Abstract

Peripheral itch stimuli are transmitted by sensory neurons to the spinal cord dorsal horn, which then transmits the information to the brain. The molecular and cellular mechanisms within the dorsal horn for itch transmission have only been investigated and identified during the past ten years. This review covers the progress that has been made in identifying the peptide families in sensory neurons and the receptor families in dorsal horn neurons as putative itch transmitters, with a focus on gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP)—GRP receptor signaling. Also discussed are the signaling mechanisms, including opioids, by which various types of itch are transmitted and modulated, as well as the many conflicting results arising from recent studies.

Keywords: Itch, Neuropeptides, Spinal cord, DRG, GPCR signaling

Introduction

Much progress of itch research has mainly been made in peripheral mechanisms, and many important molecular and cellular mediators in both acute and chronic itch conditions have been identified [1] (see other reviews in this issue). In contrast, much less has been elucidated in understanding the mechanisms of itch transmission in the spinal cord. Since the discovery of gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) as an itch-specific neurotransmitter in 2007 [2], further studies have shed light on the spinal mechanisms by which itch is transmitted from the periphery to the brain. Several neuropeptides expressed in the dorsal root ganglia (DRG) have been identified as putative itch transmitters (Fig. 1). In this review, we focus on recent studies of the spinal mechanisms of itch transmission, with a special emphasis on some contradictory studies concerning GRP and GRP receptor (GRP–GRPR) signaling between sensory neurons and the spinal cord. We also highlight what we feel needs to be addressed in the future.

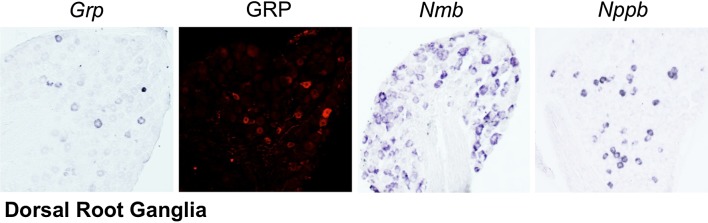

Fig. 1.

Expression of putative itch peptides in dorsal root ganglia. Left, expression of gastrin-releasing peptide (Grp) mRNA by in situ hybridization (ISH). Left center, staining of GRP by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Right center, neuromedin B (Nmb) mRNA expression by ISH. Right, expression of natriuretic peptide B (Nppb) mRNA that encodes brain natriuretic peptide by ISH. Images from the Chen laboratory.

Itch Transmission Through GRP–GRPR Signaling from the DRG to the Spinal Cord

Research on GRP has a long history that can be traced back for almost four decades (for detailed reviews, see [3, 4]). However, only in the past 10 years have researchers been actively exploring how itch information is transmitted from peripheral sensory neurons to the spinal cord. In particular, GRP has been shown to be a key neuropeptide for relaying itch information from DRG neurons to the spinal cord [2]. GRP expression is detectable in a subset of small-to-medium diameter sensory neurons of the DRG as well as in primary afferents of the spinal dorsal horn [2, 5–7]. Expression of its cognate receptor, GRPR, a G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) occurs in superficial lamina neurons of the dorsal horn [2, 8]. One of the first experiments that suggested GRP as an itch neurotransmitter originally came from intrathecal (i.t.) administration of GRP or bombesin, a GRPR ligand first isolated from the fire-bellied toad Bombina bombina, which elicits robust scratching behavior in a dose-dependent manner in rodents [9–11]. However, the physiological significance of these early findings was neglected for decades. In an effort to identify dorsal horn pain-sensing genes, we conducted a genome-wide screen, and found that Grpr showed remarkably restricted expression in laminae I–II of the dorsal horn [2, 12]. Importantly, mice lacking Grpr (Grpr-KO) showed a significant reduction of acute itch behaviors, without changes in pain behaviors [2]. These results provided the first evidence suggesting that GRP–GRPR signaling is specifically required for itch transmission. More strikingly, ablation of GRPR-expressing (GRPR+) neurons using a saporin-toxin conjugated to bombesin, which leads to receptor-mediated internalization of the saporin and subsequent cell death, results in a nearly complete loss of both histaminergic and non-histaminergic itch, whereas pain behavior is not affected [8]. Taken together, these findings suggested that peripheral itch information is transmitted, in part, by GRP release from primary afferents to activate GRPR+ neurons in the dorsal horn. Furthermore, our studies suggested that GRPR+ dorsal horn neurons are dedicated to itch transmission.

Cross-Talk Between GRPR and Other GPCRS

The finding that GRPR is an itch receptor paved the way for a deeper understanding of how a wide spectrum of pruritogens generates itch sensation. For example, opioids are known pruritogens and morphine, commonly used to treat pain in obstetric patients, induces itch [13, 14]. It was thought that opioid-induced itch was due to the inhibition of nociceptive processing. However, it was shown that morphine induces itch via the cross-activation of GRPR by an isoform of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), MOR1D, in mice [15]. MOR1D interacts with GRPR in a heteromeric complex, thereby allowing unidirectional cross-signaling between the two receptors. MOR1, a major MOR isoform for morphine analgesia, is not expressed in GRPR+ neurons. This suggests that spinal morphine administration concurrently activates parallel pathways: MOR1D–GRPR signaling for itch and MOR1 signaling for analgesia. This finding provides further evidence for the concept that itch and pain are relayed by distinct neuronal pathways in the spinal cord. Given the strikingly similar expression of the MOR1D isoform in the superficial laminae of the spinal cord of rats [16], it is very likely that distinct neural mechanisms mediating morphine-induced pruritus and analgesia are conserved across species. However, a recent study has suggested that such a mechanism may not apply to the ascending pathways. Moser and Giesler showed that i.t. morphine administration in rats increases the ongoing activity of itch-responsive trigeminothalamic tract (VTT) neurons, while decreasing the activity of nociceptive VTT neurons [17]. Consistently, no distinct nociceptive- or pruriceptive-specific neurons have been found in spinal or trigeminal projection neurons [18–20]. These findings revive the intriguing possibility that ascending projection neurons may use distinct patterns of activity to relay itch versus pain information, a mechanism that is considered to be outdated.

Recent studies have also revealed that GRPR signaling is subject to descending serotonergic modulation. The 5-HT1A receptor is one of the most abundantly expressed serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) receptors in the spinal cord and has long been implicated in the descending inhibition of inflammatory pain [21, 22]. Mice lacking central 5-HT neurons, as expected, show increased inflammatory pain behavior [23]. Conversely, loss of central 5-HT neurons in mice or loss of 5-HT production in mice lacking tryptophan hydroxylase 2 (Tph2) results in reduced scratching responses to pruritogenic stimuli [24]. Molecular, cellular, biochemical, and biophysical studies suggest that 5-HT facilitates itch transmission in the spinal cord, and 5-HT1A receptors facilitate GRP–GRPR signaling through 5-HT1A–GRPR cross-signaling in heteromeric complexes [24]. Thus, 5-HT1A receptors have opposing actions in modulating itch and pain transmission in the spinal cord. This finding is reminiscent of the MOR1D–GRPR cross-signaling discussed above. Taken together, two common features underlie these findings: (i) Gαi-coupled GPCRs expressed in GRPR+ neurons can cross-activate or -modulate GRPR activity via a process that involves heteromeric interactions, and (ii) Gαi-coupled GPCRs can switch their signaling profiles and activate and/or amplify the non-canonical phospholipase-Cβ/inositol trisphosphate/Ca2+ signaling pathway to relay or facilitate itch transmission (Fig. 2). Thus, GRPR+ neurons may be a unique subset of dorsal horn neurons, which represent a convergence point for the various inputs originating from primary afferents of the DRG and descending fibers from the brain.

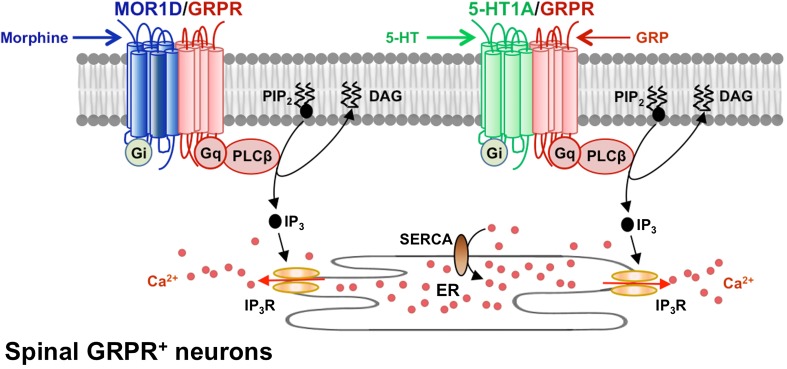

Fig. 2.

Cross-signaling between Gαi-coupled GPCRs and Gαq-coupled GRPR stimulates Ca2+ signaling. Left, upon its activation by morphine, MOR1D cross-activates GRPR, stimulating signal propagation. Right, co-activation of 5-HT1A and GRPR receptors by 5-HT andGRP stimulates PLCβ/Ca2+ signaling and itch propagation. DAG, diacyl glycerol; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; IP3, inositol trisphosphate; IP3R, IP3 receptor; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate; SERCA, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase.

GRP–GRPR signaling is crucial for the development of several types of chronic itch. GRP and GRPR are markedly up-regulated in DRG and the spinal cord of mice with itch associated with dry skin and allergic contact dermatitis [25, 26]. A blockade of GRPR strongly attenuates chronic itch [25, 27, 28]. These findings suggest a therapeutic opportunity for managing chronic itch by targeting GRP–GRPR signaling in the spinal cord. Importantly, increased GRP levels are also found in the serum of patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) [29, 30]. Moreover, transgenic expression of interleukin-22 (IL-22) in the skin resulted in an AD chronic itch model and increased GRP expression in DRG, skin nerve fibers and dermal cells [31]. It is possible that serum GRP may activate GRPR in sensory neurons [32]. These findings strengthen the potential for targeting GRPR not only in the spinal cord but also in the periphery for treating chronic itch. The precise contribution of GRPR in sensory neurons to itch transmission can be further investigated using DRG-specific GRPR-knockout. One caveat is that spinal GRP/GRPR have also been implicated in the reproductive behavior of male rats in autonomic regions of the spinal cord [33]. However, mice lacking GRP/GRPR breed normally [34] (unpublished observations). This indicates that GRP–GRPR signaling is dispensable for normal sexual behaviors in mice. Whether this discrepancy can be attributed to species differences remains to be determined.

One factor contributing to the development of chronic itch is the itch-scratch vicious cycle. It is well known that scratching induces pain to suppress itch [35]. As noted above, scratching-induced pain may induce the release of 5-HT from the brainstem raphe nuclei, which inhibits pain transmission in the dorsal horn via descending inhibitory mechanisms [24]. Because enhanced 5-HT concurrently facilitates GRPR and inhibits nociceptive signaling, increased itch transmission/reduced pain evoke a greater desire to scratch, thereby contributing to the itch-scratch vicious cycle. Therapeutically, it may be possible to target 5-HT1A–GRPR signaling molecules to break the itch-scratch cycle. It is worth noting that 5-HT signaling merely constitutes one of factors that contribute to the itch-scratch cycle, and a detailed discussion of the other factors involved is beyond the scope of this review.

The discovery of GRP as an important itch transmitter and GRPR+ neurons in an itch-specific circuit in the spinal cord raised many more questions concerning itch signal transduction at the local spinal cord level. It remains unclear whether GRPR+ neurons are projection neurons that send itch information directly to the brain or are interneurons that act as a final relay station for itch that forms contacts with local projection neurons. Indirect evidence suggests that GRPR+ neurons do not project to the brain, as their ablation does not significantly affect the expression of neurokinin 1 receptors [8], which are expressed by most projection neurons in the rodent superficial dorsal horn [36]. Subsequent studies in which selected populations of dorsal horn interneurons were ablated using genetic approaches also suggested that GRPR+ neurons are interneurons rather than projection neurons [37, 38]. Future studies using retrograde tracing of spinothalamic or spinoparabrachial tract neurons are needed to test whether GRPR+ neurons of the dorsal horn can be labeled as projection neurons.

Inhibitory Neural Circuits for Itch

An important area awaiting further exploration is the signaling and neural mechanisms underlying itch inhibition in the spinal cord (for a more detailed review on this topic see the Gate control and spinal cord circuit of pain and itch section in this special issue of Neuroscience Bulletin). Recent studies have shown that spinal neurons that transiently express the transcription factor Bhlhb5 (B5), and co-express the endogenous opioid dynorphin during early postnatal development, are important for suppressing itch transmission. Global B5-knockout results in the loss of a subtype of inhibitory interneurons and the development of pathological itch in mice, which is attributed to a loss of dynorphin [39, 40]. However, when dynorphin-expressing (Pdyn +) spinal interneurons are ablated in adult mice using intersectional genetics, it has been shown that Pdyn + neurons are not required for the inhibition of itch, but rather are required for gating mechanical pain [41]. These discrepancies are likely due to a lack of tools to characterize presumptive B5 neurons in adult mice, as B5 neurons have been examined only during an early postnatal stage (P4) due to its transient expression until this stage. The molecular profile of developing B5 neurons may undergo dynamic postnatal changes in the dorsal horn, including neuronal migration and maturation, which do not end until at least 6 weeks of age. Consistent with this, conditional deletion of B5 in mice only results in a partial loss (~49%) of dynorphin expression or Pdyn + neurons in the dorsal horn [41]. It is possible that B5-independent Pdyn + neurons suppress mechanical pain, while Pdyn-negative B5-dependent neurons suppress itch. Because developing B5 neurons are composed of one third excitatory neurons [40], it is also possible that the enhanced itch/pain phenotype of B5-KO mice may be attributed to a loss of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons, resulting in a net effect of central sensitization of itch and pain rather than a loss of inhibition per se. Consistent with studies of the ablation of Pdyn + neurons in the dorsal horn [41], mice lacking dynorphin exhibit acute chloroquine (CQ)-induced itch [39]. These results suggest that early postnatal inhibitory B5 neurons are not identical to Pdyn + neurons in the adult spinal cord and endogenous dynorphin or Pdyn + neurons are not involved in itch inhibition under normal physiological conditions. These observations, however, contrast with the effect of exogenous kappa opioid receptor (KOR) agonists on itch inhibition [42], raising the question of under what conditions endogenous dynorphin may be released to inhibit itch transmission. Given that KOR agonists have been used to treat uremic itch in Japan [42], an in-depth analysis of the mechanism by which activation of the KOR system by exogenous KOR agonists inhibits itch will provide more likely targets to treat itch, circumventing the unwanted adverse side-effects associated with KOR agonists, such as insomnia [43, 44]. Moreover, a recent study using chemogenetic approaches indicated that the selective activation of glycinergic neurons in the dorsal horn is sufficient to inhibit acute itch behaviors [45]. Another population of dorsal horn neurons expressing neuropeptide Y (Npy) mRNA has been identified as a novel inhibitory circuit for mechanical or touch-evoked itch [46]. Selective ablation or silencing of these Npy-expressing neurons results in enhanced mechanical itch behavior, is independent of GRP–GRPR signaling, and does not require GRPR+ neurons, suggesting a pathway within the dorsal horn for mechanical itch that is separate from pruritogen-evoked itch transmission [46]. A key question arising from these studies is whether there exist itch-specific inhibitory circuits that are separable from those involved in the inhibition of pain and other sensory modalities. Research along this line will help elucidate how neural circuits process itch versus pain information in the spinal cord.

The Relation Between GRP and Other Putative Itch Neuropeptides

One important issue is the role of other peptides and receptors in the bombesin family, such as neuromedin B (NMB) and its cognate receptor, NMBR, in itch transmission. NMB is expressed in DRG neurons [47–49] and NMBRs are expressed in superficial dorsal horn neurons, with ~10% overlapping expression with GRPR [48]. Moreover, NMBR+ neurons are excitatory interneurons that form synaptic contacts with spinothalamic and spinoparabrachial tract neurons [48]. Using Nmbr gene-deleted (Nmbr-KO) mice and Nmbr/Grpr double-KO mice, it was found that NMBR and GRPR signaling concomitantly relay histaminergic itch transmission, whereas NMBR is dispensable for acute non-histaminergic itch [48]. It has been suggested that the role of NMB–NMBR in histaminergic itch is masked by cross-signaling between NMB–GRPR, as NMB may act as a functional antagonist for GRPRs [48]. According to the cross-signaling model, a lack of the ligand versus its receptor may give rise to a different cross-talk dynamics in the spinal cord, resulting in a distinct phenotype in mice lacking a single ligand versus its receptor. Another important issue is whether NMBR signaling plays a role in pain or whether there is a compensatory effect between NMBR and GRPR signaling. Although Mishra and Hoon proposed that NMB is important for nociceptive signaling, their conclusion was based on neurogenic inflammatory responses elicited by intraplantar injection of a high dose of NMB as a surrogate for pain [49]. However, exogenous injection of a neuropeptide at a dose likely to be beyond its physiological level may result in a behavioral output that does not reflect its endogenous function. This is particularly true when the nature of behavioral responses induced by exogenous substances is unclear. Intraplantar injection of a chemical irritant is prone to induce neurogenic inflammatory responses which manifest as increased pain hypersensitivity [50, 51]. Thus, it is necessary to distinguish between nociceptive responses induced by exogenous substance/neuropeptides and those evoked in a normal physiological context. Further studies are required to verify whether the induced inflammatory effect is specific to NMBR by the use of NMBR-KO mice. Furthermore, whether NMBR neurons function upstream of GRPR neurons or in parallel awaits further studies. Last, it is still unclear whether NMB and GRP have a redundant function or mediate distinct sets of pruritogenic stimuli. Further phenotypic studies of GRP/NMB and GRPR/NMBR single- and double-knockouts are crucial for improving our understanding of neuropeptide signaling in the coding of itch information in the spinal cord.

Following the findings that peptides and receptors in the bombesin family mediate itch transmission, another family of peptides and receptors was identified as putative itch transmitters. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) has been found to be expressed in a subset of DRG neurons, and one of the receptors in its family, natriuretic peptide receptor A (NPRA), has been detected in the dorsal horn [52]. Deletion of the gene encoding BNP, Nppb, resulted in reductions of both histaminergic and non-histaminergic itch, but acute pain behavior was unaffected for the tests performed [52]. When NPRA+ neurons in the dorsal horn are ablated using BNP-saporin, histamine-induced itch is reduced [52]. It has been suggested that the source of GRP expression is within the dorsal horn, as NPRA+ neurons co-express Grp mRNA. Mishra and Hoon proposed an alternative model that BNP, rather than GRP from DRG neurons activates NPRA/Grp + dorsal horn neurons, which then activate GRPR neurons to transmit itch [52].

The reported findings on BNP–NPRA and GRP–GRPR signaling re-ignited the debate on how the spinal cord mediates itch information from the periphery [26]. One of the main arguments against GRP as an itch transmitter from DRG neurons was that some studies failed to detect Grp mRNA by in situ hybridization (ISH) [47, 52–54], or by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) [55, 56]. However, other studies reported Grp mRNA expression in both uncultured DRG tissues and cultured single DRG neurons using ISH [57], reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with gel electrophoresis [47, 58, 59], or quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) [57], as well as cDNA microarray analysis [60]. To further clarify this issue, a recent study examined Grp expression in a comprehensive manner using ISH, RT-PCR with gel electrophoresis, qPCR, and RNA-seq, and detected Grp mRNA expression with every method used [26]. Compared to other genes expressed in the DRG, Grp is expressed at relatively low levels so some caveats of the methods for detection must be taken into consideration. Despite the low copy-number of Grp in the DRG, Grp mRNA directly prepared from DRGs can easily be amplified by conventional RT-PCR [26]. A lack of Grp-eGFP signal in the DRG of Grp-eGFP transgenic line can be due to the lack of the enhancer element required for site-specific expression in the BAC vectors used to generate DRG-specific expression, which constitutes a major problem with many of the BAC-based transgenic lines. Another key item of data against the linear pathway of BNP–NPRA/GRP–GRPR is that the expression patterns of Grp and Npr1, the gene encoding NPRA, appear to differ in the dorsal horn (Fig. 3). Yet using a Grp-eGFP transgenic line as a surrogate for Grp expression, it was shown that NPRA+ neurons identified by an anti-NPRA antibody completely co-localize with all Grp-eGFP+ neurons in the dorsal horn [52]. This result, which is the pivotal basis of a linear cascade hypothesis, has been challenged for several reasons. First, the specificity of the anti-NPRA antibody used is unclear, in part because the immunohistochemical staining pattern is not consistent with Npr1 expression as detected by ISH [57]. Second, the identical expression patterns of Grp-eGFP and NPRA in the dorsal horn, as presented by Mishra and Hoon, are in conflict with the fact that transgenic eGFP mice rarely recapitulate the endogenous expression of the gene to its full extent. Indeed, it has been reported that only 68% of neurons expressing Grp mRNA are positive for eGFP in the dorsal horn of Grp-eGFP mice, demonstrating the low fidelity of Grp-eGFP mice [53]. Consistently, we also observed poor fidelity of the same Grp-eGFP mouse line, as the expression of Grp-eGFP is much sparser than that of Grp mRNA in the dorsal horn. A third major issue is that the phenotypes were different for mice with ablation of GRPR+ neurons and those with ablation of NPRA+ neurons. Ablation of GRPR+ neurons resulted in an almost complete loss of acute itch behavior for all pruritogens tested, both histaminergic and non-histaminergic, [8] as well as loss of scratching in models of chronic itch [8, 25]. However, only histamine and BNP-induced scratching were presented as being reduced with NPRA+ neuron ablation [52]. If the proposed hypothesis that NPRA+ neurons are the first station in the spinal cord upstream of GRPR+ neurons, then it would be predicted that non-histaminergic acute and chronic itch would be reduced following ablation of NPRA+ neurons.

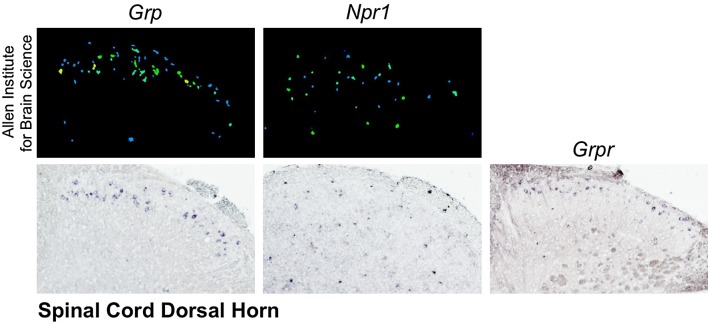

Fig. 3.

Expression of itch peptide and receptor mRNA in spinal dorsal horn. Left, detection of Grp by ISH from (upper panel) Allen Institute for Brain Science [61] and (lower panel) the Chen laboratory. Center, detection of Npr1 by ISH from (upper) Allen Institute for Brain Science and (lower) the Chen laboratory. Right, expression of Grpr by ISH from the Chen laboratory.

If Grp + neurons do not express endogenous GRP or BNP, what is their function in itch and pain? Our unpublished studies indicate that Grp-Cre/eGFP neurons express a mixture of both itch- and pain-sensing genes, including NMBR, GRPR and somatostatin, indicating that they are functionally a heterogenous population in the dorsal horn. Conceivably, an ablation of spinal Grp + neurons could result in a mixture of abnormal itch and pain behaviors. In contrast to many GRPR neurons which express c-Fos after CQ injection [62], a recent study showed that spinal Grp-eGFP neurons minimally express c-Fos or pERK in response to CQ [63]. This finding is consistent with the finding that GRP protein is of primary afferent origin, and not from Grp + neurons in the dorsal horn [25, 26]. One caveat, however, is that it is still possible that the remaining eGFP-negative Grp + neurons in the Grp-eGFP transgenic line may be involved in itch transmission, given that some of them express NMBR or GRPR. Alternatively, Grp-eGFP neurons may have responded to pruritogens but failed to express c-Fos or pERK. To address this issue, one could silence or activate Grp neurons using optogenetic or chemogenetic approaches. This requires the generation of Grp-Cre mice that can fully recapitulate endogenous Grp expression in the spinal cord. Moreover, because Grp mRNA is also abundantly expressed in brain regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex [64], spinal-specific inhibition of Grp + neurons is required to avoid mis-interpretation of the resulting itch/pain phenotype. Nevertheless, as the Grp + neurons are composed of both itch and pain neurons, even the spinal cord-specific ablation or activation is unlikely to be informative.

Interestingly, electrophysiological recordings have shown that dorsal horn neurons exhibit a small overlap between GRP- and BNP-responsive neurons in response to CQ [65]. Since NMBR neurons also respond to GRP due to low-affinity binding [48], some GRPR/NMBR neurons are likely to express natriuretic peptide receptors. Although some histamine-responsive neurons also respond to GRP, none respond to BNP [65], suggesting that BNP cannot activate histamine-responsive GRPR/NMBR neurons. Perhaps most importantly, mice lacking Grp or Grpr show normal i.t. BNP-induced scratching and the specific GRP blocker 77427 fails to attenuate this behavior [57]. These observations again caution against the risk of exclusive dependence on pharmacological approaches to dissect the molecular/neuronal pathways in the spinal cord [48]. Nevertheless, further studies are necessary to determine whether or not NPRA and Grp are co-expressed in the spinal cord and the exact role of BNP–NPRA signaling in itch.

In addition to GRP/NMB/BNP, substance P (SP) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) have also been implicated in spinal itch transmission [66, 67]. However, little is known about how the SP/CGRP signaling pathways relay itch information. It is unlikely that SP-NK1R neurons, as projection neurons, are part of spinal cord circuits that encode itch information. The fact that both SP and CGRP are involved in pain transmission also suggests a lack of specificity for SP and CGRP in sensory modality coding. Little is known about their relation with GRP or NMB; i.e., whether they work synergistically or are required for transmitting particular pruritogenic stimuli. There are more questions than answers concerning the roles of these neuropeptides in itch.

Concluding Remarks

In summary, recent research suggests that GRP/GRPR signaling is important for acute non-histaminergic itch and chronic itch, and spinal cord interneurons encode itch-specific information. GRPR+ neurons may serve as a convergence point that integrates a wide array of pruritogenic information (Fig. 4). On the other hand, many conflicting results exist, some of which can be attributed to the sole dependence on pharmacological approaches or inherent limitations of approaches used. The generation of neuropeptide/receptor-specific cre lines, site-specific deletion, and validation of the drugs used, as well as the application of optogenetics and chemogenetics to itch research should greatly facilitate progress and help to establish a unified framework for incorporating identified signaling components for the transmission of itch information from the periphery to the spinal cord.

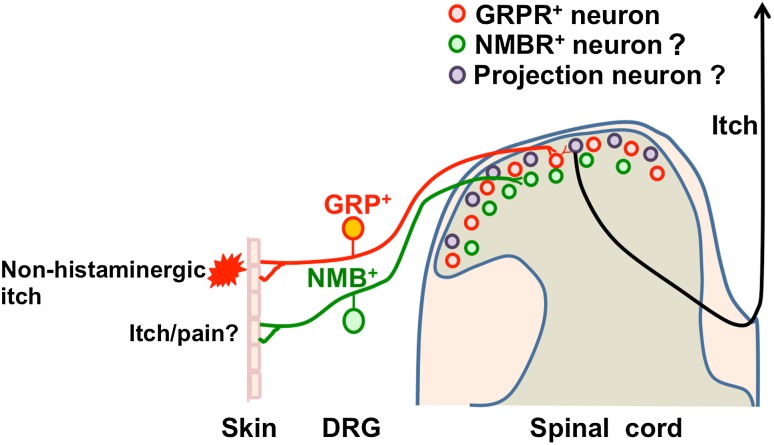

Fig. 4.

Model for itch transmission by GRP-GRPRs and NMB-NMBRs from periphery to spinal dorsal horn. Non-histaminergic itch is transmitted, in part, by GRP from the DRG to GRPR+ neurons in the dorsal horn. The role of NMB/NMBR signaling in the spinal cord and DRG for itch/pain remains unresolved. GRPR+ neurons act as a convergence point for transmitting itch information from the periphery to the brain via spinal projection neurons.

Acknowledgements

D.M.B. was supported by NIH-NIDA T32 Training Grant 5T32DA007261-23 and a W.M. Keck Fellowship. The research work was supported by NIH Grants 1R01AR056318-06, R21 NS088861-01A1, R01NS094344, R01 DA037261-01A1, and R56 AR064294-01A1.

References

- 1.Jeffry J, Kim S, Chen ZF. Itch signaling in the nervous system. Physiology (Bethesda) 2011;26:286–292. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00007.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun YG, Chen ZF. A gastrin-releasing peptide receptor mediates the itch sensation in the spinal cord. Nature. 2007;448:700–703. doi: 10.1038/nature06029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen RT, Battey JF, Spindel ER, Benya RV. International Union of Pharmacology. LXVIII. Mammalian bombesin receptors: nomenclature, distribution, pharmacology, signaling, and functions in normal and disease states. Pharmacol Rev. 2008;60:1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.107.07108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroog GS, Jensen RT, Battey JF. Mammalian bombesin receptors. Med Res Rev. 1995;15:389–417. doi: 10.1002/med.2610150502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Decker MW, Towle AC, Bissette G, Mueller RA, Lauder JM, Nemeroff CB. Bombesin-like immunoreactivity in the central nervous system of capsaicin-treated rats: a radioimmunoassay and immunohistochemical study. Brain Res. 1985;342:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panula P, Hadjiconstantinou M, Yang HY, Costa E. Immunohistochemical localization of bombesin/gastrin-releasing peptide and substance P in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 1983;3:2021–2029. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-10-02021.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moody TW, Thoa NB, O’Donohue TL, Jacobowitz DM. Bombesin-like peptides in rat spinal cord: biochemical characterization, localization and mechanism of release. Life Sci. 1981;29:2273–2279. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90560-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun YG, Zhao ZQ, Meng XL, Yin J, Liu XY, Chen ZF. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science. 2009;325:1531–1534. doi: 10.1126/science.1174868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee H, Naughton NN, Woods JH, Ko MC. Characterization of scratching responses in rats following centrally administered morphine or bombesin. Behav Pharmacol. 2003;14:501–508. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200311000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cowan A, Khunawat P, Zhu XZ, Gmerek DE. Effects of bombesin on behavior. Life Sci. 1985;37:135–145. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90416-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gmerek DE, Cowan A. Bombesin–a central mediator of pruritus? Br J Dermatol. 1983;109:239. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb07091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li MZ, Wang JS, Jiang DJ, Xiang CX, Wang FY, Zhang KH, et al. Molecular mapping of developing dorsal horn-enriched genes by microarray and dorsal/ventral subtractive screening. Dev Biol. 2006;292:555–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bromage PR, Camporesi EM, Durant PA, Nielsen CH. Nonrespiratory side effects of epidural morphine. Anesth Analg. 1982;61:490–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl JB, Jeppesen IS, Jorgensen H, Wetterslev J, Moiniche S. Intraoperative and postoperative analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of intrathecal opioids in patients undergoing cesarean section with spinal anesthesia: a qualitative and quantitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:1919–1927. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199912000-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu XY, Liu ZC, Sun YG, Ross M, Kim S, Tsai FF, et al. Unidirectional cross-activation of GRPR by MOR1D uncouples itch and analgesia induced by opioids. Cell. 2011;147:447–458. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abbadie C, Pan Y, Drake CT, Pasternak GW. Comparative immunohistochemical distributions of carboxy terminus epitopes from the mu-opioid receptor splice variants MOR-1D, MOR-1 and MOR-1C in the mouse and rat CNS. Neuroscience. 2000;100:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser HR, Giesler GJ., Jr Itch and analgesia resulting from intrathecal application of morphine: contrasting effects on different populations of trigeminothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6093–6101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0216-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler GJ., Jr The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10007–10014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2862-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jansen NA, Giesler GJ., Jr Response characteristics of pruriceptive and nociceptive trigeminoparabrachial tract neurons in the rat. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113:58–70. doi: 10.1152/jn.00596.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moser HR, Giesler GJ., Jr Characterization of pruriceptive trigeminothalamic tract neurons in rats. J Neurophysiol. 2014;111:1574–1589. doi: 10.1152/jn.00668.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: brainstem spinal pathways and endorphin circuitry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao ZQ, Chiechio S, Sun YG, Zhang KH, Zhao CS, Scott M, et al. Mice lacking central serotonergic neurons show enhanced inflammatory pain and an impaired analgesic response to antidepressant drugs. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6045–6053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1623-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao ZQ, Liu XY, Jeffry J, Karunarathne WK, Li JL, Munanairi A, et al. Descending control of itch transmission by the serotonergic system via 5-HT1A-facilitated GRP-GRPR signaling. Neuron. 2014;84:821–834. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao ZQ, Huo FQ, Jeffry J, Hampton L, Demehri S, Kim S, et al. Chronic itch development in sensory neurons requires BRAF signaling pathways. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:4769–4780. doi: 10.1172/JCI70528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barry DM, Li H, Liu XY, Shen KF, Liu XT, Wu ZY, et al. Critical evaluation of the expression of gastrin-releasing peptide in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord. Mol Pain 2016, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Lagerstrom MC, Rogoz K, Abrahamsen B, Persson E, Reinius B, Nordenankar K, et al. VGLUT2-dependent sensory neurons in the TRPV1 population regulate pain and itch. Neuron. 2010;68:529–542. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiratori-Hayashi M, Koga K, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Kohro Y, Toyonaga H, Yamaguchi C, et al. STAT3-dependent reactive astrogliosis in the spinal dorsal horn underlies chronic itch. Nat Med. 2015;21:927–931. doi: 10.1038/nm.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tirado-Sanchez A, Bonifaz A, Ponce-Olivera RM. Serum gastrin-releasing peptide levels correlate with disease severity and pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:298–300. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kagami S, Sugaya M, Suga H, Morimura S, Kai H, Ohmatsu H, et al. Serum gastrin-releasing peptide levels correlate with pruritus in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1673–1675. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lou H, Lu J, Choi EB, Oh MH, Jeong M, Barmettler S, et al. Expression of IL-22 in the skin causes Th2-biased immunity, epidermal barrier dysfunction, and pruritus via stimulating epithelial Th2 cytokines and the GRP pathway. J Immunol. 2017;198:2543–2555. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1600126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pereira PJ, Machado GD, Danesi GM, Canevese FF, Reddy VB, Pereira TC, et al. GRPR/PI3Kgamma: partners in central transmission of itch. J Neurosci. 2015;35:16272–16281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2310-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakamoto H, Matsuda K, Zuloaga DG, Hongu H, Wada E, Wada K, et al. Sexually dimorphic gastrin releasing peptide system in the spinal cord controls male reproductive functions. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:634–636. doi: 10.1038/nn.2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hampton LL, Ladenheim EE, Akeson M, Way JM, Weber HC, Sutliff VE, et al. Loss of bombesin-induced feeding suppression in gastrin-releasing peptide receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3188–3192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ikoma A, Steinhoff M, Stander S, Yosipovitch G, Schmelz M. The neurobiology of itch. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:535–547. doi: 10.1038/nrn1950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Todd AJ, McGill MM, Shehab SA. Neurokinin 1 receptor expression by neurons in laminae I, III and IV of the rat spinal dorsal horn that project to the brainstem. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:689–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu Y, Lopes C, Wende H, Guo Z, Cheng L, Birchmeier C, et al. Ontogeny of excitatory spinal neurons processing distinct somatic sensory modalities. J Neurosci. 2013;33:14738–14748. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5512-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X, Zhang J, Eberhart D, Urban R, Meda K, Solorzano C, et al. Excitatory superficial dorsal horn interneurons are functionally heterogeneous and required for the full behavioral expression of pain and itch. Neuron. 2013;78:312–324. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kardon AP, Polgar E, Hachisuka J, Snyder LM, Cameron D, Savage S, et al. Dynorphin acts as a neuromodulator to inhibit itch in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Neuron. 2014;82:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross SE, Mardinly AR, McCord AE, Zurawski J, Cohen S, Jung C, et al. Loss of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord and elevated itch in Bhlhb5 mutant mice. Neuron. 2010;65:886–898. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duan B, Cheng L, Bourane S, Britz O, Padilla C, Garcia-Campmany L, et al. Identification of spinal circuits transmitting and gating mechanical pain. Cell. 2014;159:1417–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Phan NQ, Lotts T, Antal A, Bernhard JD, Stander S. Systemic kappa opioid receptor agonists in the treatment of chronic pruritus: a literature review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:555–560. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kumagai H, Ebata T, Takamori K, Muramatsu T, Nakamoto H, Suzuki H. Effect of a novel kappa-receptor agonist, nalfurafine hydrochloride, on severe itch in 337 haemodialysis patients: a Phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25:1251–1257. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wikstrom B, Gellert R, Ladefoged SD, Danda Y, Akai M, Ide K, et al. Kappa-opioid system in uremic pruritus: multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3742–3747. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005020152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster E, Wildner H, Tudeau L, Haueter S, Ralvenius WT, Jegen M, et al. Targeted ablation, silencing, and activation establish glycinergic dorsal horn neurons as key components of a spinal gate for pain and itch. Neuron. 2015;85:1289–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourane S, Duan B, Koch SC, Dalet A, Britz O, Garcia-Campmany L, et al. Gate control of mechanical itch by a subpopulation of spinal cord interneurons. Science. 2015;350:550–554. doi: 10.1126/science.aac8653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleming MS, Ramos D, Han SB, Zhao J, Son YJ, Luo W. The majority of dorsal spinal cord gastrin releasing peptide is synthesized locally whereas neuromedin B is highly expressed in pain- and itch-sensing somatosensory neurons. Mol Pain. 2012;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhao ZQ, Wan L, Liu XY, Huo FQ, Li H, Barry DM, et al. Cross-inhibition of NMBR and GRPR signaling maintains normal histaminergic itch transmission. J Neurosci. 2014;34:12402–12414. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mishra SK, Holzman S, Hoon MA. A nociceptive signaling role for neuromedin B. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8686–8695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1533-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong Y, Abbott FV. Behavioural effects of intraplantar injection of inflammatory mediators in the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;63:827–836. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.LaMotte RH, Shimada SG, Sikand P. Mouse models of acute, chemical itch and pain in humans. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:778–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mishra SK, Hoon MA. The cells and circuitry for itch responses in mice. Science. 2013;340:968–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1233765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Solorzano C, Villafuerte D, Meda K, Cevikbas F, Braz J, Sharif-Naeini R, et al. Primary afferent and spinal cord expression of gastrin-releasing Peptide: message, protein, and antibody concerns. J Neurosci. 2015;35:648–657. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2955-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wada E, Way J, Lebacq-Verheyden AM, Battey JF. Neuromedin B and gastrin-releasing peptide mRNAs are differentially distributed in the rat nervous system. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2917–2930. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-02917.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Usoskin D, Furlan A, Islam S, Abdo H, Lonnerberg P, Lou D, et al. Unbiased classification of sensory neuron types by large-scale single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:145–153. doi: 10.1038/nn.3881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goswami SC, Thierry-Mieg D, Thierry-Mieg J, Mishra S, Hoon MA, Mannes AJ, et al. Itch-associated peptides: RNA-Seq and bioinformatic analysis of natriuretic precursor peptide B and gastrin releasing peptide in dorsal root and trigeminal ganglia, and the spinal cord. Mol Pain. 2014;10:44. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu XY, Wan L, Huo FQ, Barry DM, Li H, Zhao ZQ, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide is neither itch-specific nor functions upstream of the GRP-GRPR signaling pathway. Mol Pain. 2014;10:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alemi F, Kwon E, Poole DP, Lieu T, Lyo V, Cattaruzza F, et al. The TGR5 receptor mediates bile acid-induced itch and analgesia. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1513–1530. doi: 10.1172/JCI64551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu T, Berta T, Xu ZZ, Park CK, Zhang L, Lu N, et al. TLR3 deficiency impairs spinal cord synaptic transmission, central sensitization, and pruritus in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2195–2207. doi: 10.1172/JCI45414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xiao HS, Huang QH, Zhang FX, Bao L, Lu YJ, Guo C, et al. Identification of gene expression profile of dorsal root ganglion in the rat peripheral axotomy model of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8360–8365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122231899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lein ES, Hawrylycz MJ, Ao N, Ayres M, Bensinger A, Bernard A, et al. Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2007;445:168–176. doi: 10.1038/nature05453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han L, Ma C, Liu Q, Weng HJ, Cui Y, Tang Z, et al. A subpopulation of nociceptors specifically linked to itch. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:174–182. doi: 10.1038/nn.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bell AM, Gutierrez-Mecinas M, Polgar E, Todd AJ. Spinal neurons that contain gastrin-releasing peptide seldom express Fos or phosphorylate extracellular signal-regulated kinases in response to intradermal chloroquine. Mol Pain 2016, 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Cao X, Mercaldo V, Li P, Wu LJ, Zhuo M. Facilitation of the inhibitory transmission by gastrin-releasing peptide in the anterior cingulate cortex. Mol Pain. 2010;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kusube F, Tominaga M, Kawasaki H, Yamakura F, Naito H, Ogawa H, et al. Electrophysiological properties of brain-natriuretic peptide- and gastrin-releasing peptide-responsive dorsal horn neurons in spinal itch transmission. Neurosci Lett. 2016;627:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Akiyama T, Carstens E. Neural processing of itch. Neuroscience. 2013;250:697–714. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rogoz K, Andersen HH, Lagerstrom MC, Kullander K. Multimodal use of calcitonin gene-related Peptide and substance p in itch and acute pain uncovered by the elimination of vesicular glutamate transporter 2 from transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily v member 1 neurons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:14055–14068. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1722-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]