Abstract

IgA vasculitis (IgAV) commonly occurs in young children, who present with a tetrad of purpura, abdominal pain, arthralgia and nephritis. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) is a rare complication of IgAV. We herein report an adult case of IgAV with a presentation of DAH and nephritis (pulmonary renal syndrome, PRS), but without other typical manifestations, such as purpura, abdominal pain and arthralgia. A 33-year-old man presented with hemoptysis and a low-grade fever and was diagnosed to have IgAV based on the results of a renal biopsy. Treatment with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis was effective. IgAV should therefore be considered in the differential diagnosis of adult PRS.

Keywords: Henöch-Schonlein purpura, IgA vasculitis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, pulmonary renal syndrome, adult, plasmapheresis

Introduction

IgA vasculitis (IgAV) is a vasculitic disorder which is characterized by the deposition of IgA1-dominant immune complex in small vessels. The formerly-used nomenclature, “Henöch-Schonlein purpura (HSP)”, was replaced by “IgA vasculitis” in the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of vasculitis (1). IgAV usually involves the skin and gastrointestinal tract and frequently results in arthritis, but complications with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) are rare. We herein describe a patient with IgAV who presented with pulmonary renal syndrome (PRS), in which there were clinical manifestations of DAH in the lung and nephritis in the kidneys, but without any typical manifestations of IgAV, such as purpura, abdominal pain, and arthralgia. Based on the diagnosis of PRS, systemic vasculatic disorders such as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) and anti-glomerular basement disease were initially suspected. However, the diagnosis of IgAV was made based on the findings of renal biopsy specimens. Namely, mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with cellular crescents and mesangial IgA deposition were the pathognomonic features of vasculitic disorder in this patient.

Case Report

A 33-year-old man was referred to our hospital because of hemoptysis and a low-grade fever which had lasted for a week. He had no arthralgia, abdominal pain, or skin lesions. He did not have any particular past medical history. He did not take any regular medication. He took loxoprofen sodium hydrate, and expectorant orally after hemoptysis and a low-grade fever occurred. At presentation, the patient's vital status was as follows; height: 165 cm; weight: 90 kg; body mass index (BMI): 33 kg/m2; blood pressure: 179/123 mmHg; body temperature: 37.3°C; heart rate: 104/min; respiratory rate: 16/min; and percutaneous oxygen saturation: 94% with 24% oxygen inhalation via a nasal cannula. Physical examination revealed no skin lesions or abnormal respiratory sounds. Laboratory findings were as follows: total protein: 7.6 g/dL; albumin 3.4 g/dL; alanine aminotransferase: 21 IU/L; aspartate aminotransferase: 23 IU/L; lactate dehydrogenase: 314 IU/L; blood urea nitrogen: 59 mg/dL; creatinine: 7.23 mg/dL; C-reactive protein: 6.36 mg/dL; white blood cell count: 10,200/μL with 80.4% neutrophils and 11.1% lymphocytes; red blood cell count: 3.06×106/μL; hemoglobin 9.2 g/dL; hematocrit: 26.7%; and platelet count: 23.9×104/μL. His serum electrolyte concentration was normal. An arterial blood gas analysis indicated a pH of 7.413, partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood (PaCO2) 36.8 mmHg, partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) 74.4 mmHg, and bicarbonate (HCO3-) 23.1 mmol/L with 24% oxygen inhalation via a nasal cannula.

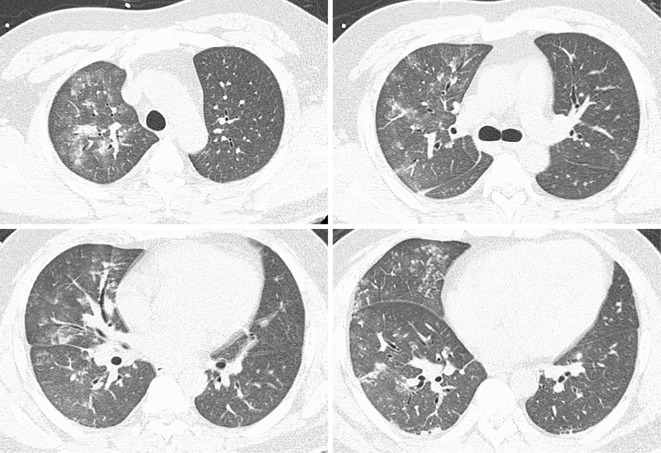

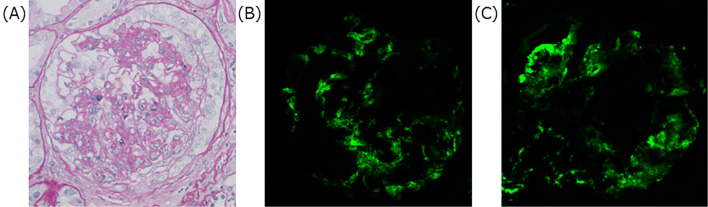

Urinalysis indicated that proteinuria was (2+), microscopic hematuria was (3+) and red blood cells were 10-19/high power field. The red blood cells in the urine were mostly dysmorphic and granular casts were observed. The urine protein to creatinine ratio was 1.24 g/g・Cre. Chest radiography revealed the presence of bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, and a chest CT scan revealed diffuse ground-glass opacity at all levels of the lung fields (Fig. 1). Bronchoscopy was performed and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples indicated an alveolar hemorrhage. Intravenous methylprednisolone (mPSL) of 1 g per a day were administered for three consecutive days along with intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide of 750 mg. Plasmapheresis for three consecutive days was started since we suspected a systemic vasculitic disorder such as AAV and anti-glomerular basement disease. On day two, anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) and ANCA which were examined by immunofluorescence (IF) were reported to be negative. On day five, proteinase-3 ANCA, myeloperoxidase-specific ANCA examined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody were reported to be negative. On day six, a renal biopsy was performed, which demonstrated diffuse mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with cellular crescents in the kidney tissue. An immunofluorescence study demonstrated mesangial deposition of IgA and C3 in the glomerulus (Fig. 2). Electron microscopy showed electron-dense deposits consistent with immune complexes in the mesangial area. We made a diagnosis of IgAV, and oral prednisolone (85 mg/day, 1 mg/kg/day) was administered after intravenous mPSL. This treatment regimen resulted in an improvement of IgAV which was observed on chest radiography. On day seven, his percutaneous oxygen saturation recovered to 94% with no oxygen inhalation therapy. On day 26, a colonoscopy was performed and the tissue of the intestinal wall was shown to be intact by the biopsy specimens, which eliminated the possibility of a gastrointestinal lesion as a complication of IgAV. Considering the severity of IgAV with DAH, additional intravenous cyclophosphamide of 600 mg was administered on day 38 and oral prednisolone was gradually tapered to 55 mg/day before the patient was discharged on day 39.

Figure 1.

Chest CT scan shows diffuse ground-glass opacity at all levels of the lung fields. CT: computed tomography

Figure 2.

Renal biopsy. PAS stain indicates mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with cellular crescents (A). Direct immunofluorescence microscopy shows mesangial IgA (B) and C3 (C) deposition. Original magnification: ×400. PAS: Periodic acid-Schiff

Discussion

According to the findings of this case, we learned two important clinical facts. The first was that IgAV can present PRS in adults without showing other typical manifestations, such as purpura, abdominal pain and arthralgia. Secondly, treatment with combined corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis therapy was effective even though DAH can be a refractory and life-threatening complication.

We consider this case of IgAV to be rare because this patient was an adult who presented initially with PRS, and without any other typical manifestations of IgAV such as purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain. HSP (IgAV) primarily occurs in young children with a peak incidence between 4-7 years (2). Purpura occurs in almost every patient. Arthralgia occurs in approximately two third of cases. Gastrointestinal involvement, including abdominal pain, occurs in approximately two third of cases (3). Previous studies showed that IgAV is generally benign and self-limited in children and more severe in adults (4). Adults had a lower frequency of abdominal pain and fever, and a higher frequency of joint symptoms at disease onset (5). Rajagopala et al. reported the development of DAH in HSP (IgAV) in older children and adult patients. The mean age of onset was 16.5 years (6). Since our case was a 33-year-old man and no skin lesions were observed, IgAV was not initially suspected. From previous reports, a prevalence of 0-5% is suggested for DAH which develops in HSP (IgAV) (7-11). A total of 35 patients with IgAV who presented with DAH showed concurrent purpura at the time of disease onset in previous reports (6). Only one report described HSP (IgAV) complicated with DAH in the absence of purpura, gastrointestinal tract lesions, and arthritis. In that report, however, the patient developed DAH 11 years after the diagnosis of HSP (IgAV), and he exhibited typical purpura at the time of onset of the disease (12). Our case is rare in that he did not exhibit purpura throughout the entire clinical course. IgAV should be considered in the differential diagnosis of PRS in adults even if other typical manifestations of IgAV, such as purpura, arthralgia, and abdominal pain are not observed.

Rajagopala et al. reported 18 cases of HSP (IgAV) with DAH who underwent renal biopsy. Most of these patients showed various degrees of glomerulonephritic change in light microscopy. Furthermore, immunofluorescence was performed in 16 patients, of which 15 demonstrated a deposition of IgA and C3 (6). Glomerulonephritis, which is indistinguishable from IgA nephritis, may occur in IgAV (1). In our patient, the diagnosis of IgAV was made based on findings of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with cellular crescents and mesangial IgA deposition. Another possible examination for the findings of renal biopsy in this case is that IgA nephropathy was superimposed on or overlapping the ANCA-negative AAV. Although ANCA was negative by either indirect IF or the ELISA method, this finding did not rule out the presence of AAV (1). Haas et al. reported 6 cases of ANCA associated crescent glomerulonephritis with mesangial IgA deposits (13).

DAH can be a life-threatening complication of IgAV (HSP) and previous reports have shown a high mortality rate of 27.8% (6). Rajagopala et al. conducted a systematic review and reported that as for the treatment of DAH in HSP (IgAV), combination therapy with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants are reported to be most effective. Among 36 patients of DAH in HSP (IgAV), treatment was as follows: oral steroids alone (11 patients), intravenous mPSL pulse alone (11 patients), combination therapy with corticosteroids and immunosuppressants, such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or cyclosporine A (11 patients), and no treatment (3 patients). The mortality rate was 27.2% for oral steroids, 27.2% for intravenous mPSL pulse alone, 9% for combination therapy, and 100% for no treatment (6). As immunosuppressants added to corticosteroids for the treatment of severe IgAV, cyclophosphamide has been used by analogy with other severe autoimmune diseases (3). However, the addition of cyclophosphamide to corticosteroids for the treatment of severe IgAV still remains controversial. Pillebout et al. compared corticosteroids with or without cyclophosphamide in adults with severe IgAV, in a 12-month, multicenter, prospective, open-label trial, and reported that no difference was found between the two groups (remission rate, renal outcomes, deaths, and adverse events) (14). In this case, considering the high mortality rate of DAH in IgAV, we continued cyclophosphamide along with corticosteroids. Previous studies suggest that patients with either systemic IgAV or renal limited IgA nephropathy have abnormally-glycosylated IgA1 and possibly glycan-specific IgG antibodies that form circulating IgA1-anti-IgA1 immune complexes, which cause inflammation and damage to the organs (15, 16). Hattori et al. reported that plasmapheresis was effective for improving the prognosis of children with rapidly-progressive glomerulonephritis which was caused by HSP (IgAV) (17). Augusto et al. also reported that the combination of plasmapheresis and corticosteroids in adults with severe forms of HSP (IgAV) was associated with a rapid improvement and good-long term outcome (18). The mechanism by which plasmapheresis may improve patients with severe HSP (IgAV) is largely unknown. One possible mechanism is the removal of pathogenic circulating IgA1-containing immune complexes by plasmapheresis (19). Another possible mechanism is the removal of proinflammatory and procoagulatory substances by plasmapheresis. These reports suggest that plasmapheresis is a reasonable adjuvant therapy for treating IgAV patients with DAH. In our experience, the patient was immediately treated with a combination of intravenous mPSL, cyclophosphamide, oral steroids and plasmapheresis, given that we initially suspected a systemic vasculitic disorder. The results of a renal biopsy revealed that IgAV was the cause of PRS and indicated that the continuation of the initial therapy in this patient was reasonable. Since there is not enough data available regarding the optimal treatment for severe IgAV, the diagnosis of IgAV itself did not have great impact on the treatment policy in this case. Further randomized controlled trials regarding the optimal treatment for severe IgAV are thus needed.

In conclusion, our case demonstrated that IgAV can manifest as PRS in adults without showing other typical manifestations, such as purpura, abdominal pain and arthralgia. Treatment with corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and plasmapheresis was effective. We must be aware that IgAV can result in PRS in adults without showing any other typical manifestations. In these cases, a renal biopsy is essential for making an accurate diagnosis of IgAV. Further studies are required to establish the optimal therapeutic strategies for this life-threatening complication of IgAV.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum 65: 1-11, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol 13: 35-40, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audemard-Verger A, Pillebout E, Guillevin L, et al. IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Shönlein purpura) in adults: Diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Autoimmun Rev 14: 579-585, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-Porrúa C, Calviño MC, Llorca J, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children and adults: clinical differences in a defined population. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32: 149-156, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco R, Martínez-Taboada VM, Rodríguez-Valverde V, et al. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adulthood and childhood: two different expressions of the same syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 40: 859-864, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajagopala S, Shobha V, Devaraj U, D'Souza G, Garg I. Pulmonary hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura: case report and systematic review of the English literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 42: 391-340, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in children. Report of 100 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 78: 395-409, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soylemezoglu O, Ozkaya O, Ozen S, et al. Henoch-Schönlein nephritis: a nationwide study. Nephron Clin Pract 112: c199-c204, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cream JJ, Gumpel JM, Peachey RD. Schönlein-Henoch purpura in the adult. A study of 77 adults with anaphylactoid or Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Q J Med 39: 461-484, 1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nadrous HF, Yu AC, Specks U, Ryu JH. Pulmonary involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Mayo Clin Proc 79: 1151-1157, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson JC, Kelly KJ, Pan CG, Wortmann DW. Pulmonary disease with hemorrhage in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Pediatrics 89(6 Pt 2): 1177-1181, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallat BS, Teitel AD. Apurpuric henoch-schönlein vasculitis. J Clin Rheumatol 1: 347-349, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haas M, Jafri J, Bartosh SM, et al. ANCA-associated crescentic glomerulonephritis with mesangial IgA deposits. Am J Kidney Dis 36: 709-718, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillebout E, Alberti C, Guillevin L, et al. Addition of cyclophosphamide to steroids provides no benefit compared with steroids alone in treating adult patients with severe Henoch Schönlein Purpura. Kidney Int 78: 495-502, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1795-1803, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki H, Fan R, Zhang Z, et al. Aberrantly glycosylated IgA1 in IgA nephropathy patients is recognized by IgG antibodies with restricted heterogeneity. J Clin Invest 119: 1668-1677, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hattori M, Ito K, Konomoto T, Kawaguchi H, Yoshioka T, Khono M. Plasmapheresis as the sole therapy for rapidly progressive Henoch-Schönlein purpura nephritis in children. Am J Kidney Dis 33: 427-433, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Augusto JF, Sayegh J, Delapierre L, et al. Addition of plasma exchange to glucocorticosteroids for the treatment of severe Henoch-Schönlein purpura in adults: a case series. Am J Kidney Dis 59: 663-669, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppo R, Basolo B, Roccatello D, et al. Plasma exchange in progressive primary IgA nephropathy. Int J Artif Organs 8 (Suppl 2): 55-58, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]