Abstract

The so-called amyloid hypothesis, that the accumulation and deposition of oligomeric or fibrillar amyloid β (Aβ) peptide is the primary cause of Alzheimer's disease (AD), has been the mainstream concept underlying AD research for over 20 years. However, all attempts to develop Aβ-targeting drugs to treat AD have ended in failure. Here, we review recent findings indicating that the main factor underlying the development and progression of AD is tau, not Aβ, and we describe the deficiencies of the amyloid hypothesis that have supported the emergence of this idea.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Aβ, APP, amyloid, tau, PHF

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is said to account for about 70% of dementia. The affected brain exhibits astroglyosis, nerve cell atrophy and neuronal loss, and is characterized by the extensive distribution of two kinds of abnormal structures: so-called senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). In the 1980's, it was shown that senile plaque consists of amyloid fibrils composed of the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide (Glenner and Wong, 1984; Masters et al., 1985), while NFT contain bundles of paired helical filaments of the microtubule-associated protein tau by immunochemically (Brion et al., 1985; Grundke-Iqbal et al., 1986; Nukina and Ihara, 1986) and biochemically (Goedert et al., 1988; Kondo et al., 1988; Kosik et al., 1988; Wischik et al., 1988b).

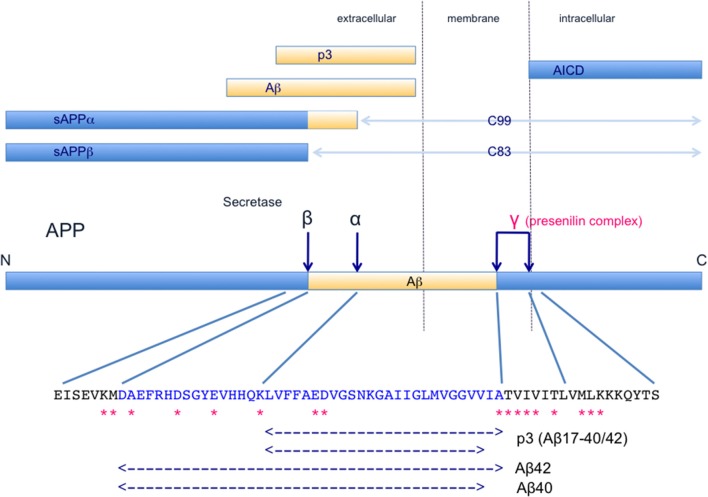

Aβ is a peptide consisting of about 40 amino acids, formed by sequential cleavages of amyloid β precursor protein (APP, http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P05067) by β-secretase (BACE 1) and γ-secretase (a complex containing presenilin 1), as illustrated in Figure 1. APP is a transmembrane protein associated with neuronal development, neurite outgrowth, and axonal transport (Kang et al., 1987). On the other hand, tau is a microtubule-associated protein that promotes microtubule polymerization and stabilization, and the abilities are regulated by phosphorylation (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P10636).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the structure and metabolism of APP and its derivatives. Dark blue arrows indicate cleavage sites. α-Secretase (TACE/ADAM) (Buxbaum et al., 1998; Lammich et al., 1999) cleaves the α-site and β-secretase (BACE1, Vassar et al., 1999) cleaves the β-site, affording N-terminal fragments, sAPPα and sAPP β, and C-terminal fragments, C83 and C99, respectively. C83 and C99 are further cleaved at the γ-sites by γ-secretase complex, which includes presenilin-1, nicastrin, Aph-1 and Pen2 (Capell et al., 1998; De Strooper et al., 1998; Yu et al., 2000; Francis et al., 2002; Goutte et al., 2002; Takasugi et al., 2003). AICD and p3/Aβ are produced and released from the membrane. In the normal physiological state, α-secretase cleaves 90% or more of APP and the remaining APP is cleaved by β-secretase. Therefore, the major products in this APP metabolic pathway are sAPPα, C83, p3, and AICD, and Aβ is a minor product. AICD is rapidly degraded (Cupers et al., 2001; Kopan and Ilagan, 2004; Kametani and Haga, 2015). Thus, mutations found in familial AD, especially presenilin mutations, may affect the formation and processing of a variety of products. A part of APP sequence including Aβ is shown. Asterisks indicate APP mutations that have been identified in familial AD. These pathogenetic mutations of APP cluster near the α-secretase, β-secretase and γ-secretase cleavage sites. These mutations cause accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments (Tesco et al., 2005; Wiley et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2016a), and such accumulation has been found even in sporadic AD brains (Pera et al., 2013). Furthermore, mutations in presenilin, a constitutive protein of the γ-secretase complex, reduce γ-secretase activity (Chen et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2005; Bentahir et al., 2006; Shen and Kelleher, 2007; Xia et al., 2015). Decrease in the catalytic capacity of γ-secretase, which would lead to an increase of APP C-terminal fragments, facilitates the pathogenesis in sporadic and familial AD (Svedruzic et al., 2015).

Studies of AD pathogenesis have mostly been focused on how Aβ and tau form senile plaques and NFTs, respectively, and how these abnormal structures induce neural degeneration and neuronal loss.

The amyloid hypothesis

The amyloid hypothesis (also known as the amyloid cascade hypothesis, the Aβ hypothesis, etc.) has been the mainstream explanation for the pathogenesis of AD for over 25 years (Hardy and Allsop, 1991; Selkoe, 1991; Hardy and Higgins, 1992; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002), and may be briefly summarized as follows (Figure 1). In normal subjects, Aβ is excised from APP by β- and γ-secretase and released outside the cell, where it is rapidly degraded or removed. However, in aged subjects or under pathological conditions, the metabolic ability to degrade Aβ is decreased, and Aβ peptides may be accumulated. Aβ 40 and Aβ 42 (more hydrophobic than Aβ 40), containing 40 and 42 amino acid residues, respectively, are major components of the accumulated Aβ (Figure 1). An increase in the level of Aβ 42 or an increase in the ratio of Aβ 42 induces Aβ amyloid fibril formation, and the accumulated Aβ amyloid fibrils develop into senile plaque, causing neurotoxicity and induction of tau pathology, leading to neuronal cell death and neurodegeneration.

The APP gene is on chromosome 21 (Kang et al., 1987), and the discovery of genetic mutations of APP in early-onset familial AD (http://www.alzforum.org/mutations), as shown in Figure 1, appeared to support the amyloid hypothesis. These pathogenetic mutations of APP are clustered near β-secretase or γ-secretase cleavage sites, and are associated with an increase in Aβ42 production and/or a change in the ratio of Aβ42 formation. Interestingly, Down's syndrome patients with trisomy 21 exhibit AD-like pathology by about 40 years of age (Kolata, 1985), and this was thought to be due to the fact that the amount of APP in the brain was increased to 1.5 times the normal amount and the amount of Aβ was also increased (Kolata, 1985). In addition, APP locus duplication causes autosomal-dominant early-onset AD with cerebral amyloid angiopathy, with accumulation of large amounts of Aβ peptides (Delabar et al., 1987; Rovelet-Lecrux et al., 2006). Moreover, other familial AD mutations have been identified in presenilin 1/2, which is a component of γ-secretase (http://www.alzforum.org/mutations) (Figure 1). These mutations in APP and presenilin are closely linked to the Aβ production process, providing a rational basis for the idea that Aβ production and/or Aβ amyloid fibril formation represent the central pathogenic cause of AD (Hardy and Allsop, 1991; Selkoe, 1991; Hardy and Higgins, 1992; Hardy and Selkoe, 2002).

Problems with the amyloid hypothesis

To investigate the pathogenesis of AD, a number of genetically modified mouse models were produced in which Aβ is deposited in the brain. However, although senile plaques (accumulation of Aβ amyloid fibrils) are formed in these mice, NFT formation (accumulation of tau) and nerve cell death have not been observed (Bryan et al., 2009) (http://www.alzforum.org/research-models/alzheimers-disease). This suggested that extracellular accumulation of Aβ fibrils is not intrinsically cytotoxic, and also that Aβ does not induce tau accumulation. As Aβ is a normal metabolic product of APP and is not itself toxic under normal physiological conditions, the idea developed that Aβ oligomers (multimers) were the key toxic agents.

It has been reported that synaptic failures occur from an early stage in the AD brain and that the levels of synaptic proteins change (Masliah et al., 2001). Also, a drastic decrease in the number of synapses is characteristically observed in AD (Davies et al., 1987). Therefore, it was suggested that Aβ, which is present abundantly at an early stage after birth in AD model mice, causes synaptic impairment (William et al., 2012). Furthermore, it was reported that decrease of dendritic spines, inhibition of long-term potentiation, promotion of long-term suppression, and impairment of memory learning occur when Aβ oligomers (dimers) obtained from AD patients' brains were directly transferred to hippocampus of mouse brain (Shankar et al., 2008). However, although Aβ oligomers and Aβ amyloid fibrils were present in Aβ42-overexpressing BRI2-Aβ mice, and amyloid deposits and formation of senile plaques were observed in the brain, degeneration of nerve cells and neuronal loss were not observed, and there was no impairment of cognitive functions (Kim et al., 2007, 2013). These results indicate that Aβ42, including its oligomers and amyloid fibrils, is not cytotoxic. In addition, various immunotherapies targeting Aβ in AD model mice were effective in decreasing Aβ deposition in the brains, but it did not lead to improvement of actual symptoms or accumulation of tau (Ostrowitzki et al., 2012; Giacobini and Gold, 2013; Doody et al., 2014; Salloway et al., 2014).

Recent advances in amyloid imaging have made it possible to observe Aβ amyloid accumulation in the patient's brain. As a result, it has been found that there are many normal patients with amyloid deposits, and also AD patients with very few amyloid deposits (Edison et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008). Further, in the brain of elderly non-demented patients, the distribution of senile plaques is sometimes as extensive as that of dementia patients (Davis et al., 1999; Fagan et al., 2009; Price et al., 2009; Chetelat et al., 2013). This suggests that Aβ amyloid deposition is a phenomenon of aging, and has no direct relation with the onset of AD.

Taking these facts into account, it appears that neurodegeneration/neuronal loss and amyloid deposition are independent, unrelated phenomena (Chetelat, 2013), contrary to the amyloid hypothesis.

Reconsideration of APP and presenilin (PS) mutations in familial AD

In this section, we will focus on the nature and effects of mutations that are reported to be associated with familial AD.

In the normal physiological state, α-secretase cleaves 90% or more of APP and the remaining APP is cleaved by β-secretase, then γ-secretase cleaves the C-terminal region, as shown in Figure 1. The major products of this APP metabolic pathway are sAPPα, C83, p3, and APP intracellular domain (AICD), and Aβ is a minor product. Moreover, AICD is rapidly degraded (Cupers et al., 2001; Kopan and Ilagan, 2004; Kametani and Haga, 2015), suggesting that APP C-terminal fragments (C83, C99, and AICD) may be toxic and need to be removed (Kametani, 2008; Robakis and Georgakopoulos, 2014). Thus, when considering the effects of familial AD mutations, the effects on all the major products of APP metabolism should be considered.

AD-associated mutations in PS (PS1), a constituent protein of the γ-secretase complex, reduce γ-secretase activity, leading to decreased production of Aβ, especially Aβ40 (Chen et al., 2002; Walker et al., 2005; Bentahir et al., 2006; Shen and Kelleher, 2007; Xia et al., 2015). But, as a result, the proportion of Aβ42 increases and Aβ amyloid is formed. At the same time, APP C-terminal fragments that should be cleaved by γ-secretase are not cleaved, and accumulate in the cell membrane (Chen et al., 2002; Kametani, 2008; Robakis and Georgakopoulos, 2014).

It has also been reported that APP mutation causes accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments (Tesco et al., 2005, p.181; Wiley et al., 2005, p. 205; Xu et al., 2016a) and that the production of APP C-terminal fragment by β-secretase increases in the brain of patients with sporadic AD (Pera et al., 2013). Moreover, decrease in the catalytic capacity of γ-secretase, which would promote accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments, might facilitate the development of both sporadic and familial AD with APP mutation (Svedruzic et al., 2015).

Further, γ-secretase inhibitor may accelerate accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments in brain, if it is used as a therapeutic agent to suppress Aβ production in AD patients. Notably, the symptoms of AD worsened in a clinical trial of γ-secretase inhibitor (Doody et al., 2013).

These indicate that APP C-terminal fragment accumulation closely links to pathogenesis of sporadic and familial AD.

It was previously reported that APP or APP fragments accumulated in dystrophic neurites in AD brains (Ishii et al., 1989) and that the accumulation of APP and its metabolic fragments induced neurotoxicity and vesicular trafficking impairment (Yoshikawa et al., 1992; Kametani et al., 2004; Roy et al., 2005). It has also been reported that synaptic disorders and dendritic dysplasia occur in the absence of Aβ amyloid deposition (Boncristiano et al., 2005), and that C-terminal fragments of APP cause synaptic failure and memory impairment (Tamayev et al., 2012). Furthermore, transgenic mice expressing the C-terminal intracellular domain of APP (AICD) developed Alzheimer's-like symptoms, such as accumulation of phosphorylated tau and memory impairment (Ghosal et al., 2009). Also, accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments triggers the hydrolysis of cAMP, causing impairment of the cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway (Kametani and Haga, 2015). Moreover, APP C-terminal fragment accumulation alters the subcellular localization of APP and the distribution of Rab11, and decreases endocytosis and soma-to-axon transcytosis of LDL (Woodruff et al., 2016), and this affects axonal vesicle trafficking (Szpankowski et al., 2012; Fu and Holzbaur, 2013; Gunawardena et al., 2013). These findings support the idea that APP C-terminal fragment accumulation causes neuronal impairment.

In addition, sAPPα is involved in neurite outgrowth and has a neuroprotective effect (Baratchi et al., 2012), and AICD is involved in signal transduction (Cao and Sudhof, 2001). Thus, multiple APP domains, including the C-terminus, are required for normal nervous system function (Klevanski et al., 2015). Therefore, since APP metabolites play a variety of functions in the brain, impaired APP metabolism may have a range of effects.

Overall, these findings suggest that the trigger of AD are closely linked to impairments of APP metabolism and accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments, rather than Aβ production and Aβ amyloid formation.

The tau hypothesis

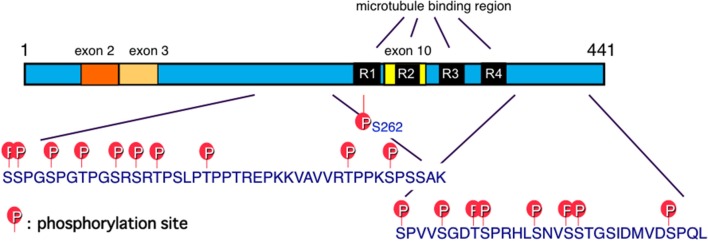

Tau is one of the microtubule-associated proteins that regulate the stability of tubulin assemblies. The human tau gene is localized in chromosome 17. Six tau isoforms are expressed in the adult human brain as a result of mRNA alternative splicing, with or without exons 2, 3, and 10 (Goedert et al., 1989a; Figure 2). Exon 10 contains the microtubule-binding region. Insertion of exon 10 affords 4-repeat (4R) tau isoforms, while 3-repeat (3R) tau isoforms are produced without exon 10 (Figure 2). Adult human brain expresses both 3R and 4R tau isoforms, which are located mainly in axons of adult neurons under normal physiological conditions. The tau hypothesis is that the principle causative substance of AD is tau.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of functional sites of tau. Six tau isoforms are expressed in the adult human brain as a result of mRNA alternative splicing, with or without exons 2, 3, and 10. Exon 10 contains the microtubule-binding region. Insertion of exon 10 affords 4-repeat (4R) tau isoforms, while 3-repeat (3R) tau isoforms are produced without exon 10 (Goedert et al., 1989a). Major tau phosphorylation sites identified in PHF-tau from AD brains are shown. Microtubule binding regions R3 and R4 form the core of tau fibrils (PHF and SF) (Taniguchi-Watanabe et al., 2016; Fitzpatrick et al., 2017).

In AD brains, 3R and 4R tau is accumulated in a hyperphosphorylated state in the pathological inclusions (Goedert, 1993; Goedert et al., 1996; Serrano-Pozo et al., 2011; Iqbal et al., 2016). Ultrastructurally, unique twisted fibrils with ~80 nm periodicity appearing as paired helical filaments (PHFs) or related straight filaments (SFs) are observed (Crowther and Wischik, 1985; Wischik et al., 1988a,b; Crowther et al., 1989; Goedert et al., 1989b; Greenberg and Davies, 1990; Lee et al., 1991). These pathological inclusions are referred to as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) if they are formed in neuronal cell bodies, while they are referred to as threads if they are formed in dendrites or axons. These findings suggested that mis-sorting of tau might induce tau pathology (Zempel and Mandelkow, 2014).

Tau pathology is staged according to Braak and Braak (Braak and Braak, 1991), and appears first in the transentorhinal region (stages I and II), then spreads to the limbic region (stages III and IV) and neocortical areas (stages V and IV). This spreading of tau pathology is strongly correlated with the extent of cognitive and clinical symptoms. Recent PET studies have shown that the spatial patterns of tau tracer binding are closely linked to the patterns of neurodegeneration and the clinical presentation in AD patients (Bejanin et al., 2017; Okamura and Yanai, 2017) and that subjective cognitive decline is indicative of early tauopathy in the medial temporal lobe, specifically in the entorhinal cortex, and to a lesser extent with elevated global levels of Aβ (Scholl et al., 2016; Schwarz et al., 2016; Buckley et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been reported that tau lesions occurred earlier than Aβ accumulation (Braak and Del Tredici, 2014; Johnson et al., 2015). Thus, progression of AD is strongly associated with tau pathology, rather than Aβ amyloid accumulation.

Tau pathologies are also seen in other neurodegenerative dementing disorders, such as frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 (FTDP-17), Pick's disease (PiD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), argyrophilic grain disease (AGD), tangle-only dementia, and chronic traumatic encephalopathies (CTE) (Iwatsubo et al., 1994; Spillantini et al., 1997, 1998; Hutton et al., 1998; Poorkaj et al., 1998; Buee and Delacourte, 1999; Goedert and Hasegawa, 1999; Lee et al., 2001; Kovacs, 2015) In particular, FTDP-17 patients exhibit many exonic and intronic mutations in the tau gene (http://www.alzforum.org/mutations), resulting in tau accumulation (Spillantini et al., 1997, 1998; Hutton et al., 1998; Poorkaj et al., 1998). These findings suggest that tau abnormalities cause accumulation of tau and degeneration of neurons. In other sporadic cases of tauopathies, including AD, the initial trigger is unclear, but wild-type tau is accumulated.

What is the tau-induced neurodegeneration? In FTDP-17, the disease causing tau-mutations cluster near the C-terminal microtubule binding repeat and impair the ability of tau to bind microtubules (Hasegawa et al., 1998), suggesting impairment of the microtubule regulation. Mis-localized tau also induces impairment of microtubule regulation (Zempel and Mandelkow, 2014). These taus form aggregation and fibril seed, and were hyperphosphorylated as described above. Furthermore, the stability of mutant and hyperphosphorylated tau increases compared to the normal tau (Yamada et al., 2015; Bardai et al., 2018). Aberrant interaction of stabilized tau with filamentous actin induces mis-stabilization of actin (Fulga et al., 2007), synaptic impairment (Cabrales Fontela et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2017; Bardai et al., 2018), and defects in mitochondrial integrity (DuBoff et al., 2012). Therefore, tau pathology causes extensive damage in the cell, such as transport system, cytoskeletal system, signaling system, and mitochondrial integrity.

Propagation of tau pathology

In an experimental model of cultured cells and mice, abnormal tau (amyloid-like fibril tau) converts normal tau to an abnormal type. Therefore, it has been hypothesized that tau aggregates form first in a small number of brain cells, from where they propagate to other regions, resulting in neurodegeneration and disease. This hypothesis has recently gained attention because it has been confirmed that tau proliferates and propagates between cells (Clavaguera et al., 2009, 2013; Nonaka et al., 2010; Hasegawa, 2016; Goedert and Spillantini, 2017). The existence of several human tauopathies with distinct fibril morphologies has led to the suggestion that different molecular conformers (or strains) of aggregated tau exist (Goedert and Spillantini, 2017). Although the transmission mechanism of tau aggregates from cell to cell is still not clear, tau pathology does spread in the brain in a well-defined manner; its distribution can be correlated with the clinical stages of disease (Braak and Braak, 1991), and it is considered that tau pathology correlates better than Aβ pathology with clinical features of dementia. Recently, we found that increase APP with or without familial AD mutations, not Aβ, may work as a receptor of abnormal tau fibrils and promote intracellular tau aggregation (Takahashi et al., 2015), suggesting that APP rather than Aβ may accelerate tau accumulation and propagation.

AD risk factors, ApoE4 and TREM2

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is one of the major apolipoproteins (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P02649). The ApoE gene has three alleles, ε2, ε3, and ε4, corresponding to isoforms E2, E3, and E4, respectively. In the central nervous system, ApoE produced and secreted by astrocytes and microglia binds to lipoprotein and is taken up into nerve cells via the ApoE receptor during the developmental stage of the central nervous system and the repair period after neuronal damage.

The ApoE4 allele is a genetic risk factor for sporadic AD (Corder et al., 1993). As the number of ε4 genes increases, the age of onset of AD declines and the incidence of AD increases (Maestre et al., 1995), and there is an increased risk of 3–4 and 8–12 times for one or two copies of the allele, respectively. It is considered that impaired apoE4 function affects the clearance pathway of Aβ (Zlokovic, 2013; Robert et al., 2017) and modulates Aβ-induced effects on inflammatory receptor signaling, including amplification of detrimental pathways and suppression of beneficial pathways (Chan et al., 2015; Tai et al., 2015). To examine the role of ApoE, human ApoE targeted replacement mice were crossed with mutant human amyloid precursor protein (APP) mice. In this context, ApoE genotypes only modulate Aβ-mediated insulin signaling impairment (Chan et al., 2015). Recently, however, P301S tau transgenic mice were generated on either a human ApoE knock-in (KI) or ApoE knockout (KO) background, and developed significant brain atrophy primarily in the hippocampus, piriform/entorhinal cortex, and amygdala, accompanied by significant lateral ventricular enlargement (Shi et al., 2017). ApoE plays an important role in regulating tau-mediated neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation, with ApoE4 causing more severe damage and the absence of ApoE being protective (Shi et al., 2017). These findings indicate that ApoE4 affects neurodegeneration independently of Aβ and Aβ amyloid in the context of tau pathology (Shi et al., 2017).

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) is expressed on the membranes of microglia and is critical for the response to injury and AD pathology (http://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9NZC2). TREM2 recognizes lipoproteins including ApoE, phospholipid and apoptotic cells and is implicated in microglial phagocytosis. Variants in the TREM2 gene increase the risk of getting AD. Initially, this was thought to be related to the elimination of Aβ plaque. TREM2 deficiency in the setting of pure tauopathy limits gliosis and neuroinflammation, as well as protecting against brain atrophy, suggesting that TREM2 facilitates a microglial response to tau pathology and/or tau-mediated damage in the brain (Bemiller et al., 2017; Leyns et al., 2017). These results are consistent with the findings of strikingly reduced inflammation and neurodegeneration in mice lacking ApoE, as described above. Therefore, the TREM2-ApoE pathway is important for facilitating the microglial response to damage in the brain, and a functional consequence of activation of the TREM2-ApoE pathway is that microglia lose the ability to regulate brain homeostasis (Krasemann et al., 2017; Ulland et al., 2017). Microglial inflammation promotes tau-dependent degeneration independently of Aβ and Aβ amyloid.

APP trigger tauopathy

APP turn over rapidly and easily metabolize (Oltersdorf et al., 1990; Weidemann et al., 2002). Therefore, impairment of APP metabolism has a serious effect on cells. Increased APP and/or its C-terminal fragments induce axonal and synaptic defects (Rusu et al., 2007; Rodrigues et al., 2012; Deyts et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2016b), thereby triggering the mis-localization of tau (Blurton-Jones and Laferla, 2006; Hochgrafe et al., 2013). This protein modulates motility in a motor-specific manner to direct intracellular transport (Chaudhary et al., 2017). Mis-localized tau proteins accumulate, form fibril seeds and propagate (He et al., 2017). The pathological tau induce further transport dysfunction (Goldsbury et al., 2006; Rusu et al., 2007), creating a vicious circle and leading to tau accumulation. Moreover, since overexpression of APP promoted the seed aggregation of intracellular tau in cultured cell, suggesting that APP may function as a receptor of abnormal tau fibrils (Takahashi et al., 2015). Thus, increased APP may accelerate pathological incorporation and propagation.

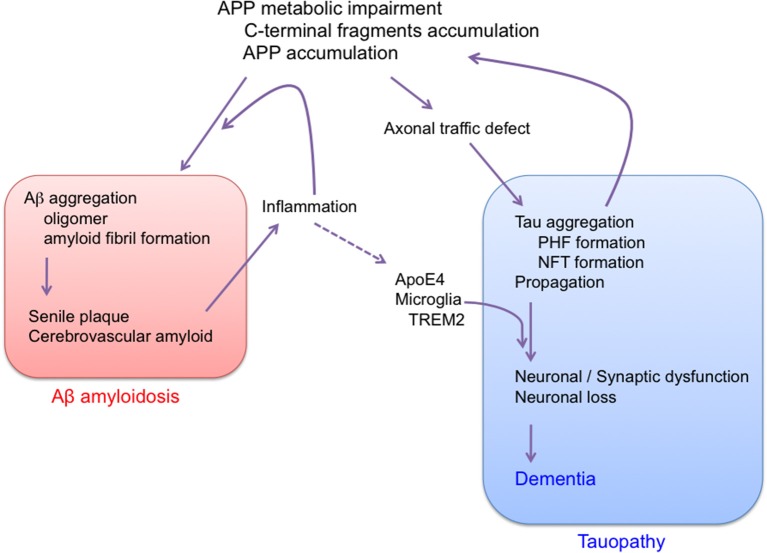

Overall, the results described above suggest that AD is a disorder that is triggered by impairment of APP metabolism, and that progresses through tau pathology (Figure 3). It is well-known that Aβ amyloidosis due to APP metabolic impairment leads to neuroinflammation, which may further affect the progression of tau pathology (Leyns and Holtzman, 2017). So far, there is no evidence that Aβ itself directly affects tau pathology. We cannot rule out the possibility that APP metabolic impairment and tau pathology might be initiated independently in sporadic AD. In any event, there is now convincing evidence that the main factor causing progression of AD is tau, not Aβ, and that Aβ amyloidosis and tau pathology should be regarded as independent pathological events. Indeed, it was recently shown that the AD risk factors ApoE4 and TREM2 are linked to tau pathology (Bemiller et al., 2017; Leyns et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2017). Moreover, the incidence of type 2 diabetes is increased in AD patients (Janson et al., 2004), and it was recently shown that tau protein is involved in the control of brain insulin signaling (Marciniak et al., 2017). Furthermore, the brains of patients with primary age-related tauopathy (PART) contain NFTs that are indistinguishable from those of AD, in the absence of Aβ amyloid plaques (Crary et al., 2014; Duyckaerts et al., 2015; Jellinger et al., 2015). Therefore, tau could contribute to the cognitive and metabolic alterations in patients with AD.

Figure 3.

Proposed sequence of major pathogenic events leading to AD. Aβ amyloidosis and tau pathology are regarded as independent pathological events. AD is APP trigger tauopathy.

The unexpected failures of all trials of AD treatment candidate drugs targeting Aβ can easily be understood if the main factor causing progression of AD is tau, not Aβ. Indeed, it has already been reported that the suppression or deletion of tau has a profound protective effect against brain damage and neurological deficits (Rapoport et al., 2002; SantaCruz et al., 2005; Roberson et al., 2007; Miao et al., 2010; Shipton et al., 2011; Bi et al., 2017). Thus, suppression of tau production currently seems to be the most promising target for development of AD therapeutic drugs.

Conclusion

The amyloid hypothesis has been the mainstream concept underlying AD research for over 20 years. However, reconsideration of APP and presenilin (PS) mutations in familial AD indicate that the trigger of AD is closely linked to impairments of APP metabolism and accumulation of APP C-terminal fragments, rather than Aβ production and Aβ amyloid formation. Furthermore, all attempts to develop Aβ-targeting drugs to treat AD have ended in failure and recent findings indicating that the main factor underlying the development and progression of AD is tau, not Aβ. Therefore, AD is a disorder that is triggered by impairment of APP metabolism, and progresses through tau pathology, not Aβ amyloid.

Author contributions

FK and MH, data collection, literature review, manuscript writing.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) JP26117005 (to MH) and JP26293084 (to FK) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, as well as a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) JP23228004 (to MH) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and a Grant-in-Aid for Research on Brain Mapping by Integrated Neurotechnologies for Disease Studies (Brain/MINDS) from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) JP14533254 (to MH).

References

- Baratchi S., Evans J., Tate W. P., Abraham W. C., Connor B. (2012). Secreted amyloid precursor proteins promote proliferation and glial differentiation of adult hippocampal neural progenitor cells. Hippocampus 22, 1517–1527. 10.1002/hipo.20988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardai F. H., Wang L., Mutreja Y., Yenjerla M., Gamblin T. C., Feany M. B. (2018). A conserved cytoskeletal signaling cascade mediates neurotoxicity of FTDP-17 tau mutations in vivo. J. Neurosci. 38, 108–119. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1550-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejanin A., Schonhaut D. R., La Joie R., Kramer J. H., Baker S. L., Sosa N., et al. (2017). Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Brain 140, 3286–3300. 10.1093/brain/awx243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemiller S. M., McCray T. J., Allan K., Formica S. V., Xu G., Wilson G., et al. (2017). TREM2 deficiency exacerbates tau pathology through dysregulated kinase signaling in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 12:74. 10.1186/s13024-017-0216-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentahir M., Nyabi O., Verhamme J., Tolia A., Horré K., Wiltfang J., et al. (2006). Presenilin clinical mutations can affect gamma-secretase activity by different mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 96, 732–742. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi M., Gladbach A., Van Eersel J., Ittner A., Przybyla M., Van Hummel A., et al. (2017). Tau exacerbates excitotoxic brain damage in an animal model of stroke. Nat. Commun. 8, 473. 10.1038/s41467-017-00618-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boncristiano S., Calhoun M. E., Howard V., Bondolfi L., Kaeser S. A., Wiederhold K. H., et al. (2005). Neocortical synaptic bouton number is maintained despite robust amyloid deposition in APP23 transgenic mice. Neurobiol. Aging 26, 607–613. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blurton-Jones M., Laferla F. M. (2006). Pathways by which Abeta facilitates tau pathology. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 3, 437–448. 10.2174/156720506779025242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Braak E. (1991). Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259. 10.1007/BF00308809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Del Tredici K. (2014). Are cases with tau pathology occurring in the absence of Abeta deposits part of the AD-related pathological process? Acta Neuropathol. 128, 767–772. 10.1007/s00401-014-1356-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brion J. P., Passareiro H., Nunez J., Flament-Durand J. (1985). Mise en évidence immunologique de la protéine tau au niveau deslésions de dégénérescence neurofibrillaire de la maladie d'Alzheimer. Arch. Biol. 95, 229–235. [Google Scholar]

- Bryan K. J., Lee H., Perry G., Smith M. A., Casadesus G. (2009). Transgenic Mouse Models of Alzheimer's Disease: Behavioral Testing and Considerations Methods of Behavior Analysis in Neuroscience. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley R. F., Hanseeuw B., Schultz A. P., Vannini P., Aghjayan S. L., Properzi M. J., et al. (2017). Region-specific association of subjective cognitive decline with tauopathy independent of global beta-amyloid burden. JAMA Neurol. 74, 1455–1463. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buée L., Delacourte A. (1999). Comparative biochemistry of tau in progressive supranuclear palsy, corticobasal degeneration, FTDP-17 and Pick's disease. Brain Pathol. 9, 681–693. 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00550.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum J. D., Liu K. N., Luo Y., Slack J. L., Stocking K. L., Peschon J. J., et al. (1998). Evidence that tumor necrosis factor alpha converting enzyme is involved in regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of the Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27765–27767. 10.1074/jbc.273.43.27765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrales Fontela Y., Kadavath H., Biernat J., Riedel D., Mandelkow E., Zweckstetter M. (2017). Multivalent cross-linking of actin filaments and microtubules through the microtubule-associated protein Tau. Nat. Commun. 8, 1981. 10.1038/s41467-017-02230-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X., Südhof T. C. (2001). A transcriptionally active complex of APP with Fe65 and histone acetyltransferase Tip60. Science 293, 115–120. 10.1126/science.1058783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell A., Grünberg J., Pesold B., Diehlmann A., Citron M., Nixon R., et al. (1998). The proteolytic fragments of the Alzheimer's disease-associated presenilin-1 form heterodimers and occur as a 100-150-kDa molecular mass complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3205–3211. 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E. S., Chen C., Cole G. M., Wong B. S. (2015). Differential interaction of Apolipoprotein-E isoforms with insulin receptors modulates brain insulin signaling in mutant human amyloid precursor protein transgenic mice. Sci. Rep. 5:13842. 10.1038/srep13842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary A. R., Berger F., Berger C. L., Hendricks A. G. (2017). Tau directs intracellular trafficking by regulating the forces exerted by kinesin and dynein teams. Traffic. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/tra.12537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Gu Y., Hasegawa H., Ruan X., Arawaka S., Fraser P., et al. (2002). Presenilin 1 mutations activate gamma 42-secretase but reciprocally inhibit epsilon -secretase cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) and S3-Cleavage of Notch. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36521–36526. 10.1074/jbc.M205093200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chételat G. (2013). Alzheimer disease: Abeta-independent processes-rethinking preclinical AD. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 123–124. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chételat G., La Joie R., Villain N., Perrotin A., De La Sayette V., Eustache F., et al. (2013). Amyloid imaging in cognitively normal individuals, at-risk populations and preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage Clin. 2, 356–365. 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavaguera F., Akatsu H., Fraser G., Crowther R. A., Frank S., Hench J., et al. (2013). Brain homogenates from human tauopathies induce tau inclusions in mouse brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 9535–9540. 10.1073/pnas.1301175110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clavaguera F., Bolmont T., Crowther R. A., Abramowski D., Frank S., Probst A., et al. (2009). Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 909–913. 10.1038/ncb1901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corder E. H., Saunders A. M., Strittmatter W. J., Schmechel D. E., Gaskell P. C., Small G. W., et al. (1993). Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer's disease in late onset families. Science 261, 921–923. 10.1126/science.8346443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crary J. F., Trojanowski J. Q., Schneider J. A., Abisambra J. F., Abner E. L., Alafuzoff I., et al. (2014). Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 755–766. 10.1007/s00401-014-1349-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther R. A., Wischik C. M. (1985). Image reconstruction of the Alzheimer paired helical filament. EMBO J. 4, 3661–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowther T., Goedert M., Wischik C. M. (1989). The repeat region of microtubule-associated protein tau forms part of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Med. 21, 127–132. 10.3109/07853898909149199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupers P., Orlans I., Craessaerts K., Annaert W., De Strooper B. (2001). The amyloid precursor protein (APP)-cytoplasmic fragment generated by gamma-secretase is rapidly degraded but distributes partially in a nuclear fraction of neurones in culture. J. Neurochem. 78, 1168–1178. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00516.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies C. A., Mann D. M., Sumpter P. Q., Yates P. O. (1987). A quantitative morphometric analysis of the neuronal and synaptic content of the frontal and temporal cortex in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 78, 151–164. 10.1016/0022-510X(87)90057-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis D. G., Schmitt F. A., Wekstein D. R., Markesbery W. R. (1999). Alzheimer neuropathologic alterations in aged cognitively normal subjects. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 58, 376–388. 10.1097/00005072-199904000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Strooper B., Saftig P., Craessaerts K., Vanderstichele H., Guhde G., Annaert W., et al. (1998). Deficiency of presenilin-1 inhibits the normal cleavage of amyloid precursor protein. Nature 391, 387–390. 10.1038/34910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delabar J. M., Goldgaber D., Lamour Y., Nicole A., Huret J. L., De Grouchy J., et al. (1987). Beta amyloid gene duplication in Alzheimer's disease and karyotypically normal Down syndrome. Science 235, 1390–1392. 10.1126/science.2950593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyts C., Clutter M., Herrera S., Jovanovic N., Goddi A., Parent A. T. (2016). Loss of presenilin function is associated with a selective gain of APP function. Elife 5:e15645. 10.7554/eLife.15645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody R. S., Raman R., Farlow M., Iwatsubo T., Vellas B., Joffe S., et al. (2013). A phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 369, 341–350. 10.1056/NEJMoa1210951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody R. S., Thomas R. G., Farlow M., Iwatsubo T., Vellas B., Joffe S., et al. (2014). Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 311–321. 10.1056/NEJMoa1312889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBoff B., Götz J., Feany M. B. (2012). Tau promotes neurodegeneration via DRP1 mislocalization in vivo. Neuron 75, 618–632. 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyckaerts C., Braak H., Brion J.-P., Buée L., Del Tredici K., Goedert M., et al. (2015). PART is part of Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 749–756. 10.1007/s00401-015-1390-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edison P., Archer H. A., Hinz R., Hammers A., Pavese N., Tai Y. F., et al. (2007). Amyloid, hypometabolism, and cognition in Alzheimer disease: An [11C]PIB and [18F]FDG PET study. Neurology 68, 501–508. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000244749.20056.d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan A. M., Mintun M. A., Shah A. R., Aldea P., Roe C. M., Mach R. H., et al. (2009). Cerebrospinal fluid tau and ptau(181) increase with cortical amyloid deposition in cognitively normal individuals: implications for future clinical trials of Alzheimer's disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 1, 371–380. 10.1002/emmm.200900048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick A. W. P., Falcon B., He S., Murzin A. G., Murshudov G., Garringer H. J., et al. (2017). Cryo-EM structures of tau filaments from Alzheimer's disease. Nature 547, 185–190. 10.1038/nature23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., McGrath G., Zhang J., Ruddy D. A., Sym M., Apfeld J., et al. (2002). aph-1 and pen-2 are required for Notch pathway signaling, gamma-secretase cleavage of betaAPP, and presenilin protein accumulation. Dev. Cell 3, 85–97. 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00189-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M. M., Holzbaur E. L. (2013). JIP1 regulates the directionality of APP axonal transport by coordinating kinesin and dynein motors. J. Cell Biol. 202, 495–508. 10.1083/jcb.201302078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulga T. A., Elson-Schwab I., Khurana V., Steinhilb M. L., Spires T. L., Hyman B. T., et al. (2007). Abnormal bundling and accumulation of F-actin mediates tau-induced neuronal degeneration in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 139–148. 10.1038/ncb1528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal K., Vogt D. L., Liang M., Shen Y., Lamb B. T., Pimplikar S. W. (2009). Alzheimer's disease-like pathological features in transgenic mice expressing the APP intracellular domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18367–18372. 10.1073/pnas.0907652106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobini E., Gold G. (2013). Alzheimer disease therapy[mdash]moving from amyloid-[beta] to tau. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 9, 677–686. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenner G. G., Wong C. W. (1984). Alzheimer's disease: INITIAL report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 120, 885–890. 10.1016/S0006-291X(84)80190-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M. (1993). Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Neurosci. 16, 460–465. 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90078-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Hasegawa M. (1999). The tauopathies: toward an experimental animal model. Am. J. Pathol. 154, 1–6. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65242-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Spillantini M. G. (2017). Propagation of Tau aggregates. Mol. Brain 10, 18. 10.1186/s13041-017-0298-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Hasegawa M., Jakes R., Crowther R. A., Klug A. (1996). Molecular dissection of the neurofibrillary lesions of Alzheimer's disease. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 61, 565–573. 10.1101/SQB.1996.061.01.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Jakes R., Rutherford D., Crowther R. A. (1989a). Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 3, 519–526. 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90210-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Spillantini M. G., Potier M. C., Ulrich J., Crowther R. A. (1989b). Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding an isoform of microtubule-associated protein tau containing four tandem repeats: differential expression of tau protein mRNAs in human brain. EMBO J. 8, 393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedert M., Wischik C. M., Crowther R. A., Walker J. E., Klug A. (1988). Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 4051–4055. 10.1073/pnas.85.11.4051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsbury C., Mocanu M. M., Thies E., Kaether C., Haass C., Keller P., et al. (2006). Inhibition of APP trafficking by tau protein does not increase the generation of amyloid-beta peptidesPresenilin/gamma-secretase activity regulates protein clearance from the endocytic recycling compartment Presenilin-1-mediated retention of APP derivatives in early biosynthetic compartments A partial failure of membrane protein turnover may cause Alzheimer's disease: a new hypothesis. Traffic 7, 873–888. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutte C., Tsunozaki M., Hale V. A., Priess J. R. (2002). APH-1 is a multipass membrane protein essential for the Notch signaling pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 775–779. 10.1073/pnas.022523499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg S. G., Davies P. (1990). A preparation of Alzheimer paired helical filaments that displays distinct tau proteins by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 5827–5831. 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundke-Iqbal I., Iqbal K., Tung Y. C., Quinlan M., Wisniewski H. M., Binder L. I. (1986). Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 4913–4917. 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunawardena S., Yang G., Goldstein L. S. (2013). Presenilin controls kinesin-1 and dynein function during APP-vesicle transport in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 3828–3843. 10.1093/hmg/ddt237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J., Allsop D. (1991). Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12, 383–388. 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90609-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002). The Amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's Disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 297, 353–356. 10.1126/science.1072994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J. A., Higgins G. A. (1992). Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science 256, 184–185. 10.1126/science.1566067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M. (2016). Molecular mechanisms in the pathogenesis of alzheimer's disease and tauopathies-prion-like seeded aggregation and phosphorylation. Biomolecules 6:e24. 10.3390/biom6020024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M., Smith M. J., Goedert M. (1998). Tau proteins with FTDP-17 mutations have a reduced ability to promote microtubule assembly. FEBS Lett. 437, 207–210. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)01217-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z., Guo J. L., McBride J. D., Narasimhan S., Kim H., Changolkar L., et al. (2017). Amyloid-beta plaques enhance Alzheimer's brain tau-seeded pathologies by facilitating neuritic plaque tau aggregation. Nat. Med. 24, 29–38. 10.1038/nm.4443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochgräfe K., Sydow A., Mandelkow E. M. (2013). Regulatable transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer disease: onset, reversibility and spreading of Tau pathology. FEBS J. 280, 4371–4381. 10.1111/febs.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton M., Lendon C. L., Rizzu P., Baker M., Froelich S., Houlden H., et al. (1998). Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature 393, 702–705. 10.1038/31508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C. X. (2016). Tau and neurodegenerative disease: the story so far. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 15–27. 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T., Kametani F., Haga S., Sato M. (1989). The immunohistochemical demonstration of subsequences of the precursor of the amyloid A4 protein in senile plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 15, 135–147. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1989.tb01216.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwatsubo T., Hasegawa M., Ihara Y. (1994). Neuronal and glial tau-positive inclusions in diverse neurologic diseases share common phosphorylation characteristics. Acta Neuropathol. 88, 129–136. 10.1007/BF00294505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson J., Laedtke T., Parisi J. E., O'Brien P., Petersen R. C., Butler P. C. (2004). Increased risk of type 2 diabetes in Alzheimer disease. Diabetes 53, 474–481. 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jellinger K. A., Alafuzoff I., Attems J., Beach T. G., Cairns N. J., Crary J. F., et al. (2015). PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 757–762. 10.1007/s00401-015-1407-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. A., Schultz A., Betensky R. A., Becker J. A., Sepulcre J., Rentz D., et al. (2015). Tau PET imaging in aging and early Alzheimer's disease. Ann. Neurol. 79, 110–119. 10.1002/ana.24546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametani F. (2008). epsilon-Secretase: reduction of amyloid precursor protein epsilon-site cleavage in Alzheimer's disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5, 165–171. 10.2174/156720508783954776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametani F., Haga S. (2015). Accumulation of carboxy-terminal fragments of APP increases phosphodiesterase 8B. Neurobiol. Aging 36, 634–637. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kametani F., Usami M., Tanaka K., Kume H., Mori H. (2004). Mutant presenilin (A260V) affects Rab8 in PC12D cell. Neurochem. Int. 44, 313–320. 10.1016/S0197-0186(03)00176-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J., Lemaire H. G., Unterbeck A., Salbaum J. M., Masters C. L., Grzeschik K. H., et al. (1987). The precursor of Alzheimer's disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature 325, 733–736. 10.1038/325733a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Chakrabarty P., Hanna A., March A., Dickson D. W., Borchelt D. R., et al. (2013). Normal cognition in transgenic BRI2-Abeta mice. Mol. Neurodegener. 8, 15. 10.1186/1750-1326-8-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Onstead L., Randle S., Price R., Smithson L., Zwizinski C., et al. (2007). Abeta40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J. Neurosci. 27, 627–633. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4849-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevanski M., Herrmann U., Weyer S. W., Fol R., Cartier N., Wolfer D. P., et al. (2015). The APP intracellular domain is required for normal synaptic morphology, synaptic plasticity, and hippocampus-dependent behavior. J. Neurosci. 35, 16018–16033. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2009-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolata G. (1985). Down syndrome–Alzheimer's linked. Science 230, 1152–1153. 10.1126/science.2933807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo J., Honda T., Mori H., Hamada Y., Miura R., Ogawara M., et al. (1988). The carboxyl third of tau is tightly bound to paired helical filaments. Neuron 1, 827–834. 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90130-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R., Ilagan M. X. (2004). Gamma-secretase: proteasome of the membrane? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 499–504. 10.1038/nrm1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosik K. S., Orecchio L. D., Binder L., Trojanowski J. Q., Lee V. M., Lee G. (1988). Epitopes that span the tau molecule are shared with paired helical filaments. Neuron 1, 817–825. 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90129-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs G. G. (2015). Invited review: neuropathology of tauopathies: principles and practice. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 41, 3–23. 10.1111/nan.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasemann S., Madore C., Cialic R., Baufeld C., Calcagno N., El Fatimy R., et al. (2017). The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581.e569. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammich S., Kojro E., Postina R., Gilbert S., Pfeiffer R., Jasionowski M., et al. (1999). Constitutive and regulated alpha-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by a disintegrin metalloprotease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 3922–3927. 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V. M., Balin B. J., Otvos L., Jr., Trojanowski J. Q. (1991). A68: a major subunit of paired helical filaments and derivatized forms of normal Tau. Science 251, 675–678. 10.1126/science.1899488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V. M., Goedert M., Trojanowski J. Q. (2001). Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1121–1159. 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyns C. E. G., Holtzman D. M. (2017). Glial contributions to neurodegeneration in tauopathies. Mol. Neurodegener. 12, 50. 10.1186/s13024-017-0192-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyns C. E. G., Ulrich J. D., Finn M. B., Stewart F. R., Koscal L. J., Remolina Serrano J., et al. (2017). TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 11524–11529. 10.1073/pnas.1710311114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Rinne J. O., Mosconi L., Pirraglia E., Rusinek H., Desanti S., et al. (2008). Regional analysis of FDG and PIB-PET images in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Eur. J. Nuclear Med. Mol. Image 35, 2169–2181. 10.1007/s00259-008-0833-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestre G., Ottman R., Stern Y., Gurland B., Chun M., Tang M. X., et al. (1995). Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer's disease: ethnic variation in genotypic risks. Ann. Neurol. 37, 254–259. 10.1002/ana.410370217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak E., Leboucher A., Caron E., Ahmed T., Tailleux A., Dumont J., et al. (2017). Tau deletion promotes brain insulin resistance. J. Exp. Med. 214, 2257–2269. 10.1084/jem.20161731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E., Mallory M., Alford M., DeTeresa R., Hansen L. A., Mckeel D. W., Jr., et al. (2001). Altered expression of synaptic proteins occurs early during progression of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 56, 127–129. 10.1212/WNL.56.1.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masters C. L., Simms G., Weinman N. A., Multhaup G., McDonald B. L., Beyreuther K. (1985). Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 4245–4249. 10.1073/pnas.82.12.4245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao Y., Chen J., Zhang Q., Sun A. (2010). Deletion of tau attenuates heat shock-induced injury in cultured cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 88, 102–110. 10.1002/jnr.22188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka T., Watanabe S. T., Iwatsubo T., Hasegawa M. (2010). Seeded aggregation and toxicity of {alpha}-synuclein and tau: cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34885–34898. 10.1074/jbc.M110.148460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nukina N., Ihara Y. (1986). One of the antigenic determinants of paired helical filaments is related to tau protein. J. Biochem. 99, 1541–1544. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura N., Yanai K. (2017). Brain imaging: applications of tau PET imaging. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 13, 197–198. 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltersdorf T., Ward P. J., Henriksson T., Beattie E. C., Neve R., Lieberburg I., et al. (1990). The Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Identification of a stable intermediate in the biosynthetic/degradative pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 4492–4497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowitzki S., Deptula D., Thurfjell L., Barkhof F., Bohrmann B., Brooks D. J., et al. (2012). Mechanism of amyloid removal in patients with Alzheimer disease treated with gantenerumab. Arch. Neurol. 69, 198–207. 10.1001/archneurol.2011.1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera M., Alcolea D., Sánchez-Valle R., Guardia-Laguarta C., Colom-Cadena M., Badiola N., et al. (2013). Distinct patterns of APP processing in the CNS in autosomal-dominant and sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 125, 201–213. 10.1007/s00401-012-1062-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorkaj P., Bird T. D., Wijsman E., Nemens E., Garruto R. M., Anderson L., et al. (1998). Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 43, 815–825. 10.1002/ana.410430617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. L., Mckeel D. W., Jr., Buckles V. D., Roe C. M., Xiong C., Grundman M., et al. (2009). Neuropathology of nondemented aging: presumptive evidence for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 30, 1026–1036. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport M., Dawson H. N., Binder L. I., Vitek M. P., Ferreira A. (2002). Tau is essential to β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 6364–6369. 10.1073/pnas.092136199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robakis N. K., Georgakopoulos A. (2014). Allelic interference: a mechanism for trans-dominant transmission of loss of function in the neurodegeneration of Familial Alzheimer's Disease. Neurodegener. Dis. 13, 126–130. 10.1159/000354241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberson E. D., Scearce-Levie K., Palop J. J., Yan F., Cheng I. H., Wu T., et al. (2007). Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates Amyloid ß-Induced Deficits in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Science 316, 750–754. 10.1126/science.1141736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert J., Button E. B., Yuen B., Gilmour M., Kang K., Bahrabadi A., et al. (2017). Clearance of beta-amyloid is facilitated by apolipoprotein E and circulating high-density lipoproteins in bioengineered human vessels. Elife 6:e29595. 10.7554/eLife.29595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues E. M., Weissmiller A. M., Goldstein L. S. (2012). Enhanced beta-secretase processing alters APP axonal transport and leads to axonal defects. Hum. Mol. Genet. 21, 4587–4601. 10.1093/hmg/dds297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovelet-Lecrux A., Hannequin D., Raux G., Meur N. L., Laquerrière A., Vital A., et al. (2006). APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat. Genet. 38, 24–26. 10.1038/ng1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy S., Zhang B., Lee V. M.-Y., Trojanowski J. Q. (2005). Axonal transport defects: a common theme in neurodegenerative diseases. Acta Neuropathol. 109, 5–13. 10.1007/s00401-004-0952-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusu P., Jansen A., Soba P., Kirsch J., Löwer A., Merdes G., et al. (2007). Axonal accumulation of synaptic markers in APP transgenic Drosophila depends on the NPTY motif and is paralleled by defects in synaptic plasticity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 1079–1086. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05341.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloway S., Sperling R., Fox N. C., Blennow K., Klunk W., Raskind M., et al. (2014). Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 322–333. 10.1056/NEJMoa1304839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SantaCruz K., Lewis J., Spires T., Paulson J., Kotilinek L., Ingelsson M., et al. (2005). Tau suppression in a neurodegenerative mouse model improves memory function. Science 309, 476–481. 10.1126/science.1113694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöll M., Lockhart S. N., Schonhaut D. R., O'neil J. P., Janabi M., Ossenkoppele R., et al. (2016). PET imaging of tau deposition in the aging human brain. Neuron 89, 971–982. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz A. J., Yu P., Miller B. B., Shcherbinin S., Dickson J., Navitsky M., et al. (2016). Regional profiles of the candidate tau PET ligand 18F-AV-1451 recapitulate key features of Braak histopathological stages. Brain 139, 1539–1550. 10.1093/brain/aww023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe D. J. (1991). The molecular pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 6, 487–498. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Pozo A., Frosch M. P., Masliah E., Hyman B. T. (2011). Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 1, a006189. 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankar G. M., Li S., Mehta T. H., Garcia-Munoz A., Shepardson N. E., Smith I., et al. (2008). Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer's brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat. Med. 14, 837–842. 10.1038/nm1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Kelleher R. J., III (2007). The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 403–409. 10.1073/pnas.0608332104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Yamada K., Liddelow S. A., Smith S. T., Zhao L., Luo W., et al. (2017). ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549, 523–527. 10.1038/nature24016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipton O. A., Leitz J. R., Dworzak J., Acton C. E. J., Tunbridge E. M., Denk F., et al. (2011). Tau Protein Is Required for Amyloid β-induced impairment of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 31, 1688–1692. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2610-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M. G., Goedert M., Crowther R. A., Murrell J. R., Farlow M. R., Ghetti B. (1997). Familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia: a disease with abundant neuronal and glial tau filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4113–4118. 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M. G., Murrell J. R., Goedert M., Farlow M. R., Klug A., Ghetti B. (1998). Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95, 7737–7741. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SvedruŽić Ž. M., Popović K., Šendula-Jengić V. (2015). Decrease in catalytic capacity of gamma-secretase can facilitate pathogenesis in sporadic and Familial Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 67, 55–65. 10.1016/j.mcn.2015.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szpankowski L., Encalada S. E., Goldstein L. S. (2012). Subpixel colocalization reveals amyloid precursor protein-dependent kinesin-1 and dynein association with axonal vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 8582–8587. 10.1073/pnas.1120510109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai L. M., Ghura S., Koster K. P., Liakaite V., Maienschein-Cline M., Kanabar P., et al. (2015). APOE-modulated Aβ-induced neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease: current landscape, novel data, and future perspective. J. Neurochem. 133, 465–488. 10.1111/jnc.13072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M., Miyata H., Kametani F., Nonaka T., Akiyama H., Hisanaga S.-I., et al. (2015). Extracellular association of APP and tau fibrils induces intracellular aggregate formation of tau. Acta Neuropathol. 129, 895–907. 10.1007/s00401-015-1415-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi N., Tomita T., Hayashi I., Tsuruoka M., Niimura M., Takahashi Y., et al. (2003). The role of presenilin cofactors in the gamma-secretase complex. Nature 422, 438–441. 10.1038/nature01506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamayev R., Matsuda S., Arancio O., D'adamio L. (2012). beta- but not gamma-secretase proteolysis of APP causes synaptic and memory deficits in a mouse model of dementia. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 171–179. 10.1002/emmm.201100195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi-Watanabe S., Arai T., Kametani F., Nonaka T., Masuda-Suzukake M., Tarutani A., et al. (2016). Biochemical classification of tauopathies by immunoblot, protein sequence and mass spectrometric analyses of sarkosyl-insoluble and trypsin-resistant tau. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 267–280. 10.1007/s00401-015-1503-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesco G., Ginestroni A., Hiltunen M., Kim M., Dolios G., Hyman B. T., et al. (2005). APP substitutions V715F and L720P alter PS1 conformation and differentially affect Abeta and AICD generation. J. Neurochem. 95, 446–456. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03381.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulland T. K., Song W. M., Huang S. C.-C., Ulrich J. D., Sergushichev A., Beatty W. L., et al. (2017). TREM2 maintains microglial metabolic fitness in Alzheimer's Disease. Cell 170, 649–663.e613. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassar R., Bennett B. D., Babu-Khan S., Kahn S., Mendiaz E. A., Denis P., et al. (1999). Beta-secretase cleavage of Alzheimer's amyloid precursor protein by the transmembrane aspartic protease BACE. Science 286, 735–741. 10.1126/science.286.5440.735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker E. S., Martinez M., Brunkan A. L., Goate A. (2005). Presenilin 2 familial Alzheimer's disease mutations result in partial loss of function and dramatic changes in Abeta 42/40 ratios. J. Neurochem. 92, 294–301. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02858.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidemann A., Eggert S., Reinhard F. B., Vogel M., Paliga K., Baier G., et al. (2002). A novel epsilon-cleavage within the transmembrane domain of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein demonstrates homology with Notch processing. Biochemistry 41, 2825–2835. 10.1021/bi015794o [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley J. C., Hudson M., Kanning K. C., Schecterson L. C., Bothwell M. (2005). Familial Alzheimer's disease mutations inhibit gamma-secretase-mediated liberation of beta-amyloid precursor protein carboxy-terminal fragment. J. Neurochem. 94, 1189–1201. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- William C. M., Andermann M. L., Goldey G. J., Roumis D. K., Reid R. C., Shatz C. J., et al. (2012). Synaptic plasticity defect following visual deprivation in Alzheimer's disease model transgenic mice. J. Neurosci. 32, 8004–8011. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5369-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischik C. M., Novak M., Edwards P. C., Klug A., Tichelaar W., Crowther R. A. (1988a). Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 4884–4888. 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wischik C. M., Novak M., Thøgersen H. C., Edwards P. C., Runswick M. J., Jakes R., et al. (1988b). Isolation of a fragment of tau derived from the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 4506–4510. 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff G., Reyna S. M., Dunlap M., Van Der Kant R., Callender J. A., Young J. E., et al. (2016). Defective transcytosis of APP and lipoproteins in human iPSC-derived neurons with familial Alzheimer's disease mutations. Cell Rep. 17, 759–773. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia D., Watanabe H., Wu B., Lee S. H., Li Y., Tsvetkov E., et al. (2015). Presenilin-1 knockin mice reveal loss-of-function mechanism for familial Alzheimer's disease. Neuron 85, 967–981. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. H., Yan Y., Kang Y., Jiang Y., Melcher K., Xu H. E. (2016a). Alzheimer's disease-associated mutations increase amyloid precursor protein resistance to gamma-secretase cleavage and the Abeta42/Abeta40 ratio. Cell Discov. 2:16026. 10.1038/celldisc.2016.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W., Weissmiller A. M., White J. A., II., Fang F., Wang X., Wu Y., et al. (2016b). Amyloid precursor protein-mediated endocytic pathway disruption induces axonal dysfunction and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1815–1833. 10.1172/JCI82409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Patel T. K., Hochgräfe K., Mahan T. E., Jiang H., Stewart F. R., et al. (2015). Analysis of in vivo turnover of tau in a mousemodel of tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener. 10, 55 10.1186/s13024-015-0052-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa K., Aizawa T., Hayashi Y. (1992). Degeneration in vitro of post-mitotic neurons overexpressing the Alzheimer amyloid protein precursor. Nature 359, 64–67. 10.1038/359064a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G., Nishimura M., Arawaka S., Levitan D., Zhang L., Tandon A., et al. (2000). Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and betaAPP processing. Nature 407, 48–54. 10.1038/35024009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zempel H., Mandelkow E. (2014). Lost after translation: missorting of Tau protein and consequences for Alzheimer disease. Trends Neurosci. 37, 721–732. 10.1016/j.tins.2014.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., McInnes J., Wierda K., Holt M., Herrmann A. G., Jackson R. J., et al. (2017). Tau association with synaptic vesicles causes presynaptic dysfunction. Nat. Commun. 8:15295. 10.1038/ncomms15295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic B. V. (2013). Cerebrovascular effects of apolipoprotein e: implications for alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 70, 440–444. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.2152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]