Abstract

Understanding attitudes toward suicide, especially among healthcare personnel, is an important step in both suicide prevention and treatment. We document the adaptation process and establish the validity and reliability of the Attitudes Toward Suicide (ATTS) questionnaire among 262 healthcare personnel in 2 major public hospitals in the Klang Valley, Malaysia. The findings indicate that healthcare personnel in Malaysia have unique constructs on suicide attitude, compared with the original study on a Western European sample. The adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire demonstrates adequate reliability and validity for use among healthcare personnel in Malaysia.

Keywords: suicide, attitude, validation, health care, Malaysia

Introduction

Globally, an estimated 804 000 individuals died by suicide in a year,1 of which 60% occurred in Asia.2 Suicide is a rising problem in Malaysia, with a 60% rise in suicide cases during the last 45 years.3 Suicide is also a significant issue among adolescents, with 12.6% reporting severe suicide ideation.4 The suicide rate in Malaysia is estimated to be between 1.185 and 86 per 100 000 population. However, the concern is that these reported rates may be higher due to underreporting and misclassification as undetermined deaths.7,8

In a health care context, approximately half of the individuals who suicided contacted the hospital emergency department at least once within the year of their death,9 or received health service care within 4 weeks of their death, of which 20% were considered preventable.10 The number of hospital admissions for suicide attempts in Malaysia is increasing.11 Meanwhile, one-fifth of suicide deaths occurred in Malaysian hospitals.4 However, a systematic review revealed that general hospital personnel, in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Australia, held negative attitudes toward suicidal patients.12 Meanwhile, other studies, including a worldwide systematic review from the patients’ perspective, indicated a perception that healthcare personnel were nonempathetic and exhibited stigmatizing behavior.13,14 This could hinder help-seeking behavior among at-risk suicidal individuals.15 Considering the importance of suicide prevention and management in a health care setting,16,17 and because suicide attitude is influenced by culture,18,19 it is crucial to adapt and validate a Malaysian suicide attitude questionnaire.

A literature search was conducted to determine the most suitable questionnaire for cross-cultural adaptation and validation in Malaysia (see the “Methods” section for the description of the Attitudes Toward Suicide [ATTS] questionnaire). This study adopted the ATTS questionnaire, as it was considered a valid and feasible instrument during a systematic review by Kodaka et al,20 was built on existing questionnaires,21-23 and informed by expert knowledge in this field.24 Furthermore, it was employed in the health care setting25-28 and the Asian context.29-34

The aim of this study was to translate, adapt, and assess the validity and reliability of the ATTS questionnaire for use among healthcare personnel in a Malaysian context.

Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study of healthcare personnel, from 2 major public hospitals in Malaysia, to establish the validity and reliability of the Malay ATTS.

Phase I: Translation and Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process

The ATTS questionnaire was developed by Salander Renberg and Jacobsson,24 who aimed to build a feasible instrument that enabled a large-scale measurement of attitudes toward suicide. The second version of the ATTS questionnaire is composed of 37 items, scored on a 5-point Likert scale incorporating “Strongly Disagree,” “Disagree,” “Undecided,” “Agree,” and “Strongly Agree.” The responses were coded as “Strongly Disagree” = 1 to “Strongly Agree” = 5, except for items 4 and 6, which were reverse coded. An exploratory factor analysis revealed 10 interpretable factors as Suicide as a right; Incomprehensibility; Noncommunication; Preventability; Tabooing; Normal/common; Suicidal process; Relation-caused; Preparedness to prevent; and Resignation. Higher scores indicated agreement with the factor or domain. The α coefficients ranged from 0.38 to 0.86.

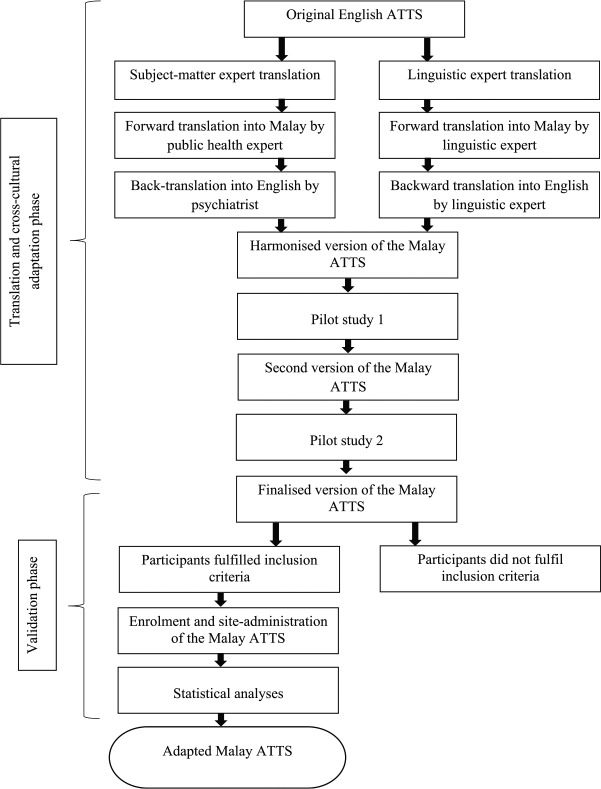

The English ATTS questionnaire was forward- and backward-translated from English to Malay independently by subject-matter and linguistic experts. The subject-matter experts were a public health specialist (forward translation) and a psychiatrist (backward translation). To ensure content validity, a harmonization meeting was held to combine the 2 versions of the translated questionnaire, comprising of a multidisciplinary team of psychiatric, psychological, behavioral science, public health, and linguistic experts. The adaptation process took into account factors of barriers in linguistics comprehension, contextualized meaning attached to a construct, and possible interpretations of the translated instrument.35

Two pilot studies were conducted on the translated instrument. Through a convenience sampling from 2 public hospitals, the authors recruited 51 and 49 healthcare personnel for each pilot study, respectively. After reviewing the results of the first pilot study, improvements were made to items with low corrected item-total correlation, which contributed to the low total Cronbach’s α. A second pilot study was implemented to test the improved questionnaire, and, compared with the first version of the translated questionnaire, yielded a higher total Cronbach’s α of 0.53. The Malay ATTS questionnaire was finalized for further validation with a larger sample.

Phase II: Validation Process

Participants

To validate a questionnaire, between 2 and 20 participants per item are needed,36,37 with a minimum of 250 participants.38 In this study, assuming that 8 participants are needed per item, with a drop-out rate of 10%, 325 participants were targeted for recruitment.

For inclusion criteria, the following core medical and surgical departments were selected: general medical, general surgery, accident and emergency, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, orthopedics, and psychiatry. Doctors, nurses, assistant medical officers, and medical attendant professions were included. All participants were Malaysians, but trainees were excluded from the study.

Procedures

Participants were randomly sampled based on the sampling frame with the names of all staff from the related professions and departments. Participation was voluntary, and strict confidentiality was maintained with no identifier being used in the questionnaires. After giving informed consent, participants filled out the questionnaire, consisting of the Malay ATTS and demographic information, such as age, gender, race, religion, marital status, occupation, education, department, years of service, number of suicidal patients cared for, and training in the management of suicidal patients. The participants returned the questionnaires within a week, sealed in an envelope.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS; version 23) and the Analysis of Model Structures (AMOS; version 20). Confirmatory factor analyses, involving principal components analysis (PCA) extraction and promax rotation, were used to assess the construct validity of the Malay ATTS questionnaire. Ten- and 11-factor models were tested based on the findings of past validation studies.24,29 Items with a <0.40 factor loading were excluded from further analysis.

Model fit indices were employed in a confirmatory factor analysis. This included chi-square-value/degree of freedom (χ2/df < 2.00),39 normed fit index (NFI ≥ 0.95),40 Tucker-Lewis index (TLI ≥ 0.95),40 parsimonious normed fit index (PNFI ≥ 0.50),41 root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < 0.05),42 and test of RMSEA significance (PCLOSE ≥ 0.05).

Cronbach’s α (≥0.70)43,44 was employed to assess the overall internal consistency of the scale and its subscales. Items that contributed to low α coefficients were excluded from further analysis.

Approvals

This research obtained ethical approval from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-14-1805-22032) and the Research Ethics Committee, National University of Malaysia (NN-035-2015). The authors complied with the required ethical standards (see Figure 1).45

Figure 1.

Workflow of the translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation process of the English ATTS to the adapted Malay ATTS.

Note. ATTS = Attitudes Toward Suicide.

Results

Participant Characteristics

There were 325 randomly selected participants. The final sample size for this validation was 262 participants (80.6%), with 26 (8.0%) dropouts and 37 (11.4%) excluded listwise due to missing data. The researchers did not rectify incomplete samples, due to confidentiality and the absence of identifiers in the responses. Participants’ demographics are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Healthcare personnel in the Study (n = 262).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean age (SD) | 32.12 (5.61) |

| Min-max | 22-60 |

| Sex | |

| Female | 187 (71.9) |

| Male | 73 (28.1) |

| Race | |

| Malay | 233 (90.0) |

| Chinese | 16 (6.2) |

| Indian | 8 (3.0) |

| Others | 2 (0.8) |

| Religion | |

| Islam | 234 (91.1) |

| Buddhist | 13 (5.1) |

| Christian | 5 (1.9) |

| Hindu | 5 (1.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 186 (71.5) |

| Single | 64 (24.6) |

| Divorced/separated | 7 (2.7) |

| Widowed | 3 (1.2) |

| Education | |

| Secondary school | 57 (22.0) |

| Diploma | 143 (55.0) |

| Degree | 43 (16.5) |

| Master’s/PhD | 17 (6.5) |

| Occupation | |

| Nurse | 119 (49.3) |

| Hospital attendant | 58 (24.1) |

| Medical officer and specialist | 46 (19.0) |

| Assistant medical officer | 18 (7.6) |

| Years of service | |

| Mean years (SD) | 8.36 (4.89) |

| Min-max | 6 mo, 21.25 y |

| No. of suicidal patients cared for | |

| None | 100 (38.8) |

| 1-10 | 94 (36.4) |

| 11-20 | 31 (12.0) |

| 21-30 | 9 (3.5) |

| 31-40 | 7 (2.7) |

| >40 | 17 (6.6) |

| Have attended training on suicide management | |

| Yes | 41 (15.8) |

| No | 218 (84.2) |

| Need more training in handling suicidal patient | |

| Yes | 222 (85.7) |

| No | 37 (14.3) |

Note. Number (n) is based on available information and is reported over total respondents (N = 262). The remaining unreported number is the missing value.

Validity Analysis

The minimum amount of data required for factor analysis was met, with more than 7 cases per questionnaire item. Factorization, through the use of PCA using promax rotation, revealed an acceptable Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.73), which is above the recommended value of 0.60. Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2(666) = 2210.97, P < .001. The diagonals of the anti-image correlation matrix of all items were above 0.50, thus supporting the inclusion of each item in the factor analysis. In addition, the communalities for all items were above 0.40 (see Table 2), suggesting reasonable factorability. Given these overall indicators, factor analysis was performed on all 37 items of the Malay ATTS questionnaire.

Table 2.

Explained Variance, Factor Loadings, and Communalities Based on a Principal Components Analysis With Promax Rotation for 30 Items From the Adapted Malay ATTS Questionnaire (n = 262).

| Item No. | Item | Explained variance, % | Factor loading | Communality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 63.238 | |||

| Factor 1: Ability to understand and accept suicide | 14.547 | |||

| 18 | Suicide a relief Membunuh diri kadang-kadang boleh . . . |

0.798 | 0.655 | |

| 16 | Situation where suicide is the only solution Terdapat situasi di mana satu-satunya . . . |

0.765 | 0.606 | |

| 17 | Could express suicide wish without meaning it—myself Saya boleh menyatakan bahawa . . . |

0.696 | 0.557 | |

| 34 | Right to commit suicide—others Sesiapa pun berhak . . . |

0.655 | 0.530 | |

| 5 | Suicide acceptable way to end incurable disease—others Membunuh diri adalah cara yang boleh . . . |

0.626 | 0.556 | |

| 20 | Consider commit suicide if severe incurable disease—myself Saya akan mempertimbangkan . . . |

0.530 | 0.569 | |

| Factor 2: Suicide among the young and tabooing | 9.502 | |||

| 19 | Suicide among young people puzzling Sukar untuk memahami . . . |

0.804 | 0.696 | |

| 13 | Should or would rather not talk about Membunuh diri adalah perkara . . . |

0.735 | 0.643 | |

| Factor 3: Believability of suicidal threats | 6.423 | |||

| 12 | People who make suicidal threats seldom complete suicide Mereka yang mengancam . . . |

0.833 | 0.733 | |

| 33 | Communication not serious Mereka yang bercakap tentang . . . |

0.770 | 0.660 | |

| Factor 4: Loneliness and avoidance | 5.331 | |||

| 25 | Loneliness a main factor for suicide—others Kesunyian merupakan sebab utama . . . |

0.870 | 0.663 | |

| 14 | Loneliness a factor for suicide—myself Kesunyian boleh menjadi sebab . . . |

0.647 | 0.693 | |

| 23 | Most people avoid talking about suicide Kebanyakan orang mengelak . . . |

0.585 | 0.514 | |

| Factor 5: Judgment and ability to help | 4.780 | |||

| 2 | Suicide can never be justified Membunuh diri tidak boleh . . . |

0.805 | 0.673 | |

| 3 | Suicide among the worst things to do to relatives Membunuh diri merupakan perkara . . . |

0.741 | 0.612 | |

| 1 | Can always help Biasanya kita mempunyai kemampuan . . . |

0.534 | 0.645 | |

| Factor 6: Nature of suicidal ideation | 4.348 | |||

| 10 | Suicide considered for a long time Biasanya seseorang sudah lama . . . |

0.736 | 0.596 | |

| 11 | Risk to evoke suicidal thoughts if asked about Terdapat risiko untuk membangkitkan . . . |

0.690 | 0.551 | |

| 21 | Once someone has suicidal thoughts, will always have it Apabila seseorang mempunyai fikiran . . . |

0.581 | 0.663 | |

| Factor 7: Acceptability of assisted suicide | 4.058 | |||

| 29 | Get help to commit suicide if severe, incurable disease—others Seseorang yang menghidap penyakit . . . |

0.773 | 0.680 | |

| 36 | Get help to commit suicide if severe, incurable disease—myself Saya ingin mendapatkan bantuan . . . |

0.700 | 0.675 | |

| Factor 8: Suicide as a way of communication | 3.854 | |||

| 7 | Suicide as revenge/punishment Kebanyakan percubaan membunuh diri . . . |

0.760 | 0.639 | |

| 26 | Suicide as cry for help Percubaan membunuh diri merupakan . . . |

0.583 | 0.650 | |

| 15 | Everyone has considered suicide at any one time Hampir semua orang pernah . . . |

0.461 | 0.646 | |

| Factor 9: Incomprehensibility | 3.523 | |||

| 28 | Family has no idea Biasanya ahli keluarga . . . |

0.928 | 0.738 | |

| 27 | Not understandable that people can take their lives Secara keseluruhannya, saya . . . |

0.522 | 0.658 | |

| Factor 10: Normality of suicide | 3.463 | |||

| 31 | Anyone can commit suicide Sesiapa pun boleh . . . |

0.753 | 0.668 | |

| 32 | Suicide understandable if severe incurable disease Saya boleh memahami . . . |

0.602 | 0.559 | |

| Factor 11: Duty to prevent and mental illness | 3.409 | |||

| 9 | Duty to restrain a suicidal act Adalah menjadi tugas . . . |

0.698 | 0.558 | |

| 8 | Suicide attempters usually mentally ill Mereka yang membunuh diri . . . |

0.682 | 0.687 |

Note. ATTS = Attitudes Toward Suicide.

PCA examined the solutions for 10 and 11 factors using promax rotation. The initial 11-factor solution was preferred, as it explained a higher percentage of cumulative variance (57.55%) compared with the 10-factor solution (54.63%), and more items with insufficient primary loadings (>0.40) were found for the 10-factor solution.

PCA was conducted again on the 11-factor solution using promax rotation after eliminating 7 items from further analysis due to (1) primary factor loadings of less than 0.40 (items 24, 30, and 37) and (2) contribution to low α coefficient in the subfactors (items 4, 6, 22, and 35). The results revealed that the 11 factors explained 63.24% of the variance. All items had primary loadings above 0.40 (see Table 2).

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to test the model fit for the 11-factor solution, and compare it with the 10-factor solution. The results demonstrate that both models met the fit values with a χ2/df ratio (1.79 and 1.58, respectively) and PCLOSE (0.39; 0.92) indices. The 11-factor model also demonstrated a goodness-of-fit according to the RMSEA (0.04) and PNFI (0.53) indices. However, it failed to meet the cutoff values required for NFI and TLI indices (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Goodness-of-Fit Indicators for the 10- and 11-Factor Solutions for the 30-Item Adapted Malay ATTS (n = 262).

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | χ2 diff | NFI | TLI | PNFI | RMSEA | 90% CI | PCLOSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10-factor | 696.352* | 389 | 1.791 | 0.636 | 0.724 | 0.499 | 0.052 | 0.045-0.058 | 0.388 | |

| 11-factor | 552.273* | 350 | 1.578 | 144.079 | 0.700 | 0.804 | 0.527 | 0.044 | 0.037-0.051 | 0.923 |

Note. ATTS = Attitudes Toward Suicide; NFI = normed fit index; TLI = Tucker-Lewis index; PNFI = parsimonious normed fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; CI = confidence interval.

p < .001.

Reliability Analysis

The Cronbach’s α for the domains ranged from 0.32 to 0.76. The overall Cronbach’s α for the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire was 0.72 (see Table 4), thus indicating that these items measured the same construct or content.46 Descriptive analysis of the questionnaire’s items and factors is shown in Table 4. The least endorsed item was “People do have the right to take their own lives,” while the most endorsed item was “It is a human duty to try to stop someone from committing suicide.” Items 7, 10, 11, 12, 15, 23, 32, and 33 had more than 20% of the respondents choosing the “Undecided” option.

Table 4.

Descriptive Statistics for the 11 Adapted Malay ATTS Factors (n = 262).

| Domain | Median (IQR)a | Min (max)a | Range | α | Question No. | Agree, n (%) | Undecided, n (%) | Disagree, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ability to understand and accept suicide | 11.00 (5.25) | 6.00 (26.00) | 20.00 | 0.76 | 5 | 19 (7.3) | 14 (5.3) | 229 (87.4) |

| 16 | 33 (12.6) | 21 (8.0) | 208 (79.4) | |||||

| 17 | 20 (7.6) | 48 (18.3) | 194 (74.0) | |||||

| 18 | 16 (6.1) | 26 (9.9) | 220 (84.0) | |||||

| 20 | 36 (13.7) | 29 (11.1) | 197 (75.2) | |||||

| 34 | 9 (3.4) | 19 (7.3) | 234 (89.3) | |||||

| 2. Suicide among the young and tabooing | 6.00 (3.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.52 | 13 | 59 (22.5) | 25 (9.5) | 178 (67.9) |

| 19 | 139 (53.1) | 41 (15.6) | 82 (31.3) | |||||

| 3. Believability of suicidal threats | 6.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.66 | 12 | 85 (32.4) | 65 (24.8) | 112 (42.7) |

| 33 | 55 (21.0) | 85 (32.4) | 122 (46.6) | |||||

| 4. Loneliness and avoidance | 9.00 (4.00) | 4.00 (15.00) | 11.00 | 0.52 | 14 | 87 (33.2) | 33 (12.6) | 142 (54.2) |

| 23 | 149 (56.9) | 64 (24.4) | 49 (18.7) | |||||

| 25 | 111 (42.4) | 33 (12.6) | 118 (45.0) | |||||

| 5. Judgment and ability to help | 12.00 (2.00) | 3.00 (15.00) | 12.00 | 0.58 | 1 | 219 (83.6) | 31 (11.8) | 12 (4.6) |

| 2 | 167 (63.7) | 43 (16.4) | 52 (19.8) | |||||

| 3 | 237 (90.5) | 4 (1.5) | 21 (8.0) | |||||

| 6. Nature of suicidal ideation | 10.00 (4.00) | 4.00 (15.00) | 11.00 | 0.47 | 10 | 139 (53.1) | 60 (22.9) | 63 (24.0) |

| 11 | 140 (53.4) | 59 (22.5) | 63 (24.0) | |||||

| 21 | 144 (55.0) | 46 (17.6) | 72 (27.5) | |||||

| 7. Acceptability of assisted suicide | 4.00 (3.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.57 | 29 | 37 (14.1) | 20 (7.6) | 205 (78.2) |

| 36 | 34 (13.0) | 41 (15.6) | 187 (71.4) | |||||

| 8. Suicide as communication | 8.00 (4.00) | 3.00 (14.00) | 11.00 | 0.50 | 7 | 57 (21.8) | 62 (23.7) | 143 (54.6) |

| 15 | 80 (30.5) | 56 (21.4) | 126 (48.1) | |||||

| 26 | 95 (36.3) | 40 (15.3) | 127 (48.5) | |||||

| 9. Incomprehensibility | 8.00 (2.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.46 | 27 | 153 (58.4) | 34 (13.0) | 75 (28.6) |

| 28 | 190 (72.5) | 28 (10.7) | 44 (16.8) | |||||

| 10. Normality of suicide | 7.00 (3.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.36 | 31 | 140 (53.4) | 21 (8.0) | 101 (38.5) |

| 32 | 155 (59.2) | 59 (22.5) | 48 (18.3) | |||||

| 11. Duty to prevent and mental illness | 8.00 (3.00) | 2.00 (10.00) | 8.00 | 0.32 | 8 | 141 (53.8) | 21 (8.0) | 100 (38.2) |

| 9 | 239 (91.2) | 9 (3.4) | 14 (5.3) |

Note. ATTS = Attitudes Toward Suicide; IQR = interquartile range.

Higher scores indicate agreement on the factor/domain.

Discussion

The study findings demonstrate that healthcare personnel may have different categorical constructs on suicide compared with previously tested populations.24,29,33,47 It also sets a milestone in the development of a suicide attitude questionnaire in Malaysia.

In terms of its validity, the item loadings of the adapted 11-factor Malay ATTS questionnaire varied widely from previous studies. Constructs in the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire suggest a distinctive health care viewpoint on suicide attitude, when compared with studies tested on a Western European general population,24 and college students in Asia 29,33 and Uganda.47 For example, the items “People who make suicidal threats seldom complete suicide” and “Those who talk about suicide will not do it” were grouped under the “Common/Normal” factor in the original ATTS questionnaire, but emerged as a distinctive factor in the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire under “Believability of Suicide Threats.” This may reflect on the experience and decisions that healthcare personnel need to undertake when encountering suicidal patients, compared with the general population. The factors “Acceptability of Assisted Suicide,” “The Nature of Suicidal Ideation,” and “Duty to Prevent and Mental Illness” also emerged to indicate issues that surround the health care establishment.

Cultural and religious differences may contribute to the factor loading patterns of the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire items. The factor “Loneliness and Avoidance” may be indicative of isolation and the taboo surrounding suicide in Malaysia, especially among Muslims,33,34 who comprised the majority of respondents. The factor “Ability to Understand and Accept Suicide” in the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire merged items from the “Resignation” and “Right to Suicide” factors in the original ATTS questionnaire. This may indicate that those who disagreed with the right to suicide could also be less understanding toward suicidal patients’ reasons for wanting to die. Further explorations into the right-to-die issue are important, as healthcare personnel who expressed a permissive right-to-die attitude reported less competency in suicide-related interventions48 and were associated with personal factors, such as suicide ideation history25 and lower/nonendorsement of a religious belief.49,50

Confirmatory factor analysis yielded mixed findings, where requirements for absolute fit indices, such as χ2/df, RMSEA, and PCLOSE, were met, but the cutoff values recommended for relative fit indices, such as TLI and NFI, were not. This may be due to the relatively large number of variables51 resulting in poor fit values. The multidimensional nature of suicide attitudes24 may also contribute to this.

In terms of reliability analysis, the adapted questionnaire demonstrated an acceptable overall Cronbach’s α of more than 0.70, thus indicating the internal reliability of the instrument. When compared with Salander Renberg and Jacobsson24 and Ji et al,29 the Cronbach’s α value was slightly higher. However, there was a large variation in the internal consistency of factors, ranging from 0.32 to 0.76. This variation also surfaced in other suicide attitude instruments (e.g., α coefficient range of 0.26-0.83 in Domino et al,52 0.48-0.85 in Rogers and DeShon,53 0.38-0.86 in Salander Renberg and Jacobsson,24 0.57-0.74 in Xiang et al,33 and 0.31-0.78 in Ji et al29), suggesting that attitude toward suicide could be a highly sensitive issue resulting in conflicting and varied responses from participants,24 especially in a cultural setting where suicide is stigmatized.47

Finally, analysis of response proportions to each item revealed that 8 items consisted of at least one-fifth of the participants choosing the “Undecided” option. Response fatigue, or low motivation, could be ruled out as the reason, because the position of these items ranged from the beginning, middle, and end of the questionnaire.54 Perhaps healthcare personnel in this study felt a lack of knowledge or information to assess the believability level of a suicidal patient’s communication (items 12 and 33) and the private nature of suicidal thoughts (items 7, 10, 11, and 15), and experienced a conflict between sympathizing with a terminally ill patient’s wish to die and disagreement with the right to die (item 32), or were ambivalent about suicide as a taboo topic for discussion (item 23).

Strengths and Limitations

As the first study in Malaysia to cross-culturally adapt and validate a suicide attitude questionnaire, this study demonstrated methodological vigor by employing random sampling to ensure representativeness of the data. Participants’ heterogeneity was also achieved, as is attested by the participants’ age range, department, occupation, and experience in the health care sector and in handling suicidal patients. As for its limitations, the drop-out rate and missing data could have contributed to the response bias, which was not examined. Nearly half of the respondents were inexperienced in managing suicidal patients; therefore, their attitudes may not be shaped by concrete encounters with suicidal individuals. However, we still consider their responses to be valid, as attitudes could constitute preconceived ideas, which may or may not be modified by experience. This study focused on healthcare personnel from 2 general hospitals, while providers from community and private settings were not represented. Future studies employing different settings and target groups are needed to further explore and improve the psychometric rigor of the adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire, so that comparisons can be made.

Conclusion

The adapted Malay ATTS questionnaire demonstrated adequate psychometric properties for use among healthcare personnel in Malaysia. Underlying factors that are distinctive to healthcare personnel were revealed, thus indicating the questionnaire’s suitability for administration to this population.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to convey their gratitude to the Director General of the Ministry of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this article, and the director, heads of departments, and staff of the UKM Medical Centre and Putrajaya Hospital. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Ellinor Salander Renberg (Umeå University, Sweden) for permission to use the Attitudes Toward Suicide (ATTS) and for clarifications given during the translation process, and Ms Lee Shoo Thien, a statistician, for statistical advice.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: LHW proposed the study to be carried out. CSS conducted the data collection and undertook the statistical analyses. CSS and LHW wrote the first draft of the manuscript with advice from a statistician. All authors edited, contributed to, and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by the Research University Grant, National University of Malaysia (Grant No.: GUP-2014-065).

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Preventing suicide: a global imperative. http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/. Published 2014. Accessed January 25, 2017.

- 2. Beautrais AL. Suicide in Asia. Crisis. 2006;27(2):55-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malaysian Psychiatric Association. Suicide—It’s an SOS! http://www.psychiatry-malaysia.org/article.php?aid=504. Accessed August 29, 2016.

- 4. Ibrahim N, Amit N, Suen MW. Psychological factors as predictors of suicidal ideation among adolescents in Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e110670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ali NH, Zainun KA, Bahar N, et al. Pattern of suicides in 2009: data from the National Suicide Registry Malaysia. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2014;6(2):217-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armitage CJ, Panagioti M, Rahim WA, Rowe R, O’Connor RC. Completed suicides and self-harm in Malaysia: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2015;37(2):153-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maniam T. Suicide and undetermined violent deaths in Malaysia, 1966-1990: evidence for the misclassification of suicide statistics. Asia Pac J Public Health. 1995;8(3):181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Maniam T, Chan LF. Half a century of suicide studies—a plea for new directions in research and prevention. Sains Malaysiana. 2013;42(3):399-402. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Da Cruz D, Pearson A, Saini P, et al. Emergency department contact prior to suicide in mental health patients. Emerg Med J. 2011;28(6):467-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgess P, Pirkis J, Morton J, Croke E. Lessons from a comprehensive clinical audit of users of psychiatric services who committed suicide. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(12):1555-1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sinniah A, Maniam T, Oei TP, Subramaniam P. Suicide attempts in Malaysia from the year 1969 to 2011. Sci World J. 2014;2014:718367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saunders KE, Hawton K, Fortune S, Farrell S. Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;139(3):205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hawton K, Taylor TL, Saunders KE, Mahadevan S. Clinical care of deliberate self-harm patients: an evidence-based approach. In O’Connor RC, Platt S, Gordon J, eds. International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2011:329-351. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor TL, Hawton K, Fortune S, Kapur N. Attitudes towards clinical services among people who self-harm: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(2):104-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reynders A, Kerkhof AJ, Molenberghs G, Van Audenhove C. Stigma, attitudes, and help-seeking intentions for psychological problems in relation to regional suicide rates. Suicide Life-Threat. 2016;46(1):67-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osteen PJ, Frey JJ, Ko J. Advancing training to identify, intervene, and follow up with individuals at risk for suicide through research. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3):S216-S221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pringle B, Colpe LJ, Heinssen RK, et al. A strategic approach for prioritizing research and action to prevent suicide. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(1):71-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Isgandarova N. Physician-assisted suicide and other forms of euthanasia in Islamic spiritual care. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2015;69(4):215-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Webster Rudmin F, Ferrada-Noli M, Skolbekken JA. Questions of culture, age and gender in the epidemiology of suicide. Scand J Psychol. 2003;44(4):373-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kodaka M, Poštuvan V, Inagaki M, Yamada M. A systematic review of scales that measure attitudes toward suicide. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;57(4):338-361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Diekstra RF, Kerkhof AJ. Attitudes toward suicide: development of a suicide attitude questionnaire (SUIATT). In: Current Issues of Suicidology. Berlin, Germany; Springer; 1988:462-476. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Domino G, Gibson L, Poling S, Westlake L. Students’ attitudes towards suicide. Soc Psychiatr. 1980;15(3):127-130. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Domino G, Moore D, Westlake L, Gibson L. Attitudes toward suicide: a factor analytic approach. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38(2):257-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Renberg ES, Jacobsson L. Development of a questionnaire on attitudes towards suicide (ATTS) and its application in a Swedish population. Suicide Life-Threat. 2003;33(1):52-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kodaka M, Inagaki M, Poštuvan V, Yamada M. Exploration of factors associated with social worker attitudes toward suicide. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2013;59(5):452-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kodaka M, Inagaki M, Yamada M. Factors associated with attitudes toward suicide. Crisis. 2013;34:420-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Norheim AB, Grimholt TK, Ekeberg Ø. Attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in outpatient clinics among mental health professionals in Oslo. BMC Psychiat. 2013;13(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Norheim AB, Grimholt TK, Loskutova E, Ekeberg O. Attitudes toward suicidal behaviour among professionals at mental health outpatient clinics in Stavropol, Russia and Oslo, Norway. BMC Psychiat. 2016;16(1):268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ji NJ, Hong YP, Lee WY. Comprehensive psychometric examination of the attitudes towards suicide (ATTS) in South Korea. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2016;10(1):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim K, Park JI. Attitudes toward suicide among college students in South Korea and the United States. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2014;8(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Medina CO, Jegannathan B, Dahlblom K, Kullgren G. Suicidal expressions among young people in Nicaragua and Cambodia: a cross-cultural study. BMC Psychiat. 2012;12(1):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mofidi N, Ghazinour M, Salander-Renberg E, Richter J. Attitudes towards suicide among Kurdish people in Iran. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(4):291-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Foo XY, Alwi MN, Ismail SI, Ibrahim N, Osman ZJ. Religious commitment, attitudes toward suicide, and suicidal behaviors among college students of different ethnic and religious groups in Malaysia. J Relig Health. 2014;53(3):731-746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eskin M, Kujan O, Voracek M, et al. Cross-national comparisons of attitudes towards suicide and suicidal persons in university students from 12 countries. Scand J Psychol. 2016;57(6):554-563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Borsa JC, Damásio BF, Bandeira DR. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of psychological instruments: some considerations. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto). 2012;22(53):423-432. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hair JE, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate Data Analysis: With Readings. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kline P. Psychometrics and Psychology. London, England: Academic Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cattell RB. The Scientific Use of Factor Analysis in Behavioral and Life Sciences. New York: Springer; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed. New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1-55. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1989;105(3):430-445. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen F, Curran PJ, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36(4):462-494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297-334. [Google Scholar]

- 44. DeVellis R. Scale Development: Theory and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Musa R, Fadzil MA, Zain ZA. Translation, validation and psychometric properties of Bahasa Malaysia version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS). ASEAN J Psychiat. 2007;8(2):82-89. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hjelmeland H, Kinyanda E, Knizek BL, Owens V, Nordvik H, Svarva K. A discussion of the value of cross-cultural studies in search of the meaning(s) of suicidal behavior and the methodological challenges of such studies. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(1):15-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neimeyer RA, Fortner B, Melby D. Personal and professional factors and suicide intervention skills. Suicide Life-Threat. 2001;31(1):71-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rathor MY, Rani MF, Shahar MA, et al. Attitudes toward euthanasia and related issues among physicians and patients in a multi-cultural society of Malaysia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3(3):230-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stack S, Kposowa AJ. Religion and suicide acceptability: a cross-national analysis. J Sci Study Relig. 2011;50(2):289-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kenny DA, McCoach DB. Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling. 2003;10(3):333-351. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Domino G, Macregor JC, Hannah MT. Collegiate attitudes toward suicide: New Zealand and United States. OMEGA. 1989;19(4):351-364. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rogers JR, DeShon RP. Cross-validation of the five-factor interpretive model of the suicide opinion questionnaire. Suicide Life-Threat. 1995;25(2):305-309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sturgis P, Roberts C, Smith P. Middle alternatives revisited: how the neither/nor response acts as a way of saying “I don’t know”? Sociol Method Res. 2014;43(1):15-38. [Google Scholar]