Abstract

The methods section of a scientific article often receives the most scrutiny from journal editors, peer reviewers, and skeptical readers because it allows them to judge the validity of the results. The methods section also facilitates critical interpretation of study activities, explains how the study avoided or corrected for bias, details how the data support the answer to the study question, justifies generalizing the findings to other populations, and facilitates comparison with past or future studies. In 2006, the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Programme began collecting and disseminating guidelines for reporting health research studies. In addition, guidelines for reporting public health investigations not classified as research have also been developed. However, regardless of the type of study or scientific report, the methods section should describe certain core elements: the study design; how participants were selected; the study setting; the period of interest; the variables and their definitions used for analysis; the procedures or instruments used to measure exposures, outcomes, and their association; and the analyses. Specific requirements for each study type should be consulted during the project planning phase and again when writing begins. We present requirements for reporting methods for public health activities, including outbreak investigations, public health surveillance programs, prevention and intervention program evaluations, research, surveys, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses.

Keywords: Methods, data collection, research reports, medical writing, editorial policies

“People’s views about contradictory health studies tend to vary depending on their level of science knowledge. An overwhelming majority of those with high science knowledge say studies with findings that conflict with prior research are a sign that understanding of disease prevention is improving (85%). A smaller majority of those with low science knowledge say the same (65%), while 31% say that the research cannot really be trusted because so many studies conflict with each other.”

Pew Research Center, February 2017

Introduction

The methods section of a scientific article often receives the most scrutiny from journal editors, peer reviewers, and skeptical readers. Effective reporting of the methods used in public health research and practice enables readers to judge the validity of the study results and other scientists to repeat the study during efforts to validate the findings. Although word limits for a scientific article can hinder complete reporting, full information can usually be provided in online-only or supplemental appendixes. The methods section also facilitates critical interpretation of study results; explains how the study avoided or corrected for bias in selecting participants, measuring exposures and outcomes, and estimating associations between exposures and outcomes; and explains how the data support the answer to the study question. The methods justify generalizing the findings from the sample studied to the population it represents. Finally, complete reporting of methods facilitates comparing the study findings with past and in future studies (e.g., in systematic reviews or meta-analyses).

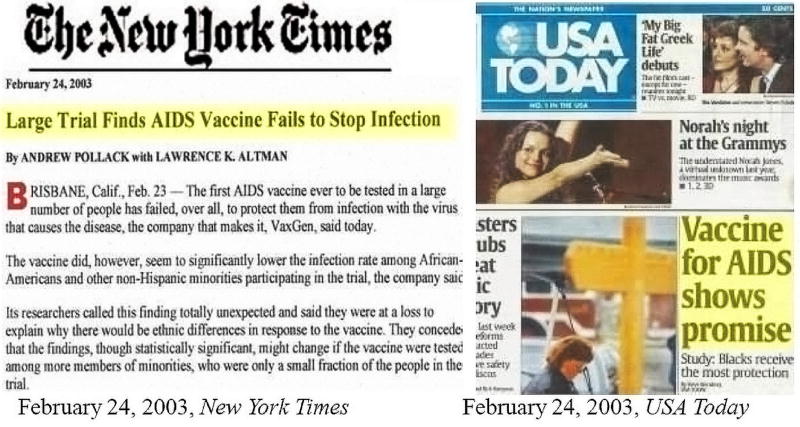

For example, consider two different conclusions from the same study (1) highlighted in two newspaper headlines (Figure 1). A reader must carefully read the methods section of the original study report (not those of newspaper reports) to assess the validity of each headline. Although the vaccine seemed to substantially lower the infection rate among African Americans and other non-Hispanic minorities in the trial, the numbers of participants from these racial/ ethnic groups were too small to support statistically significant conclusions about vaccine efficacy. This “no effect” conclusion is the more valid one, given details in the study methods.

Figure 1.

Differences in media interpretation of a single study.

The methods section is usually the easiest and often the first section of the manuscript to be written, often during the protocol development or study-planning phase, then revised and updated after completion of the study to describe what was actually done during the study, including documentation of any changes from initial protocol. Describing the methods completely in the methods section for all aspects of the study is crucial; the readers should not discover something about the methods buried in the results or discussion. Of note, publishers typically specify their requirements for the methods sections in their journals, and those specifications might be beyond those presented here; therefore, reviewing the publisher’s instructions to authors thoroughly before writing begins is always advisable.

This article provides practical guidance for improving the clarity and completeness of the methods section of a scientific article or technical report. We provide a framework based on published standards for reporting the findings of public health research and practice according to major categories of public health activities. This is not a guide for conducting research. Instead, it describes the essential content of the methods section of a scientific article or technical report. Further, we restrict our attention to public health research and practice, excluding laboratory studies. Finally, we mention important ethical considerations and statistical methods only briefly; details of these topics can be found in “Research and Publication Ethics” and “Reporting Statistical Methods and Results” elsewhere in this issue of the Journal.

Guidelines for reporting public health investigation methods

Reporting guidelines have been developed for many types of public health investigations. Recognizing the proliferation of such guidelines, the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Programme began in 2006 to collect and disseminate guidelines for reporting health research studies (Table S1) (2). We highlight example guidelines that are internationally recognized publishing standards and also include guidelines for reporting methods associated with fundamental public health investigations not classified as research (Table S1).

Disease outbreak investigations

Investigating an outbreak or unexpected increase in the incidence of disease cases or a condition for a geographic area or period is a fundamental public health activity. The primary purpose of an outbreak investigation is to identify the source of the pathogen, its transmission mode (route), and modifiable risk factors for illness so that the most appropriate control and prevention activities can be implemented (3). However, subsequent publication of a scientific report summarizing detection, investigation, and control of the outbreak is useful for disseminating knowledge of new risk factors, investigation techniques, and effective interventions.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has developed a guide for reporting the investigation and findings of disease outbreaks (4). Their guidance recommends reporting of overview or background data (dates of first case and of investigation initiation and conclusion), and methods for case finding and data collection, case investigation, epidemiologic and statistical analysis, and interventions. When a disease outbreak involves a particular setting (e.g., infections acquired in hospitals or related facilities), the reporting guidelines recommend describing the study design, participants, setting, interventions, details of any laboratory diagnosis of the pathogen by culturing and typing, health outcomes, economic outcomes, potential threats to validity, sample size, and statistical methods (5).

Public health surveillance activities

Public health surveillance—the continuous, systematic collection, analysis, and interpretation of health-related data needed to plan, implement, and evaluate public health practice—is another fundamental public health activity (6). Publishing the results of surveillance activities is an essential part of public health action; therefore, the methods section of a surveillance report should include the following:

-

❖

Any legal mandates for data reporting;

-

❖

The methods used for data collection;

-

❖

The methods used for data transfer, management, and storage;

-

❖

Relevant case definitions for confirmed, probable, and suspected

-

❖

The performance attributes of the surveillance system.

These performance attributes of a surveillance system are defined in the Surveillance Evaluation Guidelines, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (United States) (7) and in Principles and Practice of Public Health Surveillance (8).

Intervention and prevention program evaluation

Another fundamental public health activity is evaluating intervention and prevention programs. A framework for program evaluation developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention summarizes key elements of the activity, specifies steps in the process, provides standards for measuring effectiveness, and clarifies the purposes of program evaluation (9). Guidelines for writing the methods section of a program evaluation paper exist for different types of evaluation designs. For example, the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) checklist is useful for reporting evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions with nonrandomized designs (10). The TREND checklist includes advice regarding how the methods should describe the participants, interventions, objectives, outcomes, sample size, exposure assignment, blinding (masking) of investigators or participant exposure, unit of analysis, and statistical methods. In contrast, for reporting the evaluation of interventions to change behavior, recommendations from the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) are more appropriate (11).

When randomization assignment is impractical, evaluations use observational designs and collect information on variables needed at the analysis stage of the investigation to correct for selection bias. Guidelines for reporting observational evaluations consider the observation method, the intervention and expected outcome, study design, information regarding the sample, measurement instruments, data quality control, and analysis methods (12).

Another approach to evaluation is a mixed-method or realist model, a theory-driven evaluation method increasingly used for studying the implementation of complex interventions within health systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (13). Theory-driven evaluation describes the associations between activities and outputs and short- and long-term outcomes. Theory-driven evaluation also attempts to address the problem that evaluations using traditional methods (e.g., experimental and quasi-experimental methods) do not always deal with intervention complexity. For example, in evaluating the effectiveness of community health workers in achieving improved maternal and child health outcomes in Nigeria, researchers chose a theory-driven approach because of countrywide and community-specific factors affecting the outcomes (14). As for other types of evaluation, reporting standards for realist evaluations include describing the reasons for using the method, the environment surrounding the evaluation, the program evaluated, the evaluation design, the data collection methods, the recruitment and sampling, and any statistical analysis (15,16).

If economic factors are important in the evaluation, specific guidelines should be consulted (e.g., the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards or CHEERS) (17). In using these reporting guidelines, some fundamental approaches in evaluation become important. Three approaches are commonly used to establish the effectiveness of a program or intervention: (I) comparing participants in the program with nonparticipants; (II) comparing results from different evaluations, each of which used different methods; and (III) case studies of programs and outcomes. In the comparison approach, random assignment of persons, facilities, or communities can be used to minimize selection bias. However, random assignment can be impractical for interventions involving, for example, mass media programs designed to reach the entire population. In such cases, other methods of assignment to intervention or control groups can be used.

Blinding the investigators and participants to whether a participant is assigned to an intervention or control group can help to avoid measurement bias. A participant’s knowledge that he or she is receiving an intervention can affect the outcome (the Hawthorne effect). The potential for bias is even more likely if the outcome of interest is behavioral, rather than biologic.

Furthermore, measurers of the outcomes must also be blind to what the recipients received to avoid biases in measurement associated with the measurers’ expectations (i.e., double-blinding). However, in certain evaluations, double-blinding is impractical. For example, a breastfeeding mother will be aware that she and her infant are in the breastfeeding intervention group, and that knowledge can affect other aspects of her behavior toward her infant. In such studies, rather than using double-blinding, the investigator might develop placebo interventions that expose mothers to the same amount and intensity of an educational intervention, but on a subject unrelated to breastfeeding (18). Participants and evaluators can be blinded by keeping treatment and control groups physically separate so that members of each group are unaware of the other group’s activities. However, the two groups would then have different experiences with interventions, exposures, and outcomes, presenting challenges for standardizing measures and development of appropriate informed consent procedures.

Public health research

Historically, many of the guidelines for reporting were developed in the context of clinical research studies. One of the earliest of these guidelines is for randomized controlled trials (19). These guidelines and subsequent extensions (20) formed the basis of much of the guideline development discussed in this paper. For each of these research designs, reporting of the methods should discuss how human participants were protected from harm caused by ethics errors, including informed consent, and how participants’ privacy and confidentiality was protected. These methods are covered in more detail in “Research and Publication Ethics” elsewhere in this issue of the Journal.

Clinical case-series reports

A report on a single case of a series of clinical cases with point-of-care data provides evidence of the effectiveness of high-quality patient care and approaches to treating rare or unusual conditions. To help reduce reporting bias, increase transparency, and provide early signals of what interventions work, depending on patient characteristics and circumstances, an international group of experts developed the CARE guidelines for reporting case studies and case-series (21). Even if such a report does not have a designated methods section, it should include information regarding patient characteristics, clinical findings, timelines (e.g., timeline graphs or epidemiologic curves), diagnostic assessments, therapeutic interventions, and outcomes.

Qualitative research

Many health problems can be addressed by combining interdisciplinary quantitative and qualitative methods. In such investigations, qualitative methods can be helpful by providing information about the meaning of text, images, and experiences and how the context surrounding study participants and their environments influence the concepts and theories being studied. For example, to investigate maternal knowledge of and attitudes toward childhood vaccination in Haiti, researchers used focus group discussions, physician observation, and semi-structured interviews with health providers (22). The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (23) checklist includes a qualitative research model, researcher characteristics, context, sampling strategy, ethics protections, data collection (e.g., methods, instruments, and technology), units of study, data processing and analysis, and techniques to enhance trustworthiness. A later extension (Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ) (24) further defined the evaluation domains and added information about the research team.

Cross-sectional surveys and disease registry studies

If a controlled experiment or a quasi-experimental study design is impractical, an observational study is the only research option. The STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) initiative recommends information that should be included in an accurate and complete report of any of three main observational study designs: cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies (25). For cross-sectional studies, surveys, and registry studies, the checklist includes study design, setting (including periods of recruitment), participants (methods of selection and exclusion criteria), variables (outcomes, exposures, confounders, and effect modifiers), data sources and measurements, efforts to address potential sources of bias, study size (including power calculation), quantitative variables and any groupings, and statistical methods (including handling of missing data and sensitivity analysis). The STROBE checklist does not include some important survey methods, such as nonresponse analysis, details of strategies used to increase response rates (e.g., multiple contacts or mode of contact of potential participants), and details of measurement methods (e.g., making the instrument available so that readers can consider questionnaire formatting, question framing, or choice of response categories) (26). Guidelines also have been developed for reporting the methods used for Internet-based surveys, the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) (27).

Use of routinely collected health data, obtained for administrative and clinical purposes rather than research, is increasing in public health. To respond, guidelines for reporting methods used in registry studies were developed in 2015: the REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) checklist (28).

Case-control studies

The case-control study design is useful for determining whether an exposure is directly associated with an outcome (i.e., a disease or condition of interest). This design is often used in public health because it is quick, inexpensive, and easy, compared with a cohort (follow-up) study design, making the case-control study particularly appropriate for (I) investigating outbreaks and (II) studying rare diseases or outcomes. The STROBE guidelines provide specific sections for reporting the methods used for case-control studies. The guidance includes attention to study design, setting, variables, data sources, bias, and study size. Specific to case-control studies is the necessity of reporting eligibility criteria, the sources and methods of case-patient ascertainment and control subject selection, and the rationale for the choice of case-patients versus control subjects. For matched case-control studies, reporting should include the matching criteria and the number of control subjects per case. In this study design, the methods must report how the statistical methods accounted for the matching.

A useful example of reporting methods for case-control studies can be found in “Reporting Participation in Case- Control Studies” by Olson et al. (readers should consider using the tables in that paper) (29). The effect size provides an estimate of the average difference, measured in standard deviation units so as to be scale independent, between a case’s score and the score of a randomly chosen member of the control population. Specific guidance for reporting effect sizes in case-control research is available (30).

Cohort studies

The general guidance of STROBE also is useful for reporting methods used in cohort studies. The adaptations for this study design include reporting methods for determining eligibility criteria, sources and methods of participant selection, and follow-up methods. For matched cohort studies, reporting should include the matching criteria used and the number of participants exposed and unexposed to the hypothesized cause of the outcome; in this case, the methods section also should describe how loss to follow-up was addressed. An example of reporting according to STROBE guidelines for cohort studies is available in Kunutsor et al.’s investigation of the association of baseline serum magnesium concentrations associated with a risk for incident fractures (31).

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Meta-analysis is a statistical procedure for combining data from multiple studies, obtained through a systematic review of the literature. This can be used to identify a common effect (when the treatment effect is consistent among studies), to identify reasons for variation, or to assess important group differences. Pharmaceutical companies use meta-analyses to gain approval for new drugs, with regulatory agencies sometimes requiring a meta-analysis as part of the approval process. Researchers use meta-analyses to determine which interventions work and which ones work best. Many journals encourage researchers to submit systematic reviews and meta-analyses that summarize the body of evidence regarding a specific question, and systematic reviews are replacing the traditional narrative review. Meta-analyses can play a key role in planning new studies by identifying unanswered questions. Finally, meta-analyses can be used in grant applications to justify the need for a new study.

The earliest guideline for reporting meta-analyses was for meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials (32) and specified reporting of searches, selection, validity assessment, data abstraction, study characteristics, and quantitative data synthesis, and in the results with “trial flow,” study characteristics, and quantitative data synthesis. Research documentation was identified for only 8 of 18 items. Subsequently, this guidance was revised and expanded in the PRISMA Statement (33).

With the proliferation of meta-analyses of observational studies, reporting guidance followed (34). The MOOSE Statement requires a quantitative summary of the data; the degree to which coding of data from the articles was specified and objective; an assessment of confounding, study quality, and heterogeneity; the statistical methods used; and display of results (e.g., forest plots). The PRISMA statement also includes recommendations useful for reporting meta-analyses of observational studies; thus, both checklists should be consulted. Several extensions of the PRISMA checklist are available for network meta-analyses, health equity, and complex interventions (35).

Summary

The methods section of a scientific article must persuade readers that the study design, data collection, and analysis were appropriate for answering the study question and that the results are accurate and trustworthy. The methods section is often written first and is the easiest section of the manuscript to write because it is often written before the study begins. Writers should report the methods that were actually used in addition to methods that were planned but not used. Regardless of the type of study conducted and type of document written, the methods section should include certain core descriptive elements: the study design, how participants were selected, the setting, the period of interest, the variables and their definitions used for analysis, the procedures or instruments used to measure exposures, outcomes, and their association, and the analyses that produced the data that answer the study question. These core elements are common across all study designs, and the specific requirements for each study type should be consulted during project planning and again when writing begins.

Care should be taken to ensure that all methods are described in the main methods section or in supplementary online material, and not included in the results or discussion. Careful attention to reporting of methods can assist journal peer reviewers and readers, as well as other researchers who might use the methods to replicate the study or use the results in a meta-analysis or systematic review.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tom Lang for very helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Footnotes

Contributions: (I) Conception and design: All authors; (II) Administrative support: DF Stroup, CK Smith; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: All authors; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: DF Stroup, CK Smith; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: All authors; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Cohen J. AIDS vaccine trial produces disappointment and confusion. Science. 2003;299:1290–1. doi: 10.1126/science.299.5611.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.EQUATOR Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research. Available online: https://www.equator-network.org/

- 3.Desenclos JC, Vaillant V, Delarocque Astagneau E, et al. Principles of an outbreak investigation in public health practice. Med Mal Infect. 2007;37:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Outbreak reporting guide -CCDR. 2015 Apr 2;41-04 doi: 10.14745/ccdr.v41i04a02. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/canada-communicable-disease-report-ccdr/monthly-issue/2015-41/ccdr-volume-41-04-april-2-2015/ccdr-volume-41-04-april-2-2015-1.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stone SP, Kibbler CC, Cookson BD, et al. The ORION statement: guidelines for transparent reporting of outbreak reports and intervention studies of nosocomial infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:282–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. Health topics: public health surveillance. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/topics/public_health_surveillance/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.German RR, Lee LM, Horan JM, et al. Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems: recommendations from the Guidelines Working Group. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50:1–35. quiz CE1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Groseclose SL, German RB, Nsbuga P. Chapter 8. Evaluating public health surveillance. In: Lee LM, Teutsch SM, Thacker SB, et al., editors. Principles and practice of public health surveillance. 3. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 166–97. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A framework for program evaluation. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2017. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/eval/framework/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, et al. Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:361–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott SD, Albrecht L, O’Leary K, et al. Systematic review of knowledge translation strategies in the allied health professions. Implement Sci. 2012;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portell M, Anguera MT, Chacón-Moscoso S, et al. Guidelines for reporting evaluations based on observational methodology. Psicothema. 2015;27:283–9. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2014.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. London: Sage Publications Limited; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirzoev T, Etiaba E, Ebenso B, et al. Study protocol: realist evaluation of effectiveness and sustainability of a community health workers programme in improving maternal and child health in Nigeria. Implement Sci. 2016;11:83. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0443-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong G, Westhorp G, Manzano A, et al. RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC Med. 2016;14:96. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0643-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.University of Oxford/Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences. The RAMESES projects. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 2013. Available online: http://www.ramesesproject.org/Home_Page.php. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS)—explanation and elaboration: a report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2013;16:231–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer MS, Guo T, Platt RW, et al. Infant growth and health outcomes associated with 3 compared with 6 mo of exclusive breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:291–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet. 2001;357:1191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The CONSORT Group. The CONSORT extensions. Ottawa, ON: The CONSORT Group; Available online: http://www.consort-statement.org/extensions. [Google Scholar]

- 21.The CARE Group. CARE case report guidelines. Oxford, UK: The Care Group; Available online: http://www.care-statement.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudelson PM. Qualitative research for health programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1994. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/62315/1/WHO_MNH_PSF_94.3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med. 2014;89:1245–51. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS Med. 2010;8:e1001069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) J Med Internet Res. 2004;6:e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely-collected health Data (RECORD) Statement. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olson SH, Voigt LF, Begg CB, et al. Reporting participation in case-control studies. Epidemiology. 2002;13:123–6. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200203000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crawford JR, Garthwaite PH, Porter S. Point and interval estimates of effect sizes for the case-controls design in neuropsychology: rationale, methods, implementations, and proposed reporting standards. Cogn Neuropsychol. 2010;27:245–60. doi: 10.1080/02643294.2010.513967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, et al. Low serum magnesium levels are associated with increased risk of fractures: a long-term prospective cohort study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:593–603. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0242-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet. 1999;354:1896–900. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.University of Oxford. PRISMA: transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses; extensions. Oxford, UK: University of Oxford; 2015. Available online: http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/Default.aspx. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.