Abstract

The Rv2633c gene in Mycobacterium tuberculosis is rapidly up-regulated after macrophage infection, suggesting that Rv2633c is involved in M. tuberculosis pathogenesis. However, the activity and role of the Rv2633c protein in host colonization is unknown. Here, we analyzed the Rv2633c protein sequence, which revealed the presence of an HHE cation-binding domain common in hemerythrin-like proteins. Phylogenetic analysis indicated that Rv2633c is a member of a distinct subset of hemerythrin-like proteins exclusive to mycobacteria. The Rv2633c sequence was significantly similar to protein sequences from other pathogenic strains within that subset, suggesting that these proteins are involved in mycobacteria virulence. We expressed and purified the Rv2633c protein in Escherichia coli and found that it contains two iron atoms, but does not behave like a hemerythrin. It migrated as a dimeric protein during size-exclusion chromatography. It was not possible to reduce the protein or observe any evidence for its interaction with O2. However, Rv2633c did exhibit catalase activity with a kcat of 1475 s−1 and Km of 10.1 ± 1.7 mm. Cyanide and azide inhibited the catalase activity with Ki values of 3.8 μm and 37.7 μm, respectively. Rv2633c's activity was consistent with a role in defenses against oxidative stress generated during host immune responses after M. tuberculosis infection of macrophages. We note that Rv2633c is the first example of a non-heme di-iron catalase, and conclude that it is a member of a subset of hemerythrin-like proteins exclusive to mycobacteria, with likely roles in protection against host defenses.

Keywords: catalase, metalloenzyme, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, reactive oxygen species (ROS), enzyme kinetics, hemerythrin, non-heme iron

Introduction

The gene designated as Rv2633c in Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (Mtb) has been shown to be rapidly up-regulated during infection following phagocytosis of the bacterium by macrophages (1, 2). It was subsequently shown to be up-regulated during in vitro acidification during macrophage infection (3). Further evidence for a critical role for the Rv2633c protein during in vivo infection stems from a transposon mutation screen that revealed that Mtb with Tn insertions inactivating Rv2633c was significantly attenuated (4). Despite the relevance of this protein to the pathogenicity of Mtb, this protein has not been previously isolated and its physiological function is unknown. The results described above suggest the possibility that Rv2633c may play an important role in the adaptation to host-derived antimicrobial mechanisms such as phagosomal acidification and reactive oxygen species. Mtb has multiple strategies to combat the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species that the host uses as a defense against this pathogen. These include protein defenses, a catalase-peroxidase (KatG), superoxide dismutase, and peroxiredoxins (5, 6). Mycobacteria also use mycothiol, which is a thiol present within the cytoplasm that creates a reducing environment for a defense against oxidative stress (7). The results described above, combined with our findings in this study, strongly suggest that Rv2633c is also an important component of the defense strategy against oxidative stress.

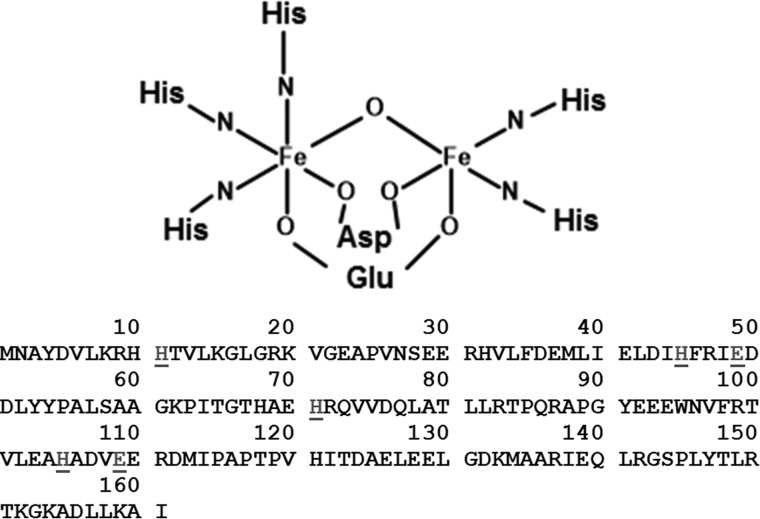

Analysis of the sequence of the protein encoded by the Rv2633c gene, which is presented in this paper, reveals the presence of an HHE cation-binding domain that is common in hemerythrins and hemerythrin-like proteins. Contrary to their name, hemerythrins do not contain heme but instead have a di-iron center which is used to bind oxygen (8). These HHE domains are 4-α-helical bundles that provide a pocket in which O2 binds to an oxygen-bridged di-iron site. The irons are typically coordinated within the HHE domain via the carboxylate side chains of a Glu and an Asp, and five His residues (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of the typical di-iron binding site of hemerythrin and primary sequence of the Rv2633c protein. Within the HHE cation-binding domain of hemerythrin one iron is coordinated by nitrogens from three histidine residues and oxygens from aspartate and glutamate residues. The other iron is coordinated and by nitrogens from two other histidine residues and oxygens from the same aspartate and glutamate residues. There is also an oxygen bridging the two irons (8). The amino acid sequence of Rv2633c derived from the gene sequence is presented with the residues characteristic of the HHE domain underlined.

The hemerythrin domain is found in a wide range of organisms and has been shown to have functions including oxygen binding, iron sequestration, and chemotaxis. Hemerythrins were first found in certain species of marine invertebrates: Sipuncula (peanut worm), Priapulida, Brachiopoda, and several different annelids (9, 10). Similar proteins have since been identified in bacterial species, as well as in some archaea (11). It is apparent that hemerythrin-like domains have been adapted for a broad range of functions. The first bacterial hemerythrin-like protein to be studied was McHr from Methylococcus capsulatus (12). It was predicted to be a transporter that delivers O2 to the particulate methane monooxygenase for methane oxidation (12). Desulfovibrio vulgaris is an anaerobic bacterium that uses a hemerythrin-like domain to signal chemotaxis. When the hemerythrin-like domain binds O2, this initiates a cascade that alters the swimming behavior of the cell away from O2 (13). The ovohemerythrin protein YP14 is hypothesized to serve as an iron storage protein during the development of Theromyzon tessulatum, a species of leech (14). A hemerythrin-like protein found in Mycobacterium smegmatis, MsmHr, was shown to regulate the expression of the sigma factor SigF in response to H2O2 rich environments. Studies in which the gene was knocked out, overexpressed, or mutated demonstrated a correlation between the levels of the protein and susceptibility to oxidative stress (15). That protein has not been isolated and it should be noted that there is not significant sequence similarity in the overall protein sequence between Rv2633c and MsmHr.

In this study, the recombinant Rv2633c protein was cloned from Mtb, expressed in Escherichia coli and purified. Physical properties of the protein were determined and an enzymatic activity was identified. The results indicate that Rv2633c is a non-heme di-iron protein that functions as a catalase. Furthermore, sequence and phylogenetic analysis presented herein reveals that Rv2633c is a member of a subset of hemerythrin-like proteins exclusive to mycobacteria, including known pathogens.

Results

Sequence and phylogenetic analyses

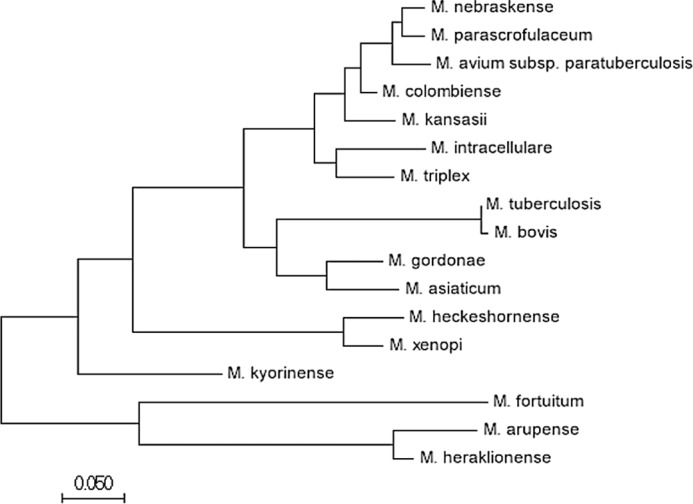

Inspection of the primary sequence of Rv2633c revealed the presence of an HHE cation-binding domain that is common in hemerythrins (Fig. 1). A basic local alignment search tool (BLAST)2 search was used to compare the hemerythrin-like domain in Rv2633c to conserved sequences, and the constraint-based multiple alignment tool (COBALT) was used to create a multiple sequence alignment of proteins with sequences most related to Rv2633c. Protein alignments of Rv2633c, excluding Mtb, returned highly similar sequences of putative proteins in other closely related Mycobacterium species. A BLAST protein search, excluding all mycobacterium species, yielded no sequences with similarity comparable to those of the mycobacteria. Thus, Rv2633c and the similar genes from Mycobacteria represent a distinct subclass of hemerythrin-like proteins. These genes are each annotated as hypothetical proteins with hemerythrin and hemerythrin-like domains, with no known structure or function. Alignment of the sequence of the protein encoded by the Rv2633c with its homologs in other mycobacteria (Fig. S1) revealed an interesting finding. The close homologs are present in pathogenic and opportunistic species. In contrast, M. smegmatis does not contain a gene with significant similarity to Rv2633c. Moreover, no other species of bacteria have a gene product with statistically significant homology across the entire protein sequence. This analysis strongly suggests that the gene product of Rv2633c is involved in the unique ability of opportunistic and authentic pathogens of this clade. A phylogenetic tree of these proteins based on alignment is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of Rv2633c from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and its nearest orthologs by the Maximum Likelihood method. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model (26). After the sequences were identified by BLAST, evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (27) to generate data for both this phylogenetic analysis and the protein sequence alignment (Fig. S1). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 17 amino acid sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were 158 positions in the final dataset.

Physical properties of the Rv2633c protein

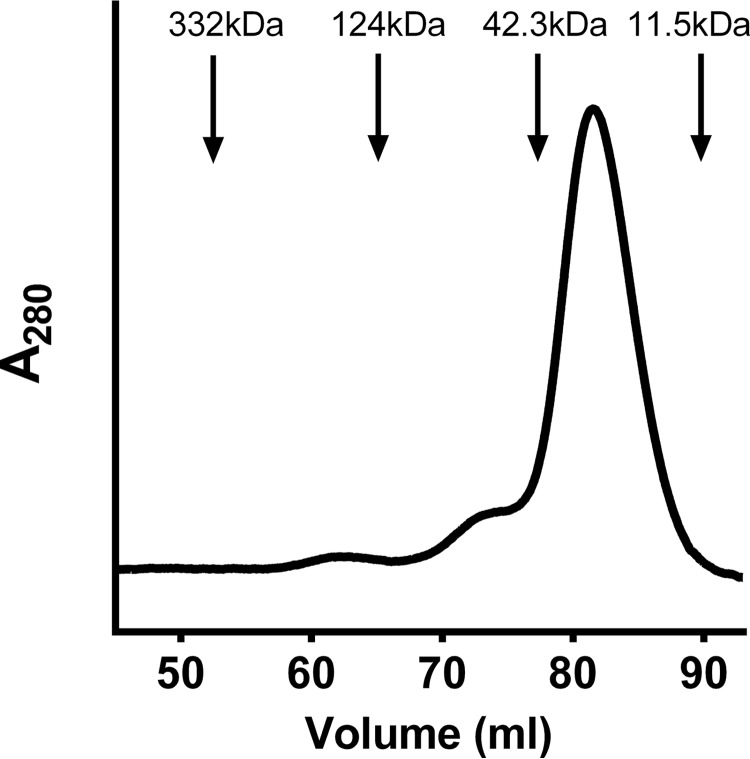

The yield of the purified protein was ∼1 mg from each liter of cell culture. The predicted molecular mass from the sequence of Rv2633c, including the hexahistidine tag, is 19,064 Da. The purified protein migrated on SDS-PAGE as a single band of approximately that mass. When subjected to analytical size-exclusion chromatography (Fig. 3) it migrated with an apparent mass of ∼36.5 ± 3.9 kDa (average of results from three different protein preparations). This suggests that the native form of the protein is a homodimer. The observation that Rv2633c elutes as a dimer is noteworthy, as hemerythrins which act as O2 carriers typically exist as octomers (8). The metal content of the purified protein was determined using sector-field ICP-MS for the presence of copper, iron, manganese, nickel, and zinc. The sulfur content of each sample was also determined so that molar metal/protein ratio of each metal could be accurately determined by comparison with the known sulfur content of the protein that was determined from the number of Met and Cys residues in the protein. The purified Rv2633c contained 1.7 ± 0.2 iron per protein molecule and no significant amounts of the other metals. The irons were tightly bound, and were not removed by exposure to 25 mm EDTA. These results are consistent with a tightly bound di-iron site.

Figure 3.

Size exclusion chromatography of Rv2633c. The positions of elution of molecular weight marker proteins are indicated. Rv2633c eluted with an apparent mass of 36.5 kDa.

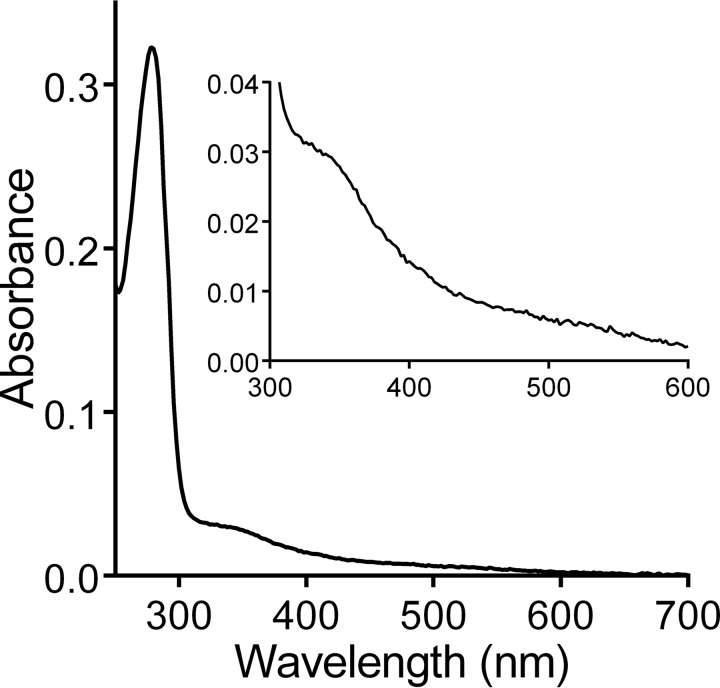

The purified protein exhibited an absorbance spectrum with a broad absorbance between 300–360 nm (Fig. 4). This feature is characteristic of oxygen-bridged dinuclear iron systems in the ferric state and is believed to result from an oxo to FeIII charge transfer transition (16). No spectral change was observed after addition of a large excess of a variety of strong reductants: sodium dithionite, dithiothreitol, and tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine. Furthermore, Rv2633c showed no reactivity toward O2, as judged by the lack of change of the absorbance spectrum after removal of the excess reductant and exposure to air. These results indicate that the protein environment of the metal site strongly stabilizes the diferric state of the protein. These properties are not consistent with the typical physiological role of hemerythrins, which is to bind and transport O2. They are also not consistent with a possible function as an O2 sensor.

Figure 4.

Absorbance spectrum of Rv2633c. The absorbance spectrum of the as-isolated protein is shown with the portion of the spectrum exhibiting absorbance attributed to the di-iron site magnified in the inset.

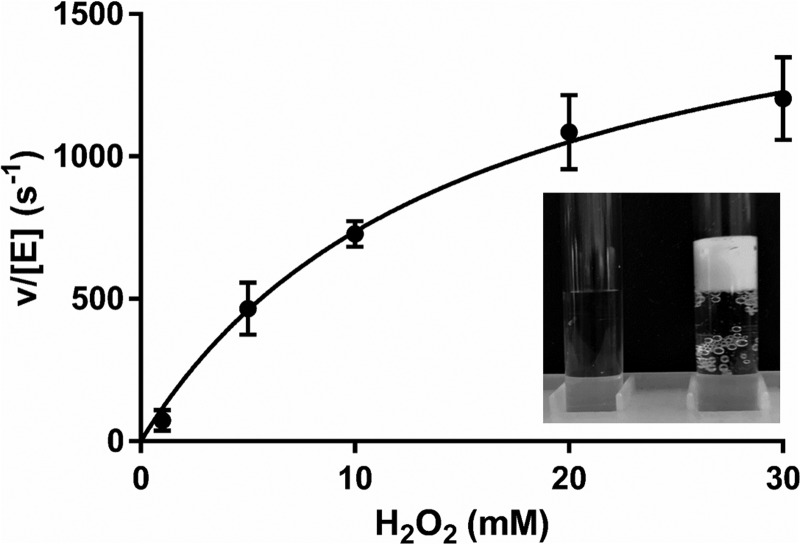

Enzymatic properties of Rv2633c

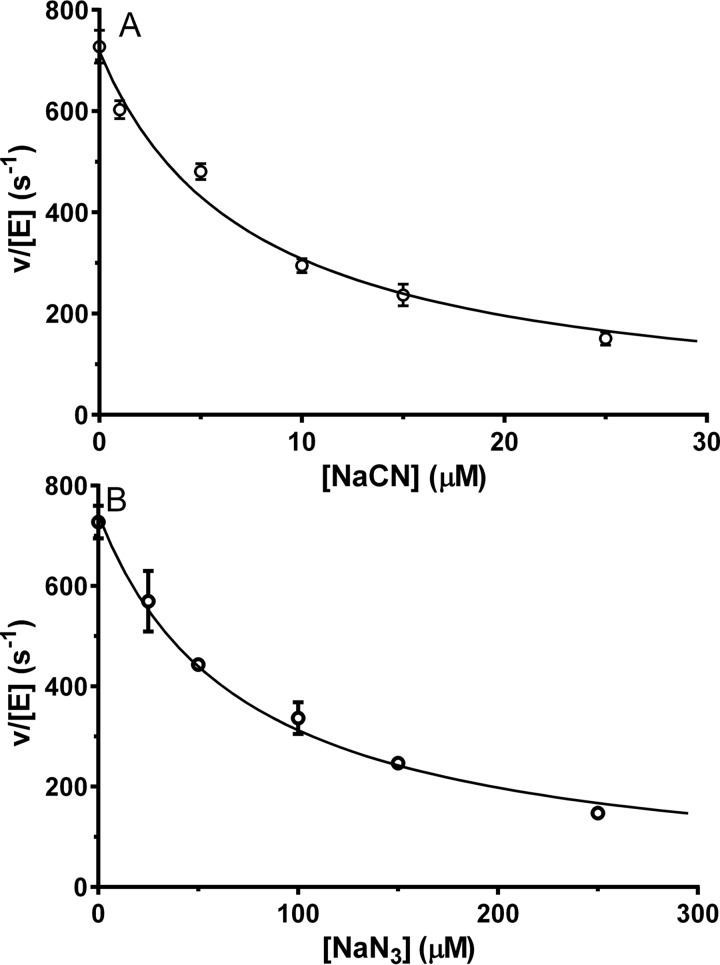

Catalase activity of Rv2633c was suspected as formation of bubbles and foam was observed on addition of H2O2 to solutions of the protein (Fig. 5). Catalase activity is typically measured by monitoring H2O2 consumption by one of two methods. One is a discontinuous assay in which aliquots are removed from the mixture at time points and then used in a reaction which gives rise to a color change that is proportional to [H2O2]. The other, used in this study, is a continuous assay that directly measures [H2O2] by monitoring its absorbance at 240 nm, which provides a more accurate measurement and far more time points. However, bubbles can interfere with the measurement. To avoid this interference during the spectrophotometric catalase assay, a very low concentration of enzyme (1 nm) was used. A steady-state kinetic analysis of the catalase activity of Rv2633c was performed and yielded values of kcat = 1475 ± 96 s−1 and Km = 10.1 ± 1.7 mm (Fig. 5). At concentrations of H2O2 higher than 30 mm, an initial rate could not be accurately determined because the absorbance of the initial concentration of H2O2 was >1.3 and outside the linear range. However, the data that were obtained fit very well to the Michaelis-Menten equation with an R2 value of 0.993. Two compounds which are known to inhibit heme-dependent catalases, cyanide and azide, were tested as inhibitors of Rv2633c activity. In each case, inhibition was observed (Fig. 6). IC50 values were determined empirically from the decrease in initial rate at increasing concentrations of inhibitor and used to calculate Ki with eq 2. For NaCN, an estimated IC50 value of 7.2 μm was used to determine a Ki value of 3.6 μm. Alternatively, direct analysis of the data by eq 3 yielded a Ki value of 3.8 ± 0.4 μm. For NaN3, an estimated IC50 value of 75.1 μm was used to determine a Ki value of 37.5 μm. Direct analysis of the data by eq 3 yielded a Ki value of 37.7 ± 3.9 μm. The close agreement in Ki values for each inhibitor that were obtained using eqs 2 and 3 supports the validity of the values, and is consistent with cyanide and azide each acting as a tight-binding inhibitor. In contrast to the pronounced changes in the Soret region of the absorbance spectrum that these inhibitors induce in heme-dependent catalases, addition of up to 1 mm cyanide or azide had little effect on the relatively nondescript visible absorbance spectrum of Rv2633c.

Figure 5.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of the catalase activity of Rv2663c. The line is the fit of the data by eq 1, which yielded values of kcat = 1475 ± 96 s−1 and Km = 10.1 ± 1.7 mm. Each data point was the average of a minimum of two replicates with error bars shown (R2 = 0.993). (Inset) Visualization of oxygen evolution. Each tube contains 2 ml of 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5. Only the tube on the right contains 10 μm Rv2633c. This picture was taken ∼2 min after addition of 100 mm H2O2 to each tube.

Figure 6.

Kinetic analysis of the inhibition of catalase activity of Rv2366c by cyanide (A) and azide (B). The line is the fit of the data by eq 3. Each data point was the average of a minimum of two replicates with error bars shown. In some cases the error bars are not evident because the values were so similar that the bars are obscured by the data point. The goodness of the fits were R2 = 0.990 for A and R2 = 0.988 for B.

The dependence of the catalase reaction rate on pH was also examined. At pH 8.5, the reaction rate was ∼4-fold less than at pH 7.5. At pH 7.0 there was an increase in the initial rate but the protein was very unstable and it was not possible to get an accurate measurement. At pH 6.5, the protein rapidly precipitated. The internal pH of Mtb was previously determined using pH-sensitive probes, and the basal pH was found to be 7.65 (17). In that study, it was also shown that after an 8 h incubation in buffer at pH 4.5, the internal pH only decreased to 7.2. Thus, the conditions used to determine the kinetic parameters for the catalase activity of Rv2633c approximate the physiological conditions in which the enzyme functions in vivo during normal and stressful conditions.

Rv2633c was also tested for peroxidase activity using a variety of potential co-substrates with H2O2. No peroxidase activity was observed using either ascorbate, pyrogallol or o-dianisidine as an electron donor at concentrations up to 100 mm.

Discussion

Catalases are widespread throughout nature. The vast majority of catalases are iron-containing proteins with the iron present in a heme cofactor (18). Some catalases also exhibit peroxidase activity, such as KatG of Mtb (19). Those bi-functional catalase-peroxidase enzymes are also heme-dependent. There is also a comparatively small family of other catalases, which do not contain heme but instead use two manganese ions in the active site (20). Interestingly, these metals are carboxylate bridged in a structure very similar to the di-iron metal site of hemerythrins, but with manganese rather than iron. However, despite the similarity of the di-metal binding sites, Rv2633c behaves more like a heme-dependent catalase than a manganese catalase with respect to inhibitors. The manganese catalases are relatively insensitive to cyanide and azide, yet Rv2633c is inhibited by these compounds in the micromolar range, as are heme-dependent catalases. This is a consequence of the presence of iron rather than manganese in the hemerythrin-like metal binding active site. Two other well-characterized enzymes, ribonucleotide reductase and methane monooxygenase, have carboxylate bridged di-iron sites similar to that of hemerythrin (21). However, in these enzymes the sites are primarily used to activate O2, rather than for catalase activity. Thus, Rv2633c may be considered a highly unusual and perhaps unprecedented example of a catalase with a non-heme iron active site.

Rv2633c expression is up-regulated in Mtb during macrophage infection. It is common in nature to have an inducible enzyme that is produced in response to high levels of its substrate to supplement the activity of a constitutive enzyme, which reacts with the same substrate. Catalases from different organisms exhibit a wide range of kcat and Km values (22). The other catalase present in Mtb is the bifunctional catalase-peroxidase, katG. That enzyme was reported to exhibit a kcat/Km at pH 7.0 of 1.0 × 106 s−1 (23), compared with the value determined here at pH 7.5 of 1.5 × 105 s−1. Considering that katG has additional physiological roles as a peroxidase, it may be desirable for the inducible Rv2633c not have a significantly higher catalytic efficiency that would deprive katG of its substrate for other reactions. The importance of this inducible catalase activity is highlighted by the fact that Tn insertions inactivating Rv2633c significantly attenuated the growth of Mtb (4). Furthermore, the finding that proteins with significant sequence similarity to Rv2633c are found only in pathogenic and opportunistic strains of Mycobacteria strongly suggests that this protein evolved to confer resistance to the host immune response to infection by Mycobacterial species.

This study of Rv2633c describes a unique catalase activity for a hemerythrin-like protein and its apparent role during infection by Mtb and other related pathogenic Mycobacterial species. In addition to the potential protective role against endogenous and exogenous oxidants, the generation of O2 as a product of its catalase activity could conceivably aid survival within the hypoxic granuloma environment. Future studies should elucidate what particular features of protein structure allow this di-iron center to bind H2O2 rather than O2 and perform a reaction not previously reported for a di-iron hemerythrin-like protein. The finding that the only proteins that have significant overall sequence similarity to Rv2633c are those of other Mycobacterium species also suggests that this protein could serve as a target for novel therapeutics targeting its enzymatic function either directly, or indirectly by inhibition of upstream regulatory pathways.

Experimental procedures

Expression and purification of Rv2633c

For heterologous expression of the Rv2633c protein, the Rv2633c gene was cloned from Mtb and inserted into pET23a vector, which adds a hexa-histidine tag at the C terminus to facilitate purification. Briefly, the pET23a-2633c recombinant expression plasmid was created by FastCloning (24) the Rv2633c gene into the pET-23a(+) vector (Novagen). The Rv2633c gene was PCR amplified from chromosomal DNA purified from Mtb H37Rv using the primers 2633c_pet23_FC-F (5′-gaaataattttgtttaactttaagaaggagatatacatATGAATGCCTACGACGTATTAAAGC-3′) and 2633c_pet23_FC-R (5′-tcagtggtggtggtggtggtgGATGGCCTTCAGGAGGTCTG-3′). The pET vector portion was PCR amplified using the primers pet23_2633c_FC-F (5′-CACCACCACCACCACCACTGA-3′) and pet23_2633c_FC-R (5′-ATGTATATCTCCTTCTTAAAGTTAAACAAAATTATTTCT-3′). Lowercase letters in primer sequences indicate 5′ extensions that are complementary to the vector primers, which are required for restriction enzyme- and ligase-free Fastcloning method. The DNA fragments were combined, digested with DpnI to eliminate parental plasmid DNA, and transformed into E. coli 10-beta (New England Biolabs). Positive clones were identified by PCR screening and confirmed by sequencing. The pET23a-2633c plasmid was then transformed into Rosetta 2 (DE3) E. coli for expression.

Cells were cultured in LB broth with 100 μg/ml ampicillin and 34 μg/ml chloramphenicol, which was supplemented with 440 mg/L FeSO4·7H2O. Cells were induced with 1.0 mm isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside for 3 h at 30 °C. After growth and harvesting, cell extracts were prepared by either sonication or French Press (multiple preparations were studied in this work). The extract was subjected to affinity chromatography using a cobalt affinity resin (HisPur, Thermo Scientific) in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5. The protein was eluted from the column with ∼25 mm imidazole. The purity of the protein was assessed by SDS-PAGE. When necessary, the protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a HiPrep 16/60 Sephacryl S-300 HR column on an AKTA PURE FPLC system (GE Healthcare). This technique was also used to determine its native mass. Chromatography was performed in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer plus 150 mm NaCl at pH 7.5. The flow rate was 0.6 ml/min. The void volume was calculated using blue dextran. Proteins used as molecular weight markers were glutamate dehydrogenase (332 kDa), methylamine dehydrogenase (124 kDa), MauG (42.3 kDa) and amicyanin (11.5 kDa). A plot of the elution volume/void volume versus log molecular weight was used to estimate the mass of Rv2633c.

Metal analysis

Metal analysis was performed using a sector-field ICP-MS (ThermoFisher Element XR) with a Peltier-cooled inlet system (PC3, Elemental Scientific Inc.). Samples were diluted 100 times in ultrapure 1% nitric acid (HNO3) (Fisher Optima) containing 500 ppt indium as an internal standard. Standards were made in ultrapure 1% HNO3 and checked against U.S. Geological Survey Standard Reference Samples (https://bqs.usgs.gov/srs/).3 All elements were determined in medium resolution mode (M/ΔM > 4000) to minimize potential isobaric interferences. The analyzed isotopes included 55Mn, 56Fe, 60Ni, 63Cu, and 66Zn.

Sequence analysis

NCBI Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) sequencing was used to compare the hemerythrin-like domain in Rv2633c to conserved sequences to predict its structure and function (25). NCBI COBALT was used to create a multiple sequence alignment of proteins with sequences most related to Rv2633c. For molecular phylogenetic analysis of Rv2633c from Mtb and its nearest orthologs, the evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the JTT matrix-based model (26). Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7 (27).

Enzymology

Steady-state kinetic studies of catalase activity were performed at 37 °C in 50 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The Rv2633c protein was present at a fixed concentration of 1.0 nm. Reactions were performed in the presence of varied concentrations of H2O2. The reaction rate was determined by monitoring the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm which corresponds to the concentration of H2O2 (ϵ240 = 43.6 m−1cm−1) (28). Data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation (eq 1) where kcat is turnover number for the protein, Km is the Michaelis constant, [S] is H2O2 concentration, [E] is the enzyme concentration and v is the initial reaction rate.

| (1) |

For inhibition studies, the catalase reaction of Rv2633c was performed as described above in the presence of varying concentrations of either NaCN or NaN3. The reactions were initiated by the addition of 10 mm H2O2. IC50 values were determined empirically from the decrease in initial rate at increasing concentrations of inhibitor. The Ki for each inhibitor was then determined using eq 2. Alternatively, the data were fit by eq 3 for analysis of tight binding inhibitors (29, 30). In these equations [E] is the total enzyme present, S is H2O2, I is the inhibitor, Vo is the rate in the absence of inhibitor and vi is the rate in the presence of each concentration of inhibitor.

| (2) |

| (3) |

To test for peroxidase activity the same buffer and Rv2633c concentration was used. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 10 mm H2O2 in the presence of potential peroxidase substrates. Possible peroxidase activity was monitored spectrophotometrically by an increase at 460 nm for o-dianisidine, an increase at 318 nm for pyrogallol, or a decrease at 290 nm for ascorbate.

Author contributions

Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., K. H. R., W. T. S., and V. L. D. conceptualization; Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., and W. T. S. formal analysis; Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., E. S., K. H. R., W. T. S., and V. L. D. investigation; Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., E. S., K. H. R., and W. T. S. methodology; Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., K. H. R., W. T. S., and V. L. D. writing-original draft; Z. M., K. T. S., M. D. C., E. S., K. H. R., W. T. S., and V. L. D. writing-review and editing; K. H. R., W. T. S., and V. L. D. funding acquisition; W. T. S. and V. L. D. supervision; V. L. D. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sandra Geden for construction of plasmids for expression of recombinant Rv2633c and Dr. Alan M. Shiller for performing the metal analysis at the Division of Marine Science, The University of Southern Mississippi, Stennis Space Center, Mississippi 39529.

This research was supported by Startup Funds from the Burnett School of Biomedical Sciences (to K. H. R. and V. L. D). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Fig. S1.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party hosted site.

- BLAST

- Basic Local Alignment Search Tool.

References

- 1. Homolka S., Niemann S., Russell D. G., and Rohde K. H. (2010) Functional genetic diversity among Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex clinical isolates: delineation of conserved core and lineage-specific transcriptomes during intracellular survival. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000988 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rohde K. H., Abramovitch R. B., and Russell D. G. (2007) Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of macrophages: linking bacterial gene expression to environmental cues. Cell Host Microbe 2, 352–364 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abramovitch R. B., Rohde K. H., Hsu F.-F., and Russell D. G. (2011) aprABC: A Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex-specific locus that modulates pH-driven adaptation to the macrophage phagosome. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 678–694 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07601.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sassetti C. M., and Rubin E. J. (2003) Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 12989–12994 10.1073/pnas.2134250100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhat S. A., Singh N., Trivedi A., Kansal P., Gupta P., and Kumar A. (2012) The mechanism of redox sensing in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 53, 1625–1641 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar A., Farhana A., Guidry L., Saini V., Hondalus M., and Steyn A. J. (2011) Redox homeostasis in mycobacteria: the key to tuberculosis control? Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 13, e39 10.1017/S1462399411002079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Newton G. L., and Fahey R. C. (2002) Mycothiol biochemistry. Arch. Microbiol. 178, 388–394 10.1007/s00203-002-0469-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stenkamp R. E. (1994) Dioxygen and hemerythrin. Chem. Rev. 94, 715–726 10.1021/cr00027a008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takagi T., and Cox J. A. (1991) Primary structure of myohemerythrin from the annelid Nereis diversicolor. FEBS Lett. 285, 25–27 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80716-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karlsen O. A., Ramsevik L., Bruseth L. J., Larsen Ø, Brenner A., Berven F. S., Jensen H. B., and Lillehaug J. R. (2005) Characterization of a prokaryotic haemerythrin from the methanotrophic bacterium Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath). FEBS J 272, 2428–2440 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04663.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. French C. E., Bell J. M., and Ward F. B. (2008) Diversity and distribution of hemerythrin-like proteins in prokaryotes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 279, 131–145 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen K. H. C., Chuankhayan P., Wu H.-H., Chen C.-J., Fukuda M., Yu S. S. F., and Chan S. I. (2015) The bacteriohemerythrin from Methylococcus capsulatus (Bath): Crystal structures reveal that Leu114 regulates a water tunnel. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 150, 81–89 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Isaza C. E., Silaghi-Dumitrescu R., Iyer R. B., Kurtz D. M. Jr., and Chan M. K. (2006) Structural basis for O2 sensing by the hemerythrin-like domain of a bacterial chemotaxis protein: substrate tunnel and fluxional N terminus. Biochemistry 45, 9023–9031 10.1021/bi0607812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baert J. L., Britel M., Sautiere P., and Malecha J. (1992) Ovohemerythrin, a major 14-kDa yolk protein distinct from vitellogenin in leech. Eur. J. Biochem. 209, 563–569 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17321.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li X., Tao J., Hu X., Chan J., Xiao J., and Mi K. (2014) A bacterial hemerythrin-like protein MsmHr inhibits the SigF-dependent hydrogen peroxide response in mycobacteria. Front Microbiol. 5, 800 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makris T. M., Chakrabarti M., Münck E., and Lipscomb J. D. (2010) A family of diiron monooxygenases catalyzing amino acid beta-hydroxylation in antibiotic biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 15391–15396 10.1073/pnas.1007953107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vandal O. H., Pierini L. M., Schnappinger D., Nathan C. F., and Ehrt S. (2008) A membrane protein preserves intrabacterial pH in intraphagosomal Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Med. 14, 849–854 10.1038/nm.1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zamocky M., Furtmüller P. G., and Obinger C. (2008) Evolution of catalases from bacteria to humans. Antioxid Redox Signal 10, 1527–1548 10.1089/ars.2008.2046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Singh R., Wiseman B., Deemagarn T., Jha V., Switala J., and Loewen P. C. (2008) Comparative study of catalase-peroxidases (KatGs). Arch Biochem. Biophys. 471, 207–214 10.1016/j.abb.2007.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whittaker J. W. (2012) Non-heme manganese catalase–the ‘other’ catalase. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 525, 111–120 10.1016/j.abb.2011.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Que L., and Dong Y. (1996) Modeling the oxygen activation chemistry of methane monooxygenase and ribonucleotide reductase. Acc Chem. Res. 29, 190–196 10.1021/ar950146g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Switala J., and Loewen P. C. (2002) Diversity of properties among catalases. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 401, 145–154 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00049-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Njuma O. J., Davis I., Ndontsa E. N., Krewall J. R., Liu A., and Goodwin D. C. (2017) Mutual synergy between catalase and peroxidase activities of the bifunctional enzyme KatG is facilitated by electron hole-hopping within the enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 18408–18421 10.1074/jbc.M117.791202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Li C., Wen A., Shen B., Lu J., Huang Y., and Chang Y. (2011) FastCloning: a highly simplified, purification-free, sequence- and ligation-independent PCR cloning method. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 92 10.1186/1472-6750-11-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boratyn G. M., Camacho C., Cooper P. S., Coulouris G., Fong A., Ma N., Madden T. L., Matten W. T., McGinnis S. D., Merezhuk Y., Raytselis Y., Sayers E. W., Tao T., Ye J., and Zaretskaya I. (2013) BLAST: a more efficient report with usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W29–W33 10.1093/nar/gkt282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones D. T., Taylor W. R., and Thornton J. M. (1992) The rapid generation of mutation data matrices from protein sequences. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 8, 275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kumar S., Stecher G., and Tamura K. (2016) MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beers R. F. Jr., and Sizer I. W. (1952) A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cer R. Z., Mudunuri U., Stephens R., and Lebeda F. J. (2009) IC50-to-Ki: a web-based tool for converting IC50 to Ki values for inhibitors of enzyme activity and ligand binding. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W441–W445 10.1093/nar/gkp253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Copeland R. A. (2000) Tight binding inhibitors. in Enzymes: A Practical Introduction to Structure, Mechanism and Data Analysis, 2nd Ed., pp. 305–317, Wiley-VCH, New York [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.