Abstract

Background

Exception from informed consent imposes community consultation and public disclosure requirements on clinical investigation in critically ill and injured patients. In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) instructed sponsors to submit publically disclosed information to the FDA Docket, but to date there has been no comprehensive analysis of available data. We summarized the community consultation and public disclosure practices of exception from informed consent trials published on the FDA docket in order to better understand the breadth of common practices that exists among acute care clinical research.

Methods

We performed quantitative and qualitative analysis of docket FDA-1995-S-0036 from its initiation until June 2017 in order to summarize existing practices. We developed a 4-point scoring system to categorize public disclosure and community consultation based on inclusion of key components such as a detailed plan, schedule of events conducted, results, and materials uploaded.

Results

The 177 docket submissions represented 34 trials. Material related to public disclosure accounted for 49% of pages, community consultation 45%, and 6% other. The median Docket Review Content Score for public disclosure was 3 (mean 2.5, range 0 to 4) and 2 (mean 2.1, range 0 to 4) for community consultation materials.

Conclusions

The public information contained in the Docket varies broadly by trial and content. Additionally, as evidenced by the wide range of the Docket Review Content Score, submission guidelines are not followed uniformly. Given the apparent uncertainty about what should be submitted, and the need for best practice recommendations, it is valuable to categorize and summarize existing community consultation and public disclosure content.

Keywords: Exception from Informed Consent (EFIC), Acute Care Research, Public Disclosure, Community Consultation

Introduction

Designing acute care clinical trials can be challenging given the unexpected onset and gravity of the injury or illness being studied. Patients afflicted with traumatic brain injury, shock, and status epilepticus are at high risk for precipitous clinical and mental status deterioration. The combination of a patient’s impaired mental state and a narrow time window to initiate therapy limit the ability to engage these potential participants in a prospective informed consent process. Therefore, such clinical trials often can only be performed under regulations allowing for exception from informed consent for emergency research (21 CFR 50.24).

Implemented in 1996, these regulations impose special requirements on applicable research, such as community consultation and public disclosure. These regulations provide a venue for investigators to communicate with representatives of the study population and act as a potential safeguard for vulnerable populations. The community consultation process provides trial investigators a mechanism to prospectively learn about relevant community values and ascertain concerns about the trial from representatives of the target study population. The public disclosure requirement enhances transparency by ensuring that information related to the study protocol, including benefits and risks, is communicated prior to the start of the trial and that results are disseminated afterwards.

The final regulations and all subsequent guidance documents referring to exception from informed consent for emergency research,1,2 and the 21 Code of Federal Regulations 50.24 require that “information publicly disclosed” be submitted to the FDA Docket-1995-S-0036, which is now available as an internet-based forum that is accessible to the public.3 However, neither the guidance documents nor the regulations language explicates the preferred organization of content for submission to the Docket website. Discrepancies in interpretation of the FDA Docket guidance regarding the specific material submitted and the value of this requirement may be seen as an additional challenge to investigators conducting emergency research. Additionally, there is not an explicit requirement in the guidance about what if any community consultation related information should be submitted, resulting in inconsistencies in posted material.

The FDA Docket represents a potentially valuable source of public information on the development of Federal regulations and other related documents issued by the U.S. government. It remains unclear, however, whether this site provides substantive and useful information related to exception from informed consent trial materials. Given that the content and format of exception from informed consent materials to be submitted has never been specified, we sought to systematically review the current public FDA Docket on community consultation and public disclosure materials for exception from informed consent. It is valuable to examine trends in FDA Docket use in order to understand the application of exception from informed consent regulation. This investigation is a first step toward identifying common practices of public disclosure and community consultation. This categorization can aid in further developing a better understanding of the practices used and their effectiveness, which are necessary goals that have been identified by prior exception from informed consent investigators.4,5 In this study, we aim to characterize the range of materials and practices submitted to the FDA Docket.

Methods

We used a mixed-methods approach to perform a content analysis of FDA-1995-S-0036 accessed on-line at www.regulations.gov/#!docketDetail;D=FDA-1995-S-0036. FDA guidance states, “the sponsor must promptly submit … to Docket Number 95S-0158 … copies of the information that was publicly disclosed prior to initiation of the clinical investigation (e.g., plans for the investigation and its risks and expected benefits).” There is not a requirement for community consultation information to be submitted. According to the FDA guidance (updated April 1, 2016),2 public disclosure is defined as “dissemination of information (i.e., one-way communication) to the community(ies), the public, and researchers about the emergency research.” Community consultation is defined as “providing the opportunity for discussions with, and soliciting opinions from, the community in which the study will take place and the community from which the study subjects will be drawn.” We reviewed all documents uploaded since its inception until June 16th, 2017. There were 177 submissions, which contained 213 PDF files. There were 6,998 pages of materials reviewed and organized by the Investigational New Drug/Investigation Drug Exemption and trial. For each trial, documents were uploaded by investigators, however it was noted that it was uncommon for the included materials to be a labelled or designated as being related to community consultation or public disclosure or something else. Based on the FDA guidance and trial experience of the research team (RS and DH), we separated the number of pages that represented different types of content: community consultation, public disclosure, versus other. Pages of material applicable to both community consultation and public disclosure were split equally between the two content groups and quantified. We categorized the community consultation and public disclosure content by developing a scoring system informed by the FDA guidance to capture the key components (Table 1). For community consultation, we focused on whether the submission included: a detailed plan (i.e., format used), list/schedule of events conducted, results, and material uploaded (survey instrument, survey results, etc.). The public disclosure score was based on the presence of: a detailed plan, list/schedule of events, and materials (website, brochure, etc.) publically disclosed. The maximum possible score was 4 for each content area. Submitted material was also further defined by use of one-way versus two-way communication strategies.

Table 1. Docket Review Content Score.

Scoring informed by FDA guidance related to public disclosure and community consultation.

| Public Disclosure | Community Consultation | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Detailed plan | 1 | Detailed plan | 1 |

| Events listed | 1 | Events listed | 1 |

| Material publically disclosed | 2 | Materials uploaded | 1 |

| Results reported | 1 | ||

| Maximum score | 4 | 4 | |

Results

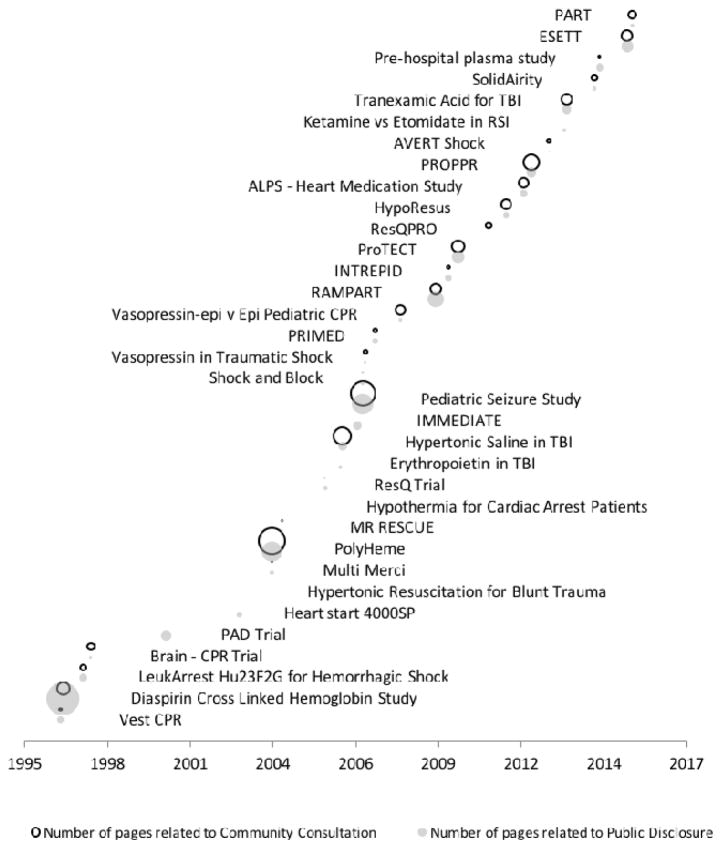

There were 177 submissions to the Docket referring to 34 trials performed under 21 CFR 50.24. Of these trials, 26 were multi-center and 8 were single site trials. The median number of pages per trial was 85 (mean 206, range 2 to 1130). Public disclosure materials constituted 49% of the pages, community consultation 45%, and other documentation related to the trial accounted for the remaining 6%. The median Docket Review Content Score (described in Table 1) for public disclosure was 3 (mean 2.5, range 0 to 4) and 2 (mean 2.1, range 0 to 4) for community consultation materials. The start year and variation in number of pages related to community consultation and public disclosure for each trial are illustrated by the size of the gray or black bubbles in Figure 1. The volume of material per trial decreases over time.

Figure 1. Pages of Public Disclosure and Community Consultation Documentation on Docket.

Thirty-four trials reported in the docket shown by reported start date. Bubble size is proportional to the number of pages submitted that are related directly toward community consultation or public disclosure (as opposed to general trial materials such as Institutional Review Board correspondence or study protocols).

There were a variety of methods used to conduct public disclosure (i.e., format of information delivered). Public disclosure is defined by the FDA as one-way communication with the community, and many trials submitted information consistent with this requirement. As such, information was presented to the public without a concurrent opportunity for the public to respond to that information. There were mass marketing strategies such as marketing through periodicals (newsletters, newspaper articles, press releases, etc.), and other forms of paper marketing (brochures, flyers, posters, bus signs, church bulletins, FAQs sheet, etc.). Some trials used email/web-based resources (online articles, institutional/trial website, social media, etc.). Television and radio modalities were utilized in the form of news stories, public service announcements, press conferences, and closed circuit television. More direct personal communication methods were also used such as letters to physicians/colleagues and mailings to community leaders or leaders of disease-specific organizations. Trials also submitted to the Docket material consistent with community consultation. Events and material where two-way communication was possible were described (i.e. health fairs, and town hall meetings), as well as trial information communicated through professional conferences was submitted. Templates or actual educational materials, notices, advertisements, and other information used for public disclosure were provided for 30 of 34 trials (88%) in the Docket.

The posted public disclosure materials on the Docket reflected three main categories: examples of broad-based materials (i.e., for a general public audience), tailored materials (i.e., for the community with the specific medical condition or medical colleagues delivering care to patients with that medical condition), and metrics of the audience reached. The general public materials posted were in the form of flyers, brochures, TV/radio interview scripts, public service announcements, press releases, posters, website screen shoots, and published articles. Trials also provided estimates of number of people reached, impression (i.e., number of times a website was accessed), community responses, public disclosure participant feedback on activities, and blog/twitter posts. Lastly, there were examples of materials reflecting correspondence sent to a variety of community targets (emergency medical service, community leaders, churches, doctors, colleagues, etc.).

The community consultation process has been conducted using three main modalities: meeting/presentations, survey, or radio. Meetings with community members or leaders were organized as two-way communication, such as town hall discussions, public hearings, health fairs, disease-related support groups, and one-way communication (i.e., presentations slides). Some trials used more professional community consultation forums, such as grand rounds lecture formats. Many trials incorporated surveys that were random-digit dialed, one-on-one, self-administered/mailed, and focus groups. Talk radio was also used to elicit the community opinions and concerns. The community consultation materials posted were similar in character to those used in public disclosure. This included invitation flyers, meeting agenda, Q&A documents/handouts, and presentation slides. The community perspective was elicited using telephone survey, focus groups, and self-administered surveys. Other posted material included the survey templates, telephone scripts, focus group/moderator guides. Trials demonstrated the reach of the community consultation activities by showing lists of attendees/contact lists/sign-in sheets, zip codes of participants, visits to study website, meeting minutes, summaries of feedback, and survey results (individually and in aggregate). Other miscellaneous community consultation postings included participant refusal forms, and Institutional Review Board reports. Other non-community consultation/public disclosure information posted to the Docket included: shipping labels, consent/HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) forms, training manuals, Institutional Review Board correspondence, Investigational New Drug applications, study protocols, publications indirectly related to the trial, responses to deficiencies, Docket cover pages, and blank pages.

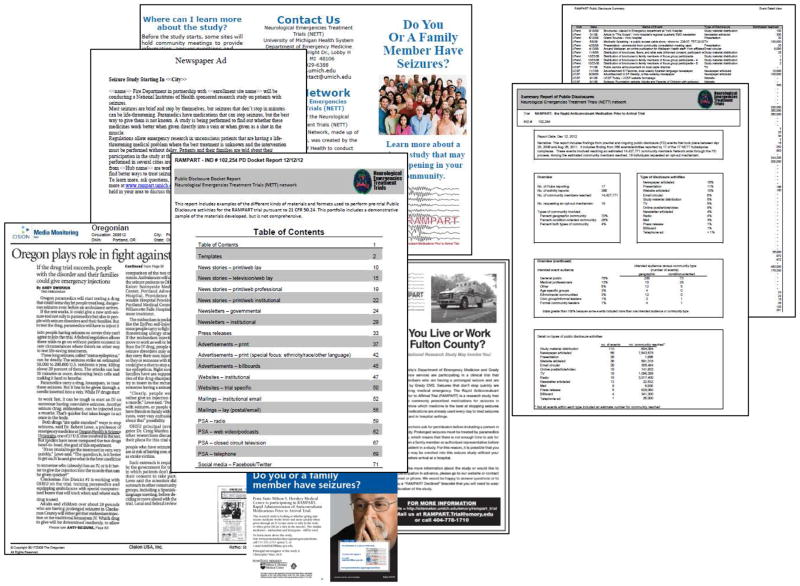

Some multi-center trials provided submissions from each affiliated site, while other trials opted to not submit material from each participating site. The Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials network developed a template for submissions to the Docket for RAMPART (Rapid Anticonvulsant Medication Prior to Arrival Trial) that was also followed for ProTECT III (Progesterone for the Treatment of Traumatic Brain Injury (Experimental Clinical Treatment Trial)), and ESETT (Established Status Epilepticus Treatment Trial). This may represent a potential format to submit data to the Docket (Figure 2) to improve consistency.

Figure 2. Examples of Templates Used for Community Consultation and Public Disclosure.

Examples of Neurological Emergency Treatment Trials Network community consultation and public disclosure materials.

Limitations

The organization and content of the Docket may be influenced by the sponsor or by the Docket management. Therefore, it is difficult to discern the degree to which the variability in the content is shaped by either party. Also, the Institutional Review Board recommendations also influence the content regarding the plans for the community consultation and public disclosure.6,7 Many sponsors appear to have responded to this requirement by posting whatever material was readily available. Posting to the Docket often took place long after completion of the trial, presumably in response to reminders or warnings from the FDA, which may have limited access to source materials that were not otherwise archived. In the absence of: (1) an explicit goal for posting to the Docket, (2) clear guidance on what is required, (3) dissemination of any best practices, and (4) well-defined labels on submitted materials, the content of the Docket does not promote direct comparison across trials. Comparisons and analyses made often required substantial deduction, induction, interpretation and conjecture. The Docket does not capture any information from sponsors that failed to comply with the requirement to post materials. It is unclear how often this happens. There is also no requirement to post community consultation information. Therefore, the summary of community consultations efforts may underestimate the full spectrum of activities performed.

Discussion

Given the absence of a Docket website submissions template for publically disclosed exception from informed consent information and the lack of recent comprehensive analyses of Docket material, we believe it was valuable to categorize and summarize existing community consultation and public disclosure content. Our qualitative evaluation of both community consultation and public disclosure in exception from informed consent trials contained on the FDA Docket revealed a wide range in the Docket Review Content Score, indicating that submission guidelines are not followed consistently from trial to trial. The Docket Review Content Score could help guide Docket submissions in order to provide more consistent reporting across submission content. Our analysis also highlights the wide variety of methods that are being implemented for both public disclosure and community consultation, and is consistent with prior studies that identified variability in community consultation and public disclosure practices as a challenge for exception from informed consent researchers.4,5

Our study also highlights the change in practices over time, which reflects the evolution and development of novel community consultation and public disclosure techniques.8,9 Prior investigators conducted an examination of public disclosure approaches posted on the Docket review up until 1999, and found that among the four trials represented, the predominant disclosure methods were events with minimal engagement or interaction with the target audience. The authors defined these methods as one-way communication and examples included local newspaper advertisements and institutional publications.10 Our summary of publicly disclosed content identified a shift towards two-way communication content, which may represent a departure from the FDA public disclosure guidance. However, this trend may reflect community consultation materials, given that the material submitted to the Docket is not consistently labeled. It is important to note that there is no FDA requirement to publish community consultation materials (other than those involving “information publicly disclosed”), which limits our ability to account for the full spectrum of community consultation practices and determine how these practices have changed over time. This has been a consistent limitation of research describing community consultation activities.5,11 Although limited, our analysis provides a longitudinal catalogue of community consultation approaches and may reflect an increasing focus from trial sponsors to submit it to the Docket.

The public Docket is a potentially rich source of public information about clinical trials conducted under exception from informed consent. However, while the range of materials submitted permits interested parties to view alternative and novel approaches, the lack of any organization for the content of Docket submissions may limit the ability to make substantive comparisons. Our summary of Docket content can inform targeted adaptations to the Docket website in ways to guide investigators submission materials (i.e., providing examples of templates, requiring both community consultation and public disclosure labeling of documents, etc.).

In conclusion, our study provides a comprehensive summary of the common public disclosure and community consultation tools utilized in FDA-regulated acute care clinical trials. Further empiric research (i.e., survey of investigators to quantify common public disclosure or community consultation practices utilized, mixed-methods approaches to better understand the acceptability of strategies from the investigator and participant perspectives, implementation research related to practices utilized, cost, and required effort, etc.) is needed to evaluate these common practices, their effectiveness, and feasibility in order to identify best practices for public reporting of research conducted under exception from informed consent guidelines.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NINDS 5 U01 NS056975 08

References

- 1.Guidance for institutional review boards, clinical investigators, and sponsors. [accessed 21 June 2017];Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research. 2011 https://www.fda.gov/downloads/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM249673.pdf.

- 2. [accessed 21 June 2017];CFR - Code of Federal Regulations Title 21. 2016 1 https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=50.24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [accessed 21 June 2017];Dockets management. 2015 https://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Dockets/default.htm.

- 4.Baren JM, Biros MH. The research on community consultation: an annotated bibliography. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:346–352. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson LD, Quest TE, Birnbaum S. Communicating with communities about emergency research. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:1064–1070. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biros M. Struggling with the rule: the exception from informed consent in resuscitation research. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:344–345. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holsti M, Zemek R, Baren J, et al. Variation of community consultation and public disclosure for a pediatric multi-centered “Exception from Informed Consent” trial. Clin Trials. 2015;12:67–76. doi: 10.1177/1740774514555586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chretien KC. Social media and community engagement in trials using exception from informed consent. Circulation. 2013;128:206–208. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bulger EM, Schmidt TA, Cook AJ, et al. The random dialing survey as a tool for community consultation for research involving the emergency medicine exception from informed consent. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:341–350. 350.e1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugarman J. The role of institutional support in protecting human research subjects. Acad Med. 2000;75:687–692. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah AN, Sugarman J. Protecting research subjects under the waiver of informed consent for emergency research: experiences with efforts to inform the community. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:72–78. doi: 10.1067/mem.2003.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]