Short abstract

Two surveys of California public college students provide insight into the preliminary impact of the California Mental Health Services Authority's activities on college students' receipt of information about mental health issues and support services.

Keywords: California, Depression, Health Care Program Evaluation, Mental Health Treatment, Students, Suicide

Abstract

Two surveys of California public college students provide insight into the preliminary impact of the California Mental Health Services Authority's activities on college students' receipt of information about mental health issues and support services.

Mental health problems among college and university students in the United States are a significant public health issue. Indeed, mental disorders—clinically diagnosable mental health problems, which typically manifest themselves by young adulthood (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; Merikangas et al., 2010)—account for almost half of the disease burden for this age group in the United States (World Health Organization, 2008). Without treatment for their mental health problems, college students may face a difficult transition to adulthood and a range of long-lasting consequences: lower academic achievement and graduation rates (Breslau et al., 2008; King et al., 2006); higher rates of substance misuse (Angst, 1996; Weitzman, 2004) and alcohol abuse (Dawson et al., 2005); greater levels of social impairment and difficulties with close relationships (Druss et al., 2009), including an increased risk of divorce; and lower lifetime earning potential (Ettner, Frank, and Kessler, 1997; Kessler, Walters, and Forthofer, 1998; Kessler, Foster, et al., 1995; Smith and Smith, 2010).

With the rise in postsecondary enrollment in recent decades (Kena et al., 2016), colleges and universities have assumed an increasingly important role in addressing the mental health needs of students (Novotney, 2014). For many students, especially those who reside on campus, the college years are the only time when a single setting encompasses not only their primary activities—both career-related and social—but also their health and other support services. Given the unique nature of the college campus, faculty and staff, as well as campus organizations, are often well positioned to help identify students with potential mental health problems and to facilitate treatment (e.g., by identifying at-risk behaviors, educating students about mental health issues, and combating stigma associated with mental illness) by referring the students to appropriate mental health services.

With funding from California's Mental Health Services Act (Proposition 63), California counties began working collectively in 2011 under the California Mental Health Services Authority (CalMHSA) to develop and implement a series of statewide mental illness prevention and early intervention initiatives (PEIs), one of which was aimed at improving student mental health in the three California public higher-education systems: the ten-campus University of California (UC) system, the 23-campus California State University (CSU) system, and the 112-campus California Community College (CCC) system. Collectively, this work was known as the Statewide Student Mental Health Initiative (SMHI), which included a range of PEI activities, such as disseminating information and training students, staff, and faculty through empirically supported approaches to recognize and support individuals with mental health problems (Albright et al., 2013; Hadlacsky et al., 2014); conducting campus trainings and social media campaigns to reduce stigma around mental health issues and to motivate students, faculty, and staff to help others (Active Minds, undated); and creating programs to help students develop skills to better cope with stress and more quickly seek support when needed. Although the general goal of these activities was to enhance the campus climate with respect to mental health issues—as well as to help campuses more quickly reach and support students in need of mental health services before a problem becomes a crisis—the degree to which each campus implemented this multipronged effort, the focus of their efforts, and the methods by which they delivered information and PEI efforts varied from campus to campus based on the perceived needs of the student body, the existing campus supports, and the allotted funding.

As part of an ongoing evaluation of CalMHSA's student mental health initiative, the RAND Corporation conducted a campus-wide online survey of California college and university students in 2013 and 2014. Broadly, the survey was designed to increase our understanding of (1) the experiences and attitudes that students have on campus related to student mental health, (2) perceptions of how campuses are serving students' mental health needs, and (3) perceptions of the overall campus climate toward student mental health and well-being. In this study, we present findings from the UC, CSU, and CCC campuses that participated in both surveys; our specific aim was to determine the preliminary impact of CalMHSA's PEI activities on college students' receipt of information about mental health issues and support services and awareness of where to go for mental health support services.

Methods

RAND conducted the first survey of students on the UC, CSU, and CCC campuses during the spring and fall semesters of 2013 (survey 1, which occurred two years after the launch of SMHI) and the second survey during the spring and fall semesters of 2014 (survey 2, which occurred three years after the launch of SMHI). Although some respondents might have participated in both surveys, the goal was to survey a cross-section of the campus community at each time. For each survey, the UC and the CSU Offices of the President invited all of their systems' campuses to participate. The CCC Chancellor's Office invited a subset of the CCC campuses to participate (30 campuses with campus-based CalMHSA grants and 30 campuses without campus-based grants). Participating campuses distributed invitations to complete an online survey via email to students. Some campuses invited all students via email blasts, while other campuses invited a random sample of students. Individuals receiving invitations to participate also received an invitation to participate in a sweepstakes as an incentive. Reminder emails were sent once a week for three weeks to encourage participation in the survey. The study was approved by RAND's institutional review board (IRB) and the respective IRBs of the participating institutions, as needed.

Measures

Student Mental Health and Impairment

Students' current serious psychological distress was assessed via the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6), a reliable, valid six-item Likert measure (Kessler, Barker, et al., 2003; Kessler, Green, et al., 2010). The K6 assesses the frequency with which students experienced symptoms, such as hopelessness and worthlessness, during the prior 30 days. Using the standard cutoff criteria (Kessler, Barker, et al., 2003), students with a total score of 13 or higher were categorized as having current serious psychological distress.

Participants completed items modified from the National College Health Assessment (NCHA) II survey, assessing the extent to which a number of emotional or behavioral issues or stressors (i.e., anxiety, stress, depression, eating disorders, alcohol use, or death of a friend or family member) affected their academic functioning in the previous year (American College Health Association, 2010). Past-year mental health–related academic impairment was defined by the following: having dropped a course, received an incomplete, taken a leave of absence from school, or had similar “substantial academic disruption” resulting from the emotional or behavioral issue or stressor identified by the student.

Awareness of Where to Go for Campus Mental Health Services

Students were asked whether they knew where to go on campus if they needed mental health or other similar supportive services. Scores ranged from “not at all true” to “very much true” on a four-point Likert scale.

Receipt of Information About Student Mental Health Issues

Items adapted from the NCHA II 2010 spring survey (American College Health Association, 2010) assessed the extent to which students received information about various student mental health issues. Respondents indicated (yes or no) if they had received information from their colleges or universities on seven different topics (i.e., depression/anxiety, alcohol and other drug use, grief and loss, how to help others in distress, relationship difficulties, stress reduction, and suicide prevention).

Sample

A total of 39,265 students from participating schools in all three systems completed the first survey, and 19,946 students completed the second. These repeated cross-sectional surveys of students likely included some of the same students in the first and second surveys but did not follow specific individuals over time. Only students from campuses that participated in both surveys were included in the analytic sample, and information about the number of students invited to participate in each survey is unavailable. In addition, we excluded students from CCC campuses that did not receive campus-based grants from CalMHSA to enhance PEI activities for student mental health (n = 5,678). And we excluded students who identified their genders as “other” (e.g., transgender), because transgender individuals commonly experience unique mental health treatment issues distinct from lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer (LGBQ) and other students (e.g., for individuals who are considering gender affirmation surgery, diagnosis of gender dysphoria and counseling may be required) that would likely systematically influence the outcomes we are examining (Vance, Ehrensaft, and Rosenthal, 2014). After applying all exclusion criteria, a total of 28,982 students from the first survey and 13,968 students from the second across 26 campuses were included in the analytic sample. This included nine campuses from the UC system (n = 15,473 in 2013; n = 8,468 in 2014), five campuses from the CSU system (n = 3,267 in 2013; n = 1,041 in 2014), and 12 campuses from the CCC system (n = 10,242 in 2013; n = 4,459 in 2014).

Analytic Approach

The primary goal of this study was to determine the preliminary impact of CalMHSA's PEI activities on college students' awareness of where to find help for a mental health problem and on their receipt of information about mental health issues and support services. Specifically, we tested whether the percentage of students who reported receiving information on student mental health issues changed from 2013 to 2014 and also explored whether these changes in receiving information varied across higher-education systems (UC, CSU, and CCC) or between students who reported serious psychological distress or not. To test for these patterns of change, we used logistic regression models with appropriate controls.

To account for potential differences between student survey responders and each campus's student body, we weighted each campus's sample to match the distribution of the campus's student population using publicly available administrative data on gender, race and ethnicity, and enrollment status (full time versus part time). In addition, we weighted our sample for potential differences between survey 1 respondents and survey 2 respondents at the campus level. Using the weighted data, we conducted logistic regressions to examine potential changes in receipt of information about student mental health issues between 2013 and 2014. For each outcome, we controlled for relevant demographic and mental health–related characteristics. Specifically, we controlled for higher-education system, gender, race, student status (undergraduate versus graduate), LGBQ status, serious psychological distress, and academic impairment because of mental health issues. To help account for the fact that participating campuses might have already been engaging in efforts to push information out to students about health behaviors more generally, we controlled for student-reported receipt of information about Internet or computer game addiction and tobacco use, topics unlikely to be influenced by CalMHSA-supported activities. Finally, all analyses accounted for clustering of campuses within higher-education systems.

Results

Student Characteristics and Mental Health

Table 1 provides additional information about unweighted and weighted student characteristics and the higher-education systems in both surveys. Student respondents in both surveys were predominantly female, white, non-LGBQ, and undergraduates. Based on the weighted percentages, the prevalence of current serious psychological distress and mental health–related academic impairment were comparable in 2013 and 2014.

Table 1.

Student Characteristics from 2013 and 2014

| Characteristic | Survey 1 (2013) | Survey 2 (2014) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Unweighted Percentage | Weighted Percentage | n | Unweighted Percentage | Weighted Percentage | ||

| Total | 28,982 | — | — | 13,968 | — | — | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 18,475 | 64 | 55 | 9,016 | 65 | 55 | |

| Male | 10,294 | 36 | 45 | 4,803 | 35 | 45 | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 11,851 | 42 | 35 | 5,133 | 38 | 36 | |

| Latino | 7,154 | 25 | 31 | 3,524 | 26 | 29 | |

| Asian | 6,735 | 24 | 26 | 3,782 | 28 | 28 | |

| Black | 811 | 3 | 5 | 305 | 2 | 4 | |

| Other | 1,889 | 7 | 4 | 935 | 7 | 3 | |

| LGBQ | |||||||

| No | 26,323 | 91 | 90 | 12,477 | 89 | 91 | |

| Yes | 2,659 | 9 | 10 | 1,491 | 33 | 10 | |

| Student status | |||||||

| Undergraduate | 23,172 | 81 | 82 | 10,719 | 78 | 82 | |

| Graduate | 5,378 | 19 | 18 | 3,027 | 22 | 18 | |

| Psychological distress (SMI) | |||||||

| No | 23,088 | 81 | 79 | 10,541 | 77 | 79 | |

| Yes | 5,504 | 19 | 21 | 3,222 | 23 | 21 | |

| Academic impairment | |||||||

| No | 25,651 | 89 | 88 | 12,283 | 89 | 89 | |

| Yes | 3,128 | 11 | 12 | 1,557 | 11 | 11 | |

NOTE: SMI = serious mental illness.

Awareness of Where to Go for Mental Health Services on Campus

In 2013, 54.9 percent of student respondents said that they were aware of where to go on campus if they need mental health or similar supportive services. In 2014, there was a modest increase, to 56.6 percent, although not significantly different from 2013 (OR = 1.02, CI = 0.93 to 1.11).1 There were no significant differences between 2013 and 2014 by higher-education system (UC, CSU, and CCC) in student awareness of where to go on campus for mental health or similar supportive services.

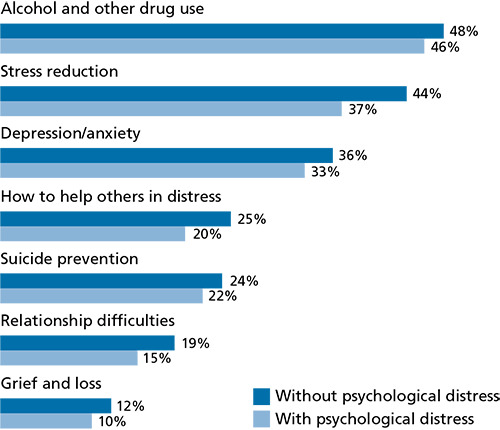

Receipt of Information About Student Mental Health Issues

Students were asked in both surveys whether they had received information about a variety of topics related to student mental health. In 2013, students reported that they received information about alcohol and other drug use most often (47 percent received information) and grief and loss least often (12 percent received information). Across topics, students were more likely to report receiving information about student mental health issues from online resources (e.g., Facebook, email, campus website, Student Health 101) (ranging from 59 percent for relationship difficulties to 72 percent for alcohol and other drug use) and in-person training or on-campus presentations (ranging from 58 percent for alcohol and other drug use to 68 percent for how to help others in distress) and less frequently from online trainings at their campuses (ranging from 21 percent for depression/anxiety to 46 percent for alcohol and other drug use). In 2013, statistically significantly (p < 0.01) fewer students with serious psychological distress reported receiving information about all mental health topics compared with students without serious psychological distress (Figure 1). Additionally, we found variation across campuses within each system in response to most of the questions regarding information about student mental health issues. For instance, in 2013, the percentage of students receiving online information about how to help others in distress ranged from 40 percent to 70 percent across UC campuses, from 54 percent to 68 percent across CSU campuses, and from 44 percent to 68 percent across CCC campuses.

Figure 1.

Fewer Students with Serious Psychological Distress Received Information About All Mental Health Topics Compared with Students Without Serious Psychological Distress

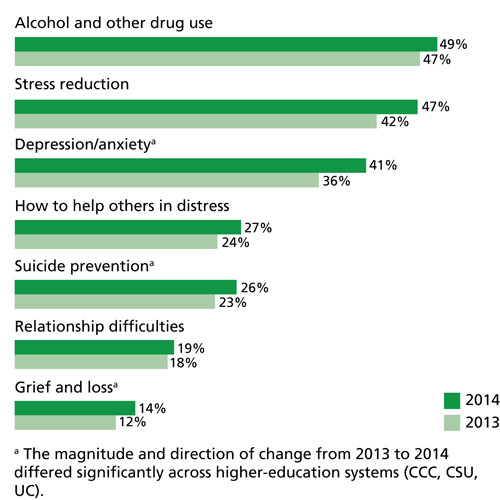

From 2013 to 2014 (Figure 2), the percentages of students receiving information about a variety of student mental health–related issues generally increased (ranging from a 1 percentage point increase for relationship difficulties to a 5 percentage point increase for stress reduction and depression/anxiety). Overall, students with and without serious psychological distress showed similar changes in receiving information about student mental health issues between 2013 and 2014. All three higher-education systems (UC, CSU, and CCC) showed comparable increases in the percentages of students receiving information about alcohol and drug use (a 2 percentage point increase), stress reduction (a 5 percentage point increase), how to help others in distress (a 3 percentage point increase), and relationship difficulties (a 1 percentage point increase).

Figure 2.

The Percentages of Students Receiving Information About Student Mental Health–Related Issues Generally Increased from 2013 to 2014

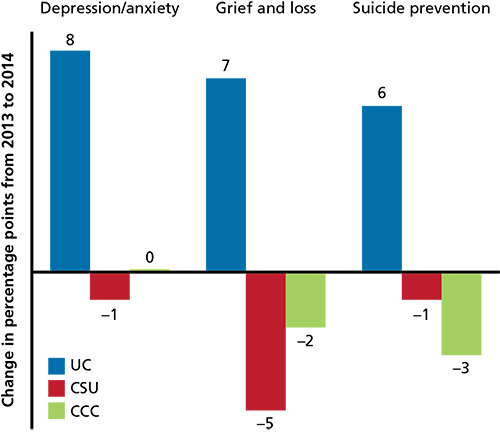

Although students' reports of receiving information were generally comparable across higher-education systems, we found some differences between higher-education systems in the magnitude and direction of change between 2013 and 2014 for depression/anxiety, suicide prevention, and grief and loss (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

UC Students Showed an Increase in Receiving Information on Mental Health Issues from 2013 to 2014, Compared with CSU and CCC Students Who Showed No Change or a Decrease Over Time

For depression/anxiety, students at UC campuses had a significant increase in receiving information from 2013 to 2014 (8 percentage points; p < 0.01). The CSU system showed a small and statistically insignificant decrease in the percentage of students receiving information from 2013 to 2014, which was statistically significantly different (p < 0.05) from the 8 percentage point increase shown for the UC system. The CCC system was not statistically significantly different from the UC system. For grief and loss, students on the UC campuses had a statistically insignificant 7 percentage point increase in receiving information from 2013 to 2014. The CSU system demonstrated a 5 percentage point decrease in the number of students receiving information from 2013 to 2014, which differed significantly (p < 0.05) from the 7 percentage point increase found for the UC system. Again, although the CCC system showed only a slight percentage point decrease (2 percentage points) in the number of students receiving information, the change was not statistically significantly different from the UC system. For suicide prevention, students on the UC campuses had a significant increase in receiving information from 2013 to 2014 (6 percentage points; p < 0.05). The change for both the CSU and the CCC systems differed significantly from the UC system. Specifically, the CSU system demonstrated a 1 percentage point decrease and CCC a 3 percentage point decrease between survey 2013 to 2014 in the number of students receiving information about suicide prevention, as compared with UC students who demonstrated a 6 percentage point increase in the number of students receiving information.

Discussion

To better understand how PEI activities can help influence college students' awareness of mental health resources and information about mental health issues, we examined survey data conducted at two points during the implementation of CalMHSA's student mental health initiative: in the spring and fall semesters of 2013, when efforts to enhance campus climates with respect to mental health were first under way, and again in the spring and fall of 2014, after a broad range of PEI trainings and social media campaigns had been in the field for approximately one year. Overall, we found that all three higher-education systems reached a large number of students on a variety of topics related to student mental health issues, particularly information about alcohol and other drug use, stress reduction, and depression/anxiety. However, although almost 50 percent of students said that they had received information about stress reduction and alcohol and other drug use, and approximately 40 percent said that they had received information about depression/anxiety, fewer than 30 percent of students reported exposure to the other four topics they were asked about, two of which—knowing how to help others in distress and suicide prevention—are CalMHSA priorities.

Our findings call attention to the need for more-efficient methods of disseminating information about mental health services and topics to students. Although we found little overall increase in students' exposure to mental health information from survey to survey, the UC system showed some significant increases in the percentages of students receiving information about depression/anxiety, grief and loss, and suicide prevention, as compared with the CSU and the CCC systems. When interpreting differences observed between systems, it is important to consider factors that may affect campuses' abilities to provide access to information and services for students with mental health needs. For instance, the systems may differ in terms of the percentage of students residing on campus, the extent to which faculty are interacting with students, and the extent to which services are available. Having much higher rates of resident students might have substantially enhanced the ability of the UC system to disseminate information to students, compared with the CSU and CCC systems. We are unable to assess the extent to which having a higher percentage of resident students influenced our findings, nor are we able to determine whether the level of reported exposure on a given campus is due to either the amount of information that students were exposed to or the effectiveness (or lack of effectiveness) of specific dissemination methods. Future work is needed to better understand to what extent strategies to disseminate information on college campuses with high rates of resident students are applicable to campuses with higher rates of commuting students and to what extent lessons learned from dissemination efforts on the UC campuses (e.g., modes of communication, timing and frequency of communication) are generalizable to campuses with fewer resident students.

Somewhat surprisingly, students with serious psychological distress reported receiving information about mental health issues at a lower rate, compared with students without serious psychological distress. Although CalMHSA's innovative and ambitious student mental health initiatives contained a range of PEI activities designed to improve student mental health and campus climates, it is unknown how much these activities connected more directly with students likely to benefit most from the information. To the extent that our finding is a reflection of students with serious psychological distress not receiving or paying attention to information about mental health issues, targeted strategies on campus to better connect with these students may be relevant. Research has shown that both educational and contact-based stigma-reduction interventions can result in positive changes in stigmatizing attitudes toward people with mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2012; Griffiths et al., 2014), as well as decreases in intentions to delay treatment and conceal mental health problems (Cerully et al., 2015; Wong et al., 2015). One approach to better reach individuals who are more likely to struggle with mental health problems could be partnering with campus organizations that may be more likely to address students with mental health needs, such as Active Minds; organizations targeting drinking or drug use on campus; or organizations focused on sexual and intimate-partner violence. Another approach could be to partner more heavily with campus organizations or settings that serve students who may have higher rates of mental health issues, such as academic support or counseling centers and student health centers. Together, these targeted efforts can complement ongoing universal campaigns that appear to be reaching the student population more broadly.

Furthermore, the availability of a formal network of on-campus mental health services was not a significant factor in students' awareness of where to find help for a mental health problem. We might expect that, because there are formal networks of on-campus mental health clinics on both CSU and UC campuses (unlike on CCC campuses), a larger percentage of UC and CSU students would say that they know where to go for mental health help, but this was not the case: The percentage of participating students who were aware of where to find mental health services—just over half in survey 1 (2013), with only a slight increase in survey 2 (2014)—was comparable across all three higher-education systems. Given that levels of awareness changed little after the first year of PEI activities, there is substantial room for improvement in efforts to increase awareness of and connect students to the mental health resources available to them on campus. Schools where students have access to formal on-campus mental health clinics seem particularly well positioned to be able to enhance this awareness.

In addition to these variations between the three systems, it is important to note that we also found substantial variation across campuses within each system in response to many of the questions. The UC, CSU, and CCC systems can use the information available to them not only to identify campuses facing the greatest challenges in disseminating information about student mental health issues to students but also to identify exemplary campuses that have been more successful than the majority have been in disseminating information about student mental health issues. These exemplary campuses may have developed processes or strategies that can be shared within and across systems. Furthermore, for campuses that have a sufficient sample and confidence in the generalizability of their findings, evaluating their results in comparison to these exemplary campuses can help identify priorities for policies and actions related to addressing student mental health issues on campus.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Not all campuses invited to participate did so. Our approach to surveying a convenience sample was similar to that of other large higher-education surveys (American College Health Association, undated; Boynton Health Service, 2012; Higher Education Research Institute, undated; Higher Education Research Institute, 2014), but given that each campus was responsible for inviting students to participate, we have no information about the numbers or characteristics of nonrespondents. We sought to mitigate effects of selection bias by weighting our sample to represent each campus's general student body, allowing us to adjust for selection bias associated with available demographic characteristics. Rates of self-reported current serious psychological distress (19 percent to 23 percent) were consistent with those reported by other studies in postsecondary educational settings (Hunt and Eisenberg, 2010), providing some reassurance that respondents were unlikely to have had higher rates of mental health problems than the general student body did. Still, we have no way to assess response bias—it is possible that respondents were more likely than nonrespondents to have been engaged with email or the Internet on an ongoing basis and, in turn, more likely to obtain information about student mental health issues disseminated via online sources. Moreover, because of our use of a convenience sample, we cannot assume that our findings generalize to all campus communities, nor can we assume they generalize to nonparticipating campuses. We also do not know how early CalMHSA activities on campuses might have influenced survey responses, although the majority of these activities occurred after the study period. Furthermore, we rely on student self-report and do not have objective information regarding student's exposure to information, nor whether the information being disseminated was supported by CalMHSA PEI activities. As a result, we are unable to determine whether students reporting that they did not see information being disseminated was a result of not receiving the information being disseminated (which might suggest the need for greater efforts to distribute information to all students), students not remembering having been exposed to information being disseminated (which might suggest the need for greater efforts to make materials more visually appealing or salient to students), or some other factor. We also have no information regarding the process by which information was disseminated in different systems and on different campus or how well that process was implemented, information that would be needed for any assessment of the effectiveness of different approaches. Any interpretation of findings should be made within these contexts and with consideration of other important differences that exist between the systems.

Conclusion

Educating college students about mental health issues may help combat the stigma associated with mental illness and facilitate help seeking and support for students experiencing mental health issues. Fostering awareness of where to go for a mental health problem may help connect students to the mental health services they need. Both of these are important stepping-stones to CalMHSA's goal of enhancing campus climates with respect to mental health issues and reducing unmet need for mental health treatment among California's college and university students. This study reveals the need for further evaluation of specific PEI activities to determine which can yield the most-meaningful changes in college students' awareness of where to find help for a mental health problem and in their access to information about mental health issues and support services. It also may be beneficial to focus dissemination efforts on a narrower range of mental health topics and to implement a consistent slate of PEI activities, not just across campuses within a system but across all three of California's public higher-education systems.

Note

The OR is the odds ratio. An odds ratio represents the likelihood that an outcome will occur given a particular exposure, compared with the likelihood of the outcome occurring in the absence of that exposure. The CI is the confidence interval. A confidence interval is a range of values representing a specified probability that the true value of a parameter lies within it.

The research described in this article was funded by the California Mental Health Services Authority (CalMHSA) and conducted by RAND Health.

References

- Active Minds. Send Silence Packing. web page, undated. As of April 28, 2017: http://www.activeminds.org/our-programming/send-silence-packing.

- Albright G., Goldman R., Shockley K., Spiegler J. Kognito's At-Risk Suite: Using Simulated Conversations with Virtual Humans to Build Mental Health Skills Among Educators, Staff, and Students: A Summary of Five Longtitudinal [sic] Studies. New York: Kognito; 2013. As of April 28, 2017: https://resources.kognito.com/uf/education_suite_survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. About ACHA-NCHA. web page, undated. As of April 28, 2017: www.acha-ncha.org/overview.html.

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association–National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Data Report Spring 2010. 2010. Linthicum, Md.

- Angst J. Comorbidity of Mood Disorders: A Longitudinal Prospective Study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;168(30):31–37. supplement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton Health Service. 2012 College Student Health Survey Report: Health and Health-Related Behaviors. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2012. As of April 28, 2017: http://www.bhs.umn.edu/surveys/survey-results/2012_Comprehensive_CSHSReport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J., Lane M., Sampson N., Kessler R. C. Mental Disorders and Subsequent Educational Attainment in a U.S. National Sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2008;42(9):708–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerully Jennifer L., Collins Rebecca L., Wong Eunice C., Roth Beth, Marks Joyce, Yu Jennifer. Effects of Stigma and Discrimination Reduction Programs Conducted Under the California Mental Health Services Authority: An Evaluation of Runyon Saltzman Einhorn, Inc., Documentary Screening Events. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2015. RR-1257-CMHSA. As of April 28, 2017: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1257.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P. W., Morris S. B., Michaels P. J., Rafacz J. D., Rüsch N. Challenging the Public Stigma of Mental Illness: A Meta-Analysis of Outcome Studies. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(10):963–973. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson D. A., Grant B. F., Stinson F. S., Chou P. S. Psychopathology Associated with Drinking and Alcohol Use Disorders in the College and General Adult Populations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss B. G., Hwang I., Petukhova M., Sampson N. A., Wang P. S., Kessler R. C. Impairment in Role Functioning in Mental and Chronic Medical Disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14(7):728–737. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettner S. L., Frank R. G., Kessler R. C. The Impact of Psychiatric Disorders on Labor Market Outcomes. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K. M., Carron-Arthur B., Parsons A., Reid R. Effectiveness of Programs for Reducing the Stigma Associated with Mental Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(2):161–175. doi: 10.1002/wps.20129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadlaczky G., Hokby S., Mkrtchian A., Carli V., Wasserman D. Mental Health First Aid Is an Effective Public Health Intervention for Improving Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviour: A Meta-Analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 2014;26(4):467–475. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.924910. August. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higher Education Research Institute. About the College Senior Survey. undated. As of April 28, 2017: www.heri.ucla.edu/cssoverview.php.

- Higher Education Research Institute. Findings from the 2014 College Senior Survey. Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles; 2014. As of April 28, 2017: www.heri.ucla.edu/briefs/CSS-2014-Brief.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J., Eisenberg D. Mental Health Problems and Help-Seeking Behavior Among College Students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kena G., Hussar W., McFarland J., de Brey C., Musu-Gillette L., Wang X., Ossolinski M. The Condition of Education 2016: Undergraduate Enrollment. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education; 2016. As of April 28, 2017: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cha.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler C. R., Barker P. R., Colpe L. J., Epstein J. F., Gfroerer J. C., Hiripi E., Howes M. J., Normand S. L., Manderscheid R. W., Walters E. E., Zaslavsky A. M. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(2):184–189. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Berglund P., Demler O., Jin R., Merikangas K. R., Walters E. E. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Foster C. L., Saunders W. B., Stang P. E. Social Consequences of Psychiatric Disorders, I: Educational Attainment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152(7):1026–1032. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Green J. G., Gruber M. J., Sampson N. A., Bromet E., Cuitan M. T. A. Furukawa, Gureje O., Hinkov H., Hu C. Y., Lara C., Lee S., Mneimneh Z., Myer L., Oakley-Browne M., Posada-Villa J., Sagar R., Viana M. C., Zaslavsky A. M. Screening for Serious Mental Illness in the General Population with the K6 Screening Scale: Results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2010;1;19:4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. Suppl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Walters E. E., Forthofer M. S. The Social Consequences of Psychiatric Disorders, III: Probability of Marital Stability. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(8):1092–1096. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.8.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K. M., Meehan B. T., Trim R. S., Chassin L. Marker or Mediator? The Effects of Adolescent Substance Use on Young Adult Educational Attainment. Addiction. 2006;101(12):1730–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas K. R., He J., Burstein M., Swanson S. A., Avenevoli S., Cui L., Benjet C., Georgiades K., Swendsen J. Lifetime Prevalence of Mental Disorders in U.S. Adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotney A. Students Under Pressure. Monitor on Psychology. 2014;45(8):37–41. As of April 28, 2017: http://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/09/cover-pressure.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. P., Smith G. C. Long-Term Economic Costs of Psychological Problems During Childhood. Social Science and Medicine. 2010;71(1):110–115. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance S. R., Ehrensaft D., Rosenthal S. M. Psychological and Medical Care of Gender Nonconforming Youth. Pediatrics. 2014;134(6):1184–1192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitzman E. R. Poor Mental Health, Depression, and Associations with Alcohol Consumption, Harm, and Abuse in a National Sample of Young Adults in College. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192(4):269–277. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120885.17362.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Eunice C., Collins Rebecca L., Cerully Jennifer, Roth Beth, Marks Joyce, Yu Jennifer. Effects of Stigma and Discrimination Reduction Trainings Conducted Under the California Mental Health Services Authority: An Evaluation of NAMI's Ending the Silence. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation; 2015. RR-1240-CMHSA. As of April 28, 2017: http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1240.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update Geneva. 2008.