Abstract

We tested within-person effects of alcohol on sexual behavior among young adults in a longitudinal burst design (N=213, 6487 person-days) using data collected from a previously published parent study. We differentiated effects of alcohol on likelihood of sexual activity versus use of protection against STDs or pregnancy on intercourse occasions by testing a multilevel multinomial model with four outcomes (no sex, oral sex without intercourse, protected intercourse, and unprotected intercourse). At the within-person level, effects of alcohol were hypothesized to be conditional upon level of intoxication (i.e., curvilinear effect). We also tested effects of four between-person moderators: gender, typical length of relationship with sexual partners, and two facets of self-control (effortful control and reactivity). Consistent with our hypothesis, low-level intoxication was associated with increased likelihood of engaging in oral sex or protected intercourse (relative to no sex) but was not related to likelihood of unprotected intercourse. The effect of intoxication on unprotected versus protected intercourse was an accelerating curve, significantly increasing likelihood of unprotected intercourse at high levels of intoxication. Between-person factors moderated associations between intoxication and sexual behavior. Effects of intoxication on both protected and unprotected intercourse were diminished for individuals with more familiar sexual partners. Effortful control exhibited a protective effect, reducing the effects of intoxication on likelihood of unprotected intercourse. Hypothesized effects of reactivity were not supported. Intoxication was a stronger predictor of oral sex and protected intercourse (but not unprotected intercourse) for women relative to men. Results highlight the inherent complexities of the alcohol-sexual behavior nexus.

Keywords: alcohol, sexual risk, experience sampling method (ESM), ecological momentary assessment (EMA), self-control

In young adults, social events are centered on drinking at bars, parties, and other social gatherings (Clapp, Min, Shillington, Reed, & Ketchie Croff, 2008; Simons, Gaher, Oliver, Bush, & Palmer, 2005). Alcohol is widely considered a “social lubricant” (Battista, MacDonald, & Stewart, 2012; Monahan & Lannutti, 2000) and facilitator of sexual activity (Fielder & Carey, 2010). Experimental research indicates that alcohol may foster greater sexual arousal (George et al., 2009), which in turn may be expected to increase sexual behavior irrespective of risk. To date, much of the research on alcohol’s effects has focused on the likelihood of risky sex (e.g., condomless sex), and the experimental literature provides support for a causal link (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2016). Alcohol myopia theory posits that the pharmacological effect of alcohol acts to restrict attention to the most salient cues and affects behavior by resolving inhibition conflict between impelling and inhibitory cues (Steele & Josephs, 1990). In respect to sexual behavior, sexual approach cues are often most salient, especially during heightened arousal, whereas concerns about potential negative consequences (e.g., health risks, pregnancy) are more distal and require accessing long-term memory (Maisto & Simons, 2016). Therefore, alcohol is thought to contribute to sexual risk behavior by impairing the ability to attend to distal inhibitory cues, resulting in behavior that is governed by the salient sexual approach cues (Davis, Hendershot, George, Norris, & Heiman, 2007; MacDonald, MacDonald, Zanna, & Fong, 2000). Although the myopia model is consistent with the observed experimental data, there is limited data on the purported cognitive mediators (Maisto, Palfai, Vanable, Heath, & Woolf-King, 2012; Maisto & Simons, 2016), and there are other potential theoretical mechanisms. For example, intoxication may act to increase the effects of implicit cognition on behavior (Hofmann & Friese, 2008; Simons, Maisto, Wray, & Emery, 2015; Wiers, Beckers, Houben, & Hofmann, 2009). In addition, research using event-level methods suggests complex associations between alcohol and sexual behavior in the natural environment (Patrick, Maggs, & Lefkowitz, 2015; Schroder, Johnson, & Wiebe, 2009; Scott-Sheldon, Carey, & Carey, 2010).

For example, Hensel and colleagues (2010) found no association between either alcohol or marijuana use and condom use in a sample of adolescent females ages 14–17. Similarly, Scott-Sheldon and colleagues (2010) did not find a main effect of alcohol consumption on condom use in a college student sample. Patrick and colleagues (2015) found significant effects of alcohol consumption and several sexual outcomes (e.g., oral sex, intercourse) but did not test effects on condom use. In contrast, Neal and Fromme (2007) found event-level effects of intoxication were specific to risky sex. Finally, in a study of “hook ups”, Lewis and colleagues (2012) found global but not event-level associations between alcohol consumption and likelihood of oral sex or vaginal intercourse and found no associations between alcohol consumption and condom use. The variation in findings across studies suggests that the effects of alcohol on sexual behavior change as a function of key moderators (Cooper, 2010; Weinhardt & Carey, 2000).

Moderators of associations between alcohol and sexual behavior

Effortful control and reactivity

Dual-process models of self-control posit two competing systems underlying self-regulation (Lieberman, 2007; Wiers et al., 2007; Wills et al., 2013). The effortful or reflective system is conceptualized as more deliberate and slower acting (Lieberman, 2007; Wiers et al., 2007) whereas the reactive or impulsive system is posited to be fast acting and relying more on heuristics, conditioned response patterns, and emotional reactions (Lieberman, 2007; Wiers et al., 2007). These domains have been variously labeled controlled and automatic; reflective and impulsive; c-system and x-system, cool and hot; good control and poor regulation; or self-regulation and reactivity (Hofmann, Friese, & Strack, 2009; Lieberman, 2007; Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999; Rothbart & Sheese, 2007; Wiers et al., 2007; Wills et al., 2013). Research indicates that reactivity, impulsivity and related constructs exhibit positive associations with alcohol use and risky sex (Hahn, Simons, & Simons, 2016; Simons, Carey, & Wills, 2009; Zapolski, Cyders, & Smith, 2009). In contrast, effortful control constructs exhibit inverse associations with substance use and risky sex (Simons, Maisto, & Wray, 2010; Wills et al., 2013).

Effortful control and reactivity-related constructs may buffer or potentiate, respectively, effects of intoxication and other risk factors on maladaptive outcomes (Farris, Ostafin, & Palfai, 2010; Simons et al., 2005; Wills, Ainette, Stoolmiller, Gibbons, & Shinar, 2008). For example, Abbey and colleagues (2006) found that executive cognitive functioning acted as a buffer, reducing the effects of intoxication on unprotected sex intentions in an alcohol administration study. Grenard and colleagues (2013) found that working memory was inversely related to associations between implicit risky sex associations and sexual risk behavior in a cross-sectional design. However, the hypothesis of moderating effects of reactivity on sexual risk outcomes has received less support (Simons et al., 2010; Walsh, Fielder, Carey, & Carey, 2014). Few studies that have tested effects of effortful control and reactivity on within-person associations between intoxication and sexual outcomes have used experience sampling methods. Experience sampling studies that test person × situation interactions integrate the person-level variables studied in global association studies and the event-level analysis of controlled experiments and can further advance understanding of the alcohol-sexual behavior nexus.

Gender

Gender differences in hazardous alcohol use and sexual behavior have decreased in recent years (Dawson, Goldstein, Saha, & Grant, 2015; Keyes, Martins, Blanco, & Hasin, 2010; Petersen & Hyde, 2010, 2011). Nonetheless, men tend to exhibit higher rates of hazardous alcohol use and sexual risk behaviors (Dawson et al., 2015; Petersen & Hyde, 2010), and gender remains a potentially important moderator of associations between alcohol and sexual behavior. One perspective is that men view more positive, instigating cues in sexual situations and hence alcohol exhibits more positive effects on sexual risk behavior for men relative to women (Cooper & Orcutt, 1997; O’Hara & Cooper, 2015).

In contrast, some research has indicated stronger effects of alcohol use on sexual behavior for women, though the pattern varies as a function of partner type and outcome (Kiene, Barta, Tennen, & Armeli, 2009; Owen, Fincham, & Moore, 2011; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010). For example, Owen and colleagues (2011) found stronger longitudinal effects of alcohol on casual sexual encounters for women. This pattern may be due to women having less permissive attitudes towards, more anxiety about, and lower engagement in, sexual behavior (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). Intoxication may serve to shift women’s focus, more toward immediate benefits (e.g., sexual satisfaction) and away from distal concerns (e.g., social mores, long-term mating strategies; Petersen & Hyde, 2010, 2011). Findings on the moderating effects of gender on associations between alcohol and condom use have been mixed. Kiene and colleagues (2009) found drinking in women increased the likelihood of unprotected sex with a casual partner but exhibited the opposite pattern with steady partners. In contrast, Scott-Sheldon and colleagues (2010) reported a positive effect of alcohol on unprotected sex only for women in the context of an established relationship, and others have found no evidence of differential gender effects (Corbin & Fromme, 2002). We add to the literature by testing effects of gender on within-person (i.e., daily) associations between intoxication level and several sexual outcomes (oral sex, protected/unprotected intercourse) to differentiate effects on engaging in sexual behavior relative to use of protection against STDs and pregnancy.

Partner relationship status

Cooper (2010) identified relationship as an important contextual factor that may have conflicting effects on sexual risk behavior. On the one hand, individuals seem to recognize the risk posed by a non-established partner and hence are more likely to use condoms with new or casual partners (LaBrie, Earleywine, Schiffman, Pedersen, & Marriot, 2005; Macaluso, Demand, Artz, & Hook, 2000; Walsh et al., 2014). Conversely, risk promoting factors such as impulsivity exhibit the strongest effects in first sexual encounters and in the context of low relationship commitment (Cooper, 2010). Extending this to risk promoting situational factors, Patrick and colleagues (2015) showed that drinking exhibited stronger within-day associations with sexual behavior for individuals who were single rather than in casual or committed relationships. Research on the effects of relationship on within-person associations between drinking and unprotected sex has produced mixed findings. For example, alcohol increases the likelihood of unprotected sex with casual partners but not in the context of more established relationships (Brown & Vanable, 2007; Kiene et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2005). However, there is also support for the converse. Scott-Sheldon and colleagues (2010) found that, for women, alcohol has inverse effects on condom use only with more established partners. The LaBrie study (2005) did not find an effect of alcohol use on condom use with either “new” partners or “established” partners. That is, alcohol decreased condom use only among “casual” partners. Finally, there are also null effects. For example, in a sample of young-adult women, Walsh and colleagues (2014) found that condom use varied as a function of partner relationship, but partner relationship did not moderate the effects of alcohol consumption on condom use as expected. We aim to extend these findings to examine moderating effects of partner relationships on daily associations between intoxication and multiple sexual outcomes.

Level of intoxication

Although college students tend toward higher consumption per drinking episode than their peers not in college (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2016b), the typical number of drinks per drinking day is relatively low. For example, the median number of drinks per drinking day among college students in the 2015 NSDUH was 3 (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2016a), a level unlikely to have substantial behavioral effects. The proportion of low-level drinking days may downwardly bias estimates of the effect of intoxication on risky sexual behavior (Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, & Schum, 2004; Maisto, Carey, Carey, Gordon, Schum, et al., 2004). Previous event-level research has mixed findings. Studies show a positive relationship between drinking and the likelihood of unprotected sexual intercourse with casual partners (Kiene et al., 2009; LaBrie et al., 2005). However, other research shows null effects of intoxication on unprotected intercourse (Howells & Orcutt, 2014; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010; Walsh et al., 2014). Walsh and colleagues (2014) found that the likelihood of condom use did not vary across non-drinking, drinking, or heavy episodic drinking events. However, within drinking events there was a negative association between number of drinks and condom use. This suggests that indicators of “drinking” or even of drinking 4 or more drinks are insufficient to adequately model the effects of intoxication on condom use. In addition, some research suggests alcohol use may increase use of condoms with casual partners (Kiene & Subramanian, 2013; Leigh et al., 2008). Hence, we propose to test nonlinear effects of intoxication on sexual behavior that may account for both positive and negative effects of intoxication and test whether negative effects of intoxication on protected intercourse occur primarily at high levels.

Current study

The current study was designed to address several gaps in the literature regarding associations between alcohol and sexual behavior in the natural environment. First, we test associations between alcohol and four outcomes (no sex - no oral sex or intercourse, oral sex but no intercourse, protected intercourse, and unprotected intercourse). This design enables the study to distinguish predictors of sexual activity from use of protection against STDs and pregnancy. Related to this, we test curvilinear effects of intoxication. Alcohol, socialization, and dating are tightly integrated among young adult college students. Hence, alcohol consumption was hypothesized to co-occur with sexual opportunities. However, low-level alcohol intoxication does not cause substantial impairment in judgment and decision-making. We hypothesized therefore that effects of alcohol on sexual risk are non-linear, exhibiting the most pronounced negative effects at higher, less frequent, levels of intoxication.

A second emphasis was to analyze person-level moderators. We hypothesized that effortful control buffers effects of intoxication on sexual behavior. In contrast, reactivity was hypothesized to predict stronger within-person associations between intoxication and sexual risk outcomes. We also examined partner relationships as a person-level factor. We treated this construct as a between-person variable in order to assess effects across each outcome (e.g., likelihood of no sex vs. protected intercourse, etc.). Here, we propose that alcohol intoxication has a stronger effect on sexual behavior among individuals who tend to have newer relationships with their sexual partners (cf. Cooper, 2010; Kiene et al., 2009). Finally, we tested effects as a function of gender to evaluate whether intoxication has stronger effects on sexual behavior for women relative to men (Kiene et al., 2009; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010).

Method

Participants

Participants were 213 young adults who reported at least one instance of sexual activity during the experience sampling study. This is a subset of 274 young adults in the parent study (see Simons et al., 2014). Women comprised 57.75% of the sample. Participants ranged in age from 18–27 (M = 19.86, SD = 1.36; Median = 20, Mode = 19), 94% were white, 3% multiracial, and 3% other races. Three percent were Hispanic or Latino. The participants were a subset of sexually active participants in a sample of individuals whose data were analyzed and reported in four previous publications (Simons et al., 2016; Simons, Wills, Emery, & Marks, 2015; Simons, Wills, Emery, & Spelman, 2015; Simons et al., 2014).

Measures

Baseline

Effortful control

Effortful control was defined by three indicators: (1) A 7‐item measure of planfulness (Kendall & Williams, 1982), (2) 6‐item measure of problem solving (Wills et al., 2001), and a 10‐item goal setting scale (SSRQ; Neal & Carey, 2005). High scores indicate greater self‐control (α = .81). Previous research with this sample indicates these items and the reactivity items described next form a two-factor structure (Simons, Wills, Emery, & Spelman, 2015).

Reactivity

Reactivity was defined by four indicators: (1) 5 items from the Eysenck impulsivity scale (Eysenck, Pearson, Easting, & Allsopp, 1985), (2) a 7‐item motor impulsivity subscale (Patton, Stanford, & Barrett, 1995), (3) a 8 item attention impulsivity scale (Patton et al., 1995), and (4) a 6‐item measure of distractibility (Kendall & Williams, 1982). High scores indicate greater reactivity/disinhibition (α = .79). Previous research indicates that these and comparable scales form a two-factor structure and exhibit expected associations with substance use and other risk behaviors (Simons, Wills, Emery, & Spelman, 2015; Wills et al., 2013).

Experience sampling and daily measures

Alcohol intoxication

Alcohol intoxication assessed by random in situ assessments of number of drinks in past 30 minutes (0 – 6 or more), an estimate of BAC (Matthews & Miller, 1979) derived from next morning assessments of total number of drinks (0 – 25) and hours spent drinking (0‐18), and perceived intoxication assessed the next morning (1–7 scale). The standardized mean of the three variables (i.e., nightly drinks from random prompts, BAC estimate from morning assessments, and perceived intoxication from morning assessments) was the estimate of intoxication.

Sexual behavior

Sexual behavior was assessed in the retrospective morning assessments. The items assessed the occurrence of oral sex or intercourse, how well the partner was known (5‐point scale ranging from < 1 day to >6 months), and whether they had used protection from STDs and pregnancy. During the experience sampling training, protection from STDs and pregnancy was defined as either using a condom or, if in the context of an exclusive relationship in which the partner’s STD status was known (e.g., partners had been tested) using a condom or some other form of birth control (e.g., the pill). The outcome is a nominal indicator of no sexual activity (i.e., no oral sex or intercourse), oral sex only, protected intercourse, or unprotected intercourse).

Procedure

Undergraduates who drank at least moderately (i.e., ≥ 12 drinks/week for women and ≥ 16 drinks / week for men; (Sanchez-Craig, Wilkinson, & Davila, 1995) were invited to participate in the experience sampling (ESM) study. Invited participants provided informed consent for the study, completed a set of baseline questionnaires, and were then trained in the use of the PDA. Palm handhelds were programmed with PMAT software (Weiss, Beal, Lucy, & MacDermid, 2004), modified by Joel Swendsen and CNRS, France. The program was configured to prompt participants to complete brief ~2 minute assessments at random times within 2-hour blocks between 10:00 am and 12:00 midnight. In addition, participants completed a self-initiated assessment each morning shortly after waking, which included assessments of sexual behavior not likely to be captured by the random prompts. The longitudinal burst design was structured such that participants did the experience sampling in six measurement bursts over the course of three semesters. The first burst was two weeks long, and each of the remaining bursts was one-week duration. Additional detail is in Simons, Wills, and Neal (2014).

Analysis plan

We tested a multilevel multinomial regression analysis in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015) with the maximum likelihood robust estimator. The outcome was a 4-category nominal variable reflecting sexual behavior each night (no sex (no oral sex or intercourse), oral sex (oral sex but not intercourse), protected intercourse, unprotected intercourse). We included participants who reported at least one instance of oral sex or intercourse. no sex was the comparison category. Six orthogonal day of the week indicators, elapsed days (days since beginning the study), and nighttime intoxication were Level 1 (daily level) predictors. Effortful control, reactivity, average partner relationship, gender, and university site were Level 2 (person level) predictors. We included a quadratic term for nighttime intoxication to test hypothesized curvilinear effects. Finally, cross-level interactions of effortful control, reactivity, partner relationship, and gender on the within-person intoxication effects were included to test hypothesized moderating effects. Continuous L1 predictors were centered at the person-mean and all L2 predictors were centered at the grand mean. Random variance in the elapsed day and intoxication slopes was evaluated. However, there was not evidence of substantial random slope variance and hence the slopes were treated as fixed effects. The outcomes had random intercepts, which were allowed to freely covary. Model diagnostics (e.g., log likelihood influence statistics, Cook’s D) indicated that six participants and an additional six daily observations had undue influence on the model and hence were removed prior to estimating the final model.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Compliance with the experience sampling protocol was good. Participants in the analysis sample provided an average of 31.34 (SD = 11.53) days of data over the course of three semesters (elapsed day M = 280.49, SD = 159.67, Mdn = 383 days). During the enrolled days, participants completed 79% of the random assessments and 95% of the morning assessments. The analysis sample consists of less than 95% of total study days due to attrition and/or technical problems (e.g., device failure). Participants reported having oral sex on 9.89% of days and vaginal or anal intercourse on 14.78% of days. Participants did not use protection from STDs or pregnancy on 47.24% of intercourse occasions. Participants reported drinking on 37.29 percent of study days. Table 1 contains summary statistics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| N | M | (SD) | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 207 (118W/89M) | ||||||

| Age | 207 | 19.87 | (1.36) | 18.00 | 27.00 | 1.46 | 7.73 |

| Partner relationships | 207 | 4.41 | (0.96) | 1.00 | 5.00 | −2.14 | 7.41 |

| Effortful control | 207 | 0.01 | (0.86) | −2.63 | 1.98 | −0.26 | 2.90 |

| Reactivity | 207 | −0.02 | (0.78) | −2.06 | 1.90 | 0.19 | 2.87 |

| Intoxication | 6487 | 0.00 | (0.87) | −0.53 | 4.94 | 2.00 | 6.72 |

Between-person correlations are presented in Table 2. Consistent with expectation, effortful control was inversely associated with degree of intoxication and positively associated with mean length of relationships with sexual partners. In contrast, reactivity was associated with greater degree of intoxication and marginally correlated with tending to know partners less (i.e., shorter average length of relationships with sexual partners; p = .06). Other associations between self-control traits and sexual behavior were not significant. Heavier drinkers reported having oral sex and intercourse on a higher proportion of days. However, drinking level was not associated with proportion of protected/unprotected intercourse. Sexual activity and use of protection were modestly inversely associated. Male gender was positively associated with drinking level, but was not associated with any of the sexual behavior variables.

Table 2.

Between-person correlations

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.00 | |||||||

| 2. University | .16* | 1.00 | ||||||

| 3. Effortful control | −.11 | −.09 | 1.00 | |||||

| 4. Reactivity | −.04 | −.04 | −.59*** | 1.00 | ||||

| 5. Intoxication | .16* | .07 | −.22** | .16* | 1.00 | |||

| 6. Partner relationship | −.11 | −.17* | .18* | −.13 | −.05 | 1.00 | ||

| 7. Oral sex | .03 | −.14* | −.05 | .10 | .19** | .16* | 1.00 | |

| 8. Intercourse | .01 | −.10 | −.13 | .09 | .25*** | .24*** | .69*** | 1.00 |

| 9. Protection | −.02 | .10 | .13 | −.09 | .00 | −.02 | −.16* | −.18* |

Note. N = 207, except for “Protection” which is the use of protection against STD’s / pregnancy during intercourse events (N =198). Intoxication, partner relationship, oral sex, intercourse, and protection are the person-means across days. In contrast to the analysis, Oral sex in this context refers to all instances of oral sex irrespective of engaging in intercourse.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Multilevel multinomial regression analysis

We tested the multilevel multinomial regression model described in the analysis plan. The analysis includes 6,487 days nested in 207 persons. In order to create a more parsimonious model, non-significant (p > .10) 3-way interactions (i.e., cross-level effects on the quadratic term) were iteratively dropped from the model. This resulted in retaining only the effortful control and reactivity effects on the intoxication quadratic term. The final model results are in Table 3. Table 4 presents a reparameterization of the model, to show effects on the contrast of protected vs. unprotected intercourse.

Table 3.

Multilevel Multinomial Regression – No sex reference category

| Outcome | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Oral Sex (n = 168) | Protected Intercourse (n = 506) | Unprotected Intercourse (n = 453) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE | p | RRR | B | SE | p | RRR | B | SE | p | RRR |

| Within-person | ||||||||||||

| Intoxication | 0.63 | 0.18 | <.001 | 1.87 | 0.52 | 0.11 | <.001 | 1.69 | 0.24 | 0.16 | .119 | 1.28 |

| Intoxication2 | −0.37 | 0.10 | <.001 | 0.69 | −0.25 | 0.05 | <.001 | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.07 | .854 | 0.99 |

| Cross-level (Person × Situation) | ||||||||||||

| Gender × Intox | −0.54 | 0.26 | .041 | 0.58 | −0.37 | 0.13 | .006 | 0.69 | −0.05 | 0.15 | .743 | 0.95 |

| Partner rel × Intox | −0.17 | 0.13 | .187 | 0.84 | −0.38 | 0.06 | <.001 | 0.68 | −0.21 | 0.09 | .026 | 0.81 |

| Effortful cntrl × Intox | −0.40 | 0.28 | .148 | 0.67 | −0.22 | 0.16 | .167 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.17 | .994 | 1.00 |

| Reactivity × Intox | −0.47 | 0.28 | .086 | 0.62 | −0.23 | 0.16 | .135 | 0.79 | −0.02 | 0.20 | .943 | 0.99 |

| Effortful cntrl × Intox2 | 0.16 | 0.14 | .248 | 1.17 | 0.20 | 0.09 | .021 | 1.22 | −0.09 | 0.09 | .310 | 0.92 |

| Reactivity × Intox2 | 0.12 | 0.14 | .415 | 1.12 | 0.15 | 0.08 | .055 | 1.17 | −0.05 | 0.10 | .595 | 0.95 |

| Between-person | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.34 | 0.23 | .148 | 0.15 | 0.20 | .438 | 0.25 | 0.26 | .333 | |||

| Partner relationships | 0.10 | 0.12 | .408 | 0.38 | 0.11 | .001 | 0.45 | 0.13 | <.001 | |||

| Effortful cntrl | 0.15 | 0.20 | .442 | −0.07 | 0.16 | .690 | −0.31 | 0.20 | .131 | |||

| Reactivity | 0.23 | 0.19 | .236 | 0.00 | 0.17 | .992 | 0.10 | 0.19 | .604 | |||

Note. N (days) = 6487, N (persons) = 207. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) = 7582.70, Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) = 8050.35. Gender is coded 0= women, 1 = men. Day of the week, elapsed day, and site are included as covariates but not depicted due to space limitations. Intox = Intoxication, Rel = Relationship, cntrl = control, RRR= relative risk ratio. Categories are mutually exclusive. The oral sex category refers to nights that oral sex but no intercourse occurred.

Table 4.

Multilevel Multinomial Regression – Unprotected intercourse reference category

| Outcome | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Oral Sex (n = 168) | Protected Intercourse (n = 506) | No Sex (n = 5360) | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Variable | B | SE | p | RRR | B | SE | p | RRR | B | SE | p | RRR |

| Within-person | ||||||||||||

| Intoxication | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.084 | 1.47 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.110 | 1.32 | −0.24 | 0.16 | 0.119 | 0.79 |

| Intoxication2 | −0.35 | 0.13 | 0.005 | 0.70 | −0.23 | 0.09 | 0.006 | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.855 | 1.01 |

| Cross-level (Person × Situation) | ||||||||||||

| Gender × Intox | −0.49 | 0.27 | 0.064 | 0.61 | −0.32 | 0.17 | 0.062 | 0.73 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.743 | 1.05 |

| Partner rel × Intox | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.778 | 1.04 | −0.17 | 0.10 | 0.091 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.026 | 1.23 |

| Effortful cntrl × Intox | −0.40 | 0.29 | 0.165 | 0.67 | −0.22 | 0.21 | 0.297 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.994 | 1.00 |

| Reactivity × Intox | −0.46 | 0.31 | 0.132 | 0.63 | −0.22 | 0.22 | 0.310 | 0.80 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.941 | 1.02 |

| Effortful cntrl × Intox2 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.120 | 1.29 | 0.29 | 0.13 | 0.020 | 1.34 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.309 | 1.09 |

| Reactivity × Intox2 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.339 | 1.18 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.097 | 1.23 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.597 | 1.05 |

| Between-person | ||||||||||||

| Gender | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.784 | −0.10 | 0.35 | 0.786 | −0.25 | 0.26 | 0.333 | |||

| Partner relationships | −0.35 | 0.16 | 0.031 | −0.08 | 0.16 | 0.640 | −0.45 | 0.13 | 0.000 | |||

| Effortful cntrl | 0.45 | 0.25 | 0.073 | 0.24 | 0.30 | 0.419 | 0.31 | 0.20 | 0.131 | |||

| Reactivity | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.596 | −0.10 | 0.29 | 0.725 | −0.10 | 0.19 | 0.606 | |||

Note. N (days) = 6487, N (persons) = 207, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) = 7582.70, Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) = 8050.35. Gender is coded 0= women, 1 = men. Day of the week, elapsed day, and site are included as covariates but not depicted due to space limitations. Intox = Intoxication, Rel = Relationship, cntrl = control, RRR= relative risk ratio.

Categories are mutually exclusive. The oral sex category refers to nights that oral sex but no intercourse occurred.

As shown in Table 3, there was a linear positive association between nighttime intoxication and the likelihood of oral sex or protected intercourse at mean levels of the L2 moderators. This effect represents the conditional effect of intoxication when the L2 moderators are 0 (i.e., at their mean) and at the person mean level of intoxication. However, the linear effect of intoxication on unprotected intercourse was not significant. Hence, at mean level of intoxication and mean levels of the L2 covariates, intoxication was associated with increased sexual activity but was not associated with an increase in sexual risk behavior relative to the no sex reference category. However, the significant quadratic effects and cross-level interactions indicate that this basic pattern varied as a function of intoxication level and individual difference factors.

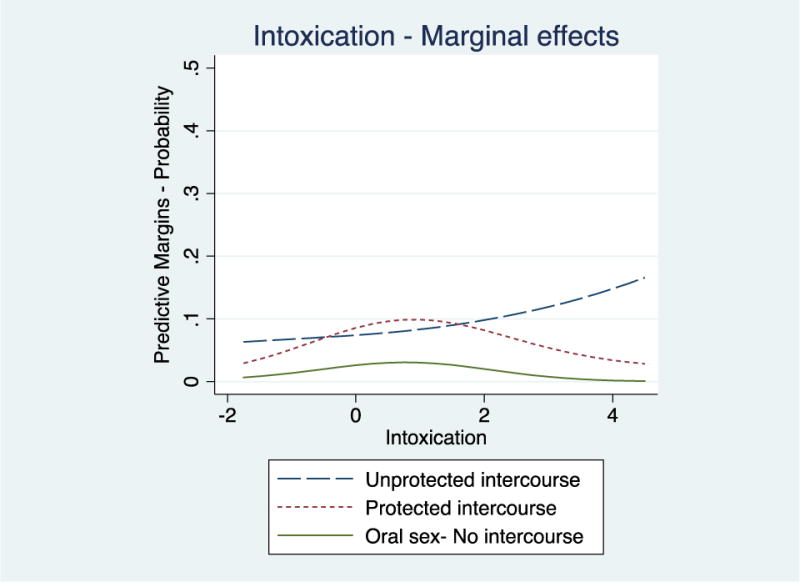

Intoxication level

The significant positive linear and negative quadratic effects on likelihood of both the oral sex and protected intercourse relative to the no sex comparison category indicate an inverted U function. Low levels of intoxication are associated with an increased likelihood of oral sex or protected intercourse (relative to no sex) followed by an inverse effect at approximately the person-centered intoxication level of 0.85 for oral sex and 1.05 for likelihood of protected intercourse. In contrast, as shown in Table 4 intoxication has no effect at mean levels on the likelihood of protected vs. unprotected intercourse, however, the effect becomes increasingly strong as intoxication increases (i.e., an accelerating curve for likelihood of unprotected intercourse; see Figure 1). For example, the relative risk of using protection when having intercourse decreases by a factor of 0.63 for every unit increase in intoxication level. The instantaneous slope of intoxication at the M +1 SD on likelihood of using protection is b = −0.49, p = .004. Hence, the pattern is consistent with the hypothesized mechanism whereby low-level intoxication is associated with increases in sexual activity but not increases in sexual risk. However, high levels of intoxication have a specific effect on the likelihood of using protection given engaging in intercourse.

Figure 1.

Average marginal effects of nighttime intoxication on sexual activity

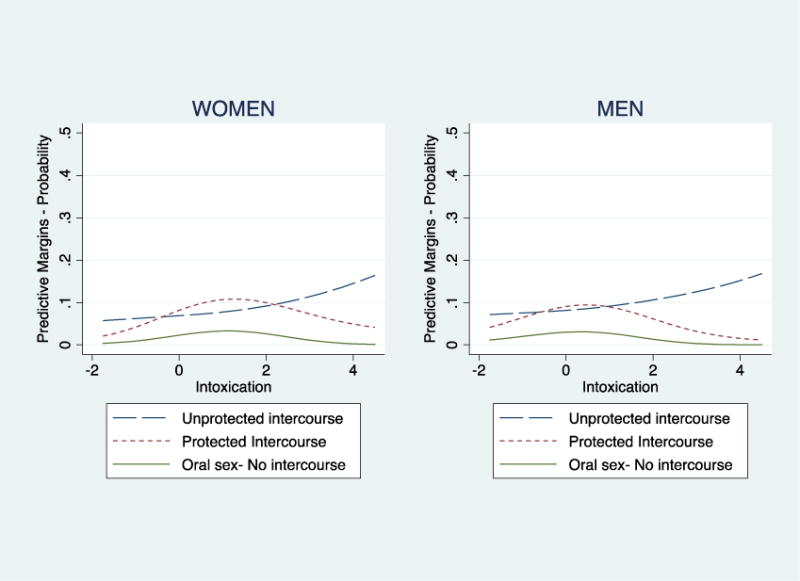

Gender effects

As shown in Table 3, the linear effect of intoxication on the likelihood of engaging in oral sex or protected intercourse (vs. no sex) was stronger for women relative to men. The respective relative risk ratios indicate that the effect of intoxication on likelihood of oral sex for men was 0.58 times the effect for women. Similarly, the effect of intoxication on likelihood of protected intercourse (versus no sex) was 0.69 times that of women. The effect of intoxication on unprotected intercourse vs. no sex did not differ as a function of gender. Similarly, the effect of intoxication on unprotected vs. protected intercourse did not vary as a function of gender (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Moderating effects of gender on daily associations between intoxication and sexual activity.

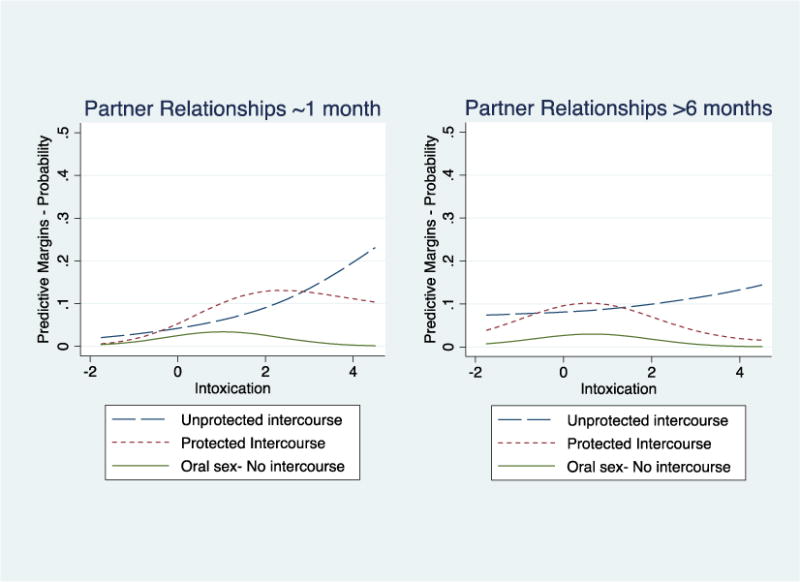

Partner relationship effects

Partner relationship did not moderate the effect of intoxication on oral versus no sex. However, participants who knew their sexual partners for a longer time exhibited a weaker association between intoxication and the likelihood of both protected and unprotected intercourse (relative to no sex). The relative risk ratio indicates that for every unit increase in partner relationship, the linear intoxication effect on protected intercourse versus no sex decreases by a factor of 0.68 and the effect on unprotected intercourse versus no sex decreases by a factor of 0.81. Although estimated at the between-subjects level, this is consistent with expectation that intoxication is more related to sexual behavior between partners who have not yet established sexual routines. In addition, Table 4 indicates a nonsignificant partner relationship by intoxication interaction predicting protected vs. unprotected intercourse. However, we note that the statistical significance of interactions in non-linear models pose interpretative challenges (Ai & Norton, 2003; Buis, 2010), and that the pattern of the effects (see Figure 3) is partially consistent with our hypothesis. There is a steeper increase in the likelihood of unprotected intercourse among participants with less familiar partners. Conversely, however, the likelihood of protected intercourse, declines more rapidly as a function of higher degrees of intoxication among individuals with more familiar partners. The relative risk ratio indicates that for every unit increase in partner relationship, the linear intoxication effect on protected versus unprotected intercourse decreases by a factor of 0.84.

Figure 3.

Moderating effects of partner relationships on daily associations between intoxication and sexual activity.

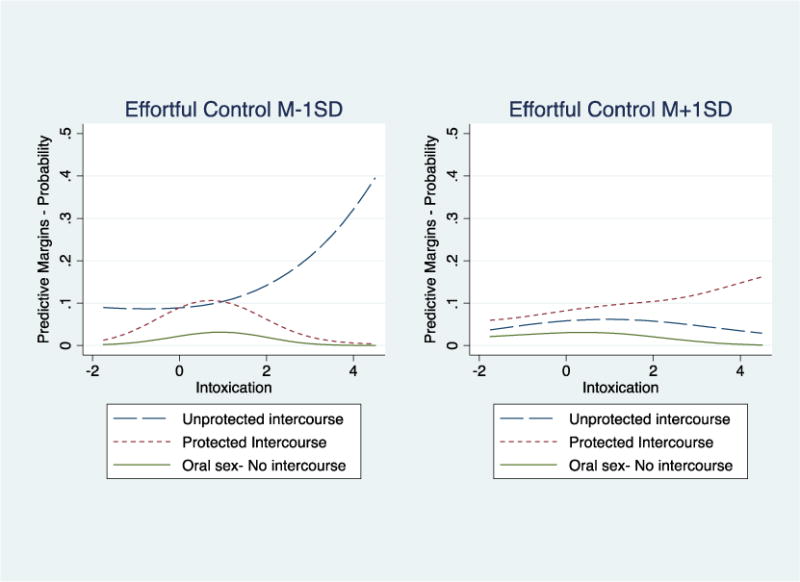

Effortful control and reactivity effects

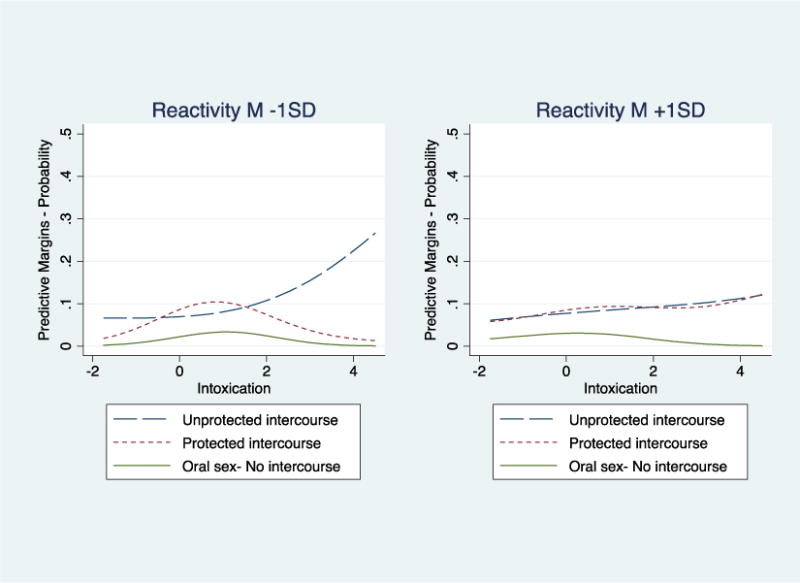

Consistent with expectation, effortful control was associated with an increased positive effect of intoxication on likelihood of protected intercourse (vs. no sex; see Table 3) and an increased likelihood of protected intercourse (vs. unprotected intercourse; see Table 4). Figure 4 depicts the marginal effects. At low levels of effortful control (M − 1 SD), intoxication was associated with an increased likelihood of protected intercourse (relative to no sex) up to approximately 0.69 SD above the intoxication mean, after which intoxication was inversely associated with likelihood of protected intercourse. This was accompanied by a steady increase in likelihood of unprotected intercourse. In contrast, for those with higher levels of effortful control, the probability of protected intercourse did not decline at higher levels of intoxication. Notably, effortful control did not moderate the relation between degree of intoxication and the likelihood of oral sex vs. no sex. Reactivity also showed marginal interaction effects (see Tables 3 and 4). However, contrary to hypotheses, the pattern depicted in Figure 5 is inconsistent with a risk promoting effect of reactivity.

Figure 4.

Moderating effects of effortful control on daily associations between intoxication and sexual activity.

Figure 5.

Moderating effects of reactivity on daily associations between intoxication and sexual activity.

Between-person effects

Between person effects must be considered within the context of the above cross-level interactions (e.g., interaction between effortful control and intoxication on unprotected intercourse, interaction between gender and intoxication on protected intercourse). That is, effects of between person variables may vary across situational context (i.e., level of intoxication). However, on average, sexual behavior did not vary as a function of gender, university, or self-control. Partner relationship did predict increased likelihood of both protected and unprotected sex. Hence, individuals who have more established partners tended to be more sexually active, and have intercourse more often, both protected and unprotected.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypotheses, the results of this study provide evidence for nonlinear effects of alcohol intoxication on sexual behavior. The cross-level interactions indicate variability in these effects as a function of individual difference factors. However, the average marginal effects (see Figure 1) indicate the following pattern. At lower intoxication levels (e.g., up to approximately 1 SD above the person-mean), drinking was associated with increases in likelihood of oral sex or protected intercourse relative to no sex. Intoxication did not increase the likelihood of unprotected intercourse (vs. no sex). Furthermore, at mean levels, intoxication did not increase the likelihood of using protection during intercourse. However, as intoxication increased, the likelihood of using protection when having intercourse decreased exponentially and showed a significant inverse relation with the likelihood of both oral sex and protected intercourse relative to unprotected intercourse at higher levels of intoxication. Behavioral effects of alcohol vary. At low doses, alcohol may result in mood elevation and increased sociability (Peele & Brodsky, 2000). As blood alcohol concentration increases toward 0.08 g/dl, alcohol impairments in executive functioning are more pronounced (Lane, Cherek, Pietras, & Tcheremissine, 2004; Weafer & Fillmore, 2008). Hence, light drinking may be associated with increased sexual opportunity but is not associated with substantial increases in liability for unprotected intercourse. In contrast, heavy drinking can impair judgment and increases the likelihood of unprotected intercourse. Interpreted through the lens of the alcohol myopia model, only higher levels of intoxication interfere with an individual’s ability to process distal cues (e.g., risk of contracting an STD; Steele & Josephs, 1990). This finding may in part explain disparate findings in the literature. In samples with few heavy drinking events, the effects of alcohol on sexual risk behavior may not be observed.

Also as we predicted, our findings are consistent with evidence suggesting that alcohol has a stronger effect on sexual behavior, including unprotected intercourse, for individuals with less established partners (Kiene et al., 2009; Patrick et al., 2015). The multinomial model illustrated complex associations between intoxication and sexual behavior as a function of typical partner relationship. Effects of intoxication on likelihood of oral sex without intercourse did not vary as a function of partner relationship. In contrast, intoxication had stronger effects on the likelihood of both protected and unprotected intercourse vs. no sex for individuals who, on average, were less familiar with their partners. The significant effect on both protected and unprotected intercourse (relative to no sex) suggests that this may be a function of alcohol having less of an effect on sexual opportunity among more established partners. However, the relationship was complex, as higher level of intoxication was also associated with a steeper decline in using protection during intercourse among those who knew partners for longer periods. In these cases, risk cues may be less salient, which would contribute to stronger effects of alcohol. Future research is warranted to further examine this question by testing event-level partner relationship effects.

Intoxication had stronger effects on oral sex or protected intercourse for women relative to men, yet had no effect on the likelihood of unprotected intercourse (relative to no sex). The pattern of results is consistent with the commonly held belief that young adult men want sex at every opportunity, and, therefore, relative to women level of intoxication is less of a factor. Indeed, though gender differences may be diminishing and more modest than typically thought, men have more permissive attitudes and more sexual partners than women (Petersen & Hyde, 2010). In contrast, men and women may share more similar concerns about the consequences of not using protection (cf. Corbin & Fromme, 2002). However, this pattern is somewhat inconsistent with previous research that demonstrates stronger effects for women of intoxication on unprotected intercourse with casual partners (Kiene et al., 2009) or steady partners (Scott-Sheldon et al., 2010). This may be a function of our analysis not including the higher order relationship by gender interaction due to the already high degree of complexity.

As we hypothesized, effortful control acted as a protective factor attenuating the association between intoxication and unprotected intercourse. Therefore, effortful control appears to facilitate safer sex decisions when intoxicated. This pattern of results suggests that effects of effortful control are specific to modulating effects of alcohol on behaviors of greatest risk (i.e., unprotected intercourse) rather than lower risk behavior (i.e., oral sex). For individuals high in effortful control, there was a modest positive linear association between intoxication and the likelihood of protected intercourse. In contrast, for those low in effortful control, higher intoxication was associated with decreases in the likelihood of using protection and consequent increases in probability of unprotected intercourse. In addition, at the bivariate level, effortful control exhibited modest inverse associations with intoxication and positive associations with familiarity with sexual partners. Hence, the findings support multiple conceptualizations on the effects of effortful control.

First, effortful control may promote adaptive outcomes prospectively, by creating socio-environmental contexts that minimize risk (Hofmann, Baumeister, Förster, & Vohs, 2012; Wills, Simons, Sussman, & Knight, 2016). That is, individuals high in effortful control may be less likely to “find themselves” heavily intoxicated with an unfamiliar potential sexual partner. In addition, effortful control appears to facilitate safer sex decisions “in the moment” reducing the effects of intoxication. These two conceptualizations may be related in that effortful control may be associated with both a restricted range of intoxication as well as ability to control behavior within that range. The specific mechanisms underlying the cross-level effects are unclear. This may reflect effects of working memory on decision-making. For example, individuals high in working memory exhibit weaker associations between automatic approach cues and behavior, including sexual risk associations (Grenard et al., 2013; Hofmann, Gschwendner, Friese, Wiers, & Schmitt, 2008; van Hemel-Ruiter, de Jong, & Wiers, 2011). Interestingly, there is also evidence that working memory may enhance associations between safe-sex impact associations and behavior (Grenard et al., 2013). Further research is needed to examine effects of components of executive functioning in risk behavior.

Relative to effortful control, reactivity exhibited the opposite pattern of bivariate effects. However, the risk promoting cross-level effects were not supported in the multi-level model. In fact, the pattern of effects was not consistent with expectation. Individuals with low reactivity tended to exhibit stronger positive effects of intoxication on the probability of unprotected intercourse. It is possible that individuals high in reactivity are more familiar with higher levels of intoxication and “hooking up” (Fielder, Walsh, Carey, & Carey, 2013; Hahn et al., 2016; Olmstead, Pasley, & Fincham, 2013) and hence better prepared to protect themselves when the event occurs. More reactive individuals may be more familiar with engaging in sexual behavior when intoxicated and thus have established routines. Alternatively, related qualities of extraversion may facilitate safe sex negotiations. Interpretations should be made with caution given the fact that this is a marginal effect after partialling out the effects of effortful control, gender, and partner relationship.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, sexual risk behaviors are low base rate outcomes. Although this research involved a moderate to heavy drinking participant sample, high-level intoxication events and sexual outcomes were relatively infrequent. As a result, confidence intervals for point estimates at high levels of intoxication were quite wide. Second, the partner relationship variable assessed the length of time the partner was known. When the duration is short, this provides a good indication that the extent of relationship is minimal. However, at the longer durations, partner relationships could be more heterogeneous, ranging from a long-term committed relationship to a partner that the individual may have met some time ago but still not know very well. In addition, hypotheses about the effects of this construct on the relationship between alcohol and sexual behavior are, in part, within-person effects. However, partner relationship at the event level can only be assessed given sexual behavior. Hence, testing event level effects of partner relationship requires restricting the analysis to sexual events. In the current study, we aimed to examine the effects of alcohol on the occurrence of sexual behavior and thus treated relationship status at the between-subject level (cf. Patrick et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the results showed that alcohol effects vary as a function of familiarity with sexual partners, which has variance both between- and within-persons. Third, the recruitment of a sample of relatively heavy drinking young adults facilitated testing hypotheses regarding within-person effects of alcohol on risk behavior. However, it also likely restricted the range of between-person differences. Indeed, in the current sample gender, effortful control, and reactivity were not significantly correlated with oral sex, intercourse, or use of protection at the between persons-level, though research suggests that there are significant correlations between both gender and self-control constructs and sexual behavior outcomes (Hahn et al., 2016; Nydegger, Ames, & Stacy, 2015; Simons et al., 2010). Finally, the study did not assess multiple forms of contraception. Predictors of condomless sex with a non-exclusive partner may vary depending on whether some form of birth control that does not protect from STDs (e.g., oral contraceptives) is being used. Similarly, there may be interesting differences in predictors of antecedent birth control (e.g., oral contraceptives) versus use of a condom, which is a decision that is being made in the heat of the moment.

Summary

Sexual behavior among young adults is complex and depends on a wide range of factors. Lower levels of intoxication were associated with an increased likelihood of oral sex and protected intercourse, whereas the likelihood of unprotected intercourse was increased only at higher levels of intoxication. Effects of intoxication on sexual behavior tended to be stronger for those who were less familiar with their partners. Effortful control exhibited a protective effect contributing to safer sex decisions. For the young adult looking for love, the stars align when having a few drinks with friends. Unfortunately, a few drinks too many, an attractive stranger, and poor planning can create the perfect storm.

Public Significance.

Nonlinear associations between alcohol and sexual outcomes may account for discrepant findings in the literature. Effortful control acts as a buffer, reducing associations between intoxication and unprotected intercourse.

Acknowledgments

none

Role of funding source

This research was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01AA017433 (JSS). The sample is a subset of a previously analyzed dataset (Simons, Emery, Simons, Wills, & Webb, 2016; Simons, Wills, Emery, & Marks, 2015; Simons, Wills, Emery, & Spelman, 2015; Simons, Wills, & Neal, 2014). These prior manuscripts address distinct topics not including sexual risk behavior, the topic of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Note: Jeffrey S. Simons, Department of Psychology, The University of South Dakota

Author Disclosures

Contributors

J. Simons designed the study, conducted analysis, and wrote first draft. R. Simons, S. Maisto, A. Hahn, and K. Walters contributed subsections and/or contributed to revising final draft. All authors approve the final article.

Conflict of interest

No conflict declared

References

- Abbey A, Saenz C, Buck PO, Parkhill MR, Hayman LW., Jr The effects of acute alcohol consumption, cognitive reserve, partner risk, and gender on sexual decision making. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(1):113–121. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics letters. 2003;80(1):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Battista SR, MacDonald D, Stewart SH. The effects of alcohol on safety behaviors in socially anxious individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2012;31(10):1074–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buis M. Stata tip 87: Interpretation of interactions in non-linear models. The Stata Journal. 2010;10:305–308. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp JD, Min JW, Shillington AM, Reed MB, Ketchie Croff J. Person and environment predictors of blood alcohol concentrations: A Multi‐level study of college parties. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2008;32(1):100–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Toward a person × situation model of sexual risk-taking behaviors: illuminating the conditional effects of traits across sexual situations and relationship contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;98(2):319–341. doi: 10.1037/a0017785. doi:2010-00584-011[pii]10.1037/a0017785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Orcutt HK. Drinking and sexual experience on first dates among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(2):191–202. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Fromme K. Alcohol use and serial monogamy as risks for sexually transmitted diseases in young adults. Health Psychology. 2002;21(3):229–236. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KC, Hendershot CS, George WH, Norris J, Heiman JR. Alcohol’s effects on sexual decision making: an integration of alcohol myopia and individual differences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(6):843–851. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Grant BF. Changes in alcohol consumption: United states, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;148:56–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SB, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personality and Individual Differences. 1985;6(5):613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Farris SR, Ostafin BD, Palfai TP. Distractibility moderates the relation between automatic alcohol motivation and drinking behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(1):151–156. doi: 10.1037/a0018294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Predictors and consequences of sexual “hookups” among college students: a short-term prospective study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(5):1105–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Walsh JL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Predictors of sexual hookups: a theory-based, prospective study of first-year college women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42(8):1425–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Davis KC, Norris J, Heiman JR, Stoner SA, Schacht RL, Kajumulo KF. Indirect effects of acute alcohol intoxication on sexual risk-taking: The roles of subjective and physiological sexual arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(4):498–513. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenard JL, Ames SL, Stacy AW. Deliberative and spontaneous cognitive processes associated with HIV risk behavior. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2013;36(1):95–107. doi: 10.1007/s10865-012-9404-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn AM, Simons RM, Simons JS. Childhood Maltreatment and Sexual Risk Taking: The Mediating Role of Alexithymia. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2016;45(1):53–62. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0591-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensel DJ, Stupiansky NW, Orr DP, Fortenberry JD. Event-level marijuana use, alcohol use, and condom use among adolescent women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2010;38(3):239–243. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f422ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Baumeister RF, Förster G, Vohs KD. Everyday temptations: An experience sampling study of desire, conflict, and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2012;102(6):1318–1335. doi: 10.1037/a0026545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M. Impulses got the better of me: alcohol moderates the influence of implicit attitudes toward food cues on eating behavior. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(2):420–427. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Friese M, Strack F. Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009;4(2):162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Gschwendner T, Friese M, Wiers RW, Schmitt M. Working memory capacity and self-regulatory behavior: Toward an individual differences perspective on behavior determination by automatic versus controlled processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95(4):962–977. doi: 10.1037/a0012705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells NL, Orcutt HK. Diary study of sexual risk taking, alcohol use, and strategies for reducing negative affect in female college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75(3):399–403. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall PC, Williams CL. Assessing the cognitive and behavioral components of children’s self-management. In: Karoly P, Kanfer FH, editors. Self-management and behavior change. New York: Pergamon Press; 1982. pp. 240–284. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martins SS, Blanco C, Hasin DS. Telescoping and gender differences in alcohol dependence: New evidence from two national surveys. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):969–976. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Barta WD, Tennen H, Armeli S. Alcohol, helping young adults to have unprotected sex with casual partners: findings from a daily diary study of alcohol use and sexual behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;44(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Subramanian S. Event-level association between alcohol use and unprotected sex during last sex: evidence from population-based surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):583. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J, Earleywine M, Schiffman J, Pedersen E, Marriot C. Effects of alcohol, expectancies, and partner type on condom use in college males - event-level analyses. Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(3):259–266. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane SD, Cherek DR, Pietras CJ, Tcheremissine OV. Alcohol effects on human risk taking. Psychopharmacology. 2004;172(1):68–77. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Vanslyke JG, Hoppe MJ, Rainey DT, Morrison DM, Gillmore MR. Drinking and condom use: results from an event-based daily diary. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12(1):104–112. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9216-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Granato H, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Kilmer JR. Predictors of hooking up sexual behaviors and emotional reactions among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(5):1219–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MD. Social cognitive neuroscience: a review of core processes. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:259–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso M, Demand MJ, Artz LM, Hook WE. Partner type and condom use. AIDS. 2000;14:537–546. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003310-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald TK, MacDonald G, Zanna MP, Fong G. Alcohol, sexual arousal, and intentions to use condoms in young men: Applying alcohol myopia theory to risky sexual behavior. Health Psychology. 2000;19(3):290–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL. Effects of alcohol and expectancies on HIV-related risk perception and behavioral skills in heterosexual women. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2004;12(4):288–297. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.12.4.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Carey MP, Carey KB, Gordon CM, Schum JL, Lynch KG. The Relationship Between Alcohol and Individual Differences Variables on Attitudes and Behavioral Skills Relevant to Sexual Health Among Heterosexual Young Adult Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2004;33(6):571–584. doi: 10.1023/B:ASEB.0000044741.09127.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Palfai T, Vanable PA, Heath J, Woolf-King SE. The effects of alcohol and sexual arousal on determinants of sexual risk in men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41(4):971–986. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9846-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Simons JS. Research on the Effects of Alcohol and Sexual Arousal on Sexual Risk in Men who have Sex with Men: Implications for HIV Prevention Interventions. AIDS and behavior. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S158–172. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalfe J, Mischel W. A hot/cool-system analysis of delay of gratification: dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review. 1999;106(1):3–19. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan J, Lannutti PJ. Alcohol as social lubricant; alcohol myopia theory, social self-esteem, and social interaction. Human Communication Research. 2000;26(2):175–202. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Statistical Modeling Software: Release 7.4. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. A follow-up psychometric analysis of the self-regulation questionnaire. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19(4):414–422. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Fromme K. Event-level covariation of alcohol intoxication and behavioral risks during the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:294–306. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydegger LA, Ames SL, Stacy AW. The development of a new condom use expectancy scale for at-risk adults. Social Science and Medicine. 2015;143:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara RE, Cooper ML. Bidirectional associations between alcohol use and sexual risk-taking behavior from adolescence into young adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015;44(4):857–871. doi: 10.1007/s10508-015-0510-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead SB, Pasley K, Fincham FD. Hooking up and penetrative hookups: correlates that differentiate college men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42(4):573–583. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9907-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Fincham FD, Moore J. Short-term prospective study of hooking up among college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(2):331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Maggs JL, Lefkowitz ES. Daily associations between drinking and sex among college students: A longitudinal measurement burst design. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2015;25(2):377–386. doi: 10.1111/jora.12135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barrett ES. Factor structure of the Barrett impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peele S, Brodsky A. Exploring psychological benefits associated with moderate alcohol use: a necessary corrective to assessments of drinking outcomes? Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;60:221–247. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin. 2010;136(1):21–38. doi: 10.1037/a0017504. doi:10.1037/a0017504 10.1037/a0017504.supp (Supplemental) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen JL, Hyde JS. Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: A review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. Journal of Sex Research. 2011;48(2–3):149–165. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.551851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Sheese BE. Temperament and Emotional Regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Craig M, Wilkinson DA, Davila R. Empirically based guidelines for moderate drinking: 1-year results from three studies with problem drinkers. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(6):823–828. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.85.6.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder KE, Johnson CJ, Wiebe JS. An event-level analysis of condom use as a function of mood, alcohol use, and safer sex negotiations. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38(2):283–289. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Cunningham K, Johnson BT, Carey MP, Team, M. R. Alcohol Use Predicts Sexual Decision-Making: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Experimental Literature. AIDS and behavior. 2016;20(Suppl 1):S19–39. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1108-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP, Carey KB. Alcohol and risky sexual behavior among heavy drinking college students. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(4):845–853. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9426-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Carey KB, Wills TA. Alcohol abuse and dependence symptoms: A multidimensional model of common and specific etiology. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(3):415–427. doi: 10.1037/a0016003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Emery NN, Simons RM, Wills TA, Webb MK. Effects of alcohol, rumination, and gender on the time course of negative affect. Cogn Emot. 2016:1–14. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1226162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:459–469. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Maisto SA, Wray TB. Sexual risk-taking among young adult dual alcohol and marijuana users. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:533–536. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Maisto SA, Wray TB, Emery NN. Acute Effects of Intoxication and Arousal on Approach/Avoidance Biases Toward Sexual Risk Stimuli in Heterosexual Men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0477-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Emery NN, Marks RM. Quantifying alcohol consumption: Self-report, transdermal assessment, and prediction of dependence symptoms. Addictive Behaviors. 2015;50:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Emery NN, Spelman PJ. Keep calm and carry on: Maintaining self-control when intoxicated, upset, or depleted. Cogn Emot. 2015:1–15. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2015.1069733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Wills TA, Neal DJ. The many faces of affect: A multilevel model of drinking frequency/quantity and alcohol dependence symptoms among young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(3):676–694. doi: 10.1037/a0036926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45(8):921–933. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health - Public Data Files. 2016a [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2016b [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hemel-Ruiter ME, de Jong PJ, Wiers RW. Appetitive and regulatory processes in young adolescent drinkers. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(1–2):18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh JL, Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Do alcohol and marijuana use decrease the probability of condom use for college women? Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51(2):145–158. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.821442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Fillmore MT. Individual differences in acute alcohol impairment of inhibitory control predict ad libitum alcohol consumption. Psychopharmacology. 2008;201(3):315–324. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1284-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP. Does alcohol lead to sexual risk behavior? Findings from event-level research. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:125–157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss HM, Beal DJ, Lucy SL, MacDermid SM. Constructing EMA studies with PMAT: The Purdue momentary assessment tool user’s manual. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.mfri.purdue.edu/pages/PMAT/pmatusermanual.pdf.

- Wiers RW, Bartholow BD, van den Wildenberg E, Thush C, Engels RCME, Sher KJ, Stacy AW. Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: A review and a model. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2007;86(2):263–283. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Beckers L, Houben K, Hofmann W. A short fuse after alcohol: implicit power associations predict aggressiveness after alcohol consumption in young heavy drinkers with limited executive control. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior. 2009;93(3):300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.003. doi:S0091-3057(09)00069-0[pii] 10.1016/j.pbb.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Ainette MG, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Shinar O. Good self-control as a buffering agent for adolescent substance use: An investigation in early adolescence with time-varying covariates. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22(4):459–471. doi: 10.1037/a0012965. doi:2008-17215-001[pii] 10.1037/a0012965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Bantum EO, Pokhrel P, Maddock JE, Ainette MG, Morehouse E, Fenster B. A dual-process model of early substance use: tests in two diverse populations of adolescents. Health Psychology. 2013;32(5):533–542. doi: 10.1037/a0027634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Cleary S, Filer M, Shinar O, Mariani J, Spera K. Temperament related to early-onset substance use: test of a developmental model. Prevention Science. 2001;2(3):145–163. doi: 10.1023/a:1011558807062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Simons JS, Sussman S, Knight R. Emotional self-control and dysregulation: A dual-process analysis of pathways to externalizing/internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being in younger adolescents. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;163(Suppl 1):S37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapolski TC, Cyders MA, Smith GT. Positive urgency predicts illegal drug use and risky sexual behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):348–354. doi: 10.1037/a0014684. doi:2009-08896-018 [pii] 10.1037/a0014684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]