ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study was to determine the outcomes following segmental labral reconstruction (labral defects measuring <1 cm) using a segment of capsular tissue or a segment of the indirect head of rectus femoris tendon. Eleven patients (five females and six males) underwent segmental labral reconstruction using a segment of capsule (eight patients) or indirect head of rectus tendon (three patients) by a single surgeon from March 2005 to October 2012. The average age of the patients was 35 years old (range, 20–51 years). Data collected included the pre- and post-operative Hip Outcome Score (HOS-ADL and HOS-SS), the modified Harris Hip Score and patient satisfaction rate (1 = unsatisfied, 10 = very satisfied), complications, necessity of revision hip arthroscopy and conversion to total hip arthroplasty. Average follow-up time was at 62 months (range, 9–120 months). No patient required revision hip arthroscopy or converted to total hip arthroplasty. The HOS-ADL significantly improved from 73 to 89 (P < 0.05). The HOS-SS showed significant improvement from 52 to 79 and the modified Harris Hip Score significantly improved from 66 to 89. Median patient satisfaction rate was 9 out of 10 (range, 3–10). In a small sample, the arthroscopic hip segmental labral reconstruction showed significant improvement in patient-reported outcomes. This treatment provides an option in cases of small labrum defects (<1 cm) or deficits in patients while providing improved function and high patient satisfaction.

INTRODUCTION

It has been shown that the acetabular labrum plays a crucial role in hip joint biomechanics and overall physiologic function [1–3]. The labrum deepens the acetabulum while extending coverage of the femoral head and is responsible for the fluid seal, which ensures adequate joint lubrication [1]. Furthermore, it distributes load and pressures within the acetabulum and enhances stability by providing negative intra-articular pressure within the hip joint [4]. A previous cadaveric study evaluated the effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection and reconstruction on hip fluid pressurization and reported that partial labral resection caused a significant decrease in intra-articular fluid pressurization [5].

Labral tissue should be preserved since a labral deficient joint has been associated with accelerated degenerative changes in the hip joint [6]. With the improved understanding of the labrum’s role for a proper joint functioning, labral preserving techniques are increasingly being reported to result in successful outcomes [7, 8]. When the labrum is absent, severely deficient or simply irreparable, an alternative approach should be utilized. Labral reconstruction, therefore, has recently emerged to address this subset of patients, in order to alleviate the pain and improve joint biomechanics to ultimately prevent accelerated joint degeneration [9].

Different labrum reconstruction techniques have been described in the literature in the past few years. Philippon et al. [10] and Geyer et al. [11] described an arthroscopic technique using iliotibial band autograft with promising early and mid-term results. Matsuda [12] described an arthroscopic technique using gracilis autograft. Sierra and Trousdale [13] reported an open technique using the autograft ligamentum teres. Domb et al. [14] described a method of arthroscopic labral reconstruction using local capsular autograft tissue, which is used for defects measuring 10–20 mm. Recently, Sharfman et al. [15] reported a labral reconstruction technique using an autologous indirect head of the rectus femoris. However, these studies did not report outcomes following the procedures.

In cases of small labral defects (<1 cm), a labral reconstruction using an autologous graft from a segment of capsular tissue or a segment of the indirect head of the rectus femoris tendon can be performed. The purpose of this study was to determine the outcomes and failure rates following segmental labral reconstruction using a segment of capsular tissue or a segment of the indirect head of rectus femoris tendon.

METHODS

A group of 11 patients underwent segmental labral reconstruction using a segment of capsule or indirect head of rectus tendon by a single surgeon (initials blinded for review) between March 2005 and October 2012 were included in the study. All data were prospectively collected and retrospectively reviewed. Patients who underwent labral repair and labral reconstruction with autograft and allograft iliotibial band were excluded. Data collected included the pre- and post-operative Hip Outcome Score (HOS-ADL and HOS-SS), the modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS) and patient satisfaction rate (1 = unsatisfied, 10 = very satisfied), complications, necessity of revision hip arthroscopy and conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Patients were positioned in a modified supine position on a traction table. The anterolateral and mid-anterior portals were used to gain access into the hip. A thorough diagnostic evaluation of the hip was performed using a 70° arthroscope. After addressing additional pathological lesions such as bony impingement, cartilage lesions, lysis of adhesions and/or synovectomy, attention was focused on the labral reconstruction. Acetabuloplasty and rim trimming were performed if indicated. Acetabular chondral defects were treated with debridement of any unstable cartilage flaps. The area to be reconstructed was debrided, attempting to make the smallest reconstruction area possible.

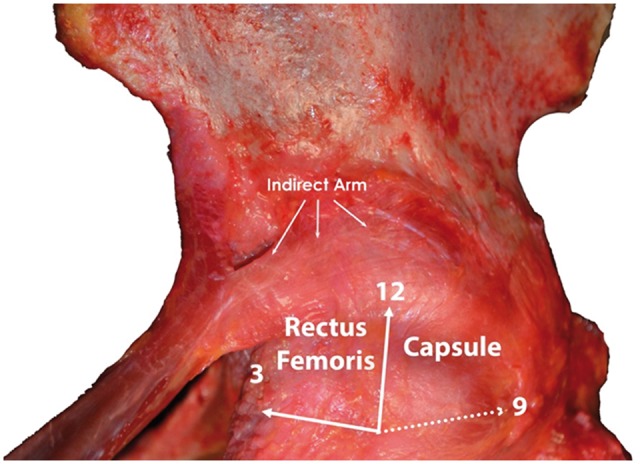

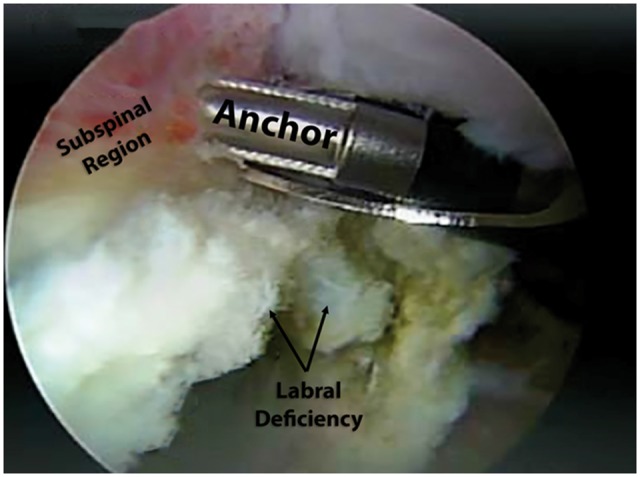

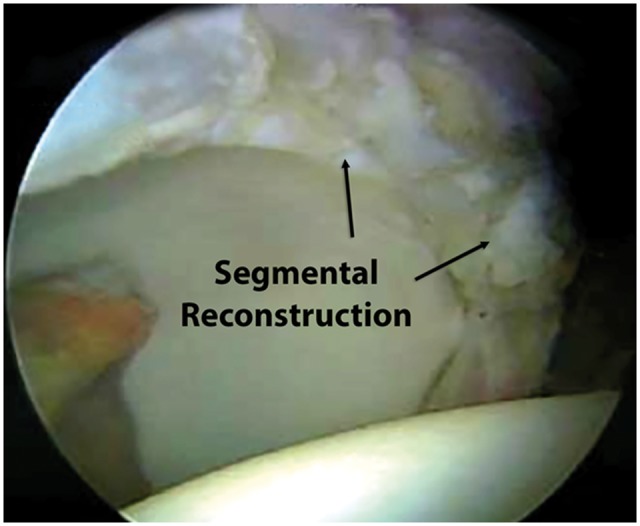

The segmental reconstruction is indicated for labral deficiencies measuring <1 cm with a centre-edge angle measuring >25°. The indirect head of the rectus femoris tissue was the choice when the deficiency was placed between 12 and 3 o’clock position in the acetabulum (Fig. 1). The tendon was isolated from the capsule and the first suture anchor was placed at the defect site and both extremities of the suture are passed through the tendon and then fixed to the rim. An arthroscopic knife was used to split the tendon in parallel to the longitudinal fibres, and if necessary, other suture anchors are placed to improve graft fixation, as necessary. In cases which the labrum defect was placed between 9 and 12 o’ clock position, a small segment of hip capsule was the choice. After the rim trimming and the labrum defect were measured, a suture anchor was placed on the defect site (Fig. 2) and the sutures were passed through the capsule with an arthroscopic pierce tool. Sequentially, the knot was tight placing the capsule in order to fill the defect (Fig. 3). The capsular tissue along the acetabular rim is often sufficient to cover the defect with a similar thickness such as the native labrum, avoiding persistent labrum deficiency.

Fig. 1.

Anatomic demonstration of the possible donor sites for segmental reconstruction for labrum defects measuring <1 cm.

Fig. 2.

Arthroscopic view showing the labral deficiency and the anchor placement for segmental reconstruction using capsular tissue as a local graft.

Fig. 3.

Arthroscopic view after the segmental reconstruction with capsular tissue.

RESULTS

The average age of the patients was 35 years old (range, 20–51 years) with five females and six males. Eight patients underwent segmental reconstruction with capsular tissue and in three patients a segment of the indirect head of the rectus femoris was used. The average alpha angle was 67° (range, 40°–86°). The average centre-edge angle was 42° (range, 32°–69°). One patient had a hip joint space measuring <2 mm. This patient was operated on early in the series, before research had shown that 2 mm of less of joint space should be a contraindication. This patient was a male marathon runner, age 31 years at the time of hip arthroscopy. At 5 years following segmental reconstruction, this patient had good joint space and a HOS-ADL score of 85.

All patients completed follow-up. Average follow-up time was 65 months (range, 12–120 months). All patients completed follow-up. No patient required revision hip arthroscopy or converted to THA. The ADL-HOS significantly improved from 73 to 89 (P < 0.05). The Sport HOS showed significant improvement from 52 to 79 and the mHHS significantly improved from 66 to 89. Median satisfaction rate was 9 out of 10 (range, 3–10). No case of rectus femoris tendonitis was reported (Table I).

Table I.

Demographic characteristics, preoperative and postoperative outcome scores on 10 patients who completed follow-up

| Capsular tissue | Age | Sex | MHHS pre-op | HOS-ADL pre-op | HOS-SS pre-op | Months post-op | MHHS post-op | HOS-ADL post-op | HOS-SS | Patient satisfaction [1–10] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 20 | F | 63 | 50 | 32 | 110 | 96 | 92 | 94 | 9 |

| Patient 2 | 51 | M | 67 | 86 | 56 | 134 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 10 |

| Patient 3 | 50 | M | 70 | 81 | 43 | 123 | 98 | 98 | 100 | 10 |

| Patient 4 | 31 | M | 43 | 46 | 55 | 96 | 92 | 90 | 61 | 3 |

| Patient 5 | 25 | F | 61 | 62 | 61 | 36 | 79 | 57 | 13 | 9 |

| Patient 6 | 47 | F | 92 | 95 | 70 | 15 | 96 | 90 | 91 | 9 |

| Patient 7 | 22 | F | 79 | 78 | 50 | 12 | 81 | 90 | 90 | 9 |

| Patient 8 | 31 | M | 67 | 68 | 61 | 47 | 86 | 70 | 50 | 5 |

| Indirect head of rectus | Age | Sex | MHHS | HOS-ADL | HOS-SS | mHHS | HOS-ADL | HOS-SS | Patient satisfaction [1–10] | |

| Patient 1 | 41 | M | 52 | 73 | 52 | 20 | 74 | 87 | 75 | 8 |

| Patient 2 | 40 | F | 69 | 78 | 57 | 61 | 85 | 100 | 94 | 9 |

| Patient 3 | 31 | M | 59 | 89 | 86 | 61 | 65 | 85 | 80 | 7 |

DISCUSSION

In this small group of patients, the arthroscopic hip segmental labral reconstruction using capsular tissue or segment of indirect head of rectus femoris tendon resulted significant improvement in patient-centred outcomes. This treatment constitutes a treatment option in cases of labral defects <1 cm in non-dysplastic patients while providing improved function and high patient satisfaction.

Meticulous management of the labral tissue has become a guiding principle in hip arthroscopic surgery given the recent understanding of the importance of the acetabular labral hydraulic seal [1–4]. It has been reported that patients who have previously undergone partial labral resections have shown a faster progression of hip arthritis [5]. In patients with deficient labral tissue often due to ossification, a hypotrophic or degenerative native labrum, iatrogenic postsurgical causes or revision situations, labral reconstruction has emerged as a viable solution for symptoms of microinstability, pain and discomfort associated with this pathology [6, 7]. Philippon et al. [5] and Nepple et al. [16] reported that labral reconstruction significantly improves hip intra-articular fluid pressurization, potentially reducing hip contact pressures and thus enhances distractive stability.

Several grafts had been described in the literature including iliotibial band, semitendinosus, gracilis, indirect head of the rectus femoris and anterior tibialis tendons displayed similar cyclic elongation behaviour in response to simulated physiologic forces. Utilizing a portion of the capsule has the advantage of avoiding donor-site morbidity by using locally available tissue if an autograft is planned, decreasing postoperative pain, scarring and blood loss [14]. The main shortcoming of this technique is the inability to close the capsule and therefore it should not be used in patients with a lateral centre-edge angle of <25°. If patients undergo periacetabular osteotomy prior to hip arthroscopy, this technique may still be considered. This technique is not considered in patients with uncorrected dysplasia. The utilization of capsule tissue as a graft source for defects measuring >1 cm may entail other complications such as microinstability and pain due to muscle invagination into the joint during flexion and consequently, the necessity of an additional procedure to perform capsular reconstruction. Therefore, in defects larger than 1 cm, an iliotibial band autograft is preferable.

A recent technique article described the hip labral reconstruction using the reflected head of the rectus femoris tendon as a minimally invasive surgical procedure that is applicable in all patients undergoing hip labral reconstruction. There is no donor site morbidity as the harvesting and fixation are completed through the same portals. Retaining the blood supply of the graft is another added benefit; however, they did not present outcome results [15]. In our series, the indirect head of rectus was utilized when the defect was located between 12’ and 3’o clock position in the acetabulum. Three patients in this subset of patients underwent labral reconstruction with indirect head of the rectus femoris autograft with no complications and good clinical results. However, some technical details must be taken into consideration, such as to perform a complete release of the tendon to avoid rectus femoris tendonitis. Controlling the graft thickness and length of the graft can be challenging, leading to an insufficient reconstruction and consequently, treatment failure.

A previous study on labral reconstruction with an iliotibial band autograft at minimum 3-year follow-up reported that among 76 hips, 19 progressed to THA at an average of 28 months from the procedure [11]. Follow-up on the surviving hips was available for 49 patients (86%) with a mean follow-up time of 49 months (range, 36–70 months). The mHHS significantly increased from a preoperative mean of 58.9 to the most recent follow-up score averaging 83 (P = 0.0001), Median patient satisfaction with outcome was 8 (11). The present study had an average follow-up time of 62 months (range, 9–120 months). No patient required a revision hip arthroscopy or converted to THA, mHHS significantly improved from 66 to 89, and the median patient satisfaction rate was 9. Although, in a small sample, this segmental reconstruction with local tissue showed similar results when compared with a previous studied technique.

This study is not without limitations such as the retrospective character of the data and the lack of a control group and the small sample. Furthermore, additional procedures performed at the time of the surgery may also have an effect on the outcome of the surgery independent of the labral reconstruction. It was not possible to group patients by other pathology due to the small sample. Finally, while patient-reported outcomes were analysed, there were no objective measures of labrum healing or intra-articular status performed with magnetic resonance imaging or any other imaging method.

In conclusion, in this small sample, the arthroscopic hip segmental labral reconstruction using capsular tissue or the indirect head of rectus tendon showed significant improvement in outcomes. This treatment provides an option in cases of small labrum defects (<1 cm) and deficiencies in non-dysplastic patients while providing improved function and high patient satisfaction.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M.J.P. receives research support from National Institute of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institute of Aging, Smith and Nephew Endoscopy, Ossur, Arthrex, Siemens and Royalties from Bledsoe, ConMed Linvatec, DonJoy, SLACK Iinc., Elsevier. M. J. Philippon is stockholder of Arthrosurface, MJP Innovations, LLC, MIS, Vail Valley Medical Center-Governing. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R. et al. The acetabular labrum seal: a poroelastic finite element model. Clin Biomech 2000; 15: 463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R. et al. An in vitro investigation of the acetabular labral seal in hip joint mechanics. J Biomech 2003; 36: 171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferguson SJ, Bryant JT, Ganz R. et al. The influence of the acetabular labrum on hip joint cartilage consolidation: a poroelastic finite element model. J Biomech 2000; 33: 953–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Philippon MJ. The role of arthroscopic thermal capsulorrhaphy in the hip. Clin Sports Med 2001; 20: 817–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philippon MJ, Nepple JJ, Campbell KJ. et al. The hip fluid seal—Part I: the effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection, and reconstruction on hip fluid pressurization. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22: 722–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarthy JC, Noble PC, Schuck MR. et al. The Otto E. Aufranc Award: the role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; 393: 25–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larson CM, Giveans MR, Stone RM.. Arthroscopic debridement versus refixation of the acetabular labrum associated with femoroacetabular impingement: mean 3.5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 1015–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Espinosa N, Rothenfluh DA, Beck M. et al. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement: preliminary results of labral refixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88: 925–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ayeni OR, Alradwan H, de Sa D. et al. The hip labrum reconstruction: indications and Outcomes – A systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 22: 737–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Philippon MJ, Briggs KK, Hay CJ. et al. Arthroscopic labral reconstruction in the hip using iliotibial band autograft: technique and early outcomes. Arthroscopy 2010; 26: 750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geyer MR, Philippon MJ, Fagrelius TS. et al. Acetabular Labral Reconstruction With an Iliotibial Band Autograft - Outcome and Survivorship Analysis at Minimum 3-Year Follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2013; 41: 1750–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matsuda DK. Arthroscopic labral reconstruction with gracilis autograft. Arthrosc Tech 2012; 1: e15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sierra RJ, Trousdale RT.. Labral reconstruction using the ligamentum teres capitis: report of a new technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 753–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Domb BG, Gupta A, Stake CE. et al. Arthroscopic labral reconstruction of the hip using local capsular autograft. Arthrosc Tech 2014; 3: e355–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sharfman ZT, Amar E, Sampson T. et al. Arthroscopic labrum reconstruction in the hip using the indirect head of rectus femoris as a local graft: surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech 2016; 5: e361–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nepple JJ, Philippon MJ, Campbell KJ. et al. The hip fluid seal–part II: the effect of an acetabular labral tear, repair, resection, and reconstruction on hip stability to distraction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2014; 2: 730–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]