Abstract

Existing literature on rumination has predominately focused on depressive rumination; thus, there is little research directly comparing different forms of rumination as correlates of psychopathological outcomes. The present study investigated anger and depressive rumination as correlates of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Cross-sectional confirmatory factor analyses on data from 764 young adults from the Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study indicated that anger and depressive rumination were separable at the latent variable level, and were both associated with lifetime symptoms of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. However, depressive rumination was more strongly associated with psychopathology than was anger rumination. Further analysis indicated that depressive rumination was independently associated with internalizing psychopathology, whereas associations between anger rumination and psychopathology were predominately due to shared variance with depressive rumination. Anger rumination was independently associated with externalizing psychopathology in women and was inversely associated with internalizing psychopathology in men. This result supports the clinical relevance of ruminative thought processes and the potential differential utility of anger and depressive content for understanding internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

Keywords: Rumination, Brooding, Anger, Sadness, Psychopathology, Depression

Rumination, a pattern of repetitive, self-focused thought in response to an emotional state, plays a critical role in well-being. Heightened ruminative tendencies are associated with increased anger and sadness (Thomsen, 2006), thoughts of shame (Gilbert, Cheung, Irons, & McEwan, 2005), and poor sleep quality (Thomsen, Mehlsen, Christensen, & Zachariae, 2003). Rumination also has significant associations with a wide range of psychopathology. People who habitually ruminate are more likely to later develop later major depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007), anxiety symptoms (Calmes & Roberts, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), and alcohol abuse problems (women only; Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002).

Although rumination appears to be a transdiagnostic correlate of multiple forms of psychopathology (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; Johnson et al., 2016), most studies examining rumination and psychopathology have focused on depressive rumination. Less is known about the role of other subtypes of rumination, such as anger rumination. However, the few studies that have included measures of anger rumination along with depressive rumination suggest that anger and depressive rumination show relations of different magnitudes with psychopathology symptoms. For example, Ciesla et al. (2011) found that anger rumination is associated with heightened alcohol consumption on a weekly basis, whereas depressive rumination is not. Baer and Sauer (2011) found that borderline personality disorder features are more strongly associated with anger rumination (controlling for current symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, partial r = .64, p < .001) than depressive rumination (partial r = .35, p < .001; Baer & Sauer, 2011). Depressive and anger rumination also have unique relations with clinically relevant constructs when included in the same regression model. In two separate studies (one with healthy adults and another with adolescents with conduct problems), Peled and Moretti (2007; 2010) found that anger rumination, but not depressive rumination, was independently associated with anger, overt aggression, and relational aggression. In contrast, they found that depressive rumination, but not anger rumination, had a positive association with depressive symptoms and a negative association with overt aggression when controlling for anger rumination. Together, this research suggests that rumination about different content (i.e., focused on sadness versus anger) may be differentially associated with psychopathology.

However, studies that have examined anger and depressive rumination together have focused primarily on individual outcomes (e.g., weekly drinking habits; Ciesla et al., 2011) or discrete disorders (e.g., depression; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), rather than transdiagnostic relations between subtypes of rumination and domains of psychopathology (i.e., internalizing and externalizing psychopathology). Transdiagnostic approaches examine common features (e.g., shared genetic liability, temperament), which distinguish general psychopathology from normality and contribute to both internalizing (e.g., major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder) and externalizing psychopathology (e.g., antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder; Lilienfeld, 2003; Weiss, Süsser, & Catron, 1998). Despite the overlap in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, the correlations among internalizing disorders and among externalizing disorders are higher than correlations between them (Krueger, Caspi, Moffitt, & Silva, 1998), suggesting that there is a meaningful distinction between these forms of psychopathology. Thus, examining broad-band specific features, or features that differentiate internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, can help inform why some individuals may be at greater risk for internalizing disorders than externalizing disorders and vice versa (Lilienfeld, 2003; Weiss et al., 1998). Examining internalizing and externalizing disorders simultaneously enables an investigation of whether subtypes of rumination are common features of psychopathology — and thus associated with the common variance between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology — or broad-band specific features that are differentially associated with the two forms of psychopathology.

The Present Study

The present study extends the literature by investigating both anger and depressive rumination as cross-sectional correlates of lifetime internalizing and externalizing psychopathology symptom endorsement in a sample of young adults. To improve transparency in investigating these associations, we prospectively registered our introduction, hypotheses, and method sections with the Open Science Framework (see www.osf.io/5zpve/ for more details).

We predicted that anger and depressive rumination measures would be best described by two correlated factors (Ciesla et al., 2011; Peled & Moretti, 2007, 2010) rather than a single factor (Selby et al., 2008; Selby, Anestis, Bender, & Joiner, 2010). We then investigated whether focusing on the process (one-factor) versus content (sadness versus anger; two-factor) of rumination has implications for our understanding of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Given previous transdiagnostic research on depressive rumination (Aldao, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Schweizer, 2010) and the strong relationship between anger and depressive rumination (r = .57, p < .01; Baer & Sauer, 2011; r = .72, p < .01; Peled & Moretti, 2007), we hypothesized that depressive and anger rumination would be associated with both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. However, in addition to expecting that an individual’s tendency to engage in ruminative thought processes would be associated with greater psychopathology, we also hypothesized that the emotional focus (sadness versus anger) of rumination would be differentially associated with psychopathology. Specifically, we predicted that depressive rumination and anger rumination would have unique associations with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, respectively. This prediction is consistent with research linking depressive rumination to mood disorders (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012), and anger rumination to aggression and hostility (Borders, Earleywine, & Jajodia, 2010; Maxwell, 2004) but not depressive symptoms, after controlling for depressive rumination (Peled & Moretti, 2007, 2010).

We conducted these analyses allowing for potential gender differences in the associations between depressive rumination, anger rumination, and psychopathology. Previous research has noted higher levels of depressive rumination in women than in men (Johnson & Whisman, 2013). In contrast, the literature suggests that there are no gender differences in levels of anger rumination (Barber, Maltby, & Macaskill, 2005; Hogan & Linden, 2004; Maxwell, 2004; Peled & Moretti, 2010), although findings are inconsistent (Peled & Moretti, 2007; Sukhodolsky, Golub, & Cromwell, 2001). Gender differences in psychopathology have also been noted: Internalizing disorders are more prevalent in women, whereas externalizing disorders are more prevalent in men (Caspi et al., 2014; Eaton et al., 2012). Beyond mean differences, some studies have also found that gender moderates rumination’s relation to alcohol problems, with rumination predicting later alcohol problems in women only (Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002). However, other studies have found no gender differences in rumination’s relation to depression, anxiety, aggression, and alcohol problems (Calmes & Roberts, 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema & Harrell, 2002; Peled & Moretti, 2007). Given these inconsistencies in the prior literature, we included gender as a potential moderator as a more exploratory aim of the current study.

Method

Participants

Participants were 764 young adults (362 male, 402 female) from 382 same-sex twin pairs who participated in the ongoing Colorado Longitudinal Twin Study (LTS), a study of emotional, cognitive, and behavioral development from infancy to adulthood. The foundational sample of 483 LTS families were identified by the Colorado Department of Health’s Division of Vital Statistics as having same-sex twins born between 1986 and 1990, living within two hours of Boulder, CO, and meeting additional criteria such as the twins having normal birth weights and gestational periods. We report on data from two studies that LTS participants completed at approximately age 23: a longitudinal study conducted by the Center for Antisocial Drug Dependence (CADD) at the University of Colorado and a separate study of executive functions and self-regulation (for additional information, see Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, & Corley, 2013; Rhea, Gross, Haberstick, & Corley, 2006). The majority (98.20%) of the 764 participants completed both the rumination and psychopathology measures; one participant completed just the rumination measures, and 13 participants completed just the psychopathology measures. The mean age of the individuals upon completion of both the rumination and psychopathology measures was 22.8 (standard deviation ±1.3, range 21.0–28.0), and participants usually completed the psychopathology and rumination measures within a month of each other (mean age difference = 0.05 years, standard deviation ±0.2). The full sample was 92.1% Caucasian, 5.2% Multiracial, 0% Black/African-American, 1.3% other, and 1.2% not reported. All research protocols and consent forms were approved by the University of Colorado’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Depressive rumination

Measures of rumination were administered as a part of the self-regulation study. Participants completed two measures of depressive rumination: the Rumination-Reflection Questionnaire (RRQ; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), and the 10-item revised version of the Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003). The RRQ is a 24-item scale that measures rumination (RRQ-Ru) and reflection (RRQ-Re) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The RRQ-Ru measures negative self-focused thought (“I tend to ‘ruminate’ or dwell over things that happen to me for a really long time afterward”). In contrast, the RRQ-Re measures self-reflection, or a general tendency to think introspectively (“I’m very self-inquisitive by nature”). Previous work suggests that self-reflection is a construct that is distinct from depressive rumination (Siegle, Moore, & Thase, 2004); when controlling for rumination, self-reflection is unrelated or modestly related to psychopathology whereas rumination maintains robust associations with psychopathology when controlling for self-reflection (Johnson et al., 2016). Thus, the RRQ-Re was not included in the present study. In this sample, as in previous samples (α = .90; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999), the reliability of the RRQ-Ru was high (α = .91).

The 10-item RRS scale (Treynor et al., 2003) is a version of the original RRS (Nolen-Hoeksema and Morrow, 1991) that excludes items that overlap with depression inventories. The 10-item RRS has two subscales, brooding (RRS-B), and reflection (RRS-R). All items on the RRS are focused on how individuals respond when they are feeling “down, sad, or depressed” (Treynor et al., 2003) and are rated on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Unlike the reflection subscale of the RRQ, the RRS-R subscale measures the tendency to reflect on sadness (“I analyze recent events to try to understand why I am depressed”) rather than general introspection. The RRS-B subscale measures negative, self-focused, perseverative thoughts (“I think ‘What am I doing to deserve this?’”). Previous research suggests that the two subscales have adequate reliability (RRS-B, α = .74–77; RRS-R, α = .66–.72; Siegle et al., 2004; Treynor et al., 2003), and this was also true of the current sample (RRS-B, α = .80; RRS-R, α = .80).

Anger rumination

The Anger Rumination Scale (ARS; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001) is a 19-item scale designed to measure recurrent cognitions that emerge during and after an anger episode. ARS items, which are rated on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always), are divided into 4 subscales: angry afterthoughts, thoughts of revenge, angry memories, and understanding causes. The angry afterthoughts subscale measures cognitive rehearsal of the anger episode (“I re-enact the anger episode in my mind after it has happened”), whereas the thoughts of revenge subscale captures desired retribution (“I have long living fantasies of revenge after the conflict is over”). The angry memories subscale assesses thoughts of past anger episodes (“I think about certain events from a long time ago and they still make me angry”), and the understanding of causes subscale refers to thoughts about the causes of the anger episode (“I think about the reasons people treat me badly”). Previous work has found good internal consistency for the total scale (α = .93) and subscales (α = .77–.86; Sukhodolsky et al., 2001). In this sample, the full-scale Cronbach’s alpha was .93, and the Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales ranged from .68 to .86.

For both the anger and depressive rumination measures, we calculated total or subscale scores if participants answered at least 80% of the items on the questionnaire or subscale. Scores were calculated by averaging the items answered after reverse-scoring items when appropriate.

Psychopathology

Measures of psychopathology were administered over the phone as a part of the CADD study. Participants completed the major depressive disorder (MDD), generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) modules from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule – IV (DIS-IV; Robins et al., 2000). This structured interview is designed to diagnose the major psychiatric disorders found in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Given a low prevalence of current symptoms and diagnoses in this sample, lifetime symptoms and diagnoses were used for both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. For internalizing psychopathology, we used lifetime symptom endorsement from the MDD and GAD modules. Externalizing psychopathology was measured using lifetime symptom endorsement from the ASPD module from the DIS-IV and substance use information from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview – Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM; Cottler, Robins, & Helzer, 1989). The CIDI-SAM is a structured interview used to diagnose abuse and dependence for tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and seven additional classes of illicit drugs (cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, inhalants, PCP, opiates, and sedatives). The present study assessed cannabis use symptoms prior to the legal commercial sale of recreational cannabis in Colorado. There was a low prevalence of dependence symptoms for illicit drugs in our sample; thus, for each person who endorsed illicit drug use, we used the illicit drug class with the highest number of symptoms.

For measures of both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, we created ordinal psychopathology symptom count variables. This enabled us to estimate the underlying liability based on the frequencies within each category and decrease the risk of biased parameter estimates that are typical of highly skewed symptom count variables (Derks, Dolan, & Boomsma, 2004). For internalizing psychopathology (GAD and MDD), tobacco use disorder, and ASPD, a score of 0 indicated no symptoms, 1 indicated symptoms but no diagnosis, and 2 indicated a diagnosis according to the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Problematic substance use involving illicit drugs was coded 0 for no symptoms and 1 for one or more symptoms given the low prevalence rates. Alcohol and cannabis use disorder were scored 0 for no symptoms, 1 for one symptom, 2 for 2–3 symptoms, 3 for 4–5 symptoms, and 4 for 6 or more symptoms (see Table 1 for frequencies).

Table 1.

Psychopathology Symptom Frequencies by Sex

| Symptoms: Females | 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 6+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD | 289 | 47 | 66 | ||

| GAD | 346 | 26 | 30 | ||

| ASPD | 256 | 95 | 51 | ||

| Alcohol Use | 193 | 78 | 72 | 29 | 29 |

| Cannabis Use | 346 | 26 | 13 | 10 | 6 |

| Tobacco Use | 304 | 46 | 51 | ||

| Illicit Drug Use | 376 | 25 | |||

|

| |||||

| Symptoms: Males | 0 | 1 | 2–3 | 4–5 | 6+ |

|

| |||||

| MDD | 285 | 43 | 33 | ||

| GAD | 330 | 26 | 5 | ||

| ASPD | 161 | 104 | 96 | ||

| Alcohol Use | 134 | 60 | 92 | 49 | 26 |

| Cannabis Use | 242 | 50 | 45 | 14 | 10 |

| Tobacco Use | 205 | 66 | 90 | ||

| Illicit Drug Use | 316 | 45 | |||

Note. For tobacco use disorder, GAD, MDD, and ASPD: 1 = symptoms but no diagnosis; 2 = diagnosis according to DSV-IV criteria. For substance use involving illicit drugs: 1 = one or more symptoms. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder. In the present sample, 120 men and 91 women met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol use disorder; 90 men and 51 women met DSM-IV criteria for cannabis use disorder; and 15 men and 18 women met DSM-IV criteria for an illicit drug use disorder.

Statistical Analysis

After visually inspecting the data for univariate outliers, we used a log-transformation of the four anger rumination subscales to improve normality (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material online for skewness, kurtosis, and descriptive statistics for the rumination measures by gender). Structural equation models (SEM) were estimated with Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015). For models that included categorical variables, we used the means and variance adjusted weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimation method, which uses pairwise deletion for participants with missing data on one or more measures. For all other models, we used robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation, which uses full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) for missing data. This method treats missing data as missing at random, uses all available data to compute parameter estimates, and is robust to non-normality (Enders, 2001). As participants were twin pairs, we used Mplus’s TYPE = COMPLEX option to correct for the nonindependence of the twin pairs. This option uses a sandwich estimator to compute standard errors and a scaled chi-square (χ2) that are adjusted for non-independence and robust to non-normality. To conduct nested model comparisons, we used chi-square difference (Δχ2) tests incorporating the scaling factors (Satorra & Bentler, 2001). The significance of specific parameters was determined by p-values for the z-statistic (the ratio of the parameter estimate to its standard error). We used an alpha level of .05 to determine significance for all analyses.

We used the χ2 statistic to assess model fit. Because the χ2 is sensitive to sample size, we also used the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). As recommended by Hu & Bentler (1998), we used a CFI > .95 and RMSEA <.06 as indications of good fit.

Results

Factor Structure of Psychopathology and Rumination

Zero-order correlations for all variables are presented in Table S2 in the Supplemental Material available online. To determine the best-fitting measurement models for each construct, we compared one-factor and two-factor measurement models of psychopathology and rumination separately, allowing men and women to have different model parameters. Then, as a prerequisite for examining sex differences in the relations between rumination and psychopathology, we tested for measurement invariance across sex for each measurement model separately.

Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology

Consistent with previous research, a two-factor internalizing–externalizing model, χ2(26) = 32.18, p = .187, RMSEA = .025 [.000, .050], CFI = .996, fit the data significantly better than a one-factor psychopathology model, χ2(28) = 93.91, p < .001, RMSEA = .079 [.061, .096], CFI = .960; Δχ2(2) = 44.28, p < .001. The correlation between the internalizing and externalizing psychopathology latent variables was .72 (95% CI [.46, .99]) in men, and .44 (95% CI [.30, .58]) in women.

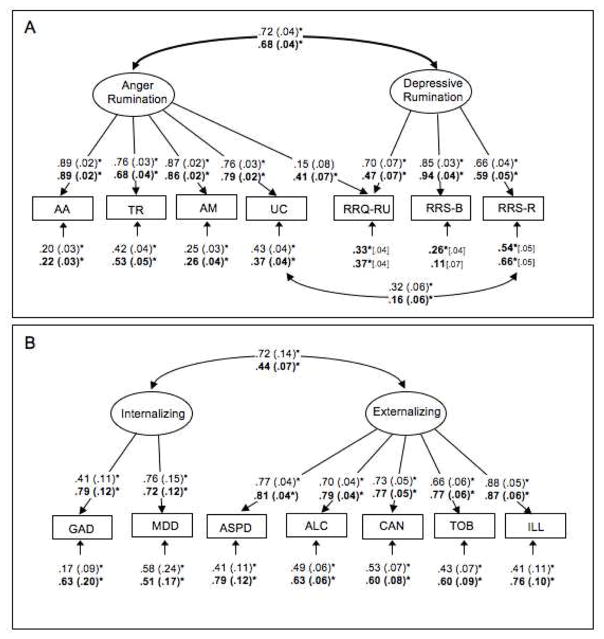

We then tested for factorial invariance across sex. Factorial invariance for categorical variables involves constraining the factor loadings and thresholds to be equal across men and women but allowing the scale factors and factor means to vary. These invariance constraints resulted in a significant decrement in fit for the psychopathology model, Δχ2(13) = 29.16, p = .006. Thus, for all subsequent analyses we used a noninvariance model, in which the factor means and scale factors were invariant across sex (to identify the model), and all other parameters were allowed to vary across sex, χ2(26) = 32.18, p = .187, RMSEA = .025 [.000, .050], CFI = .996 (see Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Measurement models of (A) rumination and (B) psychopathology. Standardized parameters are depicted for men in regular text and women in bold text. Standard errors are in parentheses. Ellipses represent latent variables and rectangles represent manifest variables or individual scales. AA = anger rumination scale – angry afterthoughts; TR = anger rumination scale – thoughts of revenge; AM = anger rumination scale – angry memories; UC = anger rumination scale – understanding causes; RRQ-RU = rumination-reflection questionnaire – rumination; RRS-B = ruminative responses scale – brooding; RRS-R = ruminative responses scale – reflection. GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; MDD = major depressive disorder; ASPD = antisocial personality disorder; ALC = alcohol use disorder, CAN = cannabis use disorder, TOB = tobacco use disorder, ILL = substance use disorder involving illicit drug use. *p<.05.

Are depressive and anger rumination separable constructs?

To examine this question, we evaluated whether anger and depressive rumination measures were best fit by a one-factor, χ2(28) = 365.57, p < .001, RMSEA = .179 [.163, .196], CFI = .871, or two-factor, χ2(26) = 115.56, p < .001, RMSEA = .096 [.078, .114], CFI = .965, model. Consistent with our hypothesis that anger and depressive rumination can be separated by their content, the two-factor model, with a correlation between the factors of .76 (95% CI [.69, .84]) in men and .80 (95% CI [.74, .87]) in women, fit the data significantly better, Δχ2(2) = 172.12, p < .001.

Although the two-factor model fit better than the one-factor model, the fit statistics suggested some misspecification: The CFI indicated good fit, but the RMSEA and chi-square were high. Thus, we examined the residual covariance matrix in conjunction with the rumination items for each questionnaire to ascertain if there were theoretically sensible modifications that would improve fit. Unlike the other subscales, the RRQ-Ru subscale did not prompt participants to focus on either an angry or sad emotion state. Given that the questions on this subscale could have applied to either emotional state, we allowed a complex loading so that this subscale could be predicted by both the anger and depressive rumination factors. There were also similarities between the understanding causes subscale of the ARS and the reflection subscale of the RRS, which both involve thinking about the causes of an emotional state (e.g., RRS-R - “I analyze recent events to try to understand why I am depressed”; UC - “I think about the reasons people treat me badly”). Given these similarities, a residual correlation between these subscales was added to the model. These post-hoc modifications significantly improved model fit, Δχ2(4) = 68.08, p < .001.

As with the psychopathology measurement model, we tested for factorial invariance across men and women. Metric invariance, in which the factor loadings were equated across men and women, did not hold for rumination, Δχ2(7) = 34.35, p < .001. Thus, for all analyses we used a configurally invariant model, in which all parameters except those used to identify the model (i.e., the first factor loading for each latent variable) were allowed to vary across men and women, χ2(22) = 53.37, p < .001, RMSEA = .062 [.041, .083], CFI = .988 (see Figure 1A).

Given that the factor loadings of the measurement models for rumination and psychopathology could not be equated across sex, we present all results separately for men and women. Furthermore, as differences in the relationships between rumination and psychopathology could be an artifact of differences in the measurement models and thus potentially misleading (Reise, Widaman, & Pugh, 1993), we note qualitative differences across sex but did not formally test sex as a moderator of the relationships between rumination and psychopathology.

Relations of Rumination to Psychopathology

Are depressive and anger rumination both associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology?

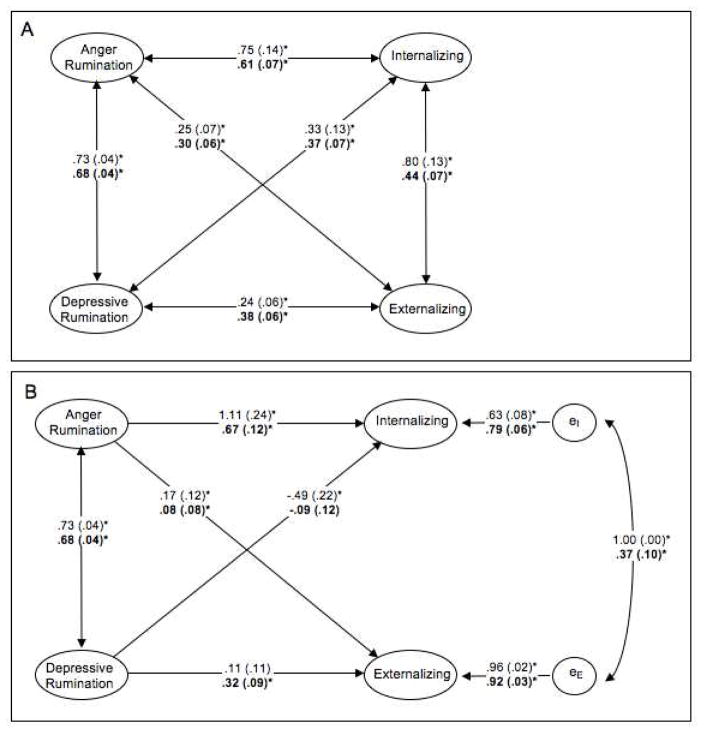

Using the correlational model in Figure 2A, χ2(138) = 189.75, p = .002, RMSEA = .031 [.019, .042], CFI = .976, we examined if anger and depressive rumination have transdiagnostic associations with psychopathology.1 All correlations between rumination and psychopathology were significant (ps < .05), suggesting that both forms of rumination are associated with increased psychopathology.

Figure 2.

Correlational model (panel A) and regression model (panel B) of rumination and psychopathology. Standardized parameters are depicted for men in regular text and women in bold text. Standard errors are in parentheses. Ellipses indicate latent variables. For simplicity, the manifest variables that load on the latent variables are not depicted. The residual correlation between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology for men was bounded so that it could not exceed 1.0. *p<.05.

Are depressive and anger rumination differentially associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology?

The correlational model (see Figure 2A) indicated that depressive rumination’s correlation with internalizing psychopathology (male r = .75; female r = .61) was higher than its correlation with externalizing psychopathology (male r = .25; female r = .30). Constraining these correlations to be equal2 significantly worsened model fit in men, Δχ2(1) = 15.97, p < .001, and women, Δχ2(1) = 14.46, p < .001, suggesting that depressive rumination is more strongly associated with internalizing than with externalizing.

Next we tested if anger rumination was associated equally with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. The correlational model indicated that anger rumination was moderately correlated with both internalizing (male r = .33; female r = .37) and externalizing (male r = .24; female r = .38) psychopathology. Constraining these correlations to be equal did not hurt model fit in men, Δχ2(1) = 0.61, p = .434, nor women, Δχ2(1) = 0.02, p = .896, indicating that anger rumination is associated equally with both forms of psychopathology.

Are internalizing or externalizing psychopathology equally associated with anger and depressive rumination?

Depressive rumination was associated more strongly with internalizing than externalizing psychopathology, yet could still be an equal or worse correlate of internalizing when compared to anger rumination. Thus, we examined if internalizing psychopathology was associated more strongly with depressive or anger rumination. Constraining the correlations between anger and depressive rumination with internalizing to be equal indicated that depressive rumination was associated more strongly with internalizing (male r = .75; female r = .61) than was anger rumination (male r = .33; female r = .37) in both men, Δχ2(1) = 17.17, p < .001, and women, Δχ2(1) = 9.13, p = .003.

Although anger rumination was associated equally with both forms of psychopathology, we hypothesized that anger rumination might still be more strongly associated with externalizing when compared to depressive rumination. To test this hypothesis, we constrained the correlations of externalizing psychopathology with anger rumination (male r = .24; female r = .38) and depressive rumination (male r = .25; female r = .31). Anger rumination and depressive rumination were associated equally with externalizing in both men, Δχ2(1) = 0.08, p = .777, and women, Δχ2(1) = 2.32, p = .128.

Do depressive and anger rumination have independent associations with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology?

Overall, results from the correlation constraints suggest that anger and depressive rumination are both associated with psychopathology. Depressive rumination was associated more strongly with internalizing than externalizing psychopathology, whereas anger rumination was equally associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. However, the constrained correlational models did not give information about the independent associations between depressive rumination with internalizing and externalizing after controlling for anger rumination and vice versa. Thus, we examined a statistically equivalent regression model of psychopathology on anger and depressive rumination, χ2(138) = 189.85, p = .002, RMSEA = .031 [.019, .042], CFI = .975 (see Figure 2B).3 In this model, depressive rumination was associated with internalizing (male β = 1.04, p < .001; female β = 0.67, p < .001) but not externalizing (male β = .17, p = .145; female β = 0.08, p = .324) after controlling for anger rumination. Anger rumination was associated with externalizing in women (β = 0.32, p < .001), but not men (β = 0.11, p = .326), after controlling for depressive rumination. Also, anger rumination was not associated with internalizing above and beyond depressive rumination in women (β = −0.09, p = .467), but was inversely related to internalizing in men (β = −0.44, p = .036). The direction of this association is opposite of that found in the correlational model, indicating a suppression effect: The variance in anger rumination that is shared with depressive rumination is positively associated with internalizing psychopathology, but the variance of anger rumination that is unique from depressive rumination is negatively associated with internalizing psychopathology.

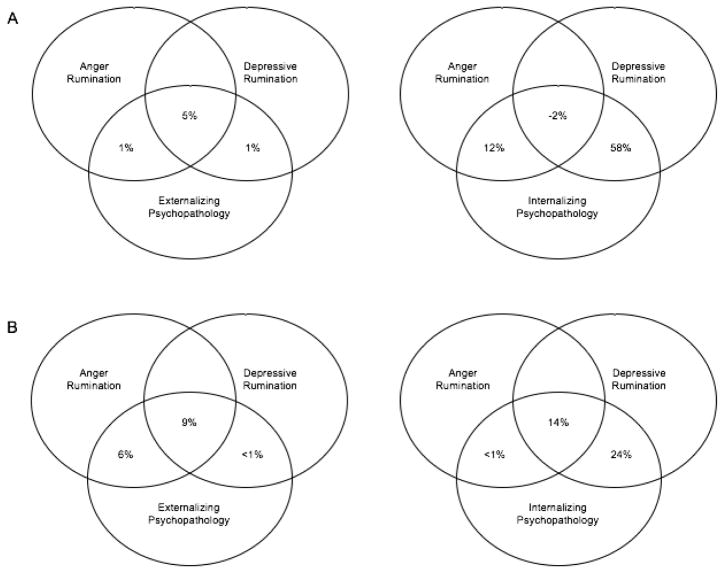

Given the moderate correlation between anger and depressive rumination, an important question is how much of the variance explained in psychopathology is attributable to variance common to both types of rumination, versus variance unique to each type. We used commonality analysis (Newton & Spurrell, 1967) to decompose the variances in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology explained by the common and unique variances in the two rumination factors (see Figure 3). Together, anger and depressive rumination explained 7% of the variance in externalizing psychopathology in men and 15% of the variance in externalizing psychopathology in women. The explained variance in externalizing was predominately accounted for by common variance in anger and depressive rumination; only 1% of the variance in externalizing psychopathology in men and 6% of the variance in externalizing in women was accounted for by variance unique to anger rumination.

Figure 3.

Venn diagrams depicting results from commonality analyses of rumination and psychopathology. Each diagram depicts the variance in internalizing or externalizing psychopathology that is explained by variance unique to anger or depressive rumination and variance shared by anger and depressive rumination (A) in men and (B) in women. Each circle represents the latent variables for anger rumination, depressive rumination, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Overlapping areas indicate variance that is explained by anger rumination, depressive rumination, or both (depiction of overlap is not to scale).

In contrast, 70% of the variance in internalizing psychopathology in men and 38% of the variance in internalizing psychopathology in women was explained by anger and depressive rumination (see Figure 3). Of the explained variance in internalizing psychopathology, 58% in men and 24% in women was accounted for by variance unique to depressive rumination. Of note was a negative variance (−2%) in internalizing psychopathology in men that was explained by both anger and depressive rumination. The negative variance in men does not indicate that less than 0% of the variance in internalizing was common variance explained by both forms of rumination (Amado, 1999), nor does it indicate the direction of the relationship between rumination and internalizing psychopathology. Rather, this negative value indicates the aforementioned suppressor effect between anger rumination, depressive rumination, and internalizing psychopathology.

Discussion

The present study examined anger and depressive rumination as cross-sectional correlates of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in young adults. Results indicated that although both anger and depressive rumination are associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, depressive rumination is more strongly associated with internalizing than is anger rumination. This result supports the clinical relevance of examining both ruminative thought processes and content. We elaborate on these points and implications of the associations between rumination and psychopathology, patterns of differential association, and sex differences in the following sections.

Anger and Depressive Rumination Are Associated With Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathology in Different Ways

Adding to the small body of literature examining rumination at the latent level, this study directly compared a one-versus two-factor model of anger and depressive rumination, and examined their independent associations with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Our results indicated that though anger and depressive rumination are common features of psychopathology, it is important to examine their independent associations with internalizing and externalizing, as these associations are nuanced and vary by ruminative subtype.

These results are consistent with previous research supporting a two-factor anger and depressive rumination model (e.g., Ciesla et al., 2011) as well as research examining the specificity of depressive rumination as a correlate of depressive symptoms (Peled & Moretti, 2010), and internalizing psychopathology (in adolescents; Garnefski, Kraaij, & van Etten, 2005; Hankin, 2009). These finding also build upon the anger rumination literature, which has predominately focused on anger rumination’s associations with anger (Rusting & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1998), aggression (Denson, Pedersen, Friese, Hahm, & Roberts, 2011), and symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., symptoms of borderline personality disorder; Baer & Sauer, 2011). Together, these results support the value of addressing both the process and emotional content (i.e., anger versus sadness) of rumination in clinical practice and research. As a common feature of psychopathology, ruminative thought processes should be a key target of new and existing clinical treatments (e.g., Watkins, 2009). As broad-band specific features of psychopathology, anger and depressive rumination may have differential clinical utility.

The present study further extended prior research on rumination and psychopathology by using commonality analysis to examine the proportion of variance explained in psychopathology by anger and depressive rumination. These results supported previous research documenting the importance of rumination, and particularly depressive rumination, in the initiation and maintenance of internalizing symptoms (e.g., Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). However, as rumination did not explain all of the variance in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, these results also indicate that there are additional processes and risk factors that substantially contribute to internalizing and externalizing psychopathology.

Sex Differences

Invariance tests of the measurement models suggested that men and women have distinct factor structures for both rumination and psychopathology. Thus, we noted, but did not formally test, qualitative sex differences: specifically, a significant association between anger rumination and externalizing in women and a suppression effect in the semipartial association between anger rumination and internalizing in men. The parameter estimates across men and women were similar, and in most cases, the standard errors suggested that the qualitative differences we observed were unlikely to reflect significant differences across sex.

Previous work has not examined the association between anger rumination and externalizing directly; however, a study by Ciesla and colleagues (2011) suggested that alcohol use contexts may differ significantly in men and women. Men may use social drinking as a method of distraction, whereas women may use it as a means of engaging in co-rumination (i.e., repetitive discussion of negative emotions and problems) that may ultimately heighten ruminative tendencies. Thus, one explanation for the association between unique variance in anger rumination and externalizing in women may be that drinking and other externalizing behaviors may serve to augment ruminative tendencies rather than distract from them.

However, it is also important to note that that internalizing and externalizing psychopathology were more closely related to each other in men than in women (r = .72 in men and .44 in women). There may be less independent association between anger rumination and externalizing psychopathology in men simply because there is less unique variance in externalizing psychopathology in men. Moreover, although the association between anger rumination and externalizing was not significant in men after controlling for depressive rumination, the direction of the association was similar across men and women. Hence, it is possible that there is an association in males that would require a larger sample to detect.

The suppression effect in the association between men’s anger rumination and internalizing when accounting for depressive rumination indicates that the variance of anger rumination that is unique from depressive rumination is negatively associated with internalizing psychopathology. However, this effect should be interpreted cautiously as the standard errors in Figure 2B indicate overlap in 95% confidence intervals for parameter estimates for men and women, though the association is significant in men but not in women.

Limitations and Future Directions

The use of latent variables extends research examining anger and depressive rumination, as it separates reliable variance in rumination from measurement error. Because latent variables predict multiple subscales or questionnaires, we were able to examine rumination in a less measure-dependent manner. However, although our depressive rumination latent variable included three subscales from two questionnaires, our anger rumination latent variable included four subscales from one questionnaire. Thus, a limitation of the present study is that the anger rumination subscales are likely to be more similar to each other than to the other questionnaires. This increased similarity between subscales may have contributed to the improvement in model fit of the two-factor rumination model. However, the fact that the rumination factors were differentially associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology suggests that these factors are distinguished by more than method variance. Future work could also include additional forms of rumination (e.g., positive rumination; Feldman et al., 2008) to develop a comprehensive understanding of the relations between subtypes of rumination and psychopathology.

The present study examined symptoms and diagnoses of psychopathology in a population sample of young adult twin pairs. Thus, the level of severity is lower than would be expected in a clinically recruited or inpatient sample. Previous work suggests that the structure of rumination may vary across non-clinically depressed and clinically depressed individuals (Whitmer & Gotlib, 2011), further pointing to the importance of examining the structure of rumination and the associations between rumination and psychopathology across levels of psychopathological severity.

There is also some speculation that twins experience unique prenatal and postnatal environments, which may limit the generalizability of results to nontwins. Research examining differences in psychopathology between twins and their nontwin relatives have typically found small differences (Kendler, Martin, Heath, & Eaves, 1995), indicating that the current results will likely generalize to the general population.

Additionally, although rumination is often conceptualized as a trait-like characteristic in adulthood (e.g., Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), little empirical work has examined the stability of rumination over the lifespan (e.g., Roach, Salt, & Segerstrom, 2010). Future work should extend and replicate these results in clinically relevant samples of varying ages to ensure the generalizability of these findings to the general population across the lifespan.

Although the present study supports and extends previous research documenting transdiagnostic associations between rumination and psychopathology, use of cross-sectional data and lifetime psychopathology symptom endorsement prevents the present study from elucidating the temporal associations between rumination and psychopathology. Some longitudinal research indicates that rumination may be a risk factor for psychopathology (e.g., McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), although it may also be a symptom or consequence of psychopathology (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007). Future work should strive to disentangle the temporal associations between rumination and psychopathology, as well as the role of other variables, such as stressful life events, poor social support, and impaired cognitive functioning, that may lead to both increased rumination and symptoms of psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants MH063207, MH016880, AG046938, and DA011015. Preliminary results from this study were presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Psychological Science (APS) in Chicago, IL in May 2016.

Footnotes

This model resulted in a warning that the latent variable covariance matrix in men was not positive definite. There were no out of bounds parameter estimates, so this warning was most likely as a result of multivariate collinearity: In males, rumination and externalizing psychopathology together explained all of the variance in internalizing psychopathology. Given that the values of this model were consistent with correlational models that included only internalizing or only externalizing psychopathology, we interpreted the parameters from this model.

The correlations (i.e., standardized covariances) were constrained to be equal by fixing the variances of the latent variables to one before constraining the covariances. Thus, the latent variable variances, rather than the first factor loading for each latent variable, were fixed to one to identify the model for these comparisons, which resulted in identical model fit for the full model.

As with the correlational model, the regression model resulted in a warning that the latent variable covariance matrix in men was not positive definite. Additionally, men’s residual correlation between internalizing and externalizing psychopathology was estimated at 1.15. We analyzed a model in which this residual correlation was constrained to one, and found that this constraint did not significantly hurt model fit, Δχ2(1) = 0.11, p = .737. Thus, we bounded the residual correlation in men so that it could not exceed one. The fit of the resulting model was very close to that for the unbounded model, and its parameters were consistent with regression models that included only internalizing or only externalizing psychopathology as dependent constructs.

References

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(10):974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Schweizer S. Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):217–237. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amado AJ. Partitioning predicted variance into constituent parts: A primer on regression commonality analysis. Annual meeting of the Southwest Educational Research Association; San Antonio, Texas. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Sauer SE. Relationships between depressive rumination, anger rumination, and borderline personality features. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment. 2011;2(2):142–150. doi: 10.1037/a0019478. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0019478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber L, Maltby J, Macaskill A. Angry memories and thoughts of revenge: The relationship between forgiveness and anger rumination. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39(2):253–262. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.01.006. [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Earleywine M, Jajodia A. Could mindfulness decrease anger, hostility, and aggression by decreasing rumination? Aggressive Behavior. 2010;36(1):28–44. doi: 10.1002/ab.20327. http://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calmes CA, Roberts JE. Repetitive thought and emotional distress: Rumination and worry as prospective predictors of depressive and anxious symptomatology. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2007;31(3):343–356. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9026-9. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Houts RM, Belsky DW, Goldman-Mellor SJ, Harrington H, Israel S, … Moffitt TE. The p Factor: One General Psychopathology Factor in the Structure of Psychiatric Disorders? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2(2):119–137. doi: 10.1177/2167702613497473. http://doi.org/10.1177/2167702613497473.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla JA, Dickson KS, Anderson NL, Neal DJ. Negative repetitive thought and college drinking: Angry rumination, depressive rumination, co-rumination, and worry. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(2):142–150. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9355-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The reliability of the CIDI-SAM: a comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction. 1989;84(7):801–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denson TF, Pedersen WC, Friese M, Hahm A, Roberts L. Understanding impulsive aggression: Angry rumination and reduced self-control capacity are mechanisms underlying the provocation-aggression relationship. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2011;37(6):850–862. doi: 10.1177/0146167211401420. http://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211401420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derks EM, Dolan CV, Boomsma DI. Effects of censoring on parameter estimates and power in genetic modeling. Twin Research: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2004;7(6):659–669. doi: 10.1375/1369052042663832. http://doi.org/10.1375/twin.7.6.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton NR, Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Balsis S, Skodol AE, Markon KE, … Hasin DS. An invariant dimensional liability model of gender differences in mental disorder prevalence: Evidence from a national sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):282–288. doi: 10.1037/a0024780. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. The impact of nonnormality on full information maximum-likelihood estimation for structural equation models with missing data. Psychological Methods. 2001;6(4):352–70. http://doi.org/10.1037//I082-989X.6.4.352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman GC, Joormann J, Johnson SL. Responses to positive affect: A self-report measure of rumination and dampening. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;32(4):507–525. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9083-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, van Etten M. Specificity of relations between adolescents’ cognitive emotion regulation strategies and Internalizing and Externalizing psychopathology. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28(5):619–631. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Cheung M, Irons C, McEwan K. An Exploration into Depression-Focused and Anger-Focused Rumination in Relation to Depression in a Student Population. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2005;33(3):273–283. http://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465804002048. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JW, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Rose RD, Waters AM, Sutton JM. Neuroticism as a common dimension in the internalizing disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40(7):1125–1136. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991449. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709991449.Neuroticism. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL. Rumination and depression in adolescence: Investigating symptom specificity in a multiwave prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;37(4):701–713. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359627. http://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359627.Rumination. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, Linden W. Anger response styles and blood pressure: at least don’t ruminate about it! Annals of Behavioral Medicine8: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(1):38–49. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_6. http://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2701_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DP, Rhee SH, Friedman NP, Corley RP, Munn-Chernoff MA, Hewitt JK, Whisman MA. A twin study examining rumination as a transdiagnostic correlate of psychopathology. Clinical Psychological Science. 2016 doi: 10.1177/2167702616638825. http://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616638825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson DP, Whisman MA. Gender differences in rumination: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55(4):367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2013.03.019. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Martin NG, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. Self-report psychiatric symptoms in twins and their nontwin relatives: Are twins different? American Journal of Medical Genetics - Neuropsychiatric Genetics. 1995;60(6):588–591. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320600622. http://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.1320600622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The Structure and Stability of Common Mental Disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. Comorbidity between and within childhood externalizing and internalizing disorders: Reflections and directions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31(3):285–291. doi: 10.1023/a:1023229529866. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023229529866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell JP. Anger rumination: An antecedent of athlete aggression? Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2004;5(3):279–289. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(03)00007-4. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;49(3):186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.08.021.Secreted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- Newton RG, Spurrell DJ. Examples of the Use of Elements for Clarifying Regression Analyses. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 1967;16(2):165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan SA, Roberts JE, Gotlib IH. Neuroticism and ruminative response style as predictors of change in depressive symptomatology. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1998;22(5):445–455. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018769531641. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109(3):504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Harrell ZA. Rumination, depression, and alcohol use: Tests of gender differences. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2002;16(4):391–404. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61(1):115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled M, Moretti MM. Rumination on anger and sadness in adolescence: fueling of fury and deepening of despair. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology8: The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53. 2007;36(1):66–75. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336569. http://doi.org/10.1080/15374410709336569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled M, Moretti MM. Ruminating on rumination: Are rumination on anger and sadness differentially related to aggression and depressed mood? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32(1):108–117. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9136-2. [Google Scholar]

- Reise SP, Widaman KF, Pugh RH. Confirmatory factor analysis and item response theory: Two approaches for exploring measurement invariance. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114(3):552–566. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. http://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea SA, Gross AA, Haberstick BC, Corley RP. Colorado twin registry. Twin Research and Human Genetics8: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2006;9(6):941–949. doi: 10.1375/183242706779462895. http://doi.org/10.1375/twin.9.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhea SA, Gross AA, Haberstick BC, Corley RP. Colorado twin registry - An update. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2013;18(9):1199–1216. doi: 10.1017/thg.2012.93. http://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.93.Colorado. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach AR, Salt CE, Segerstrom SC. Generalizability of repetitive thought: Examining stability in thought content and process. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2010;34(2):144–158. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-009-9232-3. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Compton WM, North CS, Rourke KM. Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the DSM-IV (DIS-IV) 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rusting CL, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Regulating responses to anger: effects of rumination and distraction on angry mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(3):790–803. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.790. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66(4):507–514. doi: 10.1007/s11336-009-9135-y. http://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(5):593–611. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby E, Anestis MD, Bender TW, Joiner TE. An exploration of the emotional cascade model in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;118(2):375–387. doi: 10.1037/a0015711. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0015711.An. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegle GJ, Moore PM, Thase ME. Rumination: One construct, many features in healthy individuals, depressed individuals, and individuals with lupus. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2004;28(5):645–668. http://doi.org/10.1023/B:COTR.0000045570.62733.9f. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder HR, Miyake A, Hankin BL. Advancing understanding of executive function impairments and psychopathology: Bridging the gap between clinical and cognitive approaches. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015;6(328) doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00328. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN. Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31(5):689–700. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen DK. The association between rumination and negative affect: A review. Cognition & Emotion. 2006;20(8):1216–1235. http://doi.org/10.1080/02699930500473533. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen DK, Mehlsen MY, Christensen S, Zachariae R. Rumination—relationship with negative mood and sleep quality. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(7):1293–1301. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00120-4. [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell PD, Campbell JD. Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76(2):284–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–259. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023910315561. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER. Depressive rumination: Investigating mechanisms to improve cognitive behavioural treatments. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(S1):8–14. doi: 10.1080/16506070902980695. http://doi.org/10.1080/16506070902980695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss B, Süsser K, Catron T. Common and specific features of childhood psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(1):118–127. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.118. http://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer A, Gotlib IH. Brooding and reflection reconsidered: A factor analytic examination of rumination in currently depressed, formerly depressed, and never depressed individuals. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35(2):99–107. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-011-9361-3. [Google Scholar]

- Whitmer AJ, Banich MT. Inhibition versus switching in different deficits forms of rumination. Psychological Science. 2007;18(6):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.