Significance

We provide a randomized test of policy interventions that address barriers to naturalization for low-income immigrants. We find that offering fee vouchers doubles the naturalization application rate among low-income immigrants, but nudges often used by service providers did not increase applications among fee waiver-eligible immigrants below the poverty level. Our results help guide policy efforts to address the problem of low naturalization rates. The current high fees prevent a considerable share of low-income immigrants who desire to become Americans from submitting their applications. Lowering the fees should therefore increase naturalization rates and generate long-run benefits for new Americans and their communities. However, the poorest immigrants face deeper challenges to naturalization that are not easily overcome with the low-cost nudges we tested.

Keywords: naturalization, citizenship, immigration, randomized controlled trial, nudge

Abstract

Citizenship endows legal protections and is associated with economic and social gains for immigrants and their communities. In the United States, however, naturalization rates are relatively low. Yet we lack reliable knowledge as to what constrains immigrants from applying. Drawing on data from a public/private naturalization program in New York, this research provides a randomized controlled study of policy interventions that address these constraints. The study tested two programmatic interventions among low-income immigrants who are eligible for citizenship. The first randomly assigned a voucher that covers the naturalization application fee among immigrants who otherwise would have to pay the full cost of the fee. The second randomly assigned a set of behavioral nudges, similar to outreach efforts used by service providers, among immigrants whose incomes were low enough to qualify them for a federal waiver that eliminates the application fee. Offering the fee voucher increased naturalization application rates by about 41%, suggesting that application fees act as a barrier for low-income immigrants who want to become US citizens. The nudges to encourage the very poor to apply had no discernible effect, indicating the presence of nonfinancial barriers to naturalization.

There are more than 40 million immigrants in the United States today, including about 20 million who have acquired US citizenship through naturalization (1). Naturalization is often seen as an important marker for the integration of immigrants (2–4). In the words of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, who was born in Czechoslovakia and naturalized, US citizenship is “not just a change in legal status but a license to a dream” (5). As ensured in the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, naturalization provides immigrants with virtually the same rights and benefits as native-born citizens, including access to federal jobs, the right to vote, the ability to sponsor family members for visas, access to a US passport to travel freely, and protection from deportation. There could also be economic benefits to naturalization for immigrants and the communities in which they live. Citizenship may increase immigrants’ economic success both in its instrumental advantages—improving labor market access, for example, by signaling to employers greater stability or language skills—and in its psychological ones, namely a deeper sense of security, confidence, and attachment to one’s community (3, 6). Observational research from the United States and other advanced industrial countries has shown that immigrants who naturalize attain higher incomes, better job prospects, and higher rates of home ownership compared with other long-term immigrants who do not naturalize (3, 7–10). Moreover, recent quasi-experimental evidence from Switzerland has shown that naturalization promotes the long-term social and political integration of immigrants (11, 12).

Despite the potential benefits of citizenship for immigrants and local communities, naturalization rates in the United States have seen a marked decline in recent decades. While 64% of legal foreign-born residents were naturalized in 1970, by 2011 the rate was 56% (13). The US naturalization rate is lower than that of other traditional immigrant-receiving countries, such as Australia, Canada, or the United Kingdom, where about 67 to 89% of immigrants are naturalized (14). As highlighted in a recent report by an expert panel of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS), this decline in naturalization has negative implications not only for national income but also for political participation and integration into American society (4).

Although the United States has low rates of naturalization, surveys find that most immigrants want to become a US citizen (15, 16). This paradox—that despite the potential long-term payoffs of citizenship, naturalization remains undersubscribed, even among immigrants who report they want it—has led researchers, policy makers, and immigrant service providers to turn their attention to better understanding the barriers that prevent immigrants from naturalizing. [To be eligible for naturalization, immigrants must be US lawful permanent residents (LPRs), meet continuous residency requirements (typically 5 y), have basic English proficiency, pass the citizenship test, and have a record of good moral character.] Researchers have, with varying levels of success, focused on three individual-level correlates of naturalization: resources, skills, and motivation (2, 17–19). However, sociologists have questioned those results (20) and introduced a notion of “context of reception” (21, 22) to account for differences across host city environments, including how host populations racially categorize their immigrant communities. Researchers have also pointed to other hurdles faced by eligible immigrants who desire citizenship, such as language limitations, lack of information about how to apply, or insufficient resources to navigate the application forms and deal with legal issues that may arise in the application process (16, 23).

Many of these studies, relying on data from censuses and surveys, have had fragile results. As Portes and Curtis conclude in their study seeking to explain differences in naturalization across a wave of Mexican immigrants to the United States in the early 1970s, “Results of our analysis are less noteworthy for their positive than for their negative implications….[There is a] large array of individual characteristics which fail to correlate with citizenship” (ref. 17, p. 369). In their recent comprehensive summary of research on citizenship acquisition, and noting a lack of reliable findings, the NAS expert panel concluded that “Further research is needed to clearly identify the barriers to naturalization” (ref. 4, p. 21).

This study responds to this call by the NAS panel and goes beyond survey and census data to leverage two randomized controlled designs to provide causal evidence on the effects of interventions that address barriers to naturalization. To maximize the external validity of our study, we examine real-world interventions that were designed in the context of a public/private naturalization program in New York to encourage eligible, low-income immigrants who express interest in attaining US citizenship to apply for naturalization. This group of immigrants is typically the target population of interest for interventions by policy makers and service providers to lower barriers to naturalization. It is important to note that our experiments are not designed to reject prior research on naturalization from surveys and censuses but rather to get better causal leverage and uncover mechanisms that encourage interested immigrants to naturalize, controlling for the factors previous researchers identified as barriers.

The first experiment addresses the conjecture that, in the United States, the cost of the citizenship application process is a major barrier for low-income immigrants. Indeed, the fee rose from $60 in 1989 ($120 in 2017 dollars) to $725 in 2017, a sixfold increase in real dollars (24–26). To test if the naturalization fees provide a barrier, we focus on low-income immigrants who would have to pay the naturalization application fee and leverage the random assignment of a voucher that removes the financial barrier and pays for the application fee.

The second experiment tests the effectiveness of a variety of behavioral nudges that are randomly assigned among immigrants whose incomes are low enough to qualify them for a federal fee waiver that eliminates the cost of the application. The nudges mirror existing interventions that are commonly used by immigrant service providers across the United States to encourage and assist motivated immigrants to naturalize. To the best of our knowledge, these interventions have never been systematically tested using methods of random assignment (27). Policy makers and service providers currently lack systematic information to guide their efforts to best assist the immigrant population and address the problem of low naturalization rates.

Immigrants who were interested in naturalization registered for the public/private naturalization program online, by phone, or in person during the registration window between July and September 2016. To register for the program, immigrants had to be LPRs eligible for naturalization, 18 y or older, reside in New York State, and have a household income below 300% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines. (For example, in 2016, the Federal Poverty Guideline was set at an annual income of $11,880 for a family with one person, $16,020 for two persons, and $20,160 for three persons.)

During the registration, two groups of eligible participants were identified. The first group of registrants were low-income LPRs who have a household income between 150% and 300% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines and do not receive means-tested benefits from the government, such as food stamps or cash assistance. These registrants face a significant financial barrier to naturalization because they are low-income but currently have to pay a $725 application fee for naturalization.* Registrants in this group who lived in New York City or neighboring areas where the program was oversubscribed were entered into a lottery to win a voucher that would pay for their naturalization application fee. After the registration ended, the lottery winners were notified by one of the Opportunity Centers (OCs)—community-based organizations contracted by the New York State Office for New Americans—to provide immigration-related services. The OCs provided free application assistance and processed the vouchers by directly paying the cost of the application to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) on behalf of the applicants. The voucher could only be used to pay the application fee. Registrants who did not win the voucher could still receive free application assistance at the OCs and were informed about this during their registration.

The second group of registrants were very low-income LPRs who have a household income below 150% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines or receive means-tested benefits. Either of these characteristics would make them eligible for the federal fee waiver program. All registrants in this group were informed that they were potentially eligible for the federal fee waiver and were encouraged to contact an OC in their area for assistance with their application. Because registrants in this group face no financial barriers to naturalize, a test of a fee voucher is not sensible. Instead, the program tested behavioral nudges that were designed to help these registrants overcome nonfinancial hurdles in navigating the naturalization process (16, 23). To encourage registrants in this group to seek application assistance, the program randomly assigned them to one of five low-cost nudges or to the control group, which received no nudge beyond the initial message about fee waiver eligibility. Nudges were administered after the registration period ended, and, for programmatic reasons, the random assignment was restricted to registrants who lived in New York City and registered for the program in English or Spanish.†

Details about the interventions, samples, design, measures, and statistical analysis can be found in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. All analyses, except when otherwise noted, were registered in a preanalysis plan made available at Evidence in Governance and Politics under Study ID 20170503AC. The Institutional Review Boards at Stanford University (Protocol 34554) and George Mason University (Protocol 849799) approved this research. Informed consent was obtained from each participant as part of the registration process.

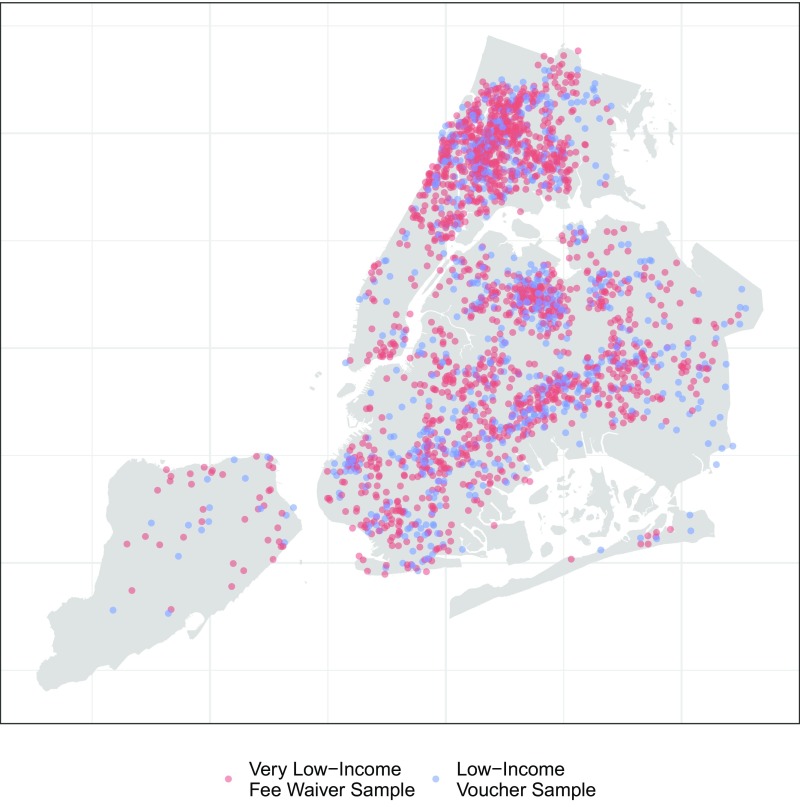

Fig. 1 shows the locations of the registrants in both groups in New York City, where the overwhelming majority of them live. The registrants are distributed across the five boroughs, with 31% in Queens, 30% in the Bronx, 25% in Brooklyn, 12% in Manhattan, and 2% in Staten Island. In the voucher lottery group of low-income LPRs, there were 863 registrants, 336 who won the lottery and were offered a fee voucher and 527 who were not offered a voucher. Registrants in this group had an average annual household income of $19,000 per person, 45% did not obtain a degree beyond high school, and 34% filled out the registration in Spanish (see SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S3). In the group of very low-income LPRs, who were potentially eligible for the federal fee waiver and were randomly assigned to the nudges, there were 1,760 registrants overall. Of those, 1,224 received one of the five nudges, which included a letter from the New York State Office for New Americans reminding them of their potential fee waiver eligibility (n = 399), a similar letter with a MetroCard for free transport to their nearest OC (n = 200), a similar letter and four text Short Message Service (SMS) reminders (n = 400), a call to schedule an appointment at an OC (n = 220), or a mixed-outreach strategy that included multiple such calls, emails, a letter, and a MetroCard worth $10 (n = 25). (See SI Appendix for a detailed description of the five interventions.) The nudges were delivered in English or Spanish, depending on the language preference of the registrants as indicated during registration. The average household income in this group of very low-income registrants was $7,500 per person; 56% had a high school degree or less; and 41% registered in Spanish (see SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). Balance tests support the successful randomization for both the fee vouchers and the nudges (see SI Appendix, Tables S4–S6).

Fig. 1.

Registrants in New York City. Shown are the (jittered) locations of registrants for the public/private naturalization program in New York City (registrants outside this area are not shown to maintain privacy). Red dots indicate the very low-income registrants who were potentially eligible for the federal fee waiver and were randomly assigned to the nudges. Blue dots indicate the low-income registrants who participated in the fee voucher lottery.

To measure the effectiveness of the interventions, a follow-up survey was conducted about 5 mo to 7 mo after the lottery to determine whether the participants had applied for naturalization. The overall response rate for the follow-up survey was 79% (81% for the voucher lottery sample; 78% for the nudge sample), and this rate was balanced across the treatment and control groups in both samples (see SI Appendix, Tables S7 and S8).

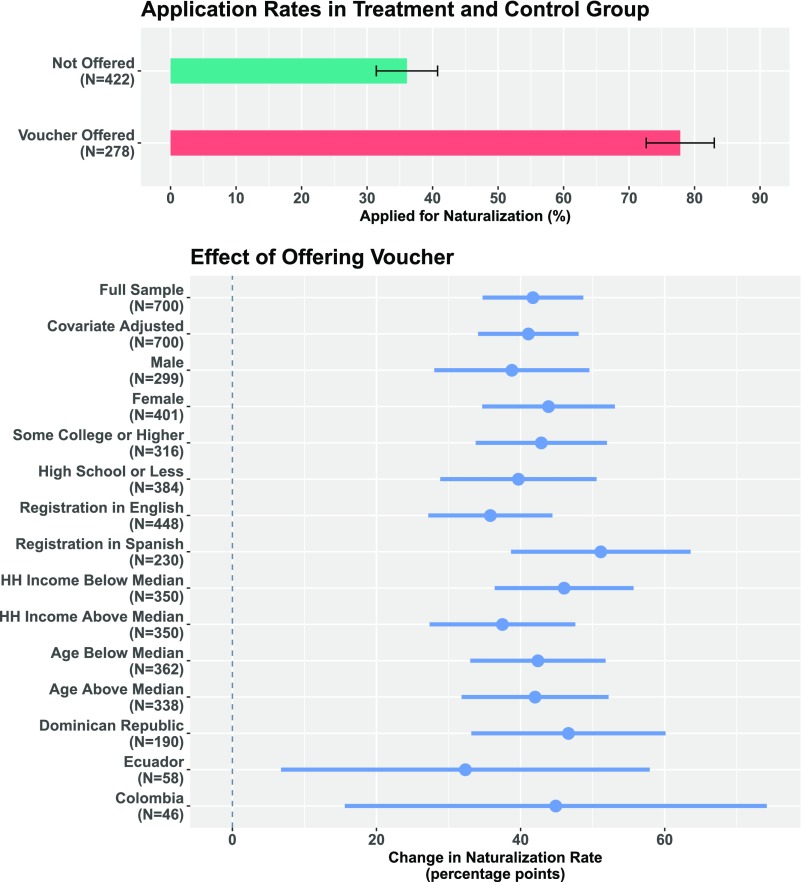

The intention-to-treat effects of the voucher intervention are displayed in Fig. 2. We find that offering the fee voucher substantially increased application rates by about 41% among the low-income LPRs who had registered for the program (P value 0.0001). On average, about 37% of LPRs who were not offered a voucher applied for naturalization, and this rate increased to 78% for LPRs who were offered a voucher. Offering the voucher roughly doubled the rate of naturalization applications.

Fig. 2.

Effects of voucher on naturalization application rates among low-income immigrants. (Upper) The average application rates with robust 95% confidence intervals in the groups of registrants that were offered and not offered the fee voucher to pay for their citizenship application. (Lower) The intention-to-treat effects of offering the fee voucher with robust 95% confidence intervals for the overall study sample and various subgroups defined based on background covariates.

The effect sizes are virtually identical when we adjust for the full set of covariates or use multiple imputation for the missing responses (see SI Appendix, Tables S9 and S15). The effects are also fairly similar across subgroups for gender, age, and education, and for the major origin groups (see SI Appendix, Table S11). The effects are larger, at 46%, for registrants who are below the group’s median household income compared with 37% for those above the median household income, but the difference in effects is not statistically significant at conventional levels (P value = 0.23). Another notable heterogeneity is that the effect of offering the voucher is 51%, from 19% to 70%, for LPRs who registered in Spanish compared with 36%, from 44 to 80%, for those who registered in English (P value = 0.048 for the difference in effects). In nonprespecified analysis, we find that the effects of the fee voucher are similar when we differentiate between registrants who would or would not have been eligible for the new reduced filing fee introduced in December 2016 (see SI Appendix, Table S12).

Overall, given that the fee vouchers substantially increased the naturalization rates, the findings suggest that the financial barrier is a real and binding constraint for low-income LPRs who demonstrated a desire for citizenship and had access to application assistance.

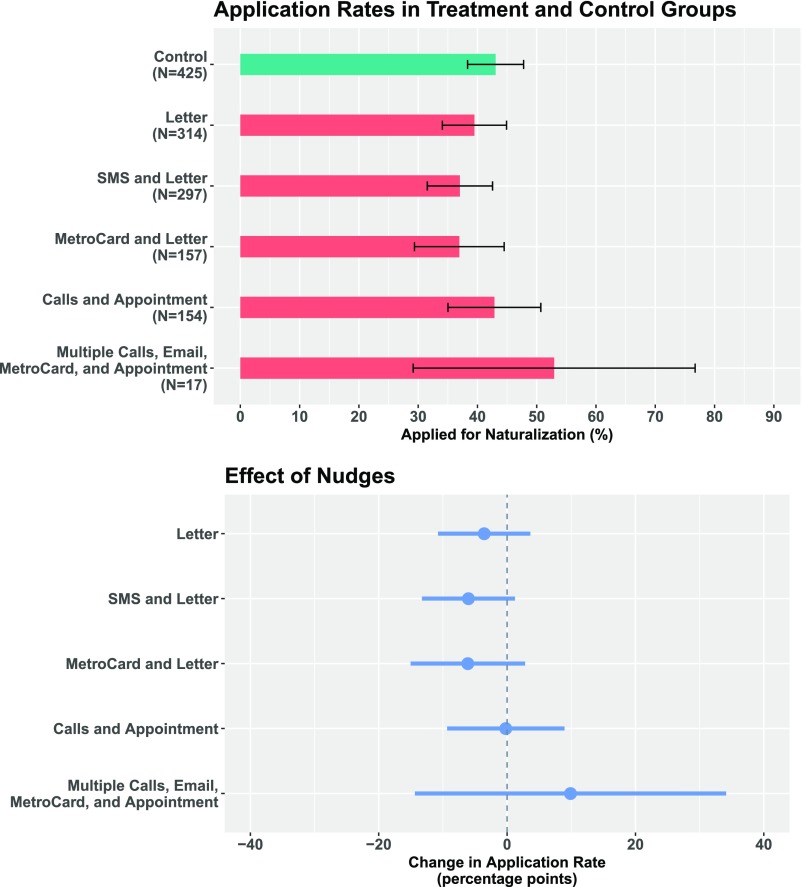

Turning to the second group, very low-income LPRs who qualify for the federal fee waiver, Fig. 3 shows the effects of each of the nudge interventions. Recall that all registrants in this group were informed at registration that they may qualify for the federal fee waiver and were encouraged to visit a nearby OC. Following this registration, 44% of registrants in the control group, who received no additional nudges, applied for naturalization. This application rate may reflect a success of the public/private program, assuming that most registrants in this group of very low-income LPRs would not have applied otherwise, but only learned about their eligibility for the federal fee waiver through the fee waiver eligibility message that all registrants in this sample received from the registration system. That said, the nudge experiment cannot speak to such a potential information effect; it can only speak to whether additional nudges further increased application rates beyond the baseline level observed in the control group.

Fig. 3.

Effects of nudges on naturalization application rates among very low-income immigrants. (Upper) The average application rates with robust 95% confidence intervals in the groups of registrants who received one of the five nudges reminding them of their fee waiver eligibility and encouraging them to apply for naturalization and the control group that received no nudge. (Lower) The intention-to-treat effects of the nudges with robust 95% confidence intervals.

The findings for the nudge experiment in Fig. 3 show that the additional nudges that were built into the public/private program were unsuccessful in raising the application rates beyond the 44% observed in the control group. There are no significant effects for any type of nudge (see SI Appendix, Table S10), including the letter reminding registrants about their fee waiver eligibility and encouraging them to apply (P value = 0.33), a similar letter and four SMS reminders (P value = 0.10), a similar letter and MetroCard (P value = 0.18), a call to schedule an appointment at an OC (P value = 0.97), or a mixed-outreach strategy that combined multiple such calls, emails, a letter, and a MetroCard (P value = 0.42). The results are similar when we control for the full set of covariates or use multiple imputation to address the missing responses (see SI Appendix, Tables S10 and S16).

An initial hypothesis of why the nudges did not work has to do with the time constraints that are faced by the very poor LPRs, often working several jobs or being responsible for young children without support. To examine this issue, we conducted 108 follow-up exploratory interviews (by phone) with a nonrandom sample of participants in the nudge experiment to probe for some of those possible reasons. The reasons for not applying were diverse, but the two most common responses we received were that people were “too busy” or “had difficulty obtaining assistance” with their application. With these self-reports, we went back to our data and found similar null effects for the nudges across a wide variety of subgroups that might be expected to vary in their degree of busyness (e.g., singles versus large households, young versus old) and their difficulty in getting to an OC (e.g., distance) (see SI Appendix, Tables S13 and S14; not prespecified). These results suggest that busyness cannot provide a complete explanation for why the nudges failed, and suggest that there is something more than the busy lives of the poor that constrained additional applications. In sum, although the mixed-outreach strategy intervention had insufficient power to draw a strong inference, overall, the results demonstrate that the nudges, similar to existing interventions used by immigrant service providers, are ineffective in increasing applications above the base rate observed when simply telling registrants about their fee waiver eligibility.

We have provided a randomized controlled study to test the effectiveness of policy interventions to help low-income immigrants overcome barriers to naturalization. To ensure the real-world validity of the research, the study examined interventions that mirrored existing policies and programs and tested them in the New York metropolitan area, which has a high concentration of low-income immigrants. Our results have important implications for theory, research, and policy.

Much of the previous literature focused on country of origin, residency, and other individual-level predictors to explain why some are more likely to naturalize than others (2, 17–19). Instead, our findings from the voucher intervention provide causal evidence supporting the hypothesis that the current high fees prevent a considerable share of low-income immigrants who desire to naturalize from submitting their applications to become Americans (24–26).

The magnitude of the effect of the fee voucher for low-income immigrants is notable given that we only tested the intention-to-treat effect of being offered a voucher and our sample consisted of immigrants who were motivated to naturalize, as they were proactive in registering for the naturalization program.‡ The focus on motivated immigrants was advantageous for the external validity of the study, given that this group of immigrants typically constitutes the target population of interest for policy interventions to reduce barriers to naturalization. That said, it stands to reason that a focus on motivated immigrants resulted in a lower-bound estimate, given that immigrants who did not win the voucher were presumably more likely to naturalize than less motivated LPRs who did not choose to register for the lottery.

Overall, these findings suggest that further reducing naturalization fees for low-income immigrants who do not currently qualify for the fee waiver program would increase the naturalization rate. The findings support USCIS’s rationale for the recent reduction in fees for those with incomes between 150% and 200% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines, but they also suggest that this reduction is insufficient to remove this group’s financial barriers to naturalization.

Moreover, our results imply that many low-income immigrants who do not qualify for the reduced fee, despite their slightly higher incomes, may find the costs forbidding. In particular, for residents earning incomes double the federal poverty threshold, the concurrent 2016 fee increase from $680 to $725 likely acts as an even larger deterrent. To reduce fees for all low-income immigrants while covering the full cost of administrative services, USCIS could introduce a multitiered fee structure in which wealthier applicants pay higher fees. Lowering the financial barrier to naturalization should therefore generate potential long-run benefits for both future new Americans and the communities in which they live.

For the poorest immigrants who wish to naturalize and are eligible for a fee waiver, a set of simple, cheap nudge interventions encouraging them to apply for naturalization did not result in higher application rates. This null finding is important for policy makers and immigrant service providers, given that the nudges we tested are similar to interventions and outreach used by service providers across the United States to encourage poor immigrants to apply for naturalization. To examine why the nudges failed to raise application rates, we conducted follow-up exploratory interviews and then returned to our experimental data. We find that the most common accounts for failure to apply cannot provide a complete explanation for why the nudges failed.

Supported by findings in behavioral economics showing that people’s behavior can be radically shifted with small interventions, nudges have received considerable attention (28–30). However, it stands to reason that, given publication bias (31), failed nudges do not easily find their way into the published literature. This might give policy makers and scientists a biased view of their effectiveness. Obviously, we cannot be sure that other nudges, ones we did not test, would not have been more effective in raising application rates. However, overall, the consistent null results suggest that the poorest immigrants face deeper challenges to naturalization that are not easily overcome with simple fixes like the low-cost and light-touch nudges that were part of the program.

Moreover, the fact that more than half of the very low-income registrants did not apply for naturalization is puzzling and cannot be explained by previous literature that has emphasized a lack of interest (23) or costs (24–26) as reasons to explain why immigrants might not naturalize. The very low-income registrants proactively enrolled in the naturalization program and were informed that they could potentially apply for free, given their fee waiver eligibility; still, more than half did not submit their naturalization application. Other barriers are influential for the poorest immigrants who are interested in naturalization. These barriers could be challenges of time, of information, or of fear in dealing with the law, or other factors that have not been systematically identified in previous research.

Our findings also help delineate where future research is imperative. Although the findings suggest a powerful mechanism for overcoming one hurdle for citizenship—financial barrier—they also point to the presence of other important hurdles, notably among very low-income immigrants. Future research should be devoted to examining what these remaining barriers are and what other interventions might help to overcome them. The null findings for the nudges suggest a clear need for policy makers and service providers to invest in new strategies and incentive schemes to better assist the poorest LPRs who want to become US citizens. Moreover, given that our findings relate to those who demonstrated a desire for citizenship, they leave open the question of how best to encourage immigrants who have not expressed an interest in citizenship. Finally, only having access to application rates, we cannot yet estimate the returns to naturalization. Up until now, evidence on the returns to naturalization exclusively rests on observational studies. Experimental evidence on the economic, social, and political returns to citizenship for both future American citizens and their communities is clearly needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

For program management assistance, we thank Charles Dahan. For research assistance, we thank Madeline Musante, Sara Orton, Valeria Rincon, and Melody Rodriguez. For helpful advice, we thank Veyom Bahl, Shawn Morehead, Laura Gonzalez-Murphy, Monique Francis, Estelle Yessoh, Dominik Hangartner, and Jeremy Weinstein. This research was funded by Robin Hood Grant SPO 123714 and The New York Community Trust Grant P16-000101. We also acknowledge funding from the Ford Foundation for operational support of the Stanford Immigration Policy Lab. The funders had no role in the data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Harvard Dataverse, https://dataverse.harvard.edu (doi:10.7910/DVN/W7MNXK).

*On December 23, 2016, new regulations went into effect that changed the naturalization fee from $680 to $725. These regulations also introduced a new reduced filing fee of $405 for applicants whose household income was between 150% and 200% of the Federal Poverty Guidelines. At the time of the experiment, the fee was still $680, and the voucher covered this amount.

†Only the nudge arm of the study was restricted to registrants who registered using the English and Spanish version of the registration system. Due to resource constraints, it was not possible to administer the nudge calls in all languages. Note that this language restriction only affected a relatively small share of the participants in the nudge arm who registered in Korean (n = 9), Russian (n = 17), and Chinese (n = 82).

‡A few registrants could not be contacted and therefore never received the offer of the voucher. For the intention-to-treat analysis, these registrants are included in the treatment group of those who were “offered” the voucher. This likely leads to an underestimation of the effect of actually receiving the offer of the voucher.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1714254115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Auclair G, Batalova J. Naturalization Trends in the United States. Migration Policy Inst; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang PQ. Explaining immigrant naturalization. Int Migr Rev. 1994;28:449–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organisation for Economic and Co-operative Development . Naturalisation: A Passport for the Better Integration of Immigrants? Org Econ Coop Dev; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . The Integration of Immigrants into American Society. Natl Acad Press; Washington, DC: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall S. May 24, 2012. Madeleine Albright welcomes new citizens, says America needs vitality they bring. ABC News.

- 6.Bloemraad I, Korteweg A, Yurdakul G. Citizenship and immigration: Multiculturalism, assimilation, and challenges to the nation-state. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:153–179. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratsberg B, Ragan JF, Jr, Nasir ZM. The effect of naturalization on wage growth: A panel study of young male immigrants. J Labor Econ. 2002;20:568–597. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bevelander P, et al. The Economics of Citizenship. Malmö Univ; Malmö, Sweden: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pastor M, Scoggins M. Citizen Gain: The Economic Benefits of Naturalization for Immigrants and the Economy. Cent Study Immigrant Integration, Univ Southern Calif; Los Angeles: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enchautegui ME, Giannarelli L. The Economic Impact of Naturalization on Immigrants and Cities. Urban Inst; Washington, DC: 2015. pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hainmueller J, Hangartner D, Pietrantuono G. Naturalization fosters the long-term political integration of immigrants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12651–12656. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418794112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hainmueller J, Hangartner D, Pietrantuono G. Catalyst or crown: Does naturalization promote the long-term social integration of immigrants? Am Polit Sci Rev. 2017;111:256–276. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor P, Gonzalez-Barrera A, Passel JS, Lopez MH. An Awakened Giant: The Hispanic Electorate Is Likely to Double by 2030. Pew Res Cent; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liebig T, et al. Naturalisation: A Passport for the Better Integration of Immigrants? Org Econ Coop Dev; Paris: 2011. pp. 23–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pantoja AD, Gershon SA. Political orientations and naturalization among Latino and Latina immigrants. Social Sci Q. 2006;87:1171–1187. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez-Barrera A, Lopez MH, Passel JS, Taylor P. The Path Not Taken: Two-Thirds of Legal Mexican Immigrants Are Not US Citizens. Pew Res Cent; Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Portes A, Curtis JW. Changing flags: Naturalization and its determinants among Mexican immigrants. Int Migr Rev. 1987;21:352–371. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jasso G, Rosenzweig MR. Family reunification and the immigration multiplier: US immigration law, origin-country conditions, and the reproduction of immigrants. Demography. 1986;23:291–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiswick BR, Miller PW. Citizenship in the United States: The roles of immigrant characteristics and country of origin. In: Constant AF, Tatsiramos K, Zimmerman KF, editors. Ethnicity and Labor Market Outcomes. Emerald Insight; Bingley, UK: 2009. pp. 91–130. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bloemraad I. Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. Univ Calif Press; Berkeley, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Portes A, Rumbaut RG. Legacies: The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Univ Calif Press; Berkeley, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox C, Bloemraad I. Beyond “white by law”: Explaining the gulf in citizenship acquisition between Mexican and European immigrants, 1930. Social Forces. 2015;94:181–207. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeSipio L. Social science literature and the naturalization process. Int Migr Rev. 1987;21:390–405. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sumption M, Flamm S. The Economic Value of Citizenship for Immigrants in the United States. Migration Policy Inst; Washington, DC: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramírez R, Medina O. Catalysts and Barriers to Attaining Citizenship: An Analysis of Ya Es Hora ¡CIUDADANIA! Natl Counc La Raza; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pastor M, Sanchez J, Ortiz R, Scoggins J. Nurturing Naturalization: Could Lowering the Fee Help. Cent Study Immigrant Integration, Univ Southern Calif; Los Angeles: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coddou M. A Case Study in Innovative Partnerships: How Human Services Agencies Can Help Increase Access to U.S. Citizenship. New Am Campaign; San Francisco, CA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pope DG, Price J, Wolfers J. 2013. Awareness Reduces Racial Bias (Natl Bur Econ Res, Cambridge, MA), NBER Work Pap 19765.

- 29.Kahan DM. Gentle Nudges vs. Hard Shoves: Solving the Sticky Norms Problem. Univ Chicago Law Rev; Chicago: 2000. pp. 607–645. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thaler Richard H, Sunstein Cass R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale Univ Press; New Haven, CT: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Franco A, Malhotra N, Simonovits G. Publication bias in the social sciences: Unlocking the file drawer. Science. 2014;345:1502–1505. doi: 10.1126/science.1255484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.