Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a lifelong chronic relapsing transmural inflammatory bowel disease most commonly known to affect any portion of the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus in a skip-lesion fashion. Typical presentation occurs in patients between the ages of 15–30 with fever, abdominal pain, weight loss, and bloody or non-bloody diarrhea.1 In pediatric patients, it may present with growth impairment, failure to thrive, and delayed puberty.2 Common extraintestinal or metastatic manifestations of Crohn’s disease include uveitis, erythema nodosum, and arthritis. Currently, there are few reports of urogenital metastatic Crohn’s disease in the pediatric population. Children who present in the absence of any gastrointestinal symptoms often have difficulties in receiving the correct diagnosis, leading to delayed and/or inappropriate management. The fact that persistent penile swelling is an uncommon pediatric condition, along with its many different etiologies, means it can be difficult for a patient who first presents to be correctly diagnosed with metastatic Crohn’s disease of the genitourinary tract. Increased awareness and reporting of this rare condition can help improve timely diagnosis and appropriate, evidence-based treatment for these patients.

Case report

An eight-year-old male initially presented with tender penile and scrotal swelling, erythema, and fibrosis, without voiding dysfunction. He was afebrile and otherwise clinically well. The patient first presented to his local emergency department in December 2014 and had multiple emergency room visits and hospital admissions for what was originally thought to be recurrent scrotal cellulitis exacerbated by alleged kicks to the area received during an altercation with peers. The patient was treated multiple times with different antibiotics (ceftriaxone, cefazolin, cephalexin, and gentamicin), which had minimal effect in decreasing the swelling and erythema. Initial ultrasound studies suggested bilateral complex abscesses or hydroceles with overlying skin thickening. Eventually, scrotal exploration was performed due to inadequate response to antibiotics and concerns regarding possible testicular torsion. Scrotal exploration demonstrated an edematous and significantly thickened skin with no abscesses and normal testes. The patient was subsequently referred to our centre.

Upon presentation to BC Children’s Hospital in May 2016, the scrotal and circumcised penile skin were tender, erythematous, and thickened, with a dry, crusted surface. There was a 1 cm circumferential subcoronal ring of thick, shiny skin. There was no discharge (Fig. 1). Biopsies of the midline scrotal and penile regions were performed under general anesthesia. Pathology revealed granulomatous dermal lymphangitis with fibrosis (Fig. 2A). The granulomatous inflammation was characterized by loose, non-necrotizing collections of histiocytes and histiocytic giant cells with a peripheral rim of lymphocytes adjacent to dermal lymphatics (Figs. 2B, C). Foreign material was not identified and there was no histological evidence of associated microorganisms, including fungi and acid-fast bacteria.

Fig. 1.

Intraoperative appearance of scrotal and penile edema at time of biopsies.

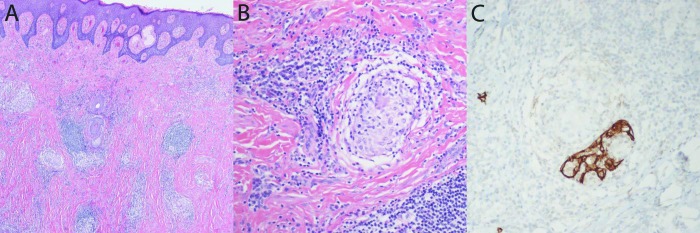

Fig. 2.

Microscopic examination of scrotal tissue reveals dermal granulomatous inflammation centered on vasculature and fibrosis (A; H&E, 40x original magnification). The granulomatous inflammation includes occasional histiocytic giant cells (B; H&E, 200x original magnification) and is centred on dermal lymphatics as highlighted in brown by immunostaining for the lymphatic marker D2-40 (C; 200x original magnification).

The patient subsequently underwent upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy demonstrating ulcers in the stomach and duodenum. Biopsies from these regions, as well as those from the colon and terminal ileum all revealed chronic active granulomatous inflammation consistent with Crohn’s disease. Local treatment with topical steroids and intravenous therapy with the monoclonal antibody biologic drug infliximab was initiated.

Discussion

Currently, the differential diagnosis for recurrent penile swelling in pediatric patients includes trauma, primary and secondary lymphedema, previous penile surgery, infection, and non-specific inflammation (contact dermatitis, bala-noposthitis, peritonitis).3,4 For chronic genital swelling, the differential also includes sarcoidosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, fungal or helminth infections, recurrent erysipelas, or pelvic neoplasms.4

Park et al described the first case of metastatic Crohn’s disease with cutaneous manifestations in a 70-year-old woman.5 This has been more commonly reported in adults with minimal involvement of the urogenital system in both adults and pediatric populations.5 Metastatic Crohn’s disease also has the potential to exist in isolation of intestinal findings. Urogenital manifestations of Crohn’s disease in children include penoscrotal swelling, erythema, plaques, or ulcers in males.6 In females, vulvar swelling, fissures, and ulcers are common urogenital manifestations.7 To date, excluding this report, there are 33 (20 males, 13 females) reports of metastatic Crohn’s disease of the genitourinary tract in the pediatric population. The mean age of presentation was 11 years, with a range of 5–18 years.8 Approximately 20% of adults and children with Crohn’s will have extraintestinal manifestations and 6% of children will first present with extraintestinal Crohn’s.2

A recent review of the literature performed by Rani et al found the most common presentation of metastatic Crohn’s disease in the pediatric population was chronic or recurrent penile and/or scrotal swelling (84%) or scrotal plaques (15%) in boys.8 In females, unilateral or bilateral vulvar swelling were the most common (81%), followed by perivulvular and perianal ulcerations (9%) and perivulvular fissures (9%). Upon further investigations, 60% of these pediatric patients also had associated gastrointestinal symptoms as well.8 Unlike in the adult population, urogenital symptoms commonly precede the primary diagnosis of Crohn’s disease among the pediatric population (73%, 22/33).8 This manifestation of metastatic Crohn’s disease can make appropriate diagnosis difficult.

Granulomatous lymphangitis is the characteristic histopathological presentation of metastatic Crohn’s disease in the penile and scrotal region.3,9–11 Some cases may be associated with dermal fibrosis, as in this case, which is thought to be associated with long-standing disease. Granulomatous lymphangitis is not specific for metastatic Crohn’s disease; however, the histopathological differential diagnosis is short and includes sarcoidosis, foreign body-related inflammation, and infection. In the clinical setting of Crohn’s disease, the finding of penoscrotal granulomatous lymphangitis is diagnostic, but in situations where this is the presenting complaint, additional investigations to exclude other entities in the histopatholgical differential diagnosis may be warranted.

There are currently no treatment guidelines for metastatic Crohn’s disease. Oral, topical, or systemic steroids, as well as azathioprine, mesalamine, cyclosporine, or topical tacrolimus have been used. Biologic agents, such as injectable anti-tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (adalimumab or infliximab) have also shown to display some clinical success. Less commonly used are antibiotics (metronidazole). Surgical management involving excision of urogenital lesions is reserved for refractory disease or cosmetic purposes.3 The most common treatment in reported cases is currently oral or topical steroid (67%) or metronidazole (31%) given with or without steroids.8 In medically treated patients, 12% of them had no improvement, with recurrence occurring in 10% of successfully treated patients.8 A recently published case series of five patients with metastatic Crohn’s disease showed that systemic anti-TNFα biologic agents (adalimumab or infliximab) were the most effective, but responses were varied and frequent relapse was common.4 Two out of the five patients in the study eventually required a combination of anti-TNFα and methotrexate, which demonstrated lasting benefit.4 Circumcision had a high complete resolution rate of 80% and patients on continuous long-term therapy were shown to have complete resolution at followup (nine years).3

Metastatic Crohn’s disease of the genitalia is rare. Appropriate workup and diagnosis are needed to prevent inappropriate therapies and facilitate early management. Early biopsy of genital edema without apparent cause would seem prudent. Case reports and increasing data for different treatment modalities will help elucidate a treatment guideline and raise awareness of this rare condition to allow for timely management.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Dr. Samarasekera has been a speaker for Astellas, Astra Zeneca, and Pfizer. The remaining authors report no competing personal or financial interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:3–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000195385.19268.68. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.MIB.0000195385.19268.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jose FA, Garnett EA, Vittinghoff E, et al. Development of extraintestinal manifestations in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:63–8. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20604. https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.20604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirheydar HS, Friedlander SF, Kaplan GW. Prepubertal male genitourinary metastatic Crohn’s disease: Report of a case and review of literature. J Urol. 2014;83:1165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.11.029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uro-logy.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrick BJ, Tollefson MM, Schoch JJ, et al. Penile and scrotal swelling: An underrecognized presentation of Crohn’s disease. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:172–7. doi: 10.1111/pde.12772. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.12772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park AG, Morson BC, Pegum JS. Crohn’s disease with cutaneous involvement. Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58:241–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmaras I, El-Jabbour J, Pietropaolo N, et al. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: A review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22:1033–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02741.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: A rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:329–32. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rani U, Russell A, Tanaka S, et al. Urogenital manifestations of metastatic Crohn’s disease in children: Case series and review of literature. J Urol. 2016;92:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.02.026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy MJ, Kogan B, Carlson JA. Granulomatous lymphangitis of the scrotum and penis. Report of a case and review of the literature of genital swelling with sarcoidal granulomatous inflammation. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:419–24. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028008419.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028008419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sackett DD, Meshekow JS, Figueroa TE, et al. Isolated penile lymphedema in an adolescent male: a case of metastatic Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Urol. 2012;8:e55–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.03.006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpu-rol.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vricella GJ, Coplen DE, Austin PF, et al. Granulomatous lymphangitis. J Urol. 2013;190:1052–3. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]