Abstract

Background and Objective

While noninvasive brain stimulation techniques show promise for language recovery after stroke, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We applied inhibitory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) to regions of interest in the right inferior frontal gyrus of patients with chronic poststroke aphasia and examined changes in picture naming performance and cortical activation.

Methods

Nine patients received 10 days of 1-Hz rTMS (Monday through Friday for 2 weeks). We assessed naming performance before and immediately after stimulation on the first and last days of rTMS therapy, and then again at 2 and 6 months post-rTMS. A subset of six of these patients underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging pre-rTMS (baseline) and at 2 and 6 months post-rTMS.

Results

Naming accuracy increased from pre- to post-rTMS on both the first and last days of treatment. We also found naming improvements long after rTMS, with the greatest improvements at 6 months post-rTMS. Long-lasting effects were associated with a posterior shift in the recruitment of the right inferior frontal gyrus: from the more anterior Brodmann area 45 to the more posterior Brodmann areas 6, 44, and 46. The number of left hemispheric regions recruited for naming also increased.

Conclusions

This study found that rTMS to the right hemisphere Broca area homologue confers long-lasting improvements in picture naming performance. The mechanism involves dynamic bilateral neural network changes in language processing, which take place within the right prefrontal cortex and the left hemisphere more generally.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT00608582).

Keywords: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, functional magnetic resonance imaging, neurorehabilitation, neuroplastic mechanisms, aphasia recovery

Aphasia, the acquired loss of language abilities, is one of the most devastating and feared consequences of stroke (Solomon et al, 1994), affecting 15% to 38% of stroke survivors (Berthier, 2005; Wade et al, 1986). In the weeks to months after brain injury, cortical activation patterns associated with language tasks change significantly. Evidence suggests that these tasks can engage both residual left hemisphere language regions and their right hemisphere homologues (Buckner et al, 1996; Gold and Kertesz, 2000; Rosen et al, 2000; Saur et al, 2006; Szaflarski et al, 2013; Warburton et al, 1999; Weiller et al, 1995). In recent years noninvasive brain stimulation (NBS) techniques, such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation, have been used experimentally to help patients with chronic poststroke aphasia recover language abilities (for reviews, see Chrysikou and Hamilton, 2011; Coslett, 2016; Hamilton et al, 2011; Shah et al, 2013). Apparently, NBS promotes neuroplastic changes that improve language processing. However, despite findings demonstrating promising effects of NBS, the neural mechanisms by which focal brain stimulation boosts aphasia recovery remain unclear. The absence of clear principles guiding the application of these treatment approaches limits their clinical use (Turkeltaub, 2015). To better understand how neural stimulation modulates the language network in poststroke aphasia, we combined rTMS with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate changes in the cortical activation patterns associated with picture naming before and after treatment. This work can, by extension, inform the use of NBS in aphasia treatment protocols.

Several studies have used inhibitory rTMS over the right hemisphere homologue of the Broca area in the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) to facilitate naming and other language abilities in people with aphasia (Hamilton et al, 2010; Medina et al, 2012; Naeser et al, 2005a, 2005b, 2010a). Many studies cite the “interhemispheric inhibition hypothesis” in support of this approach. This model assumes that damage to the left hemisphere releases the right hemisphere from transcallosal inhibitory input, resulting in increased right hemisphere activation and, consequently, increased behaviorally deleterious transcallosal inhibition of the already damaged left hemisphere (Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2007). This model is broadly consistent with evidence of beneficial effects from TMS treatments intended to suppress right IFG activity (Naeser et al, 2005a, 2005b) or excite left perilesional cortical activity (Griffis et al, 2016; Szaflarski et al, 2011). This view reflects studies showing a correlation between better aphasia recovery and the reacquisition of perilesional regions for language processing (Postman-Caucheteux et al, 2010; Rosen et al, 2000; Saur et al, 2006; Szaflarski et al, 2013). Thus, most accounts predict that TMS facilitates aphasia recovery by promoting the recruitment of the native language hemisphere and minimizing involvement of the right hemisphere during language processes.

By contrast, data from behavioral, imaging, and TMS studies indicate that the role of the right hemisphere is not just deleterious (Hamilton et al, 2010, 2011; Medina et al, 2012; Turkeltaub et al, 2012). Some evidence suggests that recruitment of right hemispheric homologues of left hemispheric language-related centers could represent a compensatory acquisition or unmasking of language abilities (Buckner et al, 1996; Crosson et al, 2009; Gold and Kertesz, 2000; Xing et al, 2016). Other data indicate that the role of the right hemisphere in aphasia recovery is multifaceted: compensatory in some instances and seemingly deleterious in others (eg, Turkeltaub et al, 2011; Winhuisen et al, 2005, 2007; reviewed in Hamilton et al, 2011). For instance, we have shown that although inhibitory rTMS to the right IFG facilitated naming performance in a patient with a stroke affecting the Broca area, a second stroke affecting the right hemisphere subcortical white matter resulted in a selective decline in language performance (Turkeltaub et al, 2012; see also Basso et al, 1989). Thus, an increasing body of evidence suggests that the role of the right hemisphere in aphasia recovery is complicated.

In light of this conflicting evidence, the primary goal of our experiment was to examine the neural mechanisms underlying long-lasting improvements in naming performance in patients with aphasia treated with inhibitory right IFG rTMS. Our aim was to elucidate the role of right hemisphere language homologues in aphasia recovery. Prior work showed that a single administration of rTMS can have immediate benefits on naming performance, but the effect is only temporary, dissipating within 30 minutes after stimulation (Naeser et al, 2002; see also Naeser et al, 2005a). With administration of rTMS over several days, the beneficial effects can last from 2 to 10 months after stimulation (eg, Hamilton et al, 2010; Medina et al, 2012; Naeser et al, 2005a, 2005b).

In the current study, patients with chronic poststroke aphasia underwent language testing and fMRI imaging once before and 2 and 6 months after a 10-day course of rTMS therapy. We used a stimulation site–finding protocol (previously described by Garcia et al, 2013) to account for individual variability in response to rTMS therapy as a function of functional neuroanatomy and/or lesion location. Combining behavioral testing (naming performance), rTMS, and fMRI, we investigated the brain activation changes associated with sustained behavioral improvement after rTMS. This study provides novel evidence that adds to the current understanding of how TMS promotes long-term neuroplastic changes in the language network of individuals with chronic aphasia. Few previous studies have followed up behavioral changes, and even fewer have followed up behavior-related neural changes for as long a time (6 months) as we report here. As an example, see Martin et al (2009a) for behavioral and accompanying neural changes pre- versus post-TMS in an individual who improved following therapy and one who did not.

In addition, we explored the immediate effects of rTMS therapy by assessing naming performance for repeated and novel stimuli before and immediately after stimulation on the first and last days of treatment. Our purpose was twofold. First, we sought to demonstrate that this treatment approach has an immediate effect on naming performance consistent with evidence presented elsewhere (eg, Martin et al, 2004; Naeser et al, 2002). Showing that would, in turn, support the notion that the sustained naming improvements and associated changes in neural activation patterns observed long after stimulation (ie, 6 months post-rTMS) could be attributed to the rTMS therapy. Second, the presentation of repeated and novel stimuli allowed us to investigate a previously unexamined question: whether the beneficial effects of rTMS therapy on naming generalize to novel stimuli. Typically, researchers investigating the clinical use of rTMS first conduct extensive baseline testing with selected stimuli to establish stable patterns of performance. Then they assess TMS-induced improvements in naming the same stimuli (eg, Barwood et al, 2011; Hamilton et al, 2010; following the protocol described in Martin et al, 2009b, and Naeser et al, 2010b).

In behavioral interventions for aphasia, generalization to untrained language is the gold standard for determining the effectiveness of a particular treatment protocol (eg, Kiran and Bassetto, 2008; Martin et al, 2007; Nickels, 2002). Indeed, some neurostimulation studies have shown improved discourse in conversational speech after rTMS therapy (Hamilton et al, 2010; Medina et al, 2012), suggesting that the beneficial effects of this treatment approach extend beyond picture naming to other aspects of language (for a review, see Naeser et al, 2010b). To our knowledge, however, generalization within the context of naming has yet to be demonstrated with rTMS therapy in the absence of concurrent speech-language therapy (see Cotelli et al, 2011). It is thus difficult to discern how NBS treatment approaches compare with those that have been traditionally used in formal speech-language therapy settings.

Methods

Participants

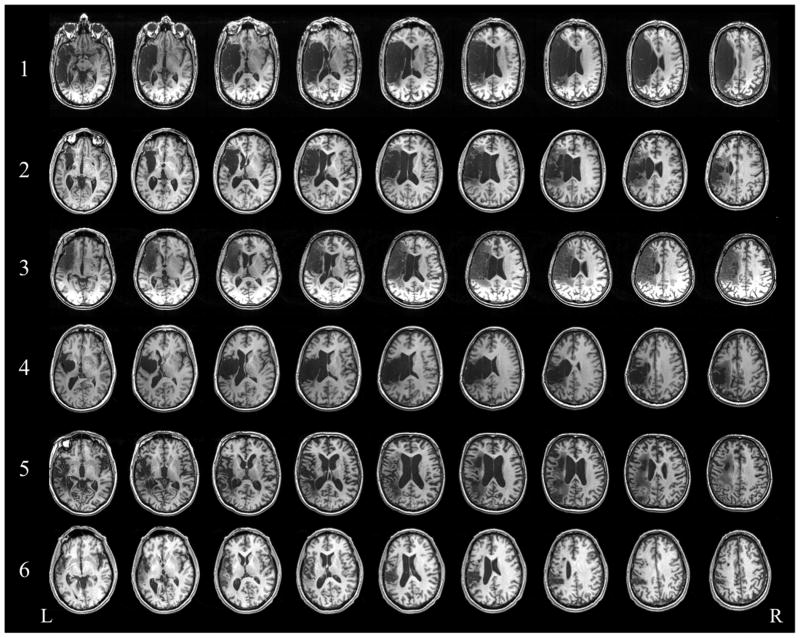

Participants were seven men and two women with chronic poststroke aphasia following a single unilateral ischemic stroke in the left hemisphere. We recruited participants from stroke databases at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) and Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute (Elkins Park, Pennsylvania). The individuals in these databases had given prior consent to be contacted for research opportunities. All participants were right-handed, native English speakers with mild-to-moderate nonfluent aphasia. We instructed our participants not to initiate other forms of speech or language therapy for the duration of the study. Inclusion criteria for our study were relatively intact language comprehension, as defined by performance at or above the 25th percentile on the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass et al, 2001) word comprehension and commands subtests; no other concurrent history of neurologic, psychiatric, or unstable medical conditions; and no contraindications to TMS. In addition, patients had to demonstrate an ability to produce meaningful words and phrases two to four words in length (see Medina et al, 2012, for details on eligibility criteria). The patients' mean age (± standard deviation; range) was 61 years (±8; 47–75); education, 16 years (±4; 12–24); months since onset, 55 (±33; 6–102); and lesion volume, 137 cm3 (±38; 37–252) (Table 1). Of the total group, a subset of six patients completed the combined rTMS/fMRI study. Figure 1 displays structural MRI scans of the six patients' lesions.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients.

| Aphasia Severity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Patient | Sex | Age (years) | Education (years) | Months Since Onset | Mean Phrase Length1 | Naming Ability (maximum = 30)2 | Auditory Comprehension Commands (maximum = 15)1 | Lesion Volume (cm3) | Lesion Distribution | TMS Target |

| 1 | M | 60 | 18 | 87 | 2.5 | 21 | 8 | 252.11 | MCA cortical and subcortical; BA 44, 45, and 47 | rPTr |

| 2 | M | 51 | 14 | 45 | 3.5 | 27 | 15 | 134.03 | Frontoparietal; internal capsule, basal ganglia, BA 44, 45, and 47 | rPOrb |

| 3 | F | 65 | 16 | 20 | 3 | 20 | 8 | 201.62 | MCA cortical and subcortical; BA 44, 45, and 47 | rPTr |

| 4 | M | 47 | 12 | 102 | 2.5 | 26 | 11 | 123.83 | Cortical and subcortical; internal capsule, basal ganglia, thalamus, M1, and BA 44 | rPTr |

| 5 | M | 75 | 18 | 83 | 3 | 21 | 11 | 118.49 | Frontotemporoparietal subcortical; corona radiata | rPTr |

| 6 | M | 60 | 24 | 6 | 3 | 8 | 15 | 36.59 | Frontotemporoparietal cortical and subcortical; corona radiata | rPTr |

| 7* | M | 61 | 18 | 63 | 2 | 7 | 14 | 130.91 | MCA cortical and subcortical; BA 44, 45, and 47 | rPTr |

| 8* | M | 65 | 12 | 29 | 2.5 | 13 | 11 | 53.02 | Subcortical; corona radiata, internal capsule, basal ganglia, and thalamus | rPTr |

| 9* | F | 61 | 14 | 59 | 1 | 17 | 14 | 178.99 | MCA cortical and subcortical; BA 44, 45, and 47 | rPTr |

| Mean ± SD | 61 ± 8 | 16 ± 4 | 55 ± 33 | 2.56 ± 0.73 | 17.78 ± 7.19 | 11.89 ± 2.76 | 137 ± 38 | |||

Patient received rTMS treatment, but did not participate in the fMRI portion of the study.

Scores come from the Cookie Theft Picture Description and Auditory Comprehension Commands subtests of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (Goodglass et al, 2001).

Scores come from the Boston Naming Test (Kaplan et al, 2001).

TMS = transcranial magnetic stimulation. M = male. MCA = middle cerebral artery. rPTr = right pars triangularis. BA = Brodmann area. rPOrb = right pars orbitalis. F = female. M1 = primary motor cortex. SD = standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Structural T1-weighted axial slices depicting lesion location and size in the six patients who participated in the fMRI portion of the study.

The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania institutional review board. Participants provided written informed consent before entering the study. The study was registered through ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT00608582).

Procedures

Naming Assessment and Analyses

To assess the immediate effects of rTMS on naming performance, we asked participants to name 40 pictures selected from the Snodgrass and Vanderwart (1980) picture database before and immediately after rTMS on the first and last days of the 10-day course of rTMS therapy, for a total of 160 naming trials. Twenty of the pictures in each of the four 40-item lists were the same (ie, “repeated”), and the remaining 20 pictures in each list were novel. For one participant (Patient 1), eight items repeated across the four sessions and the number of novel items in each session varied (day 1: pre-rTMS = 12, post-rTMS = 16; day 10: pre-rTMS = 8, post-rTMS = 9) as a result of experimenter error. Repeated and novel pictures presented within and across lists were matched for lexical frequency and visual complexity, and their names were one- or two-syllable words. Pictures were presented in a pseudorandom order with the constraint that no two consecutive words began with the same phoneme or belonged to the same semantic category (described in Hamilton et al, 2010). Pictures assigned to each item type (repeated or novel), day (1 or 10), and stimulation condition (pre- or post-rTMS) were counterbalanced across participants. Data were unavailable from one participant (Patient 7) who did not complete the combined rTMS/fMRI protocol. Responses that deviated from the target response by one phoneme were considered correct. We analyzed the percentage of trials named correctly using a within-subjects repeated-measures analysis of variance with the fixed factors “item type” (repeated, novel), “day” (1, 10), and “stimulation” (pre-rTMS, post-rTMS).

We assessed long-term effects of rTMS therapy on naming performance using the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination's Naming in Categories subtest (Goodglass et al, 2001), a standardized naming assessment that includes three categories (Actions, Animals, and Tools) of 12 items each. Our participants underwent one to four baseline naming sessions (pre-rTMS) to establish a stable measure of performance, with the majority (n = 6) completing three baseline sessions and the others completing one, two, and four sessions each. We tested our participants again at 2 and 6 months post-rTMS. We compared the average percentage of correct picture naming trials across the baseline sessions with the total percentage correct at 2 and 6 months post-rTMS using a within-subjects repeated-measures analysis of variance with the fixed factor “time point” (baseline, 2 months, 6 months). Follow-up paired-samples t tests compared performance at baseline with that at 2 and 6 months post-rTMS separately.

NBS Site Finding and Treatment Procedure

Stimulation was administered with a 70-mm-diameter figure-of-eight coil (Magstim Rapid Transcranial Magnetic Stimulator; Magstim, Whitland, United Kingdom). The Brainsight neuronavigational system (Rogue Research, Montreal, Canada) was used to coregister structural MRI data with the location of the patient and the TMS coil. Participants received rTMS (1 Hz; 90% resting motor threshold) for two phases of the study: optimal site finding (10 minutes of 600 pulses in six sessions) and treatment (20 minutes of 1200 pulses for 10 days). In the optimal site finding phase, participants received rTMS to six different sites within the right frontal lobe in separate sessions to identify a region that, when stimulated, maximally improves naming performance (described in Garcia et al, 2013). Sites included the region of the motor cortex corresponding to the mouth, a site on pars opercularis (Brodmann area [BA] 44), three separate sites on pars triangularis (BA 45; designated in this study as the dorsal posterior, ventral posterior, and anterior pars triangularis), and a site on pars orbitalis (BA 47). Before and immediately after rTMS at each candidate site, participants performed a 40-item picture-naming task. A site was considered to be the optimal target for stimulation if the increase in naming performance from pre- to post-rTMS of that site was greater than two standard deviations from the mean prestimulation performance across all sites (see also Hamilton et al, 2010; Medina et al, 2012; Naeser et al, 2010a; Turkeltaub et al, 2012). Eight of our nine participants responded best to a site within right pars triangularis (rPTr) stimulation; the other one responded best to right pars orbitalis stimulation (Table 1).

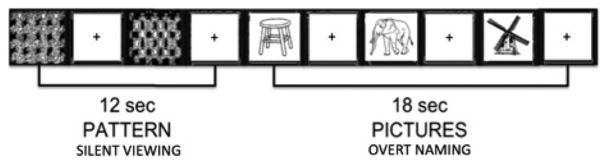

fMRI Procedure and Analyses

We collected fMRI data from six of the nine participants at three time points (pre-rTMS/baseline, 2 and 6 months post-rTMS). We used a block design with two conditions: overt picture naming (experimental condition) and pattern viewing (control condition) (Figure 2). In the experimental condition, patients were presented with a black and white line drawing (taken from Snodgrass and Vanderwart, 1980) and instructed to name the picture aloud. In the control condition, patients were instructed to passively view one of six different black and white checkerboard patterns shown in random order (for details, see Martin et al, 2005, 2009a). Each trial lasted 6 seconds: 1 second for fixation (with a 120-msec audible beep) followed by 5 seconds of picture naming or pattern viewing. Trials were grouped into alternating blocks of picture naming (three trials per block) and pattern viewing (two trials per block). Ten blocks of each condition made up a single run, which lasted 5 minutes and 12 seconds (104 image volumes). All participants completed at least two runs during each fMRI session, with short breaks between runs. For participants who completed more than two runs, we used only the first two in our statistical analyses. We estimated statistical effects in whole-brain analyses using the general linear model. For each participant, a t contrast (experimental versus control) was used to determine task-related functional activation at each time point. Individual t contrasts were combined to identify common regions of activation at the group level, which we conducted separately for each time point. Statistical maps were thresholded at a voxel-wise level of P < 0.001 (uncorrected) and corrected at a cluster level of P < 0.05 using family-wise error.

Figure 2.

Schematic example of the fMRI study using a block design.

fMRI Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Neuroimaging data were collected with a 3.0-T Siemens Trio Scanner (Siemens, Munich, Germany). For each participant, we acquired high-resolution T1-weighted structural images (160 slices, repetition time = 1620, echo time = 3.87 msec, field of view = 192 × 256, 1 × 1 × 1-mm voxels) and an echo planar imaging sequence (31 slices, repetition time = 3000, echo time = 35 msec, field of view = 64 × 64 mm, 3.75 × 3.75 × 4-mm voxels).

We performed preprocessing and statistical analyses of functional images using SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, United Kingdom). There were two regressors of interest (timing parameters for picture naming and pattern viewing) and seven nuisance covariates (six head motion parameters and the intercept) for each run. Images were corrected for motion using a rigid-body six-parameter realignment algorithm, which included correction for jaw motion during speech, enabling the inclusion of fMRI volumes acquired during naming trials in statistical analyses (differing from Martin et al, 2005, 2009a; and Turkeltaub et al, 2012; but similar to Lee et al, 2017). The individual motion-corrected functional images were coregistered to the T1 structural images. Spatial normalization of individual T1 images to the Montreal Neurological Institute T1 template image (Holmes et al, 1998) was carried out in SPM8 and checked for accuracy. For images with poor spatial alignment, the T1 origin was manually reset to the anterior commissure. The normalization process generated spatial transformation parameters, which were applied to the echo planar imaging time series. Spatial smoothing (6-mm full width at half-maximum Gaussian filter) and reslicing resulted in a voxel size of 2 × 2 × 2 mm3. We then estimated statistical effects by using the general linear model.

Results

Effects of rTMS on Naming Performance

Table 2 lists our patients' individual scores on the 40-item picture naming task used to assess immediate effects of rTMS. Table 3 shows their scores on the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination's Naming in Categories subtest (Goodglass et al, 2001) used to assess long-term effects of rTMS.

Table 2. Immediate Effects of rTMS on Naming Performance for Repeated and Novel Stimuli on the First and Last Days of Treatment.

| Patient | Day 1 | Day 10 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||

| Pre-rTMS | Post-rTMS | Pre-rTMS | Post-rTMS | |||||||||

| Repeated | Novel | Total | Repeated | Novel | Total | Repeated | Novel | Total | Repeated | Novel | Total | |

| 1 | 38 | 17 | 25 | 75 | 50 | 58 | 75 | 38 | 56 | 75 | 56 | 65 |

| 2 | 55 | 65 | 60 | 65 | 85 | 75 | 60 | 65 | 63 | 60 | 65 | 63 |

| 3 | 40 | 35 | 38 | 60 | 55 | 58 | 35 | 30 | 33 | 40 | 50 | 45 |

| 4 | 45 | 65 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 63 | 50 | 35 | 43 | 55 | 35 | 45 |

| 5 | 40 | 60 | 50 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 55 | 60 | 58 | 55 | 70 | 63 |

| 6 | 10 | 40 | 25 | 15 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 18 | 25 | 40 | 33 |

| 8* | 40 | 30 | 35 | 25 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 35 | 30 | 30 | 50 | 40 |

| 9* | 45 | 35 | 40 | 50 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 35 | 43 | 55 | 50 | 53 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Mean | 39 | 43 | 41 | 49 | 49 | 49 | 46 | 40 | 43 | 49 | 52 | 51 |

Data were unavailable for Patient 7. Scores reflect percent accuracy, and scores in bold (totals) reflect percent accuracy collapsed across repeated and novel stimuli.

Patient received rTMS treatment, but did not participate in the fMRI portion of the study.

rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Table 3. Long-Term Effects of Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) on the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination's Naming in Categories Subtest Scores.

| Patient | Score* by Baseline Session | Score* 2 Months Post-rTMS | Score* 6 Months Post-rTMS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | |||

| 1 | 47 | NA | NA | NA | 47 | 56 | 67 |

| 2 | 86 | 86 | NA | NA | 86 | 89 | 92 |

| 3 | 61 | 50 | 58 | NA | 56 | 58 | 75 |

| 4 | 67 | 78 | 64 | NA | 69 | 72 | 89 |

| 5 | 69 | 67 | 81 | NA | 72 | 75 | 72 |

| 6 | 36 | 42 | 39 | NA | 39 | 33 | 67 |

| 7† | 28 | 33 | 39 | NA | 33 | 53 | 61 |

| 8† | 44 | 50 | 39 | NA | 44 | 50 | 47 |

| 9† | 33 | 53 | 64 | 53 | 51 | 53 | 86 |

|

| |||||||

| Mean | 55 | 60 | 73 | ||||

Scores reflect percent accuracy. The majority of patients (n = 6) completed three baseline sessions, whereas the others (n = 3) completed one, two, and four baseline sessions.

Patient received rTMS treatment, but did not participate in the fMRI portion of the study.

NA = not applicable.

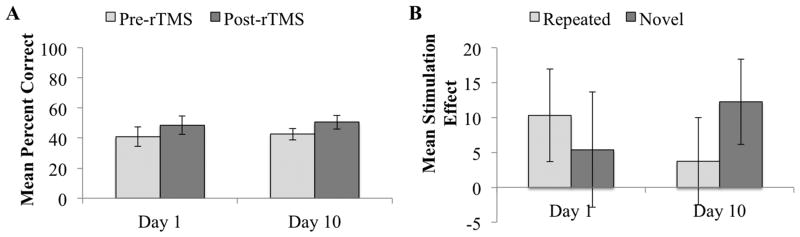

The analysis assessing the immediate effects of rTMS on naming performance revealed a main effect of stimulation (F1,7 = 8.98, P = 0.02), demonstrating that naming accuracy increased from pre- to post-rTMS (collapsed across repeated and novel stimuli; see Figure 3A). We also found a three-way interaction between item type, day, and stimulation (F1,7 = 5.65, P < 0.05). As shown in Figure 3B, the three-way interaction reflects a larger stimulation effect for repeated than for novel items on day 1 of stimulation. The opposite was true on day 10 of stimulation, when the effect was larger for novel than for repeated items. No other main effects or interactions were significant (all P values > 0.49). Analyses assessing only those six participants who completed the combined rTMS/fMRI study revealed the same pattern of results: a main effect of stimulation (F1,5 = 7.63, P = 0.04) and a three-way interaction between item type, day, and stimulation (F1,5 = 6.89, P < 0.05), but no other significant main effects or interactions (all P values > 0.18).

Figure 3.

Behavioral results showing the immediate effects of rTMS therapy. A: Mean percent correct (collapsed across repeated and novel items) and associated within-subjects 95% confidence intervals for pre-rTMS and post-rTMS performance on the first and last days of treatment. B: Mean stimulation effect (difference between post-rTMS and pre-rTMS mean naming accuracy) and associated within-subjects 95% confidence intervals for repeated and novel items on the first and last days of treatment.

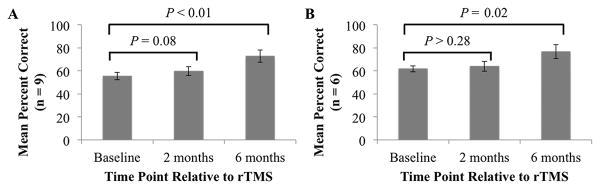

Analyses assessing long-term effects of rTMS therapy revealed that naming performance changed significantly across the three time points (F2,16 = 11.59, P < 0.001). Follow-up comparisons revealed that the beneficial effect of rTMS on naming accuracy was marginal at 2 months (t8 = –1.98, P = 0.08) and significant at 6 months post-rTMS (t8 = –4.25, P < 0.01) compared to average baseline performance (Figure 4A). Naming performance in the six patients who underwent fMRI scanning also changed significantly across the three time points (F2,10 = 8.45, P < 0.01). However, follow-up comparisons revealed that naming performance in these patients did not significantly differ at 2 months versus baseline (t5 = –1.19, P > 0.28), but did significantly improve at 6 months post-rTMS versus baseline (t5 = –3.60, P = 0.02) (Figure 4B). We therefore examined regions that were recruited during picture naming versus pattern viewing pre-rTMS (baseline) versus 6 months post-rTMS.

Figure 4.

Behavioral results showing long-term effects of rTMS therapy. A: Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination naming performance and associated within-subjects 95% confidence intervals at baseline and 2 and 6 months post-rTMS for all patients (n = 9). B: Results for the subset of patients who participated in the fMRI portion of the study (n = 6).

fMRI Analyses of Brain Activity

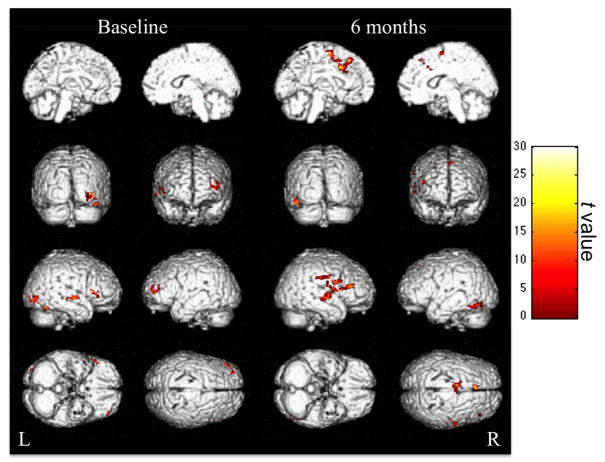

The fMRI analyses revealed bilateral changes in the regions recruited for picture naming at the two time points (Figure 5). Table 4 lists all regions significantly more active for picture naming than for pattern viewing at baseline and 6 months post-rTMS. At both time points, the right superior temporal gyrus and right IFG were more active for picture naming than for pattern viewing. Critically, however, picture naming and pattern viewing recruited two different regions within the right IFG at each time point. The rPTr (BA 45) was significantly more active for picture naming than for pattern viewing at baseline, but not at 6 months post-rTMS, when naming improvements manifested behaviorally. Instead, a more posterior region within the right IFG, pars opercularis (rPOp; BA 6/44/46), was more active for picture naming than for pattern viewing at 6 months post-rTMS.

Figure 5.

Neuroimaging results. Regions significantly more active for picture naming than for pattern viewing at baseline (8 images on the left) and 6 months post-rTMS (8 images on the right) found in the group analyses of the subset of patients who participated in the fMRI portion of the study (n = 6). Color maps correspond to the t values reflecting the picture naming versus pattern viewing contrast at each time point after thresholding at a voxel-wise level of P < 0.001 (uncorrected) and cluster level of P < 0.05 (family-wise error). Brighter colors represent higher t values.

Table 4. Regions Exhibiting Significantly More Activation on fMRI for Picture Naming Than for Pattern Viewing at Baseline (Pre-rTMS) and 6 Months Post-rTMS in a Subset of 6 Patients.

| Time | Cluster | Brodmann Area | Cluster Size (k) | t (peak) | MNI Peak Coordinate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FWE-Corrected P | x | y | z | |||||

| Baseline | R occipital | 19 | 89 | 19.56 | 0.018 | 40 | –80 | –6 |

| R superior and middle temporal gyri | 21, 22 | 77 | 19.58 | 0.011 | 58 | –12 | –2 | |

| R fusiform and parahippocampal gyri | 37 | 70 | 10.04 | 0.022 | 34 | –42 | –14 | |

| R inferior frontal gyrus | 45 | 65 | 14.49 | 0.024 | 52 | 22 | 8 | |

| L middle frontal gyrus | 10 | 62 | 16.97 | 0.033 | –40 | 52 | 8 | |

|

| ||||||||

| 6 months | L medial frontal and cingulate gyri, supplemental motor area | 6, 8, 32 | 410 | 28.29 | 0.000 | –6 | 28 | 50 |

| R superior temporal gyrus, precentral gyrus, and inferior frontal gyrus | 22, 6, 44 | 313 | 30.77 | 0.000 | 52 | –14 | –2 | |

| R inferior frontal gyrus | 44, 46 | 148 | 16.56 | 0.000 | 40 | 30 | 16 | |

| L temporal, occipital, and fusiform gyri | 37 | 103 | 12.85 | 0.004 | –42 | –74 | –18 | |

fMRI = functional magnetic resonance imaging. rTMS = repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. MNI = Montreal Neurological Institute. FWE = family-wise error. R = right. L = left.

Moreover, at baseline, the majority of regions with greater activation for picture naming than for pattern viewing were located in the right hemisphere (ie, right occipital, fusiform, parahippocampal, and middle temporal gyri), with the exception of one frontal region, the left middle frontal gyrus. At 6 months post-rTMS, by contrast, the regions with greater activation for picture naming than for pattern viewing were largely left lateralized, with the exception of the rPOp and right superior temporal gyrus mentioned above. These left hemisphere regions included the left medial frontal and cingulate gyri, supplemental motor area, and fusiform gyrus.

It is worth noting that the group-level analyses are subject to the heterogeneity of lesion size and location among participants. That is, these analyses excluded voxels in which a lesion was present in at least one participant. Consequently, we cannot draw inferences about perilesional activation on a participant-by-participant basis. However, because the same lesioned voxels were excluded in both the baseline and 6-month group-level analyses, we can be confident that the overall increase in the number of left hemispheric regions recruited for naming post-rTMS reflects bilateral changes in the neural network recruited for language.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the neural substrates of long-term naming improvements following a course of rTMS in patients with poststroke aphasia. The behavioral findings revealed that inhibitory rTMS to the right IFG persistently improved naming performance, which was most apparent 6 months after stimulation. We attribute this long-lasting improvement in naming abilities to the stimulation itself, rather than some other coincidental factor that could potentially influence language performance at later time points, for two reasons. First, we found an immediate effect of rTMS on naming, whereby participants were more accurate in naming pictures immediately after, as compared to before, the application of stimulation, consistent with evidence presented elsewhere (eg, Naeser et al, 2002). Second, to the best of our knowledge, our patients did not undergo other forms of therapy during this study, and so had no concurrent behavioral treatments that might have increased their naming accuracy 6 months after rTMS. The neuroimaging findings demonstrated that the patients' improvements were associated with 1) a posterior shift in the recruitment of the right IFG for picture naming and 2) the recruitment of bilateral regions different from those recruited for picture naming before rTMS. Importantly, these findings suggest that rTMS to the right IFG facilitates naming in aphasia by modulating the recruitment of right hemisphere regions for word retrieval, rather than suppressing the involvement of the right hemisphere more globally. Together, our results suggest that this neuromodulation approach confers long-lasting benefits by inducing a dynamic process of neural network reorganization that requires time to manifest behaviorally.

Our findings provide evidence against the purported mechanism by which TMS is thought to enhance aphasia recovery. Previous studies using TMS as an aphasia treatment have applied either inhibitory stimulation to the right prefrontal cortex (Winhuisen et al, 2005, 2007) or excitatory stimulation to the left prefrontal cortex (Griffis et al, 2016; Szaflarski et al, 2011) under the assumption that right hemisphere recruitment is generally maladaptive in aphasia recovery. In particular, this model predicts that suppressing the right IFG, as was done in the current study, should produce language gains by releasing the left hemisphere from the transcallosal inhibitory effects of the overactive right hemisphere, thereby allowing the left hemisphere to reacquire language function (Fregni and Pascual-Leone, 2007). However, we found that improved naming performance 6 months post-rTMS was associated with activity in a region within the right IFG. Thus, these findings are not consistent with the assumption that activation of the right hemisphere for language tasks is detrimental to aphasia recovery, and suggest instead that right hemisphere language homologues may compensate for the stroke-caused loss of language function in the native left hemisphere.

Importantly, our results support a growing body of research indicating that the role of the right hemisphere in aphasia recovery is multifaceted (Hamilton et al, 2011; Turkeltaub et al, 2011, 2012). We found that rTMS-induced naming improvements were associated with the recruitment of a right IFG region (ie, rPOp) located more posteriorly to that which was recruited at baseline (ie, rPTr). This suggests that the rPTr may be ineffective at compensating for language processes following stroke. Consistent with this finding, previous studies have found that inhibiting the rPTr as opposed to other regions within the right hemisphere is most often associated with the best language outcomes, whereas inhibiting other regions often has a negative or null effect on performance (Hamilton et al, 2010; Martin et al, 2009b; Naeser et al, 2005a, 2005b).

Further, a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies revealed that patients with left IFG damage tended to recruit homologous right IFG regions for language tasks. Moreover, although most right IFG regions were functionally homologous to their left hemisphere counterparts, this was not the case for the rPTr. The right rPOp, however, is functionally homologous to its left hemisphere counterpart, suggesting that this region may be recruited in a compensatory fashion to perform the role of the lesioned node (Turkeltaub et al, 2011). TMS therapy may allow this region to assume language processes by inhibiting the deleterious recruitment of the rPTr. Thus, our finding that post-rTMS naming improvements were associated with increased recruitment of the rPOp indicates that this region may be functionally better suited to assume language functions than other regions within the right IFG. Taken together, our fMRI results are consistent with the idea that some regions within the right IFG support aphasia recovery while other right IFG regions may interfere with this process.

Another interesting aspect of our results is that the behavioral benefits of TMS increased with time. The behavioral findings reinforce prior studies showing that the therapeutic benefit of rTMS in poststroke aphasia treatment can last for 2 to 10 months after stimulation (Medina et al, 2012; Turkeltaub et al, 2012). This benefit becomes more pronounced over time (Hamilton et al, 2010; Naeser et al, 2005a, 2005b). Our fMRI findings suggest that the behavioral benefits of TMS that emerge over time arise from the functional reorganization of language within the right hemisphere homologue of the Broca area. There are two possible, not mutually exclusive, explanations of the long-lasting and increasingly beneficial effects of rTMS on naming performance. One is that TMS-induced functional reorganization permits more effective recruitment of right hemispheric regions that are well suited for naming. The other is that stimulating a given region within the intact hemisphere “resets” the maladaptive language network in place after a stroke by inducing neuroplastic changes across the network via corticocortical connections (eg, Devlin and Watkins, 2007; Hamilton et al, 2010; Ilmoniemi et al, 1997). This hypothesis is supported by the finding that neural activity pre- versus post-rTMS treatment featured an increase in the number of left hemisphere regions recruited for picture naming.

Consistent with our findings, previous studies examining the neural substrates of word retrieval improvements following speech-language therapy have also found a posterior shift in right IFG activity (Crosson et al, 2009) and increased activity in perilesional regions (Meinzer et al, 2008). Further, the findings presented here complement those of a previous study that investigated the neural mechanisms of spontaneous aphasia recovery from the acute to the chronic phase and found an initial increase in right IFG (rPTr and rPOp) activity followed by a later shift in activation toward left hemispheric perilesional regions (Saur et al, 2006). This bilateral shift in neural activation patterns is similar to what we observed in patients with chronic aphasia 6 months post-rTMS as compared to baseline.

This may suggest that optimal recovery mechanisms (ie, additional recruitment of perilesional regions) for some people with aphasia may fail to occur spontaneously in the subacute time period after stroke, but can be facilitated by the application of rTMS therapy. Thus, the neural mechanisms of TMS-induced recovery may overlap to some extent with those that occur during the natural course of recovery. In turn, the results presented here support the idea that bilateral language networks play an important role in aphasia recovery. The data further indicate that rTMS to a given region invokes a cascade of events downstream, which likely starts the dynamic process of bilateral functional reorganization of the language network.

Importantly, we provide new insight into the effectiveness of rTMS therapy in facilitating word retrieval by demonstrating that this treatment protocol confers naming benefits that generalize to novel stimuli over the 10-day course of treatment. That is, naming improvements for repeated stimuli were greatest following rTMS on the first day of stimuli; however, rTMS had greater effects for novel stimuli on the last day of stimulation. Because the repeated and novel stimuli were carefully matched for difficulty and counterbalanced across participants, it is likely that the differential benefits occurring on the first versus last day of stimulation were due to the rTMS itself. Intuitively, it might be expected that TMS-induced naming improvements for repeated items would plateau over the course of treatment. Any improvements observed on the first day after stimulation would likely be present on the last day before stimulation, making it difficult to observe a pre-/post-rTMS difference in performance on the last day of stimulation. By contrast, TMS conferred generalization with respect to naming novel stimuli by the end of a 10-day course of treatment (but not after only 1 day of treatment).

As noted previously, the effectiveness of an aphasia treatment protocol is often determined by its generalization to related language stimuli and tasks (eg, Kiran and Bassetto, 2008). To date, however, few studies employing neuromodulation techniques like TMS or transcranial direct current stimulation have assessed whether these treatment approaches generalize. A few studies have shown that rTMS combined with behavioral interventions leads to generalization in naming tasks (Cotelli et al, 2011; see Tippett et al, 2015, for evidence of generalization in patients with primary progressive aphasia following transcranial direct current stimulation). Here, we extend findings from previous research, demonstrating that rTMS therapy can also improve naming performance for novel items in the absence of concurrent speech-language therapy when administered across several days.

Of note, we examined generalization for only the first and last days of the 10-day course of rTMS therapy. Research using behavioral interventions has found that generalization to novel (untrained) stimuli is a short-lived effect, with larger and long-lasting treatment effects for those items that were trained in the treatment protocol (for reviews, see Kiran and Bassetto, 2008; Nickels, 2002). Future studies will need to establish whether NBS treatment approaches, whether administered concurrently with behavioral treatments (eg, Tippett et al, 2015) or alone, confer more robust and persistent generalization effects. Determining this has the potential to inform the development of optimal treatment protocols that best utilize resources and time.

Finally, it is important to note that our patients differed in their response to rTMS therapy, which may reflect differences in neuroplastic mechanisms of language recovery (Hamilton et al, 2011; Heiss and Thiel, 2006; Martin et al, 2009a; Shah-Basak et al, 2015; Torres et al, 2013). For instance, time since stroke and lesion distribution have been shown to affect neuroplastic changes in the cortical network underpinning language recovery (eg, Saur et al, 2006). This in turn may influence how individuals respond to NBS treatment (Shah-Basak et al, 2015; for reviews, see Hamilton et al, 2011; Heiss and Thiel, 2006; Torres et al, 2013). We assessed whether time since stroke and/or lesion size accounted for variability in response to rTMS among our participants, but did not find a significant relationship between rTMS response (calculated as percent increase in naming performance from baseline to 2 and 6 months post-rTMS) and time since stroke (all r values < 0.31 and P values > 0.42) or lesion volume (all r values < 0.23 and P values > 0.57) at either time point.

Lesion location, rather than lesion size, may be a better predictor of response to rTMS therapy, as the specific regions affected by stroke may affect the capacity for functional reorganization of language processes. Indeed, evidence that lesion location might play a role in a person's response to TMS therapy has been reported (Martin et al, 2009a), and may provide an explanation for the variability in TMS responses that we found.

Our sample size is likely not sufficient to reliably assess whether variable responses to TMS therapy were due to differences in lesion location and/or other factors affecting neuroplastic mechanisms in aphasia, such as lesion size and time since stroke. In the future, it will be important to conduct larger-scale studies that have the power to account for such variables in predicting individual responsiveness to NBS treatment protocols in aphasia. Such information is needed for optimal stratification of these treatment approaches.

To our knowledge, this is one of only a few studies to investigate not only neural changes after rTMS of the right IFG in patients with chronic aphasia but also whether rTMS therapy confers generalization to novel stimuli within the context of naming. Moreover, it is the first to do so in the absence of concurrent formal speech-language therapy (eg, Griffis et al, 2016; Hara et al, 2015).

While our findings are promising, the study had limitations that should be considered. First, participants named the same items across the behavioral testing sessions of interest with respect to neuroimaging data collection, potentially introducing practice effects. This seems an unlikely explanation for our findings given that most patients exhibited stable performance across all pre-rTMS (baseline) sessions, and our results revealed TMS-induced naming improvements for novel stimuli. A second limitation is that the control task, pattern viewing, may not have been ideal for isolating the cortical network underpinning picture naming. It does not control for other processes potentially involved in naming pictures (eg, attentional demand and/or motor speech processes) not of interest in the current study. However, given the correspondence between the regions identified here and prior work using fMRI in stroke aphasia (eg, Rosen et al, 2000; Saur et al, 2006), we can be fairly confident that our results represent neural activation patterns associated with picture naming. Third, the fMRI analyses may have been underpowered, as only six patients participated in this portion of the protocol, potentially limiting our ability to detect changes in the left hemisphere because of the effects of infarctions. Finally, our study did not include a control group. Future work must replicate and extend these findings.

In conclusion, the persistence of rTMS treatment effects and associated cortical activation patterns found in the current study are of critical interest in the neurorehabilitation of aphasia because they suggest that the effects of rTMS on the right IFG 1) reinforce themselves over time even without additional treatment, 2) prompt a bilateral shift in the recruitment of language regions, and, critically, 3) modulate the recruitment of regions within the right IFG, rather than suppressing it entirely. These findings provide insight into the neuroplastic mechanisms underlying language recovery and how complex neural systems can be altered focally to enhance recovery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients who generously gave their time and thereby contributed to this research.

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1DC005672, K01NS060995) and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (20417) to R.H.H, and the National Institutes of Health (KL2TR000102) and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation (2012062) to P.E.T.

Glossary

- BA

Brodmann area

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- IFG

inferior frontal gyrus

- NBS

noninvasive brain stimulation

- rPOp

right pars opercularis

- rPTr

right pars triangularis

- rTMS

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Barwood CH, Murdoch BE, Whelan BM, et al. The effects of low frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and sham condition rTMS on behavioural language in chronic non-fluent aphasia: short term outcomes. NeuroRehabilitation. 2011;28:113–128. doi: 10.3233/NRE-2011-0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basso A, Gardelli M, Grassi MP, et al. The role of the right hemisphere in recovery from aphasia: two case studies. Cortex. 1989;25:555–566. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(89)80017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier ML. Poststroke aphasia. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:163–182. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner RL, Corbetta M, Schatz J, et al. Preserved speech abilities and compensation following prefrontal damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1249–1253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysikou EG, Hamilton RH. Noninvasive brain stimulation in the treatment of aphasia: exploring interhemispheric relationships and their implications for neurorehabilitation. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2011;29:375–394. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2011-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coslett HB. Noninvasive brain stimulation in aphasia therapy: lessons from TMS and tDCS. In: Hickok G, Smalls SL, editors. Neurobiology of Language. New York, New York: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 1035–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Cotelli M, Fertonani A, Miozzo A, et al. Anomia training and brain stimulation in chronic aphasia. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2011;21:717–741. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2011.621275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosson B, Moore AB, McGregor KM, et al. Regional changes in word-production laterality after a naming treatment designed to produce a rightward shift in frontal activity. Brain Lang. 2009;111:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin JT, Watkins KE. Stimulating language: insights from TMS. Brain. 2007;130:610–622. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fregni F, Pascual-Leone A. Technology insight: noninvasive brain stimulation in neurology—perspectives on the therapeutic potential of rTMS and tDCS. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:383–393. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, Norise C, Faseyitan O, et al. Utilizing repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to improve language function in stroke patients with chronic non-fluent aphasia. J Vis Exp. 2013;77:e50228. doi: 10.3791/50228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BT, Kertesz A. Right hemisphere semantic processing of visual words in an aphasic patient: an fMRI study. Brain Lang. 2000;73:456–465. doi: 10.1006/brln.2000.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodglass H, Kaplan E, Barresi B. The Assessment of Aphasia and Related Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Griffis JC, Nenert R, Allendorfer JB, et al. Interhemispheric plasticity following intermittent theta burst stimulation in chronic poststroke aphasia. Neural Plast. 2016;2016(2016):4796906. doi: 10.1155/2016/4796906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RH, Chrysikou EG, Coslett B. Mechanisms of aphasia recovery after stroke and the role of noninvasive brain stimulation. Brain Lang. 2011;118:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton RH, Sanders L, Benson J, et al. Stimulating conversation: enhancement of elicited propositional speech in a patient with chronic non-fluent aphasia following transcranial magnetic stimulation. Brain Lang. 2010;113:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Abo M, Kobayashi K, et al. Effects of low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with intensive speech therapy on cerebral blood flow in post-stroke aphasia. Transl Stroke Res. 2015;6:365–374. doi: 10.1007/s12975-015-0417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiss WD, Thiel A. A proposed regional hierarchy in recovery of post-stroke aphasia. Brain Lang. 2006;98:118–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes CJ, Hoge R, Collins L, et al. Enhancement of MR images using registration for signal averaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1998;22:324–333. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199803000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilmoniemi RJ, Virtanen J, Ruohonen J, et al. Neuronal responses to magnetic stimulation reveal cortical reactivity and connectivity. Neuroreport. 1997;8:3537–3540. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199711100-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan E, Goodglass H, Weintraub S. Boston Naming Test. 2nd ed. Austin, Texas: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kiran S, Bassetto G. Evaluating the effectiveness of semantic-based treatment for naming deficits in aphasia: what works? Semin Speech Lang. 2008;29:71–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1061626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Zreik JT, Hamilton RH. Patterns of neural activity predict picture-naming performance of a patient with chronic aphasia. Neuropsychologia. 2017;94:52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin N, Thompson CK, Worrall L. Aphasia Rehabilitation: The Impairment and Its Consequences. San Diego, California: Plural Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PI, Naeser MA, Doron KW, et al. Overt naming in aphasia studied with a functional MRI hemodynamic delay design. Neuroimage. 2005;28:194–204. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PI, Naeser MA, Ho M, et al. Overt naming fMRI pre- and post-TMS: two nonfluent aphasia patients, with and without improved naming post-TMS. Brain Lang. 2009a;111:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PI, Naeser MA, Ho M, et al. Research with transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of aphasia. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2009b;9:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s11910-009-0067-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PI, Naeser MA, Theoret H, et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation as a complementary treatment for aphasia. Semin Speech Lang. 2004;25:181–191. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-825654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina J, Norise C, Faseyitan O, et al. Finding the right words: transcranial magnetic stimulation improves discourse productivity in non-fluent aphasia after stroke. Aphasiology. 2012;26:1153–1168. doi: 10.1080/02687038.2012.710316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinzer M, Flaisch T, Breitenstein C, et al. Functional re-recruitment of dysfunctional brain areas predicts language recovery in chronic aphasia. Neuroimage. 2008;39:2038–2046. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeser M, Theoret H, Kobayashi M, et al. Modulation of cortical areas with repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation to improve naming in nonfluent aphasia. NeuroImage. 2002;16(Suppl 1) [abstract 133] [Google Scholar]

- Naeser MA, Martin PI, Lundgren K, et al. Improved language in a chronic nonfluent aphasia patient following treatment with CPAP and TMS. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2010a;23:29–28. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181bf2d20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeser MA, Martin PI, Nicholas M, et al. Improved picture naming in chronic aphasia after TMS to part of right Broca's area: an open-protocol study. Brain Lang. 2005a;93:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeser MA, Martin PI, Nicholas M, et al. Improved naming after TMS treatments in a chronic, global aphasia patient—case report. Neurocase. 2005b;11:182–193. doi: 10.1080/13554790590944663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naeser MA, Martin PI, Treglia E, et al. Research with rTMS in the treatment of aphasia. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2010b;28:511–529. doi: 10.3233/RNN-2010-0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickels L. Therapy for naming disorders: revisiting, revising, and reviewing. Aphasiology. 2002;16:935–979. [Google Scholar]

- Postman-Caucheteux WA, Birn RM, Pursley RH, et al. Single-trial fMRI shows contralesional activity linked to overt naming errors in chronic aphasic patients. J Cogn Neurosci. 2010;22:1299–1318. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen HJ, Petersen SE, Linenweber MR, et al. Neural correlates of recovery from aphasia after damage to left inferior frontal cortex. Neurology. 2000;55:1883–1894. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.12.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saur D, Lange R, Baumgaertner A, et al. Dynamics of language reorganization after stroke. Brain. 2006;129:1371–1384. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PP, Szaflarski JP, Allendorfer J, et al. Induction of neuroplasticity and recovery in post-stroke aphasia by non-invasive brain stimulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah-Basak PP, Norise C, Garcia G, et al. Individualized treatment with transcranial direct current stimulation in patients with chronic non-fluent aphasia due to stroke. Front Hum Neurosci. 2015;9:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass J, Vanderwart MA. A standardized set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity and visual complexity. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn. 1980;6:174–215. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.6.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon NA, Glick HA, Russo CJ, et al. Patient preferences for stroke outcomes. Stroke. 1994;25:1721–1725. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.9.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Allendorfer JB, Banks C, et al. Recovered vs. not-recovered from post-stroke aphasia: the contributions from the dominant and non-dominant hemispheres. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31:347–360. doi: 10.3233/RNN-120267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaflarski JP, Vannest J, Wu SW, et al. Excitatory repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation induces improvements in chronic post-stroke aphasia. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:CR132–CR139. doi: 10.12659/MSM.881446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippett DC, Hillis AE, Tsapkini K. Treatment of primary progressive aphasia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2015;17:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11940-015-0362-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J, Drebing D, Hamilton R. TMS and tDCS in post-stroke aphasia: integrating novel treatment approaches with mechanisms of plasticity. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2013;31:501–515. doi: 10.3233/RNN-130314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkeltaub PE. Brain stimulation and the role of the right hemisphere in aphasia recovery. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2015;15:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11910-015-0593-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkeltaub PE, Coslett HB, Thomas AL, et al. The right hemisphere is not unitary in its role in aphasia recovery. Cortex. 2012;48:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkeltaub PE, Messing S, Norise C, et al. Are networks for residual language function and recovery consistent across aphasic patients? Neurology. 2011;76:1726–1734. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821a44c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade DT, Hewer RL, David RM, et al. Aphasia after stroke: natural history and associated deficits. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:11–16. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.49.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warburton E, Price CJ, Swinburn K, et al. Mechanisms of recovery from aphasia: evidence from positron emission tomography studies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:155–161. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiller C, Isensee C, Rijntjes M, et al. Recovery from Wernicke's aphasia: a positron emission tomographic study. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:723–732. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhuisen L, Thiel A, Schumacher B, et al. Role of the contralateral inferior frontal gyrus in recovery of language function in poststroke aphasia: a combined repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and positron emission tomography study. Stroke. 2005;36:1759–1763. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174487.81126.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winhuisen L, Thiel A, Schumacher B, et al. The right inferior frontal gyrus and poststroke aphasia: a follow-up investigation. Stroke. 2007;38:1286–1292. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000259632.04324.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing S, Lacey EH, Skipper-Kallal LM, et al. Right hemisphere grey matter structure and language outcomes in chronic left hemisphere stroke. Brain. 2016;139:227–241. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]