Abstract

Background

Young adult solid organ transplant recipients who transfer from pediatric to adult care experience poor outcomes related to decreased adherence to the medical regimen. Our pilot trial for young adults who had heart transplant (HT) who transfer to adult care tests an intervention focused on increasing HT knowledge, self-management and self-advocacy skills, and enhancing support, as compared to usual care. We report baseline findings between groups regarding (1) patient-level outcomes and (2) components of the intervention.

Methods

From 3/14 – 9/16, 88 subjects enrolled and randomized to intervention (n=43) or usual care (n=45) at six pediatric HT centers. Patient self-report questionnaires and medical records data were collected at baseline, and 3 and 6 months after transfer. For this report, baseline findings (at enrollment and prior to transfer to adult care) were analyzed using chi square and t-tests. Level of significance was p< 0.05.

Results

Baseline demographics were similar in the intervention and usual care arms: age 21.3±3.2 vs 21.5±3.3 years and female 44% vs 49%, respectively. At baseline, there were no differences between intervention and usual care for use of tacrolimus (70% vs 62%); tacrolimus level (mean±SD=6.5±2.3 ng/ml vs 5.6±2.3 ng/ml); average of the within patient standard deviation of the baseline mean tacrolimus levels (1.6 vs 1.3); and adherence to the medical regimen (3.6±0.4 vs 3.5±0.5 [1=hardly ever to 4=all of the time]), respectively. At baseline, both groups had a modest amount of HT knowledge, were learning self-management and self-advocacy, and perceived they were adequately supported.

Conclusions

Baseline findings indicate that transitioning HT recipients lack essential knowledge about HT and have incomplete self-management and self-advocacy skills.

Keywords: heart transplant, adherence, behavior, knowledge, self-management

With improved long term survival after pediatric heart transplant (HT),1 more pediatric HT recipients are entering young adulthood and transferring to adult care than in the past. Young adulthood is a time of vulnerability, characterized by poor judgment, risk-taking behaviors, and emotional reactivity.2 Young adult solid organ transplant recipients who transfer from pediatric to adult care experience poor outcomes related to decreased adherence to the medical regimen,3 including unanticipated graft loss.4 Given that the health and well-being of chronically ill youth hinges on uninterrupted access to care,5 and the decline in adherence to medical regimens during and after transfer to an adult care program.3,4,6,7, “research on best practices and outcomes analysis is needed.”8

Our pilot trial, Pediatric Heart Transplantation: Transitioning to Adult Care (TRANSIT) addresses the potential for poor adherence during transfer from pediatric to adult care. TRANSIT tested an intervention, focused on enhancing adherence, that is based on “transition” (a complex set of beliefs, skills, and processes that facilitate the movement from pediatric to adult care)9,10 as opposed to simply “transfer of care” (movement to a new health care setting,).11 Specifically, the TRANSIT study tested the efficacy of an intervention focused on knowledge of HT, readiness to transition (i.e., self-management and self-advocacy), and social support, intended to improve outcomes for young adults, who underwent HT as children, during their transition to adult care. The purpose of this report is to compare baseline findings (at enrollment and prior to transfer to adult care) regarding (1) patient-level outcomes (i.e., calcineurin inhibitor [CNI] levels, adverse events, and self-report of adherence to the medical regimen), and (2) components of our adherence enhancing intervention (i.e., knowledge of HT, readiness to transition, and social support) in patients randomized to intervention versus usual care.

METHODS

Design and Theoretical Framework

Using a prospective, multi-center, randomized controlled trial design, we enrolled young adult HT recipients during their last pediatric visit who were randomized into one of two arms: (1) a transition program focusing on increasing HT-related knowledge, self-care, and self-advocacy skills, and enhancing social support and (2) usual care. Components of our transition program, as well as outcomes, were evaluated at baseline and 3 and 6 months after transfer to adult care.

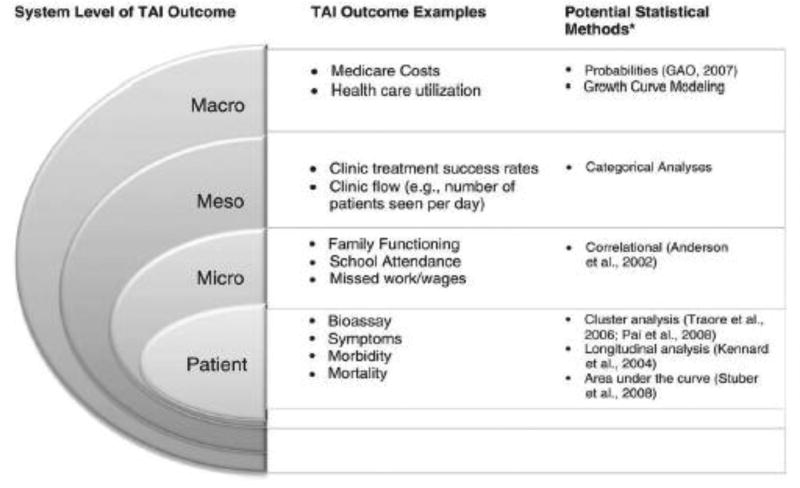

The Pai and Drotar Treatment Adherence Impact (TAI) model12 guided assessment of the impact of our intervention on outcomes. Outcomes that reflect treatment adherence belong to categories that are most proximal to the patient (e.g., patient-level) contrasted to those more distal (e.g., macro-level) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pai and Drotar Treatment Adherence Impact (TAI) model

Our intervention addressed two TAI model categories that reflect treatment adherence: (1) patient (bioassays [CNI blood levels], adverse events [e.g., episodes of acute rejection], and self-report of adherence to the medical regimen), and (2) meso (use of health care resources: rates of appointments for clinic and CNI blood draws and number of all-cause days re-hospitalized).

Setting and sample

Our study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at all participating sites. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study, prior to study participation. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02090257). Patients were recruited at six U.S. pediatric HT programs (in the east, mid-west, and west), which are well-established moderate to large pediatric HT centers approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid that participate in the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study.13 Enrolled participants transferred care to the partner adult programs.

Study inclusion criteria were: (1) received a HT at a Children’s Hospital and ready to transition to the adult program, determined by the pediatric transplant cardiologist; (2) ≥18 years; (3) able to speak, read at ≥ a fifth grade level, and write English; and (4) physically able to participate. Patients were excluded if they had a history of psychiatric hospitalization within the previous 3 months and could not potentially benefit from the intervention, developmental delay, or transition to a non-partner adult HT program.

Computer-based blocked randomization was used to allocate patients to a study arm within each clinical site. Between March 2014 and September 2016, 143 patients were screened and 88 (62%) were enrolled in our pilot trial. Patients completed baseline self-report instruments after providing informed consent and immediately before randomization.

Data Collection

Self-report and medical records data were collected at the last pediatric clinic visit (baseline) and 3 and 6 months after the first adult clinic visit. Self-report data were collected from the HT Knowledge Questionnaire, Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ), Social Support Index (SSI), and Assessment of Problems with the HT Regimen Questionnaire. The Heart Transplant Knowledge Questionnaire,14,15 developed by our research team, has 20 items (Appendix 1).14,15 Content (multiple choice and true / false) includes questions regarding knowledge of medications, appointment keeping, healthy lifestyle, benefits and risks of HT, and transition to adult care. Scores are calculated as total number of correct answers divided by the total number of questions. A higher score indicates having more HT knowledge. A score of ≥ 85% was determined to be a “passing score,” based on consensus of opinion among heart transplant clinicians on our research team, as we were unable to identify passing scores for heart transplant knowledge in the literature. Our fairly high passing score is based on concerns for patient safety (e.g., understanding the importance of taking immunosuppressants as prescribed, every day, and reporting symptoms promptly), wherein lack of knowledge and the potential for poor adherence to the medical regimen may be related to acute adverse events. Construct validity was supported by dividing patients in our pilot trial into two groups (≤high school versus >high school); patients with higher education answered more questions correctly, when compared to less educated patients.

The TRAQ,16 a 29-item survey, measures youth readiness to transition from pediatric to adult healthcare. It has two domains: skills for self-management (e.g., filling prescriptions) and skills for self-advocacy (e.g., reporting symptoms to the healthcare team). Responses are on a 6-point Likert scale. If patients indicated 1 = “not needed for my care”, they were not included in analyses for that item. Those items relevant to a patient’s care included the following response options: 2 = “no, I do not know how”, 3 = “no, I don’t know how but I want to learn”, 4 = “no, but I am learning to do this”, 5 = “yes, I have started doing this, and 6 = “yes, I always do this when I need to”. Thus, a higher score represents higher readiness to transfer. Psychometric support, including reliability and validity, is acceptable for this instrument.16

The SSI17 measures two types of social support (emotional and tangible) and overall support. Individuals in the support network and satisfaction (1 = very dissatisfied to 4 = very satisfied) are assessed for 15 support-related tasks (e.g., taking medications).17 Ratings are summed and averaged with higher scores indicating more satisfaction with support. The SSI has adequate psychometric support in the HT literature.17

The Patient Assessment of Problems with the HT Regimen18 measures actual adherence to 15 components of the HT medical regimen (e.g., immunosuppressants, diet, and clinic attendance).18 Patients indicate their level of adherence (1 = hardly ever and 4 = all of the time). Ratings are summed and averaged with higher scores indicating more adherence with the transplant regimen. Psychometric support is acceptable. Test-retest reliability is supported, as is content and concurrent validity.18

Baseline medical records data included collection of adverse events six months prior to the final pediatric clinic visit and CNI trough levels, as per routine blood draws (i.e., the last three levels collected in the pediatric setting).

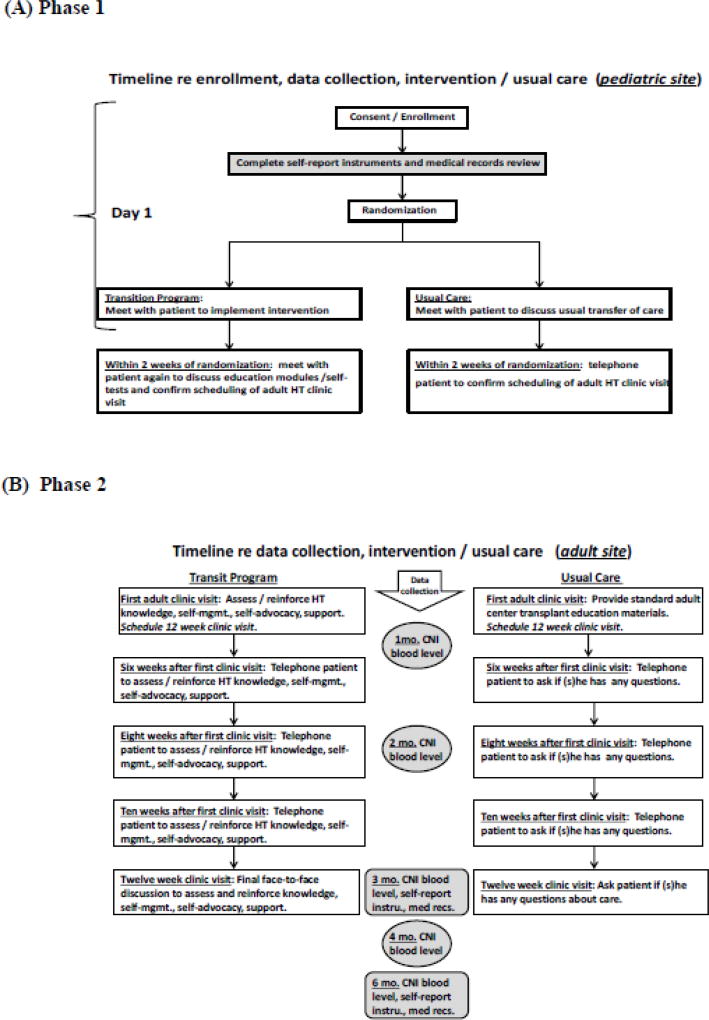

Intervention

Briefly, the intervention (i.e., transition program) had two phases (Figure 2). During Phase 1, at the pediatric site, patients randomized to the intervention arm reviewed four computer-based education modules and completed a self-test, followed by a discussion with the pediatric HT nurse coordinator. The HT modules and self-test focused on HT knowledge, self-management, self-advocacy, and support. The expected time to complete all modules and the self-test was 2 hours.

Figure 2.

Timeline for Delivery of Transition Program and Usual Care

Phase 2 began after transfer to the adult site, approximately 4–8 weeks after randomization, and included assessment, reinforcement, and tailoring of the module content by the adult HT coordinator at the first clinic visit. This discussion was followed by three telephone calls from the adult HT nurse coordinator, 6, 8, and 10 weeks after the 1st visit, to further assess and tailor discussions. The intervention concluded at the 3-month clinic visit with a final discussion of adequacy of self-management, self-advocacy, and support, including reinforcement of HT knowledge, as needed.

Usual care

The usual care group received a standard transfer of care (Figure 2). After randomization, patients met with the pediatric HT coordinator to discuss processes regarding transferring care. At the first adult clinic visit, 4–8 weeks later, the adult HT coordinator provided standard adult program information. Participants were contacted via telephone, by the adult transplant usual care nurse, 6, 8, and 10 weeks later to discuss concerns after transferring care.

Statistical Analyses

Continuously distributed variables were reported using the mean and standard deviation (SD). For immunosuppression levels, the median and first and third quartiles (Q1 and Q3) are reported. Comparisons between arms were based on the two-sample t-test with unequal variance or on Wilcoxon’s rank sum test. Variables with discrete distributions (binary or categorical) were summarized using counts and percentages, and comparisons by study arm were based on the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test.

For each study participant, we calculated the SD of their average immunosuppression blood levels (separately for participants on tacrolimus, cyclosporine, and sirolimus) and present the within study arm average of these SD estimates at baseline. Per the pediatric liver transplant literature, a SD of consecutive blood levels of tacrolimus above 2.5 indicates poor adherence.21–23 We also calculated the percentage of CNI levels within the target range (i.e., < 50% of CNI blood levels out of target range [below a target of 5 ng/dl for tacrolimus, and below 50 mg/dl for cyclosporine]).

RESULTS

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Of 88 enrolled patients, 43 randomized to intervention, and 45 to usual care. At baseline, there were no significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between arms (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). Patients in both arms were on average in their early 20s, and more than half of patients in both groups were male, white, single, and had at least some college education. The majority of patients in both groups were transplanted due to dilated cardiomyopathy or congenital heart disease and had 1–3 co-morbidities.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics by Study Arm

| Intervention N=43 |

Usual care N=45 |

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean± SD) | 21.3 ± 3.2 | 21.5 ± 3.3 | 0.75 | ||

| Gender (n/%) | 0.66 | ||||

| Male | 24 | (56%) | 23 | (51%) | |

| Female | 19 | (44%) | 22 | (49%) | |

| Caucasian Race (n/%) | 0.51 | ||||

| No | 8 | (19%) | 11 | (24%) | |

| Yes | 35 | (81%) | 34 | (76%) | |

| Education (n/%) | 0.75 | ||||

| Some high school (9–12) | 4 | (9%) | 6 | (13%) | |

| High school graduate | 13 | (30%) | 8 | (18%) | |

| > High school education | 26 | (60%) | 31 | (68%) | |

| Technical school | 1 | (2%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Some college | 21 | (49%) | 25 | (56%) | |

| Associate degree | 1 | (2%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| Bachelor degree | 3 | (7%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| Post college Graduate degree | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Current Marital Status (n/%) | 0.10 | ||||

| Married | 1 | (2%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| Partner | 4 | (9%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Single | 38 | (88%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| Working for income (n/%) | 0.09 | ||||

| No | 26 | (60%) | 19 | (42%) | |

| Yes | 17 | (40%) | 26 | (58%) | |

SD = standard deviation

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics by Study Arm

| *Clinical characteristics of enrollees | Intervention N=43 |

Usual care N=45 |

p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure diagnosis (n/%) | 0.28 | ||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 21 | (48.8%) | 20 | (44.4%) | |

| Congenital heart disease | 20 | (46.5%) | 25 | (55.6%) | |

| Myocarditis | 2 | (4.7%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Congenital heart disease (n/%) | N=20 | N=25 | 0.27 | ||

| CHD-Complete AV Septal Defect | 1 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| CHD-Congenitally Corrected transposition | 1 | (5%) | 1 | (4%) | |

| CHD-Ebsteins Anomaly | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (4%) | |

| CHD-Hypoplastic Left Heart | 6 | (30%) | 14 | (56%) | |

| CHD-Left Heart Valvular/Structural Hypoplasia | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (4%) | |

| CHD-Pulmonary Atresia with IVS | 2 | (10%) | 1 | (4%) | |

| CHD-Other Single Ventricle | 0 | (0%) | 2 | (8%) | |

| CHD-TOF/DORV/RVOTO | 4 | (20%) | 1 | (4%) | |

| CHD-Transposition of the Great Arteries with Arterial Switch | (5%) | 0 | (0%) | ||

| CHD-Other | 5 | (25%) | 4 | (16%) | |

| Medical history: # co-morbidities (n/%) | 0.75 | ||||

| 0 | 9 | (21%) | 9 | (20%) | |

| 1 | 14 | (33%) | 12 | (27%) | |

| 2 | 8 | (19%) | 8 | (18%) | |

| 3 | 7 | (16%) | 9 | (20%) | |

| 4 | 4 | (9%) | 5 | (11%) | |

| 5 | 1 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| 6 | 0 | (0%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| Surgical history: prior open cardiac surgeries (n/%) | 0.53 | ||||

| 0 | 26 | (60%) | 32 | (71%) | |

| 1 | 10 | (23%) | 8 | (18%) | |

| 2 | 3 | (7%) | 3 | (7%) | |

| 3 | 1 | (2%) | 2 | (4%) | |

| 4 | 1 | (2%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| 5 | 2 | (5%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Surgical history: prior closed cardiac surgeries (n/%) | 0.08 | ||||

| 0 | 31 | (72%) | 39 | (87%) | |

| 1 | 8 | (19%) | 6 | (13%) | |

| 2 | 4 | (9%) | 0 | (0%) | |

| Surgical history: heart re-transplant (n/%) | 0.13 | ||||

| No | 33 | (77%) | 40 | (89%) | |

| Yes | 10 | (23%) | 5 | (11%) | |

| Immunosuppression (n/%) | |||||

| % tacrolimus (Prograf and Hecoria) | 30 | (70%) | 28 | (62%) | 0.46 |

| % cyclosporine | 9 | (21%) | 10 | (22%) | 0.88 |

| % mycophenolate (Cellcept and Myfortic) | 26 | (60%) | 23 | (51%) | 0.38 |

| % azathioprine | 3 | (7%) | 5 | (11%) | 0.50 |

| % sirolimus | 20 | (47%) | 22 | (49%) | 0.82 |

| Episodes of acute rejection (6 mos. prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | 0.23 | ||||

| 0 | 39 | (91%) | 43 | (98%) | |

| 1 | 4 | (9%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| 2 | 0 | (0%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Episodes of major infection (6 mos. prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | 0.56 | ||||

| 0 | 39 | (91%) | 43 | (96%) | |

| 1 | 3 | (7%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| 2 | 1 | (2%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| Re-hospitalizations (6 mos. prior to final pediatric clinic visit) (n/%) | 0.62 | ||||

| 0 | 33 | (77%) | 38 | (84%) | |

| 1 | 7 | (16%) | 4 | (9%) | |

| 2 | 2 | (5%) | 1 | (2%) | |

| 3 | 1 | (2%) | 2 | (4%) | |

CHD=congenital heart disease, IVS=intact ventricular septum, TOF=Tetralogy of Fallot, DORV=double outlet right ventricle, RVOTO=right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Components of the Adherence Enhancing Intervention

Self-report assessments were similar between groups at baseline (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Self-report Questionnaires

| A Baseline Heart Transplant Knowledge Questionnaire | ||||||

| Variable | N | Intervention (N=43) | Usual care (N=45) | P-value | ||

| Total (% correct) | 88 | 73.5 | ± 13.0 | 72.7 | ± 10.7 | 0.75 |

| HTKQ Medications (% correct) | 88 | 72.4 | ± 16.3 | 71.1 | ± 12.2 | 0.68 |

| HTKQ Health Status (% correct) | 88 | 68.2 | ± 29.1 | 67.4 | ± 24.1 | 0.89 |

| HTKQ Lifestyle (% correct) | 88 | 75.6 | ± 14.9 | 76.7 | ± 14.5 | 0.73 |

| HTKQ Follow-up Care (% correct) | 88 | 72.9 | ± 25.5 | 73.3 | ± 23.1 | 0.93 |

| B Baseline Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire | ||||||

| Variable | N | Intervention (N=43) | Usual care (N=45) | P-value | ||

| TRAQ Skills for chronic conditions self-management (Mean±SD) | 88 | 4.2 | ± 0.9 | 4.1 | ± 0.9 | 0.59 |

| TRAQ Skills for self-advocacy and health care utilization (Mean±SD) | 88 | 4.4 | ± 0.7 | 4.4 | ± 0.5 | 0.76 |

| C Baseline Social Support Index | ||||||

| Variable | N | Intervention (N=43) | Usual care (N=45) | P-value | ||

| SSI score (Mean±SD) | 88 | 3.8 | ± 0.4 | 3.7 | ± 0.5 | 0.46 |

| SSI Tangible Support score (Mean±SD) | 88 | 3.8 | ± 0.4 | 3.8 | ± 0.5 | 0.56 |

| SSI Emotional Support score (Mean±SD) | 88 | 3.8 | ± 0.4 | 3.7 | ± 0.6 | 0.46 |

HTKQ=Heart Transplant Knowledge Questionnaire, TRAQ=Transition Readiness Questionnaire, SD=standard deviation, SSI=Social Support Index

TRAQ scoring: 6=yes, I always do this when I need to; 5=yes, I have started doing this; 4=no, but I am learning to do this; 3=no, I don’t know how but I want to learn; 2=no, I do not know how; 1=not needed for my care. A higher score represents higher readiness to transfer.

SSI scoring: 4=very satisfied; 3=fairly satisfied; 2=somewhat dissatisfied; 1=very dissatisfied. A higher score represents more satisfaction.

HT Knowledge

Patients in both arms had similar total HT knowledge scores (mean percent of correct answers: intervention = 73.5±13.0% versus usual care = 72.7±10.7%, p=0.75) (Table 3A). Mean percent of correct subscale knowledge scores were also similar (intervention subscale range=68–76% and usual care subscale range=67–77%). Mean scores were lowest for the health status subscale for both groups.

The number of patients who achieved a total passing score of 85% correct responses was low in both groups, and there were no significant between group differences in number of patients (intervention = 11/43 [26%] versus usual care = 8/45 [18%], p=0.37). The mean percent of correct subscale knowledge scores were also similar for the 11 intervention patients and 8 usual care patients who achieved a passing score (intervention subscale range = 80% – 91% and usual care subscale range = 78% – 96%).

Self-management and self-advocacy

Mean group scores for the two subscales of the TRAQ demonstrated that participants in both arms were similarly learning to implement self-management activities or starting to implement health care activities (i.e., scores were between 4 = “no, but I am learning to do this” and 5 = “yes, I have started doing this”: (1) skills for self-management (intervention = 4.2±0.9 versus usual care = 4.1±0.9, p=0.59) and (2) skills for self-advocacy and health care utilization (intervention = 4.4±0.7 versus usual care = 4.4±0.5, p=0.76) (Table 3B).

Support

Patients in both groups were satisfied with support (Table 3C). Patients reported being quite satisfied overall (total mean scores: intervention = 3.8±0.4 versus usual care = 3.7±0.5, p=0.46) and quite satisfied regarding the two subscales, tangible and emotional support.

Patient-level Outcomes

Immunosuppression

Six months prior to the final pediatric clinic visit, the majority of patients in both groups were receiving tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil for immunosuppression (Table 4). Mean tacrolimus blood levels at baseline were similar between groups (intervention [n=30] = 6.5±2.3 versus usual care [n=28] = 5.6±2.3, p=0.36). The average of the within patient SD of the baseline mean tacrolimus level was comparable between study arms (1.6 intervention vs 1.3 usual care, p=0.12) and <2.5, suggesting adequacy of adherence to taking tacrolimus. For the small subset of patients receiving cyclosporine as their CNI, instead of tacrolimus, baseline blood levels were also similar between groups (intervention [n=9] = 138.5±42.6 versus usual care [n=10] = 112±35.0, p=0.16). Furthermore, the majority of patients in both groups had CNI trough levels (i.e., tacrolimus and cyclosporine levels) within each site’s specified target range, individualized by patient. Lastly, some patients were on sirolimus, the majority of whom were at one institution, reflecting institutional practice. The difference in average sirolimus within participant SDs was statistically significant (1.8 intervention vs 1.9 usual care); however, it does not appear to be a clinically important difference (i.e., the difference in the average SDs was only 0.1).

Table 4.

Baseline Immunosuppression Blood Levels

| Intervention Arm N=43 |

Usual Care Arm N=45 |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tacrolimus | n=30 | n=28 | |

| # of blood draws per patient | 1.0 | ||

| 3 | 30 (100%) | 28 (100%) | |

| blood levels within target range (%) | 68.8% | 71.7% | 0.51 |

| blood levels (mean ± SD) | 6.5±2.3 | 5.6±2.3 | 0.36 |

| blood levels (median [Q1, Q3]) | 6.2 (4.8, 8.1) | 5.3 (4.2, 7.2) | 0.12 |

| blood levels average of within-participant standard deviation values | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.12 |

| Cyclosporine | n=9 | n=10 | |

| # of blood draws per patient | 1.0 | ||

| 3 | 9 (100%) | 10 (100%) | |

| blood levels within target range (%) | 74.1% | 70.0% | 0.80 |

| blood levels (mean ± SD) | 138.5±42.6 | 112±35.0 | 0.16 |

| blood levels (median [Q1, Q3]) | 147 (108.5, 168.3) | 104 (86.6, 138.6) | 0.51 |

| blood levels average of within-participant standard deviation values | 22.4 | 37.0 | 0.26 |

| Sirolimus | n=21 | n=21 | |

| # of blood draws per patient | 1.0 | ||

| 3 | 21 (100%) | 21 (100%) | |

| blood levels within target range (%) | 71.4% | 66.7% | 0.63 |

| blood levels (mean ± SD) | 5.8±3.0 | 5.7±2.3 | 0.97 |

| blood levels (median [Q1, Q3]) | 5.1 (3.7, 6.2) | 5.8 (4.0, 6.4) | 0.13 |

| blood levels average of within-participant standard deviation values | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.03 |

Adverse events

The vast majority of patients in both groups similarly had no acute rejection, major infection, or re-hospitalization within six months prior to the final pediatric visit (Table 2).

Adherence

Patients in both arms reported being quite adherent to their self-care regimen at baseline per mean scores for overall adherence (intervention = 3.6±0.4 versus usual care = 3.5±0.5, p=0.20) (Table 5). Self-reported adherence to components of the health care regimen were similar between groups, but variable. Patients in both groups reported being more adherent with taking medications and keeping appointments (range of average scores for both groups = 3.6–3.8) and less adherent with lifestyle modifications and health monitoring (range of average scores for both groups = 2.6–3.1).

Table 5.

Baseline Assessment of Problems with the Heart Transplant Regimen

| Baseline Assessment of Problems with the Heart Transplant Regimen* | ||||||

| Variable | N | Intervention (N=43) | Usual care (N=45) | P-value | ||

| Total score (Mean±SD) | 88 | 3.6 | ± 0.4 | 3.5 | ± 0.5 | 0.20 |

| Medications score (Mean±SD) | 88 | 3.8 | ± 0.4 | 3.7 | ± 0.5 | 0.74 |

| Lifestyle Score (Mean±SD) | 51 | 3.1 | ± 1.0 | 2.8 | ± 1.0 | 0.28 |

| Health Monitoring Score (Mean±SD) | 56 | 2.9 | ± 1.0 | 2.6 | ± 1.1 | 0.32 |

| Baseline Assessment of Problems with the Heart Transplant Regimen* | ||||||

| Variable | N | Intervention (N=43) | Usual care (N=45) | P-value | ||

| Appointment Keeping Score (Mean±SD) | 72 | 3.8 | ± 0.4 | 3.6 | ± 0.8 | 0.19 |

SD=standard deviation

Scoring: 4=all of the time; 3=most of the time; 2=some of the time; 1=hardly ever. A higher score indicates more adherence with the transplant regimen.

DISCUSSION

At baseline, participants in both study arms had inadequate HT knowledge and self-management and self-advocacy skills. Of concern, young adult HT recipients in both arms answered, on average, less than 75% of HT knowledge questions correctly, and less than 30% of patients in both groups had passing scores (i.e., total score ≥ 85%). Incorrect answers were identified in all areas assessed, including medications, health status, lifestyle, and follow-up care. The lowest subscale score was health status, which reflects knowledge about monitoring one’s health status and recognizing signs and symptoms that require contacting the HT team. Uzark et al.24 recently evaluated transition readiness, which included knowledge deficits among 13–25 year olds with congenital heart disease (96%) or post HT (4%) and similar to our findings, reported an average perceived knowledge deficit score of 25.7% among patients of all ages. Furthermore, these investigators also identified symptom reporting as being among the most common perceived knowledge deficits.24 Other researchers have also reported poor disease and treatment knowledge among adolescents and young adults with congenital heart disease.25,26 According to best practice guidelines, a transition curriculum (e.g., symptoms, labs/tests, treatments, and lifestyle issues) is important in a successful transition program.8,27

Not surprisingly, at baseline, patients in both groups were still developing skills regarding HT self-management and self-advocacy / health care utilization. Incomplete skill development (e.g., not knowing how to perform skills) has been demonstrated in other younger (< 18 years) cardiac populations.24, 26, 28 Notably, in the pediatric HT setting, patient care is typically coordinated by parents. Our baseline findings reinforce inclusion of self-management in a transition program, which is supported in the pediatric and adolescent solid organ transplantation literature.21,29 Furthermore, two meta-analyses demonstrated that multi-component interventions, including education and behavioral skills were most successful in promoting adherence to chronic care regimens.30, 31

We also found that at baseline, young adult HT recipients in both groups were satisfied with support from family and friends. Inclusion of social support as a component of our intervention is supported by studies of solid organ transplant recipients wherein support was found to be related to positive outcomes.9,32 However, young adults transitioning to adult HT programs need to have parents as support persons, rather than as care coordinators, which we address in our intervention. Bell et al.8 and Sable et al.27 also discuss the importance of shifting the parental role from care coordination to support during transition.

Regarding baseline patient-level outcomes, patients in both groups received similar CNIs and had similar CNI blood levels, which were within target range, and similar average within patient SD variation, further reflecting adherence with taking immunosuppression. Six months prior to the last pediatric clinic visit, patients in both groups similarly had low frequencies of adverse events, including episodes of acute rejection. Patients in both groups also reported being fairly adherent to the medical regimen, although there were differences by regimen component. Our focus on self-reported adherence to the medical regimen as an outcome is supported by the literature, which demonstrates that poor adherence during the transition to adult healthcare may be associated with poor medical outcomes, including increased risk of graft failure and death.8,33 Reports of pediatric kidney and liver transplant recipients transitioned to adult care centers have noted worsening adherence and graft loss within the first year after transition.3,4 Variation in self-reported adherence by component, found in both groups, at baseline, is not surprising. Better adherence to taking medications and worse adherence to lifestyle recommendations has been reported in the literature.18

CONCLUSIONS

Our baseline findings indicate that pediatric HT recipients who are required to navigate the transition to adult care programs for continuity of care, lack essential knowledge about HT and have incomplete self-management and self-advocacy skills. Our longitudinal analyses will inform whether an intervention, focused on adherence, improves outcomes, as compared to usual care, early after transfer to adult care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), grant number R34 HL111492. (PIs E Pahl and K Grady)

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving Human Participants: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (institutional review boards [IRBs]) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. IRB approval was received from all participating institutions, prior to study initiation.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dipchand AI, Rossano JW, Edwards LB, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Eighteenth Official Pediatric Heart Transplantation Report--2015; Focus Theme: Early Graft Failure. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015 Oct;34(10):1233–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell LE, Sawyer SM. Transition of care to adult services for pediatric solid-organ transplant recipients. Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 2010 Apr;57(2):593–610. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.01.007. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annunziato RA, Emre S, Shneider B, Barton C, Dugan CA, Shemesh E. Adherence and medical outcomes in pediatric liver transplant recipients who transition to adult services. Pediatr. Transplant. 2007 Sep;11(6):608–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson AR. Non-compliance and transfer from paediatric to adult transplant unit. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2000 Jun;14(6):469–472. doi: 10.1007/s004670050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotstein DS, Ghandour R, Cash A, McGuire E, Strickland B, Newacheck P. Planning for health care transitions: results from the 2005–2006 National Survey of Children With Special Health Care Needs. Pediatrics. 2009 Jan;123(1):e145–152. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid GJ, Irvine MJ, McCrindle BW, et al. Prevalence and correlates of successful transfer from pediatric to adult health care among a cohort of young adults with complex congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2004 Mar;113(3 Pt 1):e197–205. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.3.e197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kipps S, Bahu T, Ong K, et al. Current methods of transfer of young people with Type 1 diabetes to adult services. Diabet. Med. 2002 Aug;19(8):649–654. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell LE, Bartosh SM, Davis CL, et al. Adolescent Transition to Adult Care in Solid Organ Transplantation: a consensus conference report. Am. J. Transplant. 2008 Nov;8(11):2230–2242. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fredericks EM. Nonadherence and the transition to adulthood. Liver Transpl. 2009 Nov;15(Suppl 2):S63–69. doi: 10.1002/lt.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawyer SM, Blair S, Bowes G. Chronic illness in adolescents: transfer or transition to adult services? J. Paediatr. Child Health. 1997 Apr;33(2):88–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1997.tb01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Callahan ST, Winitzer RF, Keenan P. Transition from pediatric to adult-oriented health care: a challenge for patients with chronic disease. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2001 Aug;13(4):310–316. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai AL, Drotar D. Treatment adherence impact: the systematic assessment and quantification of the impact of treatment adherence on pediatric medical and psychological outcomes. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010 May;35(4):383–393. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dipchand AI, Kirk R, Mahle WT, et al. Ten yr of pediatric heart transplantation: a report from the Pediatric Heart Transplant Study. Pediatr. Transplant. 2013 Mar;17(2):99–111. doi: 10.1111/petr.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A Patient Handbook. Chicago, IL: Northwestern Memorial Hospital; 2005. Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute, Heart Transplantation. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heart Transplatation Education Handbook. Chicago, IL: Children's Memorial Hospital; 2010. Children's Memorial Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011 Mar;36(2):160–171. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C, et al. Predictors of quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure awaiting transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 1995 Jan-Feb;14(1 Pt 1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grady KL, Jalowiec A, White-Williams C. Patient compliance at one year and two years after heart transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 1998 Apr;17(4):383–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lennon CB, Burdick H. The Lexile Framework as an approach for reading measurement and success. MetaMetrics, Inc; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching Patients with Low Literacy Skills. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Paperback; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Shneider BL, et al. Improving adherence to medications in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 2008 May;12(3):316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shemesh E, Shneider BL, Savitzky JK, et al. Medication adherence in pediatric and adolescent liver transplant recipients. Pediatrics. 2004 Apr;113(4):825–832. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.4.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stuber ML, Shemesh E, Seacord D, Washington J, 3rd, Hellemann G, McDiarmid S. Evaluating non-adherence to immunosuppressant medications in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Pediatr. Transplant. 2008 May;12(3):284–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Uzark K, Smith C, Donohue J, et al. Assessment of Transition Readiness in Adolescents and Young Adults with Heart Disease. J. Pediatr. 2015 Dec;167(6):1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moons P, De Volder E, Budts W, et al. What do adult patients with congenital heart disease know about their disease, treatment, and prevention of complications? A call for structured patient education. Heart. 2001 Jul;86(1):74–80. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.1.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mackie AS, Islam S, Magill-Evans J, et al. Healthcare transition for youth with heart disease: a clinical trial. Heart. 2014 Jul;100(14):1113–1118. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sable C, Foster E, Uzark K, et al. Best practices in managing transition to adulthood for adolescents with congenital heart disease: the transition process and medical and psychosocial issues: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Apr 05;123(13):1454–1485. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182107c56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart KT, Chahal N, Kovacs AH, et al. Readiness for transition to adult health care for young adolescents with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:778–786. doi: 10.1007/s00246-017-1580-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zelikovsky N, Schast AP, Palmer J, Meyers KE. Perceived barriers to adherence among adolescent renal transplant candidates. Pediatr. Transplant. 2008 May;12(3):300–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graves MM, Roberts MC, Rapoff M, Boyer A. The efficacy of adherence interventions for chronically ill children: a meta-analytic review. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010 May;35(4):368–382. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2008 Jul;33(6):590–611. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bers MU, Beals LM, Chau C, et al. Use of a virtual community as a psychosocial support system in pediatric transplantation. Pediatr. Transplant. 2010 Mar;14(2):261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McBride ME, Foushee MT, Brown RN, Ewald GA, Canter CE. Outcomes of pediatric heart transplant recipients transitioned to adult care: an exploratory study. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2010 Nov;29(11):1309–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.