Abstract

Clopidogrel (Plavix®), is a widely used antiplatelet agent, which shows high inter-individual variability in treatment response in patients following the standard dosing regimen. In this study, a physiology-directed population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) model was developed based on clopidogrel and clopidogrel active metabolite (clop-AM) data from the PAPI and the PGXB2B studies using a step-wise approach in NONMEM (version 7.2). The developed model characterized the in vivo disposition of clopidogrel, its bioactivation into clop-AM in the liver and subsequent platelet aggregation inhibition in the systemic circulation reasonably well. It further allowed the identification of covariates that significantly impact clopidogrel’s dose–concentration–response relationship. In particular, CYP2C19 intermediate and poor metabolizers converted 26.2% and 39.5% less clopidogrel to clop-AM, respectively, compared to extensive metabolizers. In addition, CES1 G143E mutation carriers have a reduced CES1 activity (82.9%) compared to wild-type subjects, which results in a significant increase in clop-AM formation. An increase in BMI was found to significantly decrease clopidogrel’s bioactivation, whereas increased age was associated with increased platelet reactivity. Our PK/PD model analysis suggests that, in order to optimize clopidogrel dosing on a patient-by-patient basis, all of these factors have to be considered simultaneously, e.g. by using quantitative clinical pharmacology tools.

Keywords: Clopidogrel, Physiology-directed population, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model, Pharmacogenetics, CYP2C19, CES1, PK/PD modeling

1. Introduction

Clopidogrel (Plavix®), a second generation thienopyridine platelet inhibitor, has been the standard-of-care for treating patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and/or undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in recent years (Wright et al., 2011). Although clopidogrel is generally considered safe and effective, considerable variability in treatment response has been reported for many patients (Perry and Shuldiner, 2013). It is thought that approximately 20–44% of patients receiving the standard clopidogrel dosing regimen (300 mg loading dose, 75 mg maintenance dose) do not receive the full treatment benefit, which results in high on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR) and continued cardiovascular events (Angiolillo et al., 2007; Geisler et al., 2008; Gurbel et al., 2003; Gurbel and Tantry, 2007; Matetzky et al., 2004; Taubert et al., 2006). On the other hand, some patients also experience drug-induced bleeding due to excessive platelet inhibition (Yusuf et al., 2001).

Clopidogrel itself is an inactive pro-drug that requires enzymatic conversion into its active metabolite (clop-AM) by a number of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes (Kazui et al., 2010; Patrono, 2009). Once formed, clop-AM binds irreversibly to the P2Y12 receptor, which is located on the surface of platelets, where it inhibits platelet aggregation and decreases platelet reactivity for the platelet’s life span. Following oral administration, about 50% of the clopidogrel dose is absorbed from the gut prior to entering the liver (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011), where the drug undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism. Most of the drug (85–90%) is hydrolyzed by liver-specific carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive carboxylic acid metabolite SR26334 (Bonello et al., 2010), while the remainder is converted to the active metabolite R-130964 (clop-AM) in a two-step bioactivation process (Kazui et al., 2010). It should be noted that in addition to the breakdown of clopidogrel, CES1 is also involved in the metabolism of clopidogrel’s intermediate and active metabolites in the liver (Bouman et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2013). As a result, only about 2% of the administered clopidogrel dose reaches the systemic circulation where it becomes available for exerting its pharmacological effect (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011).

In vitro enzyme kinetic data using cDNA-expressed human P450 isoforms suggests that CYP1A2 (35.8%), CYP2B6 (19.4%) and CYP2C19 (44.9%) contribute to the formation of 2-oxo-clopidogrel, whereas CYP2B6 (32.9%), CYP2C9 (6.79%), CYP2C19 (20.6%) and CYP3A4 (39.8%) contribute to the formation of clop-AM, respectively (Kazui et al., 2010), suggesting that CYP2C19 is responsible for about 50% of the overall clop-AM formation. Polymorphisms in the gene encoding for CYP2C19 will consequently have a significant impact on clopidogrel’s dose–concentration–response relationship. This is in line with previous literature reports, where CYP2C19 was identified as one of the most important polymorphic CYP enzymes across different populations. Approximately 3–5% of Caucasians and 15–20% of Asians are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers (PMs) with no remaining CYP2C19 functionality (Desta et al., 2002). The importance of CYP2C19 on clopidogrel treatment effect has been confirmed by numerous clinical studies, which show that patients with decreased CYP2C19 activity, i.e. intermediate metabolizers (IMs) or PMs, have remarkably higher on-treatment platelet reactivity and, thus, an increased risk in experiencing ischemic events following administration of the standard dosing regimen. As a consequence, FDA issued a boxed warning for patients with decreased CYP2C19 activity (FDA, 2010; Hochholzer et al., 2010; Shuldiner et al., 2009; Siller-Matula et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2009). Several clinical studies also revealed that, in addition to CYP2C19 polymorphism, multiple other demographic and disease-related risk factors contribute to the between-subject variability in clopidogrel treatment response (Frelinger et al., 2013; Hulot et al., 2006; Mega et al., 2009; Siller-Matula et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2009). For example, age was identified as covariate in older ACS patients, who have significantly higher on-treatment platelet reactivity than their younger peers (Cuisset et al., 2011; Hochholzer et al., 2010; Shuldiner et al., 2009). It has also been shown that obesity significantly affects the response to clopidogrel treatment as a result of lower systemic exposure to clop-AM and, thus, reduced platelet inhibition (Shuldiner et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2013). Diabetes mellitus leads to significantly higher on-treatment platelet reactivity (Hochholzer et al., 2010) at least partially due to the suppressions of CYP2C19 activity and, thus, lower systemic clop-AM exposure (Bogman et al., 2010; Erlinge et al., 2008). Findings from recent in vitro studies further suggest that changes in CES1 activity also greatly impact clopidogrel’s dose–concentration–response relationship (Zhu et al., 2013). These findings were confirmed in healthy adults and patients undergoing PCI, who were carriers of CES1 loss-of-function alleles (Lewis et al., 2013b). In order to appropriately account for inter-individual differences in response to clopidogrel treatment, all of these factors as well as their dynamic interplay have to be accounted for simultaneously, which is difficult if not impossible to achieve in head-to-head clinical trial settings. This challenge may be met by the use of modeling and simulation approaches as they allow for the integration of data from different in vitro, animal and clinical data into a single unifying model (Jiang et al., 2015). Once established and qualified, this model can then be used to explore clinically yet unstudied scenarios or combinations of different covariates and thus guide dose selection as well as the design of future clinical trials.

The objective of this study was to develop a physiology-directed population pharmacokinetic pharmacodynamic (pop-PK/PD) modeling and simulation framework using data from the Pharmacogenomics of Anti-platelet Intervention (PAPI) and PGXB2B studies that allows to simultaneously evaluate the impact of multiple demographic and genetic factors on clopidogrel’s dose–concentration–response relationship on a physiological rather than a purely descriptive basis. The proposed framework expands on conventional PK/PD approaches as it specifically takes information on the biotransformation site as well as respective physiological parameters into consideration. Its mechanistic nature uniquely positions the developed framework as knowledge platform that can be readily expanded to evaluate the impact of newly identified polymorphisms or covariates to determine their overall impact on platelet reactivity and ultimately to guide dose selection for an individual patient.

2. Methods

2.1. Clinical studies

2.1.1. Amish PAPI study

Study details, recruitment and population characteristics of the Amish PAPI study (NCT0079936) are described elsewhere (Lewis et al., 2013a; Shuldiner et al., 2009). The current analysis utilized an expanded set of 605 healthy male and female Amish Caucasian individuals recruited from August 2006 to January 2011 (Table 1). Briefly, the use of all medications, vitamins and supplements were discontinued 1 week before the initiation of the study. Information on all participants’ medical and family history was obtained. Physical examinations, blood samples, anthropometric measures and extensive phenotypic measurements were conducted after an overnight fast. Following baseline platelet aggregation measurement, all participants were given a 300 mg loading dose of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg maintenance dose per day for 6 days. At one hour following the last clopidogrel dose, a blood sample was drawn, platelet aggregation, clopidogrel and clop-AM concentrations were obtained.

Table 1.

Demographic and pharmacogenetic characteristics of PAPI (N = 605) and PGXB2B (N = 18) subjects assessed in the population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis.

| Baseline characteristics | PGXB2B (N = 18) | PAPI (model estimation) (N = 480) | PAPI (model qualification) (N = 125) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 43 ± 10 | 44 ± 13 | 44 ± 14 |

| Male | 11 | 237 | 64 |

| Weight, kg | 79.8 ± 12.9 | 75.3 ± 12.7 | 74.9 ± 13.8 |

| Height, cm | 169 ± 8 | 167 ± 8 | 167 ± 9 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28.1 ± 4.7 | 27.1 ± 4.6 | 26.8 ± 4.9 |

| CYP2C19*1/*1 | 4 | 145 | 45 |

| CYP2C19*1/*2 | 5 | 103 | 24 |

| CYP2C19*2/*2 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| CYP2C19 *1/*17 | 2 | 147 | 31 |

| CYP2C19 *2/*17 | 1 | 54 | 5 |

| CYP2C19 *17/*17 | 0 | 24 | 13 |

| CES1 CC | 17 | 473 | 125 |

| CES1 TC | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| PON1 AA | 8 | 223 | 61 |

| PON1 AG | 8 | 201 | 52 |

| PON1 GG | 2 | 56 | 12 |

2.1.2. PGXB2B study

Healthy Amish subjects who had participated previously in the PAPI (NCT0079936) study were recruited in the PGXB2B study (NCT01341600). The study details and population characteristics were previously reported (Horenstein et al., 2014). Briefly, of the 18 healthy male and female adults, 6 were CYP2C19 extensive metabolizers (EMs, *1/*1 and *1/*17), 6 were CYP2C19 IMs (*1/*2 and *2/*17), and 6 were CYP2C19 PMs (*2/*2), as shown in Table 1. The use of all medications, vitamins and supplements was discontinued 1 week before the initiation of the study. Information on all participants’ medical and family history was obtained. Physical examinations, blood samples, anthropometric measures and extensive phenotypic measurements were conducted after an overnight fast. All subjects received 75, 150 or 300 mg clopidogrel once daily for 8 days in a crossover study design. Plasma concentrations of clopidogrel and clop-AM were measured at 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h on day 1 after drug administration at each dose. Platelet reactivity was determined at baseline as well as 4 h after drug administration on day 1 and day 8 at each dose. Drug was washed out for one week after each dose treatment.

2.2. Genotyping

Genotyping methods have already been reported in detail (Horenstein et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b; Shuldiner et al., 2009). In brief, genotyping of the CYP2C19*2 (rs4244285), CYP2C19*17 (rs12248560), CES1 G143E (rs71647871) and Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) Q192R (rs662) single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) was conducted using a TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

2.3. Quantification of clopidogrel and clopidogrel active metabolite

Analytical methods for the quantification of clopidogrel and clop-AM were previously reported in detail (Horenstein et al., 2014; Peer et al., 2012). Briefly, blood samples of each participant at each time point (see above) were collected into EDTA tubes containing 2 mmol/L (E)-2-bromo-30-methoxyacetophenone (MPB; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) in order to get a stable clop-AM MPB-derivatized product. Plasma levels of clopidogrel and clop-AM were then measured simultaneously with an ultra-high performance chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) system containing a Waters Acquity UPLC® system (Waters Corporation, Milford, MD) and an AB Sciex Qtrap® 5500 tandem mass spectrometry (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA). The m/z ratios of parent to product ion of clopidogrel, clop-AM and ticlopidine (internal standard) were 322 → 212, 504 → 155, and 264 → 154, respectively. The Multi Quant algorithm from MultiQuant 4.0 (Analyst®, AB Sciex) was used to perform multiple reaction monitoring peak integration and data analyses.

2.4. Platelet aggregation measurements

Assessment of platelet function has been reported previously (Horenstein et al., 2014; Shuldiner et al., 2009). In brief, platelet-rich plasma (200,000 platelets/μL) isolated from blood samples were collected at each time point (see above). Platelet aggregation was determined by light transmission aggregometry (LTA) using a PAP8E Aggregometer (Bio/Data Corporation, Horsham, PA, USA) after stimulation with ADP (20 μmol/L). It was expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA), which represents the maximal percentage change in light transmittance using platelet-poor plasma as a referent.

2.5. Model development

2.5.1. Structural PK model

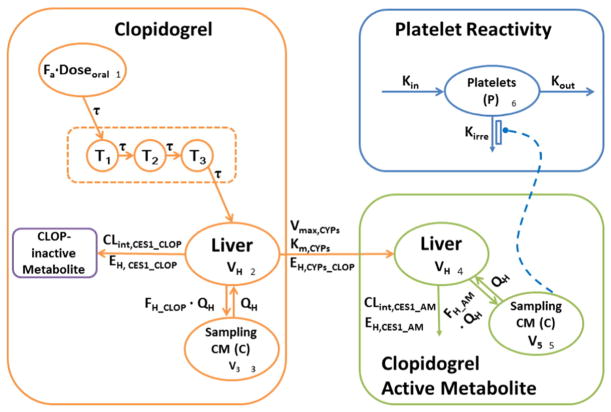

The structural model for the disposition of clopidogrel as well as its active metabolite was based on the metabolic pathways involved in the formation and elimination of clop-AM (Fig. 1). The final model described absorption of clopidogrel (A1) from the gut into the liver (A2), where it undergoes first-pass metabolism by CES1 (EH,CES1) and bioactivation to clop-AM (A4) by CYP enzymes (EH,CYPs). The amounts of clopidogrel and its active metabolite reaching the systemic circulation are denoted by A3 and A5, respectively. Finally, changes in systemic active metabolite concentrations over time are linked to changes in platelet reactivity relative to baseline (A6) to account for the irreversible clop-AM binding to platelet.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the proposed PK/PD model for clopidogrel, its active metabolite (clop-AM) and platelet reactivity (P). Fa: fraction absorbed, T1–T3: transit compartments 1–3, τ: first-order transit rate constant, Clint,CES1_CLOP: intrinsic clearance of clopidogrel mediated by carboxyl esterase 1 (CES1), EH,CES1_CLOP: hepatic extraction ratio of clopidogrel mediated by CES1, Vmax,CYPs: maximum metabolic rate of combined cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes involved in clopidogrel bioactivation, Km,CYPs: Michaelis–Menten constant for combined CYP activity, EH,CYPs_CLOP: hepatic extraction ratio of clopidogrel mediated by CYP enzymes, FH_CLOP: fraction of clopidogrel that escapes first-pass metabolism in the liver and enters the systemic circulation, VH: liver volume, Q H: liver plasma flow, V3: volume of distribution of clopidogrel in systemic compartment, Clint,CES1_AM: intrinsic clearance of clop-AM mediated by CES1, EH,CES1_AM: hepatic extraction ratio of clop-AM by CES1, FH_AM: fraction of clop-AM that escapes first-pass metabolism and enters the systemic circulation, V5: volume of distribution of clop-AM in systemic compartment, kin: zero-order rate constant characterizing platelet formation, kout: first-order rate constant characterizing the natural turnover of platelets, and kirre: second-order rate constant characterizing the clop-AM-mediated inactivation of platelets.

The delay in absorption of clopidogrel from the gut into the systemic circulation following oral drug administration was described by a transit compartment model, where the absorbed fraction (Fa) of the dose of clopdigrel (Dose) travels through 3 transit compartments (Ti) at a first-order rate (τ).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

The amount of clopidogrel in compartment 1 at time zero (A1(0)) was set to Fa · Dose as it represents the dosing compartment. The amount of drug in all other compartments at time zero was set to zero since all drugs (both clopidogrel and clop-AM) that may have been present in the system following previous administration has washed out at the time of first dose (cf. Clinical studies Section).

Once absorbed, clopidogrel is delivered to the liver (A2) via the portal vein, where it undergoes biotransformation. The biotransformation process of clopidogrel in the liver (compartment 2) over time is determined by two competing processes: i) bioactivation of clopidogrel to clop-AM (A4) and ii) metabolic breakdown into inactive metabolites. A well-stirred model (Wilkinson and Shand, 1975) is applied in the current analysis to characterize the hepatic elimination and bioactivation process of clopidogrel, assuming rapid equilibrium in distribution of unbound drugs between blood and hepatocyte cytosol, and rapid equilibrium in drug protein binding both in the blood and in the liver.

| (5) |

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

The formation of clop-AM from clopidogrel is mediated by CYP enzymes (CLint, CYPs_CLOP), which is a saturable process with a maximum metabolic rate (Vmax,CYPs) and the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km,CYPs). The majority of clopidogrel is converted into inactive metabolites by CES1 (CLint, CES1_CLOP), a process that is not saturated at therapeutic clopidogrel dose levels (75 mg to 300 mg) (Jiang et al., 2015). As a result, both CYP- and CES1-mediated biotransformation processes contribute to clopidogrel’s hepatic extraction ratio (EH_CLOP = EH,CES1_CLOP + EH,CYPs_CLOP) and, thus, its hepatic clearance (CLH_CLOP), which is defined as hepatic extraction ratio (EH_CLOP) times hepatic plasma flow (QH). The fraction of clopidogrel that escapes first-pass metabolism in the liver and enters the systemic circulation (FH_CLOP) can consequently be computed according to Eq. (9). The impact of plasma protein binding on clopidogrel pharmacokinetics is also considered during this process. Assuming that clopidogrel exhibits similar protein binding in blood and in the liver, the free fraction of clopidogrel (fu,p_CLOP) was set to 2% in the current model, as derived from literature-reported in vitro protein binding values (98% protein-bound) (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011).

The rate of change in the amounts of clopidogrel in the liver (A2) and systemic circulation (A3) are described by Eqs. (10) and (11),

| (10) |

| (11) |

where A2 and A3 represent the amount of clopidogrel in the liver and the systemic sampling compartment, respectively. VH and V3 represent volume of liver compartment and volume of clopidogrel systemic compartment, respectively.

The well-stirred model (Wilkinson and Shand, 1975) is also applied in the current model to characterize the hepatic elimination of clop-AM. Once clop-AM is formed in the liver, it is either cleared via CES1 (CLint,CES1_AM), as characterized by the hepatic extraction ratio (EH_AM = EH,CES1_AM) and hepatic clearance (CLH_AM), or it enters the systemic circulation (A5). The fraction of clop-AM that escapes first-pass metabolism in the liver and enters the system circulation can be expressed according to Eq. (14). Assuming that clop-AM exhibits similar binding in blood and in the liver, the free fraction of clop-AM (fu,p_AM) was set to 6% based on literature-reported in vitro protein binding values (94% protein-bound) (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011).

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

As a result, the changes in the amount of clop-AM in the liver (A4) or in systemic circulation (A5) over time can be characterized by Eqs. (15) and (16), respectively, where V5 is the volume of distribution of clop-AM in the systemic circulation.

| (15) |

| (16) |

2.5.2. Structural PD model

Once the active metabolite is formed and enters the systemic circulation (A5), it irreversibly binds to the P2Y12 receptor on platelets (A6), which results in platelet inactivation and a decrease in platelet reactivity as expressed by maximal platelet aggregation (MPA) measurement. A modified indirect response model (Dayneka et al., 1993) was set up to characterize the turnover of platelets (A6) and their irreversible inactivation (Eq. (17)),

| (17) |

where the free clop-AM plasma concentrations are calculated by multiplying fu,p_AM with the total systemic concentrations of clop-AM. Respective total clop-AM concentrations are obtained by dividing the amount of clop-AM in the systemic circulation (A5) by systemic distribution volume of clop-AM (V5). In addition, kin is the zero-order rate constant characterizing platelet formation, whereas kout is the first-order rate constant characterizing the natural turnover of platelets and kirre is the second-order rate constant characterizing the clop-AM-mediated inactivation of platelets. Using the baseline level value (MPA0) as a reference, the MPA value following clopidogrel treatment can be computed according to Eq. (18) with A6 (0) = 1.

| (18) |

Once structural model was developed and qualified based on PGXB2B study, the variance as well as the covariance structure of the full PK/PD model was informed by the pooled PK, PD, demographic and pharmacogenetic information from PAPI study and the PGXB2B study.

2.5.3. Variance model

Inter-individual variability (IIV) on fixed effect parameters was modeled using an exponential error model,

| (19) |

Where θT is the population value for parameter θ, θi is the value for this parameter for the ith individual, and ηpi is the random deviation, which is assumed to be normally distributed with a mean of zero and variance of ω2. The difference between observed and model-predicted values was modeled as a combined additive and proportional error model for clopidogrel and clop-AM.

| (20) |

An additive error model was used for platelet reactivity.

| (21) |

In Eqs. (20) and (21), ε1 and ε2 represent the proportional and additive residual errors, with means of zero and variance σ2, between the jth observation in the ith individual (YObs) and its prediction (YPred).

2.5.4. Covariate model

The covariates available for the current PK/PD analysis were listed in Table 1 (Lewis et al., 2011, 2013a, 2013b; Shuldiner et al., 2009) and were included into the model using a forward inclusion and backward elimination procedure (Mandema et al., 1992). The influence of continuous covariates (Covi) normalized to the respective population mean value (CovT; BMIp: 25 kg/m2, agep: 65 years) was modeled by a power function.

| (22) |

The influence of categorical covariates, i.e. CYP2C19 and CES1 polymorphisms, was modeled using Eq. (23),

| (23) |

Where θCov represents the impact of genetic polymorphisms on the maximal velocity (Vmax,CYPs) of CYP2C19 or intrinsic clearance (CLint, CES1) of CES1, respectively. For example, CYP2C19*2 is a nonsense mutation, which results in no expression of the CYP2C19 protein (De Morais et al., 1994) and, thus, a decrease in Vmax value. Given that not all genetic polymorphisms result in phenotypes with clinically significant difference, genotypes were bucketed into three different phenotypes (EMs, IMs, and PMs) for CYP2C19 and CES1 G143E mutation carriers (CES1 TC) or CES1 wild-type subjects (CES1 CC), respectively, as indicated by the superscript for θCov.

Covariates were included into the model if the change in the objective function value (ΔOFV) was larger than 3.84, which corresponds to a p-value of 0.05 assuming a Chi-squared distribution and one degree of freedom (df). Covariates identified during the forward inclusion procedure were retained in the model if the OFV increased by more than 6.64 (p < 0.01, df = 1) when taking the covariate out during the backward elimination procedure. In addition, a reduction in unexplained inter-individual variability and improvement of the standard goodness of fit plots (cf. Model Selection and Qualification section) were also considered for covariate inclusion.

2.6. Model selection and qualification

The selection of the best model was based on standard goodness-of-fit criteria including standard goodness-of-fit plots (observations (DV) versus population predictions (PRED), DV versus individual predictions (IPRED), conditional weighted residuals (CWRES) versus time and CWRES versus PRED), precision of the parameter estimates (i.e., standard errors for fixed and random effects) and ΔOFV using a log-likelihood ratio test. In addition, visual predictive checks (VPCs) were performed for both PGXB2B and PAPI data to test the predictive performance of model. Prediction corrected visual prediction check (PC-VPC) for PGXB2B data was performed using 1000 simulated replicates of the original dataset. Additional VPCs were performed by simulating 500 or 1000 replicates with different age, BMI, CYP2C19 status and their combinations, or with CES1 polymorphism, respectively, using the fixed and random effect parameters of the final model.

2.7. Software

The pop-PK/PD analysis was performed in NONMEM 7.2 (Icon Development Solutions, Ellicott City, MD) using the first-order conditional estimation with interaction (FOCEI) method and the ADVAN 13 subroutine, Pearl-speaks-NONMEM (PsN) (Hasan et al., 2013) tool kit and Pirana 2.7.0b (Hasan et al., 2013). R (http://www.r-project.org), SigmaPlot version 12.3 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) and GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA) were used for graphic model assessment.

3. Results

3.1. Data used in the development and qualification of the PK/PD model

The structural model was developed on the basis of data from seventeen subjects from the PGXB2B study. One subject carrying CYP2C19 *2/*17 mutation was excluded from the development of the structural PK/PD model as this the only individual that carried such CYP2C19 mutation combination in the PGXB2B study. The Km value obtained in this step was fixed during the following full model development step. The final variance and covariate models were developed by simultaneously fitting the pooled data from the PGXB2B study and part of PAPI study (N = 480) that had full PK, PD and covariate information. Data from 125 subjects from PAPI study that has full PD and covariate information but not PK information was used for model qualification (Table 1).

3.2. Population PK/PD analysis

A physiology-directed pop-PK/PD model was developed, which was able to simultaneously characterize dose–concentration–response and covariate relationship following oral administration of clopidogrel (Fig. 1 and Table 2) reasonably well. The structural PK model was based on the known mechanisms involved in the biotransformation of clopidogrel into clop-AM and the elimination of clopidogrel and clop-AM. Fa was fixed at 50% (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011) and its interindividual variability was estimated to be 73.5%. An inter-compartmental transit rate constant (τ) 11.0 1/h was estimated for each of the 3 transit compartments. Liver size and liver plasma flow were fixed to 1.5 L and 50 L/h, respectively, based on literature data (Harrison and Gibaldi, 1977). Estimated Vmax and Km values for CYP enzyme-mediated bioactivation were 680 μmol/h and 0.154 μM, respectively, and the estimated interindividual variability of Vmax is 18.8%. The intrinsic clearance of CES1 on clopidogrel hepatic metabolism (CLint,CES1_CLOP) was 932,000 L/h; the intrinsic clearance of CES1 on clop-AM hepatic metabolism (CLint,CES1_AM) was 93.1 L/h. The volume of distribution of clopidogrel in the systemic circulation (V3) was estimated as 82.2 L. The extra hepatic distribution volume of clop-AM (V5) was assumed to be primarily within plasma, which was fixed at 3 L in the present model (Frank and Gray, 1953). The basal level platelet reactivity (MPA0) for a 65 years individual was 75.8% with a 9.5% interindividual variability. The kin and kout of platelet pool were both 0.00724 1/h and the kirre of clopidogrel to platelet was 62.4 1/μM/h.

Table 2.

Model-estimated parameters for the developed PK/PD model of clopidogrel and its active metabolite.

| Parameter | Unit | Estimation | SE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QH (Harrison and Gibaldi, 1977) | (L/h) | 50 | 0 (fixed) |

| VH (Harrison and Gibaldi, 1977) | (L) | 1.5 | 0 (fixed) |

| Fa (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011) | (%) | 50 | 0 (fixed) |

| fu,p_CLOP (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011) | (%) | 2 | 0 (fixed) |

| fu,p_AM (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011) | (%) | 6 | 0 (fixed) |

| τ | (1/h) | 11.0 | 6.6 |

| V3 | (L) | 82.2 | 17.3 |

| TVVmax-CYP | (μmol/h) | 680 | 13.3 |

| Km-CYP | (μM) | 0.154 | 34 |

| TV CLint, CES1_CLOP | (L/h) | 932,000 | 6.9 |

| CLint, CES1_AM | (L/h) | 93.1 | 12.1 |

| V5 (Frank and Gray, 1953) | (L) | 3 | 0 (fixed) |

| TVMPA0 | (%) | 75.8 | 2 |

| kin | (1/h) | 0.00724 | 7.8 |

| kout | (1/h) | 0.00724 | 7.8 |

| kirre | (1/μM/h) | 62.4 | 4.5 |

| θCYP2C19-PM on TVVmax-CYP | (%) | 60.5 | 38.2 |

| θCYP2C19-IM on TVVmax-CYP | (%) | 73.8 | 13.7 |

| θCES1-TC on TVCLint,CES1 | (%) | 82.9 | 55.9 |

| θBMI on TVVmax-CYP | – | 0.668 | 28 |

| θAGE on TVMPA0 | – | 0.117 | 34.5 |

| ωTVFa | (%) | 73.5 | 8.3 |

| ωTVVmax-CYP | (%) | 18.8 | 14.4 |

| ωTVMPA0 | (%) | 9.5 | 7.7 |

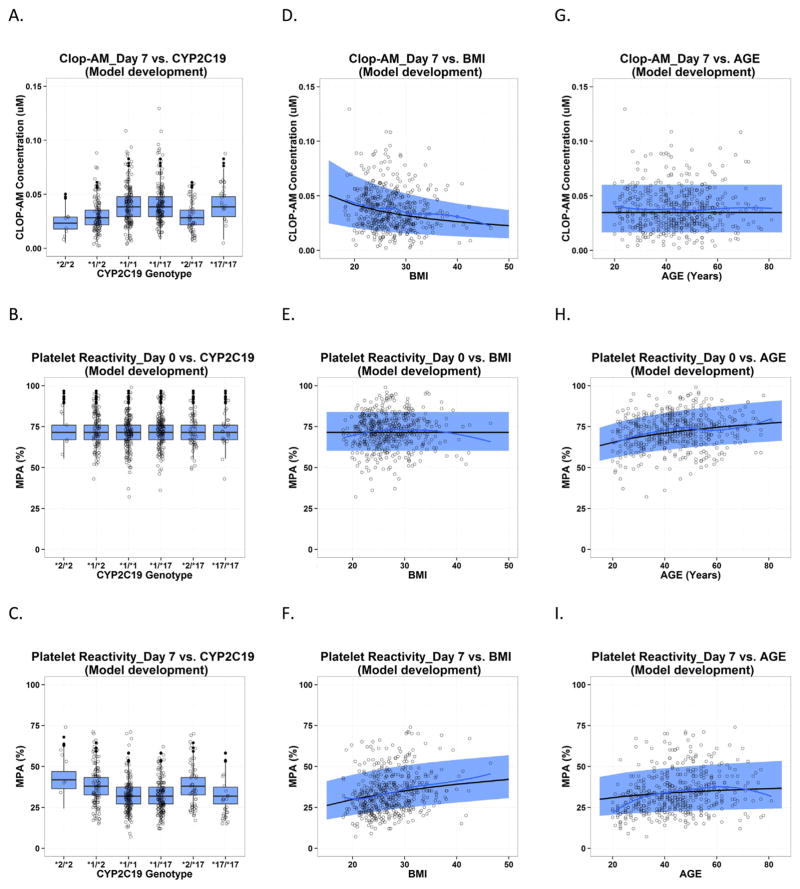

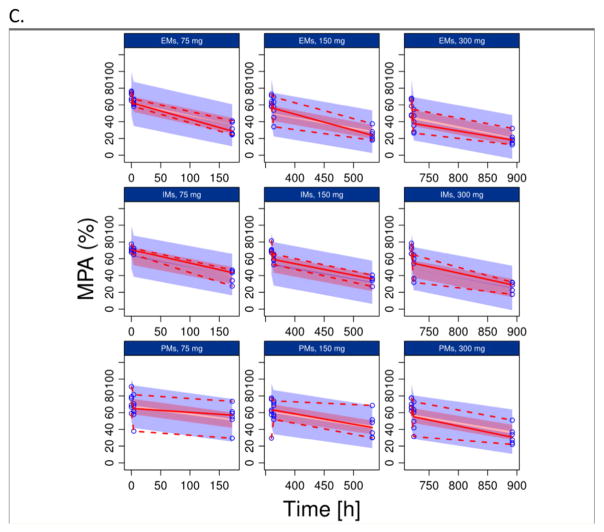

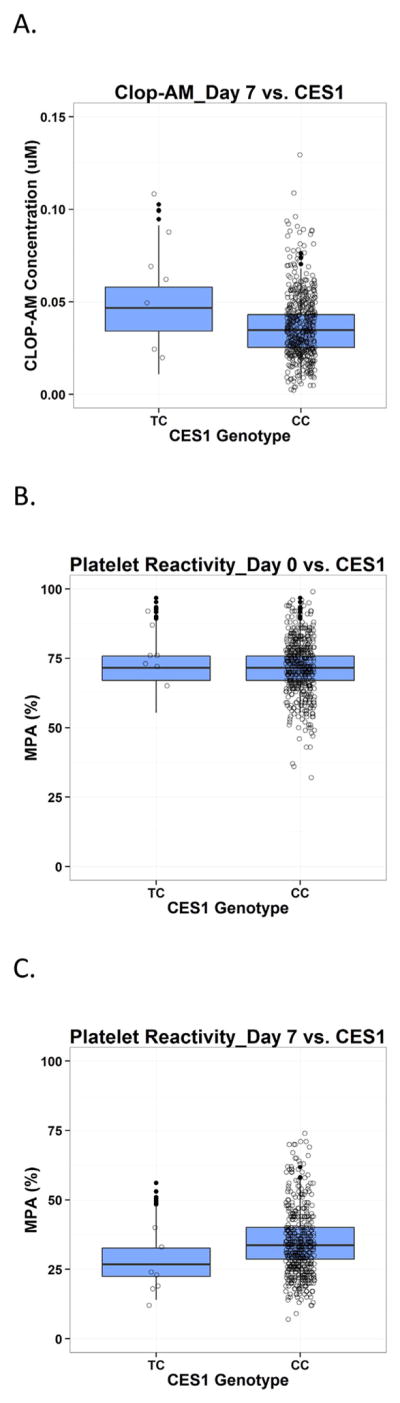

In the current analysis, age, BMI, CYP2C19*2 polymorphism and CES1 G143E polymorphism were the only statistically significant (p < 0.01) covariates characterizing interindividual differences in clopidogrel elimination/bioactivation and on-treatment platelet reactivity (Figs. 4 and 5). Compared to CYP2C19 EMs, CYP2C19 IMs and PMs show a reduced bioactivation capacity (maximal velocity, Vmax,CYPs) of 73.8% and 60.5%, respectively. Bioactivation also decreases with increase in BMI, as described by an exponent of 0.668. The CES1 G143E mutation carriers showed reduced CES1 activity (82.9%) compared to non-carriers, which results in higher clop-AM formation and decreased on-treatment platelet reactivity (Fig. 6). In addition, platelet reactivity at baseline increases as subjects become older, which affects on-treatment platelet reactivity in elderly subjects. Respective changes in baseline platelet reactivity with age were characterized by a power function with an exponent of 0.117.

Fig. 4.

Predictive check for PAPI study data used in model development, which is presented as the impact of CYP2C19 polymorphism, BMI and age on clopidogrel active metabolite (CLOP-AM) PK on Day 7 (A, D, G) and platelet reactivity (expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA)) on Day 0 at baseline (B, E and H) and on Day 7 after clopidogrel treatment (C, F and I). Each individual plot presents individual observed data (circles), loess smoothing line of the observed data (black solid line), the median (gray dashed line) and 90% confidence interval (semitransparent light gray field) for model predictions by age and BMI, and boxplot for model predictions by CYP2C19 polymorphism.

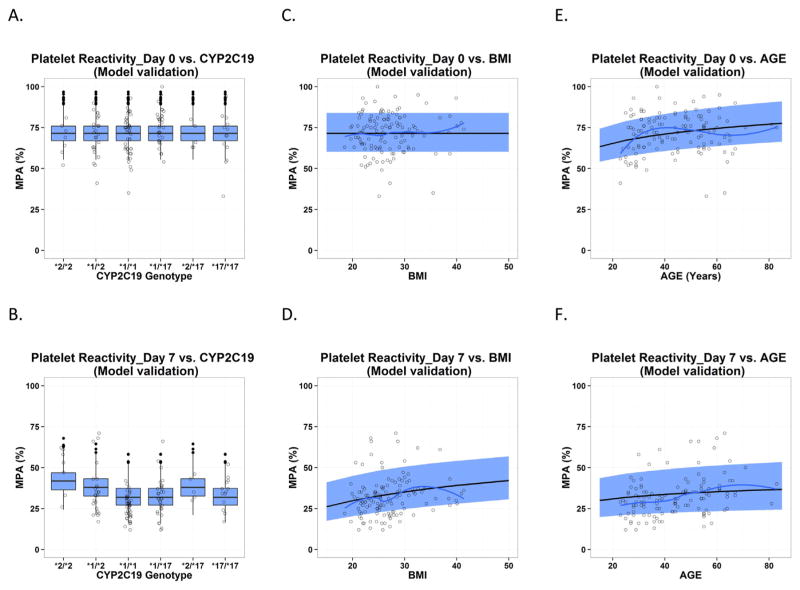

Fig. 5.

Predictive check for PAPI study data used in model qualification, which is presented as the impact of CYP2C19 polymorphism, BMI and age on platelet reactivity (expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA)) on Day 0 at baseline (A, C and E) and on Day 7 after clopidogrel treatment (B, D and F). Each individual plot presents individual observed data (circles), loess smoothing line of the observed data (black solid line), the median (gray dashed line) and 90% confidence interval (semitransparent light gray field) for model predictions by age and BMI, and boxplot for model predictions by CYP2C19 polymorphism.

Fig. 6.

Predictive check for PAPI study data on the impact of CES1 polymorphism on clopidogrel active metabolite (CLOP-AM) PK (A) as well as platelet reactivity (expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA)) on Day 0 at baseline (B) and on Day 7 after clopidogrel treatment (C). Each individual plot presents individual observed data (circles) and boxplots for model predictions. TC: CES1 G143E mutation carriers; CC: CES1 wild-type subjects.

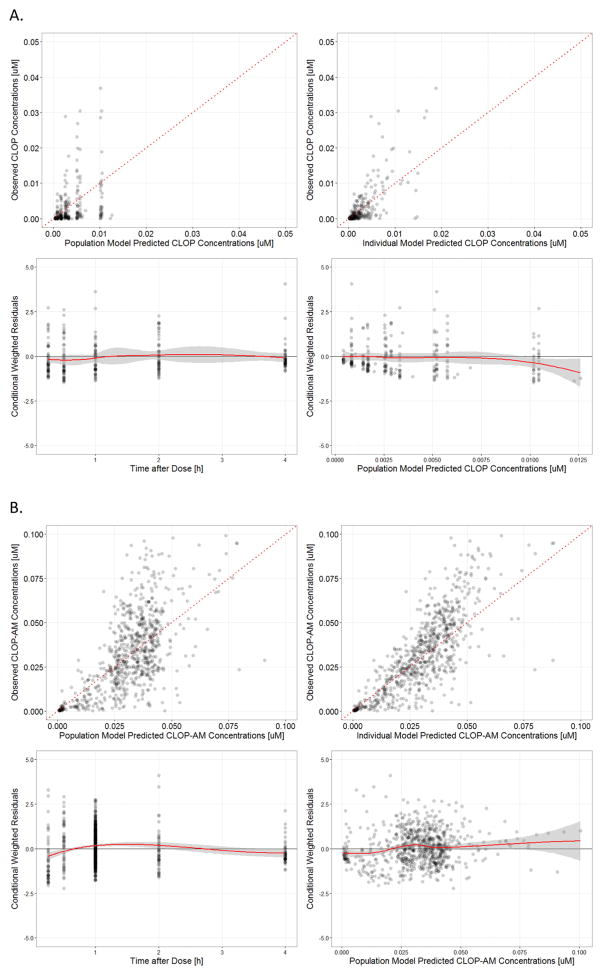

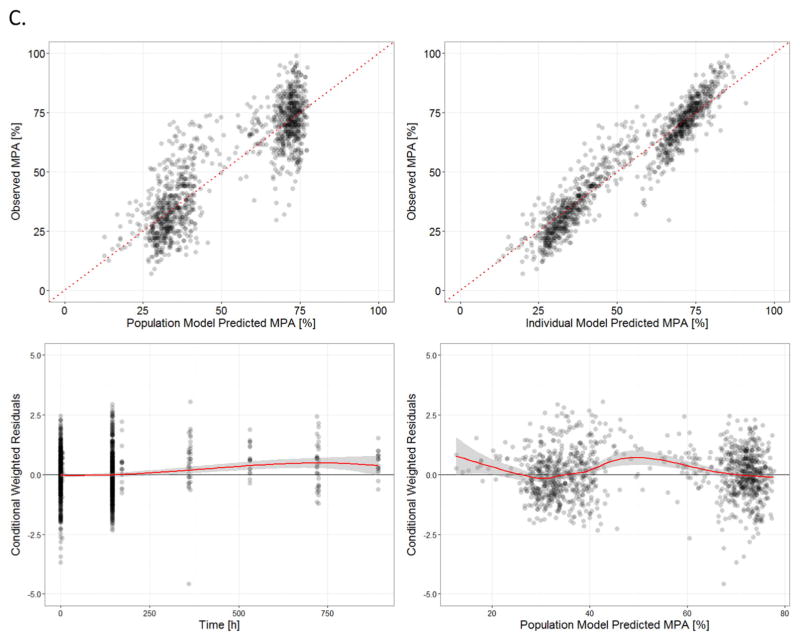

The basic goodness-of-fit plots for clopidogrel (Fig. 2A), clop-AM (Fig. 2B), and MPA (Fig. 2C) using the final model are presented in Fig. 2. In the DV versus PRED and DV versus IPRED plots, no obvious deviation was observed between predictions and observations; CWRES versus time and CWRES versus PRED plots are randomly distributed around 0. Our post-hoc analysis showed that the goodness-of-fit plots for clopidogrel, clop-AM and platelet reactivity also exhibited similar ranges and distributions (Individual plots not shown) for all three CYP2C19 phenotypes (EMs, IMs and PMs). In Fig. 2C, both the DV versus PRED and DV versus IPRED plots exhibited two discrete populations. This is due to the fact that the majority of observed PD data was obtained from the PAPI study (N = 480), which contains two observations per subject: pre-treatment baseline on Day 0 and platelet reactivity 1 h after the last dose on Day 7, whereas the PGXB2B study (N = 17) contains three observations per subject: pretreatment baseline as well as 4 h after 1st dose and last dose.

Fig. 2.

Standard goodness-of-fit plots (top left panel: observed versus population model predicted, top right panel: observed versus individual model predicted, bottom left panel: conditional weighted residuals versus time after dose and bottom right panel: conditional weighted residuals versus population predicted) for: (A) clopidogrel (CLOP), (B) its active metabolite (CLOP-AM) and (C) platelet reactivity (expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA)).

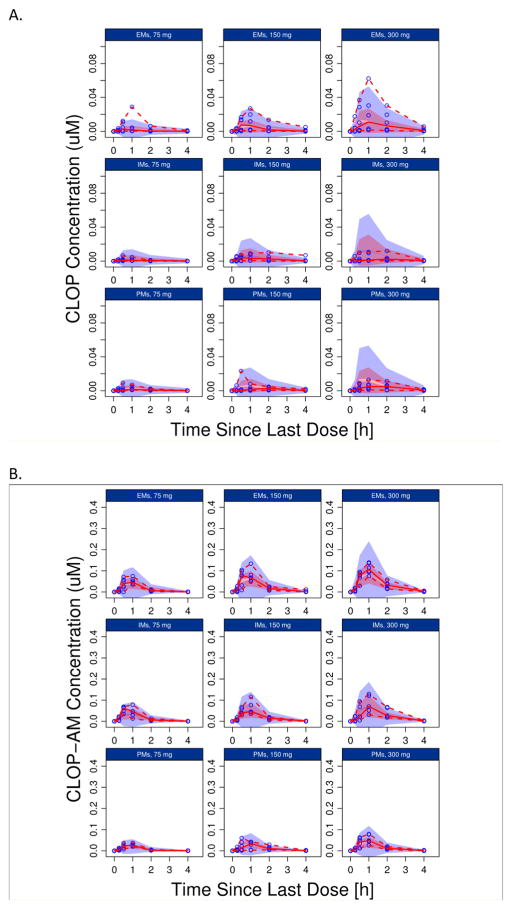

The results of PC-VPC for PGXB2B data are presented in Fig. 3 (3A: clopidogrel, 3B clop-AM, 3C: MPA), which suggested that the final model described the data across different doses levels and CYP2C19 genotypes reasonably well. In addition, the developed model appropriately characterized the impact of CYP2C19 polymorphism, BMI and age, respectively, on PAPI study clop-AM PK and PD data included in both model development (Fig. 4) and model qualification (Fig. 5). The observed data points from the PAPI study are all evenly distributed from 50% of model prediction, and more than 90% of observations are contained within 90% prediction interval, further confirming the ability of the developed model to simultaneously characterize multiple factors that contribute to interindividual variability in clopidogrel response. The developed model also reasonably characterized the impact of CES1 polymorphism on clop-AM PK and PD, as shown by the VPC result (Fig. 6).

Fig. 3.

Prediction-corrected visual predictive check (pcVPC) for: (A) clopidogrel (CLOP), (B) its active metabolite (CLOP-AM) and (C) platelet reactivity (expressed as maximal platelet aggregation (MPA)) using data from the PGXB2B study. For each observation, data was split by dose (75, 150 and 300 mg, respectively) and the CYP2C19 phenotype (EMs, IMs and PMs, respectively). Each individual plot presents individual observed data (black circles), median (solid black line), 5th and 95th percentiles (dashed black lines) for the observed data, and 95% confidence intervals for the median (semitransparent dark gray field), 5% and 95% percentiles (semitransparent light gray fields) for model predictions.

4. Discussion

Numerous studies have been performed in recent years to investigate the key factors that contribute to the high between-subject variability in clopidogrel response, and in particular to clopidogrel resistance (Angiolillo et al., 2007). However, most of these studies were either set up for investigating the impact of a single factor (e.g. age, genetic polymorphism in a single enzyme) or for determining the impact of multiple factors in a primarily qualitative fashion. There are also a number of PK/PD analyses available in the literature. However, many of these studies face a variety of limitations. For example, the work published by Lee et al. (2012) as well as Yousef et al. (2013) primarily focused on the characterization of inactive metabolite kinetics, which is unlikely to be reflective of clopidogrel’s therapeutic effect. There are also studies (Djebli et al., 2015; Yun et al., 2014) that focus on an isolated PK or PD question or use parameterizations (e.g. nonlinear absorption processes to characterize saturable bioactivation) that are not physiologically relevant (Ernest et al., 2008). In fact, the relatively large number of potential demographic or genetic covariates and combinations thereof as well as the saturation of bioactivation pathways at high dose levels (Collet et al., 2011; Horenstein et al., 2014; Wallentin et al., 2008) outlines the importance of interpreting these factors in an integrated and physiologically-based fashion, e.g. using a physiology-directed pop-PK/PD modeling and simulation approach. The objective of our study was, therefore, to integrate all available demographic and genetic information from the PAPI study (Shuldiner et al., 2009) and PGXB2B study (Horenstein et al., 2014) in a single, unifying model to characterize the intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting dose–concentration–response relationship of clopidogrel. To this end, we developed a pop-PK/PD model that integrates knowledge on the underlying physiological processes that are involved in the formation, disposition and irreversible platelet inhibition as well as demographic and pharmacogenetic factors that impact clopidogrel’s PK and PD into a single unifying model structure.

The developed model characterizes the PK/PD relationship of clopidogrel reasonably well, as reflected by mean prediction/observation ratios of systemic exposure to clop-AM and MPA, which were within 0.83–1.08 and 0.85–1.15 ranges, respectively, for all CYP2C19 phenotypes and clopidogrel dose levels, as compared to the original data reported in literature (Horenstein et al., 2014; Shuldiner et al., 2009). In the current model, Fa of clopidogrel was fixed to 50% based on the fact that about 50% of orally administered 14C-labeled clopidogrel was recovered in the urine (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011). The model estimated inter-individual variability of Fa is relatively high (73.5%), which is consistent with the observed variability in Cmax (60%) and AUC (50%), respectively (Taubert et al., 2004). It has been reported that about 85% to 90% absorbed clopidogrel is metabolized by CES1 to and only about 2% of absorbed drug converted to clop-AM and entered to systemic circulation (Bonello et al., 2010; Sanofi-Aventis, 2011). Our model estimated intrinsic clearance of CES1 on clopidogrel hepatic metabolism is 932,000 L/h, whereas the derived intrinsic clearance of CYPs on clopidogrel hepatic activation is 4416 L/h. After incorporating these values in conjunction with protein binding information for clopidogrel and clop-AM (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011) into the well-stirred model (Wilkinson and Shand, 1975) for hepatic clearance, it was suggested that clopidogrel has a very high hepatic extraction ratio. 93% and 4.5% of the absorbed drug were metabolized by CES1 and CYP enzymes, respectively, indicating that the estimated model parameter values from our current model analysis show a trend that is similar to what observed in patients. This result also indicates that clopidogrel bioactivation majorly occurs during its hepatic first pass metabolism before the parent compound enters the systemic circulation. Model predicted that only 2.5% of the absorbed clopidogrel entered the systemic circulation, considering the high hepatic extraction of clopidogrel (93%), it can be expected that active metabolite generated by systemic circulated clopidogrel should be minimal. On the other hand, clop-AM has a low hepatic extraction ratio, given that about 10% of the formed clop-AM is further metabolized by hepatic CES1, while the remaining 90% entered the systemic circulation. The results from a non-compartmental analysis of the PGXB2B study data showed that increasing the clopidogrel dose from 75 mg to 300 mg caused a 2-fold increase in systemic clop-AM exposure, suggesting that clopidogrel bioactivation is saturable (Horenstein et al., 2014). Our model simulated hepatic clopidogrel free concentration profiles revealed that hepatic clopidogrel free concentrations elevated to above km (0.154 μM) value when clopidogrel dose increased from 75 to 150 and 300 mg (Fig. S2), confirming the saturation process of clopidogrel bioactivation with the increase of dose.

As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, the current model analysis qualitatively and quantitatively described the impact of several genetic and non-genetic covariates, including CYP2C19*2 mutation, BMI and age, and confirmed previous literature findings (Cuisset et al., 2011; FDA, 2010; Frelinger et al., 2013; Hochholzer et al., 2010; Hulot et al., 2006; Mega et al., 2009; Shuldiner et al., 2009; Siller-Matula et al., 2012; Simon et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2013). Multivariate analysis of the PAPI study already suggested that CYP2C19, age and BMI explain 12%, 3.8% and 2.3% of the interindividual variability in on treatment platelet reactivity (Shuldiner et al., 2009). Our model analysis confirms these results and shows that inclusion of CYP2C19 and BMI explained 16% and 14% of the interindividual variability in Vmax,CYPs, respectively. In addition, age accounted for 6.3% of the interindividual variability in MPA0. Our findings also confirm that the between-subject variability in response to clopidogrel treatment is the result of a combination of both demographic and genetic factors, as shown in Fig. S1. For example, on-treatment platelet reactivity (expressed as MPA) in CYP2C19 EMs was affected by both age and BMI given that, in subjects younger than 55 years, MPA was 26% in lean ones (BMI < 25 kg/m2), 30% in overweight ones (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) and 35% in obese ones (BMI > 30 kg/m2), which was 30%, 35% and 39%, respectively, in their BMI-matched elderly peers (age > 70 years) following administration of the same standard dosing regimen. This result is consistent with findings from a recent clinical study, which reported that the proportion of nondiabetic patients with HPR increases with age and BMI (Hochholzer et al., 2010). In recent years, researchers have started to investigate the possibility of “escalating” clopidogrel doses in order to overcome HPR, particularly in patients with CYP2C19 loss of function polymorphisms, by increasing systemic clop-AM exposure. However, the results were highly variable (Howell et al., 2015). Our model prediction results showed that an increase of the clopidogrel maintenance dose from 75 mg to 300 mg may be sufficient for CYP2C19 poor metabolizers with normal body weight (BMI = 25 kg/m2) to achieve a systemic clop-AM exposure similar to that in EMs following a 75 mg clopidogrel maintenance dose. This finding is consistent with observations from the PGXB2B study, where subjects have an average BMI of 27.7 ± 4.7 kg/m2. On the other hand, our model prediction also suggests that in obese subjects (BMI > 40 kg/m2) who are also CYP2C19 PMs, a further increase of the clopidogrel maintenance dose to 600 mg may be necessary in order to achieve the desired systemic clop-AM exposure and, thus, optimal anti-platelet effect in these subjects. This is likely due to the fact that severe obesity (BMI > 40 kg/m2) is associated with a significant decrease in clopidogrel bioactivation, as confirmed by a recent reported clinical PK/PD study (Wagner et al., 2014).

Several recent studies report an impact of CES1 polymorphisms on clopidogrel response in patients (Lewis et al., 2013b; Tarkiainen et al., 2015; Xie et al., 2014; Zou et al., 2014). This is consistent with findings of the PAPI study, which show that clop-AM plasma concentrations are significantly higher in CES1 G143E-allele carriers vs. wild-type subjects (30.3 ± 6.1 vs. 19.0 ± 0.4 ng/ml, P = 0.001). Consistently, the CES1 G143E-allele carriers also exhibited a better clopidogrel response (P = 0.003). This is due to the fact that a decrease in CES1 activity leads to a decrease in clopidogrel and clop-AM hydrolysis and a subsequent increase in the fraction of drug that becomes available for bioactivation and systemic circulation and, thus, for exerting its pharmacological effect, as confirmed by a recent in vitro study (Zhu et al., 2013). Our analysis with PAPI study PK/PD data suggests that polymorphisms in CES1 may play an important role for clopidogrel’s PK and PD, as CES1 G143E mutation caused ~17% decrease in CES1 activity, which caused significant elevation in clop-AM systemic concentrations (Fig. 6A) and, thus, lower on-treatment platelet reactivity (Fig. 6C), but didn’t affect baseline platelet reactivity (Fig. 6B). However, these results are mainly exploratory as the findings are limited by the small number of subjects (n = 7) that are CES1 G143E mutation carriers. More data will be necessary in order to conclusively evaluate the impact of different CES1 mutations on clopidogrel’s PK and PD.

The physiology-directed pop-PK/PD model developed in this study is uniquely different from conventional pop-PK/PD models due to its mechanistic feature. It was developed by adopting a semiphysiological PK model developed by Gordi et al. (2005). The liver compartment was separated from the rest of the central compartment due to the fact that it harbors both CYP and CES1 enzymes that mediate the bioactivation and enzymatic breakdown of clopidogrel and its active metabolites (Kazui et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2013). The two-step bioactivation of clopidogrel that takes place in the liver was characterized in a single step due to the absence of intermediate metabolite data (Kazui et al., 2010). The impact of protein binding on drug distribution between blood and liver as well as its impact on hepatic drug metabolism was also considered. Since plasma proteins, such as albumin, are synthesized and secreted to the blood by hepatoctyes (Crane and Miller, 1977), we assumed that the protein binding in the hepatocytes is similar to that in the blood in our analysis. As a consequence, we employed the experimentally determined in vitro plasma protein binding values of clopidogrel (98%) and clop-AM (94%) in order to account for protein binding in both blood and liver. However, we appreciate the fact that the scaling of in vitro data to in vivo situations faces some limitations (Schmidt et al., 2008). For example, a substantial difference between the model estimated in vivo Km value (0.154 μM) and the reported in vitro Km values of the 2-step clopidogrel bioactivation process (1.12–2.08 μM and 1.62–27.8 μM of step 1 and step 2, respectively) by a variety of recombinant CYP enzymes (CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP3A4, CYP2B6 and CYP1A2) (Kazui et al., 2010) was found in our analysis. Such difference may be attributed to the fact that, in the current model, the impact of the high protein binding of clopidogrel (98%) and clop-AM (94%) are taken into consideration (Sanofi-Aventis, 2011), whereas the in vitro Km values (1.12–27.8 μM) were based on total drug concentrations without considering the potential impact of unspecific binding of clopidogrel and its metabolites to microsomal proteins (Kazui et al., 2010; McLure et al., 2000). In fact, it has been shown that microsomal protein binding significantly contributes to the observed discrepancies between predicted hepatic clearance based on in vitro data and corresponding in vivo values (McLure et al., 2000). Several methods have already been proposed to predict the impact of microsomal binding (Hallifax and Houston, 2006; Turner et al., 2006). Using the method proposed by Hallifax and Houston (2006), the predicted unbound fraction of clopidogrel and 2-oxo-clopidogrel in the microsomal system was 0.23 and 0.91, respectively. So the calculated unbound Km values were 0.26–0.48 μM for step 1 bioactivation and 1.47–25.3 μM for step 2 bioactivation. Using another method proposed by Turner et al. (2006), the predicted unbound fraction of clopidogrel and 2-oxo-clopidogrel in the microsomal system was 0.74 (0.83–1.54 μM) and 0.97 (1.57–27.0 μM), respectively. However, a recent published clopidogrel PBPK model developed with Simcyp (Djebli et al., 2015) reported that the estimated unbound fraction values 0.015 and 0.18, which turned out to best characterize unbound fraction of clopidogrel and 2-oxo-clopidogrel in the microsomal system, respectively, were significantly lower than the unbound fraction values obtained from prediction methods derived from historical data (Hallifax and Houston, 2006; Turner et al., 2006); and the resultant unbound Km values were 0.017–0.039 μM and 0.29–5.00 μM for step 1 and step 2 of the 2-step clopidogrel bioactivation process, respectively. Interestingly, this set of unbound Km values (0.017–5.00 μM) was within the same range of our model estimated free in vivo Km value (0.154 μM), which is a lumped value that characterizes the overall 2-step bioactivation process, indicating that our model may provide a reasonable characterization of free in vivo Km value. Additional analysis was also performed to assess the sensitivity of the estimated in vivo Km value on clopidogrel PK/PD by either increase or decrease the Km value 10-folds while maintaining the same intrinsic clearance of the formation of clop-AM from clopidogrel (CLint, CYPs_CLOP). Our results showed that, compared to the reference group (Km = 0.154 μM), systemic exposure to clopidogrel was almost identical after 10-fold changes in Km (0.0154 μM or 1.54 μM), which is due to the fact that the majority of absorbed clopidogrel (93%) was metabolized by CES1 and variation in CYP enzymes mediated bioactivation pathway didn’t significantly impact the PK of clopidogrel itself. On the other hand, the sensitivity analysis results revealed that changes in Km dramatically affected systemic exposure to clop-AM as well as on treatment platelet reactivity. For example, at the dose level of 75 mg, decrease of Km value 10-fold caused a 68% decrease of clop-AM AUC value and a resultant 24% increase of on-treatment platelet reactivity; whereas a 10-fold increase of Km value led to a 36% increase of clop-AM AUC value and 10% decrease of on-treatment platelet reactivity. More pronounced change was observed at the dose level of 300 mg: Ten-fold decrease or increase of Km value caused 80% decrease or 114% increase of clop-AM AUC values as well as 68% increase or 41% decrease of on-treatment platelet reactivity values, respectively. Such divergence could be explained by a more profound impact of saturation in hepatic CYP enzyme at higher doses compared lower doses, as also revealed by our model simulated hepatic clopidogrel free concentration profile (Fig. S2). Ultimately, these sensitivity analysis results suggested that our proposed physiology-directed PK/PD model provided a reasonable characterization of some of the key physiological process in terms of clopidogrel bioactivation. At PD part, the first-order elimination rate constant for natural platelet turnover kout was estimated as 0.00724 1/h, which translates into an average platelet half-life of about 4 days. This value is close to the observed platelet life span in adults (5 to 10 days) (Najean et al., 1969). In comparison, the rate constant associated with the clop-AM-mediated inactivation of platelets (kirre) was estimated as 62.4 1/μM/h, which underscores the efficiency of the inactivation process.

During model development, the PGXB2B study data that has rich information on clopidogrel and clop-AM plasma concentrations and maximal platelet aggregation measurements was first used to build the structural model. The estimated Km values for CYP enzyme-mediated bioactivation was 0.154 μM and the estimated extra-hepatic distribution volume of clop-AM (V5) was close to plasma volume (3 L) (Frank and Gray, 1953). In the later full model development step, the Km and V5 values were fixed to 0.154 μM and 3 L, respectively, to stabilize the model estimation as newly added PAPI study data only contains clopidogrel PK and PD information at one and two time points, respectively. During covariate model development, the impact of CYP2C19 gain-of-function mutations (*1/*17 or *17/*17), PON1 and sex were also tested but were found to be uninfluential (e.g. a less than 5% increase in clopidogrel bioactivation for CYP2C19 gain-of-function mutation (*1/*17 or *17/*17) carriers. This result is in line with results from several clinical studies, where no clear correlation between CYP2C19*17 polymorphism and increased platelet inhibition, reduction of major cardiovascular risk or increase in bleeding events was identified (Delaney et al., 2012; Gurbel et al., 2011; Lewis et al., 2013a; Pare et al., 2010; Sibbing et al., 2010; Siller-Matula et al., 2012; Zabalza et al., 2012). Respective results for sex and PON1 polymorphisms are in line with findings from other PK/PD studies (Gong et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2013a; Shuldiner et al., 2009), where they were also found uninfluential.

The need for a physiology-directed exploration and interpretation of sources of between-subject variability for clopidogrel is further supported by findings from the PAPI study, which show that only about 12% of the between-subject variability in treatment response is associated with polymorphisms in CYP2C19. This renders the need for use of innovative quantitative analysis techniques that allow the identification of additional intrinsic and extrinsic factors as well as their dynamic interplay (Jiang et al., 2015). Our model is a first step in that direction as it integrates knowledge on the underlying (patho)physiology, the drug’s metabolism and mechanism of action as well as covariate relationships into a single, unifying approach. However, given the complexity of clopidogrel’s metabolism, this first generation model may have to be further expanded by, e.g. accounting for the relative contribution of additional CYP enzymes as well as their genetic variance to the two-step bioactivation (Kazui et al., 2010), in order to be able to better characterize and predict inter-individual differences in response to clopidogrel treatment (see Fig. 2C). In addition, other comorbidities, such as the impact of type 2 diabetes on clopidogrel’s treatment response should be incorporated as it has been shown to affect the response to clopidogrel treatment at least partially by suppressing CYP2C19 activity (Erlinge et al., 2008). Ultimately, this next generation population PK/PD model holds the potential to be further developed to serve as a bed-side ready decision support tool to guide optimal dosing on a patient-by-patient basis or to identify potential sources of variability. As such this model can not only be used for posterior hypothesis testing by also for prospective hypothesis generation and, thus, to guide clinical trial design.

In conclusion, we developed a population PK/PD model that integrates knowledge on the disposition and bioactivation of clopidogrel as well as the subsequent platelet inhibition by its active metabolite. The developed model allowed to simultaneously characterize the impact of CYP2C19 and to some extent of CES1 polymorphism as well as age and BMI on clopidogrel’s dose–concentration–response relationship. The proposed model represents a critical first step forward in our understanding of clinically relevant risk factors for clopidogrel treatment. It also highlights the importance of a physiology-directed understanding of the underlying biological processes for reducing unexplained variability and ultimately for guiding optimal dose selection prior to the start of therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the work of Drs. Rajnikanth Madabushi, Issam Zineh, Michael Pacanowski and Joo Yeon Lee from the Office of Clinical Pharmacology, Food and Drug Administration who worked on the PGXB2B Study and analyzed that study’s data. Drs. Cody J. Peer and William D. Figg from the Clinical Pharmacology Program, Office of the Clinical Director, National Cancer Institute who developed a new method and measured clopidogrel and clopidogrel active metabolite levels are also gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCATS Clinical and Translational Science Award to the University of Florida UL1 TR000064 as well as NIH Grants GM074518-05 and GM074518-05S1.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejps.2015.10.024.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Alfonso F, Macaya C, Bass TA, Costa MA. Variability in individual responsiveness to clopidogrel: clinical implications, management, and future perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1505–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogman K, Silkey M, Chan SP, Tomlinson B, Weber C. Influence of CYP2C19 genotype on the pharmacokinetics of R483, a CYP2C19 substrate, in healthy subjects and type 2 diabetes patients. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:1005–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00228-010-0840-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonello L, Tantry US, Marcucci R, Blindt R, Angiolillo DJ, Becker R, Bhatt DL, Cattaneo M, Collet JP, Cuisset T, Gachet C, Montalescot G, Jennings LK, Kereiakes D, Sibbing D, Trenk D, Van Werkum JW, Paganelli F, Price MJ, Waksman R, Gurbel PA. Consensus and future directions on the definition of high on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:919–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman HJ, Schomig E, van Werkum JW, Velder J, Hackeng CM, Hirschhauser C, Waldmann C, Schmalz HG, ten Berg JM, Taubert D. Paraoxonase-1 is a major determinant of clopidogrel efficacy. Nat Med. 2011;17:110–116. doi: 10.1038/nm.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet JP, Hulot JS, Anzaha G, Pena A, Chastre T, Caron C, Silvain J, Cayla G, Bellemain-Appaix A, Vignalou JB, Galier S, Barthelemy O, Beygui F, Gallois V, Montalescot G. High doses of clopidogrel to overcome genetic resistance: the randomized crossover CLOVIS-2 (Clopidogrel and Response Variability Investigation Study 2) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane LJ, Miller DL. Plasma protein synthesis by isolated rat hepatocytes. J Cell Biol. 1977;72:11–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.72.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuisset T, Quilici J, Grosdidier C, Fourcade L, Gaborit B, Pankert M, Molines L, Morange PE, Bonnet JL, Alessi MC. Comparison of platelet reactivity and clopidogrel response in patients </=75 years versus >75 years undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1411–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayneka NL, Garg V, Jusko WJ. Comparison of four basic models of indirect pharmacodynamic responses. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1993;21:457–478. doi: 10.1007/BF01061691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Morais SM, Wilkinson GR, Blaisdell J, Meyer UA, Nakamura K, Goldstein JA. Identification of a new genetic defect responsible for the polymorphism of (S)-mephenytoin metabolism in Japanese. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;46:594–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney JT, Ramirez AH, Bowton E, Pulley JM, Basford MA, Schildcrout JS, Shi Y, Zink R, Oetjens M, Xu H, Cleator JH, Jahangir E, Ritchie MD, Masys DR, Roden DM, Crawford DC, Denny JC. Predicting clopidogrel response using DNA samples linked to an electronic health record. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91:257–263. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desta Z, Zhao X, Shin JG, Flockhart DA. Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:913–958. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241120-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djebli N, Fabre D, Boulenc X, Fabre G, Sultan E, Hurbin F. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling for sequential metabolism: effect of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism on clopidogrel and clopidogrel active metabolite pharmacokinetics. Drug Metab Dispos. 2015;43:510–522. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.062596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlinge D, Varenhorst C, Braun OO, James S, Winters KJ, Jakubowski JA, Brandt JT, Sugidachi A, Siegbahn A, Wallentin L. Patients with poor responsiveness to thienopyridine treatment or with diabetes have lower levels of circulating active metabolite, but their platelets respond normally to active metabolite added ex vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1968–1977. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernest CS, II, Small DS, Rohatagi S, Salazar DE, Wallentin L, Winters KJ, Wrishko RE. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of prasugrel and clopidogrel in aspirin-treated patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2008;35:593–618. doi: 10.1007/s10928-008-9103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Reduced effectiveness of Plavix (Clopidogrel) in Patients Who are Poor Metabolizers of the Drug 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Frank H, Gray SJ. The determination of plasma volume in man with radioactive chromic chloride. J Clin Invest. 1953;32:991–999. doi: 10.1172/JCI102825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frelinger AL, III, Bhatt DL, Lee RD, Mulford DJ, Wu J, Nudurupati S, Nigam A, Lampa M, Brooks JK, Barnard MR, Michelson AD. Clopidogrel pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics vary widely despite exclusion or control of polymorphisms (CYP2C19, ABCB1, PON1), noncompliance, diet, smoking, co-medications (including proton pump inhibitors), and pre-existent variability in platelet function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler T, Schaeffeler E, Dippon J, Winter S, Buse V, Bischofs C, Zuern C, Moerike K, Gawaz M, Schwab M. CYP2C19 and nongenetic factors predict poor responsiveness to clopidogrel loading dose after coronary stent implantation. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:1251–1259. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.9.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong IY, Crown N, Suen CM, Schwarz UI, Dresser GK, Knauer MJ, Sugiyama D, Degorter MK, Woolsey S, Tirona RG, Kim RB. Clarifying the importance of CYP2C19 and PON1 in the mechanism of clopidogrel bioactivation and in vivo antiplatelet Response. Eur Heart J. 2012 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordi T, Xie R, Huong NV, Huong DX, Karlsson MO, Ashton M. A semiphysiological pharmacokinetic model for artemisinin in healthy subjects incorporating autoinduction of metabolism and saturable first-pass hepatic extraction. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;59:189–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbel PA, Tantry US. Clopidogrel resistance? Thromb Res. 2007;120:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hiatt BL, O’Connor CM. Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation. 2003;107:2908–2913. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072771.11429.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurbel PA, Shuldiner AR, Bliden KP, Ryan K, Pakyz RE, Tantry US. The relation between CYP2C19 genotype and phenotype in stented patients on maintenance dual antiplatelet therapy. Am Heart J. 2011;161:598–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallifax D, Houston JB. Binding of drugs to hepatic microsomes: comment and assessment of current prediction methodology with recommendation for improvement. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:724–726. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.007658. (author reply 727) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LI, Gibaldi M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for digoxin disposition in dogs and its preliminary application to humans. J Pharm Sci. 1977;66:1679–1683. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600661206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan MS, Basri HB, Hin LP, Stanslas J. Genetic polymorphisms and drug interactions leading to clopidogrel resistance: why the Asian population requires special attention. Int J Neurosci. 2013;123:143–154. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.744308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochholzer W, Trenk D, Fromm MF, Valina CM, Stratz C, Bestehorn HP, Buttner HJ, Neumann FJ. Impact of cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism and of major demographic characteristics on residual platelet function after loading and maintenance treatment with clopidogrel in patients undergoing elective coronary stent placement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2427–2434. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horenstein RB, Madabushi R, Zineh I, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Peer CJ, Schuck RN, Figg WD, Shuldiner AR, Pacanowski MA. Effectiveness of clopidogrel dose escalation to normalize active metabolite exposure and antiplatelet effects in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54:865–873. doi: 10.1002/jcph.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell LA, Stouffer GA, Polasek M, Rossi JS. Review of clopidogrel dose escalation in the current era of potent P2Y12 inhibitors. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8:411–421. doi: 10.1586/17512433.2015.1057571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulot JS, Bura A, Villard E, Azizi M, Remones V, Goyenvalle C, Aiach M, Lechat P, Gaussem P. Cytochrome P450 2C19 loss-of-function polymorphism is a major determinant of clopidogrel responsiveness in healthy subjects. Blood. 2006;108:2244–2247. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-013052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XL, Samant S, Lesko LJ, Schmidt S. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of clopidogrel. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54:147–166. doi: 10.1007/s40262-014-0230-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazui M, Nishiya Y, Ishizuka T, Hagihara K, Farid NA, Okazaki O, Ikeda T, Kurihara A. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the two oxidative steps in the bioactivation of clopidogrel to its pharmacologically active metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:92–99. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.029132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Hwang Y, Kang W, Seong SJ, Lim MS, Lee HW, Yim DS, Sohn DR, Han S, Yoon YR. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of clopidogrel in Korean healthy volunteers and stroke patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;52:985–995. doi: 10.1177/0091270011409228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP, Fisch AS, Ryan K, O’Connell JR, Gibson Q, Mitchell BD, Shen H, Tanner K, Horenstein RB, Pakzy R, Tantry US, Bliden KP, Gurbel PA, Shuldiner AR. Paraoxonase 1 (PON1) gene variants are not associated with clopidogrel response. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:568–574. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Stephens S, Horenstein R, O’Connell J, Ryan K, Peer C, Figg W, Spencer S, Pacanowski M, Mitchell B, Shuldiner A. The CYP2C19*17 variant is not Independently Associated with Clopidogrel Response. J Thromb Haemost. 2013a doi: 10.1111/jth.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JP, Horenstein RB, Ryan K, O’Connell JR, Gibson Q, Mitchell BD, Tanner K, Chai S, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Spencer SD, Pacanowski MA, Gurbel PA, Shuldiner AR. The functional G143E variant of carboxylesterase 1 is associated with increased clopidogrel active metabolite levels and greater clopidogrel response. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2013b;23:1–8. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835aa8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandema JW, Verotta D, Sheiner LB. Building population pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic models. I Models for covariate effects. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1992;20:511–528. doi: 10.1007/BF01061469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matetzky S, Shenkman B, Guetta V, Shechter M, Beinart R, Goldenberg I, Novikov I, Pres H, Savion N, Varon D, Hod H. Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:3171–3175. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130846.46168.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLure JA, Miners JO, Birkett DJ. Nonspecific binding of drugs to human liver microsomes. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49:453–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, Sabatine MS. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najean Y, Ardaillou N, Dresch C. Platelet lifespan. Annu Rev Med. 1969;20:47–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.20.020169.000403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare G, Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Anand SS, Connolly SJ, Hirsh J, Simonsen K, Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Eikelboom JW. Effects of CYP2C19 genotype on outcomes of clopidogrel treatment. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1704–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrono C. The P2Y12 receptor: no active metabolite, no party. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:271–272. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peer CJ, Spencer SD, VanDenBerg DA, Pacanowski MA, Horenstein RB, Figg WD. A sensitive and rapid ultra HPLC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous detection of clopidogrel and its derivatized active thiol metabolite in human plasma. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;880:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry CG, Shuldiner AR. Pharmacogenomics of anti-platelet therapy: how much evidence is enough for clinical implementation? J Hum Genet. 2013;58:339–345. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2013.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanofi-Aventis. PRODUCT MONOGRAPH: Plavix Clopidogrel 75 and 300 mg Tablets, Manufacturer’s Standard 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt S, Rock K, Sahre M, Burkhardt O, Brunner M, Lobmeyer MT, Derendorf H. Effect of protein binding on the pharmacological activity of highly bound antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3994–4000. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00427-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuldiner AR, O’Connell JR, Bliden KP, Gandhi A, Ryan K, Horenstein RB, Damcott CM, Pakyz R, Tantry US, Gibson Q, Pollin TI, Post W, Parsa A, Mitchell BD, Faraday N, Herzog W, Gurbel PA. Association of cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype with the antiplatelet effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel therapy. JAMA. 2009;302:849–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibbing D, Koch W, Gebhard D, Schuster T, Braun S, Stegherr J, Morath T, Schomig A, von Beckerath N, Kastrati A. Cytochrome 2C19*17 allelic variant, platelet aggregation, bleeding events, and stent thrombosis in clopidogrel-treated patients with coronary stent placement. Circulation. 2010;121:512–518. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.885194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller-Matula JM, Delle-Karth G, Lang IM, Neunteufl T, Kozinski M, Kubica J, Maurer G, Linkowska K, Grzybowski T, Huber K, Jilma B. Phenotyping vs. genotyping for prediction of clopidogrel efficacy and safety: the PEGASUS-PCI study. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:529–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon T, Verstuyft C, Mary-Krause M, Quteineh L, Drouet E, Meneveau N, Steg PG, Ferrieres J, Danchin N, Becquemont L French Registry of Acute STE, Non STEMII. Genetic determinants of response to clopidogrel and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:363–375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarkiainen EK, Holmberg MT, Tornio A, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ, Backman JT, Niemi M. Carboxylesterase 1 c. 428G > a single nucleotide variation increases the antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel by reducing its hydrolysis in humans. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97:650–658. doi: 10.1002/cpt.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert D, Kastrati A, Harlfinger S, Gorchakova O, Lazar A, von Beckerath N, Schomig A, Schomig E. Pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel after administration of a high loading dose. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:311–316. doi: 10.1160/TH04-02-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert D, von Beckerath N, Grimberg G, Lazar A, Jung N, Goeser T, Kastrati A, Schomig A, Schomig E. Impact of P-glycoprotein on clopidogrel absorption. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:486–501. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner DB, Rostami-Hodjegan A, Tucker GT, Rowland-Yeo K. Prediction of non-Specific Hepatic Microsomal Binding from Readily Available Physicochemical Properties. 9th European ISSX Meeting; June 4th–7th (2006); Manchester, UK. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Angiolillo DJ, Ten Berg JM, Bergmeijer TO, Jakubowski JA, Small DS, Moser BA, Zhou C, Brown P, James S, Winters KJ, Erlinge D. Higher body weight patients on clopidogrel maintenance therapy have lower active metabolite concentrations, lower levels of platelet inhibition, and higher rates of poor responders than low body weight patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11239-013-0987-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner H, Angiolillo DJ, Ten Berg JM, Bergmeijer TO, Jakubowski JA, Small DS, Moser BA, Zhou C, Brown P, James S, Winters KJ, Erlinge D. Higher body weight patients on clopidogrel maintenance therapy have lower active metabolite concentrations, lower levels of platelet inhibition, and higher rates of poor responders than low body weight patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2014;38:127–136. doi: 10.1007/s11239-013-0987-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallentin L, Varenhorst C, James S, Erlinge D, Braun OO, Jakubowski JA, Sugidachi A, Winters KJ, Siegbahn A. Prasugrel achieves greater and faster P2Y12receptor-mediated platelet inhibition than clopidogrel due to more efficient generation of its active metabolite in aspirin-treated patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:21–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson GR, Shand DG. Commentary: a physiological approach to hepatic drug clearance. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1975;18:377–390. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975184377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RS, Anderson JL, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE, Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Jneid H, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Philippides GJ, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP, Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, II, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart association task force on practice guidelines developed in collaboration with the American academy of family physicians, society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions, and the society of thoracic surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:e215–e367. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C, Ding X, Gao J, Wang H, Hang Y, Zhang H, Zhang J, Jiang B, Miao L. The effects of CES1A2 a(−816)C and CYP2C19 loss-of-function polymorphisms on clopidogrel response variability among Chinese patients with coronary heart disease. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2014;24:204–210. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousef AM, Melhem M, Xue B, Arafat T, Reynolds DK, Van Wart SA. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of clopidogrel in healthy jordanian subjects with emphasis optimal sampling strategy. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 2013;34:215–226. doi: 10.1002/bdd.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun HY, Kang W, Lee BY, Park S, Yoon YR, Yeul Ma J, Kwon KI. Semi-mechanistic modelling and simulation of inhibition of platelet aggregation by anti-platelet agents. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;115:352–359. doi: 10.1111/bcpt.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Chrolavicius S, Tognoni G, Fox KK. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabalza M, Subirana I, Sala J, Lluis-Ganella C, Lucas G, Tomas M, Masia R, Marrugat J, Brugada R, Elosua R. Meta-analyses of the association between cytochrome CYP2C19 loss- and gain-of-function polymorphisms and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease treated with clopidogrel. Heart. 2012;98:100–108. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2011.227652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu HJ, Wang X, Gawronski BE, Brinda BJ, Angiolillo DJ, Markowitz JS. Carboxylesterase 1 as a determinant of clopidogrel metabolism and activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:665–672. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou JJ, Chen SL, Fan HW, Tan J, He BS, Xie HG. CES1A −816C as a genetic marker to predict greater platelet clopidogrel response in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2014;63:178–183. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.