Abstract

Background/Objective

Controversy exists over whether proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) increase risk for dementia. This study examined the risk associated with PPIs on conversion to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), dementia, and specifically Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Design

Observational, longitudinal study.

Setting

Tertiary academic Alzheimer Disease research centers funded by the National Institute on Aging.

Participants

Research volunteers ≥ 50 years old with 2 to 6 annual visits. Eight hundred and eighty four were taking PPIs at every visit, 1,925 took PPIs intermittently, whereas 7,677 never reported taking PPIs. All had baseline normal cognition or MCI.

Analytic Plan

Multivariable Cox regression analyses evaluated the association between PPI use and annual conversion of baseline normal cognition into MCI or dementia, or annual conversion of baseline MCI into dementia, controlling for demographics, vascular comorbidities, mood, and anticholinergics and histamine-2 receptor antagonists.

Results

Continuous (Always vs. Never) PPI use was associated with a decreased risk of decline in cognitive function (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.66–0.93, p=.005) and decreased risk of conversion to MCI or dementia due to AD (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69–0.98, p=.026). Intermittent use was also associated with decreased risk of decline in cognitive function (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.76–0.93), p=.001) and risk of conversion to MCI or dementia due to AD (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.91), p=.001). This reduced risk was found for persons with either normal cognition or MCI.

Conclusion

PPIs were not associated with greater risk of dementia or of AD, in contrast to recent reports. Study limitations include reliance on self-reported PPI use and the lack of dispensing data. Prospective studies are needed to confirm these results in order to guide empirically based clinical treatment recommendations.

Keywords: Proton Pump Inhibitors, Cognitive Functioning, Mild Cognitive Impairment, Alzheimer’s Disease

INTRODUCTION

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are a class of drugs prescribed to treat gastrointestinal disorders such as duodenal ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease by reducing gastric acid secretion. The safety of PPIs with respect to cognitive functioning, including the risk for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, has recently been questioned. Two studies reported a detrimental impact of PPIs in increasing the risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in persons ≥ 75 years of age, raising concerns about their widespread use among older adults.1,2 Haenisch and colleagues’2 investigation included 3,076 persons (23% PPI users) who were enrolled in the multicenter German Study of Aging, Cognition and Dementia in Primary Care Patients. These community residing participants were ≥ 75 years and were judged to be non-demented at baseline as determined by a battery of measures from the Structured Interview for Diagnosis of Dementia of Alzheimer type, Multi-infarct Dementia and Dementia of other Aetiology (SIDAM)3 consisting of the Mini-Mental State Examination, activities of daily living scale, and the Hachinski-Rosen Scale. These measures were repeated at 18 month intervals. The investigators found an increased risk of both dementia (HR 1.38, 95% CI 1.04–1.83, p=.02) and AD (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.01–2.06, p=.04) in PPI users compared to non-users over a follow-up interval of 72 months. A subsequent study by the same investigators1 utilized the claims data of the largest healthcare insurance company in Germany. The inpatient and outpatient diagnoses over a seven year period were examined for 73,679 individuals (4% PPI users) ≥ 75 years old with and without a dementia diagnosis at baseline. PPI users had a significantly increased risk of incident dementia compared to non-users (HR 1.44, 95% CI 1.36–1.52, p<.001).

As noted by Kuller,4 the finding of a 1.4 increased risk for dementia with PPI use in the studies by Haenish and colleagues would confer an increase of 10,000 new cases of dementia each year in persons 75–84 years old. However, a recent case control study5 on risk factors for dementia, also conducted in Germany, did not observe an increased risk. Booker and colleagues obtained general practitioner medical record information from a database of patients 70–90 years old with a diagnosis of dementia (n=11,956; % PPI use=44.3) or without a diagnosis of dementia (n=11,956, % PPI use=45.8) over a five year period. PPIs were associated with a decreased risk of developing dementia (HR 0.93, 95% CI 0.90–0.97).

PPI use has risen in the United States, as reported in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in which the prevalence of prescription PPIs significantly increased from 4.9–8.3 in persons 40–64 years old over the time span of 1999–2012.6 We therefore believed it was important to investigate PPI use and risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. The sample included individuals enrolled in the NIH-NIA supported Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs), a nationwide consortium of research sites in the United States. Subjects underwent detailed annual neuropsychological evaluations. We examined the risk associated with PPI use on incident MCI, dementia, and specifically Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Our second aim was to examine in a subgroup of persons with mild cognitive impairment at baseline whether PPI use conferred a higher risk of dementia and AD conversion in an already vulnerable group compared to persons with normal cognitive functioning. Analyses controlled for histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) medications (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and nizatidine) as these are an alternative treatment for gastric-acid related disorders. Boustani and colleagues7 found that H2RAs were a risk factor for incident cognitive impairment in a community residing sample of African Americans who were ≥65 years old. In contrast, PPIs were not associated with an increased risk. As prior studies did not control for H2RA medications, it was important to determine if they accounted for the conflicting findings.

METHODS

Participants

We used information in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database8 from 33 ADCs from September 2005 through September 2015. Written consent was obtained using forms approved by the institutional review boards at each site. Participants included persons with a baseline diagnosis of either ‘normal cognition’ or ‘mild cognitive impairment’ by their ADC clinicians. Clinical diagnosis at each Center relies on ADC coding guidelines using not only the performance on a core battery of neuropsychological tests9 but also the Clinical Dementia Rating10 score which provides an index of cognitive and functional status via a structured interview with the participant, a separate interview with the study informant, and a behavioral and neurological exam. A diagnosis of ‘normal cognition’ requires that neuropsychological test scores are within expectation for age and that persons are able to independently perform instrumental activities of daily living. A diagnosis of ‘MCI’ requires impairment in a single cognitive domain or multiple domains but also evidence of independence in performing activities of daily living.11

Criteria for inclusion of cognitively normal controls and MCI participants in the current study were information about PPI medication use at every visit, age ≥ 50 years old at baseline, and a consistent conversion diagnosis over time (e.g., conversion from normal cognition to MCI but then not back to normal cognition on the next visit).

PPI Medications

Participants were classified as PPI users vs. non-users at each annual visit, based on information on self- and informant-reported PPI medications. Theseincluded Omeprazole (Prilosec) and Omeprazole-sodium bicarbonate (Zegerid), esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex), and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant, Kapidex).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses included participants taking PPI medications at every visit, those taking PPI medications intermittently, vs. those never taking PPI medications. Multivariable Cox regression analyses using PROC PHREG were performed to evaluate the association between PPI use (always or intermittently vs. never) and a decline to MCI or dementia in the combined population of those either normal or MCI at baseline. Follow-up time was the time variable in the regression, beginning with the baseline visit. This was defined as the time to decline for those who did decline, and as the follow-up time for those who did not decline. In addition, a similar regression was run in which the outcome was a decline in cognitive status specifically to an underlying AD etiology (conversion to either MCI with suspected AD etiology or probable AD), in which MCI due to other suspected etiologies and non-AD dementias were treated as censored. Finally, separate regressions were run for persons with normal cognition at baseline versus those with MCI at baseline to determine whether one diagnostic group was more vulnerable to the adverse effects of PPIs on the risk of decline. Proportional hazard assumptions were tested via an interaction term between PPI use and follow-up time. No violation of the proportional hazard function was found for PPI. Statistical significance was set at p<.05, two-tailed.

All models controlled for potential confounders including demographic variables (age at baseline, race, gender, education), vascular comorbidities (self-reported hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke/transient ischemic attack), mood (depression), and anticholinergic and histamine-2 receptor antagonist medications. Information on vascular comorbidities and mood were taken from the NACC Uniform Data Set Subject Health History form which enquires about whether a person has a recent/active diagnosis in the past two years. Information about medications was taken from the NACC Uniform Data Set Subject Medications form which enquires about use of prescription and commonly prescribed over the counter medications within the two weeks before the current visit. The form lists 100 drugs most commonly reported by NACC participants. Additional drugs and their associated DrugIDs are available by accessing a website (https//alz.washington.edu/MEMBER/DrugCodeLookUp.html). In the current study, medications were classified into H2RAs (cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, and nizatidine)7 and those with moderate to severe anticholinergic effects.12

RESULTS

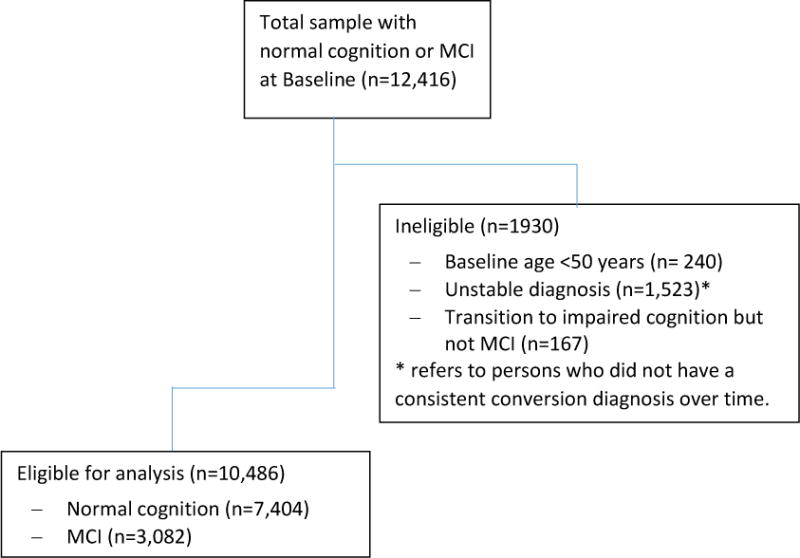

Figure 1 shows the number of participants initially reviewed for study inclusion. Of 12,416 potential individuals with baseline diagnoses of normal cognition and MCI, a total of 1,930 were excluded for reasons outlined in the Figure. Of the remaining 10,486 eligible participants, 884 (8.4%) reported always using PPIs, 1,925 (18.4%) reported intermittent use, and 7,677 (73.2%) reported never using PPIs at any annual follow-up.

Figure 1.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the always, intermittent, and never PPI users. A significantly higher percentage of never PPI users had achieved high school or above levels of education compared to those with intermittent PPI use. Always and intermittent PPI users were significantly older) than the never PPI users In addition, compared to the never PPI users, a significantly higher percentage of always and intermittent PPI users had heart disease, diabetes, hypertension, stroke/TIA, and depression, and a higher percentage of individuals in these latter groups took anticholinergic medications. All three groups differed from each other in the percentage of H2RA medication use (intermittent>always>never) and the number of follow-up visits (intermittent>never>always).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants by Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI) Use*

| Variable | Always PPI Users (n=884) |

Intermittent PPI Users (n=1,925) |

Never PPI Users (n=7,677) |

Overall p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) Age | 73.5 ± 8.9a | 73.7 ± 8.4b | 72.6 ± 9.4a,b | <0.001 |

| Female (n, %) | 522 (59.0) | 1168 (60.7) | 4756 (62.0) | 0.18 |

| African American (n, %) | 92 (11.1) | 249 (13.7) | 971 (13.5) | 0.14 |

| High School or above (n, %) | 833 (94.4) | 1793 (93.4)a | 7318 (95.7)a | <0.001 |

| Heart disease (n, %) | 289 (32.8)a | 588 (30.8)b | 1801 (23.6)a,b | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 131 (14.8)a | 285 (14.9)b | 795 (10.4)a,b | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 543 (61.7)a | 1144 (59.6)b | 3646 (47.6)a,b | <0.001 |

| Depression (n, %) | 239 (27.1)a | 519 (27.0)b | 1586 (20.7)a,b | <0.001 |

| Stroke/TIA (n, %) | 84 (9.6)a | 190 (9.9)b | 520 (6.8)a,b | <0.001 |

| Histamine-2 Receptor Antagonist Use (n, %) | 106 (12.0)a | 440 (22.9)a | 651 (8.5)a | <0.001 |

| Anticholinergic Medication Use (n, %) | 212 (24.0)a | 491 (25.5)b | 1034 (13.5)a,b | <0. 001 |

| Number of Visits, Median (Interquartile Range) | 3.0 (2.0 - 4.0)a | 5.0 (3.0 - 7.0)a | 4.0 (2.0 - 6.0)a | <0.001 |

A common superscript indicates a significant difference between groups, p<0.05

Risk for Cognitive Decline and Alzheimer’s Disease

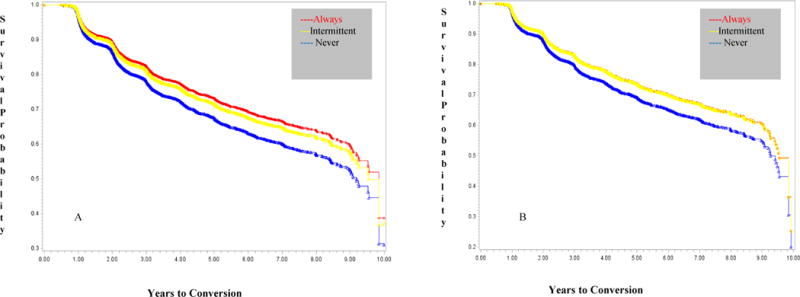

We first evaluated whether persons who did not have a dementia diagnosis at baseline were at an increased risk for conversion to a diagnosis of cognitive decline (transition from normal cognition to MCI or dementia; transition from MCI to dementia) as a function of PPI use. As seen in Table 2 (left side), the use of PPIs in the always user group was associated with a decreased risk of a decline in cognitive status (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.66–0.93, p=.005) after adjusting for potential confounders. Intermittent PPI use was also associated with a decreased risk of decline (HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.76–0.93, p<.001). The NACC database contains information concerning the suspected etiology for MCI or dementia, thus allowing us to examine if PPI use was associated with a risk for probable AD. PPI use in the always user group (Table 2, right side) was associated with a decreased risk of conversion to MCI or dementia due to AD (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.69–0.98, p=.026), as was intermittent use of PPIs (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.74–0.91, p<.001),after adjusting for potential confounders. Figure 2 shows the adjusted survival curves of cognitive decline to MCI or dementia (Panel A) and specifically to MCI or dementia due to suspected AD (Panel B). As seen, always PPI users had the highest survival rate, with intermittent users in the middle and never PPI users in the lowest group. The former groups both had higher and comparable rates of survival relative to the never PPI users for the transition to MCI or dementia due to AD.

Table 2.

Conversion of Baseline Normal Cognition to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Dementia and Conversion of Baseline MCI to Dementia

| Cognitive decline to MCI or Dementia due to any cause (n=10,486) | Cognitive decline to MCI or Dementia due to Alzheimer’s Disease (n=10,156) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Hazard ratio | p value | Hazard ratio | p value |

| Always proton pump inhibitor users vs. never users | 0.78 (0.66 - 0.93) | 0.005 | 0.819 (0.686 - 0.976) | 0.026 |

| Intermittent proton pump inhibitor users vs. never users | 0.84 (0.76 - 0.93) | 0.001 | 0.821 (0.738 - 0.914) | <0.001 |

| Histamine-2 receptor antagonist blocker user | 0.80 (0.70 - 0.90) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.65 - 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Anticholinergic medication user | 1.03 (0.93 - 1.14) | 0.57 | 0.97 (0.87 - 1.08) | 0.59 |

| Age at baseline | 1.04 (1.03 - 1.04) | <0.001 | 1.05 (1.04 - 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.64 (0.59 - 0.70) | <0.001 | 0.65 (0.60 - 0.71) | <0.001 |

| African American | 0.78 (0.68 - 0.89) | <0.004 | 0.79 (0.68 - 0.92) | 0.002 |

| High school or above at baseline | 0.78 (0.66 - 0.94) | 0.007 | 0.69 (0.58 - 0.83) | <0.001 |

| Heart disease at baseline | 1.09 (0.99 - 1.19) | 0.07 | 1.04 (0.94 - 1.14) | 0.44 |

| Diabetes at baseline | 1.18 (1.04 - 1.34) | 0.011 | 1.17 (1.02 - 1.34) | 0.026 |

| Hypertension at baseline | 1.01 (0.93 - 1.10) | 0.83 | 1.04 (0.96 - 1.14) | 0.34 |

| Depression at baseline | 2.66 (2.27 - 3.11) | <0.001 | 2.35 (2.14 - 2.58) | <0.001 |

| Stroke or TIA at baseline | 1.25 (1.10 - 1.43) | 0.001 | 1.22 (1.06 - 1.40) | 0.006 |

Figure 2.

Adjusted Survival Curves of Decline in Baseline Cognition to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Dementia (Panel A) and Decline in Baseline Cognition to MCI or Dementia Due to Suspected AD (Panel B)

Subgroup Analyses as a Function of Baseline Cognitive Status

A. Persons with Normal Cognition

Persons diagnosed with normal cognition at baseline (n=7,404, of whom 613 (8.3%) were always users, 1,351 (18.2%) were intermittent users, and 5,440 (73.5%) were never users) were examined separately to determine their relative risk for conversion to cognitive impairment (MCI or dementia) with vs. without AD etiology. Supplementary Table S1 shows the relative risk of conversion to MCI/dementia of any etiology (left side) and to an AD etiology (right side), controlling for potential confounders. PPI use in the always user group was associated with a decreased risk for the transition to MCI or dementia with any etiology (HR 0.73, 95% CI 0.55–0.97, p=.03), but was not a significant risk factor for an AD etiology (HR 0.74, CI 0.53–1.04, p=.08). Intermittent PPI use was not a significant risk factor for a decline in cognitive status due to any etiology (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.74–1.01, p=.07) or to an AD etiology (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.71–1.04, p=.13).

B. Persons with MCI

Of 3,082 persons with MCI at baseline, 271 (8.8%) were always PPI users, 574 (18.6%) were intermittent users, and 2,237 (72.6%) were never users. As seen in Supplementary Table S2 (left side), the relative risk for conversion to dementia of any etiology (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76–0.98, p=.03) and to an AD etiology (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73–0.94, p=.01) was significantly reduced in the intermittent PPI users, whereas there was no significant reduction in risk for dementia due to any etiology (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.67–1.02, p=.08) or an AD etiology (HR 0.97, 95% CI 0.79–1.19, p=.78) in those who always used PPIs.

Association Between Age and PPI Use

We restricted the sample to persons ≥ 75 years old because prior studies1,2,5 investigated the risk for cognitive decline only in persons in their 7th decade. The risk for cognitive decline in non-demented persons with normal cognition or MCI at baseline (n=4,562) was significantly reduced in intermittent PPI users (HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75–0.96, p=.009)), with a similar trend in always users) (HR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66–1.00, p=.049).

DISCUSSION

The results do not confirm reports1,2 that PPIs are linked to an increased risk of dementia and AD. Non-demented individuals at baseline who either always or intermittently took PPIs demonstrated a lower risk for cognitive decline compared to individuals who did not take PPIs. In addition, consistent and intermittent use was associated with a lower risk for decline due to a suspected AD etiology. When the sample was divided into those with either normal cognition or MCI, the same finding of a reduced risk was observed for both groups taking PPIs.

A strength of our study includes the well-phenotyped sample of individuals that receive diagnoses of cognitive status by a team of experienced clinicians in academic medical centers. ADC clinicians rely on a comprehensive neuropsychological battery and an independent interview with a study partner to obtain information about a person’s functional status. Two of the previous investigations1,2 in primary care patients relied on administrative databases using the diagnoses of a diverse group of practitioners presumably with varying degrees of experience in diagnosing dementia. Cognitive impairment and dementia are both underdiagnosed and underreported in primary care patients in the United States.13,14 Another strength is the availability of a broader age range of individuals, since prior studies only included persons in their 7th decade.1,2,5 We also controlled for H2RA use which was not previously done.1,2 Instead, these investigations included polypharmacy, defined as taking ≥5 drugs, as a covariate. This may or may not have included H2RAs which are an older class of drugs used to treat GI disorders. Boustani and colleagues7 found that H2RAs increased the risk for incident cognitive impairment more than two-fold in community residing African Americans, whereas there was no increased risk with PPIs. Failure of prior studies to control for H2RAs could have produced varying results depending on the mix of medications in the polypharmacy category. In our study, unlike Boustani et al., we found that H2RAs decreased the risk of MCI and dementia, including AD. Our sample was more heterogeneous in age and race which may have contributed to the differences in findings. Gray et al.15 more recently reported that H2RA use was not a risk factor for dementia or AD in participants in the Adult Changes in Thought (ACT) study. Strengths included the ability to evaluate exposure over a decade before enrollmen, and detailed information using pharmacy records that allowed them to examine dose-response relationships as risk factors.

Our findings replicate the results of a recent study by Booker and colleagues,5 but they conflict with two other reports1,2 demonstrating a detrimental influence of PPIs. The conflicting findings from the latter two reports cannot be attributed to differences in the classes of PPI medications that were used for analyses, as they were the same in our study. Information concerning dosage and schedule of PPI use was not available in the NACC database. This lack of dispensing data is also a limitation of other recent published reports.1,2,5 Another limitation concerns a reliance in our study on self-reports. This may have resulted in misclassification bias due to persons forgetting their medications, especially in those with MCI. This bias could have also occurred in the finding by Haenisch and collegues of detrimental associations of PPIs with cognition since they relied on interviews.2 All studies, including ours, lacked information on compliance with PPIs. Finally, in the analyses, we used all the available information and did not consider the missed visits. For example, a participant who was normal at baseline may have skipped a year 2 follow-up. If there were records of PPI use at all the available visits, we considered that person a PPI user at year 2. If the diagnosis was MCI at year-3, we would classify conversion at year 3 despite the missing of year 2 follow-up information. This could have led to misclassification of PPI use and/or time to diagnosis. Haenisch et al.2 used a last observation carried forward approach which could have led to similar misclassification.

Other risk factors for dementia and AD were replicated across all studies, involving older age, greater depression, and diabetes and stroke. As in all observational pharmacoepidemiological studies, biased by indication may be skewing these results to suggest that PPIs are not detrimental to cognition. In this analysis, we found that PPI users were at higher risk of dementia by their higher prevalence of CV disease, hypertension, diabetes, and depression. Hence, it is unlikely that our observation is related to a bias to prescribing PPIs to healthier individuals. It is possible that the PPI users, due to the greater frequency of cardiovascular risk factors, received better healthcare than non-PPI users. This, in turn, could have reduced their dementia risk.

Our findings do not support a detrimental impact of PPIs, despite mechanisms proposed as to why they should result in an increased risk for dementia. It has been hypothesized that PPIs are associated with increased beta amyloid which, in turn, is involved in the pathogenesis of AD. Badioloa and collegues16 observed increased beta amyloid levels in an amyloid cell model and in mice after PPI treatment. A human clinical trial demonstrating changes in cognitive functioning as well as both cerebrospinal fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers of AD linked to PPI use would support these findings. Another potential mechanism involves the role of vitamin B12, given an association between PPIs and B12 deficiency.17 Certain PPI medications including lansoprazole and omeprazole have been found to cross the blood brain barrier, demonstrating that they directly impact the brain.18,19 Caution needs to be exercised on speculating about the impact of PPIs on brain functioning, however, until a randomized, prospective clinical trial elucidates the impact of PPIs on cognition.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1: Conversion of Baseline Normal Cognition to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Dementia

Supplementary Table S2: Conversion of Baseline Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) to Dementia

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Emory Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIH-NIA 5 P50 AG025688)

Funding/Support:

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: The authors have no disclosures.

Author Contributions: Dr. Goldstein had full access to all the data in this study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analyses.

Study concept and design: Goldstein, Steenland, Hajjar

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors

Drafting of the manuscript: Goldstein, Steenland

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Statistical analysis: Steenland, Zhao

References

- 1.Gomm W, Von Holt K, Thome F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: A pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurology. 2016;73(4):410–416. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haenisch B, von Holt K, Wiese B, et al. Risk of dementia in elderly patients with the use of proton pump inhibitors. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2015;265:419–428. doi: 10.1007/s00406-014-0554-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zaudig M, Hiller W. SIDAM – Strukturiertes Interview für die Diagnose einer Demenz vom Alzheimer Typ, der Multi-Infarkt-(oder vaskulären) Demenz und Demenzen anderer Ätiologie nach DSM-III-R, DSM-IV und ICD-10 (SIDAM-Handbuch) Huber, Bern. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuller LH. Do proton pump inhibitors increase the risk of dementia? JAMA Neurology. 2016;73(4):379–381. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.4931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Booker A, Jacob LE, Rapp M, Bohlken J, Kostev K. Risk factors for dementia diagnosis in German primary care practices. International Psychogeriatrics. 2016;28(7):1059–1065. doi: 10.1017/S1041610215002082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantor ED, Rehm CD, Haas JS, Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Trends in prescription drug use among adults in the United States from 1999–2012. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2015;314(17):1818–1830. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boustani M, Hall KS, Lane KA, et al. The association between cognition and histamine-2 receptor antagonists in African Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:1248–1253. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01270.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, van Belle G, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Database. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2004;18:270–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, et al. Mild cognitive impairment-beyond controversies, towards a consensus: Report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2004;256(3):240–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai X, Campbell N, Kahn B, Callahan C, Boustani M. Long-term anticholinergic use and the aging brain. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2013;9:377–385. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: Prevalence and contributing factors. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2009;23:306–314. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181a6bebc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCarten JR, Anderson P, Kuskowski MA, McPherson SE, Borson S, Dysken MW. Finding dementia in primary care: The results of a clinical demonstration project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2012;60:210–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray SL, Walker R, Dublin S, et al. Histamine-2 receptor antagonist use and incident dementia in an older cohort. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(2):251–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Badiola N, Alcalde V, Pujol A, et al. The proton-pump inhibitor lansoprazole enhances amyloid beta production. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lam JR, Schneider JL, Zhao W, Corley DA. Proton pump inhibitor and histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and vitamin B12 deficiency. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2013;310(22):2435–2442. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng FO, Ho YF, Hung LC, Chen CF, Tsai TH. Determination and pharmacokinetic profile of omeprazole in rat blood, brain, and bile by microdialysis and high-performance liquid chromatography. Journal of Chromatography. 2002;949(1–2):35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)01225-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojo LE, Alzate-Morales J, Saavedra IN, Davies P, Maccioni RB. Selective interaction of lansoprazole and astemizole with tau polymers: potential new clinical use in diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2010;19(2):573–589. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1: Conversion of Baseline Normal Cognition to Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) or Dementia

Supplementary Table S2: Conversion of Baseline Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) to Dementia