Abstract

We analyzed what happens to a nursing home chain when private equity takes over, with regard to strategy, financial performance, and resident well-being. We conducted a longitudinal (2000-2012) case study of a large nursing home chain that triangulated qualitative and quantitative data from 5 different data sources. Results show that private equity owners continued and reinforced several strategies that were already put in place before the takeover, including a focus on keeping staffing levels low; the new owners added restructuring, rebranding, and investment strategies such as establishing new companies, where the nursing home chain served as an essential “launch customer.”

Keywords: nursing homes, private equity, strategy, staffing, care quality

Introduction

Private equity firms own and trade unlisted, private companies. A central investment strategy of private equity firms is the leveraged buyout (LBO), which is characterized by high leverage, large management ownership, and active corporate governance.1 In an LBO, the private equity firm creates a fund that obtains capital commitments from investors such as pension plans, insurance companies, and individuals. Using the fund’s capital, along with a loan commitment on behalf of the fund, the private equity firm acquires a so-called portfolio company and holds the portfolio company for approximately 3 to 7 years.2 During this period, it seeks to increase the value of the company, to realize a profit when it sells the company. The profits in case of such an “exit” are distributed among the fund investors and the private equity firm.3

In the past 2 decades, private equity interventions have been the issue of several public debates. Private equity opponents argue that the increased leverage in LBOs make firms short-term oriented. In addition, buyouts would often result in a redistribution of wealth from employees to investors.1,4-6 In contrast, proponents argue that the organizational changes in LBOs improve manager’s incentives to maximize value, leading to improved company performance.1

Since the 1990s, private equity firms regard the health care sector as an attractive investment area.7 The health care sector captures approximately 10% of the private equity deal activity worldwide, with providers and related services as the most popular sub sector (nearly 50% of the total health care deal volume). Providers and related services include large “healthcare-heavy assets,” the label private equity firms apply to “assets with meaningful exposure to reimbursement risk.”8 The involvement of private equity firms in health services fits into the global movement toward involving the private sector to attract capital and to deliver health services.9 Private equity in health services is most visible in the US nursing home industry, where 4 out of the 10 largest for-profit nursing home chains were purchased by a private equity firm in the 2003-2008 period.10 Moreover, in countries such as Canada, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, large for-profit nursing home chains are increasingly owned by private equity investors.11 It is therefore very relevant to study private equity in nursing homes.

Studies on private equity in US nursing homes show mixed outcomes. Pradhan et al12 reported that private equity-owned nursing homes show better financial performance than other for-profit nursing homes, while Cadigan et al13 found little impact of private investment purchases for the financial health. On staffing, Stevenson and Grabowski14 found reduced nursing home staffing after private equity transactions, but they reported that staffing levels were already decreasing prepurchase. Yet another study found lower staffing of registered nurses (RNs) in private equity-owned nursing homes.15 Harrington et al16 found no significant changes in staffing levels in the post–private equity purchase period, in part because staffing levels in large chains were already lower than staffing in other ownership groups in the prepurchase period. And while Stevenson and Grabowski14 reported no difference in quality, two other studies reported significantly higher levels of deficiencies after private equity purchases, being an indicator of worsened care quality.15,16 Another study showed that nursing homes that underwent chain-related transactions had more deficiency citations in the years preceding and following a transaction than those nursing homes that maintained common ownership.17

These mixed findings imply that outcomes may vary, depending on private equity owner’s strategies and contextual characteristics of individual portfolio companies. Scholars therefore stress that

[there is] a scarcity of cases reporting in any detail on the kind of restructuring that takes place in individual companies after they are acquired by private equity firms . . . There is a requirement for fine-grained research . . . at the micro level.18

They stress the need for “longitudinal studies that chart the development and impact of changes” during private equity ownership.19

We conducted a longitudinal case study, in a large US nursing home chain that is currently private equity-owned. We studied the strategies that were executed both before and after the acquisition. Furthermore, we examined financial performance, as well as quality performance measures over time. The central research question was “What happens to a nursing home chain when private equity takes over?” Our study adds to previous studies on the topic, by focusing on “how” private equity is at work in an industry that is taking care of frail elderly.

Methods

Case Selection

This foundational study used a longitudinal case study (2000-2012) of a private equity-owned US nursing home chain, named Golden Living. The company was named Beverly Enterprises until the LBO by Fillmore Capital in 2006. Golden Living owned more than 300 nursing facilities in 21 states (source: http://www.goldenlivingcenters.com/home.aspx [retrieved March 11, 2015]) and additionally delivered assisted living, rehabilitation therapy, hospice services, group purchasing to health care companies, and health care staffing. The company, originally founded in 1963, employed about 42 000 employees in 2012. The case study methodology allowed for an in-depth, focused analysis of the nursing home chain and was ideal for examining a contemporary set of events, over which we had little or no control.20 LBOs are complex phenomena where context is important. Little is known about strategies and results after LBOs in nursing homes, and a case study approach is well suited as an exploratory and exemplifying analysis. We believe this is one of the first in-depth case studies on the private equity phenomenon in general, and the very first in the nursing home sector in particular.

The case was purposively selected for 3 reasons. First, Golden Living, a publicly traded company on the New York Stock Exchange since 1982, was purchased by private equity firm Fillmore Capital in March 2006 for about $2.3 billion. The period of private equity ownership was considered as long enough to study developments over time. Moreover, Golden Living was one of the largest LBOs in that period. The effects and strategies are therefore relatively well documented, and it makes the case very relevant from a welfare point of view. Second, Golden Living was acquired by a midsized private equity firm. The majority of private equity deals in health services is carried out by midsized private equity firms.21 Third, strategic changes in a company can be initiated by any new owner or leader of a company, whether it is a private equity owner or not.22 In 2000, a new President and CEO was appointed and the ownership transfer to Fillmore Capital was also accompanied by a new CEO in 2006. Because we have gathered data for the period 2000-2012, we were able to compare the leadership change without private equity backing to the leadership change that was initiated by the new private equity owner.

It is important to note that Golden Living was already a large, New York Stock Exchange–listed public for-profit chain. The company converted from being publically listed and under Securities and Exchange Commission regulations, to private equity ownership. This private ownership comes with far less regulatory scrutiny and compliance cost. While public companies are highly subject to short-term profit demands by market investors, private equity-owned companies have more latitude for longer-range strategic planning. The results of the case have to be interpreted against this background.

Data Sources

We triangulated qualitative and quantitative data sources as part of a deliberate search for confirming and disconfirming evidence. Our mixed-methods design had a longitudinal and comparative approach for both quantitative and qualitative data. We analyzed changes over time and contrasted strategies and outcomes in our case with industry developments.

First, we analyzed qualitative data over the period 2000-2012, as available in press releases, Provider Magazine, and reports of litigation actions. The annual top-50 information on nursing home chains in Provider Magazine, including an analysis of the main developments and strategies in the industry of each particular year, served as the main background to compare the strategies of Golden Living to those of other US nursing home chains. We did a structured search in LexisNexis on the search terms “Golden Living” (965 hits, selection of 88 articles) and “Beverly Enterprise” (996 hits, selection of 134 articles) (a complete list of the documents studied is available from the authors). In addition, we interviewed purposively selected respondents: a central Golden Living executive, 2 representatives from private equity firm Fillmore Capital, the CEO of Golden Living, and an attorney involved in a class action lawsuit against several facilities of Golden Living. These qualitative data provided insights in the company’s strategies.

Second, we compiled a data set for Californian nursing homes (covering about 1200 facilities for each year), using cost report data of the California’s Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) for the period 2000-2012. We compared relevant outcomes for Golden Living facilities with regard to financial performance and resident well-being for the pre- and postpurchase period, and weighted the results for Golden Living against industry counterparts. For the analysis, we excluded nonprofit, government, and hospital-based facilities from the comparison group, because they have very different financial patterns. One limitation of the study was that we did not have access to company financial data after 2006 and California nursing home cost data may not have been representative of the company’s overall financial picture. Although there were no indications that the Californian Golden Living facilities differ strongly from the company’s facilities in other states, utmost care must be exercised while generalizing the data to the whole company. We added quantitative staffing data and deficiencies (violations of quality regulations) for all Golden Living facilities in the US compared with other US nursing homes from the Online Survey, Certification and Reporting (OSCAR) data (covering about 14 700 facilities).

Concepts and Definitions

Our case study focused on the concepts corporate strategy, financial performance, and resident well-being.

Corporate strategy

Strategy was a central concept in this study, because we focused on “how” private equity is at work. Corporate strategy is about organization-wide changes, as initiated by top management. Strategy was approached as a combination of deliberately “planned” change and emergent events “imposed” by environmental forces.23 Qualitative data were the main data source for reconstructing strategy over 2000-2012. In addition, from the data sets, we regarded payer mix as an indicator of strategy, because nursing homes that focus on maximizing financial performance may shift resident census from Medicaid in favor of financially higher paying Medicare and private payers.13,24 Furthermore, we also regarded staffing, as well as skill mix, as part of a deliberate strategy, because these variables give information about the management of labor costs. Staffing is also closely related to quality outcomes and often regarded as a structural measure of resident care quality.17,25

Financial performance

Financial performance included 4 variables. First, we included operating and total margins, which have been regarded as traditional measures of financial performance in health care literature.13,26 In addition, we included data on the long-term debt/asset ratio (because private equity firms may use relatively much debt in their portfolio companies) and net income per patient day.1,2

Resident well-being

From the national OSCAR data set we included data on about 300 Golden Living facilities and total US nursing homes on total deficiencies, and serious deficiencies. Deficiencies are often used in academic studies as a measure of care quality.17,25 Nursing homes participating in Medicare and Medicaid are required by federal law to disclose all deficiencies. At last, data on litigation actions against the company reported in the news were identified. A definition of each variable included is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Concepts, Variables, Definitions, and Data Sources.

| Variables | Definition | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| Corporate strategy | ||

| General strategy | Organization-wide changes, as initiated by top management | Press releases, Provider Magazine, interviews |

| Payer mix | The percentage of revenue from Medicare, Medicaid (called Medi-Cal in California), and other payers (ie, the sum of revenues from self-pay patients, managed care patients and other payers). | California’s OSHPD for the period 2000-2012 |

| Staffing hours ppd | Average number of staffing hours ppd, of direct care professionals: RNs, LVNs, and NAs. | OSHPD data 2000-2012 and OSCAR data for 2003-2012 |

| Skill mix | RN productive hours/(LVN productive hours + NA productive hours). The composition of nursing staff by licensure/educational status. | OSHPD data 2000-2012 |

| Financial performance | ||

| Operating margin percentage | Net from Health Operations / Total Health Care Revenue. Focuses on core business functions and excludes the influence of nonoperating incomes and expenses. | OSHPD data 2000-2012 |

| Total margin percentage | (Total revenue – total expenses) / total revenue. Includes all operating and nonoperating revenues and expenses. | Idem |

| Net income per patient day (ppd) | Net income of the company / total number of patient days. | |

| Long-term debt / asset ratio | Long-term debt / total assets. Percentage of assets that are financed with loans and financial obligations lasting more than one year. General measure of the financial position of a company. | |

| Resident well-being | ||

| Total deficiencies | Deficiencies are issued to facilities that fail to meet the federal standards for Medicare and Medicaid participation. Deficiencies are classified into several categories on the basis of their scope and severity. | OSCAR data 2003-2012 |

| Serious deficiencies | So-called level G or higher deficiencies, including those deficiencies that that cause harm or jeopardy to residents. | |

| Litigation actions | Major lawsuits by the state or federal government or private parties reported in the media. | Press releases and reports of litigation actions |

Note. OSHPD = Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development; ppd = per patient day; RNs = registered nurses; LVN = Licensed Vocational Nurse; NAs = Nurse Assistants; OSCAR = Online Survey, Certification and Reporting.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data from press releases as well as the interviews were categorized chronologically and then thematically content analyzed using software for qualitative data analysis (MaxQDA). We inductively added and specified codes while analyzing our data. We stopped adding new codes at the point of theoretical saturation. The qualitative data from the interviews supported and specified the findings on strategy.

Quantitative data were analyzed using Mann–Whitney U tests to compare the scores of Golden Living facilities with other Californian for-profit facilities, using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Furthermore, we conducted Wilcoxon signed rank tests for each variable, to compare prepurchase period (2000-2005) and postpurchase period (2006-2012) scores. We only reported outcomes of the pre-post analyses if we found remarkable contrasts in comparison with industry trends. At last, the OSCAR data on staffing and deficiencies were analyzed using Satterthwaite t tests for unequal variances.

Results

Corporate Strategy

Mr. Floyd was appointed as the new CEO of Beverly Enterprises Inc in 2001. As the largest for-profit chain in the US, Beverly faced serious financial problems at that time, like many other nursing home chains. In spite of efforts to turn around the company, Beverly faced a large number of lawsuits alleging neglect of residents and deaths in states like Arkansas, California, and Florida. The company was subject to a US Health and Human Services Department and US Department of Justice Corporate Integrity (oversight) Agreement from a 2000 settlement agreement for poor quality of care. As a result of these problems, Beverly company stock fell dramatically to less than $2 per share.

As the company’s financial status and its stock prices improved in the following years, it became the target of a “hostile and secret acquisition of shares” by private investment firm Formation Capital. In 2005, Beverly’s board of directors therefore announced an auction process “to maximize value for all of the company’s stockholders as soon as practicable through a sale of the company.” In March 2006, private equity firm Fillmore Capital acquired Beverly Enterprises Inc, which was then renamed Golden Living. The ownership change was accompanied by a newly appointed 3-member board of directors, with Fillmore President Mr Silva as the new chairman. Mr Churchey was named CEO and was replaced by Mr Kurtz in 2008. For the pre- and postpurchase period, many strategies were continued and reinforced, while the private equity owners also applied some new strategies (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the Main Strategies Executed.

| Continuing strategies (both pre- and postpurchase) | Postpurchase strategies |

|---|---|

| • Divestmenta • Diversificationa • Intensified corporate control • Staffing level controla |

• Restructuringa • Rebranding • Relocation • Accelerated ICT investments • Increased skill mix and employee training and benefits |

Note. ICT = information and communication technology.

An industry-wide trend: Strategy executed by many other for-profit nursing homes chains as well.

Divestment and diversification

From 2001 onward, Golden Living divested more than 150 nursing home facilities, mainly motivated by high patient liability costs in states like Arkansas and Florida. When the company started its divesture program, CEO Floyd explained that

this first group of [20] facilities . . . were expected to generate . . . less than six percent of our total revenues, but they accounted for 20 percent of our total patient care liability costs projected for this year. . . . Except for disproportionately high liability costs, these would be very successful facilities.

Although some single nursing homes were closed down, most of the nursing homes were sold to other nursing home chains, real estate companies, or investment companies. The company mainly divested nursing home facilities, but there were other divestments as well, such as the divestment of 141 outpatient therapy rehabilitation clinics and of 20 licensed home care agencies. Divesture was an industry-wide trend at that time: slashed Medicare rates and high leverage forced many nursing home chains to shed unprofitable facilities. The divestment of unprofitable nursing homes continued in the postpurchase period. By 2006, Beverly was the second largest US for-profit chain with 342 facilities and 35 839 beds.27 After more divestment, Golden Living was ranked fourth in size with 302 facilities and 30 790 beds in December 2012.28

Mainly after 2004, the strategy of divestment was accompanied by diversification efforts. The company started to invest in new profitable services, such as rehabilitative services, Alzheimer’s units, and hospice care. This diversification strategy was implemented to attract more private-pay and Medicare postacute care revenue. CEO Floyd described the strategy as building Beverly “into a diversified eldercare services company, with ancillary businesses in the high-growth, high-margin areas of healthcare services.” Again, diversification strategies were an industry-wide trend at that time. This strategy continued postpurchase, with a focus on the growth of home health and hospice business. Furthermore, new company development was added. Postpurchase CEO Kurtz explained:

We’ve created companies ourselves, diversifying the revenue stream. We created a rehab company, we created a hospice company, a pharmacy company, a staffing company. We’ll start a company that will provide transitional care management. So we create companies to create value.

Golden Living’s nursing homes often served as the essential business for the development of its newly created companies. For example, in 2012, Fillmore Capital launched pharmacy services company AlixaRx, for which Golden Living served as the necessary “launch customer”: AlixaRx started off with an agreement with Golden Living to provide pharmacy services to the company’s more than 300 centers. Fillmore Capital’s chairman of the board of directors Silva stated that “AlixaRx will be wildly profitable.”

In spite of this diversification strategy to attract more Medicare and private-pay patients, our analysis of the California OSHPD data showed the opposite: Golden Living served significantly more Medicaid patients from 2007 onward. At the same time, from the private equity ownership in 2006 onward, the percentage of revenue from private payers was significantly lower than this revenue stream in other for-profit companies in California (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Median Scores for Golden Living Facilities for 2000-2012; Compared With Other For-Profit Facilities in California.

| Variables\year | Prepurchase |

Postpurchase |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |

| Strategy | |||||||||||||

| Staffing hours ppd (California) | |||||||||||||

| • RN | .33 | .31 | .31 | .33 | .39 | .30 | .22 | .22 | .28 | .35 | .45* | .59** | .68** |

| • LVN | .62 | .63 | .61 | .61 | .56 | .63 | .61* | .71 | .73 | .72* | .62** | .50** | .40** |

| • CNA | 2.15 | 2.21 | 2.26 | 2.33 | 2.39 | 2.38 | 2.57** | 2.29* | 2.29* | 2.23** | 2.24* | 2.28* | 2.31* |

| • Total staffing (RN + LVN + NA) | 3.10* | 3.14 | 3.24 | 3.29 | 3.31 | 3.31 | 3.40 | 3.24** | 3.29* | 3.28** | 3.31** | 3.35** | 3.44* |

| Staffing hours ppd (US)a | |||||||||||||

| • RN | .50** | .51** | .50** | .50** | .50** | .55** | .62** | .68 | .76* | .76 | |||

| • Total staffing (RN + LVN + CNA) | 3.06** | 3.11** | 3.11** | 3.12** | 3.16** | 3.29** | 3.35** | 3.40** | 3.44** | 3.44** | |||

| Skill mix | .11 | .11 | .10 | .11 | .13 | .10 | .07 | .09 | .09 | .12* | .16* | .21** | .26** |

| Payer mix | |||||||||||||

| • Medicare | 11.70* | 10.72* | 10.11* | 12.23 | 9.53 | 10.90 | 23.05** | 12.19 | 13.13 | 12.36 | 12.19 | 11.81 | 11.57 |

| • Medi-Cal (Medicaid) | 64.97 | 69.88 | 69.10 | 37.67 | 79.12 | 80.08 | 66.24 | 79.53* | 79.03* | 76.90* | 79.27* | 79.35* | 79.86** |

| • Other payers | 23.90 | 20.91 | 17.47 | 17.58 | 9.58 | 6.94 | 8.28* | 8.90* | 7.84* | 7.24* | 7.82* | 8.30* | 6.92* |

| Financial performance | |||||||||||||

| Operating margin | 5.56 | 9.87* | 3.32 | –3.81* | –5.99* | 1.33 | 12.54** | 10.47** | 9.13* | 12.47** | 11.34** | 15.00** | 8.99* |

| Total margin | −.77 | –.82 | –.91* | –.96** | –.87 | −.81 | −.62** | −.83 | −.74 | −.72 | −.64* | −.71 | −.60* |

| Net income per patient day | 5.18 | 9.69 | 3.19 | –8.76* | –5.82 | 1.49 | 25.35** | 22.93** | 20.82* | 29.84** | 18.23* | 24.76* | 13.61 |

| Long-term debt/asset ratio | .78* | .00 | .00 | .00 | –66.67* | –84.02* | .00* | 64.91** | 68.77** | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Resident well-being | |||||||||||||

| Total deficiencies (US)a | - | - | - | 6.79** | 6.29** | 5.67** | 7.47** | 8.43 | 7.27** | 7.95 | 7.29 | 7.67 | 7.19 |

| Harm deficiencies (US)a | - | - | - | .34** | .33** | .37** | .52 | .63 | .41* | .39 | .43 | .44 | .27** |

Note. Italic: Lower score than industry counterparts; all other scores are higher than those of industry counterparts. ppd = per patient day; RN = registered nurse; LVN = Licensed Vocational Nurse; CNA = Certified Nurse Assistant; NA = Nurse Assistant; OSCAR = Online Survey, Certification and Reporting; OSHPD = Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. The scores for industry counterparts are available from the authors.

The mean US scores on staffing and deficiencies were derived from the OSCAR data set; the other scores were derived from the California OSHPD data.

P < .05. **P < .001.

Intensified corporate control

Both before and after the acquisition, the respective boards executed a strategy of intensified corporate control. We found 3 manifestations of intensified control prepurchase. First, a new labor management system was introduced to facilitate greater control over the use of staff and to reduce the use of temporary labor. Second, performance-related pay was introduced for managers. Each individual facility was judged by a scorecard, with factors such as pretax income, employee turnover, occupancy, bad debt and quality of care. Third, local managers were given a smaller span of control, being responsible for approximately 10 homes each, about half the number they had been overseeing.

The private equity owners reinforced this strategy, by further reducing the span of control of local directors; they now managed 6 to 8 nursing home facilities instead of 10. Postpurchase, the focus on performance-related pay was also enhanced. CEO Kurtz explained:

As part of the decentralization, we very dramatically increased the compensation for the leaders of our LivingCenters. . . . [Their] performance, both financial performance and clinical excellence, defines how their pay would be allocated. . . . They can almost double their salary. We tried to switch more of the salary to compensation based on performance rather than just base salary.

Control staffing levels

A strategy that emerged from the analysis of the data sets is the control of staffing levels, both pre- and postpurchase (see Table 3). We found that the total staffing hours per patient day (ppd) in California, while being highly comparable to industry counterparts prepurchase, became significantly lower from 2007 onward. This trend also held for Certified Nurse Assistant (CNA) staffing hours ppd, and from 2009 onward also for Licensed Vocational Nurse (LVN) staffing hours ppd, which were significantly lower for many years postpurchase. In contrast, from 2010 to 2012, Golden Living had significantly higher RN staffing levels than its industry counterparts in California. The company stressed in its company information and in interviews that it deliberately increased the number of RN caregivers. The skill mix (the proportion of higher educated nurses when compared to lower educated nurses) was indeed significantly higher from 2009 onward. While total staffing levels in California were lower during private equity ownership, the composition of staffing changed in favor of higher educated nurses. The national data on staffing show a roughly similar pattern. However, here we see that the total staffing as well as the RN staffing were also significantly lower prepurchase, for the years 2003-2005. National data also showed a rise in RN staffing on the national level for 2010-2012, with significantly higher RN staffing for the year 2011. Golden Living’s RN and total staffing levels increased after 2008 consistent with the substantial staffing increase in US facilities, but its total staffing levels did not keep pace with the national trends.

Restructuring, rebranding, and relocation

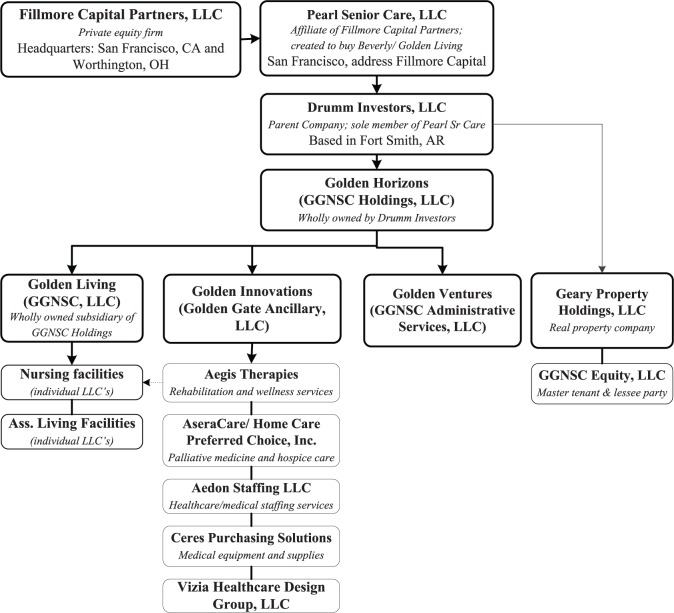

Several postpurchase strategies mark a change when compared with the prepurchase period. A first change in this respect is the legal restructuring of the company, by adding new layers and Limited Liability Companies (LLCs). With regard to the layering, Fillmore Capital created Pearl Senior Care LLC to purchase Golden Living. Pearl Senior Care in turn owned Drumm Investors, LLC, which in turn owned Golden Horizons (the operation company) and Geary Property Holdings (the real estate). The operations were thus legally separated from the buildings and the land of the nursing home facilities (see the chart in the appendix). Nursing home facilities in turn leased their buildings and land. Furthermore, Golden Living’s nursing homes were split up into separate LLCs. The extra layers and LLCs often hinder state and federal oversight of quality of care and make it more difficult for the government to hold the company accountable.29 The private equity owner stated that risk reduction for the lenders was the main argument:

Our lenders required, as part of the financing, each property and each operating company to be set up in LLC’s. It’s safer for them. If one goes bankrupt. . . . And there may be marginal litigation benefit.

However, the legal structuring was not a unique private equity strategy: By 2008, the top 10 US nursing home companies had converted most of their individual nursing facilities into LLCs, with separate management and property companies and complex multilevel ownership structures.9,29

A second change that marked the new company ownership was its rebranding. While the company was named Beverly Enterprises Inc at the moment of the takeover, its name changed to Golden Gate National Senior Care (GGNSC) at the time of the acquisition. A deliberate rebranding effort followed, including internal and external research among consumers and employees, resulting in the “Golden family” of company names. The nursing centers were named Golden Living. The new company name was supported by new logos and graphics. Private equity owner Mr Silva stated that

[the new name] sets the stage for what the company is going to represent in the future. We want it to become the leading brand in long-term care.

A third postpurchase change was the relocation of the company headquarters (where about 600 people worked) from Fort Smith (Arkansas) to Plano (Texas) in 2011. The Golden Living Administrative Center, providing administrative services to all of the company’s businesses, remained located in Arkansas. An important reason given for the move was the high litigation costs in Arkansas. The Golden Living CEO indicated:

It costs $ 17,000 per bed a year to defend against liability claims in Arkansas, versus a national average of $ 2,000 a bed per year. . . . It’s perverse to me that one of the leading long-term care companies is based in a state where they don’t have tort reform for nursing homes.

However, the company also stated that other factors pushed the move in 2011, such as travel expenses (consolidating near a “large hub airport’ would save money), and a welcoming business environment (the State of Texas invested $2.1 million in Golden Living’s headquarters relocation).

Focus on information and communication technology and employee training and benefits

After the acquisition in 2006, our data point at an increased focus on both information and communication technology (ICT) and employee training and benefits. Although Golden Living reported ICT investments prepurchase, the number of ICT implementations accelerated postpurchase. New applications aimed at enhanced access to real-time electronic health record charting, resident assessment and care planning, labor oversight, and cost reductions. CEO Kurtz stated that Golden Living “became much more sophisticated in the use of technology.” He explained,

We invested heavily in mobile technology. It’s all part of our strategy to try to become very efficient in giving information to our staff. Most of that information is about training, although we’re also using mobile technology to help in the billing process, so it’s more efficient how we bill. It also allows us to be more efficient in how we retrieve information.

In addition, qualitative data point at the investment in employee training and benefits. The company stated that it accelerated some employee compensations payments, and benefits, such as employer-paid life insurance, improved health care coverage, and discounts on auto and home insurances, as part of the merger agreement. Golden Living also reported several investments in training. For example, it hired approximately 200 RNs as Directors of Clinical Education, who were responsible for clinical training for health care staff. Furthermore, the company stated that new CNAs were offered a 33-day course before they started working at Golden Living facilities. CEO Kurtz stated that

the company invested heavily in training. We think that is one of the most important things we can do, to maintain quality. . . . We are pretty focused on making sure that our people are very fluent in policies and procedures. We’re testing to make sure that they are fluent with their policies and procedures.

Financial Performance and Resident Well-Being

In addition to the strategies executed both pre- and postpurchase, we analyzed company scores on measures of financial performance and resident well-being (see Table 3).

Financial performance

Although Golden Living’s operating margins in California were relatively low in the 3 years preceding the takeover, the company structurally outperformed its industry counterparts postpurchase, showing higher operating margins. We also found higher net incomes per patient day in the postpurchase years, with significantly higher incomes for the years 2006 to 2011. We did not find the same results for total margins, which also includes nonoperating revenues and expenses.

The long-term debt to assets ratios of Golden Living’s California facilities (the total liabilities divided by total assets) were rising considerably in comparison with industry counterparts directly after the takeover, but the long-term debt ratios approached industry averages after those years. The long-term debt ratios were significantly higher for the postpurchase period for Golden Living facilities (Z = –2.46, P = .014). In contrast, other for-profit facilities in California showed significantly lower long-term debt ratios (Z = –7.34, P < .001) for the postpurchase period. Golden Livings’ long-term debt ratios thus increased in association with the change in ownership.

Resident well-being

Golden Living scored significantly lower on the total number of deficiencies and on serious deficiencies nationwide prepurchase. This lower number of deficiencies might be related to the earlier mentioned divesture program, in which the company potentially divested relatively deficient nursing homes. Postpurchase, mean scores were comparable to the national average for nursing facilities for most years, showing a shift to industry averages. This indicated that the private equity-owned company did not improve quality of care.

Our qualitative data show that sizable litigation actions occurred in both the pre- and the postpurchase period. As noted above, Beverly was placed under a Corporate Integrity Agreement with federal oversight for its failure to comply with quality and regulatory requirements in 2000 which was removed in 2006 when the company was sold. In 2002, the company settled a case for elderly abuse with the California Attorney General, paid more than $2 million in penalties and fines and promised to improve the quality in all its facilities. It also settled a case with the Arkansas Attorney General for mistreatment and neglect of residents in 12 nursing homes in 2005. After purchase, Golden Living settled a $20 million suit with the US Department of Justice (USDOJ) and the California Attorney General for false reimbursement for medical equipment by a subsidiary company in 2006. In 2011, a class action case for inadequate staffing levels in California Golden Living facilities was filed and later settled. Pennsylvania’s attorney general also filed an action against Golden Living for inadequate staffing levels and fraudulent billing in 2012. The USDOJ intervened in an Alabama whistleblower suit against Golden Living’s AseraCare hospice company in 2012. Finally, the USDOJ reached a 2013 settlement with Golden Living for providing inadequate wound care in Georgia (filed in 2010) that required a Corporate Integrity Agreement for federal oversight. However, the four other largest US chains also had a number of litigation actions.11 Golden Living had litigation actions similar to other large US nursing home chains. Litigation actions, because of poor quality, continued to occur after the private equity purchase, which indicates that the private equity-owned company was not able to improve care quality, ie, resident well-being.

Conclusion

Research on the impact of private equity in health services shows mixed findings, as outcomes vary with private equity owner’s strategies and the company context. We therefore shifted the focus from “what” the impact of private equity is to “how” private equity can have an impact in health services organizations. Our longitudinal, in-depth case study of the nursing home chain Golden Living generally shows how the private equity owner mainly continued and reinforced strategies that were already in place prepurchase. Examples of ongoing strategies are the intensification of corporate control, diversification of services, and divestment of nursing home facilities. Under private equity ownership, Golden Living further pursued a strategy of low staffing levels in comparison to the national average in both the pre- and the postpurchase periods. Its gradual increase in staffing over time did not keep pace with the national growth in staffing in most years. It should be noted that Golden Living and most other for-profit nursing homes, in contrast to nonprofit and government nursing homes, do not meet the minimum staffing levels for providing safe care recommended by experts and by the government.30,31 At the same time, the private equity owner invested in the composition of staffing, in favor of the higher educated nurses (RNs), which is in contrast to former research on skill mix.16Golden Living chose a strategy of “brains” (fewer high-paid high-educated nurses) over “hands” (many low-paid low-educated nurses).

The private equity owner also developed some new strategies in the postpurchase period, such as the rebranding of the company, increased investment in employee benefits and training, the relocation of the company’s headquarters, the establishment of nursing home facilities as LLCs, rising debt ratios directly after the takeover, and the separation of the nursing home operating companies from the property company.

Many of the strategies executed under private equity ownership mimic industry-wide trends, as the strategies of strict staffing controls, divestment, diversification, and the restructuring of the company in LLCs were consistent with developments in other for-profit chains.9,15,17,29,32Moreover, scores on care quality indicators remained relatively low, as well as total staffing levels. We conclude therefore that the private equity-owned company under study mainly conformed to other large for-profit nursing home chains. This is in line with theory about institutional isomorphism33 that stresses the similarities between organizations as a result of imitation or independent development under similar constraints. The case study thus revealed how private equity owners merely reinforced the profit-seeking strategies that were already in place prepurchase and added some strategies to further support efficiency, such as accelerated ICT investments.

Furthermore, apart from operational strategies or financial engineering strategies (the extraction of wealth without necessarily adding value),34 our case study revealed how the private equity owner created financial value beyond the company itself by executing a novel strategy. The private equity owners used Golden Living as a “launch customer” for putting new companies on the market, which had guaranteed income by contracting with the Golden Living nursing home facilities. This could explain why the private equity firm holds onto the nursing home chain relatively long, as most LBOs last only 3 to 7 years. Like other nursing home chains, the company used its related-party contracts to extract profits from the nursing facilities.35 This finding uncovers a limitation of research on private equity, because it is mainly restricted to what happens within one portfolio organization.

The presented case study shows the need to study private equity buyouts in health services from a broad perspective, because this can shed new light on what happens when private equity takes over.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof Dr Paul Boselie and Prof Dr Margo Trappenburg for reviewing earlier versions of the article and for their helpful suggestions to improve it.

Appendix

The legal restructuring results in the following simplified chart.

Main source. Ernst & Young, Report of Independent Auditors GGNC Holdings LLC. Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements Periods Ended December 31, 2007 and 2006. 2008. USA.

Note. The chart does not take into account the nursing homes that retain the name Beverly Healthcare, which is the case for around 80 homes. GGNSC = Golden Gate National Senior Care.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors received financial support for the resarch from the Dutch Prince Bernard Culture Fund.

References

- 1. Palepu KG. Consequences of leveraged buyouts. J Financ Econ. 1990;27(1):247-262. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gilligan J, Wright M. Private Equity Demystified: An Explanatory Guide. London, England: Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, Centre for Business Performance; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Government Accountability Office. Nursing Homes: Complexity of Private Investment Purchases Demonstrates Need for CMS to Improve the Usability and Completeness of Ownership Data. Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burns D, Cowie L, Earle J, et al. Where Does the Money Go? Financialised Chains and the Crisis in Residential Care. Manchester, England: Centre for Research on Socio-Cultural Change; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Froud J, Williams K. Private equity and the culture of value extraction. New Polit Econ. 2007;12(3):405-420. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duhigg C. At many homes, more profit and less nursing. The New York Times. September 23, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Robbins CJ, Rudsenske T, Vaughan JS. Private equity investment in health care services. Health Affairs. 2008;27(5):1389-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bain and Company. Global Healthcare Private Equity Report 2015. Boston, MA: Bain and Company; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cuff K, Hurley J, Mestelman S, Muller A, Nuscheler R. Public and private health-care financing with alternate public rationing rules. Health Econ. 2012;21(2):83-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harrington C, Hauser C, Olney B, Rosenau PV. Ownership, financing, and management strategies of the ten largest for-profit nursing home chains in the United States. Int J Health Serv. 2011;41(4):725-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harrington C, Jacobsen FF, Panos J, Pollock A, Sutaria S, Szebehely M. Marketization in long-term care: a cross-country comparison of large for-profit nursing home chains. Health Serv Insights. 2017;10:1-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pradhan R, Weech-Maldonado R, Harman JS, Laberge A, Hyer K. Private equity ownership and nursing home financial performance. Health Care Manage Rev. 2013;38(3):224-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cadigan RO, Stevenson DG, Caudry DJ, Grabowski DC. Private investment purchase and nursing home financial health. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(1):180-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Stevenson DG, Grabowski DC. Private equity investment and nursing home care: is it a big deal? Health Affairs. 2008;27(5):1399-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pradhan R, Weech-Maldonado R, Harman JS, Al-Amin M, Hyer K. Private equity ownership of nursing homes: implications for quality. J Health Care Financ. 2014;42(2):1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Harrington C, Olney B, Carrillo H, Kang T. Nurse staffing and deficiencies in the largest for-profit nursing home chains and chains owned by private equity companies. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1):106-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grabowski DC, Hirth RA, Intrator O, et al. Low-quality nursing homes were more likely than other nursing homes to be bought or sold by chains in 1993–2010. Health Aff. 2016;35(5):907-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rodrigues SB, Child J. Private equity, the minimalist organization and the quality of employment relations. Hum Relat. 2010;63(9):1321-1342. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wright M, Bacon N, Amess K. The impact of private equity and buyouts on employment, remuneration and other HRM practices. J Ind Relat. 2009;51(4):510-511. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yin RK. Applied Social Research Methods Series, Vol. 5—Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Robbins CJ, Rudsenske T, Vaughan JS. Private equity investment in health care services. Health Affair. 2008;27(5):1389-1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang Y, Rajagopalan N. Once an outsider, always an outsider? CEO origin, strategic change, and firm performance. Strat Manag J. 2010;31(3):334-346. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mintzberg H, Waters JA. Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strat Manag J. 1985;6(3):257-272. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Konetzka RT, Norton EC, Stearns SC. Medicare payment changes and nursing home quality: effects on long stay residents. Int J Health Care Finance Econ. 2006;6(3):173-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hillmer MP, Wodchis WP, Gill SS, Anderson GM, Rochon PA. Nursing home profit status and quality of care: Is there any evidence of an association? Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(2):139-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weech-Maldonado R, Neff G, Mor V. Does quality of care lead to better financial performance? the case of the nursing home industry. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28(3):201-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Top 50 largest nursing facilities companies. Provider Magazine. June, 2006:36-43. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Top 50 largest nursing facilities companies. Provider Magazine. June, 2013:43-47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stevenson D, Bramson JS, Grabowski DC. Nursing home ownership trends and their impacts on quality of care: a study using detailed ownership data from Texas. J Aging Soc Policy. 2013;25(1):30-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes (Report to Congress: Phase II Final. Volumes I to III). Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harrington C, Schnelle JF, McGregor M, Simmons SF. The need for higher minimum staffing standards in U.S. nursing homes. Health Serv Insights. 2016;9:13-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kitchener M, O’meara J, Brody A, Lee HY, Harrington C. Shareholder value and the performance of a large nursing home chain. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(3):1062-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. DiMaggio PJ, Powell PW. The iron cage revisited: institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am Socio Rev. 1983;48:147-160. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Appelbaum E, Batt P. Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street: When Wall Street Manages Main Street. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Harrington C, Ross L, Kang T. Hidden owners, hidden profits, and poor nursing home care: a case study. Int J Health Serv. 2015;45(4):779-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]