To the Editor

As more people in the United States age with chronic disease,1 needs for caregiving also increase.2 Whether the source of caregiving for disabled older adults is changing is unknown. This study examined temporal trends in caregiving for home-dwelling older adults with functional disability.

Methods

This study used data from the nationally representative US Health and Retirement Study (HRS),3 a longitudinal panel survey of a multistage probability sample of households with adults aged 51 years and older with follow up every 2 years and new panels enrolled every 6 years. Interviews were in-person or by telephone; the initial response rates were 79% and follow-up rates 85%–91%. For this study, home-dwelling adults aged 55 and older with 1 or more impairments in basic or instrumental activities of daily living (ADL/IADLs) surveyed between 1998 and 2012 were included. Primary outcome was caregiving source for unpaid or paid assistance with impairments. Logistic regression was used to measure temporal trends in demographics, comorbidities, and caregiver type with study wave as the primary independent variable. Trends in caregiver types were compared by demographic subsets. All models adjusted for survey weighting and design (see Table for list of variables) as well as respondent repeated measures. This study was determined by the University of Michigan institutional review board to be exempt from review. All participants provided informed consent (oral). Analysis was performed using Stata 14.0; 2-sided P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

There were 5,198 individuals and 39,060 observations of home-dwelling older adults with 1 or more impairments; mean (SD) age, 72.8 (10.5), 54.3% female, 77.3% white, net worth $341,490 ($9,865); 68.0% high school graduates; and with 2.70 (0.02) impairments. From 1998 to 2012, the cohort had significantly more women (52.4% to 53.7%), fewer whites (85.4% to 78.9%), greater net worth ($262,917 to $350,676), more high school graduates (59.6% to 75.0%), more ADL/IADL impairments (2.74 to 2.85), and higher rates of multiple self-reported medical conditions.

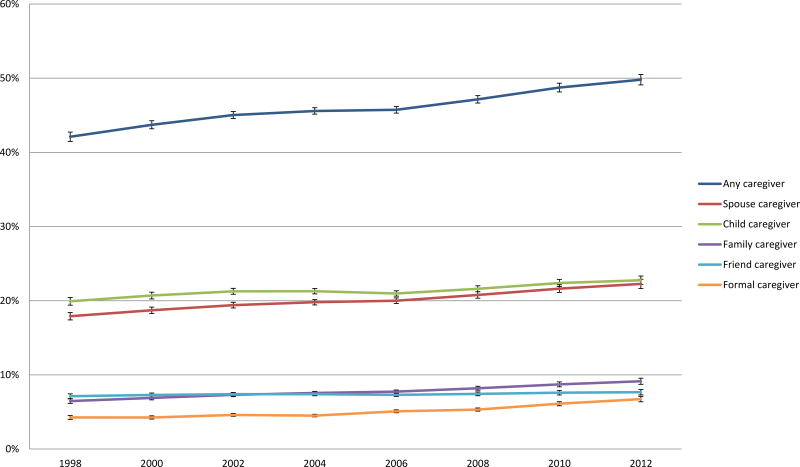

Individuals increasingly reported caregiver help, from 45.1% (95% CI 43.6%–46.6%) in 1998 to 51.4% (49.6%–53.2%) in 2012 (p <0.001) (Figure). Assistance was increasingly provided by spouses (odds ratio [OR], 1.05, 95% CI 1.03–1.06), children (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.02–1.05), other family (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.04–1.09) and paid caregivers (OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.07–1.13) over each 2-year period (Table). Within subgroups, the increase in caregiving with every biennial survey wave was greater for those with fewer ADL/IADL impairments (p-trend=0.03) and men (p-trend<0.001). In addition, increases in paid caregiving were greater for those with net worth above the mean (p-trend=0.01) and a high school diploma (p-trend=0.003).

Figure 1. Adjusted frequency of caregiver assistance by source over time from 1998–2012 in home-bound functionally disabled people age 55+.

Model adjusted for: whether interview was completed with a proxy, the survey weighting, sample design, and clustering from repeated respondent measures. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval around each point estimate.

Table 1.

Weighted percentage of caregiver assistance and temporal trends (OR for two year increases with 95% confidence intervals) from 1998–2012 in home-dwelling, functionally disabled individuals over age 55 (N=39,060f).

| Any caregiver N=18,704f |

Spouse as caregiver N=7,965f |

Child as caregiver N=9,168f |

Family as caregiver N=3,257f |

Friend as caregiver N=2,891f |

Paid caregiving N=2,024f |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| % (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

% (95% CI) |

ORd (95% CI) |

|

| Entire population: | ||||||||||||

| Minimally adjusteda | 46.2 (45.4–47.1) | 1.06c (1.05–1.07) | 20.2 (19.5–20.9) | 1.05 (1.03–1.06) | 21.4 (20.8–22.1) | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | 7.8 (7.4–8.3) | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | 7.4 (7.0–7.8) | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) | 5.2 (4.9–5.5) | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Fully adjustedb | 1.07 (1.05–1.08) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 1.03 (1.02–1.05) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 0.98 (0.96–1.01) | 1.08 (1.05–1.12) | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| R2 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.21 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Demographic subgroups:b | ||||||||||||

| No. of Disabilities: | ||||||||||||

| 1–2 | 26.0 (25.2–26.7) | 1.08 (1.06–1.10) | 12.2 (11.6–12.8) | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | 10.4 (09.9–10.4) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | 3.5 (3.1–3.8) | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | 2.9 (2.6–3.2) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 1.3 (1.1–1.5) | 1.13 (1.05–1.21) |

| 3–4 | 71.6 (70.1–72.9) | 1.05 (1.01–1.08) | 32.9 (31.3–34.5) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 31.6 (30.1–33.1) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 12.0 (10.9–13.1) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 10.6 (9.7–11.6) | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 6.3 (5.6–7.0) | 1.08 (1.01–1.16) |

| >4 | 92.7 (91.6–93.6) | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 36.1 (34.2–38.0) | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 50.4 (48.6–52.3) | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) | 19.5 (18.2–20.9) | 1.04 (1.00–1.08) | 20.3 (19.0–21.7) | 0.96 (0.93–1.00) | 17.7 (16.6–19.0) | 1.07 (1.03–1.11) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| P(trend) | 0.03 | <0.001 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.05 | 0.26 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Sex: | ||||||||||||

| Women | 54.2 (53.1–55.3) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 16.5 (15.6–17.5) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 31.3 (30.1–32.2) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 10.7 (10.1–11.4) | 1.03 (1.00–1.06) | 9.7 (9.1–10.3) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 7.0 (6.6–7.6) | 1.08 (1.04–1.12) |

| Men | 37.2 (36.0–38.4) | 1.09 (1.07–1.12) | 24.3 (23.2–25.4) | 1.07 (1.05–1.10) | 10.6 (9.9–11.3) | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | 4.6 (4.1–5.1) | 1.10 (1.04–1.16) | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 1.01 (0.96–1.06) | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 1.10 (1.04–1.17) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| P(trend) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.67 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Net wealth:e | ||||||||||||

| <50% | 52.8 (51.7–53.8) | 1.06 (1.04–1.08) | 18.3 (17.4–19.2) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 27.1 (26.1–28.0) | 1.03 (1.00–1.05) | 10.6 (10.0–11.3) | 1.05 (1.02–1.08) | 8.7 (8.2–9.3) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 6.6 (6.2–7.1) | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) |

| >50% | 37.1 (35.9–38.3) | 1.08 (1.05–1.10) | 22.8 (21.7–23.9) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | 13.6 (12.8–14.4) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | 4.0 (3.5–4.4) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 5.6 (5.1–6.2) | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 3.2 (2.8–3.5) | 1.15 (1.08–1.22) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| P(trend) | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.56 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Education level: | ||||||||||||

| <HS | 56.1 (54.8–57.4) | 1.05 (1.03–1.08) | 19.8 (18.6–21.0) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 30.4 (29.1–31.7) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 11.4 (10.6–12.3) | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | 7.9 (7.3–8.6) | 1.00 (0.96–1.05) | 6.3 (5.7–6.9) | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) |

| >HS | 41.5 (40.5–42.6) | 1.07 (1.05–1.09) | 20.4 (19.5–21.3) | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | 17.2 (16.5–18.0) | 1.04 (1.02–1.06) | 6.1 (5.7–6.6) | 1.06 (1.03–1.10) | 7.2 (6.7–7.7) | 0.98 (0.94–1.01) | 4.7 (4.3–5.1) | 1.13 (1.08–1.17) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| P(trend) | 0.52 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.21 | 0.53 | 0.003 | ||||||

Source: Health and Retirement Study, 1998–2012. %= weighted percentage of cohort with caregiving type. HS= high school. OR= odds ratio for the association of two-year increase in time and prevalence of caregiver assistance.

Adjusted by whether respondent is a proxy.

Adjusted for whether respondent is proxy, female, count of ADL/IADL impairments, race, age, net worth, education level.

Interpretation example for the ORs in the model: an average homebound, functionally disabled older adults had 6% greater odds of having caregiver assistance with each incremental biennial survey wave from 1998 to 2012.

Odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval)

Less than the mean of net assets for this cohort, which was equal to $150,000 in 2012 USD.

Ns provided are unweighted.

P-values presented are for the significance of differences in odds ratios across subgroups, with two-sided significance testing.

Discussion

From 1998 to 2012, the percentage of home-dwelling functionally disabled older adults receiving caregiver assistance increased to over 50%. This increased assistance came from multiple sources, including spouses, children, family and paid caregivers. This study adds to others4 by demonstrating increasing rates of caregiver assistance that differed across demographic groups.

The greatest increase in caregiving was among those with fewer ADL and IADL impairments. While this is likely in part because those with more impairments have already sought caregivers, it may also be that more adults with one or two impairments are aging in their communities as opposed to nursing homes. Further work is needed to examine this trend.

This study needs to be interpreted in light of a number of limitations. It relied on self-reported data to assess functional needs and caregiving. Caregiving was measured as ADL and IADL assistance, which is a limited view of the types of help that caregivers provide. We did not have the power to examine the drivers of these trends, such as population changes in illness, insurance, financial resources, social service availability and social networks, nor to detect differences between subgroups for those receiving paid or unpaid care. Further work is needed to assess the balance between functional needs in the population and capacity for caregiver support, as well as the burden on unpaid caregivers.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ankuda is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Dr. Levine is funded by the National Institutes of Aging under grants K23AG040278 and U01 AG09740. The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. Select variables were derived from the RAND HRS Data file, which is an easy to use longitudinal data set based on the HRS data. It was developed at RAND with funding from the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration.

The funders had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Ankuda had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lynn J. Living Long in Fragile Health: The New Demographics Shape End of Life Care. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005 doi: 10.1353/hcr.2005.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knickman JR, Snell EK. The 2030 problem: caring for aging baby boomers. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(4):849–884. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sonnega A, Faul JD, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Phillips JWR, Weir DR. Cohort profile: The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):576–585. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ornstein KA, Leff B, Covinsky KE, et al. Epidemiology of the Homebound Population in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(7):1180–1186. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]