ABSTRACT

Many hip arthroscopy patients experience significant pain in the immediate postoperative period. Although peripheral nerve blocks have demonstrated efficacy in alleviating some of this pain, they come with significant costs. Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) may be a significantly cheaper and efficacious treatment modality. Although LIA has been well studied in hip and knee arthroplasty, its efficacy in hip arthroscopy is unclear. The purpose of this retrospective study is to determine the efficacy of a single extracapsular injection of bupivacaine–epinephrine during hip arthroscopy in reducing the rate of elective postoperative femoral nerve blocks. A retrospective review of 100 consecutive patients who underwent primary hip arthroscopy at a single medical center was performed. The control group consisted of 50 patients before the implementation of the current LIA protocol, whereas another 50 patients received a 20-ml extracapsular injection of 0.25% bupivacaine–epinephrine under direct arthroscopic visualization after capsular closure. In the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU), patients were offered a femoral nerve block for uncontrolled pain. The rate of femoral nerve block, and total opioid consumption, was compared between groups. The proportion of patients receiving elective femoral nerve blocks was significantly less in the LIA group (34%) as compared with the control group (56%; P = 0.027). There was no significant difference in total PACU opioid consumption between groups (P = 0.740). The decreased utilization of postoperative nerve blocks observed in the LIA group suggests that LIA may improve postoperative pain management and should be considered as a potentially cost-effective tool in pain management in hip arthroscopy patients.

Level of Evidence: III

INTRODUCTION

As the number of hip arthroscopy procedures in the United States continues to increase at a dramatic rate [1, 2] with expanding indications [3], there is growing interest in the improvement of postoperative pain management in these patients. Unfortunately, many patients experience significant pain in the immediate postoperative period, with several studies demonstrating moderate to severe pain in up to 90% of hip arthroscopy patients immediately following surgery [4, 5].

Postoperative pain management plays a central role in the quality of recovery, as even short intervals of acute pain have been shown to precipitate chronic pain, psychological distress and increased neuronal sensitization [6]. These effects are obviously counterproductive in the expeditious recovery and rehabilitation of surgical patients. Furthermore, higher postoperative pain scores are associated with prolonged hospital stays and readmissions [7, 8]. Despite the well-known importance of postoperative pain management, there is little consensus regarding the best pain management strategy for hip arthroscopy patients.

One of the more common pain management modalities for hip arthroscopy is a peripheral nerve block in the perioperative period. Both femoral nerve blocks and fascia iliaca blockades, given either pre- or postoperatively, have demonstrated efficacy in decreasing pain and opioid use in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) following hip arthroscopy [4, 5, 9]. However, peripheral nerve blocks are not without significant cost, as they require equipment costs, ultrasound procedural fees and potentially professional fees from an anesthesiologist. Although rare, regional nerve blocks also carry the risk of paresthesias, permanent nerve damage and postoperative falls [10–13].

Consequently, there has been a growing interest among orthopaedic surgeons regarding local infiltration analgesia (LIA) as a pain management modality for a variety of orthopaedic procedures [14–23]. Several studies have focused on the role of LIA in the setting of total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty [24–26], where LIA has been shown to decrease pain and opioid consumption [27, 28]. There have been several studies which suggest a beneficial role of LIA in hip arthroscopy patients, though they have mostly focused on comparing different methods of LIA, which have included intra-articular injections [29, 30]. A recent study demonstrated that portal tract LIA led to significantly improved pain control as compared with a fascia iliac nerve block [31].

The purpose of this retrospective study is to determine the efficacy of a single extracapsular injection of bupivacaine–epinephrine during hip arthroscopy in reducing the rate of elective postoperative femoral nerve blocks. Targeting the highly innervated [29–31] hip capsule with LIA may improve postoperative pain control and reduce the necessity of other pain control modalities. We hypothesize that patients who receive a single extracapsular LIA injection during hip arthroscopy will receive fewer elective postoperative femoral nerve blocks as compared with patients who do not receive LIA. Secondary objectives of the study include measuring the immediate postoperative opioid consumption in patients treated with and without LIA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

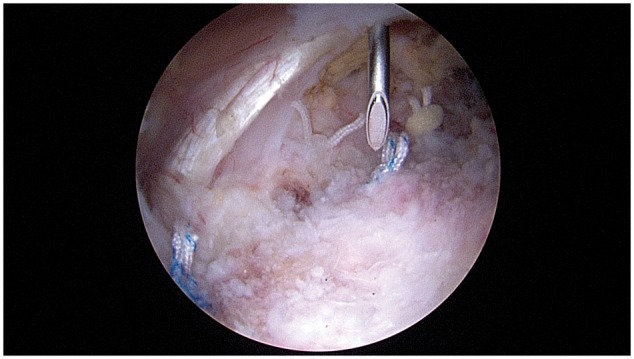

This was a single-center retrospective case–control study. With approval from the institutional review board, we identified 100 consecutive patients between the ages of 16 and 64 years who underwent a unilateral primary hip arthroscopy procedure between May 2015 and March 2016. The senior author began using the described LIA technique on all hip arthroscopy procedures starting in October 2015. Fifty patients from October 2015 to March 2016 were identified that received an extra-capsular LIA injection after repair of the hip capsule. Immediately after complete capsular closure, the spinal needle was arthroscopically placed in the space just anterior to the capsule (Fig. 1). Excess saline was suctioned out of the space followed by portal closure. After the portal closure, 20 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine–epinephrine (1 : 200 000) was injected into the extra-capsular space. Prior to this period, from May 2015 to September 2015, 50 hip arthroscopy patients that did not receive an LIA injection were identified. All procedures as well as the indications for the procedures were recorded. Patients were excluded for incomplete charting. Ultimately, 106 patients were reviewed with six charts being excluded due to incomplete charting. PACU opioid use was documented by the nursing staff and total perioperative consumption was calculated based on morphine milligram equivalents (MME) described by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [32, 33]. Pain scores were not standardized during this time in the PACU and were not retrospectively reviewed due to variations in nursing documentation.

Fig. 1.

LIA administration via spinal needle placed just anterior to the hip capsule.

Preoperatively, all patients received oral acetaminophen (975 mg), celecoxib (400 mg), pregabalin (150 mg) and tapentadol (100 mg) as part of our standard multimodal pain medication regimen at our institution [dosages varied appropriately with patient weight and body mass index (BMI)]. Patients in the intervention group received a 20-ml injection of 0.25% bupivacaine–epinephrine (1 : 200 000) in the tissue adjacent to the hip capsule after capsular closure had been performed. This was performed under direct visualization prior to closure of the portals. Patients in the control group did not receive an LIA injection. All surgical procedures were carried out by the senior author (SKA).

Postoperatively, patients were monitored in the PACU by nursing staff and their pain was addressed using primarily oral or intravenous (i.v.) pain medication per nursing staff discretion. If the patient’s pain was considered to be inadequately addressed using prescribed pain medications by both the nursing staff and the anesthesiology team, then a postoperative nerve block was performed by the anesthesiology team. Postoperative nerve blocks consisted of 25–50 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine with 5 μg/ml epinephrine with or without 4–8 mg dexamethasone.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and outcomes of interest were compared between LIA and non-LIA patient groups. Categorical variables were described in frequency and percentage, and were compared using a chi-squared test. Continuous variables were compared using a t-test or Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test as appropriate. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

There were no significant differences in gender, age or prior opioid use between the LIA and non-LIA groups. All baseline characteristics can be found in Table I. In the non-LIA group, 39 patients underwent femoracetabuloplasty with labral repair and 11 patients underwent femoracetabuloplasty without labral repair. In the LIA group, 40 patients underwent femoracetabuloplasty with labral repair, 8 patients underwent femoracetabuloplasty without labral repair, 1 patient underwent femoracetabuloplasty with lesser trochanteric osteochondroplasty and psoas tendon repair, and 1 patient underwent capsular repair and reconstruction using a MaxForce GraftJacket (Wright Medical Technology, Memphis, TN, USA).

Table I.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | LIA (N = 50) | Non-LIA (N = 50) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 14 (28) | 18 (36) | 0.39a |

| Female | 36 (72) | 32 (64) | |

| Surgery duration, hours, mean (SD) | 2.03 (0.49) | 2.02 (0.52) | 0.87b |

| PACU duration, hours, mean (SD) | 2.52 (1.17) | 2.33 (0.71) | 0.34b |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 25.47 (5.52) | 25.09 (5.71) | |

| Median (IQR) | 21.29 (24.15, 26.51) | 21.29 (24.15, 26.51) | 0.71c |

| Age at surgery, years, mean (SD) | 37.44 (11.59) | 33.64 (11.97) | 0.11b |

| Prior opioid use, n (%) | |||

| No | 44 (88) | 39 (78) | 0.18a |

| Yes | 6 (12) | 11 (22) | |

| Prior psych meds, n (%) | |||

| No | 36 (72) | 42 (84) | 0.15a |

| Yes | 14 (28) | 8 (16) | |

| Side of surgery, n (%) | |||

| Left | 21 (42) | 16 (32) | 0.30a |

| Right | 29 (58) | 34 (68) |

Distribution of BMI (right skewed).

Chi-squared test.

Two-sample t-test.

Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test.

There was a lower rate of PACU femoral nerve blocks in the LIA group versus the non-LIA group (0.34 versus 0.56, P = 0.027). However, there was no significant difference in PACU opioid consumption between the LIA and non-LIA groups (P = 0.740), who both consumed >14 MME during their stay in the PACU (Table II).

Table II.

Outcomes comparison

| Outcomes | LIA (N = 50) | Non-LIA (N = 50) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nerve block, n (%) | |||

| No | 33 (66) | 22 (44) | 0.027a |

| Yes | 17 (34) | 28 (56) | |

| PACU opioid use: MME, mean (SD) | 14.51 (9.73) | 14.08 (9.06) | 0.740b |

Bold entry to highlight significance.

Chi-squared test.

Two-sample t-test.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study supported our hypothesis that extracapsular LIA would significantly reduce the rate of elective postoperative femoral nerve blocks. However, the statistically equivalent PACU opioid consumption between study groups seemed to contradict the decreased use of femoral nerve blocks in the LIA group. One possible explanation is that the higher rate of nerve blocks in the control group confounded the opioid consumption findings, as patients who receive femoral nerve blocks are known to consume less opioids postoperatively [4].

Importantly, the preoperative use of opiate medications, as well as psychiatric medications, was equivalent between our study groups, eliminating a potential confounding factor. Although we did not directly measure the effects of prior opioid use on perioperative pain control, the negative effects of prior chronic opioid use on both immediate and longer term postoperative pain control have been well documented [34, 35].

Our findings add to the current literature supporting the potential postoperative pain relief with LIA. Garner et al. compared postoperative numeric pain scores in hip arthroscopy patients who received a portal LIA at the end stages of surgery versus a preoperative fascia iliaca compartment block (FICB). Both groups received 40 ml of 0.125% levobupivacaine for their respective injections. During an interim analysis, with 46 of 74 planned patients having been recruited, the mean pain score at 1 h postoperatively for the LIA group was 3.4 versus 5.5 for the FICB group (P = 0.02); enrollment in the study was subsequently stopped [36]. Previous studies have shown the FICB block to be effective in controlling pain following hip fractures [37] as well as hip arthroscopy procedures [38]. However, the study by Garner demonstrated that portal LIA may be even more efficacious than the FICB block, though this was within a limited cohort.

LIA strategies include both intra-articular and periarticular delivery. One concern regarding intra-articular injections is the potential chondrotoxic effects with intra-articular administration [39–43]; however, recent invivo animal models have failed to substantiate this [44, 45]. Consequently, there is interest in utilizing a periarticular injection to avoid the potential complication of chondrolysis. Two studies have compared postoperative pain relief with intra-articular versus periarticular LIA in hip arthroscopy patients. Shlaifer et al. utilized a pre-emptive block strategy for hip arthroscopy administering 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine in either the periarticular region or intra-articularly at the start of surgery. The patients who received a periacetabular block experienced significant reduction in their postoperative pain at 30 min and 18 h compared with those who received the intra-articular block, whereas there was no difference in pain scores at other time points [46]. In a similar study, Baker et al. compared hip arthroscopy patients who received either an intra-articular injection of bupivacaine or an injection of bupivacaine around the portal sites at the time of closure. At 1 and 2 h after surgery, there was no significant difference in Visual Analogue Scale pain between groups; however, at 6 h the portal LIA group had significantly less pain. Conversely, in the period immediately following surgery the portal LIA group required significantly more rescue analgesia [47].

In this study, 0.25% bupivacaine–epinephrine was injected under direct visualization into the tissue directly anterior to the hip capsule following capsular closure. We chose to target the capsule directly as it is known to be highly innervated [29, 31] and contain nociceptive fibers [31], making it a likely pain generator in hip arthroscopy. Therefore, the rationale of this approach to LIA in the hip is that it avoids potential chrondrolysis, while still targeting the most likely source of pain.

This study had several limitations, including the retrospective design and limited sample size. The hip arthroscopy and LIA procedures were carried out by a single-surgeon, which questions reproducibility. However, the LIA extracapsular injection is easily reproducible from a technical standpoint and the lack of multiple surgeons decreases variability in overall surgical technique. Although our PACU staff currently operate within a standardized protocol, nursing staff still exercise discretion in their administration of oral and i.v. pain medications, leading to inevitable variability across staff members. Standardized pre- and postoperative pain scores were not routinely collected during this study period, which would have allowed for more complete analysis, especially concerning which pain levels were associated with block decision, opioid consumption, etc. A patient’s decision to get a nerve block is multi-faceted and may not accurately reflect their pain level. Consequently, our results do not necessarily reflect actual pain levels experienced by the patient, but rather their utilization of pain management modalities. Finally, as the senior author began performing periarticular LIA in all patients after a certain time point, there is potential for other confounding factors with changes in surgical technique over time; however, no identifiable changes in technique were employed during the study time. During the study period, we elected to use 20 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine, as bupivacaine was the most cost efficient, long-acting local anesthetic available. We also selected a volume of 20 ml in order to allow for our block team to have the option of performing a nerve block in the immediate postoperative period if requested. We have since increased the volume of the extra-capsular injection to 30 ml of 0.5% bupivacaine with epinephrine.

The described use of LIA in this study is a low-cost and simple approach to manage postoperative pain in hip arthroscopy patients, taking advantage of the direct visualization of the joint capsule and needle placement at the end of the arthroscopic procedure. The decreased rate of postoperative nerve blocks suggests that an extracapsular LIA injection may be an effective tool in the postoperative pain management of hip arthroscopy patients.

FUNDING

University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 8UL1TR000105 (formerly UL1RR025764).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Montgomery SR, Ngo SS, Hobson T. et al. Trends and demographics in hip arthroscopy in the United States. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sing DC, Feeley BT, Tay B. et al. Age-related trends in hip arthroscopy: a large cross-sectional analysis. Arthroscopy 2015; 31: 2307–13 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khanduja V, Villar RN.. Arthroscopic surgery of the hip: current concepts and recent advances. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006; 88: 1557–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ward JP, Albert DB, Altman R. et al. Are femoral nerve blocks effective for early postoperative pain management after hip arthroscopy? Arthroscopy 2012; 28: 1064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Potter MQ, Sun GS, Fraser JA. et al. Psychological distress in hip arthroscopy patients affects postoperative pain control. Arthroscopy 2014; 30: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carr DB, Goudas LC.. Acute pain. Lancet 1999; 353: 2051–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pavlin DJ, Chen C, Penaloza DA. et al. Pain as a factor complicating recovery and discharge after ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg 2002; 95: 627–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Segerdahl M, Warren-Stomberg M, Rawal N. et al. Clinical practice and routines for day surgery in Sweden: results from a nation-wide survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2008; 52: 117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dold AP, Murnaghan L, Xing J. et al. Preoperative femoral nerve block in hip arthroscopic surgery: a retrospective review of 108 consecutive cases. Am J Sports Med 2014; 42: 144–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Auroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L. et al. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology 2002; 97: 1274–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liguori GA. Complications of regional anesthesia: nerve injury and peripheral neural blockade. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2004; 16: 84–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jeng CL, Torrillo TM, Rosenblatt MA.. Complications of peripheral nerve blocks. Br J Anaesth 2010; 105(Suppl. 1): i97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sharma S, Iorio R, Specht LM. et al. Complications of femoral nerve block for total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bianconi M, Ferraro L, Traina GC. et al. Pharmacokinetics and efficacy of ropivacaine continuous wound instillation after joint replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth 2003; 91: 830–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kerr DR, Kohan L.. Local infiltration analgesia: a technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: a case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008; 79: 174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bech RD, Ovesen O, Lindholm P. et al. Local anesthetic wound infiltration for pain management after periacetabular osteotomy. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial with 53 patients. Acta Orthop 2014; 85: 141–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen DW, Hu CC, Chang YH. et al. Intra-articular bupivacaine reduces postoperative pain and meperidine use after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 2457–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Murphy TP, Byrne DP, Curtin P. et al. Can a periarticular levobupivacaine injection reduce postoperative opiate consumption during primary hip arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012; 470: 1151–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Niemelainen M, Kalliovalkama J, Aho AJ. et al. Single periarticular local infiltration analgesia reduces opiate consumption until 48 hours after total knee arthroplasty. A randomized placebo-controlled trial involving 56 patients. Acta Orthop 2014; 85: 614–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. White S, Vaughan C, Raiff D. et al. Impact of liposomal bupivacaine administration on postoperative pain in patients undergoing total knee replacement. Pharmacotherapy 2015; 35: 477–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zoric L, Cuvillon P, Alonso S. et al. Single-shot intraoperative local anaesthetic infiltration does not reduce morphine consumption after total hip arthroplasty: a double-blinded placebo-controlled randomized study. Br J Anaesth 2014; 112: 722–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Andersen LJ, Poulsen T, Krogh B. et al. Postoperative analgesia in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized double-blinded, placebo-controlled study on peroperative and postoperative ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline wound infiltration. Acta Orthop 2007; 78: 187–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Novais EN, Kestel L, Carry PM. et al. Local infiltration analgesia compared with epidural and intravenous PCA after surgical hip dislocation for the treatment of femoroacetabular impingement in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 2018; 38: 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reilly KA, Beard DJ, Barker KL. et al. Efficacy of an accelerated recovery protocol for Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty–a randomised controlled trial. Knee 2005; 12: 351–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Busch CA, Shore BJ, Bhandari R. et al. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection in total knee arthroplasty. A randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 959–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vendittoli PA, Makinen P, Drolet P. et al. A multimodal analgesia protocol for total knee arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 282–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marques EM, Jones HE, Elvers KT. et al. Local anaesthetic infiltration for peri-operative pain control in total hip and knee replacement: systematic review and meta-analyses of short- and long-term effectiveness. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 220.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersen LO, Kehlet H.. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2014; 113: 360–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Birnbaum K, Prescher A, Hessler S. et al. The sensory innervation of the hip joint–an anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat 1997; 19: 371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kampa RJ, Prasthofer A, Lawrence-Watt DJ. et al. The internervous safe zone for incision of the capsule of the hip. A cadaver study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89: 971–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haversath M, Hanke J, Landgraeber S. et al. The distribution of nociceptive innervation in the painful hip: a histological investigation. Bone Joint J 2013; 95-B: 770–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R.. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain–United States, 2016. JAMA 2016; 315: 1624–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Broglio K. Approximate dose conversions for commonly used opioids. In: Post T. (ed.). Waltham, MA: UpToDate, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zywiel MG, Stroh DA, Lee SY. et al. Chronic opioid use prior to total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 1988–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim KY, Anoushiravani AA, Chen KK. et al. Preoperative chronic opioid users in total knee arthroplasty-which patients persistently abuse opiates following surgery? J Arthroplasty 2018; 33: 107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garner M, Alsheemeri Z, Sardesai A. et al. A prospective randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of fascia iliaca compartment block versus local anesthetic infiltration after hip arthroscopic surgery. Arthroscopy 2017; 33: 125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Monzón DG, Vazquez J, Jauregui JR. et al. Pain treatment in post-traumatic hip fracture in the elderly: regional block vs. systemic non-steroidal analgesics. Int J Emerg Med 2010; 3: 321–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krych AJ, Baran S, Kuzma SA. et al. Utility of multimodal analgesia with fascia iliaca blockade for acute pain management following hip arthroscopy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22: 843–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chu CR, Izzo NJ, Coyle CH. et al. The in vitro effects of bupivacaine on articular chondrocytes. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008; 90: 814–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chu CR, Izzo NJ, Papas NE. et al. In vitro exposure to 0.5% bupivacaine is cytotoxic to bovine articular chondrocytes. Arthroscopy 2006; 22: 693–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lo IK, Sciore P, Chung M. et al. Local anesthetics induce chondrocyte death in bovine articular cartilage disks in a dose- and duration-dependent manner. Arthroscopy 2009; 25: 707–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Buchko JZ, Gurney-Dunlop T, Shin JJ.. Knee chondrolysis by infusion of bupivacaine with epinephrine through an intra-articular pain pump catheter after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2015; 43: 337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gomoll AH, Kang RW, Williams JM. et al. Chondrolysis after continuous intra-articular bupivacaine infusion: an experimental model investigating chondrotoxicity in the rabbit shoulder. Arthroscopy 2006; 22: 813–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Iwasaki K, Sudo H, Kasahara Y. et al. Effects of multiple intra-articular injections of 0.5% bupivacaine on normal and osteoarthritic joints in rats. Arthroscopy 2016; 32: 2026–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gomoll AH, Yanke AB, Kang RW. et al. Long-term effects of bupivacaine on cartilage in a rabbit shoulder model. Am J Sports Med 2009; 37: 72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shlaifer A, Sharfman ZT, Martin HD. et al. Preemptive analgesia in hip arthroscopy: a randomized controlled trial of preemptive periacetabular or intra-articular bupivacaine in addition to postoperative intra-articular bupivacaine. Arthroscopy 2017; 33: 118–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Baker JF, McGuire CM, Byrne DP. et al. Analgesic control after hip arthroscopy: a randomised, double-blinded trial comparing portal with intra-articular infiltration of bupivacaine. Hip Int 2011; 21: 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]