Abstract

Background

The menopausal transition called perimenopause, happens after the reproductive years, and is specified with irregular menstrual cycles, perimenopause symptoms and hormonal changes. Women going through peri menopausal period are vulnerable to bone loss . Osteoporosis is one of the most common debilitating metabolic bone diseases, especially in the women almost around 50 years. This study was intended to evaluate the prevalence of osteopenia/osteoporosis amongst asymptomatic individuals during the menopause transition period.

Methods

A total of 714 asymptomatic peri-menopausal female volunteers were recruited through a billboard invitation for participation in the study. The subjects were selected based on already defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The project, which was conducted between 2010 and 2014 was affiliated to the Educational and Therapeutic Center, Imam Reza Hospital, Mashhad, Iran. Bone Mineral Densitometry (BMD) measured by DEXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) was carried out on two distinct sites, the proximal femur and the lumbar vertebrae from L1 to L4. Pertained data were analyzed.

Results

The mean age of the subjects was 49.7±2.years. The overall prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis in these peri-menopausal individuals were 37.6 % and 10% respectively. Thirty five point two percent of 714 women presented with osteopenia and eight percent of them have osteoporosis in the femoral neck, respectively. Nonetheless, BMD values at the lumbar spine indicated 41.6% and 12% of individual participants being affected by osteopenia and osteoporosis.

Conclusion

In general osteopenia or osteoporosis, occurred in 48% of this study population, implying that special attention is required for the bone health status of Iranian women who undergo menopause.

Level of evidence: II

Keywords: Bone mineral densitometry, Osteopenia, Osteoporosis, Peri-menopause

Introduction

The menopausal transition, perimenopause, starts on average 4 years before the last menstrual period around 42 to 52 years. Its effects on women’s quality of life significantly include a number of physiologic and hormonal changes. The decline of estrogen levels is associated with a variety of devastating problems, majorly bone mass decrease, which causes osteopenia/osteoprois (1-3).

Osteoporosis is one of the most common metabolic bone diseases, with prominent loss of bone mass occurring in more than half of the women around 50 years (4). It is considered as a widely-known health issue across the globe, which is of utmost importance for community with a growing portion of older adults. More to the point, the World Health Organization (WHO) describes it as one of the 4 most chief enemies to human being health, besides cancers, cardiovascular diseases, and strokes. Its annual mortality rate is higher than that of cancers (5). Osteoporosis prevention/treatment is a health necessity in this high-tech sedentary world in which human beings live longer but with limited activity (6). Osteoporosis is associated with declining in bone mass (minerals and matrix). This affects more than half of the women aged 50 or over; put it differently, a virtually large population of 200 million females all over the world. The prevalence of osteoporosis ranges between 4% and 40% based on the reports within distinct regional areas in the world (7). Rapid loss of bone mineral density is on the sharp rise with menopause commencement owing to the loss of ovarian function and a decrease in estrogen production, which, in turn, ends up intensifying activity of osteoclasts in such a way that about 25% to 30% loss in trabecular bones along with 10% to 15% in cortical bones occur throughout the first 5 to 10 years following menopause (8).

The findings of the Iranian nationwide program in osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and treatment have shown osteoporosis and osteopenia in 70% of women and 50% of men above 50 years old (9). At the present time, the osteoporosis myth “once somebody get osteoporosis, no treatment helps” is not heard anymore; but, osteoporosis treatment is still a big dilemma and requires multifaceted approaches including diet and lifestyle changes and a variety of medications that need further investigations (10).

WHO defines osteoporosis as a T-score below -2.5 while osteopenia ranges between -2.5 and -1. A T-score higher than -1 is indicative of normal bone density. Osteoporosis is a heterogeneous disease with unknown etiology. A number of covariates have been reported to influence osteoporosis prevalence, namely smoking, menopause, sedentary lifestyle, aging, calcium and vitamin D deficiency, and respect to medications interfering with vitamin D and calcium absorption like corticosteroid (11).

Materials and Methods

We intended to find out the rate of bone loss in this vulnerable population during the transition period to menaupase and treat this dilemma at a right time. We evaluated BMD in early and also late stage of this climacteric stage of life, as, gradual bone loss during this period is unfortunately still unclear.

Demographics of the patients

This cross sectional study achieved the approval of the ethics committee for medical research affiliated to Mashhad University of Medical Sciences to evaluate BMD on 714 asymptomatic peri-menopause volunteer women who were recruited in hospital through announced billboard advertisement of this project affiliated to the Educational and Therapeutic Center, Imam Reza Hospital, Mashhad, Iran. Informed written consents were obtained from all participants, as well.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

These populations were selected using purposeful sampling method based on inclusion criteria including Iranian nationality living in different regions and provinces; no baseline previous BMD and no specific osteopenia-related treatment; age of menopause between 42 and 52 year (1-3); irregularity or stop of menstrual bleeding for at least 12 months; with intact uterus; and existance of at least one ovary.

The exclusion criteria were an inflammation of connective tissues such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus; chronic inflammatory disease of the lung, liver, and kidney; chronic infectious diseases like osteomyelitis; neoplastic diseases; metabolic bone disease, namely hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, diabetes, and Paget’s disease; bulimia nervosa; anorexia nervosa; a history of pregnancy and lactation within the last year; and use of steroids, anticonvulsants, heparin, thiazides, lithium, tamoxifen, bisphosphonate, and medications affecting vitamin D metabolism and Ca.

Methods of measurement

A questionnaire was initially developed to collect the demographic data including age, age at menarche, age at menopause, gravity, marital status, body weight, BMI, education level, height, and their medications. Out of 1800 peri-menopausal participants in this study, we selected 714 individuals who were at stage of menopausal transitions to perform BMD 7, 12, 13. The test was performed on femur (at four sites including femoral neck, Ward’s triangle, greater trochanter, intertrochanteric line and total hip) and lumbar spine (L1-L4) areas using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA; Osteocore2 Medilink, French). Moreover, T- and Z-score values and fracture risk were determined at the femoral neck and lumbar spine.

Statistics

IBM SPSS v22 was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were applied to report data.

Results

A total of 714 women aged between 42 and 52 years (49.7±2.02) were recruited in the present study. The average weight and length of menopause were reported 69.2±12.51 kg and 154.7±6.07, respectively. Table 1 is showing the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Parameters | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52.9 ± 3.77 |

| Weight(kg) | 70.0 ± 11.55 |

| BMI (kg m-2) | 29.4 ± 4.64 |

| Length(cm) | 154.3 ± 5.61 |

| Menstrual age | 13.3 ± 1.49 |

| Menopause age | 50.0 ± 3.30 |

| Duration of menopause | 2.8 ± 1.5 |

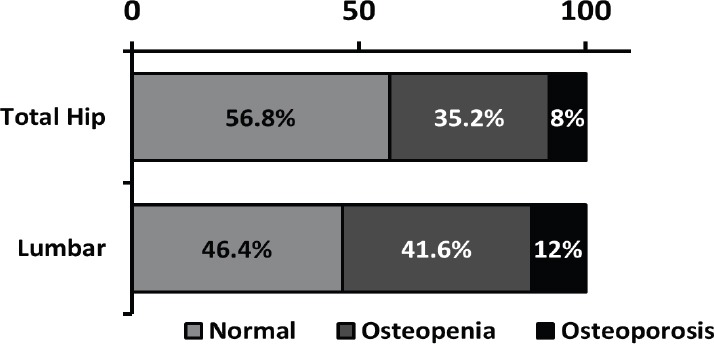

The results of femur BMD indicated that approximately 35% and 8% of the participants had osteopenia and osteoporosis, respectively. The BMD values at lumbar vertebrae (L1 to L4) revealed 42% osteopenia and 12% osteoporosis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Prevalance of Lumbar and Total hip BMD.

We reviewed BMD in two sites; the overall prevalence values for osteopenia and osteoporosis were 37.4% and 10%, respectively. The data on BMD at both femoral and lumbar spine sites were shown in Table 2. Interestingly, the average BMD and T-score were 0.789±0.193 and -0.640±1.099 at the femur; while in lumbar spine these scores reached to 0.926±0.190 and -1.100±1.331 for lumbar spine, respectively.

Table 2.

The results of bone densitometry in femoral neck and lumbar

| Index Variant | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur | BMD | 0.796 | 0.1898 | 0.395 | 1.334 |

| Z-score | -0.34 | 1.119 | -1.60 | 3.50 | |

| T-score | -0.90 | 1.124 | -3.70 | 2.80 | |

| Fracture risk | 2.59 | 2.213 | 0.15 | 12.57 | |

| Lumbar | BMD | 0.902 | 0.1799 | 0.299 | 1.820 |

| Z-score | -0.41 | 1.419 | -1.90 | 4.10 | |

| T-score | -1.20 | 1.363 | -4.50 | 3.60 | |

| Fracture risk | 3.25 | 3.519 | 0.08 | 22.48 | |

Discussion

Osteoporosis is a worldwide metabolic disease which everybody would experience this problem in their life (14, 15).

Decrease of hormone level is the major cause of it. There are a significant researches with respect to post menauposal oeteoporosis but at the present time there is a few investigation in evaluation of bone mass change in peri-menauposal period (16). This study represents starting loss of bone mass before menaupose which is an important issue in preventive medicine in metabolic bone disease.

This study revealed the prevalance of osteopenia in even healthy peri-menauposal women is not uncommon and the loss of bone mass may start earlier than the age of menaupose . The limitation of our study is the factor of regional focus and number of population- specific in Mashad City.

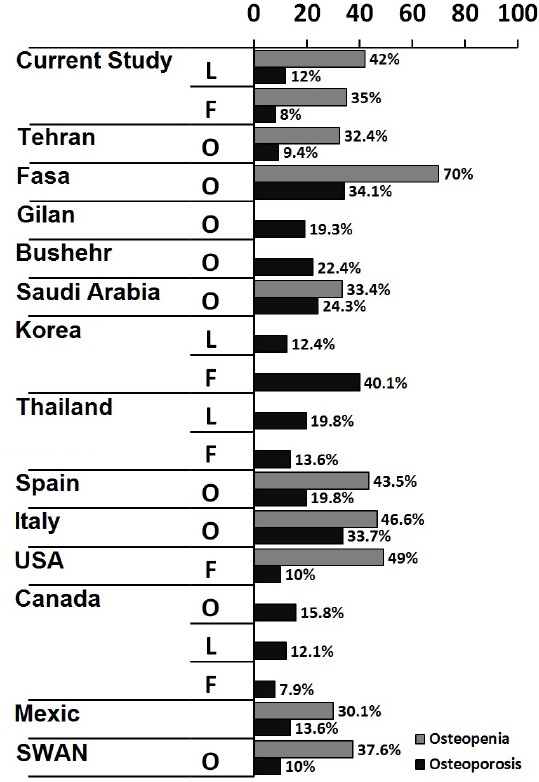

Majority of the available information about the endocrine and clinical manifestations of the menopausal transition comes from a number of longitudinal cohort studies on midlife women (3), the largest of which, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN), has followed a multiethnic, community-based cohort of over 3000 women aged 42 to 52 years for 15 years (1-3). The prevalences of osteopenia and osteoporosis among women from varios geographical areas are summarized in Figure 2 (16-18).

Figure 2.

The prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis based on Overal (O), Lumbar (L), and Femural (F) BMD in various geographical regions (Current study in Mashhad, Iran (our study); Tehran, Iran (11,15); Fasa, Iran (19); Gilan, Iran (19); Bushehr, Iran (19); Saudi Arabia (20,17); Korea (21); Thailand (18); Spain (22); Italy (23); USA (24); Canada (25); Mexic (4); and the SWAN study (1);).

The discrepancy among the previous studies and our findings can be attributed to the following reasons: Firstly, previous studies have evaluated different and elder populations (post menopause). Secondly, previous studies have performed in different geographical regions with different genetic backgrounds, ethnic groups, lifestyles, diets, and habits 17, 18, 20. Lastly, we would like to emphasize that the strength point of our study, is adopting a broad spectrum of exclusion criteria which pinpointed asymptomatic peri-menopausal women.

Likewise, the findings of our investigation descriptive and analytic investigation were in broad agreement with the reports from Europe (Spain and Italy) (21, 22).

When it comes to North America, there has been disparity and consistency among different studies in this issue. One of the most significant factors responsible for increased prevalence of osteoporosis in developed countries is most probably because of the aged baby-booming generation.

It seems that discrepancies between our study and other studies around the globe, focusing on prevalence of the osteopenia/osteoporosis, arise from the ethnic features, geographical factors, lifestyles, physical activity and different diet (14, 15, 17, 20). Additionally, the maximum peak bone mass is noticable in determining the prevalence of osteopenia/osteoporosis, in which, genetics, gender, race, nutrition, life style, medicines, habits, attitude and altitude statues play pivotal roles (16, 18). It was reported that the peak bone mass in Iranian women was lower than their peers in other countries across all age groups (7).

The limitation of our study was the number of normal population of perimenauposal women who

Osteopenia/osteoporosis (Low bone mass) are hidden, major health concerns for our society because of their quiescence nature of the bone loss process with no sign and symptoms until a fracture happens. The significant message in this study is to address the prevalence of early onset of osteopenia/osteoporosis in peri-menopausal women in our society.

Forty eight percent of our participants had osteopenia or osteoporosis during their first five years following menopause. The rest of individuals (52%) revealed normal BMD. Therefore, it could be concluded that the bone health status of peri-menopausal women in Iran is warning big issue which requires much more attention of authorities like government and health policy makers to adopt preventive programs for screening bone health statues in susceptible women around the time of menopause. Rising awareness and educating the community regarding bone health acquirement preserving through achieving peak bone mass from birth even intrauterine-growth to adulthood, having healthy and fully active lifestyle is a necessity. Therefore, we may be able to reduce the pace of bone loss in half or more of our vulnerable population at risk.

Authors declare no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

Aknoledgement

We would like to show our gratitude to Mrs F.Iravani for her cooperation in our research follow up cases.

References

- 1.Bromberger JT, Schott LL, Kravitz HM, Sowers M, Avis NE, Gold EB, et al. Longitudinal change in reproductive hormones and depressive symptoms across the menopausal transition: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(6):598–607. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janiszewska M, Firlej E, Dziedzic M, Zolnierczuk-Kieliszek D. Health beliefs and sense of one's own efficacy and prophylaxis of osteoporosis in peri- and post-menopausal women. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2016;23(1):167–73. doi: 10.5604/12321966.1196875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Voorhis BJ, Santoro N, Harlow S, Crawford SLR, andolph J. The relationship of bleeding patterns to daily reproductive hormones in women approaching menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):101–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31817d452b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castro JP, Joseph LA, Shin JJ, Arora SK, Nicasio J, Shatzkes J, et al. Differential effect of obesity on bone mineral density in White, Hispanic and African American women: a cross sectional study. Nutr Metab. 2005;2(1):e9. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoury MJ. Genetic and epidemiologic approaches to the search for gene-environment interaction: the case of osteoporosis. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castrogiovanni P, Trovato FM, Szychlinska MA, Nsir H, Imbesi R, Musumeci G. The importance of physical activity in osteoporosis From the molecular pathways to the clinical evidence. Histol Histopathol. 2016;31(11):1183–94. doi: 10.14670/HH-11-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larijani B, Tehrani MR, Hamidi Z, Soltani A, Pajouhi M. Osteoporosis, prevention, diagnosis and treatment. J Reprod Infertil. 2005;6(1):5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsao LI. Relieving discomforts: the help-seeking experiences of Chinese perimenopausal women in Taiwan. J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(6):580–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smeets-Goevaers CG, Lesusink GL, Papapoulos SE, Maartens LW, Keyzer JJ, Weerdenburg JP, et al. The prevalence of low bone mineral density in Dutch perimenopausal women: the Eindhoven perimenopausal osteoporosis study. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(5):404–9. doi: 10.1007/s001980050083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shariat-Sarabi Z. Understanding osteoporosis aims to boost our bone health. J Case Reports Pract. 2016;4(3):19–21. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akbarian M. Epidemiology and the importance of osteoporosis Rheumatology Research Center. Tehran: Andishmand, Tehran University of Medical Sciences; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirazi KK, Wallace LM, Niknami S, Hidarnia A, Torkaman G, Gilchrist M, et al. A home-based, transtheoretical change model designed strength training intervention to increase exercise to prevent osteoporosis in Iranian women aged 40-65 years: a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(3):305–17. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soltani A, Sedaghat M, Adibi H, Hamidi Z, Shenazandi H, Khalilifar A, et al. Risk factor analysis of osteoporosis in women referred to bone densitometry unit of Endocrinology and Metabolism Research Center of Tehran University of Medical Sciences. Iran South Med J. 2002;5(1):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharami SH, Milani F, Alizadeh A, Ranjbar ZA, Shakiba M, Mohammadi A. Risk factors of osteoporosis in women over 50 years of age: a population based study in the north of Iran. J Turkish German Gynecol Assoc. 2008;9(11):38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amiri M, Nabipour I, Larijani B, Beigi S, Assadi M, Amiri Z, et al. The relationship of absolute poverty and bone mineral density in postmenopausal Iranian women. Int J Public Health. 2008;53(6):290–6. doi: 10.1007/s00038-008-8033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rowe SM, Jung ST, Lee JY. Epidemiology of osteoporosis in Korea. Osteoporos Int. 1997;7(Suppl 3):S88–90. doi: 10.1007/BF03194350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadat-Ali M, Al-Habdan IM, Al-Mulhim FA, El-Hassan AY. Bone mineral density among postmenopausal Saudi women. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(11):1623–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Limpaphayom KK, Taechakraichana N, Jaisamrarn U, Bunyavejchevin S, Chaikittisilpa S, Poshyachinda M, et al. Prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis in Thai women. Menopause. 2001;8(1):65–9. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200101000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larijani B, Hossein-Nezhad A, Mojtahedi A, Pajouhi M, Bastanhagh MH, Soltani A, et al. Normative data of bone Mineral Density in healthy population of Tehran, Iran: a cross sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2005;6(1):e38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-6-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Desouki MI. Osteoporosis in postmenopausal Saudi women using dual x-ray bone densitometry. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(9):953–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cui LH, Choi JS, Shin MH, Kweon SS, Park KS, Lee YH, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis and reference data for lumbar spine and hip bone mineral density in a Korean population. J Bone Miner Metab. 2008;26(6):609–17. doi: 10.1007/s00774-007-0847-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guzman Ibarra M, Ablanedo Aguirre J, Armijo Delgadillo R, Garcia Ruiz Esparza M. Prevalence of osteopenia and osteoporosis assessed by densitometry in postmenopausal women. Ginecol Obstet Mex. 2003;71(1):225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.D'Amelio P, Spertino E, Martino F, Isaia GC. Prevalence of postmenopausal osteoporosis in Italy and validation of decision rules for referring women for bone densitometry. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92(5):437–43. doi: 10.1007/s00223-013-9699-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Looker AC, Melton LJ, 3rd, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA. Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005-2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(1):64–71. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown JP, Fortier M, Frame H, Lalonde A, Papaioannou A, Senikas V, et al. Canadian consensus conference on osteoporosis, 2006 update. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(2 Suppl 1):S95–112. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)32087-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]