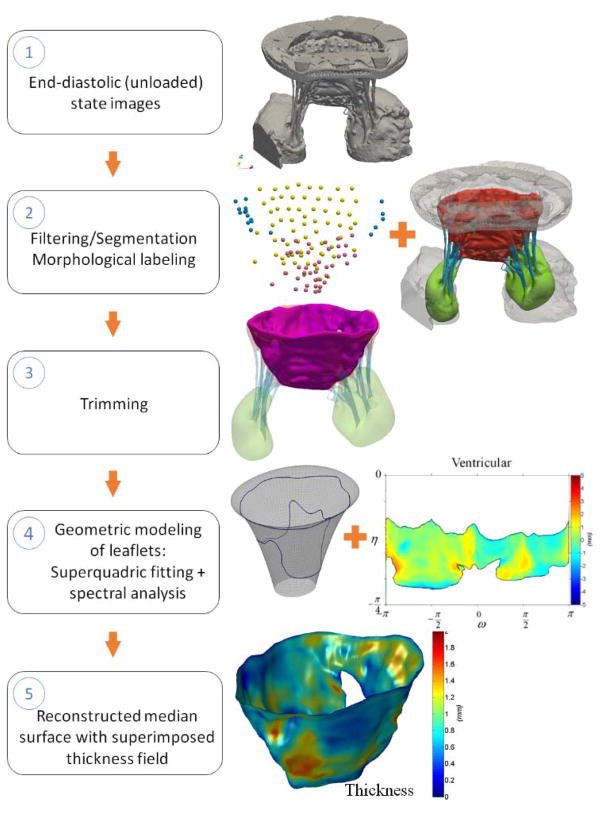

2.2. Image processing pipeline for end-diastolic state: reconstruction of the leaflet geometry

The main objective of processing imaging data from end-diastolic scan (open, fully unloaded state) was to extract MV leaflet geometry and fiducial markers. This pipeline (Figure 2) consists of the following major steps: (1) filtering and segmentation of raw imaging data, (2) trimming and morphological labeling, (3) extraction of leaflet tissue boundary surface geometry, (4) reconstruction of the leaflets using a two-scale model, and (5) mapping of fiducial markers onto the reconstructed model. The acquired imaging data was loaded as 32-bit DICOM images into ScanIP software package (Synopsis Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) for filtering and segmentation. We applied a diffusion-based curvature-flow filter [45] to reduce noise and improve contrast in the raw data prior to segmentation. The selected filter was run with the time-step of 0.0001 for the total of 100 iterations. The filtered dataset was segmented using an intensity-based thresholding operation at two different levels: one for the tissue segmentation and another value for fiducial markers segmentation. The choice of the optimal value for thresholding filter in both cases was chosen empirically by comparing the volume and level of roughness of the segmented volumes at 3–5 different levels.

Figure 2.

Major data processing steps necessary to reconstruct the leaflets geometry in unloaded state.

The endpoint of this pipeline is a parametric surface model with embedded thickness field.

The binary mask obtained from the segmentation filter was used to build the triangulated boundary surface representation using the marching cubes method [46]. The surface mesh was then imported into ZBrush 3D sculpting software package (Pixologic Inc., CA, USA) for extraction of leaflet tissue geometry. First, the geometric elements of CLHS were manually trimmed away by relying on two clearly defined landmarks: (1) the natural leaflet hinge line is sharp and easily distinguishable, allowing to separate out the annulus holder from the leaflet tissue; (2) the boundary between the CLHS annulus plate and leaflet tissue can be clearly identified. The trimmed geometry of MV was manually labeled to color-code the leaflet tissue, MVCT, and PMs. In the next step, we trimmed away MVCT together with the associated transition zones, thus extracting the leaflet tissue geometry. The artifacts from embedding the fiducial markers (localized peaks and valleys) were smoothed out using a local smoothing tool.

The trimmed boundary surface mesh was analyzed using the two-scale geometric model to generate a median surface representation as previously described in [36, 37, 47]. Briefly, the surface data was decomposed into two scales to decouple the general shape descriptor from the fine-scale features. The leaflets shape was modeled in the parametric form, while the missing details were captured as a set of discrete deviation fields from the primary model. We provide more details in Appendix 1.

We built a median surface by superimposing the SQ surface with the algebraic average of the atrial and ventricular deviation fields. A local thickness field, calculated as algebraic difference between these fields, was embedded onto the median surface to complete this representation. In the last step of this pipeline, we mapped the fiducial markers onto the reconstructed median surface. The segmented binary mask for fiducial markers was converted into the boundary surface mesh using the marching cubes algorithm. Individual markers were labeled using the topological mesh connectivity, and the corresponding marker centers were calculated as centers of mass of the triangulated meshes. The obtained marker centers were mapped onto the median leaflet surface using the closest point search algorithm. This procedure was repeated in several iterations with an increasing level of discretization of the SQ surface until the locations of footpoints converged. The endpoint of this pipeline is a parametric surface model with embedded thickness field.

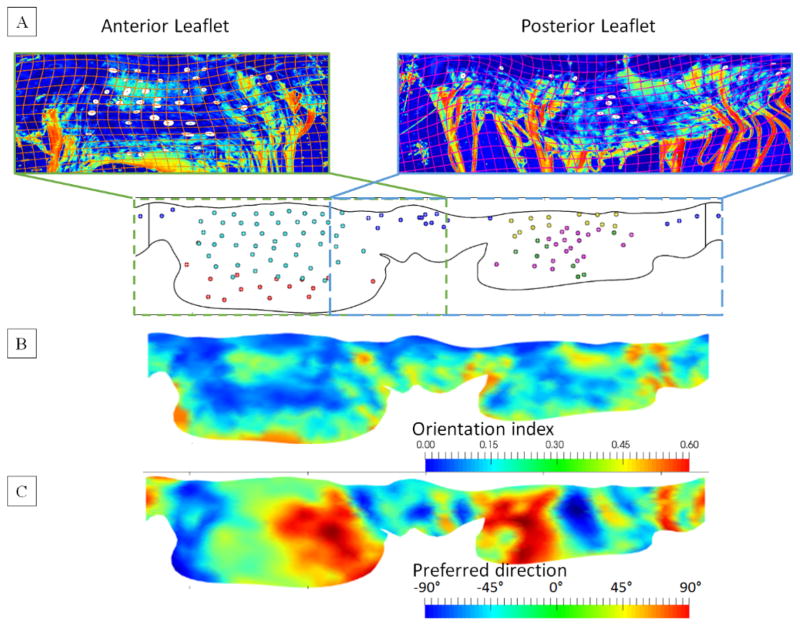

2.3. Mapping of the collagen fiber architecture data

After the micro-CT imaging protocol was completed, the MV specimens were fixed in the fully loaded state and dissected into anterior and posterior leaflets and mounted into the specially-designed fixture for CFA data collection. The local fiber architecture data was obtained using the small-angle light scattering (SALS) technique [48]. The measurements were analyzed to quantify the local effective fiber orientation distribution function (ODF) with the local preferred fiber direction and the degree of fiber splay by assuming the Gaussian distribution. The CFA data was then mapped onto the reconstructed leaflets surface using the elastic warping with fiducial markers as landmarks. This pipeline consisted of two major steps: (1) mapping of the marker locations onto the CFA images; (2) mapping of the CFA with markers onto the reconstructed leaflet surfaces.

In the first step, we manually segmented out the markers from the digital images of flattened and mounted leaflets prior to CFA measurements. The centers for each marker were calculated as ellipsoidal centers using software package FIJI [49]. The markers were mapped onto the CFA image using landmark-based elastic registration algorithm [50], which was implemented in “bUnwarpJ” module. The registered images of the markers were superimposed with the CFA images of anterior and posterior leaflets to obtain co-registered data needed for the next step. In the second step, the CFA data together with markers was mapped onto the unfolded surface of the leaflets using the same algorithm and implementation. The leaflets were unfolded in the SQ parametric space using the cylindrical projection (Figure 3). Upon registering both datasets, we stitched the data using a linear interpolation at the seam. In the final step, the continuous representation of the mapped CFA data was constructed and embedded onto the leaflet surface.

Figure 3.

(A) Mapping of the anterior (left) and posterior (right) CFA data onto the image of unfolded leaflets surface with co-registered fiducial markers. (B) The mapped and stitched continuous CFA data illustrated on the unfolded 2D representation of the leaflets.

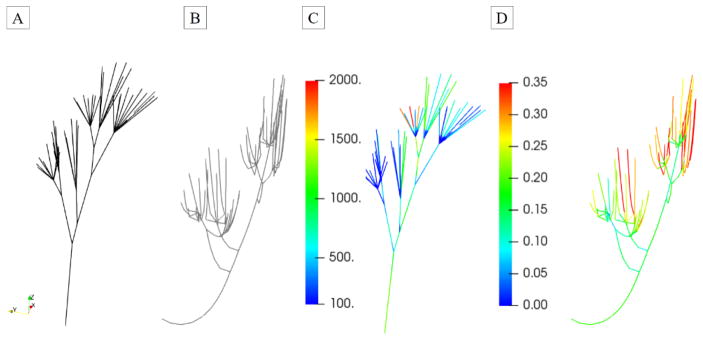

2.4. Image processing pipeline for end-systolic state: reconstruction of MVCT geometry

The imaging data from end-systolic scan (closed, fully loaded) was used to extract MVCT geometry and fiducial markers. The major steps (Figure 4) included filtering and segmentation, trimming and labeling of individual MVCT bundles, extraction of centerlines, and reconstruction of MVCT using a parametric model. We followed the same procedure for filtering, segmentation, and reconstruction of the surface boundary mesh as described in Section 2.2. The triangulated surface mesh was manually labeled to partition leaflets, MVCT, and PMs from CLHS. The resulting mesh was trimmed once again to cut away PM and leaflet tissues, thus extracting the individual MVCT bundles.

Figure 4.

Major data processing steps necessary to reconstruct the MVCT geometry in the loaded state. The endpoint of this pipeline is a parametric truss model with embedded pointwise CSA field.

Given that the topology of MVCT is similar to that of branching tubular structures, these geometries can be efficiently represented using the curve-skeleton models [51]. We used the Centerline module in ScanIP software to develop smooth skeletonized representation of MVCT. Smooth skeletonization curves of MVCT were enriched with smooth CSA data to build an isoparametric smooth curve-skeleton representation (specifically, 3-rd order B-spline) of MVCT bundles. It is important to note that at this stage, the geometric model of MVCT bundles had arbitrarily defined origins (start locations at PMs) and insertions (end locations at leaflets). We observed that even though there was not distinguishable anatomical landmark to precisely define origins and insertions, all of the extracted MVCT bundles exhibited noticeable flaring (transition zones) around those locations. To address this issue, we analyzed the variations of CSA values and defined a criterion to systematically trim the MVCT skeletonizations. We relied on the rate of change in CSA values (dimensionless ratio of equivalent radius of MVCT to the arc length along the MVCT) with the threshold value set at 0.15. The details of this procedure can be found in [52]. In the last step of data processing of end-diastolic scan data, we extracted fiducial markers following the same procedure as described in Section 2.3. The triangulated boundary surface mesh was analyzed to label individual markers, and extract the centers of mass. The combined data on the locations of fiducial markers from loaded and unloaded states was used to perform reconstruction of the leaflets in the loaded state, as discussed in the following.

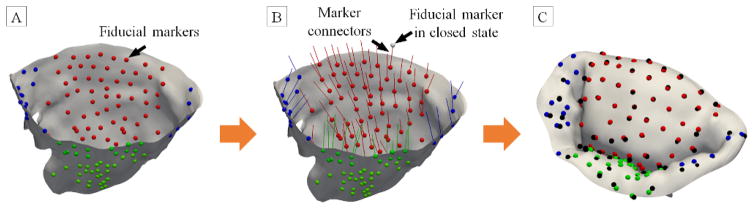

2.5. Landmark registration of leaflet surface between end-diastolic and end-systolic scans

Due to the issues with reconstructing the leaflets geometry directly from the fully loaded state images (see Section 2.1), we performed morphing of the leaflet surface from the unloaded to the loaded state using iterative 3D landmark registration. This approach allowed us to establish bijective (one-to-one) mapping between material points on the leaflet surface in the two imaged states by iteratively building correspondence between fiducial markers in the two states. We formulated the mapping problem as elastic morphing of leaflets from the end-diastolic into the end-systolic state.

We chose to implement morphing using a hyperelastic FE model because this approach imposes physically-based regularization as follows: (1) all morphing solutions are bijective by definition, (2) only kinematically admissible solutions are allowed, (3) the excessive (unphysical, no gaps or tears allowed) localized deformations are minimized due to the form of the strain energy function. We used a commercial FE software package ABAQUS 6.14.1 (SIMULIA, Dassault Systèmes, Providence, RI, USA) configured to use a nonlinear (Newton-Raphson) quasi-static solver with direct explicit time integration (explicit central difference scheme) and automatic time stepping. The convergence criteria were set to 0.01 in relative displacements and 0.0001 in relative residuals. The leaflets geometry was discretized using first-order isoparametric triangular elements and assigned shell element type (ABAQUS type S3) with element-wise thickness field. The MVCT geometry was discretized using the first-order isoparametric line elements and assigned uniaxial truss element type (ABAQUS type T3D3) with element-wise cross-sectional areas.

The mechanical behavior of leaflet tissue was simulated using a nearly-incompressible transversely isotropic simplified structural model (SSM) introduced by Fan and Sacks [53]. The model is formulated as a two-component composite: collagen fibers and the non-fibrous hydrated matrix. The total strain energy function, ψ, is given by

| (1) |

where Ψf and Ψm are the effective collagen fiber and matrix strain energies, respectively, Γ(θ) is the collagen fiber orientation distribution function, Ψens is the collagen fiber ensemble strain energy density function, Eens = n(θ)TEn(θ) is the ensemble fiber strain in the n(θ) direction, E = (C − I)/2 is the tissue-level Green–Lagrange strain tensor, C = FTF is the right Cauchy–Green deformation tensor, F is the deformation gradient tensor, and I is the identity tensor. Further, μM is the matrix Neo-Hookean material model constant, responsible for bulk low-strain response, I1 = trace(C), J1 = det(F), and p is the Lagrange multiplier to enforce incompressibility. The resulting leaflet total second Piola–Kirchhoff stress tensor is

| (2) |

where is the direct consequence of imposing incompressibility condition in planar tissues, p = −μm C33 is the Lagrange multiplier. To simplify computations, we chose an exponential model to simulate the highly nonlinear fiber ensemble stress-strain response [53] as

| (3) |

where c0, c1 are the material constants described in Table 1, and Eub is the threshold fiber strain for full collagen fiber recruitment.

Table 1.

Material model coefficients for leaflets and MVCT.

| Model name | μm, kPa | c0, kPa | c1 | Eub |

| Leaflets | 10.11 | 0.0485 | 24.26 | 0.37 |

| C10, kPa | C01 | Eub | ||

| Chordae | 100 | 13.7 | 0.31 |

The displacements of fixed-edge (annulus) were prescribed in all directions to replicate the experimental constraints, as the MV annulus was sutured to the stationary annulus holder. We guided the morphed shape to accurately match the strain distribution of the imaged leaflet geometry by weakly imposing the displacements of the fiducial markers. Specifically, we defined the pre-loaded elastic springs with ends of each spring connecting the locations of the fiducial markers in the open and closed states. The equilibrium state of these springs (zero force) would be achieved when the markers move from the open to the closed state. Based on the prior sensitivities studies, we set the spring stiffness to 0.02 N/mm. In other words, a marker location mismatch of 5 mm would produce a point force of 0.1 N. In contrast to explicitly prescribing the displacement fields for the fiducial markers, this approach reduced the influence of errors associated with calculating the marker centers.

As an initial guess, we chose pressure loading of leaflets to estimate the shape of leaflets and locations of fiducial markers in the end-systolic state. Using the results of this simulation, marker correspondence pairs were identified using the nearest neighbor search algorithm (finding of the closest points by the shortest geometric distance), followed by manual adjustments/cleanup. At each next iteration, we applied the identified correspondence pairs as boundary conditions and re-ran morphing simulations until all markers were registered. The quality of morphing and validity of correspondence pairs were evaluated by monitoring the local area distortions (determinant of the deformation gradient). The correspondence pairs and morphed leaflet surface after two iterations are illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Major processing steps involved in the landmark-based hyperelastic warping of leaflets from the unloaded to the loaded states. The reconstructed leaflets with co-registered fiducial markers are illustrated in (A). The correspondence map between the fiducial markers in unloaded and loaded states are shown in (B). The warped surface of leaflets in the fully loaded state are presented in (C) with the markers from loaded state images shown in gray. The averaged error between the predicted and imaged locations of the markers is 0.2 mm.

2.6. Complete reconstruction of MV in end-diastolic and end-systolic states

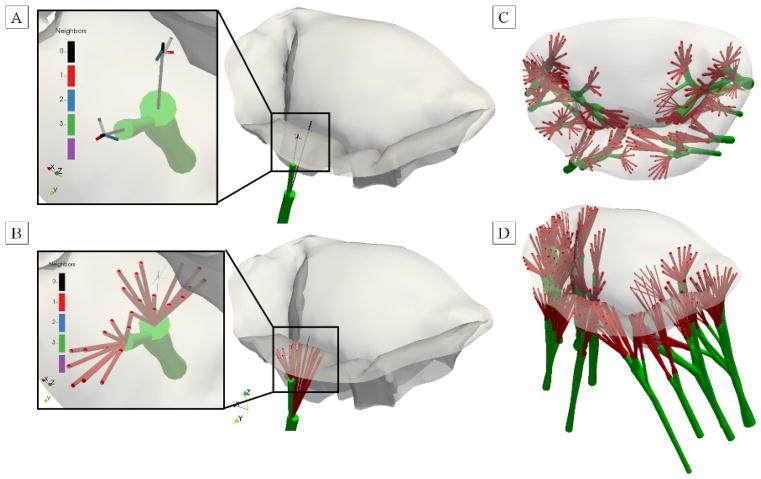

Registration of the leaflet surfaces to the end-systolic state provided a reconstruction of all components of MV in the same state. However, the connection between MV leaflet surface and MVCT was missing because both MVCT and leaflet surface were trimmed to exclude transition zones. We attached MVCT to the leaflet surface by performing linear extrapolation of the insertion branches [52] until the intersection with the leaflet surface. The missing information on CSA values in those regions was extrapolated via a prescribed flaring function (constant rate of change in CSA equal to the cut-off threshold value). Complete MV reconstruction in the end-systolic state with interconnected leaflets and MVCT is illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Combining the leaflets and MVCT models in the loaded state. (A) projection of terminal points of MVCT branches onto the leaflets surface by linear extension and nearest neighbor search. (B) The transition of MVCT into leaflets is built by connecting the nodes in the vicinity of the insertion location at the specified flaring radius. The complete model of MVCT with leaflets (gray), MVCT (green) and transition zones (red) are shown from (C) top and (D) perspective views.

Next, we morphed MVCT to the end-diastolic state by applying the open-closed deformation map to the insertions (points attached to the leaflet surface). We implemented morphing as FE simulation following a similar procedure as described in Section 2.5. The MVCT geometry was discretized using the first-order isoparametric line elements and assigned uniaxial truss element type (ABAQUS type T3D3) with element-wise cross-sectional areas. All MVCT elements were assigned elastic material properties with a high stiffness modulus. Gravity loading was added to simulate the imaging conditions in the end-diastolic state. The solver parameters were set to the same values as described in Section 2.5. The choice of stiff morphing allowed us to recover a functionally equivalent geometry of the MVCT in the open state. In other words, if we were to perform a closing simulation of the MV with stiff MVCT at this stage, the predicted shape of both leaflets and MVCT would match the morphed shape obtained in the previous step. Next, we need to introduce realistic material properties of MVCT through calibration and embedding of the pointwise pre-strain field.

2.7. Calibration of the MVCT pre-strain

Having the geometrically equivalent MVCT was not sufficient to run realistic simulations of MV closing behavior as this model was only accurate under the assumption of inextensible MVCT tissue properties. To address this issue, we performed a calibration step with realistic material properties of MVCT. The mechanical behavior of MVCT tissue was simulated using an incompressible isotropic hyperelastic material model with the following constitutive equation

| (4) |

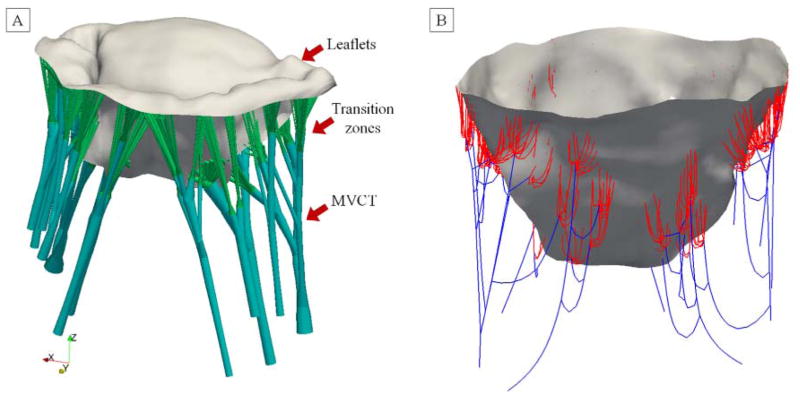

where is the uniaxial strain in MVCT, and C10 and C01 are the material constants (Table 1). Knowing that the inextensible MVCT model can accurately reproduce the geometry of a fully loaded MV, we performed a closing simulation under the boundary conditions mimicking the experimental setup: a stationary annulus and PMs with prescribed motion vectors, and a uniform pressure loading of 100 mmHg. This simulation provided the information on the distribution of forces in each of the MVCT branches, which we converted into the map of pointwise stresses. Having the material model coefficients and the map of pointwise stresses fully defined, we inverted the stress-strain relationship to obtain the map of the effective pre-strain field for each MVCT element. This step allowed us to obtain the reference geometry of the MVCT with realistic material properties and the required functional behavior. The endpoint of this processing step was a complete reconstruction of MV in the loaded and unloaded states (Figure 7). The details of the calibration procedure are discussed in the Appendix 3.

Figure 7.

(A) The final MV model in the loaded visualized with 3D reconstruction of MVCT and transition zone. (B) the calibrated reference MV model in the unloaded state with MVCT and transition zone visualized as truss FE.

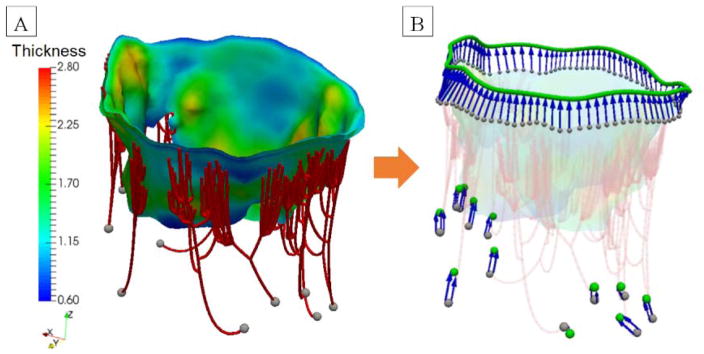

2.8. FE methodology for a case study: coaptation simulation of MV

We performed FE simulation of MV coaptation under constant pressure loading to illustrate the flexibility and advantages of using the proposed image-based model for biomechanical simulations. This case study replicated the in-vitro conditions used for imaging the end-systolic state of MV. This allowed us to compare the predicted and the imaged geometries of the leaflets and MVCT. A commercial FE software package ABAQUS Explicit was configured to use a nonlinear quasi-static solver with direct time integration (explicit central difference scheme) and automatic time stepping. The solver parameters and details of the simulation configuration were presented in Sections 2.5 and 2.7. The loading conditions were prescribed to simulate the experimental conditions: stationary annulus and PMs with prescribed motion vectors and constant trans-ventricular pressure of 100 mmHg. The motion of the PMs and annulus (Figure 8) were imposed due to the inherent compliance of the experimental setup. The leaflet surfaces were loaded using a prescribed pressure boundary condition applied to the ventricular faces. Contact interaction between the anterior and posterior leaflets was simulated as frictionless self-contact boundary condition.

Figure 8.

(A) FE model of MV in the unloaded state with superimposed thickness field. The gray spheres represent the locations of origin points of MVCT. (B) the displacement boundary conditions applied to the annulus and PM nodes are visualized as blue arrows. Gray spheres represent original locations of the nodes, green spheres correspond to the displaced locations.

2.9. Post-processing of the simulation results

As an extension of the approach described in Fan and Sacks [53], we developed the following total fiber recruitment tensor to provide insight into the deformations and structural response of leaflet tissue microstructure under the mechanical loading, defined as

| (5) |

where Γ(θ) is the fiber orientation distribution function, D(χ) is the fiber ensemble recruitment function, and Eens is the fiber ensemble strain. This is an important indicator of the tissue-level response of the leaflets under different loading conditions. The magnitude of χ is a normalized index of local structural changes in the leaflet tissue, which varies between zero (slack tissue with full structural reserve) and 1.0 (fully recruited tissue with depleted structural reserve). The choice of the tensorial formulation instead of the single scalar index, provides a deeper insight into the directional tissue response.

2.10. Validation and sensitivity studies

In the effort to assess the predictive power of the developed model, we performed simulations which reproduce pathological (dilated) and interventional (repaired) states of MV. The dimensions of the dilated annulus were set to 33×30 mm, and the repaired dimensions were set to 30×24 mm (the same as the normal annular dimensions). In both dilated and repaired states, the PMs were displaced to simulate the LV distension observed in the MVR patients with displacements of 4, 6, and 2 mm in the lateral, posterior, and basal directions, respectively. The displacement targets for the anterolateral PM were set to 2 mm laterally, 1 mm anteriorly, and 1.5 mm apically. The accuracy of the model was quantified by comparing the predicted and actual fiducial marker displacements. For each of the simulated states, we analyzed the distributions of the following quantities of interest: circumferential and radial strains and stresses, and circumferential and radial components of χ.

Next, we leveraged the flexibility of our approach to build FE models with adjustable levels of detail and discretization to investigate the sensitivity of the predictions to the model parameters. We performed a series of simulations by individually adjusting (1) the level of detail, (2) the level of discretization, (3) level of complexity of the material model, (4) calibration procedure for MVCT. To put the assessment of the simulation results on a more quantitative level, we developed the following composite accuracy score (CAS)

| (6) |

where k is index of the quantity of interest, i is the FE index and N is the total number of elements in the model, qi,k is the values of quantity of interest in the considered model, q̄i,k is the quantity of interest in the reference model, σi,k is the standard deviation of the quantity interest in the reference model. This score provides a single value representing the average accuracy of the predictions with respect to the reference model in terms of all of the considered quantities of interest. The upper bound is 1 which corresponds to the perfect match to the reference model, and all values lower than 1 correspond to degrading quality of the predictions.

3. Results

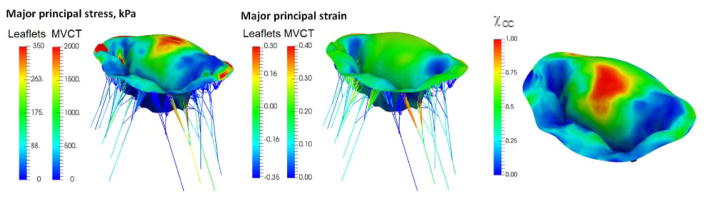

Following the processing steps described in Section 2, the filtered imaging data was segmented to build a complete attribute-rich computational model of MV. This model was used to simulate the normal physiological state (Figure 9). This loading case was used for model calibration to adjust the level of prestrain in the leaflet and MVCT tissue. The objective of calibration was to minimize the errors in predicted locations of fiducial markers and associated surface strains. We found that the average errors were ±0.2 mm in the normal state.

Figure 9.

Simulation results for the normal state: (A) major principal stress, (B) major principal strain, (C) χCC. The observed distribution of elevated levels of stresses, TFR and strains was observed in the center of the anterior leaflet in all of the considered models.

Next, to investigate the sensitivity of predictions to the choice of model parameters, we built a series of models by varying the number of different parameters of the model: level of detail and discretization, complexity of the material model, calibration of MVCT (Table 2). In terms of level of detail, we considered the range starting from a fully-featured model represented by 100×100 Fourier coefficients, down to a model with only 10×10 Fourier coefficients. This range of parameters corresponds to the spatial filtering of the features from the scale of 1 mm to 10 mm (Figure 10). With regards to the level of discretization, we built models at the full level of detail with the element size of 1.0 mm (MM1), down to 0.4 mm (MM2) (Figure 11). The material model complexity was also varied from the fully mapped CFA data with anisotropic behavior (FM) down to the prescribed uniform values of CFA and isotropic behavior (MAT1) (Figure 12). The calibration procedure for MVCT was varied form the fully mapped pre-strain field for each point in the model (FM) down to the uniform value of pre-strain obtained from the overall reaction force (MVCT1) in the model (Figure 13). Furthermore, we also investigated the differences in the predicted shape of the leaflets by interrogating several lateral cross-sections (Figure 14).

Table 2.

Model nomenclature and parameters. “Level of detail” refers to the threshold of the low-pass filter used to reconstruct the leaflets surface features, thickness field and CFA data; “level of discretization” is the average FE mesh size; “mapped CFA” refers to the heterogeneous distribution of pointwise CFA data; “prescribed CFA” refers to the homogeneous distribution of CFA with prescribed value of splay and the preferred direction aligned with the circumferential direction.

| Model name | Level of detail | Level of discretization | Material model | CFA | MVCT calibration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

| Models with varying levels of details | |||||

| MR1 | 20 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

| MR2 | 10 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

| MR3 | 5 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

| MR4 | 2 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

| Models with varying levels of discretization | |||||

| MM1 | 0.4 mm | 0.95 mm | anisotropic | Mapped | full |

| MM2 | 0.4 mm | 0.45 mm | anisotropic | Mapped | full |

| Models with varying levels of material model fidelity | |||||

| MAT1 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | isotropic | prescribed | full |

| MAT2 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | prescribed | full |

| MAT3 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | prescribed | full |

| Models with different MVCT calibration approaches | |||||

| MVCT1 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | avg. stress |

| MVCT2 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | avg. force |

| MVCT3 | 0.4 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | mapped | avg. reaction |

| Models with varying levels of overall fidelity (all of the parameters are adjusted simultaneously) | |||||

| LOW1 | 10 mm | 0.95 mm | isotropic | prescribed | avg. force |

| LOW2 | 10 mm | 0.95 mm | isotropic | prescribed | full |

| MED1 | 5 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | prescribed | avg. force |

| MED2 | 5 mm | 0.6 mm | anisotropic | prescribed | full |

| HIGH | 0.4 mm | 0.45 mm | anisotropic | mapped | full |

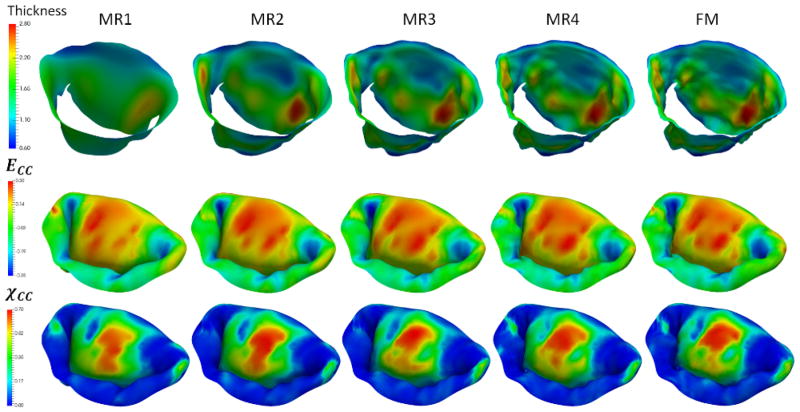

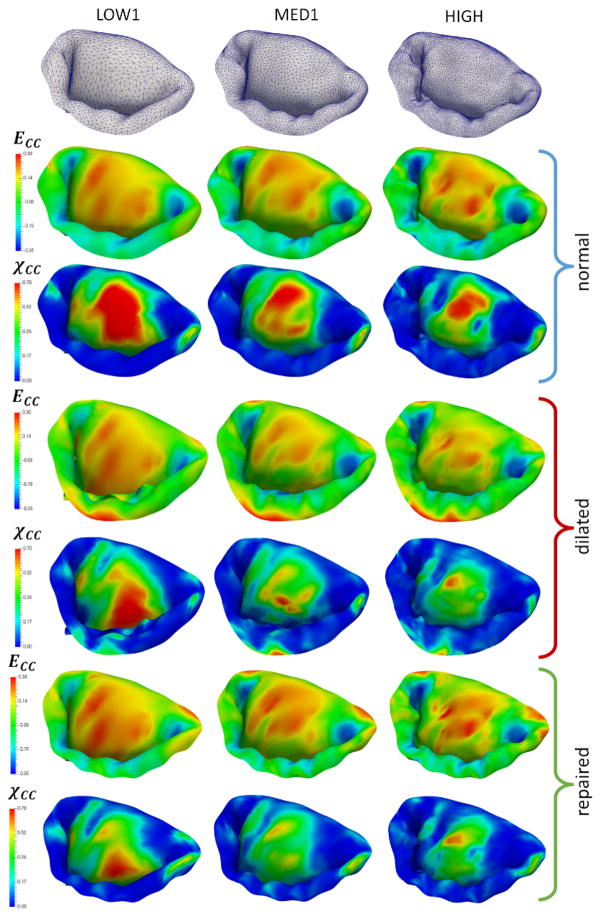

Figure 10.

Reconstructions of the leaflet geometry with varying levels of detail. The second and the third rows provide the predicted distributions of circumferential strains and χCC. Notice that the strain distribution does not vary much, however, the distribution of χCC shows the significant differences between the considered models.

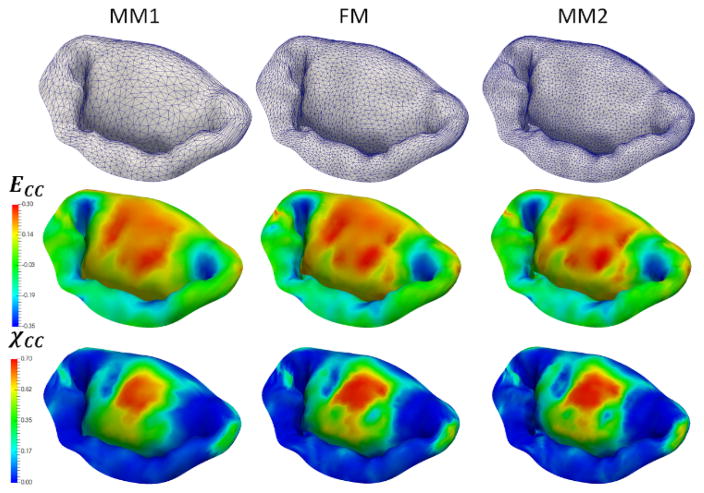

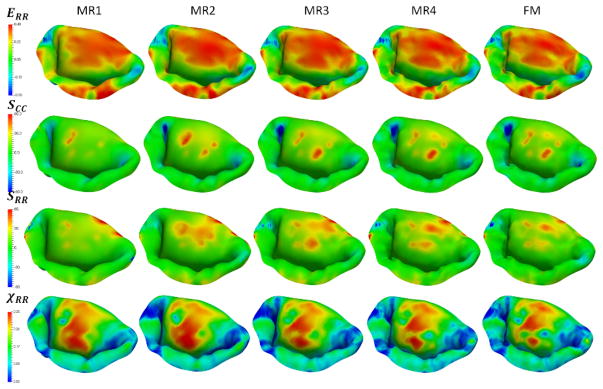

Figure 11.

Sensitivity study results for different levels of discretization. All of the considered models show very similar predictions in the stress, strain and χCC values, demonstrating that these level of discretization are sufficient to capture MV behavior.

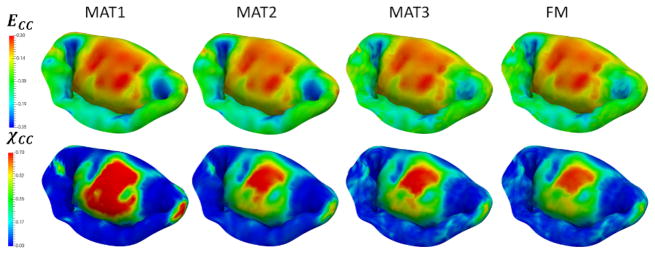

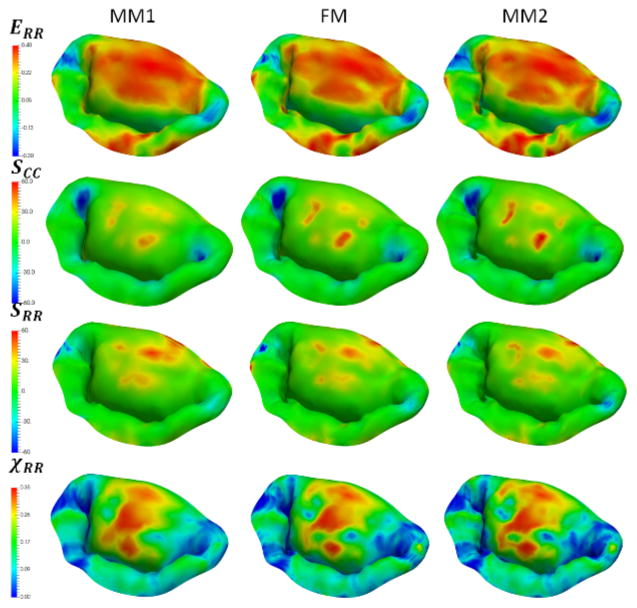

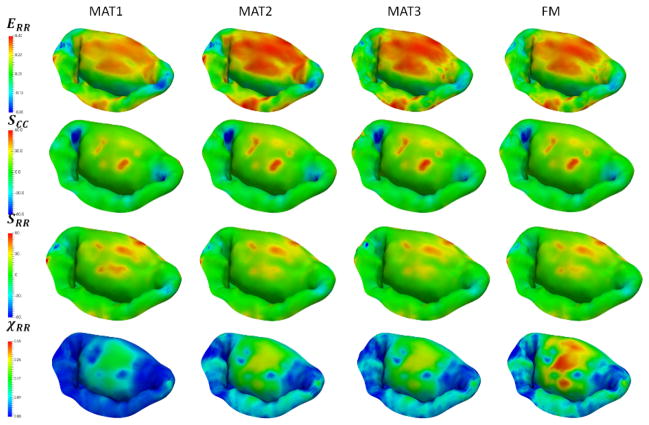

Figure 12.

Sensitivity study results for different choices of material models. Notice a large difference between the isotropic (MAT1) and anisotropic models (MAT2-4). The differences in having a predefined homogenous set of material properties (MAT2 and MAT3) and a fully mapped CFA data (FM) are not very significant.

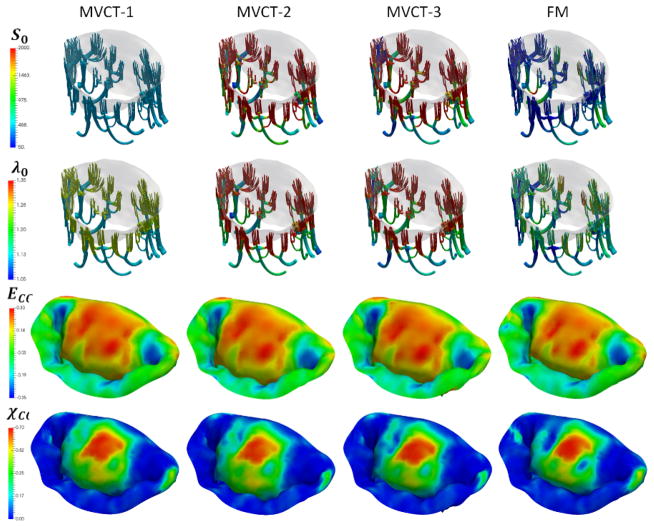

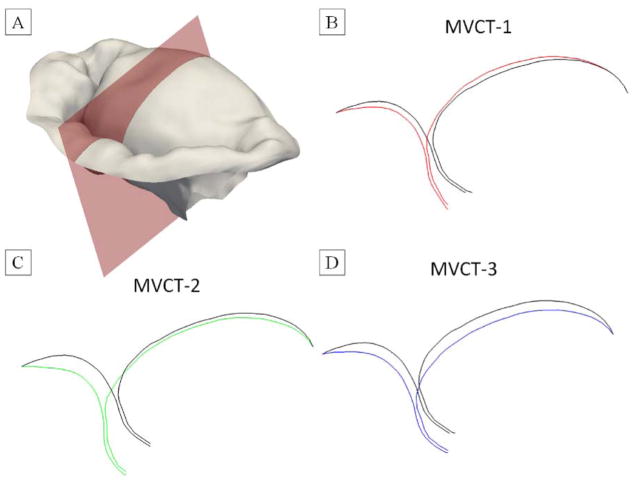

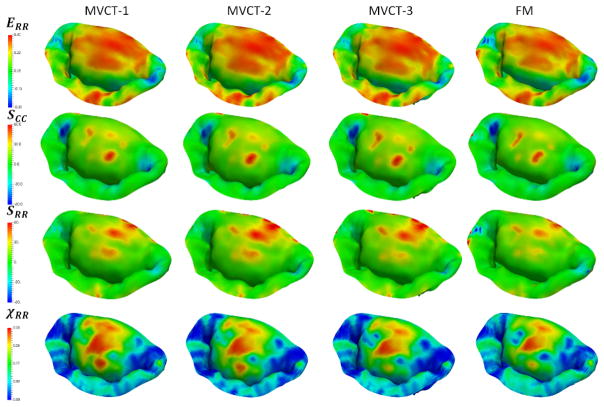

Figure 13.

Sensitivity study results for different choices of MVCT calibration: MVCT-1 was calibrated using the overall reaction force in the PM origins. MVCT-2 was calibrated using the average tension in each individual MVCT bundle, MVCT-3 was calibrated using the average stress in each individual MVCT bundle, FM relied on the full pointwise pre-strain. We did not observe significant differences in the distributions of stresses, strains and TFR values, even though there was a noticeable difference in the predicted shape of the leaflet surfaces.

Figure 14.

The differences in the predicted shape of the leaflets for different MVCT calibration methods: (A) visualization of the cutting plane to generate slice images, (B) MVCT-1 was calibrated using the overall reaction force in the PM origins; (C) MVCT-2 was calibrated using the average tension in each individual MVCT bundle; (D) MVCT-3 was calibrated using the average stress in each individual MVCT bundle. Colored contours illustrate the predicted shape from the considered model, black contours represent the predicted shape from FM model.

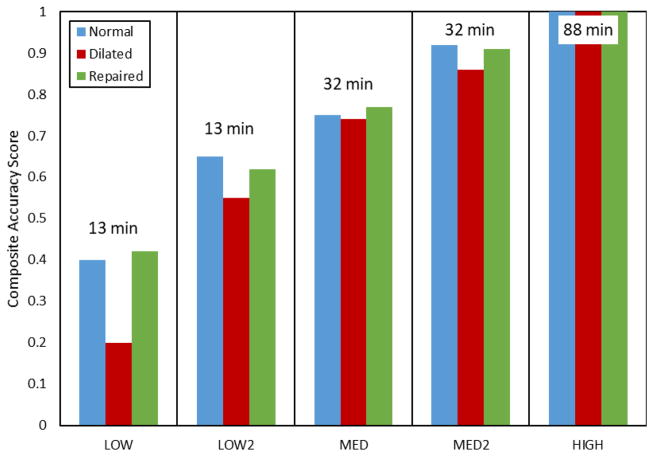

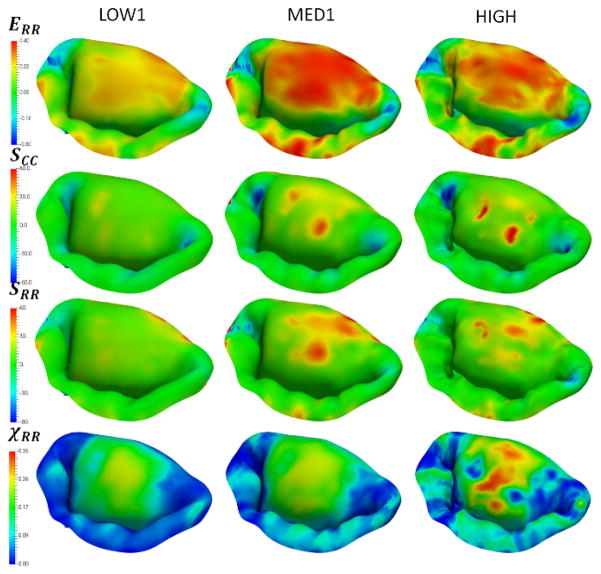

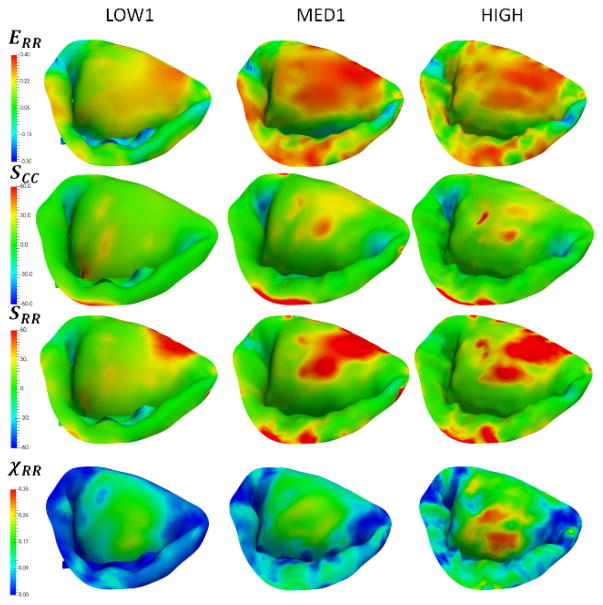

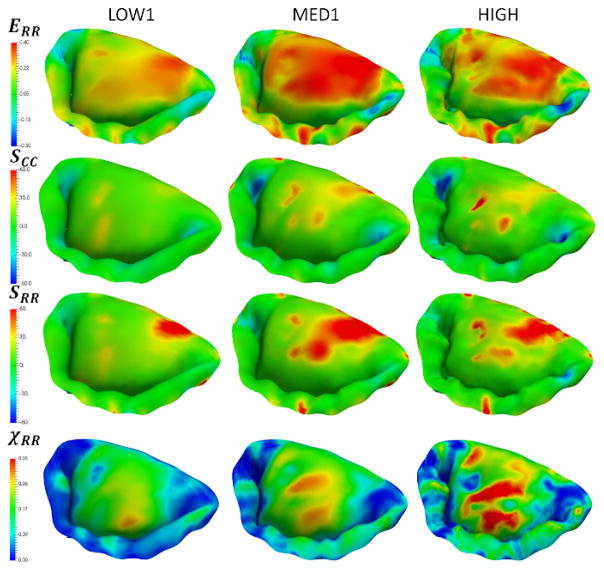

In the effort to investigate the combined effect of varying all of the considered parameters, we built five additional models (LOW1, LOW2, MED1, MED2, HIGH). These models were used to simulate the normal, dilated and repaired scenarios (Figure 15). The accuracy of the model was quantified by comparing predicted and actual fiducial marker displacements, and calculating the CAS values (Figure 16). We found that the model LOW1 failed to accurately predict the dilated state, while all of the other models provided relatively good predictions with the accuracy of the predicted values progressively increasing with the increase in the level of model fidelity.

Figure 15.

Simulations of the normal, dilated and repaired MV states using three models with varying levels of complexity. Notice that the predictions of circumferential strains are not very sensitive to the choice of the model, while the predicted values of χCC. show noticeable differences between the LOW1, MED1 and HIGH.

Figure 16.

Comparison of the accuracy of predictions and computational costs for the considered models. The labels on top of each column represent the computational time required to complete the simulation using a single-threaded solver. The differences between LOW1/LOW2 and MED1/MED2 are only in the choice of the calibration method for MVCT. With the exception of the LOW1 predictions for dilated states, all other models show gradual increase in the accuracy of predictions with the increasing complexity of the model.

4. Discussion

4.1. Major observations

We have developed an approach for building multi-resolution, attribute-rich computational models of the MV apparatus, and demonstrated its utility in predicting biomechanical response of MV under different physiological and pathological states. Our approach provides robust segmentation and parametric reconstruction of leaflets with adjustable levels of detail (via spectral filtering) of fine scale geometric features and adjustable level of discretization. Both features provide significant advantages in building the image-based models for numerical simulations. Notably, this approach enables comprehensive sensitivity studies of the levels of detail and discretization on the predictive capability of the model. Furthermore, this approach solves both parameterization and registration problems, thus facilitating statistical analysis of different MV specimens in a systematic manner. The proposed methodology also provides a streamlined pipeline for reconstructing MVCT geometry with a high level of fidelity and adjustable level of detail. The proposed method of embedding CSA information in the isoparametric representation allows for a high degree of flexibility in building computational models.

An important contribution of this work is the capability to capture the fine geometric details of both leaflets and MVCT with high-fidelity by combining imaging data from end-systolic and end-diastolic states. Furthermore, the proposed approach is generally insensitive to imaging data noise. We incorporated the information from both imaged states through landmark-based morphing, resulting in two co-registered reconstructions of complete MV geometry. In comparison to our prior work [38], we (1) increased the level of detail in reconstruction of leaflets; (2) switched to the use of end-systolic state for reconstruction of MVCT; (3) utilized 3× lower number of fiducial markers; (4) performed full reconstruction of both states; (5) developed parametric model instead of discretized fixed-resolution reconstruction.

Another important feature of the proposed model is that our parametric representation provides C∞ smoothness of leaflet reconstruction due to the inherent properties of the Fourier reconstruction, and C2 smoothness of MVCT model due to the choice of 3rd degree splines for reconstruction. High-level of smoothness enables building of high-fidelity FE models using high-order Lagrangian and novel isogeometric formulations. Compact parametric representation also facilitates efficient archiving of the imaging data: in our case, raw imaging data (DICOM) consists of the image stack with size of 10243 voxels (5,000MB), the segmented triangulated boundary surface (binary STL format) consists of 3M triangles (200MB). The reconstructed model reduces the representation (binary data file) to about 10,000 parameters (0.1MB). Furthermore, adding new states to the reference model requires only a compact parametric deformation field with size of about 1,000 parameters or 0.01 MB.

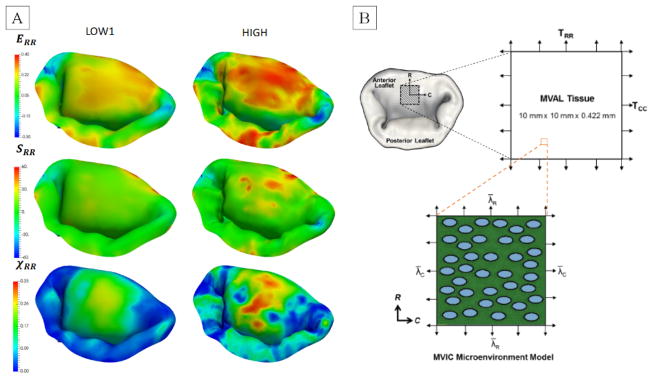

In addition to the proposed framework for building geometric model of MV from imaging data, we also developed a pipeline for embedding tissue attributes into the reconstructed geometry. We illustrated the advantages of this approach by building an attribute-rich FE model of a complete MV. This is an important feature for building consistent multi-resolution models required in parametric studies and optimization frameworks. Having the capability of easily switching from low-resolution models to high-resolution high-fidelity models is relevant in such applications as surgical planning, virtual surgery simulators, and medical device design. For example, the same model can be used in the low-resolution mode in virtual surgery simulator, allowing for realtime interaction, and in the high-resolution mode for the development of medical design prototype. This is important that while there were minor differences observed in the S and ERR (Figure A3, see Appendix), the radial fiber recruitment component (χRR) showed substantially more fiber recruitment with increasing fidelity. While this difference in predictions would not be a significant factor in describing the overall behavior of MV at the organ level (Figure 17), it would significantly affect the predictions of local cellular response of the tissue. We investigated the link between the organ-level strains and their effect on the cellular mechanics in our prior work [54] and found that there is a strongly nonlinear relationship between organ-level and cellular level responses, and therefore it is important to provide accurate predictions of the local tissue strain state. This result suggests that while organ-level simulations can utilize simplified material models, multi-scale studies will need greater material model fidelity.

Figure 17.

(A) Illustration of the key differences in the predictions of the stresses, strains, and fiber recruitment values between the low fidelity and high fidelity models. (B) Relationship between the tissue and cellular responses in the MV leaflets (modified and reproduced from [54]) through downscale modeling approach.

We evaluated the robustness of the proposed model through sensitivity studies of levels of model fidelity. This allowed us to identify which model parameters had the strongest effect on its predictive capability. The presented results demonstrated that the level of geometric detail and complexity of the material model had a minor effect on the organ-level predictions of the stress and strain distributions. However, it was critical to use a detailed calibration procedure and accurately establish the MVCT reference geometry. This effect can be clearly seen in the comparison of the predictions between LOW1/LOW2 and MED1/MED2 models. Those model pairs differ only in the choice of the calibration method for MVCT (simplified pre-tension based on the reaction force vs full-field pre-strain field). Overall, the considered models exhibited a gradual increase in the accuracy of predictions with the increasing complexity of the model, with the only exception being the predictions of LOW1 (isotropic material model with minimal level of details and global pre-tension in the MVCT) for the dilated state.

Our simulation results also provide insight into the biomechanics of the MV function under different physiological states. The observed distributions of stresses and strains reveal significant differences in the MVCT and leaflet tissues response under three different loading scenarios (Figure 15). Specifically, we observed the redistribution of the MVCT forces between the branches and regions of highest stresses within the leaflets. The χ tensor revealed drastic differences in the level of microstructural rearrangements in the leaflets between the three considered scenarios. The distribution of the regions with depleted structural reserve (fully recruited fibers) vary drastically between the states, and allow us to quantify the effect of the disease progression, and eventual repair on the leaflets microstructure.

Lastly, we note that our model provides a unique insight into the leaflet - MVCT interactions. Specifically, the boundary conditions for normal and repaired states prescribe the same annulus shape and pressure loading, with the only difference in the locations of PM origins: PMs remain in the dilated positions in the repaired state. The strain levels in the leaflets and MVCT in the normal and repaired states show significant differences, thus demonstrating the importance of high-fidelity modeling of MVCT in predicting leaflet tethering. The structural tensor index (χ) revealed a similar trend in the structural response of collagen fibers in the leaflets. We observed a much more pronounced recruitment of collagen fibers in the center region of the anterior leaflets in the repaired state compared to the other simulated states. All these metrics combined can guide future repair strategies to take into account cellular level response to the surgical interventions, and potentially reduce the recurrence rates of MVR.

4.2. Limitations

The presented approach is illustrated by building an attribute-rich computational model of MV from in-vitro images with calibration and validation based on in-vitro measurements. Even though we applied this methodology to with the goal to consistently build and analyze the biomechanical responses of patient-specific data, it is not obvious whether the same level of predictive power would be achieved with in-vivo data. Specifically, our model does not include the contractile motion of the MV annulus, and the motion of PMs due to ventricular dynamics throughout the cardiac cycle. The proposed formulation also ignores the fluid-structure interaction, thus limiting the applicability of this approach to investigating only fully loaded and unloaded states. However, we believe the fully–loaded systolic state will provide the most meaningful state for fidelity comparisons, which was faithfully reproduced here.

The leaflet tissue response was simulated using a simplified structural model which provided insight into the tissue-level response and structural rearrangement. However, this model lacks capability to account for the complex multilayer microstructure and composition variations of the MV leaflet tissue [55]. The mapping of the CFA data is a necessary step which can only be achieved in an in-vitro setting. We address this issue, we are currently working on building a library of CFA data for a population of ovine MVs, which eventually will be used to generate a representative CFA distribution for in-vivo simulations. In terms of predicting in-vivo biomechanical response of the MV to disease and repair, this study does not take into account the tissue growth and remodeling processes. To better understand the biomechanical response of the tissue, the model needs to be extended to accurately model these phenomena. Furthermore, in order to elucidate the mechanobiological drivers of the growth and remodeling, it is important to connect the organ-level tissue response to the cellular-level response. This would enable us to investigate the changes in phenotypic state of MV interstitial cells and analyze their response to the mechanical stress overloads and surgical interventions.

4.3. Future work

Having a consistent mesh-independent attribute-rich representation of the MV can enable rigorous statistical analysis of patient-specific models, and inform the development of population-averaged representative models. We plan to investigate the effect of the attributes and geometric parameters on the MV function in individual MVs and in a population using population-averaged metrics. The proposed approach is the first step towards the long-term goal of reducing the number of negative outcomes associated with the IMR repairs. We are working on extending this work to building computational models of human MVs from in-vivo (preclinical) medical imaging data. This work will also encompass the studies of important shape parameters in the AP ring design and optimization of the AP ring shape.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL119297 to MSS. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Nomenclature

- 2D-DFT

2D Discrete Fourier Transform

- CSA

Cross Sectional Area

- CFA

Collagen Fiber Architecture

- CLHS

Cylindrical Left Heart Simulator

- LV

Left Ventricle

- μCT

Micro Computed Tomography

- MVCT

Mitral Valve Chordae Tendineae

- MVR

Mitral Valve Regurgitation

- ODF

Orientation Distribution Function

- PM

Papillary Muscle

- SALS

Small-Angle Light Scattering

- SQ

Superquadric

- SSM

Simplified Structural Model

- TEE

Trans-Esophageal Echocardiography

- χ

Total Fiber Recruitment Tensor

APPENDICES

Appendix 1 – Detailed description of the geometric model for leaflets

The trimmed boundary surface mesh was analyzed using the two-scale geometric model to generate a median surface representation, see [36, 37, 47]. The leaflets shape was modeled in the parametric form, while the missing details were captured as a set of discrete deviation fields from the primary model. We chose the superquadric (SQ) model [56, 57] as the shape model, which allowed us to register different valves and normalize their dimensions. SQs are a family of generalized quadric shapes, which allow for flexible description of a large number of concave and convex objects, including ellipsoids, hyperboloids, spheres, etc. In Cartesian coordinates, SQ surface is represented by the following implicit equation

| (7) |

where a1, a2, and a3 are shape parameters that control the size of the superquadric shape along x, y, and z directions, respectively. The parameters ε1 and ε2 are the so-called squareness factors, which regulate the surface curvature in the xy-plane and along the z-axis, correspondingly. In this particular case, SQ is a good shape descriptor because the general shape of the MV leaflets in the open state is very similar to the hyperboloid surface with ellipsoidal cross-section. Having the single fitted SQ surface allowed us to partition the boundary surface mesh of the leaflets into atrial and ventricular surfaces with two shared edge boundaries: fixed edge (annulus) and free edge.

The fine-scale features were extracted as a set of signed deviations from the fitted SQ surface. We relied on orthogonal projection to find the footpoints on the SQ surface for embedding this information into the large-scale model. Thus, the SQ surface enriched with the scalar field of orthogonal deviations provided an exact representation for atrial and ventricular surfaces. This representation easily lends itself to applying spectral analysis and obtaining a compact sparse representation with adjustable levels of detail (low-pass filtering in spectral space) and discretization (sampling of spectral data onto the SQ surface). We relied on 2D discrete Fourier transform (2D-DFT) to obtain the spectral representation of the scalar deviation field. Specifically, signed-distance fields were reconstructed using

| (8) |

where fA (η,ω) and fV (η,ω) correspond to the atrial and ventricular scalar deviation fields, respectively. The in-plane coordinate variables η = sin−1[(z/a3)1/ε1] and ω = tan−1[[(y/a2)/(x/a1)]1/ε2] are the parametric coordinates of the SQ surface. The parameters βA and βV are the Fourier coefficients. The classical 2D-DFT formulation requires the input data to be provided on a structured uniform rectangular grid. To address this issue, we developed a novel approach for analyzing surface data on unstructured triangulated meshes with irregular boundaries, which is discussed in detail in [36, 47].

Appendix 2 – Detailed description of the geometric model for MVCT

We used the Centerline module in ScanIP software to develop smooth skeletonized representation of MVCT. In their implementation, the morphology thinning filter is applied to extract discrete centerline points from the imaging data, followed by the iterative pruning to remove small artifacts. In the next step, the raw centerlines were used to build approximating B-spline curves with a specified level or average error (we set error tolerance to 2 voxels or 80 μm). The B-spline parametric representations have the following form

| (9) |

where Ni,3(u) is the degree-3 B-spline basis function corresponding to the ith control point Pi. The range of summation denotes the number of control points for each curve, which was varied to achieve the specified error tolerance. Next, having the smooth parametric curves representing the skeleton of MVCT bundles, the pointwise cross-sectional areas (CSA) information was extracted by interrogating triangulated boundary surface mesh along the curves with the stepping size of 1 voxel or 40 μm. In the next step, the tabulated CSA values were processed using self-written scripts in Python to build B-spline smooth representation with a relative error tolerance set to 1%. Finally, smooth skeletonization curves of MVCT were enriched with smooth CSA data to build an isoparametric smooth curve-skeleton representation (specifically, 3-rd order B-spline) of MVCT bundles.

Appendix 3 - Calibration procedure for determining the level of pre-strain in MVCT

In order to accurately establish the level of pre-strain (or equivalently, reference configuration) in MVCT, we performed “stiff” closing simulations to recover the realistic levels of stresses in MVCT. This information was then used to invert the stress-strain relationship and arrive at the pointwise field of the MVCT pre-strain. Specifically, the fully coapted model of MV was morphed into the unloaded (open) state using the previously established full field deformation map for leaflets. Due to lack of the deformation map for the MVCT, the morphing step was performed using stiff material model (100× stiffer than the actual material model) with all elements subjected to the gravity load to emulate the conditions of the imaged state. These two conditions allowed to effectively recover the open-state “pose” of the imaged MV without changing the length of individual branches of the MVCT. In the next step, we performed a closing simulation of the MV to determine the effective pre-strain in MVCT. The leaflets were subjected to the uniform pressure loading and the MVCT were modeled using the same “stiff” material model. At this stage, each of the MVCT elements was tensioned with realistic stresses. This information allowed us to recover the corresponding strain levels by inverting the actual material model of MVCT. We populated the open-state model with these pre-strain values and re-run the closing simulation using the realistic MVCT material model to verify the accuracy of the calibration step.

Figure A1.

Major steps in calibration of the MVCT: (a) reconstructed geometry of MVCT in the fully loaded state; (b) morphed geometry using “stiff” material model in the unloaded state; (c) predicted geometry in the closed state with superimposed plot of stresses in kPa; (d) MVCT geometry in the open state with super-imposed field of pre-strains.

Appendix 4 – Additional simulation results

We provide here additional simulation results to illustrate the differences and the observed patterns in the sensitivity studies (Figures A2–A5) and predictions of models with different levels of fidelity (Figures A6–A8). In terms of level of detail, we considered the range starting from a fully-featured model represented by 100×100 Fourier coefficients, and reducing the level of detail down to a model with only 10×10 Fourier coefficients. This range of parameters corresponds to the spatial filtering of the features from the scale of 1 mm to 10 mm. With regards to the level of discretization, we built models at the full level of detail with the element size of 1.0 mm (MM1), down to 0.4 mm (MM2). The material model complexity was varied from the fully mapped CFA data with anisotropic behavior (FM) to the prescribed uniform values of CFA and isotropic behavior (MAT1). The calibration procedure for MVCT was varied form the fully mapped pre-strain field for each point in the model (FM) down to the uniform value of pre-strain obtained from the overall reaction force (MVCT1) in the model.

Figure A2.

Additional plots from the sensitivity study of the effects of varying the levels of detail. Notice that the strain and stress distributions does not vary much, however, the distribution of χRR exhibit noticeable differences between the considered models.

Figure A3.

Additional plots from the sensitivity study of the effects of different levels of discretization. Notice that the distributions for the considered quantities of interest do not vary much.

Figure A4.

Additional plots from the sensitivity study of the different choices of material models. Notice a large difference between the isotropic (MAT1) and anisotropic models (MAT2-4). The differences in having a predefined homogenous set of material properties (MAT2 and MAT3) and a fully mapped CFA data (MAT4) are not very significant for all of the considered quantities of interest except for the χRR.

Figure A5.

Additional plots from the sensitivity study of the different choices of MVCT calibration. We did not observe significant differences in the distributions of stresses, strains and χRR values, even though there was a noticeable difference in the predicted shape of the leaflet surfaces.

Figure A6.

Additional plots from the simulations of the normal MV using three models with varying levels of complexity. Notice that the predictions of radial stresses, strains and χRR exhibit noticeable differences between the LOW1, MED1 and HIGH.

Figure A7.

Additional plots from the simulations of the dilated MV using three models with varying levels of complexity. Similarly to the normal state, notice that the predictions of radial stresses, strains and χRR exhibit noticeable differences between the LOW1, MED1 and HIGH.

Figure A8.

Additional plots from the simulations of the repaired MV using three models with varying levels of complexity. Similarly to the normal state, notice that the predictions of radial stresses, strains and χRR exhibit noticeable differences between the LOW1, MED1 and HIGH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Van Mieghem NM, et al. Anatomy of the mitral valvular complex and its implications for transcatheter interventions for mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(8):617–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madesis A, et al. Review of mitral valve insufficiency: repair or replacement. Journal of Thoracic Disease. 2014;6(Suppl 1):S39–S51. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.10.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tibayan FA, et al. Geometric distortions of the mitral valvular-ventricular complex in chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2003;108(10 suppl 1):II-116–II-121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087940.17524.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vergnat M, et al. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: a quantitative three-dimensional echocardiographic analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;91(1):157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.d’Arcy J, et al. Valvular heart disease: the next cardiac epidemic. Heart. 2011;97(2):91–93. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.205096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedrazzini GB, et al. Mitral regurgitation. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(3–4):36–43. doi: 10.4414/smw.2010.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enriquez-Sarano M, Akins CW, Vahanian A. Mitral regurgitation. The Lancet. 2009;373(9672):1382–1394. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60692-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kheradvar A, et al. Emerging Trends in Heart Valve Engineering: Part I. Solutions for Future. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2015;43(4):833–843. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1209-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kheradvar A, et al. Emerging trends in heart valve engineering: Part III. Novel technologies for mitral valve repair and replacement. Ann Biomed Eng. 2015;43(4):858–70. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1129-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunberger E, et al. Very long-term results (more than 20 years) of valve repair with carpentier’s techniques in nonrheumatic mitral valve insufficiency. Circulation. 2001;104(12 Suppl 1):I8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David TE, et al. Late outcomes of mitral valve repair for mitral regurgitation due to degenerative disease. Circulation. 2013 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000699. CIRCULATIONAHA. 112.000699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rausch MK, et al. Mitral valve annuloplasty: a quantitative clinical and mechanical comparison of different annuloplasty devices. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40(3):750–61. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0442-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Acker MA, et al. Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(1):23–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bothe W, Miller DC, Doenst T. Sizing for mitral annuloplasty: where does science stop and voodoo begin? The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;95(4):1475–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouma W, et al. Saddle-Shaped Annuloplasty Improves Leaflet Coaptation in Repair for Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;100(4):1360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouma W, et al. Preoperative Three-Dimensional Valve Analysis Predicts Recurrent Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation After Mitral Annuloplasty. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;101(2):567–75. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.09.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flameng W, et al. Durability of mitral valve repair in Barlow disease versus fibroelastic deficiency. J Thorac Cardiovas Surg. 2008;135(2):274–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandran KB. Role of Computational Simulations in Heart Valve Dynamics and Design of Valvular Prostheses. Cardiovasc Eng Technol. 2010;1(1):18–38. doi: 10.1007/s13239-010-0002-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kheradvar A, et al. Emerging trends in heart valve engineering: Part iv. computational modeling and experimental studies. Annals of biomedical engineering. 2015;43(10):2314–2333. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1394-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunzelman KS, et al. Finite element analysis of the mitral valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 1993;2(3):326–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prot V, Haaverstad R, Skallerud B. Finite element analysis of the mitral apparatus: annulus shape effect and chordal force distribution. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology. 2009;8(1):43–55. doi: 10.1007/s10237-007-0116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prot V, Skallerud B. Nonlinear solid finite element analysis of mitral valves with heterogeneous leaflet layers. Comput Mech. 2009;43(3):353–368. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Votta E, et al. Mitral valve finite-element modelling from ultrasound data: a pilot study for a new approach to understand mitral function and clinical scenarios. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2008;366(1879):3411–34. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2008.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maisano F, et al. An annular prosthesis for the treatment of functional mitral regurgitation: Finite element model analysis of a dog bone–shaped ring prosthesis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2005;79(4):1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunzelman KS, et al. Anatomic basis for mitral valve modelling. J Heart Valve Dis. 1994;3(5):491–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skallerud B, Prot V, Nordrum IS. Modeling active muscle contraction in mitral valve leaflets during systole: a first approach. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2011;10(1):11–26. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim KH, Yeo JH, Duran CM. Three-dimensional asymmetrical modeling of the mitral valve: a finite element study with dynamic boundaries. J Heart Valve Dis. 2005;14(3):386–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevanella M, et al. Mitral valve patient-specific finite element modeling from cardiac MRI: application to an annuloplasty procedure. Cardiovas Eng Tech. 2011;2(2):66–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, Sun W. Finite Element Modeling of Mitral Valve Dynamic Deformation Using Patient-Specific Multi-Slices Computed Tomography Scans. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(1):142–153. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi A, et al. A novel finite element-based patient-specific mitral valve repair: virtual ring annuloplasty. Bio-medical materials and engineering. 2014;24(1):341–347. doi: 10.3233/BME-130816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pouch AM, et al. Development of a semi-automated method for mitral valve modeling with medial axis representation using 3D ultrasound. Med Phys. 2012;39(2):933–50. doi: 10.1118/1.3673773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pouch AM, et al. Semi-automated mitral valve morphometry and computational stress analysis using 3D ultrasound. J Biomech. 2012;45(5):903–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Witschey WR, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound-derived physical mitral valve modeling. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(2):691–4. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.04.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammer PE, et al. Medical Imaging. International Society for Optics and Photonics; 2008. Image-based mass-spring model of mitral valve closure for surgical planning. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prot V, et al. On modelling and analysis of healthy and pathological human mitral valves: two case studies. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2010;3(2):167–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khalighi AH, et al. Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart. Springer; 2015. A comprehensive framework for the characterization of the complete mitral valve geometry for the development of a population-averaged model; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drach A, et al. Population-Averaged Geometric Model of Mitral Valve From Patient-Specific Imaging Data. Journal of Medical Devices. 2015;9(3):030952. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CH, et al. On the effects of leaflet microstructure and constitutive model on the closing behavior of the mitral valve. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10237-015-0674-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.!!! INVALID CITATION !!!

- 40.Daimon M, et al. Dynamic change of mitral annular geometry and motion in ischemic mitral regurgitation assessed by a computerized 3D echo method. Echocardiography. 2010;27(9):1069–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabbah JP, Saikrishnan N, Yoganathan AP. A novel left heart simulator for the multi-modality characterization of native mitral valve geometry and fluid mechanics. Ann Biomed Eng. 2013;41(2):305–315. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0651-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siefert AW, et al. In vitro mitral valve simulator mimics systolic valvular function of chronic ischemic mitral regurgitation ovine model. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;95(3):825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bloodworth CHt, et al. Ex Vivo Methods for Informing Computational Models of the Mitral Valve. Ann Biomed Eng. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vergnat M, et al. Ischemic mitral regurgitation: a quantitative three-dimensional echocardiographic analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(1):157–64. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malladi R, Sethian JA. Image processing via level set curvature flow. proceedings of the National Academy of sciences. 1995;92(15):7046–7050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.15.7046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lorensen WE, Cline HE. ACM siggraph computer graphics. ACM; 1987. Marching cubes: A high resolution 3D surface construction algorithm. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khalighi AH, et al. Multi-resolution models for the mitral valve image-based simulations. Medical image analysis. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sacks MS. Small-angle light scattering methods for soft connective tissue structural analysis. Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schindelin J, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9(7):676–82. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]