Abstract

Increasing child vaccination coverage to 85% or more in rural India from the current level of 50% holds great promise for reducing infant and child mortality and improving health of children. We have tested a novel strategy called Rural Effective Affordable Comprehensive Health Care (REACH) in a rural population of more than 300 000 in Rajasthan and succeeded in achieving full immunization coverage of 88.7% among children aged 12 to 23 months in a short span of less than 2 years. The REACH strategy was first developed and successfully implemented in a demonstration project by SHARE INDIA in Medchal region of Andhra Pradesh, and was then replicated in Rajgarh block of Rajasthan in cooperation with Bhoruka Charitable Trust (private partners of Integrated Child Development Services and National Rural Health Mission health workers in Rajgarh). The success of the REACH strategy in both Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan suggests that it could be successfully adopted as a model to enhance vaccination coverage dramatically in other areas of rural India.

Keywords: immunization, computer database, REACH strategy, India, child health, government, intervention study

Introduction

Child immunization is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions. Reports indicate a remarkable reduction in child mortality in countries with poorest child survival indicators following the introduction of immunization against vaccine preventable diseases.1 The examples of Chad (a country with one of the lowest vaccination rates) and Cambodia (with high measles mortality and poor immunization coverage) making firm strides to achieve the Millennium Development Goal 4 (MDG-4) of reducing under-five mortality through improved access to immunization reinforce the importance of implementing strong measures for improving coverage translating to overall development.2,3 However, it has been explicitly stated that a large population in middle-income countries, including India, has inadequate access to immunization accounting for low coverage.4 The reasons attributed for this are many, whereby large implementation costs has been cited as the most important factor. To address these reported gaps, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation announced the Decade of Vaccines to support issues related to poor vaccine delivery in countries.5

Owing to insufficient economic capacity to immunize her 120 million under-five children, India, the second most populous country of the world received 130 million US dollars (US$) since 2002 from the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) to improve immunization coverage.6 Yet, despite the concerted efforts of the Central and State governments and other voluntary agencies, immunization rates in India remain low.7 According to the national immunization schedule (Table 1), all primary immunizations should be completed by the time a child is 12 months old. For the calculation of vaccine coverage rates, the number of children in the age group of 12 to 23 months is taken as the denominator, because these children should have received all primary immunizations. Hence, children aged 12 to 23 months who received Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG), 3 doses each of Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus (DPT) and Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) (excluding OPV dose 0), and measles vaccine are considered to be fully immunized. This procedure was followed by National Family Health Survey (NFHS)8 in its different waves to work out immunization coverage rates by vaccine. Immunization coverage rates reported by NFHS-38 (2005-2006) were as follows: all India 44.0% (rural 39.0%), Andhra Pradesh 46.0% (rural 43.0%), and Rajasthan 26.5% (rural 22.1%). There was a wide variation in immunization coverage rates among Indian states, and states with low immunization coverage had higher child mortality rates.7

Table 1.

Primary Vaccination Schedule Under the Universal Immunization Program in India.

| Vaccine name and dose | Age when given |

|---|---|

| BCG, OPV dose 0 | At birth |

| DPT dose 1, OPV dose 1 | 6 wk |

| DPT dose 2, OPV dose 2 | 10 wk |

| DPT dose 3, OPV dose 3 | 14 wk |

| Measles | 9 mo |

Note. BCG = Bacille Calmette-Guerin; OPV = Oral Polio Vaccine; DPT = Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus.

Science Health Allied Research Education (SHARE) INDIA, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) from Andhra Pradesh, India, developed a strategy called Rural Effective Affordable Comprehensive Health Care (REACH) with the primary objective of promoting antenatal care, child immunization, and family planning. The REACH model, which was implemented in all 40 villages in Medchal mandal of Andhra Pradesh in 1994, had achieved full immunization coverage of 96% among children aged 12 to 23 months in 2007.9 The REACH strategy comprised a 3-tier system where each village was mapped by global positioning system (GPS), and surveyed, along with enumeration of all persons in the household. Health information was gathered by well-trained community health volunteers (CHVs), 1 per 200 households, whose work was closely supervised by 4 health supervisors and 2 field coordinators. Villagers’ demographic profiles and health data, including data on pregnant women, were tracked by a computer database. This was used to generate timely information for health care interventions and weekly reports of unimmunized children (using pregnancy and delivery tracking) in each village. It was shared with government health functionaries to target all unimmunized children. However, if government workers failed to immunize all identified children, the REACH health supervisors provided appropriate immunizations. This pilot project proved to be successful in immunizing 96% of the children in the area.9 Despite the success of the REACH strategy, we felt it might not be affordable to implement in other regions, as the original pilot required hiring NGO health workers in parallel with government functionaries. To render this strategy widely applicable, it was felt necessary to test its efficacy without deploying NGO health workers.

Bhoruka Charitable Trust (BCT), which operated Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) Scheme in partnership with the government for 18 years in Rajgarh block of Rajasthan, India, provided us a unique opportunity to test the REACH strategy without recruiting additional NGO health workers. It only required BCT to supplement its ongoing efforts with computerized data in REACH format. This innovative strategy was designed to test whether a higher immunization level could be achieved with minimal additional staff. Our objective was to test whether full immunization coverage of at least 85% could be achieved in interior villages, by upscaling the REACH strategy and utilizing only government functionaries, supplemented by a minimal data management staff.

Methods

Study Setting

The study was conducted in Rajgarh block of Churu district in Rajasthan, India, during 2008-2009. The study area was located in latitude and longitude 75°E and 28°N, respectively. The block had a population of 309 481 living in 53 163 households in 225 villages administered by 55 Panchayats (or village local governance). The village population ranged between 100 and 7000. The proportion of male children was 54.4% and females 45.5%. The child sex ratio was 837 females per 1000 males. The Rajgarh town population was not included in this project because they had adequate medical facilities. Overall, Rajasthan was among the 7 North Indian states with none of the districts having >80% DPT coverage in 2002-2003. All districts had poor DPT dose 3 coverage (approximately 30%).10 Health services were provided by the ICDS Scheme and National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) health staff that included a child development project officer (CDPO), 12 lady health supervisors (LHSs), 81 auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs), 274 anganwadi workers (AWWs), and 250 accredited social health activists (ASHAs).

Status of Immunization

The NFHS-3 reported full immunization rate to be 22.1% for rural areas among sampled population in Rajasthan in 2005-2006.8 In 2008, BCT engaged the services of Indian Institute of Health Management Research (IIHMR), Jaipur, Rajasthan, to carry out an independent baseline evaluation of ICDS services in the Rajgarh block by conducting a 30-cluster survey, which showed a full immunization rate of 64.7% among 12- to 23-month-old children of Rajgarh block. The same survey also found that 32.4% children were partially immunized and 2.9% did not receive any immunization.11 These results constituted the benchmark for evaluating the effectiveness of the REACH strategy in augmenting immunization coverage in the study area. The District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS)-3 of 2007-2008 reported a full immunization rate of 38.8% for Churu district and 48.7% for the entire state of Rajasthan.12 The dropout rates were also shown to be high for all vaccines in all the surveys.

Survey Instruments

Household questionnaire was used to list all residents in the household on the day of survey. It yielded information on sociodemographic characteristics; prevalence of common health problems including asthma, tuberculosis, diabetes, goiter, malaria, and jaundice; and addictions including tobacco, alcohol, and smoking. It also yielded information on household condition, lighting source, cooking fuel, and ownership of livestock and agricultural land.

The women’s questionnaire was designed to collect information from all currently married women of age 15 to 49 years residing in the households. Information was obtained on the background characteristics of women, their reproductive history, contraceptive use, antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care, child immunizations and child health, and utilization of ICDS services.

Implementation

To implement and test the REACH strategy, BCT provided data management staff consisting of 1 field supervisor, 1 data manager, and 5 data entry operators, along with a computer server with 5 nodes and a printer.

Household survey was conducted by ASHAs in REACH format. One round of survey was conducted in 2008 on the entire rural population of Rajgarh block to include all beneficiaries in the area. A second follow-up was done to update survey data on missing beneficiaries after 30 days of the initial survey. The survey findings were used to create a computerized database. Information from the women’s questionnaire was used to identify the pregnant women and immunization status of children in the villages. Monthly reports were generated for identifying children due for immunization, but not yet immunized. These reports were provided to the LHSs 2 weeks ahead of the monthly sector meetings for distribution to the ASHAs at monthly sector meetings. The ASHAs were asked to ensure the immunization of unimmunized children in the list with the help of ANMs. ASHAs submitted reports of immunizations conducted and additional information regarding new pregnancies and live births in their service areas. At monthly sector meetings, the field coordinator received these updated reports from ASHAs through the LHSs. LHSs were expected to verify completeness and accuracy of collected data before submitting it to the field coordinator. Data were entered into the computer to maintain a prospective database in time for making available revised immunization lists to LHSs and ASHAs within 2 weeks.

The REACH Software and Data Quality

We used Visual Basic 6v as frontend for data entry and MySQL 5.01v as backend (database). For generating reports (automation of eligible children), Crystal Reports 7.0v was used. The survey and follow-up data on currently pregnant women were entered in the software that tracked each woman till delivery and after. Alert reports for children due for the respective dose of vaccination with a colored dose date box that the ANMs found easy to use were thus generated. Follow-up details of vaccinated and unvaccinated children could be updated in the software.

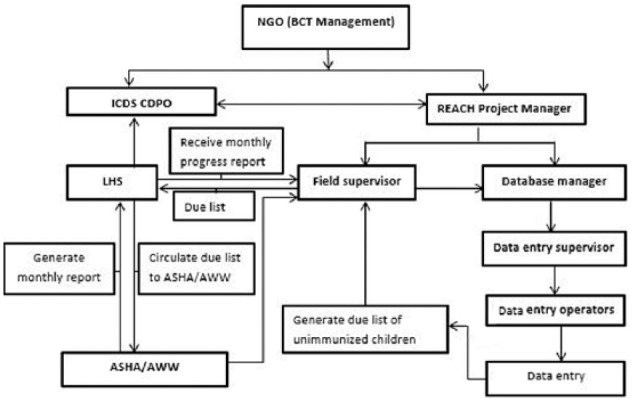

A field coordinator cross-checked the field data received from the ASHA/LHS. It was then given to the statistician who checked for inconsistencies, and then given to the data manager. The data manager ensured quality that the data were adequate and responsible for oversight of high-quality data entry (Figure 1). For each entry, the data entry person looked at the family tree so that total family details were correctly entered in the system. The statistician and data manager ran the demographic data frequencies and checks to ascertain completeness and ensure quality of entered data. The data entry person received 1-month training, while the data manager received it for 2 months to implement the software.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of REACH organization and data acquisition.

Note. REACH = Rural Effective Affordable Comprehensive Health Care; NGO = nongovernmental organization; BCT = Bhoruka Charitable Trust; ICDS = Integrated Child Development Services; CDPO = Child Development Project Officer; LHS = lady health supervisor; ASHA = accredited social health activist; AWW = anganwadi worker.

The use of computerized data was initiated in October 2008. All pertinent data as of December 31, 2009, relating to immunization services during this period were analyzed.

Ethical Approval

The institutional ethics committee of SHARE INDIA MediCiti Institute of Medical Sciences provided the ethical approval for the study.

Results

About 14 months after initiation of the REACH strategy, full immunization coverage increased dramatically to 88.7%, partial immunization declined to 10.3%, and only 1.0% did not receive any immunization, compared with the results of the benchmark IIHMR survey (2008) to represent the preintervention rates. The coverage rates of individual vaccines were similar to the percentage of children fully immunized; 97.2% of the children had received BCG, 95.1% of the children had received 3 doses each of DPT and OPV, and immunization against measles had been received by 89.2% of children. Gender differentials in immunization coverage rates by vaccine were found to be negligible (Table 2). By the end of 2009, this model was further expanded to 2 more adjoining rural areas. Overall, 91.3% children were fully immunized, 6.3% were partially immunized, and remaining 2.4% were unimmunized.

Table 2.

Percentage of Children Age 12 to 23 Months Who Received Specific Immunization, Rajgarh Block, Rajasthan, 2008-2009.

| Vaccine | Male (n = 2703) | Female (n = 2304) | Total (n = 5007) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCG (n = 4894) | 97.3 | 97.0 | 97.2 |

| OPV dose 1 (n = 4889) | 97.3 | 96.8 | 97.1 |

| OPV dose 2 (n = 4848) | 96.7 | 95.7 | 96.2 |

| OPV dose 3 (n = 4802) | 95.5 | 94.5 | 95.1 |

| DPT dose 1 (n = 4889) | 97.3 | 96.8 | 97.1 |

| DPT dose 2 (n = 4848) | 96.7 | 95.7 | 96.2 |

| DPT dose 3 (n = 4802) | 95.5 | 94.5 | 95.1 |

| Measles (n = 4617) | 89.6 | 88.8 | 89.2 |

| Fully immunized (received all vaccines) | 89.1 | 88.2 | 88.7 |

Note. BCG = Bacille Calmette-Guerin; OPV = Oral Polio Vaccine; DPT = Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus.

Dropout rate was calculated between DPT dose 1 and dose 3, as well as between DPT dose 1 and measles. The dropout rate between the first and third doses of DPT was 1.8%. Dropout rate between DPT dose 1 and measles was 5.6%. BCG to measles dropout was 5.6% while DPT dose 3 to measles dropout was 3.8%.

Discussion

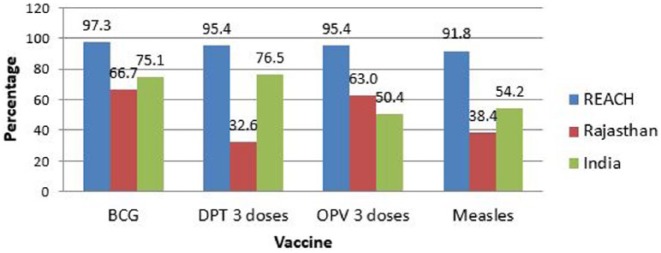

The key factors tested in this study were (1) our ability to upscale the REACH strategy and computer database and (2) its success using only Government health functionaries in very remote villages. We were encouraged by the observation that over 85% full immunization could be achieved in Rajgarh block in a short period of 14 months. This increase was 62 percentage points higher than the rate of 27% for the entire state of Rajasthan13 and more than twice the rate in rural India (39%) as reported by NFHS-3 (2008) in 2005-20068 (Figure 2). When compared with the baseline data from the IIHMR evaluation survey in 2008,11 implementation of the REACH strategy improved full immunization coverage by 24 percentage points while partial immunization was reduced by 26.1 percentage points. The more recent NFHS-4 (2015-16)14 also reported lower rates (58.6% for rural areas in Churu district) when compared with our model. As NFHS-3 data referred to the entire State of Rajasthan for the period 2005-2006, they were not comparable with the data for Rajgarh block. On the contrary, IIHMR data were comparable for studying the impact of REACH strategy in augmenting immunization coverage. Regardless of whichever baseline data were taken for comparison, implementation of the REACH model has the potential to significantly augment full immunization coverage in a short span of time.

Figure 2.

Coverage of individual vaccines among 12- to 23-month children in REACH villages, rural Rajasthan, and India.

Note. REACH = Rural Effective Affordable Comprehensive Health Care; BCG = Bacille Calmette-Guerin; DPT = Diphtheria-Pertussis-Tetanus; OPV = Oral Polio Vaccine.

Our model performed much better in comparison with other individual reports. Jain15 surveyed the rural population of Alwar district in Rajasthan and reported 29% of the children aged 12 to 35 months being fully immunized with BCG, 3 doses of DPT, 3 doses of OPV, and measles vaccines. He found 26.5% not immunized, 44.5% to be partially immunized; and a high dropout rate with about one-third of children dropping out of the third dose of DPT and OPV, which was considerably higher compared with our findings. We found the dropout rates to be much lower at about 1.8% between the first and third doses of DPT. The dropout between DPT dose 1 and measles was also low using our strategy. The low dropout rates in our model imply the absence of access and utilization problems. This may be attributed to the timeliness and door-to-door service for children with missed vaccine doses. In addition, the low dropout rates reflected the good quality of communication by the health workers and overall perceived quality of service in community to be satisfactory.16

Various reasons for high partial/nonimmunization rates in the study area have been reported in literature. A survey conducted by IIHMR in the study area in 2007-2008 (the same year as REACH baseline survey) found that multiple reasons for partially or not immunizing the children included inadequate information about complete immunization schedule (64.7%), thinking immunization was not required (4.2%), no faith in immunization (1.4%), lack of time to take children to immunization sessions (2.8%), and sick child (1.4%).17 Organizational problems were reported to be major in this survey with 8.3% parents reporting nonexistence of immunization services at the center, 20.8% reporting absence of health workers, and 4.2% reporting no immunization session being conducted on respective dates.17 A United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) report after interviewing over 10 000 mothers, exploring the same reasons, categorized them into demand-side and supply-side problems. The former included not feeling need (45.3%), no knowledge about vaccine (20.4%), no knowledge about place of vaccination (17.6%), inconvenient time (9.4%), fear of side effects (5.3%), and other similar reasons, while the latter included nonavailability of vaccine (5.9%), service (4.5%), or service provider (4.9%) as major reasons among others.18 International studies on reasons for partial and nonvaccinations have given a framework of the following categories of related factors: immunization system, communication and information, family characteristics and parental attitudes, and knowledge wherein factors related to immunization system, including distance (49 studies), poor health staff motivation (49 studies), lack of resources (48 studies), false contraindications (47 studies), unreliability (34 studies), and others, as well as poor parental attitude and knowledge including lack of knowledge (58 studies), fear of side effects (47 studies), conflicting priorities (43 studies), cultural beliefs (41 studies), low perceived importance of vaccinations (30 studies), and similar reasons, have been shown to be the major contributor for partial/nonimmunization worldwide including India.19,20 The proportion of partial/nonvaccinated children in our study remained low at the end of 1 year, although similar factors operated in the present study area as well.

We have not come across any other published materials on the use of computerized databases for achieving enhanced immunization rates in India during our study period. The State Government of Rajasthan, of late, mandated the electronic health and e-governance reform in maintaining online data of more than 13 000 government health institutions in the state, and monitoring a birth cohort of over 1 million children each year providing key information to health officials and demographers. This model, although not free of operational problems, uses patient tracking and digital community engagement to improve coverage of basic health services.21 Prior to this, several isolated m-health related and unrelated strategies were experimented that showed a modest increase in immunization coverage rates. A lentil-based incentive program implemented by an NGO in remote villages of Udaipur reported an increase in full immunization rates to 60% from a baseline of 23%.22 In another experiment, data from tracking immunization records of children under the age of 1 were collected on a wearable mobile health platform in decentralized, connectivity-independent manner.23 The device stored immunization records digitally on a Near Field Communication (NFC chip), which could be both read and updated by a custom Android smartphone application used by the community health worker instead of the traditional register, thereby offering the advantage of data digitization and decentralization at the point of care, ultimately increasing the full immunization coverage rates. In Bangladesh, the Gates Foundation Vaccine Innovation Award was bestowed on Dr Asm Amjad Hossain, who increased the immunization rates by 15 percentage points in 2 districts (Brahmanbaria and Habiganj), by using computers for tracking pregnant mothers, providing immunization schedules, instituting increased accountability for health workers, and providing vaccinators’ phone numbers on children’s immunization cards.24 The success of our experiment and that of Dr Hossain suggests that relevant, high-quality computerized health metrics are critical for improving the effectiveness of field health workers. We believe that regularly updated lists of children to be vaccinated constitute the most useful tool. In addition, such lists assist supervisors of field workers to improve accountability. Appropriate timely information leads to accountability and effectiveness.

The average cost of vaccinating a child is approximately 22.50 US$.25 A marginal increase in cost was incurred for computerizing survey data and generating reports of unimmunized children on a regular basis. This increase may be <2% of the total cost of immunization services. We feel the benefits achieved far outweighed the marginal increase in costs. A research study estimated that deaths due to DPT may be reduced by 1000 to 3000 from the current levels varying within states if immunization coverage is increased to 90%, while those from measles may reduce by 2000 to 6000. In the wake of adding rotavirus vaccination to the Universal Immunization Program (UIP) of India from 2016, the gains estimated (for baseline DPT at 76.8% coverage) are averting 34.7 (95% uncertainty range [UR], 31.7-37.7) deaths and 995 (95% UR, 910-1081) disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100 000 under-fives per year, approximately amounting to 44 500 deaths and 1.28 million DALYs throughout the country. It has further been projected that if immunization coverage increases to 90% for rotavirus, the benefit would be increased, further reducing 22.1 deaths (95% UR, 18.6-25.7) per 100 000 under-fives and 630 (95% UR, 522-737) DALYs per 100 000 additionally for all of the related diseases.25 The treatment costs averted following rotavirus vaccination in India are estimated to be 21 million US$.6 The health and economic benefits of increasing measles vaccination coverage under the Decade of Vaccines initiative have been projected to averting 0.3 million deaths and 11.9 million cases globally, while averting costs approximating 9656 million US$ (in 2009) including treatment costs, caretaker productivity, and death productivity. These cost benefits are higher for pertussis and other vaccines.5 In addition, strong vaccination programs with annual returns (on vaccine investments) ranging from 12% to 18% have also been essentially associated with extending life expectancy, promoting women empowerment, enhancing mobility, and promoting peace, equity, and economic development.26 A recent study using 2012 data, while recommending addition of 3 newer vaccines to UIP and proposing a scaling up to 90%, projected an estimated annual social and economic benefit of 9.1 US$ annually for India.6 Our findings are, however, limited by the fact that we could not undertake a cost-benefit analysis of the REACH immunization program (Rajasthan) in our limited study duration of 2 years, although we expect similar benefits given the results achieved are sustainable. Our experience of REACH in Andhra Pradesh tells that the model has self-sustained for over 20 years.9 The model initially implemented in 1994, raised the full immunization rate among 698 children aged 12 to 23 months in rural Medchal mandal to 96% in 2007, and continued to sustain a high full immunization rate (92.1%) till 2014.

Some operational challenges are likely to occur when the model is implemented using government staff. First, the government staff receive salaries for their services from the state and may not be compelled by any other institution to deliver extra services. Second, most studies have found that the motivation levels of the government functionaries to be low due to various reasons.27 Third, the program operates on an incentive mode, wherein the government staff are given targets and incentivized for meeting them. Our model did not support this target-oriented approach. Furthermore, there is variable political commitment for particular health programs and heightened interest for some; the budgetary allocation varies accordingly, thus making immunization a high-investment program. The motivation of government functionaries to be sustained over the years for any program itself remains an enormous challenge given the burden of paperwork, travel, and additional workload of vacant positions.

An important limitation is this study is that we cannot conclusively state how much the REACH strategy increased immunization in Rajgarh block. While the database reports an initial figure of 88% children immunized, in-person surveys in early 2009 suggested that this was due to incomplete reporting of immunizations to ASHAs and LHSs, not due to failure to give immunizations. The final figure of 91.3% is more reliable, as by end-2009, substantial controls were in place to verify submitted data and all workers had practiced with the system.

The challenges faced while implementing the model in Rajgarh villages were many. Most importantly, we identified that poor follow-up and communication by government staff as the prime reason for high partial/nonimmunization and dropouts, although access was fairly moderate with 72.1% villages in Churu district having access to a subcenter within 3 km and 75% of the primary health centres (PHCs) functioning 24 hours.28 The listing of beneficiaries helped to mitigate this problem as the time spent on house-to-house survey for identification of unvaccinated children was saved for other activities and lessen the stress on the burdened health workers. This model particularly helped to track dropouts in multidose vaccines. The government functionaries also feared the additional reporting burden imposed to support implementation and data updating, but their apprehensions were allayed with short orientation training where they were explained not to collect additional data but to improve data collection quality on existing parameters. We also felt the need for periodic reorientation for boosting the dwindling motivation levels of health functionaries. Additional interfaces for better communication with beneficiaries may also be provided to break the user end resistance and improve coverage rates. Community participation and engagement strategies have been shown to boost immunization coverage rates in other similar performing regions.29 The software performed well with very few technical problems that were easily absolved by the data manager. Data entry staff and data manager were trained by internationally certified trainers from SHARE INDIA, who also desig-ned the software and piloted its implementation in Andhra Pradesh.

It is possible that government health functionaries can implement the REACH strategy without partnering with an NGO. We recommend that this possibility be field tested in some selected areas. The state government of Rajasthan has adopted the pregnant women tracking process in its current e-health and governance, thereby demonstrating the feasibility and success of the model in large populations.21 Although our database has been most successful with immunization programs, it may be helpful in other areas of public health as well. For example, REACH in Rajasthan has also been used to track antenatal care visits and delivery sites for pregnant women. It has also yielded data on family planning practices and trends.30

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that the REACH strategy can be adopted to achieve more than 85% full immunization coverage of children aged 12 to 23 months within 2 years in Indian villages by government health functionaries when supplemented by a small data management (NGO) staff. Whether the same results can be achieved without partnering with an NGO needs to be tested.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Bhoruka Charitable Trust, Rajasthan (India), provided logistics support in the form of computers and manpower support as data manager, field supervisor, and data entry operators. Research reported in this publication was conducted by scholars in the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health training program under award number D43 TW 009078.

ORCID iDs: Enakshi Ganguly  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1708-483X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1708-483X

Alik Widge  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8510-341X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8510-341X

References

- 1. Zuehlke E. Child Mortality Decreases Globally and Immunization Coverage Increases, Despite Unequal Access. Population Reference Bureau; 2009. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2009/childmortality.aspx. Accessed February 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. United Nations. We can end poverty: millennium development goals and beyond 2015. Factsheet. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/Goal_4_fs.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed February 2, 2016.

- 3. You D, Jones G, Hill K, Wardlaw T, Chopra M. Levels and trends in child mortality,1990-2009. Lancet. 2010;376:931-933. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61429-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization, United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund, The World Bank. State of the World’s Vaccines and Immunizations. 3rd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stack ML, Ozawa S, Bishai DM, et al. Estimated economic benefits during the “decade of vaccines” include treatment savings, gains in labor productivity. Health Aff. 2011;30(6):1021-1028. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mirelman AJ, Ozawa S, Grewal S. The economic and social benefits of childhood vaccinations in BRICS. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:454-456. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.132597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Immunization Handbook for Medical Officers. Guwahati: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. International Institute for Population Sciences and Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-06: Rajasthan. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tatineni A, Vijayaraghavan K, Reddy PS, Narendranath B, Reddy RP. Health metrics improve childhood immunisation coverage in a rural population of Andhra Pradesh. Indian J Public Health. 2009;53(1):41-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Multi Year Strategic Plan 2005-2010 Universal Immunization Programme. Guwahati: Department of Family Welfare, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 11. IIHMR report Bhoruka Charitable Trust and SHARE INDIA. REACH Annual Report 2009 Rajgarh Block, Churu District, Rajasthan. Rajasthan, India: Bhoruka Charitable Trust and SHARE INDIA, Andhra Pradesh; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12. International Institute for Population Sciences. District Level Household and Facility Survey (DLHS-3), 2007-08: India—Rajasthan. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Rural Health Mission Rajasthan State Report. Date unknown. http://mohfw.nic.in/NRHM/Documents/High_Focus_Reports/Rajasthan_Report.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2012.

- 14. International Institute for Population Sciences and ORC Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), India, 2015-16: Rajasthan. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jain SK, Chawla U, Gupta N, Gupta RS, Venkatesh S, Lal S. Child survival and safe motherhood program in Rajasthan. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73(1):43-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Immunization Module: Monitoring your Immunization Programme. Study session 10 monitoring your immunization programme. Date unknown. www.open.edu./openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=53371&printable=1. Accessed August 29, 2017.

- 17. Government of Rajasthan and Indian Institute of Health Management Research. Report on Short Programme Review on Child Health in Rajasthan. Jaipur, India: Directorate of Health and Medical Services, Government of Rajasthan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. National Factsheet: Coverage Evaluation Survey, 2009. New Delhi: UNICEF India Country Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Favin M, Steinglass R, Fields R, Banerjee K, Sawhney M. Why children are not vaccinated: a review of the grey literature. Int Health. 2012;4:229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rainey JJ, Watkins M, Ryman TK, Sandhu P, Bo A, Banerjee K. Reasons related to non-vaccination and under-vaccination of children in low and middle income countries: findings from a systematic review of the published literature, 1999-2009. Vaccine. 2011;29(46):8215-8221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Department of Medical, Health & Family Welfare, Government of Rajasthan. Pregnancy, Child Tracking & Health Services Management System. Version 8.2.4.16. http://pctsrajmedical.raj.nic.in/private/login.aspx. Published 2016. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- 22. Banerjee AV, Duflo E, Glennerster R, Kothari D. Improving immunisation coverage in rural India: clustered randomised controlled evaluation of immunisation campaigns with and without incentives. BMJ. 2010;340:c2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. IDEO. The Field Guide to Human Centered Design; 2015Canada: IDEO.org/ Design Kit; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. The gates notes. A hero in the battle against polio. http://www.thegatesnotes.com/Topics/Health/A-Hero-in-the-Battle-Against-Polio. Updated February 8, 2012. Accessed February 20, 2012.

- 25. Megiddo I, Colsona AR, Nandi A, et al. Analysis of the Universal Immunization Programme and introduction of a rotavirus vaccine in India with IndiaSim. Vaccine. 2014;32(suppl.):A151-A161. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Andre FE, Booy R, Bock HL, et al. Vaccination greatly reduces disease, disability, death and inequity worldwide. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:140-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tripathy JP, Goel S, Kumar AM. Measuring and understanding motivation among community health workers in rural health facilities in India—a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ORC Macro International. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), India, 2015-16: District Fact Sheet, Churu, Rajasthan. Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Johri M, Chandra D, Koné GK, et al. Interventions to increase immunization coverage among children 12-23 months of age in India through participatory learning and community engagement: pilot study for a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007972. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ganguly E. Supplementary role of health metrics for reducing total fertility rate in a North-Indian state. Online J Health Allied Sci. 2012;11(4):3 http://www.ojhas.org/issue44/2012-4-3.html. Accessed December 18, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]