Abstract

Chinese Medicine (CM) suggests that the root of all disease lies in separation from the Tao, which occurs when Yin and Yang differentiate. Chong Mai–focused acupuncture can theoretically address this level, but an adjusted therapeutic approach could be necessary to produce the best results. In this article, the author explores some context and needling strategies used to work effectively with the Chong Mai in a unique way.

Keywords: : Jing, Chong Qi, Yuan Qi, Source Qi, Original Energy, Yin, Yang

Introduction

Acupuncture is an effective tool for addressing musculoskeletal issues (Wei level) and various system disturbances (Ying level). Indeed, it is probably most frequently used at these levels. However, experience often teaches that, while superficial conditions come and go like waves on the surface of the ocean, these conditions are often fueled by deeper (Yuan level) currents in the ocean.

Here, the philosophy of Chinese Medicine (CM) can prove particularly pertinent because it returns us to the beginning. Yin and Yang separation occurs with the dawning of personal awareness. At the moment when we realize we exist, we also sense we are separate from other things. This primal differentiation is the source of all subsequent suffering, because without self-awareness, the very concept of illness could not exist. In CM, the relationship between Yin and Yang is known as the Chong Qi. This Qi is experienced as pleasant when allowed to flow freely. But many people find it unpleasant, especially those who have had difficult or traumatic childhoods. Perhaps their Chong Qi is not flowing as freely as it might.

Regardless of upbringing, many people tend to spend a lot of time worrying about relatively minor symptoms, only to become calm and philosophical when diagnosed with a serious or terminal disease. CM refers to this phenomenon as latency. For example, it is not uncommon to observe that patients with a condition such as rheumatoid arthritis often seem gentle and accepting of their circumstances. It is as if all these patients' anger, grief, and sadness has been put into storage. Although it is perhaps impolitic to suggest that the illnesses might be a metaphorical expression of the Jungian shadow, CM's notion of latency suggests that such a statement may be close to the mark.

For some people, perhaps a more creative way of dealing with existential anxiety would be to let it flow more freely. That way, the inherent joyfulness of the Chong Qi might infuse itself into daily experience. In this article, I explore the notion of going directly to this primal Qi through a somewhat innovative use of the Chong Mai.

Transformation: The Golden Gate

Existential angst seems to be fundamental to Western consciousness. In Christian mythology, human beings were thrown out of the primeval state (Eden), each in order to build a separate self. In the process, people become alienated from their original wholeness. In contrast, in the Taoist view, no-one is thrown out of anything. Instead, the human being takes the place of the Chong Qi, in charge of the relationship between Yang and Yin.1 This puts the human at the very center of things, totally connected and relevant. When people experience this connection, existential anxiety is often transcended and many troublesome symptoms seem to be less problematic.

However, shifting one's perspective from alienation to connection is not necessarily easy. One CM image that refers to the transition is that of the Golden Gate. The Gate is an imaginary pass through which the ego must travel to transcend itself and forge a more-integrated identity.2 The passage lies between the Metal and Water phases; and it is here that the ego dissolves back into the formlessness of the Tao. Gate transition drops the traveler, at least temporarily, out of the 5-phases into the primordial Yin/Yang relationship. Seeing this shift occur during an acupuncture session can be inspiring. The challenge then becomes how to go forward and maintain it.

Establishing a Non-Dual Acupuncture Context

Modern science and conventional allopathic medicine are both philosophically rooted in duality. The divisions of observer and observed, practitioner and patient, diagnosis and treatment, health and illness, all seem self-evident and sensible. However, in this model, treatment tends toward acting against, with medications such as antibiotics, anti-inflammatories, antidepressants, and the like. Although the limitations of allopathy are becoming increasingly apparent, alternatives, such as dietary and lifestyle modifications, are rarely paid much more than lip service.

In contrast, CM symptoms are generally categorized as a pattern of Disharmony, or ascribed to a 5-Phase Constitutional imbalance. Treatment strategies are then designed to balance the Disharmony. While the approach is theoretically rooted in non-dualism, in practice, dualistic assumptions remain, albeit in more-subtle form. Practitioner and patient remain separate; symptoms are still viewed with suspicion; and treatment for many conditions, such as pain, for example, may still veer toward the notion of acting against.

Because of such collective conditioning, the allopathic perspective often permeates the acupuncture therapeutic relationship, even though it does not really belong there. The bias assumes, a priori, that something is wrong, which is precisely the same assumption that defines the ego's alienation in the first place. Consequently, the familiar therapeutic milieu might, itself, be a constraint to the free flow of Chong Qi.

When patients traverse the Gate, they may find themselves in an unusual state where everything seems to be right. This reversal signals a fundamental perspective shift toward non-duality. If the therapeutic relationship does not shift simultaneously, it may risk inadvertently retarding future progress by maintaining the artificial duality.

Transforming the therapeutic relationship involves a shift toward a dyad of equal partners, rooted in the not-knowing of the Tao.3 In this dyad there is no patient, no practitioner, no separation, no illness, and therefore paradoxically, nothing to treat. That is not to say there are no symptoms. They remain, of course, but are not necessarily understood as pathologic. Rather, they become more like informational signals, used to guide point location from a more experiential perspective.

In the non-dual context, root assumption shifts from something is wrong to something is right; intention shifts from moving away to moving toward. Traditional roles are reversed: the patient (formerly inactive or Yin) becomes more active (Yang), an explorer who expresses symptom curiosity. Meantime the practitioner (formerly active or Yang) becomes less active (Yin), a witness to the exploration. Theory drops to second place. What previously was two, becomes one. Readers should note that the non-dual therapeutic relationship does not preclude hierarchy, but recognizes an equivalent reverse hierarchy within the dyad (i.e., the practitioner has more knowledge of acupuncture, while patients have more knowledge of themselves).

The transformed milieu gives rise to a different kind of acupuncture, not grounded in the usual diagnosis and point prescription approach. With no 5-Elements tints and no TCM patterns to worry about, the Chong Mai and other Extraordinary Meridians (EMs) form a good framework for needling options. The process is less about reinventing the EM trajectories (which have been well-described elsewhere),4,5* but rather about reframing the use of the Chong Mai in the context of non-duality and returning to the Tao.

Historical Overview

Extraordinary Channel treatments were not common before the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 ad).* Prior to this, it was considered improper to work on the Constitutional level. The restriction began to loosen during the Song Dynasty (960–1279 ad) through the philosophical input of Zhu Xi (1130–1200 ad), a Confucian scholar who came up with the notion that human beings were not necessarily victims of Divine will. On the contrary, personal will (Zhi) puts a person, at least to some degree, in charge of his or her own destiny. With that premise, the notion of accessing and influencing the Source and Jing through the Chong Mai became more acceptable.

Accessing the Yuan Qi (Original Energy)

In traditional CM theory, Jing, or Yuan (Source, or Chong) Qi, enters the body through the Chong Mai and is distributed via the Triple Heater and Du Mai to the Bladder Shu points and then to the primary meridian Source points. Given that the primary channel system represents the necessities of survival and social conditioning (postnatal Qi), there are always layers of unrealized potential (Jing) left behind at the Source.

Some of this original energy may lie latent in the CM organs (as a disease), and so could theoretically be accessed through the Distinct channels.5 Some is also resident in channel Source points. Bladder Shu and Front Mu points are good reservoirs as well. At the end of the day, all points holding Stagnant energy are little minireservoirs of Yuan Qi. However, truly, the ultimate reservoir is going to be the Chong Mai itself.

The Chong Channel

The Chong Mai is generally regarded as an architectural blueprint, containing prenatal, genetic, and ancestral influences. Not limited to any specific primary channels, it has been said to go everywhere and do everything.5 It is most active in utero, but continues activity until a person is 6 or 8 years of age. The Chong Mai connects to all the other EMs, and all the primary channels. Given that it is so all-encompassing, it is hard to imagine how the Chong Mai could have linear features and specific points. Perhaps it really does not. Perhaps when working with the Chong Mai, any point will do provided the choice arises out of the non-dual relationship in a spontaneous way. That has certainly been my experience.

Nevertheless, the Chong Mai has been described as having a trajectory and points, perhaps because, without some kind of structure, it would be difficult to conceptualize. In The Eight Extraordinary Channels, Qi Jing Ba Mai: A Handbook for Clinical Practice and Nei Dan Meditation 4 David Twicken, DOM, LAc, describes 5 branches (Figs. 1 and 2):

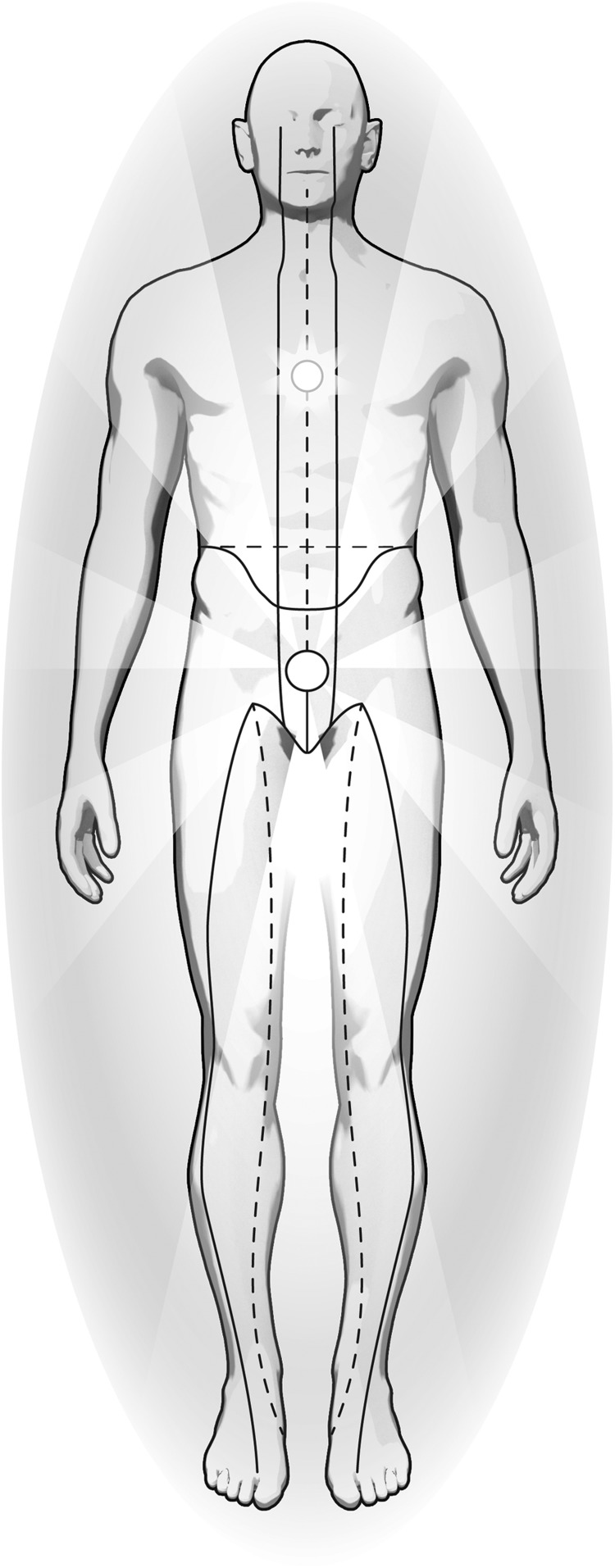

FIG. 1.

The Chong Mai and Dai Mai. Forward view with dotted lines indicating posterior trajectories. Graphic by Richard Greenwood, BFA, MA, and used with permission.

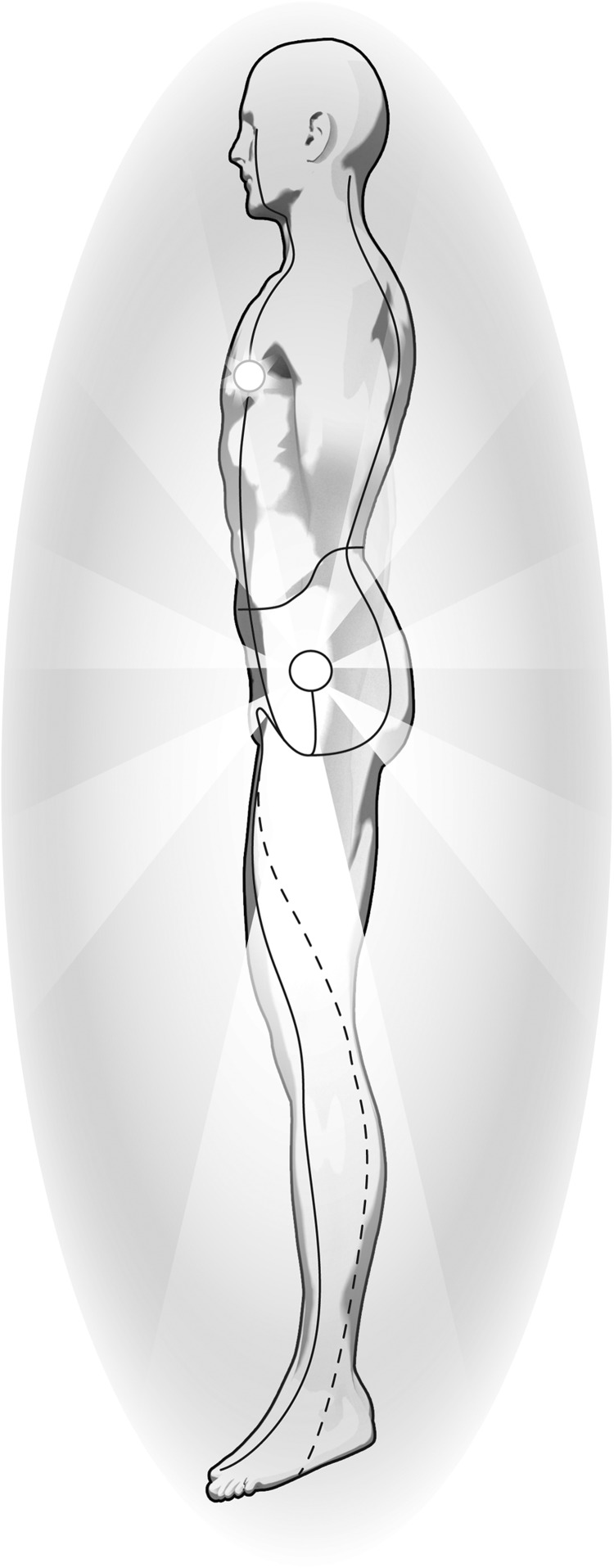

FIG. 2.

The Chong Mai and Dai Mai. Side view with dotted lines indicating posterior trajectories. Graphic by Richard Greenwood, BFA, MA, and used with permission.

(1) The first branch begins in the lower abdomen (Ming Men) and emerges at the perineum at CV 1 (Huiyin). From there, the branch travels up the spine to GV 16 (Fengfu), giving rise to the Du Mai, which proceeds on to the crown. The branch's path, along with the Du Mai, has been equated with the Sushumna of Ayurvedic Medicine (the pathway of Kundalini, which runs from the base of the spine to the crown.6

(2) The second branch flows from Huiyin to ST 30 (Qichong) and KI 11 (Hengu). From there, the branch ascends the front of the body along the Kidney channel to KI 21 (Youmen), giving rise to the Ren Mai, and connecting the Kidneys to the Heart. The branch then passes through the chest Kidney Shu points (KI 22 to KI 27) and disperses into the chest.

(3) The third branch ascends along the throat, curves around the lips, and terminates below the eyes.

(4) The fourth branch emerges at ST 30, and descends the medial legs to the popliteal fossa, and down behind the medial malleolus to the sole of the foot, giving rise to the Yin Wei and Yin Qiao vessels. The branch passes through SP 10 (Xuehai), KI 10 (Yingu), and BL 40 (Weizhong).

(5) The fifth branch emerges at ST 30 and flows down to ST 42 (Chongyang), LR 3 (Taichong), LR 1 (Dadun), and SP 1 (Yinbai). See Figure 1.

Overall, that is a fair assortment of the branches, and an awful lot of potential points for one Meridian. Furthermore, if the other EMs are added to the matrix, all of which arise from the Chong Mai, the result is a panoply of points located pretty much anywhere and everywhere.

The Ancestries

The Chong Mai gives rise to the Ren, Du, and Dai Mai, a group known as the First Ancestry (Table 1). The Du and Ren arise from the Chong Mai and complete a circuit from the pelvic floor (CV 1) to the crown (GV 20 (Baihui) and return. The Dai Mai encircles the waist, giving rise to various degrees of separation between the pelvic energies and the Heart Shen. I have discussed this concept elsewhere.6 Given that all 3 channels arise from the Chong Mai, in my opinion, they can all be regarded as extensions of the original Chong.

Table 1.

Chong Mai & Other Extraordinary Meridians (EMs)

| Ancestry | EM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| First | Chong Mai | The Mother; primordial, connects the prenatal to postnatal |

| Ren Mai | Bonding, structure, Yin or “nutrition, connection, & containment” | |

| Du Mai | Individuation, activity, Yang | |

| Dai Mai | Everything we have stuffed away | |

| Second | Yin Wei Mai | How we look during the cycles of 7 & 8 |

| Yang Wei Mai | How we behaved during the cycles of 7 & 8; with capacity & resources | |

| Yin Qiao Mai | How we feel about ourselves right now, today, comfortable or uncomfortable | |

| Yang Qiao Mai | How we view the world, right now today—activist or pacifist |

As for the Second Ancestry channels, the same argument applies, with the additional observation that the Opening and Coupled points are all the same as those of the First Ancestry. Taken as a whole then, the other 7 EMs might simply add a large range of usable points within the context of the Chong Mai umbrella.

No doubt the more a practitioner knows about the whole family of EMs, the better. Yet, there is a lot to know in CM, and complexity can inadvertently maintain the subtle dualism one is trying to transcend, especially if the practitioner gets lost in mental gymnastics. To avoid this difficulty, and to give the less-experienced physician a way to begin, perhaps acupuncture theory could be kept as simple as possible, and point choices could be a mutual affair. Here the Chong Mai/EM system excels. So, for practitioners who are eager to try things out, it is worth reiterating that the entire set of EMs can be reduced to a remarkable simplicity: a small variety of starting gambits based on 4 pairs of Opening/Coupled points, followed by intuitive point choices arising out of a non-dual therapeutic dyad (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Opening & Coupled Points of the Extraordinary Meridians

| Ancestry | Channel | Opening points | Coupled points | Other key points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Chong Mai | SP 4 | PC 6 | KI 11→KI 27 & ST 30 |

| Ren Mai | LU 7 | KI 6 | CV 15 | |

| Du Mai | SI 3 | BL 62 | GV 1, GV 12 & GV20 | |

| Dai Mai | GB 41 | TH 5 | GB 26→GB 28 & LV 13 | |

| Second | Yin Wei Mai | PC 6 | SP 4 | KI 9 |

| Yang Wei Mai | TH 5 | GB 41 | GB 35 | |

| Yin Qiao Mai | KI 6 | LU 7 | KI 8 & BL 1 | |

| Yang Qiao Mai | BL 62 | SI 3 | BL 59, BL 1 |

The Chong Mai in Practice

Why then, isn't the Chong Mai used more often? The answer perhaps is because it is usually used as if it were a primary channel, although it is not a primary channel.

To put this another way, it is not good to just use the Opening and Coupled points in a conventional context because this will only activate the Primary Meridians.

The challenge of using the Chong Mai effectively lies in moving beyond formulas and seeing the symptoms as part of the wholeness of the therapeutic dyad, wherein the symptoms themselves choose the points. This difference is not just semantic, but has to do with states of consciousness. Given that the Chong Mai is a blueprint that exists prior to the emergence of ego, to engage the Chong Mai, both practitioner and patient need be in a transpersonal state of consciousness. Furthermore, when original energy surfaces, the ego needs to stay back, observe, and resist the temptation to intervene. Primal energies can be powerful and sometimes scary. As Andrew Nugent-Head once put it, “Qi is not some wimpy thing.”7

Dynamism

One approach that facilitates the flow of Yuan Qi is to make the acupuncture process more interactive, using a technique termed Dynamic Interactive Acupuncture (DIA). This is performed by changing a few parameters at the outset of a session.

First, the explorer breathes in with needle insertion, and uses the sensation of De Qi to kickstart a deeper breathing pattern. Second, the explorer continues with deeper inhalation and exhalation throughout the treatment session, being careful not to breakthrough into hyperventilation.

As the session progresses, the explorer is encouraged to express movement, sound and emotion with as much spontaneity and authenticity as possible. The essential feature of DIA involves removing all potential barriers to the spontaneous movement of original energy.8

Acupuncture

Once the therapeutic context is established, the basic principles of needling are pretty straightforward. Open the Chong Mai with SP 4 (Gongsun) and PC 6 (Neiguan). Some authorities say the points have to be stimulated in a particular way, with shaking and vibrating.* Adhering to this suggestion may assist in setting an optimal intention but, ultimately, might not be required.

Why these 2 points? SP 4 represents Earth within Earth. Earth is the controlling hearth for the construction of life, and so forms an effective container for the flow of Jing into postnatal existence. SP 4 (Grandfather's Grandson) is a direct reference to the fact that it is representative of Jing. Meanwhile, PC 6 is the Luo point of the Heart and represents the access point to the Shen. Thus, these 2 points represent the potential to refocus Jing energy into the Shen to bring more awareness of innate potential to personal awareness.

Yet, that said, in practice, these 2 points are not mandatory, because other Opening and Coupled points can be used in much the same way, depending on what arises as the focal issue on any particular day—for the Dai Mai, GB 41 (Zulinqi) and TH 5 (Waiguan); for the Du Mai, SI 3 (Houxi) and BL 62 (Shenmai); and for the Ren Mai, KI 6 (Zhaohai) and LU 7 (Lieque). Or the pairs can be mixed—for example: BL 62 and KI 6 can be a very useful pair (theory would suggest this particular pair can simultaneously access Du/Ren/Yin Qiao/Yang Qiao Mai, BL and KI). LR 3 (Taichong), ST 36 (Tsusanli), and ST 42 are all acceptable choices, given that they are accessed by the Chong Mai. I will often try such points if the Qi is not adequately moving with SP 4 and PC 6, without worrying too much about theoretical considerations. Because transpersonal acupuncture is largely self-directed, the Opening points are truly just kickstarters, signaling that the DIA session is starting.

Going Up or Going Down

To access the upper Chong Mai and the Heart, KI 12 (Dahe) needs to be included, followed by suitable Kidney/Spleen/Liver points in the abdomen and chest or head.

To access the lower Chong Mai on the legs going down to the feet (one of the indications for the use of the Chong Mai is cold feet), ST 30 should be included with the addition of suitable leg and feet points, such as BL 40, ST 36, LR 3, and KI 3 (Taixi).

Although points on the Chong Mai can be found in any textbook, in reality, once the intention and context are optimal, pretty much any active (Ashi) points can be used. After that, it is simply a matter of going with the flow, which means asking the explorer to breathe steadily, move freely and express emotions as they occur. All the time, the dyad moves toward whatever symptom might be arising in the moment, searching and volunteering points as they arise.

Case Studies

Case 1

A 50-year-old woman had fallen off her bicycle some 20 years previously, fracturing her jaw. The mechanics of her fall involved flying over the handlebars while still holding onto them. She hit the pavement chin first and broke her mandible, which required surgical repair. Subsequently, she remained in chronic pain.

I worked with her for some time until she had a clear Golden Gate experience. Subsequently, the transition occurred with increasing frequency. She would arrive for her appointment in pain and frustration, and emerge half an hour or so later in a blissful haze, for all the world wondering what she had been complaining about earlier. After a while, I wondered what to do next. She seemed adept at transitioning, but had difficulty maintaining the emergent state.

As I got to know her, it became apparent how much her ego was invested in the Wood-related theme of searching for reasons to be hostile. In the meantime, her emergent post-Gate personality was much more about warmth and compassion, Fire-related themes.

Perhaps her natural Fire had been all but extinguished by the accident. And this loss of Spirit became a theme in other areas. To be sure, she had difficulties in the Heart Palaces of relationship and work, and indeed had been through a difficult relationship breakup that left her feeling bitter and abandoned. It was all very well to open the Heart temporarily, but how to sustain the change was another matter.

I decided to switch to the Chong Mai, using points such as SP 4, PC 6, LR 14 (Qimen), and CV 17 (Danzhong). This switch in focus produced more lasting results, and, in time, she relinquished her rage, found a new fulfilling relationship and, as of this writing, is more settled and pain-free.

Case 2

A 60-year-old woman suffered from debilitating headaches for many years. The headaches were often one-sided, but could occur on either side, and had previously been diagnosed as migraines. She had tried acupuncture with other practitioners without success, and overrelied on codeine-based medications.

Superficially, the symptoms seemed to form a straightforward Gall Bladder pattern, and so, initial acupuncture focused on the common headache strategy of releasing the excess Yang in the head, with points such as GV 16, GV 20, and EX HN-5 (Taiyang). However, this strategy produced only partial success, with a very temporary diminishment of symptoms.

I switched to a primary channel approach. Palpation revealed many trigger points in the Front zone—up the legs, abdomen (where there was a cesarean-section scar), chest, neck, and face—indicating significant Stagnation in the Yang Ming. This seemed to fit with her likely Yang-Ming Earth Constitutional type. However, she also had suboccipital triggers and low-back pain (Tai Yang), and also had shoulder tension and hip pain (Shao Yang). This all presented a confusing picture.

I tested the channel system sequentially— using points on the Tai Yang–Shao Yin, such as BL 10 (Tianzhu), BL 60 (Kunlun), and KI 3; the Shao Yang–Jue Yin, such as LR 3, and GB 20 (Fengchi); and the Yang Ming–Tai Yin, such as SP 3 (Taibai), ST 36, and ST 8 (Touwei)—incorporating the points into both linear and various energetic equilibrations, as described by Helms.5 This approach led to more encouraging results, with periodic myoclonic activity in the legs associated with temporary headache release. After these releases, she would feel deeply relaxed, indicating what I understood later to be a Golden Gate transition.

The next step was to try to stabilize this post-transition state. Further inquiry revealed that she had undergone 2 cesarean sections and a subsequent hysterectomy. She also had lumbar spondylosis. Palpation revealed a Hot Above–Cold Below (the diaphragm) energetic configuration, indicating a Chong Mai split involving the Dai Mai.

It was this observation that triggered the move to using the Chong Mai–Dai Mai. We had been working together long enough that a non-dual exploration was possible. Acupuncture then involved SP 4 with Moxa, PC 6, SP 6 (Sanyinqiao), ST 30, and the Dai Mai (GB 41 and TH 5), LR 13 (Zhangmen), GB 25 (Jingmen), and GB 26 (Daimai). Not all points were used during each session.

This strategy produced excellent results, with shaking down the legs into the feet, a faster response time, and more-lasting results. Gradually, she became more familiar with the post-Gate state, and was able to stabilize the state better with regular meditation. This patient still comes monthly for acupuncture treatments and no longer takes analgesic medication.

Case 3

A 72-year-old woman presented with severe abdominal cramping, which had been steadily worsening over the preceding 5-years. The pain was sufficiently severe that she would often end up in the emergency room, waiting sometimes for hours hoping to obtain some relief. Ultrasounds (USs), computed tomography scans, and endoscopy followed, revealing gallstones and diverticulosis, both likely incidental, given that antibiotics and a subsequent cholecystectomy made no difference. After multiple investigations, she was told she had irritable bowel syndrome and that she would need to learn to live with her symptoms.

Acupuncture treatments were initiated on the theory of Liver invading Spleen, using points such as LR 3, ST 25 (Tianshu), ST 36, ST 37 (Shangjuxu), and herbal preparations such as Xiao Yao San (Free and Easy Powder). Although the approach helped temporarily, it did not give lasting results.

She was more than willing to try a deeper exploration. Her ego had taken a severe battering anyway and so traversing the Gate was not seen as a threat. DIA techniques were initiated, using Chong Mai/EM Opening and Coupled points, plus abdominal Ashi points as they arose. One consistent useful point was LR 10 (Tsuwuli), needling deeply to access the psoas muscle. Both Front and Back points were used.

Immediately after needle insertion she would begin side-to-side pelvic movement, with myoclonic shaking in the legs, shoulders, and arms. Post treatment, she entered a calm pain-free state that lasted for several hours. Treatments were performed daily for 2 weeks, then 3 times per week for 2 months, and then weekly. Her symptoms gradually subsided.

Case 4

A 90-year-old woman had phantom-limb pain following a right-leg above-the-knee amputation for vascular disease several years previously. She had tried a number of things, including massage, physiotherapy, US, and Botulinum toxin, but acupuncture worked better than everything else.

After several months of trying various approaches, including principle meridian, the method of Richard Teh-Fu Tan, OMD, LAc,9 and local Ashi points, I switched to the Chong Mai, using PC 6 and ST 30 bilaterally, and KI 10 (Yingu) and BL-40 on the unamputated leg, together with gentle stump massage. With this approach, her thigh would vibrate visibly and she was able to feel Qi moving down the absent leg into KI 1 (Yongquan), while simultaneously the phantom pain decreased significantly. The relief lasted up to 2 weeks as opposed to the few days she was obtaining before.

Discussion

The idea that it might be possible to take a complex EM framework and reduce it to a relative minimalism might, at the outset, sound like an excuse for poor acupuncture practice. However, complexity can sometimes be its own downfall, and healing is often a simple matter when it happens. For example, the phenomenon of spontaneous remission of cancer, in a nonacupuncture context, has been well-documented.10 In most cases, the remissions are not actually spontaneous at all, but rather a reflection of fundamental changes within the patients, in which they have achieved an enlarged and more integrated sense of self.

Familiarity with meditation/relaxation techniques can be helpful to grasp simplicity. Long term meditators might have experienced the body warming up at a certain point of deep relaxation. In conventional terms, this could be understood as the result of relaxation of the blood vessels. In terms of CM theory, this experience points to bringing the Shen (Yang) and Jing (Yin) together, uniting Fire and Water via the Chong Mai. The idea is to simply relax everything, to let go, and let the Heat of the Heart and Lungs sink down into the lower abdomen. This unites Yin and Yang, Heaven and Earth, Shen and Jing. What could be easier—doing nothing, while achieving everything? Many books have been written about this improbable notion of effortless mastery, but the idea goes right back to the philosophical foundations of CM. As Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj put it: “Give up all and you gain all.”11

Conclusions

Chong Mai treatments are best reserved for patients who have had a significant acupuncture experience transcending the Golden Gate. This typically goes hand in hand with a philosophical shift that moves them beyond the standard hierarchical therapeutic relationship. It is these patients who are willing to accept responsibility for their symptoms and who have given up the need to eradicate them who truly have strong candidacies for a unified Chong Mai approach.

Although finding the right moment with any particular patient to initiate a treatment based on a simplified Chong Mai needling strategy is difficult to define, practitioners may well be familiar with the non-dual therapeutic relationship that is the bedrock of this method because it tends to develop naturally. There is no longer a sense of being a practitioner choosing points on the basis of theory. Instead, it is replaced by an awareness that the acupuncture treatment is becoming more of an experiential exploration.

That said, there can be no doubt of the results, which improve exponentially as the context shifts.

Acknowledgments

Graphics were designed by Dr. Greenwood's son, Richard Greenwood, BFA, MA (website: www.richardgreenwood.ca).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Yuen J. The Eight Extraordinary Vessels (Qi Jing Bai Mai). Class notes, Winter/Spring, 2004, transcribed by Nicholas V. Isabella. Online document at: www.point-to-point-acupuncture.com/files/The_8-Extra_Vessels.pdf Accessed November 1, 2017.

References

- 1.Jarrett L. Constitutional Type and the Internal tradition of Chinese Medicine—part I: The ontogeny of life. Am J Acupunct. 1993;21(1):19–32 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jarrett L. Constitutional type. In: Nourishing Destiny: The Inner Tradition of Chinese Medicine. Stockbridge, MA: Spirit Path Press; 1998:137–167 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenwood MT. Shifting a paradigm with acupuncture: 5-Phases and the Mysterious Path. J Aust Med Acupunct Coll. 2006;22(1):5–16 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twicken D. The Chong Channel. In: The Eight Extraordinary Channels, Qi Jing Ba Mai: A Handbook for Clinical Practice and Nei Dan Meditation. London: Singing Dragon/Kingsley; 2013:45–62 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics—a Clinical Approach for Physicians. Berkeley, CA: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood MT. Acupuncture and the chakras. Med Acupunct. 2006;17(3):27–32 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maxwell D. Tangible medicine: An interview with Andrew Nugent-Head. J Chin Med. 2012;99:27–34 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenwood MT. The Unbroken Field: The Power of Intention in Healing. Victoria, British Columbia: Paradox Publishing; 2004:219–220 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan RT-F. Dr. Tan's Strategy of Twelve Magical Points. San Diego: Richard Tan; CA; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner KA. Radical Remission: Surviving Cancer Against All Odds. New York: HarperCollins; 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nisargadatta Maharaj S. Give up all and you gain all. In: Friedman M, transl. I Am That: Talks with Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. Mumbai, India: Chetana Private Ltd.; 1999:209–213 [Google Scholar]