Abstract

A surge in hospital consolidation is fueling formation of ever larger multi-hospital systems throughout the United States. This article examines hospital prices in California over time with a focus on hospitals in the largest multi-hospital systems. Our data show that hospital prices in California grew substantially (+76% per hospital admission) across all hospitals and all services between 2004 and 2013 and that prices at hospitals that are members of the largest, multi-hospital systems grew substantially more (113%) than prices paid to all other California hospitals (70%). Prices were similar in both groups at the start of the period (approximately $9200 per admission). By the end of the period, prices at hospitals in the largest systems exceeded prices at other California hospitals by almost $4000 per patient admission. Our study findings are potentially useful to policy makers across the country for several reasons. Our data measure actual prices for a large sample of hospitals over a long period of time in California. California experienced its wave of consolidation much earlier than the rest of the country and as such our findings may provide some insights into what may happen across the United States from hospital consolidation including growth of large, multi-hospital systems now forming in the rest of the rest of the country.

Keywords: hospitals, hospital prices, multi-hospital systems, consolidation, hospital spending, hospital market structure

A surge in hospital consolidation is fueling the formation of ever larger multi-hospital systems throughout the United States.1 The New York Times reported, “Hospitals across the nation are being swept up in the biggest wave of mergers since the 1990s, a development that is creating giant hospital systems that could one day dominate American health care and drive up costs.”2 The Affordable Care Act is cited as a driving force in the growth of larger multi-hospital enterprises.3-5 There are competing theories regarding motivations and likely outcomes of this trend toward larger multi-hospital systems.6-8 One view is that hospitals join larger multi-hospital systems to serve larger populations more efficiently and to focus on population health management to improve outcomes and reduce costs. A competing view is that by consolidating into larger multi-hospital systems, it becomes virtually impossible for health plans to develop insurance products without including at least some of the system’s member hospitals in their preferred contracted networks—so-called must-have hospitals. When this occurs, the system gains leverage to negotiate contracts with health plans on an “all-or-none” basis, requiring the plan to include all system member hospitals in the plan’s preferred networks, regardless of their prices (or quality) relative to other potential substitutes in the market.9,10 This could result in higher prices to health plans and higher health insurance premiums to consumers.

This paper examines hospital prices in California over time (2004-2013) with a focus on hospitals in the largest multi-hospital systems. Our data show that hospital prices in California grew substantially (+76% per hospital admission) across all hospitals and all services between 2004 and 2013 and that prices at hospitals that are part of largest, multi-hospital systems grew substantially more (+113%) than prices paid to all other California hospitals (70%). Prices were similar in both groups at the start of the period (approximately $9200 per admission). By the end of the period, prices at hospitals in the largest systems exceeded prices at other California hospitals by almost $4000 per patient admission.

Our study findings are potentially useful to policy makers across the country for several reasons. First, we track actual prices (as opposed to billed charges11 or aggregate prices cited in other pricing studies) for a large sample of hospitals over a long period of time (10 years). In addition, California experienced its wave of consolidation much earlier than the rest of the country and as such California’s experience with large hospital systems may provide some insights into what may happen across the United States from hospital consolidation including growth of large, multi-hospital systems now forming in the rest of the country.

Data and Methods

Hospital price and utilization data (2004-2013) were provided by Blue Shield of California, one of the largest commercial health plans with coverage throughout the state of California. Prices represent the amounts actually approved for payment (as opposed to billed charges). Data on hospital characteristics are from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) weights, hospital wage index).

For each hospital, the average price (allowed payment) per day and per admission is calculated for all services. Hospital-level average prices are calculated for each hospital for 2-year periods beginning in 2004 and across all hospitals in the sample (n = 230 in 2012 and is relatively stable over time). Prices are calculated separately for hospitals that are members of the 2 largest, multi-hospital systems and compared with all other hospitals. Data from California Office of Statewide Health Planning Development (OSHPD) are used to identify hospital members of the 2 largest multi-hospital systems (Dignity Health, previously Catholic Healthcare West, and Sutter Health). The number of hospitals in each of these 2 systems has remained relatively constant throughout the study period (Dignity Health = 32, Sutter Health = 25 in 2012 out of 320 hospitals statewide). The member hospitals in these 2 systems are quite diverse: ranging in size from under 50 beds to over 700 beds, urban and rural, trauma and non-trauma status, and serving a varying range of commercial and low income populations.

Regression Analysis

Hospital prices grew faster for hospitals in the 2 largest systems compared with all other hospitals. We constructed a regression model to test for the possibility that greater price increases observed in hospitals in the largest, multi-hospital systems relative to all other hospitals are driven by the characteristics of the hospitals in large systems separately from their membership in a large hospital system. For example, hospitals facing less competition may have higher price increases even if they were not part of a large hospital system. The regression model was applied to all hospitals to control for membership in a large system and other factors hypothesized to affect hospital prices separately from membership in a large hospital system including hospital ownership and type (for-profit, district, teaching, rural, trauma), total beds (log), payor mix (disproportionate share hospital, percent total admissions commercial payors), percent total admissions through emergency room (ER), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) wage index, and local market competition (measured by a hospital specific Herfindahl-Hirschman Index).12,13 Time dummy variables are included to capture industry-wide effects of new technology, quality, and other changes than may have occurred during the study period affecting all hospitals. Inpatient prices are measured as the allowed amount per admission divided by the DRG weight. All measures are calculated at the hospital level and averaged over 2-year periods. The regression analysis was conducted twice. Model 1 includes only time trends and indicator variables interacted with time for hospitals that are members of the largest systems. Model 2 includes these same measures plus all the control variables. We compare the estimated coefficients for indicator variables for hospitals that are members of the largest systems (interacted with time) between the 2 models to determine the extent to which other factors explain and therefore reduce the substantial difference in price trends between the 2 groups.

Results

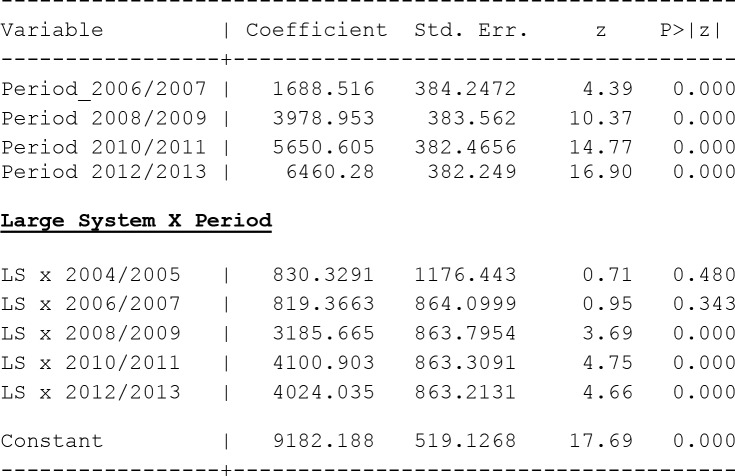

Hospital prices per day and per admission (Figure 1) grew substantially across all hospitals. Between 2004-2005 and 2012-2013, average per day prices across all hospitals, for all services grew from $3277 to $5735 (75%) whereas average per admission prices across all hospitals grew from $10 113 to $17 818 (76%). These price increases occurred during a period that included the great recession, and, during which, other economic indicators grew at moderate rates: California household income grew by 23% and inflation (urban consumer price index) grew by 24%. A review of detailed price trend data for homogeneous service categories (not shown here) such as maternity, surgery, medical, and so forth show price increases were generally similar across all services.

Figure 1.

Payment per admission and per day, 2004-2013.

Source. BSCA hospital claims data.

Note. Nominal prices. BSCA = Blue Shield of California.

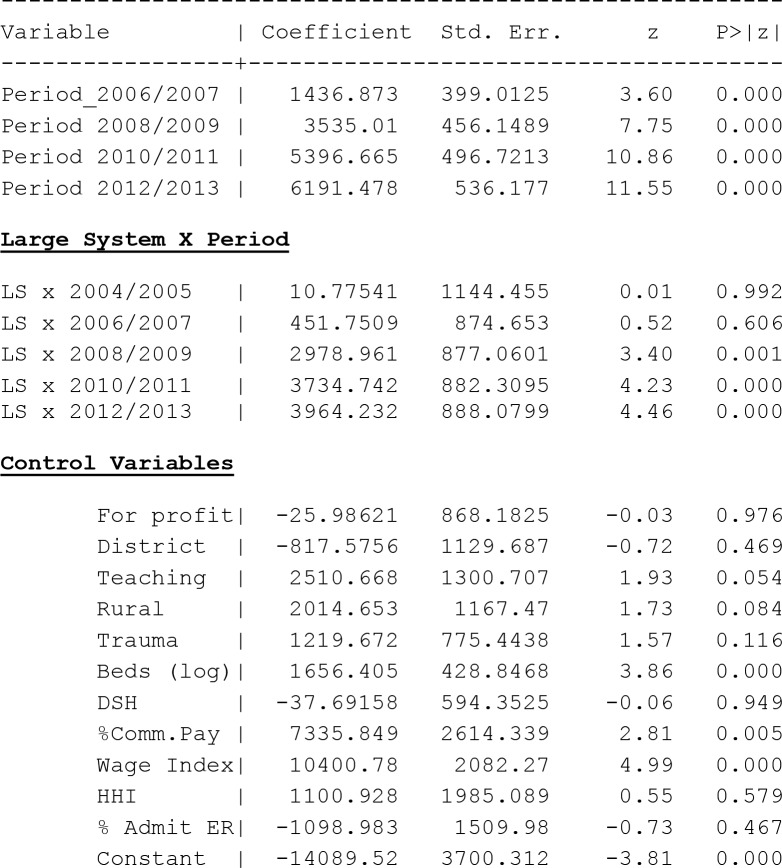

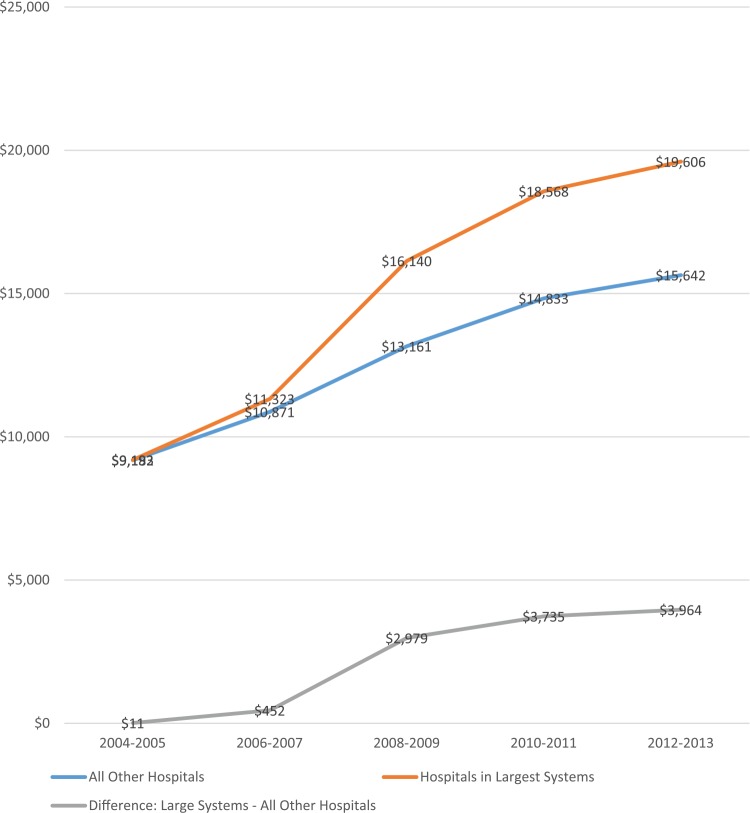

Figures 2 and 3 show the results for regression models 1 and 2. Model 1 (includes only time trends and indicator variables over time for hospitals that are members of the largest systems) results show a clear upward price trend over time above for hospitals in the largest systems compared with all other hospitals. Model 2 (includes the same measures as model 1 plus the control variables) results confirm the upward price trends for hospitals in large system hospitals substantially exceeding all other hospitals.

Figure 2.

Model 1: Estimated differences (nominal) in payment per admission between large system hospitals and all other hospitals, 2004-2013.

Figure 3.

Model 2: Estimated differences (adjusted) in payment per admission between large system hospitals and all other hospitals, 2004-2013.

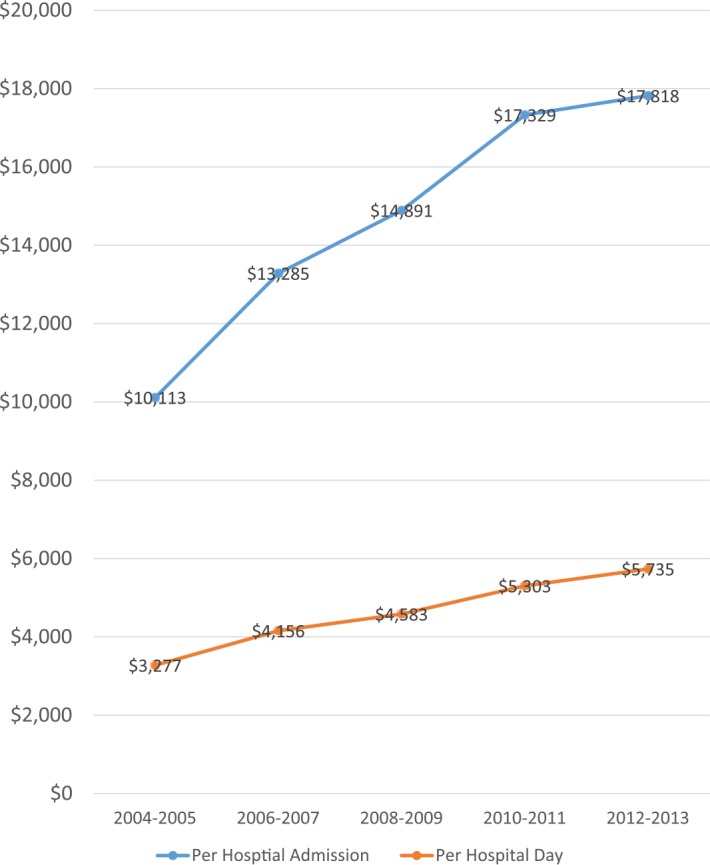

Figure 4 graphs the trends in price per admission using the results from Model 2 to compare hospitals in large systems with all other hospitals, controlling for other factors that might affect prices. Prices started (in 2004-2005) at about the same level for both groups of hospitals, (approximately $9200 per admission), and, though prices in both groups grew over time, prices at hospitals in the largest, multi-hospital systems grew much more rapidly than prices in all other hospitals. The cumulative difference in the growth of prices between the 2 groups is substantial—prices at hospitals in the largest systems increased 113% compared with 70% price growth in all other hospitals in California. These trends created an ever widening and substantial price differential over time—by 2012-2013 prices at hospitals in the largest systems exceeded prices in other hospitals by $3964 (25%), even after controlling for other factors.

Figure 4.

Payment per admission: Hospitals in largest multi-hospital systems versus all other hospitals (controlling for other factors), 2004-2013.

Source. BSCA hospital claims data.

Note. Payment amounts are adjusted for differences in between groups within each year based on regression coefficients in Figures 2 and 3. BSCA = Blue Shield of California.

Discussion

California has a long track record of hospital consolidation into multi-hospital systems—almost half of all hospitals have been in a multi-hospital system since 2004, with the 2 largest systems controlling almost 60 hospitals. Multi-hospital systems form, ostensibly, to increase efficiency and quality and to control cost and price increases. Yet, our data, from a very large commercial payor, show that hospital prices across all hospitals have increased substantially in California during a period of low overall price inflation, low economic growth, and declining demand for inpatient care (commercial volume declined, −566 032 adjusted inpatient days [−15%] between 2004 and 2012, OSHPD).

A potentially more troubling trend, however, is the substantially greater price increases observed in hospitals that are members of California’s largest, multi-hospital systems—average prices grew 113% in hospitals in the 2 largest systems compared with 70% growth in all other hospitals. It is important to note that this substantial price differential is not driven by other factors such as case mix, payor mix, and changes in local wage costs and local market competition, or other hospital characteristics. We found that prices in hospitals that are members of the largest multi-hospital systems are more than 20% higher by the end of the study period when compared with other hospitals after controlling for a wide range of factors.

The substantial difference in prices between hospitals in the largest multi-hospital systems and all other hospitals is consistent with a model that suggests that hospitals in large multi-hospital systems, by tying their hospitals together using “all-or-none” contracting, are able to achieve market power over prices beyond any local market advantages. A further potential danger is that with large size comes the potential to expand and protect market power. Large hospital systems that conduct “all-or-none” contracting have reportedly added other anti-competitive language to their contracts to protect and expand their market power including clauses that prohibit health plans or employers from developing “tiered” benefit packages that would allow them to accept the “all-or-none” demands to include all system hospitals in contracted networks but at the same time develop new products to stimulate competition through differential cost sharing across member hospitals.13-17 Another example is so-called gag-clauses which prohibit health plans from sharing detailed hospital specific utilization and pricing data with large employers which might be used to develop benefit packages that provide incentives for employees to use lower priced (and/or higher quality) hospitals.18,19

Conclusion

Our high-quality pricing data paint a potentially troubling picture both for California and the rest of the country. Hospital prices increased substantially during a period of slow economic growth and may have been driven in part by increased market power by large, multi-hospital systems (and possibly other smaller systems) practicing “all-or-none” contracting. If this interpretation is correct, there are several important lessons for policy makers across the country as they face decisions regarding consolidation. First, our regression findings suggest that the market power effects of large hospital systems do not necessarily require consolidation between local competitors. Indeed, many of the hospitals in California’s largest systems do not have substantial overlapping markets with other system member hospitals. This suggests that hospitals in large hospital systems, by tying their hospitals together, are able to achieve market power over prices beyond any local market advantages.

It is important to note that we have not controlled explicitly for differences between large system hospitals and other hospitals with regard to quality and technology differences and other factors such as financial status of hospitals or that hospitals that joined the largest systems may be different in some other unmeasured way. While model 2 does not include explicit measures of hospital quality due to the absence of quality data for earlier time periods, quality data are available covering years at the end of the study period and these data show minimal effects on price differences between the 2 groups of hospitals. IN addition, our analyses only cover systems within a single state and not multi-state systems. Further research is needed to address these issues and to more precisely control for other potential price related factors.

However, policy makers at both the federal and state levels might consider the potential lessons from California as we await further research as they develop policies to shape a more cost-effective health care system in an era of consolidation. Specifically, policy makers could consider limiting “all-or-none” contracting by multi-hospital systems and prohibiting other anti-competitive contract language that flows from market power achieved by large multi-hospital systems.20 Such pro-competitive regulation would allow for hospital systems to integrate to improve efficiencies without the deleterious side effects of increased market power which can result in reduced price competition and higher costs to consumers.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by USC Center for Health Financing, Policy, and Management.

References

- 1. Boulton G. Wave of consolidation engulfing health care systems. Journal Sentinel. http://www.jsonline.com/business/wave-of-consolidation-engulfing-health-care-systems-b99474527z1-298731631.html. Published April 5, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- 2. Creswell J, Abelson R. New laws and rising costs create a surge of supersizing hospitals. The New York Times. August 12, 2013:13. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lineen J. Hospital consolidation: “safety in numbers” strategy prevails in preparation for a value-based marketplace. J Healthc Manag. 2014;59(5):315-317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Knowledge @ Wharton. Hospital consolidation: can it work this time? Knowledge @ Wharton, Wharton University of Pennsylvania; knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/hospital-consolidation-can-it-work-this-time/. Published May 11, 2015. Accessed May 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dafny L. Hospital industry consolidation—still more to come? N Engl J Med. 2014;370(3):198-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frakt AB. Hospital consolidation isn’t the key to lowering costs and raising quality. JAMA. 2015;313(4):345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Davis K. Hospital mergers can lower costs and improve medical care: stand-alone hospitals have too few patients to thrive in the new era of population health management. Wall Street Journal. http://www.wsj.com/articles/kenneth-l-davis-hospital-mergers-can-lower-costs-and-improve-medical-care-1410823048. Published September 15, 2014. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- 9. Berenson RA, Ginsburg PB, Christianson JB, Yee T. The growing power of some providers to win steep payment increases from insurers suggests policy remedies may be needed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(5):973-981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lewis MS, Pflum KE. Hospital systems and bargaining power: evidence from out-of-market acquisitions. http://www.clemson.edu/economics/faculty/lewis/Research/Lewis_Pflum_hosp_bp.pdf. Published October 26, 2015.

- 11. Bai G, Anderson GF. Extreme markup: the fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keeler EB, Melnick G, Zwanziger J. The changing effects of competition on non-profit and for-profit hospital pricing behavior. J Health Econ. 1999;18(1):69-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Melnick G, Keeler E, Zwanziger J. Market power and hospital pricing: are nonprofits different? Health Aff (Millwood). 1999;18(3):167-173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. California Healthline. MCOs to introduce “network-within-a-network” plans featuring steep copays for certain hospitals. California Healthline Daily Edition. http://californiahealthline.org/morning-breakout/mcos-to-introduce-networkwithinanetwork-plans-featuring-steep-copays-for-certain-hospitals/. Published October 24, 2001. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- 15. Colliver V. Insurers seeking higher co-pays for certain hospitals. San Francisco Chronicle, Physicians for a National Health Program; http://www.pnhp.org/news/2002/january/insurers-seeking-higher-co-pays-for-certain-hospitals. Published January 31, 2002. Accessed May 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee D. Blue cross backs off “tiered hospital” idea. Los Angeles Times. 2002;1. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bailey E, de Brantes F, DiLorenzo J, Eccleston S. HCI3 improving incentives issue brief: tracking transformation in US health care. Health Care Incentives. http://www.hci3.org/wp-content/uploads/files/files/HCI-IssueBrief-Jan13-L7.pdf. Published January 2013. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- 18. Rauber C. Sutter hides health costs: legislation seeks to remove gag clauses. San Francisco Business Times. http://www.bizjournals.com/sanfrancisco/stories/2008/03/10/story2.html. Published March 7, 2008.

- 19. Catholic Healthcare West. Blue Cross of California and CHW reach agreement on multi-year contract: coverage continues uninterrupted for Blue Cross members at CHW hospitals. PR Newswire. http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/blue-cross-of-california–catholic-healthcare-west-reach-agreement-on-multi-year-contract-72883087.html. Published August 15, 2000. Accessed May 10, 2016.

- 20. United States. Cong. House. Committee on House Senate. Health Care Mergers, Acquisitions, and Collaborations, 2015-2016, SB-932. LegInfo.Legislature.ca.gov. California Legislative Information; https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB932. Published February 1, 2016. Accessed May 10, 2016. [Google Scholar]